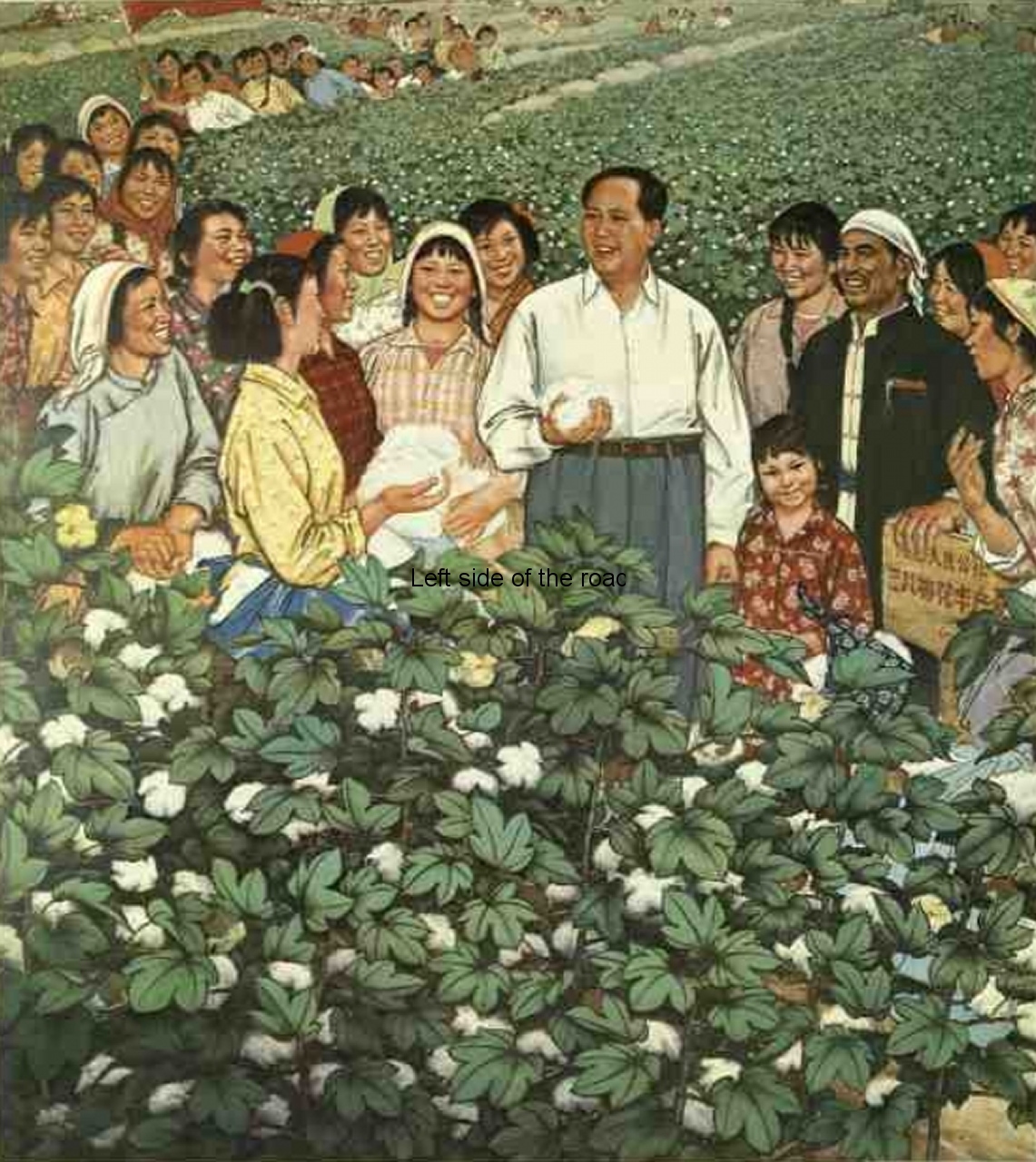

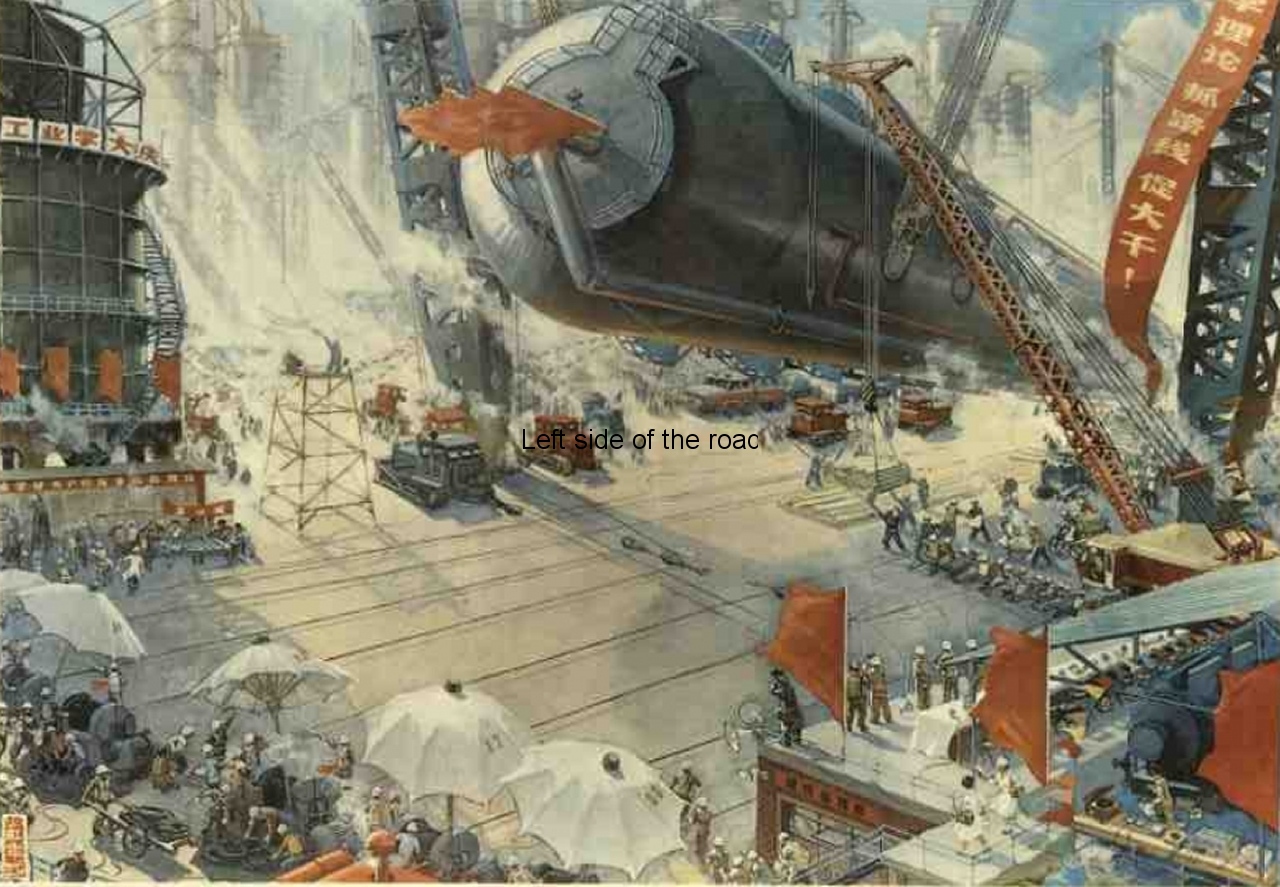

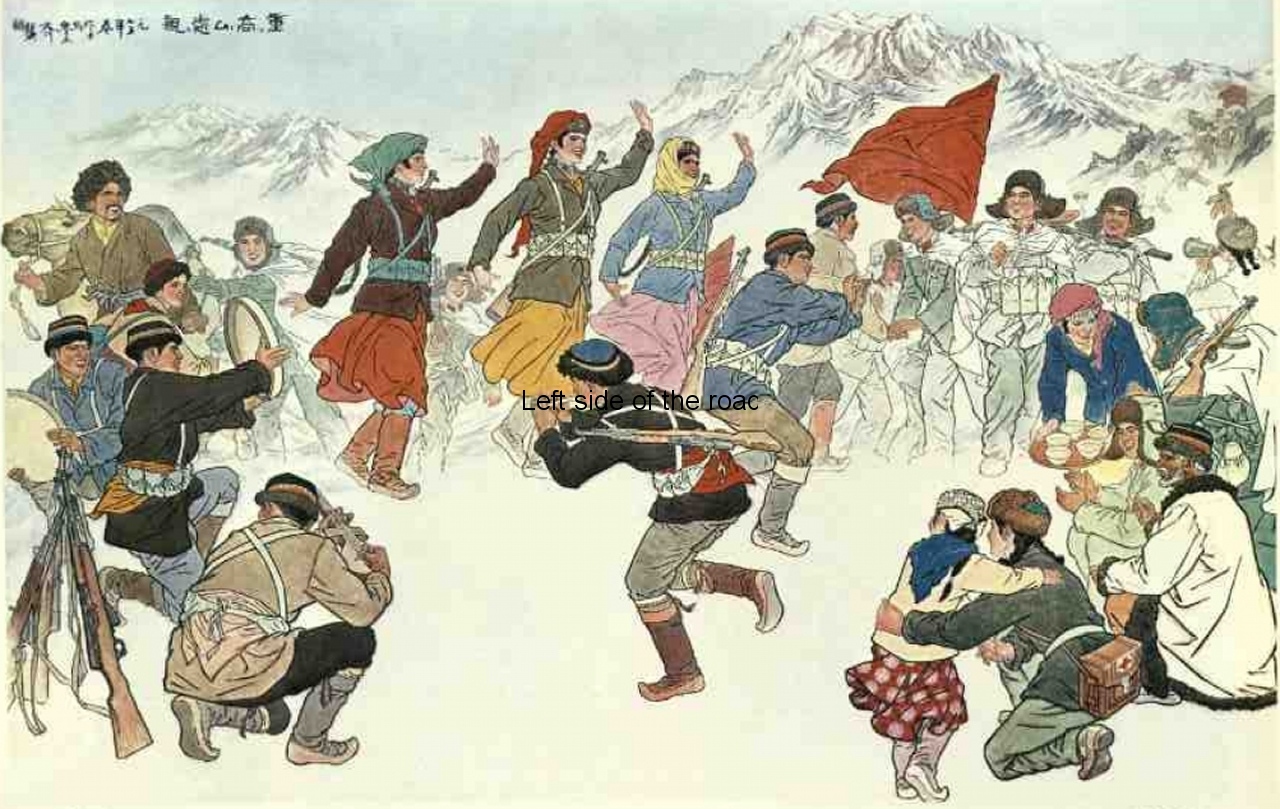

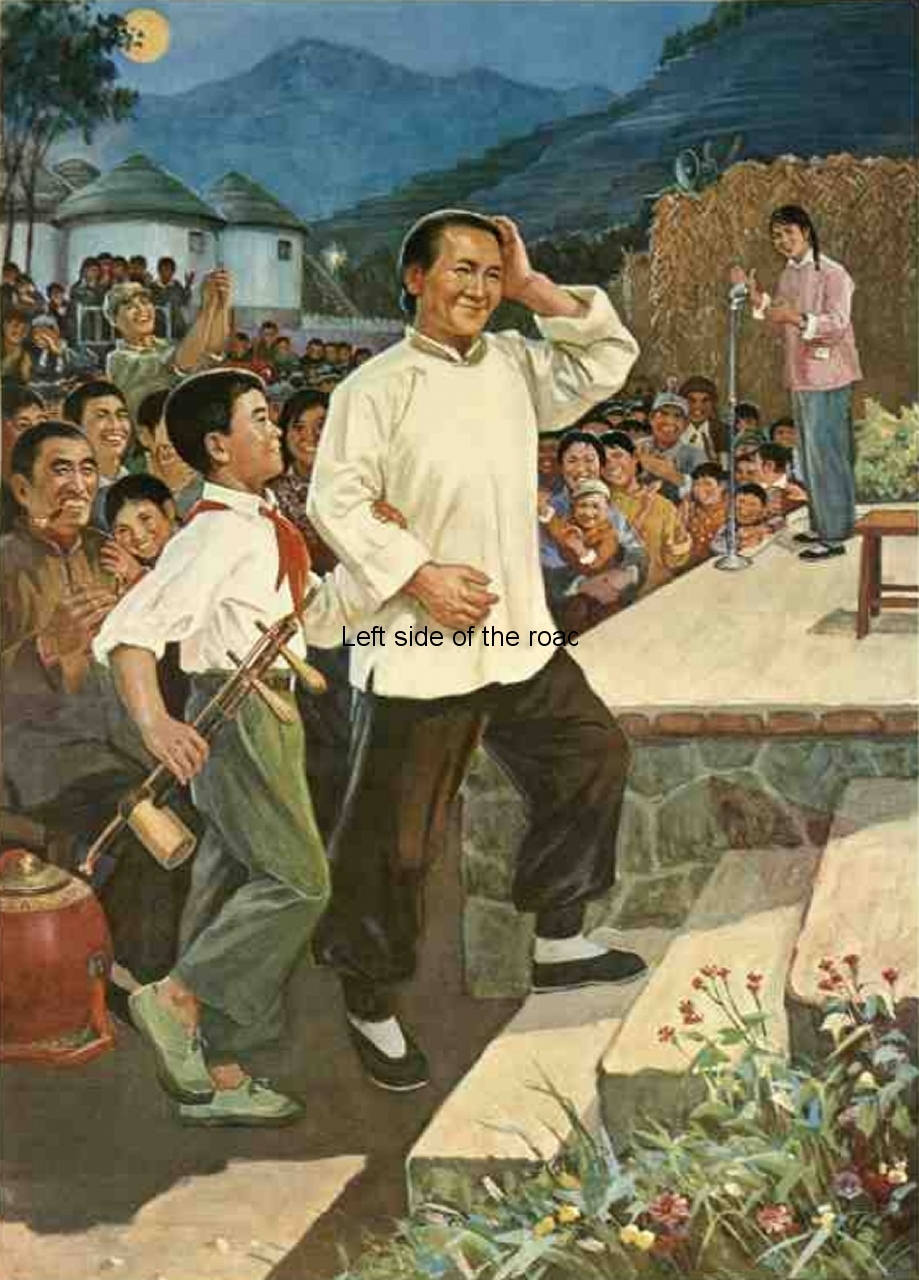

The workers are the most imaginative

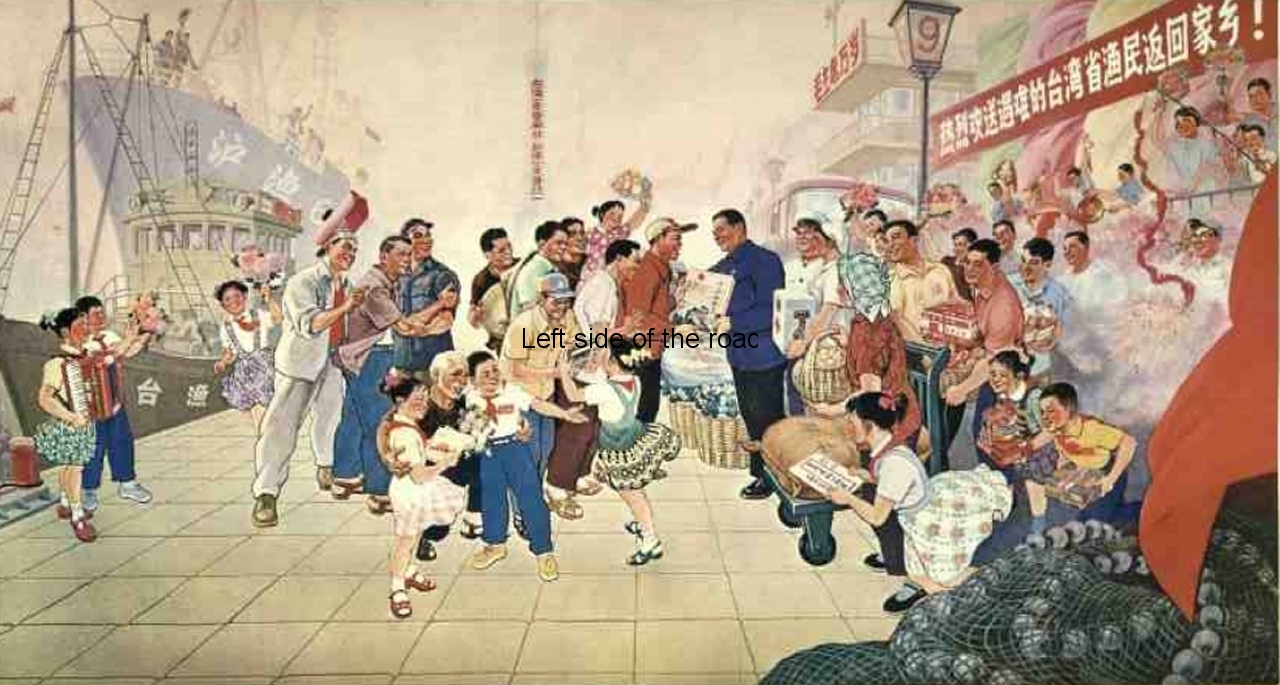

More on China …..

Chinese Literature Magazine 1951-1981

‘In the world today all culture, all literature and art belong to definite classes and are geared to definite political lines. There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake, art that stands above classes, art that is detached from or independent of politics. Proletarian literature and art are part of the whole proletarian revolutionary cause; they are, as Lenin said, cogs and wheels in the whole revolutionary machine.’

From: “Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art” (May 1942), Mao Tse-tung Selected Works, Vol. III, p. 86.

Even whilst prosecuting, organising and developing military tactics in the war against the Japanese Fascist invaders Mao realised that literature and art were not only important to success in that campaign but he was also laying the foundations for the construction of Socialism once victory had been won.

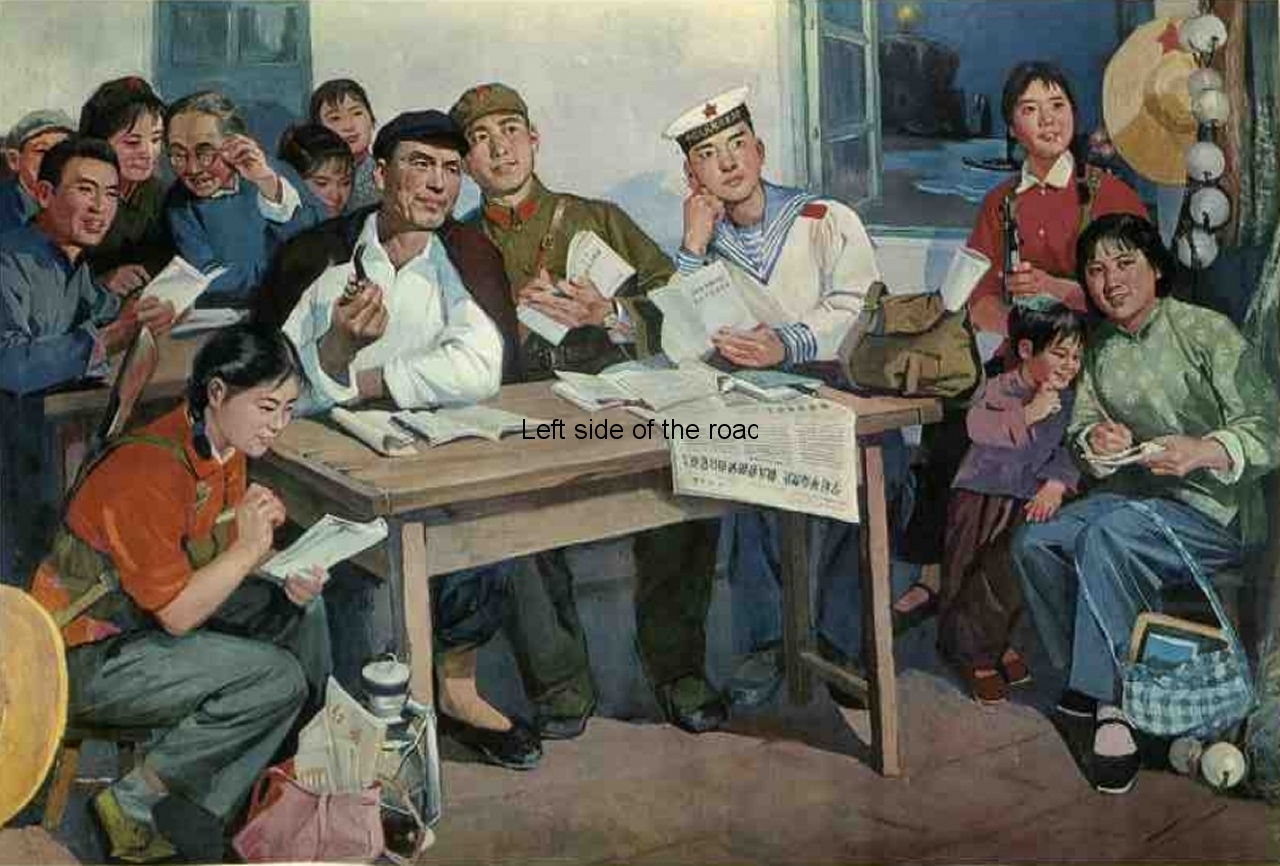

In this he followed in the footsteps of both Lenin and Stalin, in the Soviet Union, who had both realised that Socialism cannot be achieved solely by taking political control as well as the ownership of the land and industry – what was more important was convincing and changing the thinking of those who had been brought up in ignorance, subservience and a lack of confidence in what they could attain, if only they tried.

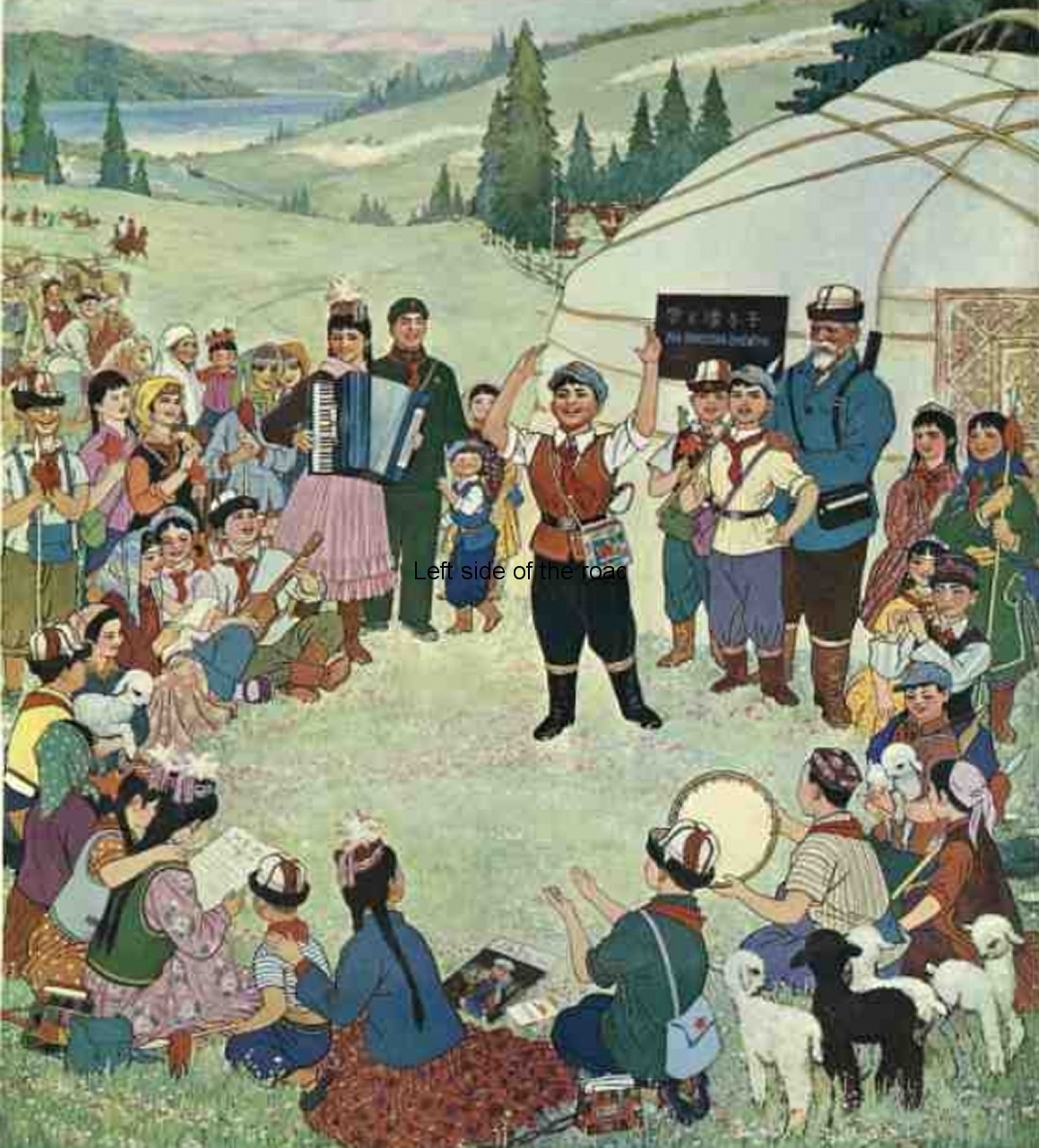

Education, literature, art (in all its forms) and science – which could only be achieved through massive and extensive literacy and numeracy campaigns – was integral to this new, workers and peasants inspired ‘Enlightenment’.

In no country in the world – even in Britain where the first industrial revolution really started to change society – did the ruling capitalist class make a concerted effort to ‘educate’ the oppressed workers and peasants until there had been a movement from those exploited workers to educate themselves.

Religion, in all its insidious forms throughout the world, was the only education the oppressed needed – to maintain their oppression. In virtually all those societies the control of knowledge was in the hands of the ruling ‘elite’ and their theocratic hangers-on.

Ignorance was perpetuated by; the fear of eternal damnation in the afterlife – whether a hell or as coming back as something even more insignificant than the present; imagery, be it paintings or statues in European Christian churches, fed fear and subservience; crass, sycophantic homilies from the likes of Confucianism in Asia – and its tireless variants where kowtowing is the norm; or the situation of tribal elders and ‘caciques’ maintaining their control in Africa and Latin America the aim was ‘not to rock the boat’.

But the aim of Communists is not to rock but to sink the boat.

Through knowledge, through culture, through a realisation of their power workers and peasants throughout the world can ‘turn the world upside-down’.

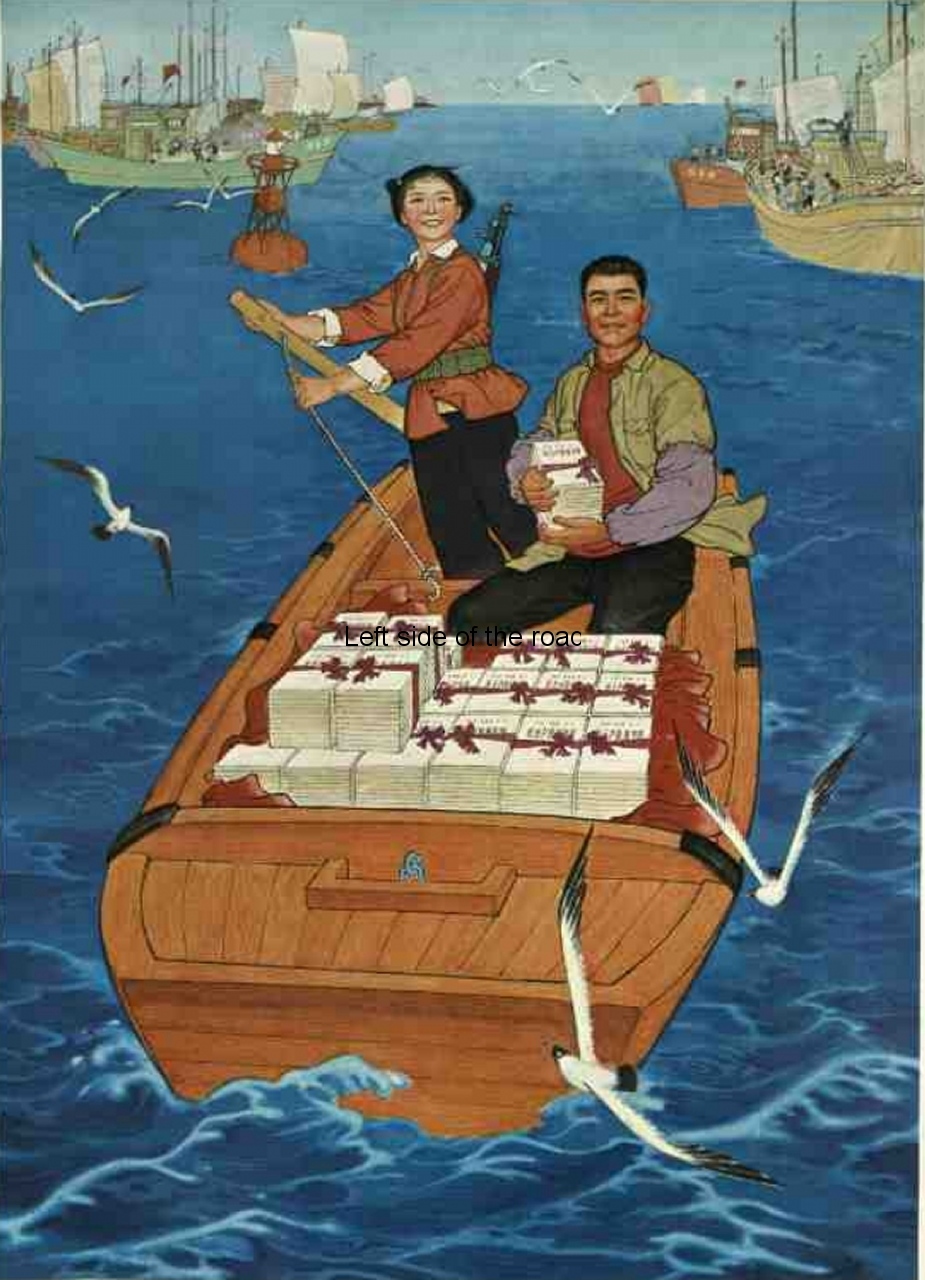

After Mao made the short declaration of the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in Tienanmen Square on 1st October 1949 the new state set about putting the theory into practice.

Within a couple of years they were producing material in English to show the rest of the world what they were doing, giving the lead in the production of a new proletarian culture.

Unfortunately we do not have access (as of yet) of all these magazines but a significant number are presented to the rational and thinking reader.

If anyone can help in filling in the gaps that effort will be very much appreciated.

Welcome to Chinese Literature.

1951:

(Not yet available)

1952:

(Not yet available)

1953:

Different types of birds

- 1 – Spring, 324 pages. Contents include:

On the ideological remoulding of writers and artists

Remould our thoughts to serve the masses

Sun over the Sangkan River (Stalin Prize for Literature winner 1951) – complete novel

- 2 – Summer, 158 pages, Contents include:

‘The White Haired Girl’ – Chinese Opera – which was to become one of the ‘model plays’ of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

Chu Yuan: Great Patriotic Poet – a poet from the Warring States period of Chinese history, in the 4th century BCE

- 3 – Autumn (Not yet available)

- 4 – Winter (Not yet available)

1954:

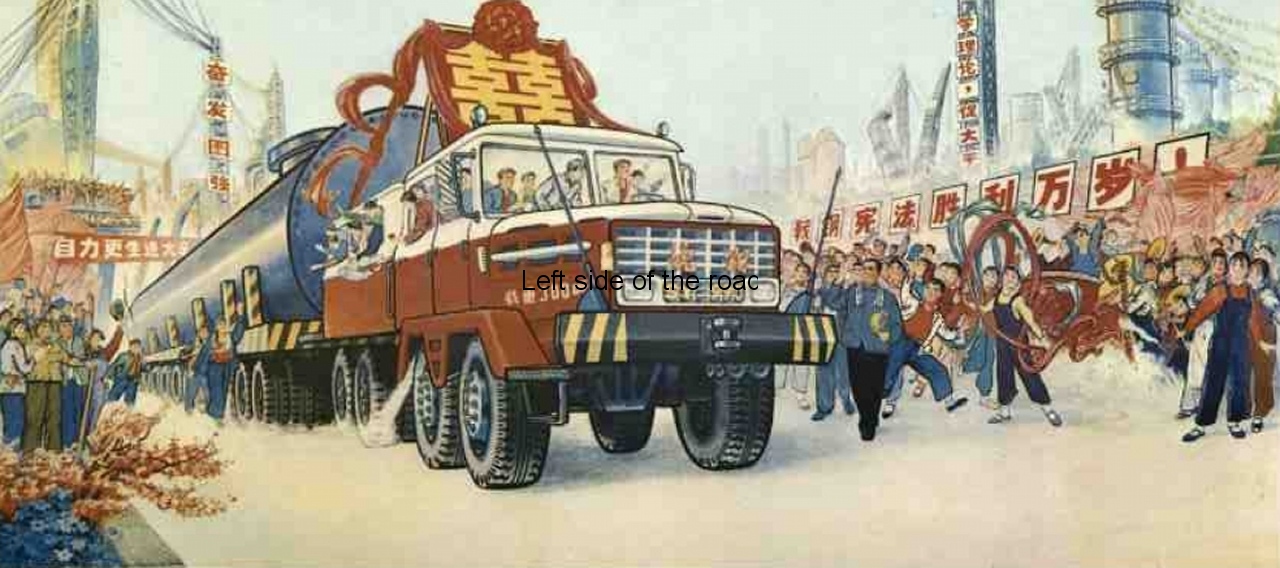

Celebrating the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China

- 1 – Spring, 182 pages. Contents include:

Two stories – Lu Hsun

Chinese folk songs – Ho Chi-fang

New realities and new tasks – Mao Tun

- 2 – Summer, 246 pages. Contents include:

‘Wall of Bronze’ – part of a novel about the Chinese People’s War of Liberation

Short stories from the Tang period (618-907)

Comrade Huang Wen-yuan – the story of a Chinese volunteer in the Korean War

- 3 – Autumn, 184 pages. Contents include:

Stories for children

Life and creative writing – Ting Ling

Mrs Shih Ching – Ai Wu

- 4 – Winter, 218 pages. Contents include:

The lives of the scholars – Wu Ching-tzu

The realism of Wu Ching-tzu

‘The Palace of eternal youth’ and its author – Hung Shen

1955:

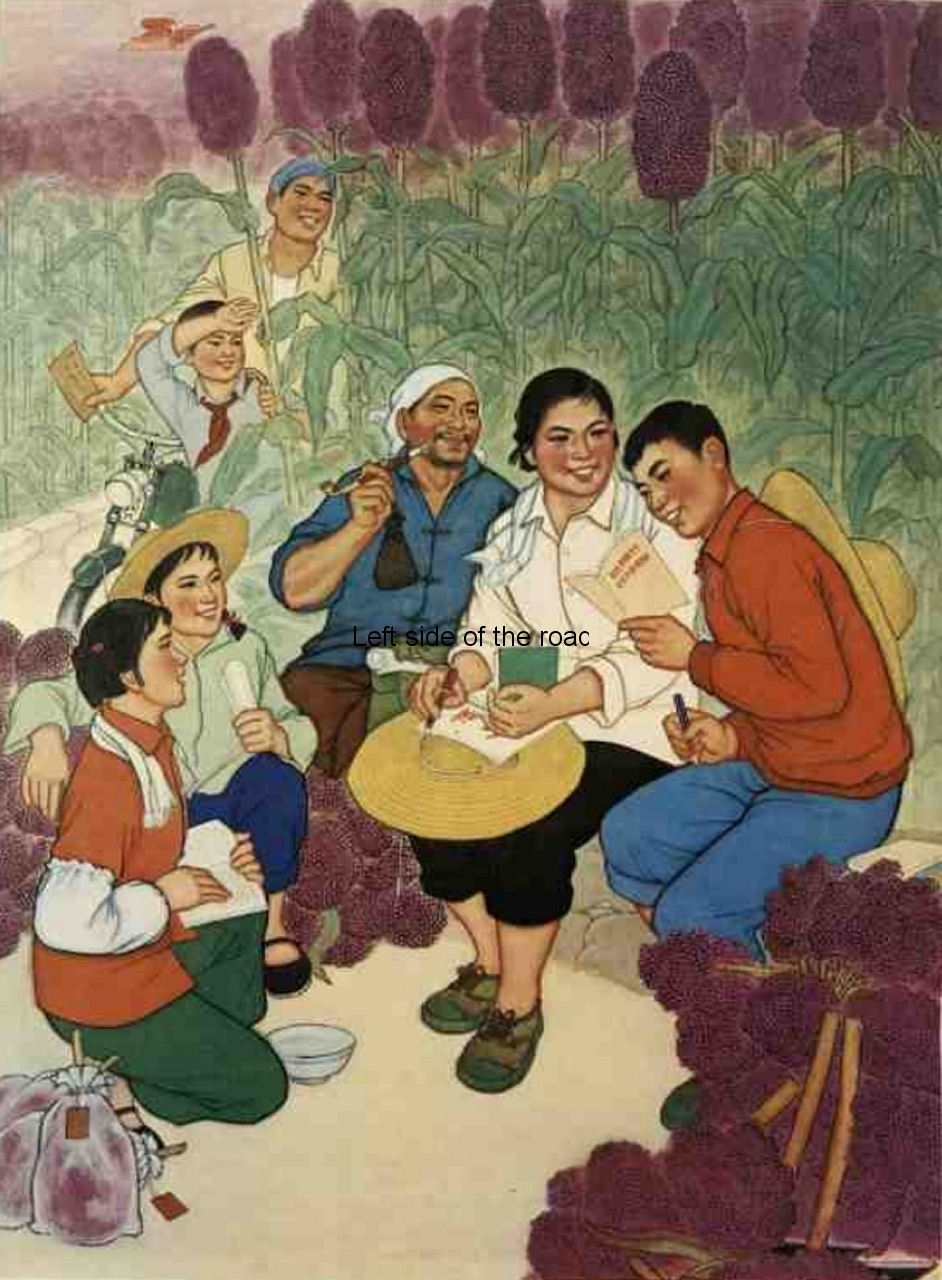

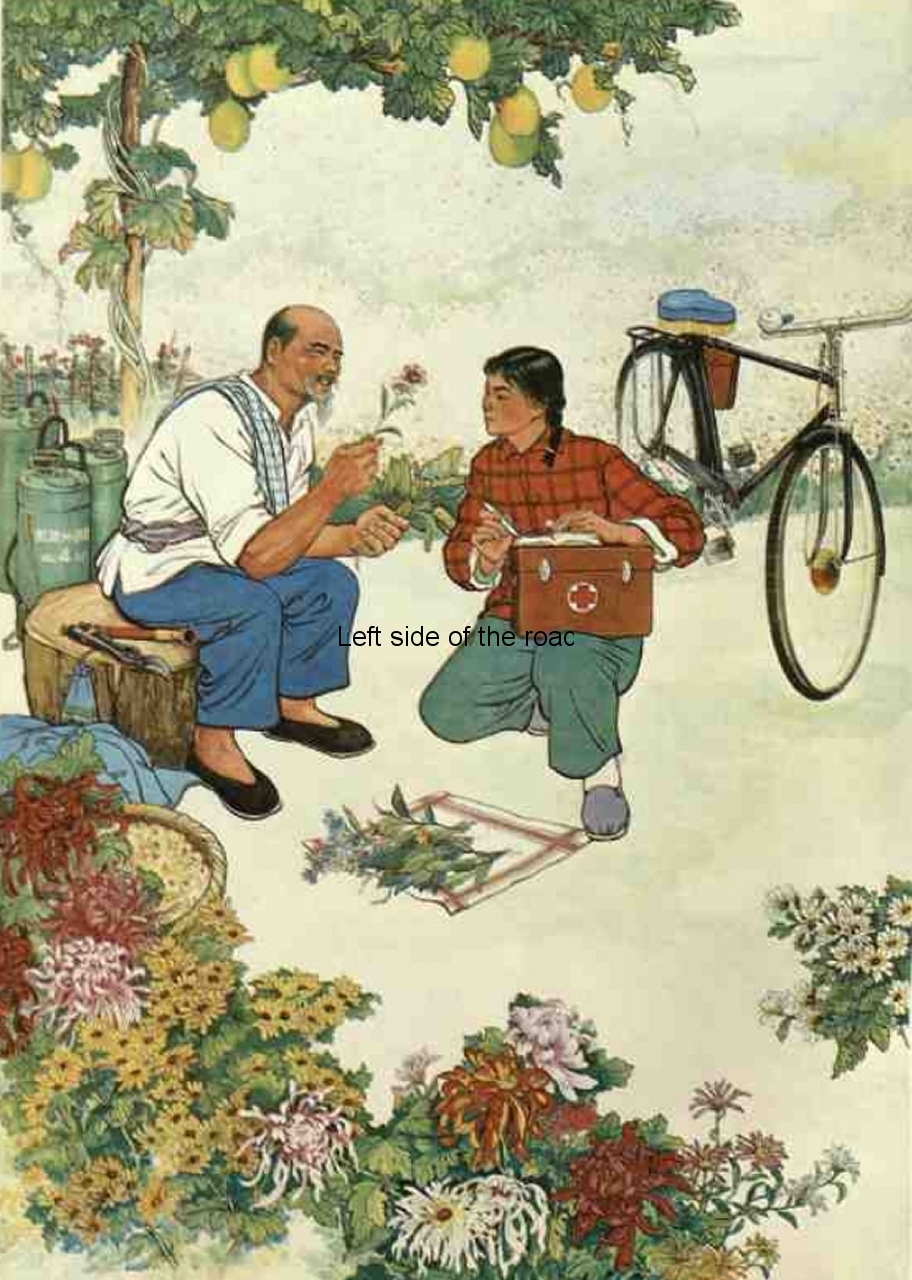

Looking at chrysanthemums

- 1 – Spring, 216 pages. Contents include:

Short stories from new Chinese writers

Tales from the Sung and Yuan Dynasties

Cultural events – news about recent developments in the cultural sphere

- 2 – Summer, 194 pages. Contents include:

Tu Fu (a poet of the Tang Dynasty in the 8th century) – Lover of his people

Poems of Tu Fu

Cultural Events – developments in the cultural field

- 3 – Autumn, 186 pages. Contents include:

Ashma, a Shani ballad

Early vernacular tales – Fan Ning

Stories from the Ming Dynasty

- 4 – Winter, 186 pages. Contents include:

The Test, a play in five acts – Hsia Yen

Sanliwan village, a new novel

The legend of the rose – Wei Chi-lin

1956:

State cattle farm

- 1 – Spring (Not yet available)

- 2 – Summer (Not yet available)

- 3 – Autumn, 231 pages. Contents include:

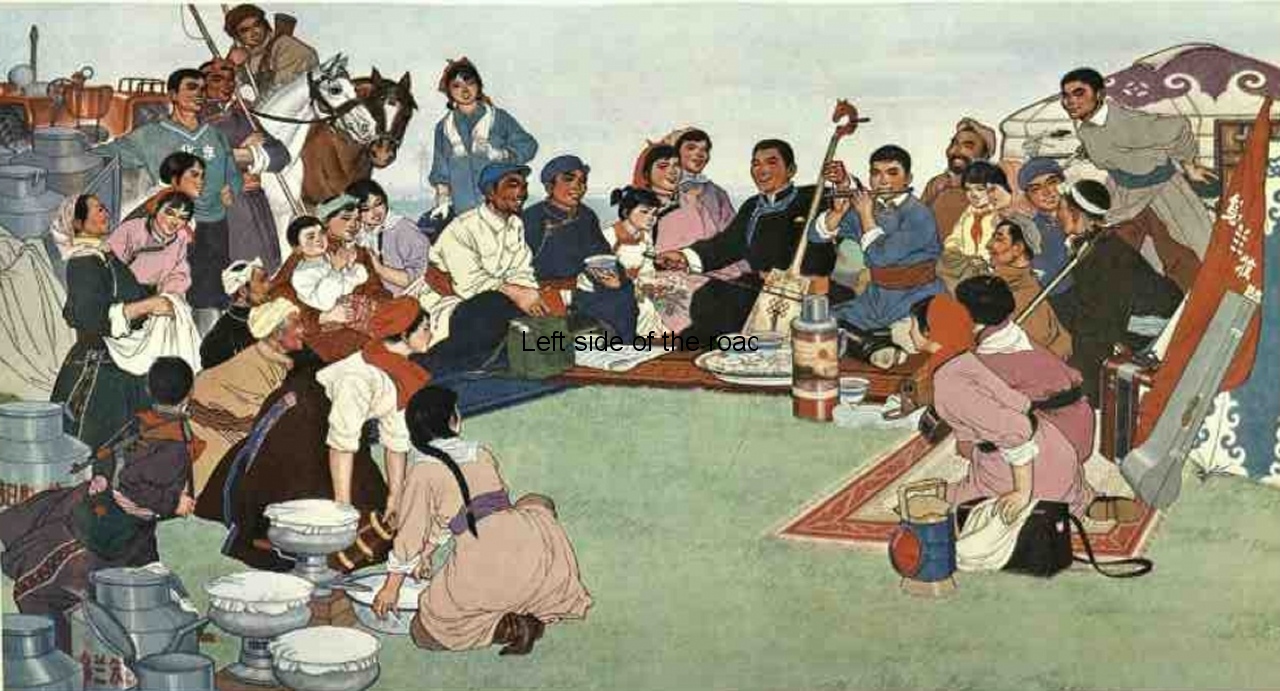

Poems and folk tales from the Uighur national minority

A Thousand Miles of Lovely Land – a novel written by Yang Shuo, a Chinese Volunteer in the Korean Fatherland Liberation War

Reminiscences of Lu Hsun

- 4 – Winter, 268 pages. Contents include:

Articles on; ‘Building a Socialist literature’ and ‘The key problems in literature and art’

Four short stories by Lu Hsun

Fifteen Strings of Cash – the libretto of a Kunchu Opera

A series of wood engravings commemorating the 20th anniversary of the death of Lu Hsun

Index for 1956 issues.

1957:

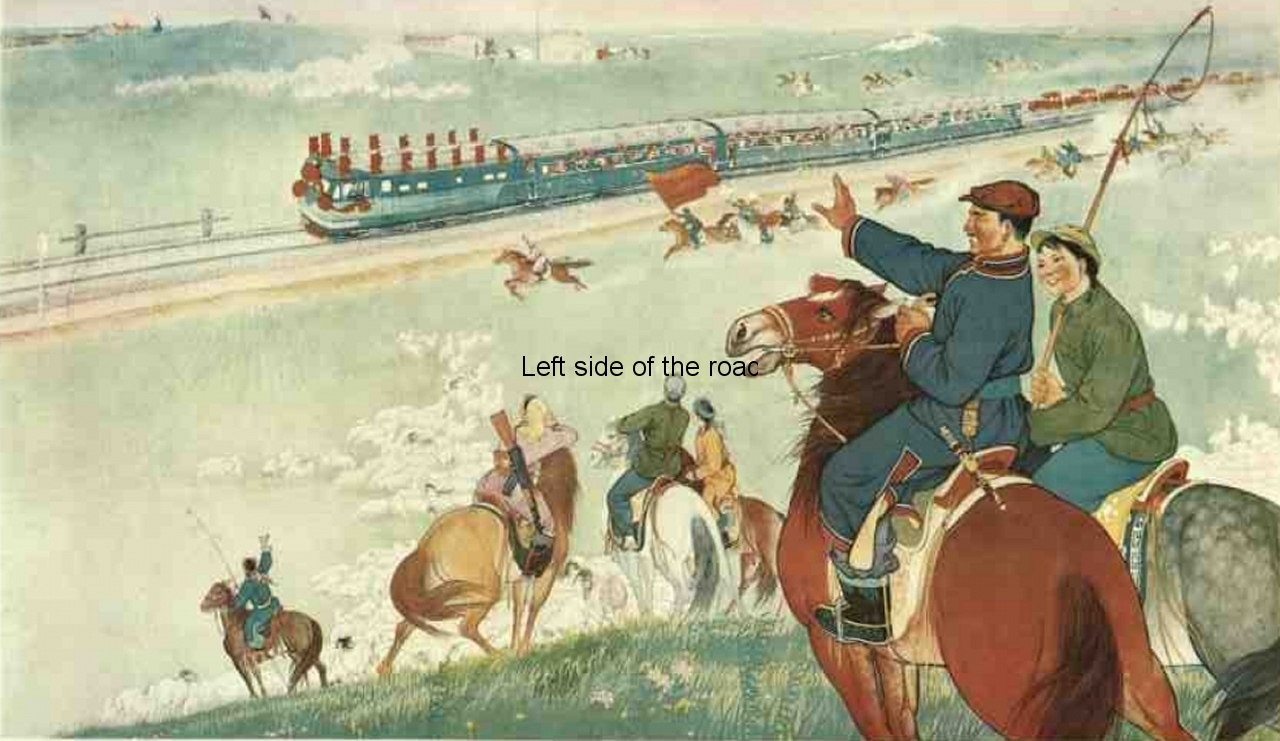

Through co-operation the electric light is fixed

- 1 – Spring, 229 pages. Contents include:

An article on the important role of art and literature in the building of Socialism

Kuan Han-Ching – Outstanding Dramatist of the Yuan Dynasty

Stories about Children

- 2 – Summer, 250 pages. Contents include:

Three One-Act Plays – written by worker/peasants in Socialist China

China’s classical and modern literature – comparing and contrasting the role of literature throughout China’s history

Mongolian folk tales

- 3 – Autumn, 236 pages. Contents include;

Two short stories by Yu Ta-fu

Ancient Chinese sculpture

Controversy over art and literature

- 4 – Winter, 212 pages. Contents include;

Fifteen years since the Yenan ‘Talks’

Reminiscences of the Red Army Veterans

Five Tibetan fables

Chinese ghost and fairy stories of the 3rd to the 6th century – Hsu Chen-Ngo

1958:

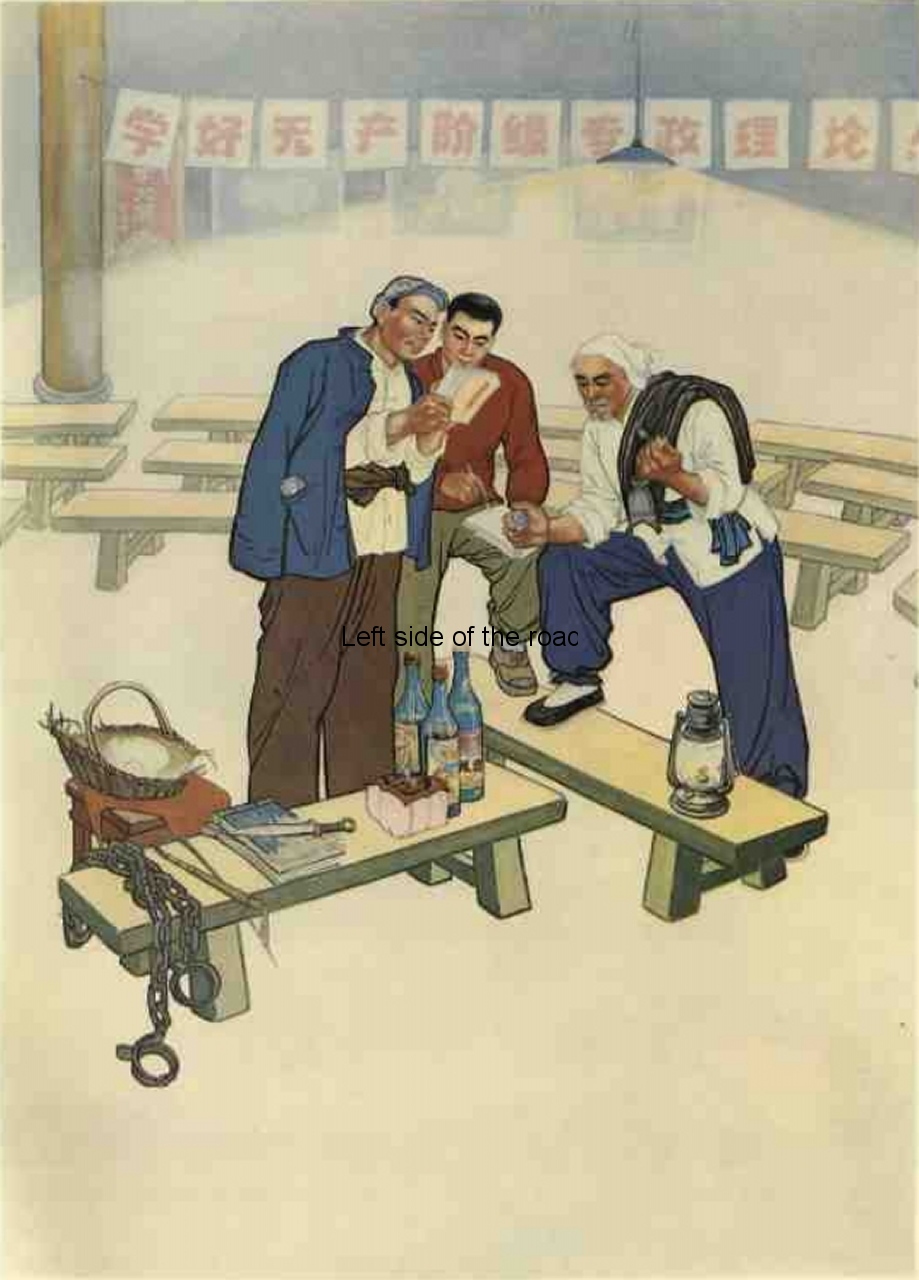

Please give it back to the owner

The October Revolution and the task of building a Socialist culture – Chou Yang

A journey into strange lands – Li Ju-chen

Poems – Emi Siao

Revisionist ideas in literature – Yao Wen-yuan

Next-time port (a children’s story) – Yen Wen-ching

Writers forum: Notes on life – Lei Chia

- 3 – May-June, 178 pages. Contents include;

Eighteen poem by Mao Tse-tung

A great debate on the literary front – Chou Yan

Kuan Han-ching, a great thirteenth century dramatist – Cheng Chen-to

The Peacock Maiden, a folk tale

On the Tibetan Highland (portion of a novel) – Hsu Huai-chung

Indian literature in China – Chi Hsien-lin

The historical development of Chinese fiction (Part 1) – Lu Hsun

Notes on literature and art – a series of three articles looking at the past and the present

The Self-Destruction of Howard Fast – a critical appraisal of the North American writer

-

- Supplement: ‘Oppose U.S.-British interference in the internal affairs of the Arab Countries’, against imperialist military intervention in Lebanon, Iraq, and other countries, 20 pages.

- 6 – November-December, 194 pages. Contents include:

The historical development of Chinese fiction (Part 2) – Lu Hsun

Episodes from the Korean War

A collection of 43 Folk Songs

-

- Supplement: ‘Statement of Chou En-lai … on the situation in the Taiwan Straits area’, and two related documents, 8 pages.

1959:

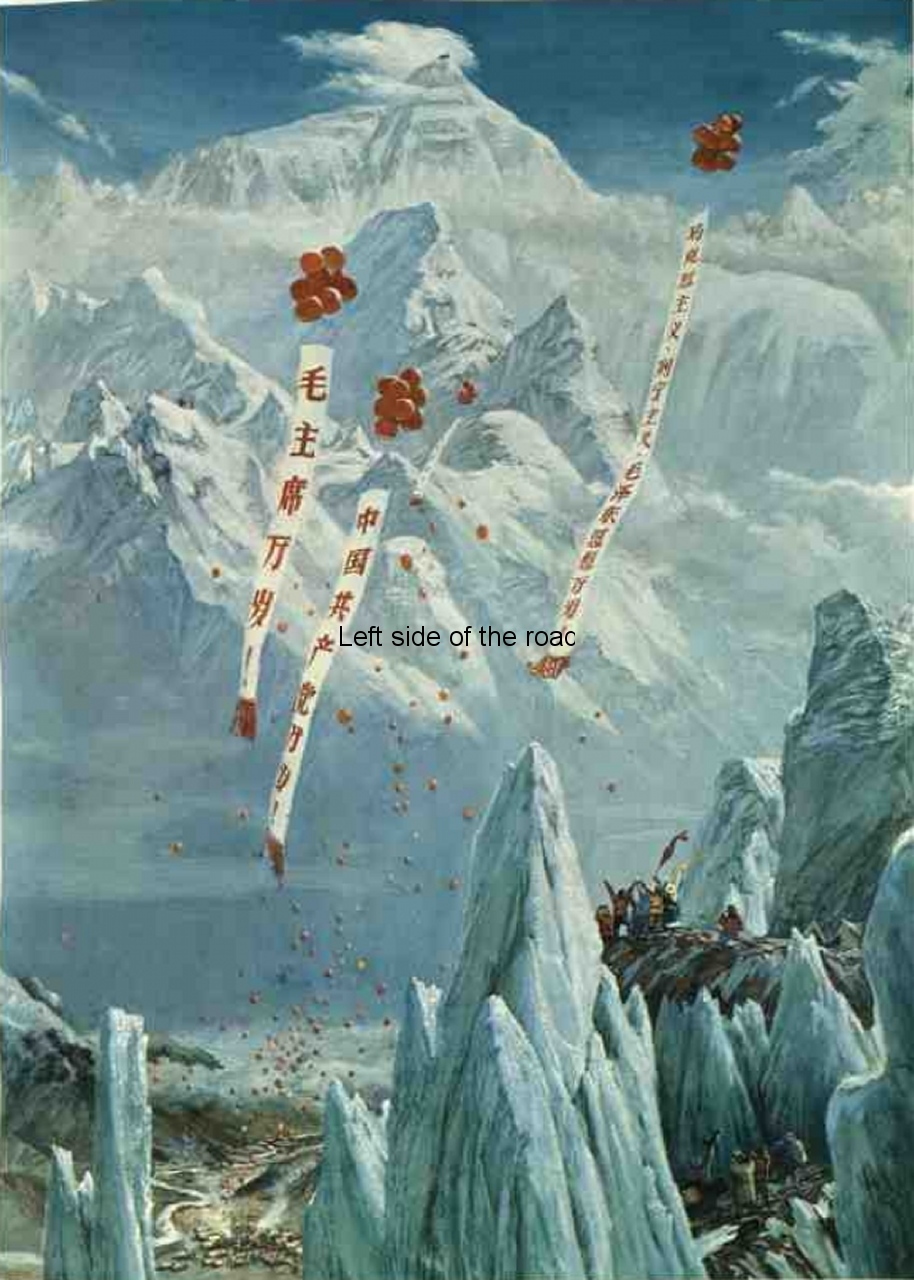

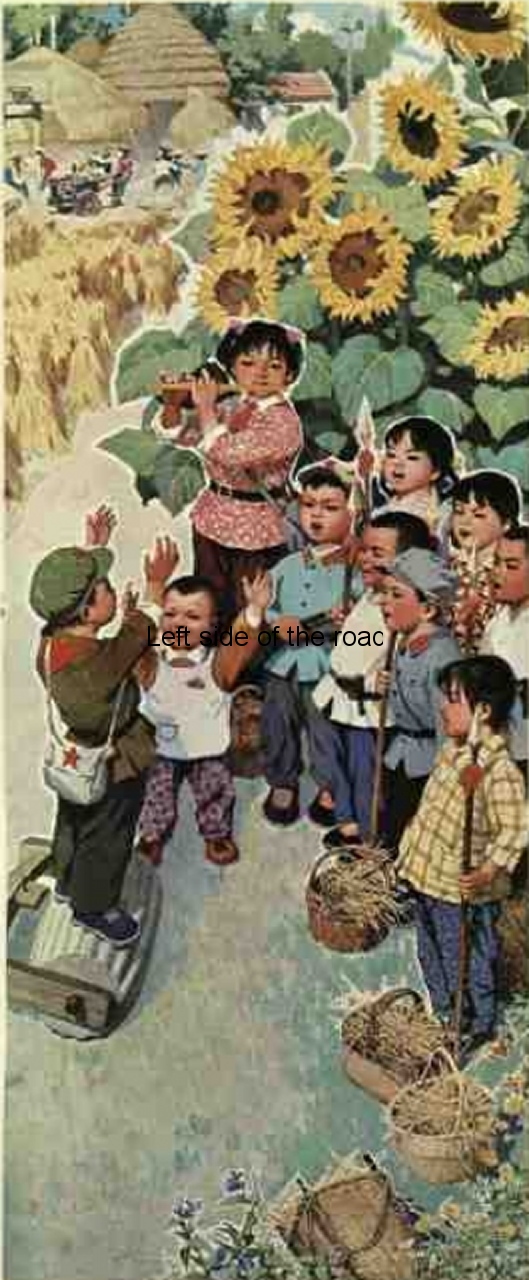

Onward, towards and even higher goal

- 1 – January, 258 pages. Contents include:

Chinese literature in 1958 – Shao Chuan-lin

The Tashkent spirit: Appeal of the Asian and African Writers Conference to World Writers

An ordinary labourer – Wang Yuan-chien

- 2 – February, 232 pages. Contents include:

Travel notes: a visit to the Old Soviet Areas – Wu Wen-tao

Keep the Red Flag flying (second instalment of a novel) – Liang Pin

Notes on literature and art: New traditions in Chinese prose – Wu Hsiao-ju

- 3 – March, 182 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: Peking Stage in 1958 – Yu Wen

Chinese picture story books – Chiang Wei-pu

Folk tales: The envoy of the Prince of Tibet

- 4 – April, 158 pages. Contents include:

Yueh-fu song: The bride of Chiao Chung-ching – Anonymous

Notes on literature and art: Dough figures – Yang Yu

Reminiscences: Forest of the rustling leaves – Huang Hsin-ting

- 5 – May, 182 pages. Contents include:

The May the Fourth New Cultural Movement – Mao Tse-tung

Essays – Lu Hsun

Writing for a great cause – Chu Chiu-pai

- 6 – June, 163 pages. Contents include:

The SS International Friendship – Lu Chun-chao

Profile: Chang Tien-yi and his young readers – Yuan Ying

Writings of the last generation: On the bridge – Wang Lu-yen

- 7 – July, 184 pages. Contents include:

Bridges galore (a Szechuan opera)

Travel notes: The inarticulate traveller – Chen Pai-chen

Notes on literature and art: Szechuan Opera – Wang Chao-wen

- 8 – August, 166 pages. Contents include:

The Cloud Maiden – Yang Mei-ching

Praying for rain (a Tantzu story) – Yang Pin-kuei

Stories: The shrewd vegetable vendor – Wang Wen-shih

Lu Hsun on Literature and Art

Sunflowers turned into big mushrooms – Kao Hsiang-chen

Fourth sister – Hai Mo

The worker’s village (a poem) – Man Jui

Notes on literature and art: My new opera – Mei Lan-fang

Performances from abroad – Yang Yu

- 11 – November, 164 pages. Contents include:

The glow of youth (an essay) – Liu Pai-yu

Notes on literature and art: The modern Chinese theatre and the dramatic tradition – Ouyang Yu-chien

Stories: A bridge for Galha Ford – Liu Keh

- 12 – December, 186 pages. Contents include:

Programmes from abroad: The Bolshoi ballet in China – Jack Chen

Beethoven interpreted by the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra – Chao Feng

Stories: Mother and daughter – Li Chun

1960:

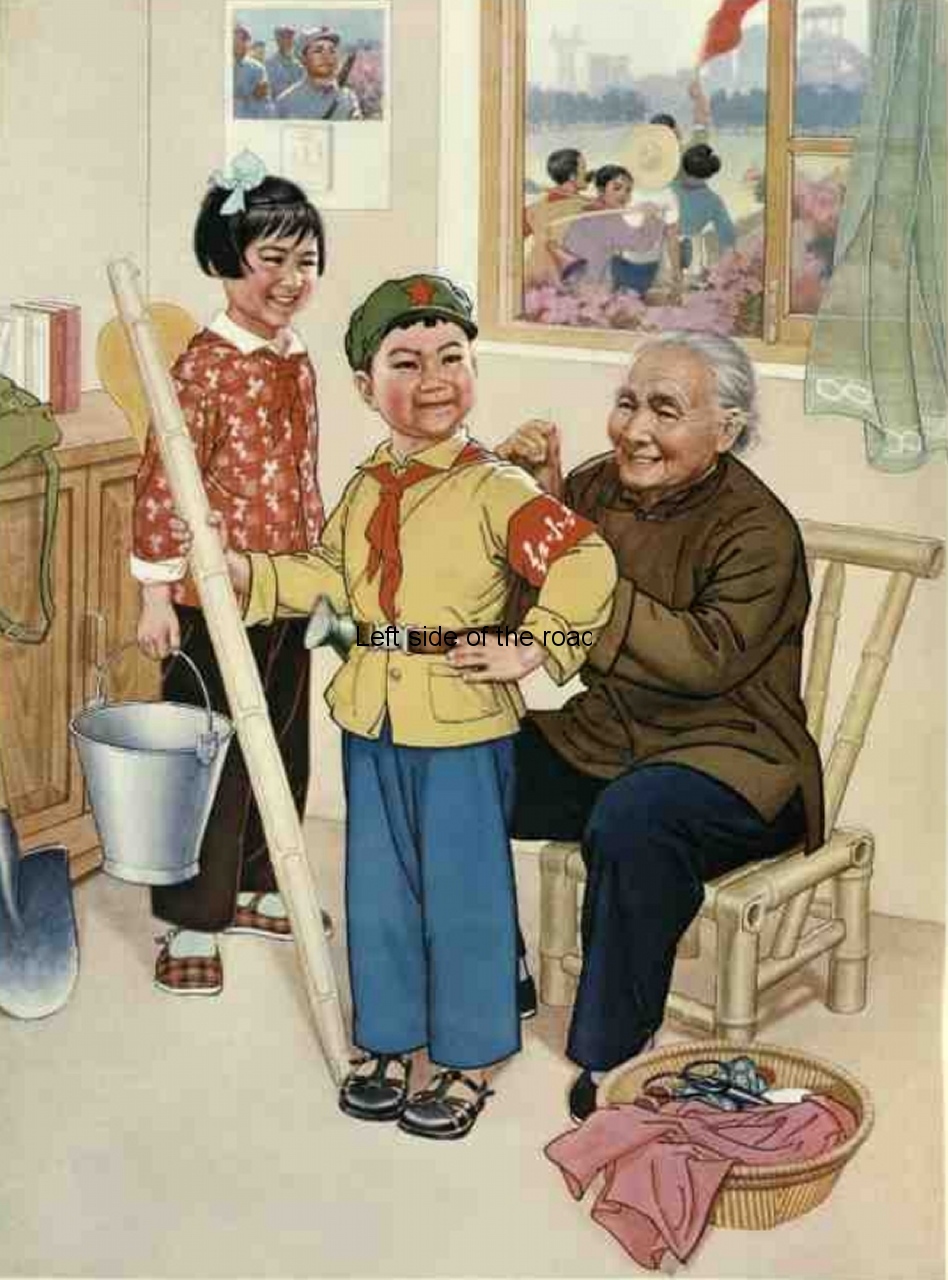

Be a good, virtuous student

- 1 – January. (Not yet available)

- 2 – February, 144 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: Modern Chinese short stories – Sung Shuang

Pages from history: Forty days on the banks of Tungting Lake – Chang Shu-chih

Travel notes: A thousand li across Southern Sinkiang – Pi Yeh

- 3 – March, 150 pages. Contents include:

The song of youth (first instalment of a novel) – Yang Mo

Caught in the flood (a reportage) – Kuo Kuang

Notes on literature and art: The Great hall of the People in Peking – Liang Szu-cheng

- 4 – April, 160 pages. Contents include:

New folk songs

Raise higher the banner of Mao Tse-tung’s Thought on literature and art – Lin Mo-han

Notes on literature and art: The museum of Chinese History – Wang Li-hui

- 5 – May, 148 pages. Contents include:

Essays in memory of the Martyrs – Lu Hsun

Notes on literature and art: Our art is advancing with the time – Tsai Jo-hung

Chekhov’s anniversary

150th anniversary of the birth of Frederic Chopin

- 6 – June, 162 pages. Contents include:

Anecdotes of the Long March: A pair of cloth shoes – Chiang Yao-huei

Cartoon films: Mural on a Commune yard wall (a cartoon film scenario)

The new cartoon films – Hua Chun-wu

- 7 – July, 166 pages. Contents include:

Hail the people’s spring: The chain reaction of the anti-Imperialist struggle – Kuo Mo-jo

Poetry for Cuba: Cuba, I salute you – Emi Hsiao

Notes on literature and art: Art exhibition of the People’s Liberation Army – Tuan Chang

- 8 – August, 176 pages. Contents include:

Japanese writers’ delegation in China: Chinese writers stand together with the fighting Japanese writers – Mao Tun

Traditional operas: The revival of two operas – Chang Keng

Notes on literature and art: Literary ties between China and Latin America – Chou Erh-ju

Chairman Mao Tse-tung’s talk with the Japanese Writers’ Delegation

Ar activities in the anti-US Imperialism Propaganda Week: Smash the US Paper Tigers – Chou Wei-chih

Exhibitions of modern Japanese painting in Peking – Yeh Chien-yu

- 10 – October, 206 pages. Contents include:

Greetings to the Third Congress of Chinese Literary and Art Workers – Lu Ting-yi

The Builders (first instalment of a novel) – Liu Ching

The Chinese style in art – a review of the National Exhibition of Art – Teng Wen

- 11 – November, 170 pages. Contents include:

Reflect the age of the Socialist Leap Forward, promote the Leap Forward of the Socialist Age! Mao Tun

A writer’s responsibility – Sha Ting

Red night (a story) – Hsiao Mu

- 12 – December, 216 pages. Contents include:

Study Comrade Mao Tse-tung’s most firm, most thorough-going Revolutionary spirit

Mirages and sea-markets (a sketch) – Yang Shuo

A short introduction to Old Chinese fables

1961:

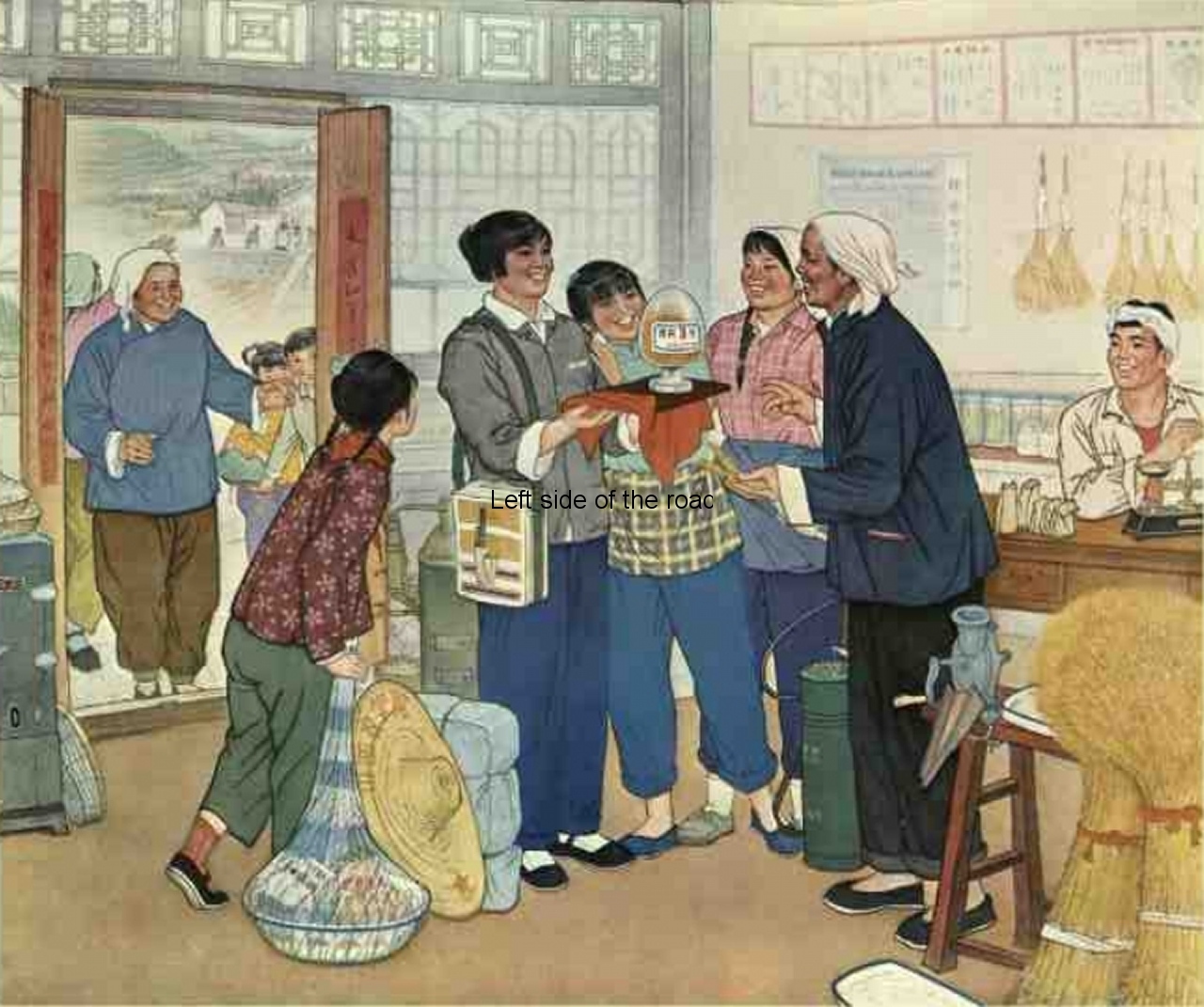

The People’s Commune is good

- 1 – January, 198 pages. Contents include:

In his mind a million bold warriors – a reminiscence of the fighting life of Chairman Mao by one of his fighting comrades, Yen Chang-Lin

Commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the death of Leo Tolstoy

Tearing the mask off the U.S. armed forces – the story of an incursion of US naval forces on Chinese territory in October 1945

- 2 – February (Not yet available)

- 3 – March (Not yet available)

- 4 – April (Not yet available)

- 5 – May (Not yet available)

- 6 – June (Not yet available)

- 7 – July (Not yet available)

- 8 – August (Not yet available)

- 9 – September (Not yet available)

- 10 – October (Not yet available)

- 11 – November (Not yet available)

- 12 – December (Not yet available)

1962:

1963:

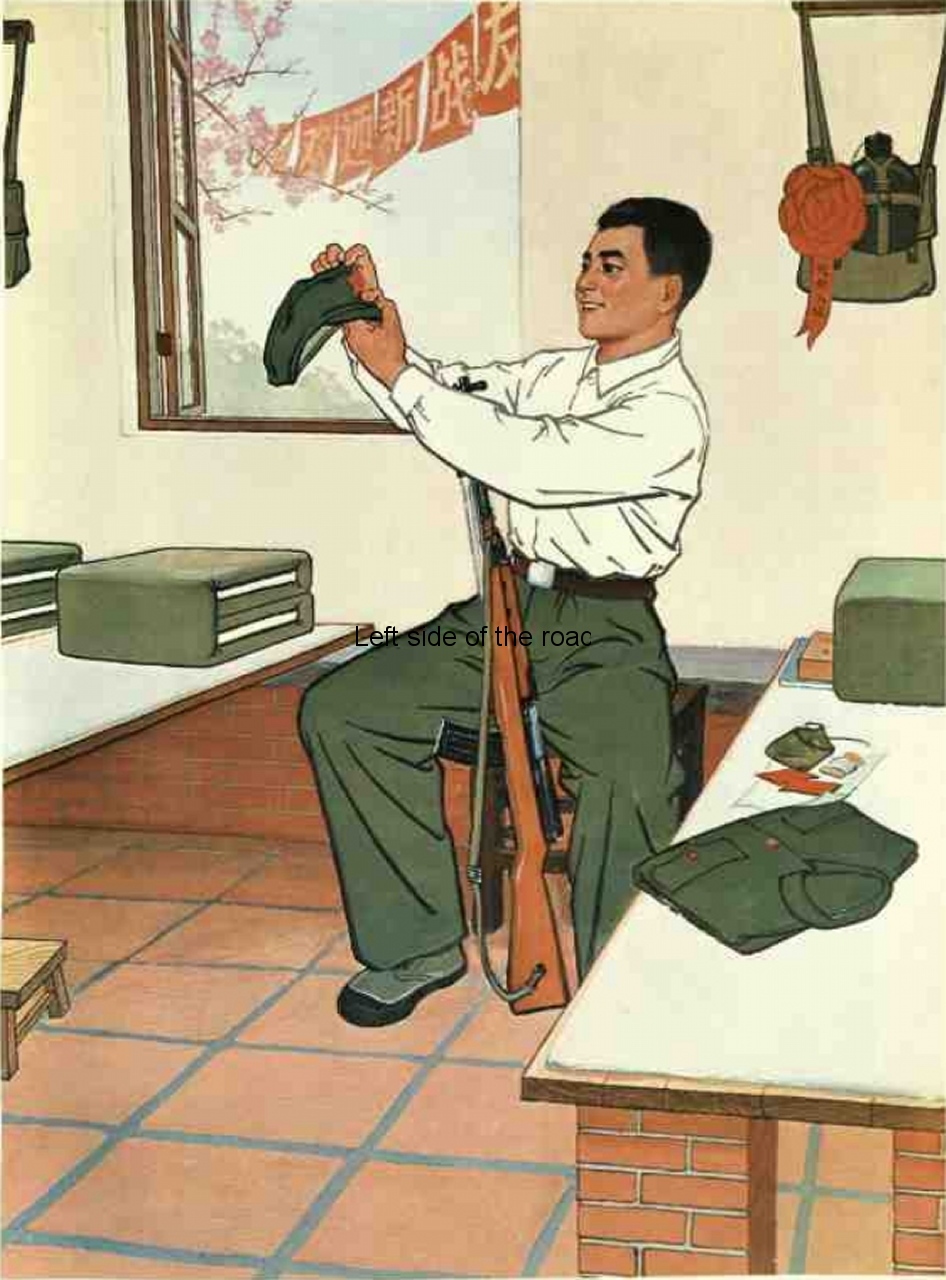

A good pupil

- 1 – January (Not yet available)

- 2 – February (Not yet available)

- 3 – March (Not yet available)

- 4 – April (Not yet available)

- 5 – May (Not yet available)

- 6 – June (Not yet available)

- 7 – July, 128 pages. Contents include:

A woman writer of distinction – the peasant writer Ju Chih-chuan

Face designs in Chinese Opera

Chinese translations of Latin American literature

- 8 – August, 144 pages. Contents include:

On the militant task of China’s literature and art today

Stormy Years – a novel about the Chinese people’s war of resistance against Japanese aggression

How the ‘Bai’ Learned a Lesson – Uighur folk tale

Stormy Years – more excerpts from the novel

The Collected Works of Chu Chiu-pai (Qu Qiubai) – later to be criticised during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76)

The Collected Works of Hung Shen – dramatist and film maker

- 10 – October, 122 pages. Contents include:

Heroes of the marshes – a classic tale of peasant resistance in 12th century China (an excerpt)

Japanese literary works in Chinese translation

Some thoughts on cartooning

- 11 – November, 126 pages. Contents include:

An interview with the playwright Tsao Yu (Cao Yu) – he was also criticised during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76)

Two stories by Lu Hsun – The white light and The lamp that was kept alight

Remembering Dark Africa – three poems from a collection by Han Pei-ping

- 12 – December, 136 pages. Contents include:

Two short stories by Yu Ta-fu (Yu Dafu) – Arbutus Cocktails and Flight

Truth, imagination and invention

Passages from an autobiography of Chi Pai-shih (Qi Baishi) – a painter in the traditional style

1964:

The magnificent hydroelectric power station on the Xi’an river

- 1 – January, 134 pages. Contents include:

Writings of the last generation – Wang Tung-chao and Wu Tsu-hsiang

Introduction to classical painting

Notes on drama

- 2 – February, 136 pages. Contents include:

Excerpt from the novel ‘The Builders’ by Liu Ching

Writings of the last generation – Yang Chen-sheng

Notes on art

- 3 – March (Not yet available)

- 4 – April (Not yet available)

- 5 – May (Not yet available)

- 6 – June (Not yet available)

- 7 – July (Not yet available)

- 8 – August (Not yet available)

- 9 – September (Not yet available)

- 10 – October (Not yet available)

- 11 – November (Not yet available)

- 12 – December (Not yet available)

1965:

Listen to Chairman Mao

- 1 – January, 128 pages. Contents include:

Stormy seas – Chi Ping

Portraying the new people of our age

The lean horse (play) – An Wen

- 2 – February, 118 pages. Contents include:

Pillar of the south (poem) – Tsai Jo-hung

Sisters-in-law – Hao Jan

Reportage in contemporary Chinese writing

- 3 – March (Not yet available)

- 4 – April (Not yet available)

- 5 – May (Not yet available)

- 6 – June (Not yet available)

- 7 – July (Not yet available)

- 8 – August (Not yet available)

- 9 – September (Not yet available)

- 10 – October (Not yet available)

- 11 – November (Not yet available)

- 12 – December, 210 pages. Contents include:

An episode from the years of war – Li Ying-ju

The blacksmith and his daughter – Liu Keh

Dream of a gold brick

1966:

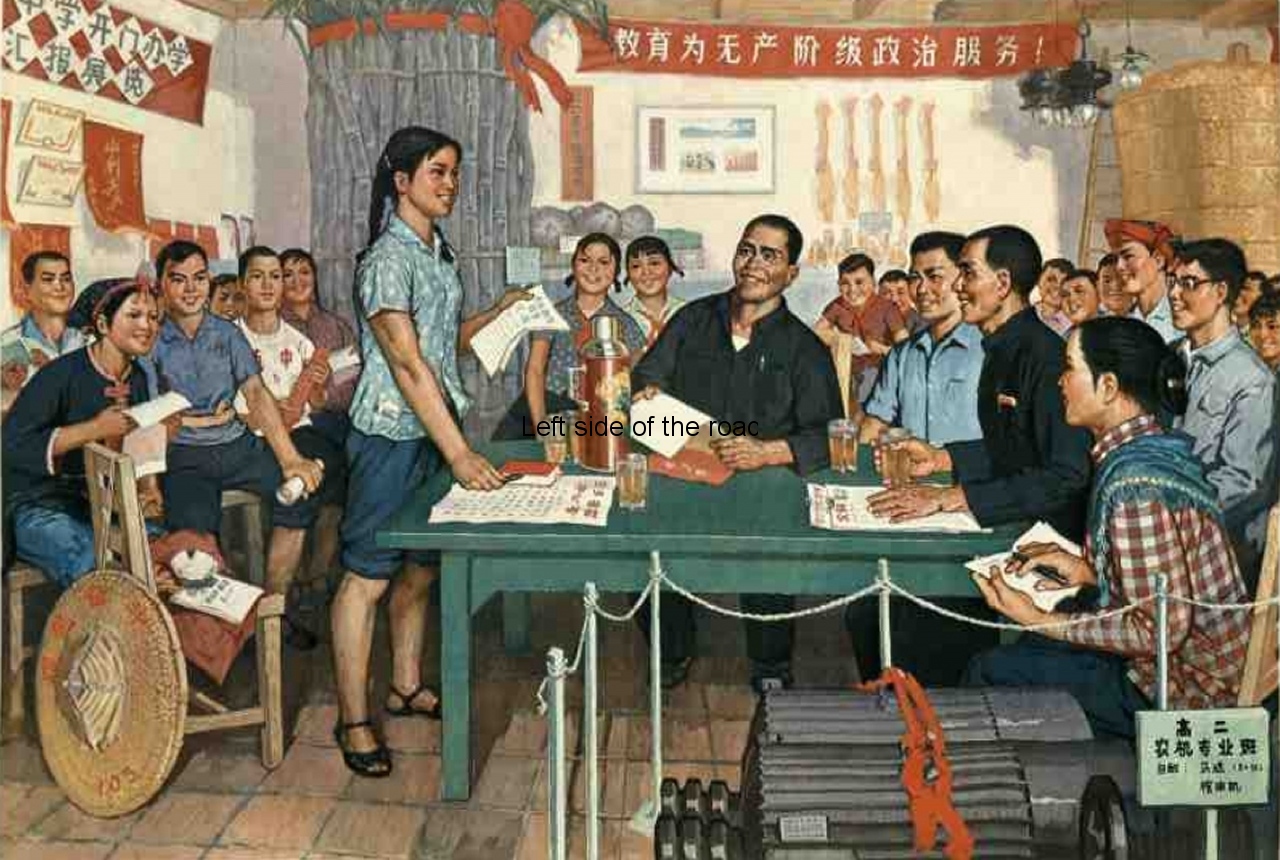

Studying for the Revolution

- 1 – January, 136 pages. Contents include:

Taking goods to the countryside (a short comedy) – Chao Shu-jen

New Sculptures – Fu Tien-chou

- 2 – February (Not yet available)

- 3 – March (Not yet available)

- 4 – April (Not yet available)

- 5 – May (Not yet available)

- 6 – June, 138 pages. Contents include:

Some problems concerning dramas

On revolutionary modern themes – Tao Chu

Introducing a classical painting: Hsu Ku’s ‘Willow and Mynahs’ – Hu Ching-yuan

- 7 – July (Not yet available)

- 8 – August, 162 pages. Contents include:

Long Live the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

China in the midst of high-tide of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

The Revolutionary Ballet ‘The White-Haired Girl’

- 9 – September (Not yet available)

- 10 – October, 180 pages. Contents include:

Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art – Mao Tse-tung

Songs in praise of Chairman Mao

Repudiate Chou Yang’s revisionist programme for literature and art – Wu Chi-yen

- 11 – November, 139 pages. Contents include:

Celebrate the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution – articles

Poems

Notes on literature

- 12 – December, 147 pages. Contents include:

Long Live Chairman Mao, long life, long, long life to him – The great leader celebrates National Day with the Revolutionary Masses.

1967:

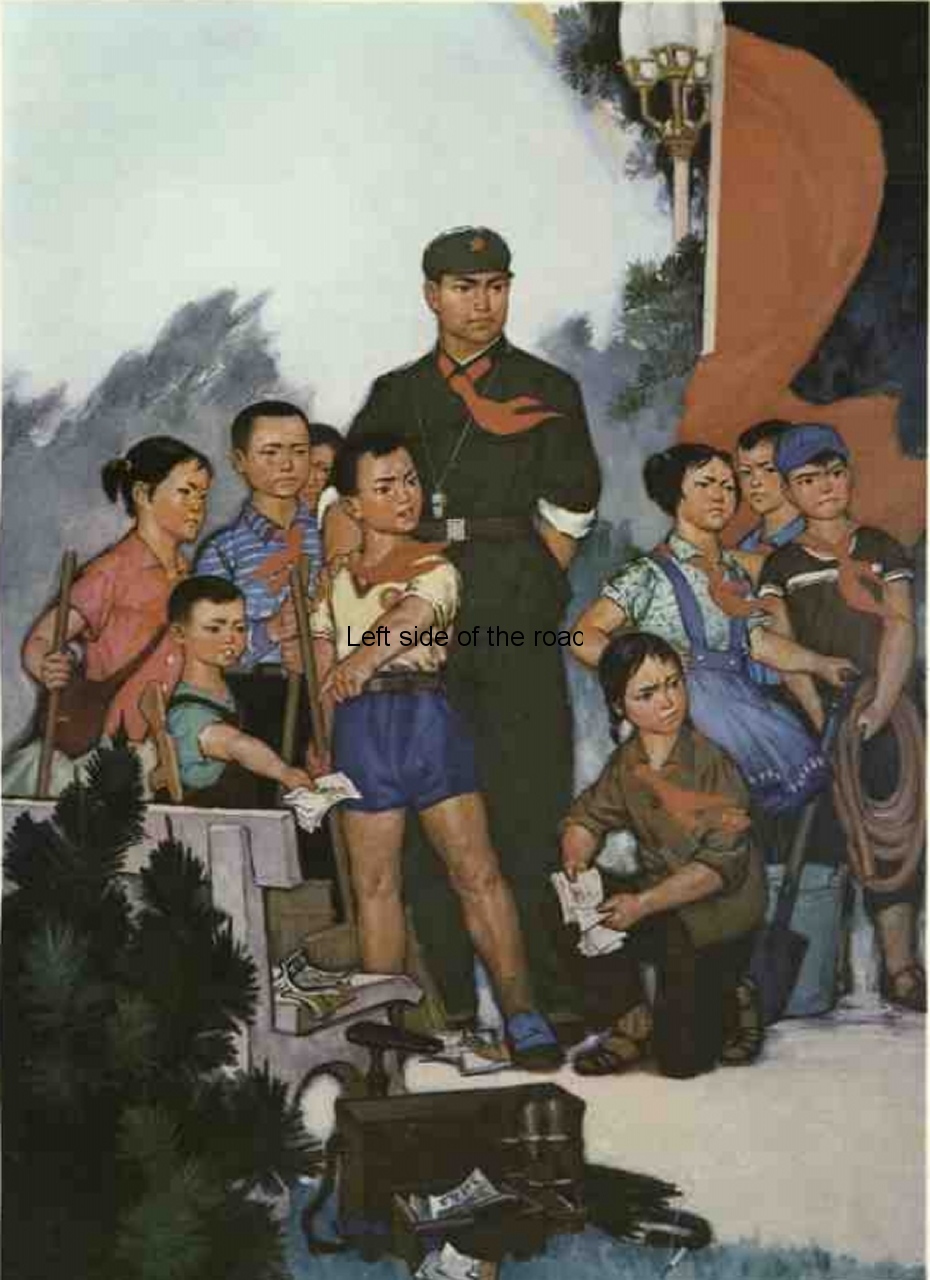

Concentrate your hatred

- 1 – January, 162 pages. Contents include:

An issue almost completely devoted to a commemoration and celebration of the work and life of the writer Lu Hsun

- 2 – February. (Not yet available)

- 3 – March, 158 pages. Contents include:

The Red Lantern which cannot be put out – Kao Liang

Repudiation of the Black Line: On the Counter-revolutionary double-dealer Chou Yang – Yao Wen-yuan

Red Guards on the Long Match

- 4 – April, 160 pages. Contents include:

Repudiation of the Black Line: Hua Chun-Yu is an old hand at drawing black anti-Party ‘artoons

The Clarion Call of the ‘January Revolution’

We must revolutionize our thinking and then revolutionize sculpture

Articles and a photo spread about the improved clay sculptures in the famous ‘Rent Collection Courtyard’ collection.

- 5-6 – May-June, 200 pages. Contents include:

Tributes to Norman Bethune:

In memory of Norman Bethune – Mao Tse-tung

A Great Communist Fighter – Yeh Ching-shan

Repudiation of the Black Line: The real meaning of Chou Yang’s ‘Theory of broad subject-matter

- 7 – July, 138 pages. Contents include:

On the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution: Patriotism or national betrayal

Literary and art workers repudiate the top Party person in authority taking the capitalist road

The death knell of imperialism is tolling – Feng Lei

- 8 – August, 226 pages. Contents include:

Talks at the Yenan Forum of Literature and Art – Mao Tse-tung

Fight to safeguard the Dictatorship of the Proletariat

On the Revolution in Peking Opera – Chiang Ching

Taking the Bandits’ Stronghold (Model Peking Opera) Script and 12-page set of colour photos.

Articles by Comrade Mao Tse-tung:

Letter to the Peking Opera Theatre after seeing ‘Driven to join the Liangshan Mountain Rebels’

Give serious attention to the discussion of the film ‘The life of Wu Hsun’

Letter concerning studies of ‘The dream of the Red Chamber’

Two instructions concerning literature and art

- 10 – October, 163 pages. Contents include:

On ‘Let a Hundred Flowers Blossom, let a Hundred Schools of Thought contend’ – Mao Tse-tung

Raid on the White Tiger Regiment (a modem Peking opera)

For ever uphold the orientation that literature and art must serve the workers, peasants and soldiers – Wang Hsiang-tung

- 11 – November, 160 pages. Contents include:

Shachiapang (a revolutionary Peking opera)

Learn from revolutionary heroes

Let us write songs in praise of the heroic workers, peasants and soldiers

- 12 – December, 138 pages. Contents include:

Comments on Tao Chu’s two books – Yao Wen-yuan

Literary criticism and repudiation: The ringleader in peddling a ‘Literature and Art of the whole people’

Performance in China of the Vietnamese acrobatic troup

1968:

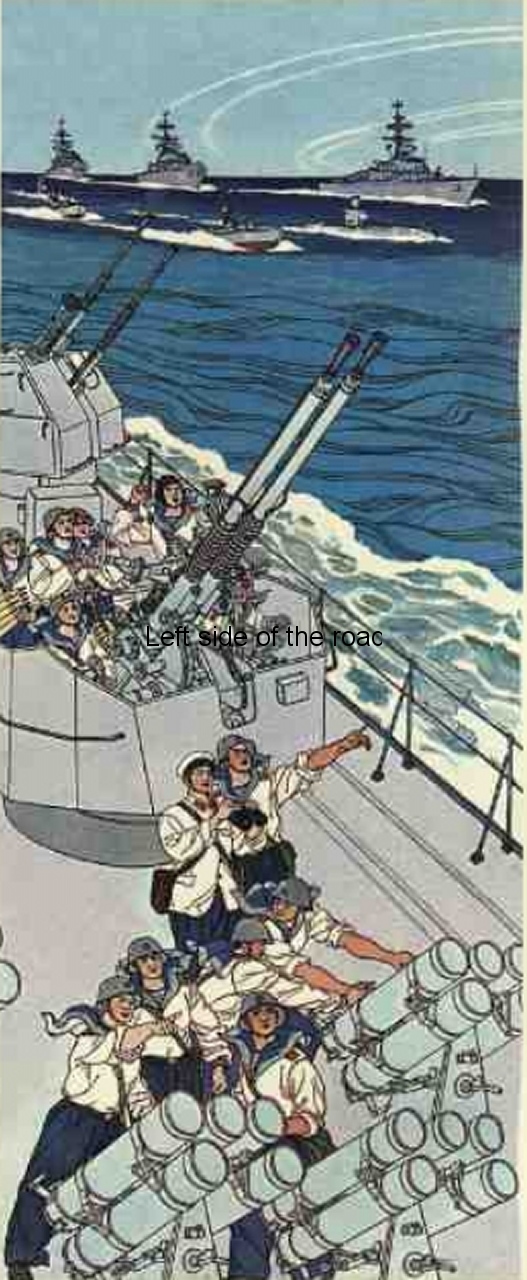

Everyone is a soldier in defence of the fatherland

- 1 – January, 132 pages. Contents include:

The culture of New Democracy – Mao Tse-tung

Literary criticism and repudiation: Expose the counter-revolutionary features of Sholokhov – Shih Hung-yu

Fighting South and North (a film scenario)

- 2 – February, 130 pages. Contents include:

Literary criticism and repudiation: A manifesto of opposition to the October Revolution – Hung Hsueh Chun

Tear off the mask of the ‘Culture of the entire People’ – Fan Hsiu-wen

- 3 – March, 172 pages. Contents include:

Hail the mass publication of Chairman Mao’s works

Forum on the clay sculptures ‘Family histories of airmen’

Literary criticism and repudiation: Apologist for Bukhrarin, agent of the kulaks – Li Ching

- 4 – April, 134 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: Go among the workers, peasants and soldiers

Literary criticism and repudiation: The banner of the October Revolution is invincible – Chung Yen-ping

- 5 – May, 134 pages. Contents include:

Speech at the Chinese Communist Party‘s National Conference on propaganda work – Mao Tse-tung

Literary criticism and repudiation: Expose the nature of the Soviet Revisionists’ vaunted ‘humanism’ – Fan Hsiu-wen

- 6 – June, 118 pages. Contents include:

Statement by Comrade Mao Tse-tung, in support of the Afro-American struggle against violent oppression

Literary criticism and repudiation: A review of ‘Days and Nights’ – Hsieh Sheng-wen

Repudiate Tao Chu’s Revisionist programme for literature and art

Commemorate the 26th Anniversary of the Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art: Let Our theatre propagate Mao Tse-Tung’s thought forever – Ya Hai-jung

Unfold mass repudiation, defend Chairman Mao’s Revolutionary line in literature and art – Hsieh Sheng-wen

Revolutionary literature and art must serve the workers, peasants and soldiers

- 9 – September. (Not yet available)

- 10 – October, 120 pages. Contents include:

Forum on literature and art: Mao Tse-tung’s Thought is a beacon for Revolutionary literature and art – Chen Ping and Li Ming-hui

The fundamental task of Socialist literature and art – Sun Kang

We shall always sing of the Red Sun in our hearts – Chou Kuo

Literature and art must serve Proletarian Politics – Hsia Lin-ken

- 11 – November, 132 pages. Contents include:

The working class must exercise leadership in everything – Yao Wen-yuan

Notes on art: Greet the new era of Proletarian Revolutionary literature and art – Ting Hsueh-lei

A brilliant example of making foreign things serve China – Kao Chang-yin

-

- Supplement: “Communique of the Enlarged 12th Plenary Session of the Eighth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China”, Adopted on October 31, 1968, 12 pages.

- 12 – December, 139 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: The course of a militant struggle – Wen Wei-ching

Magnificent ode to the worker, peasant and soldier heroes

1969:

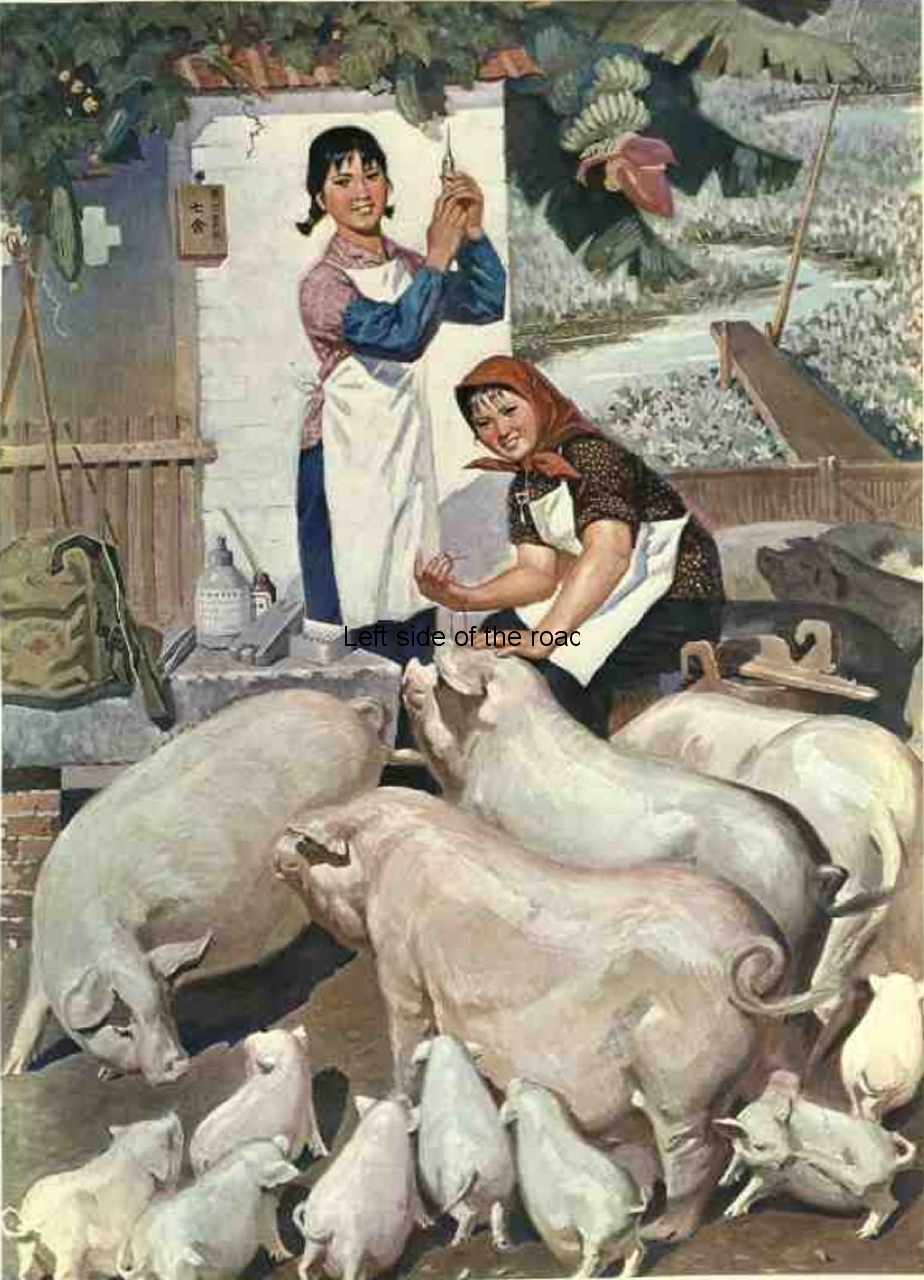

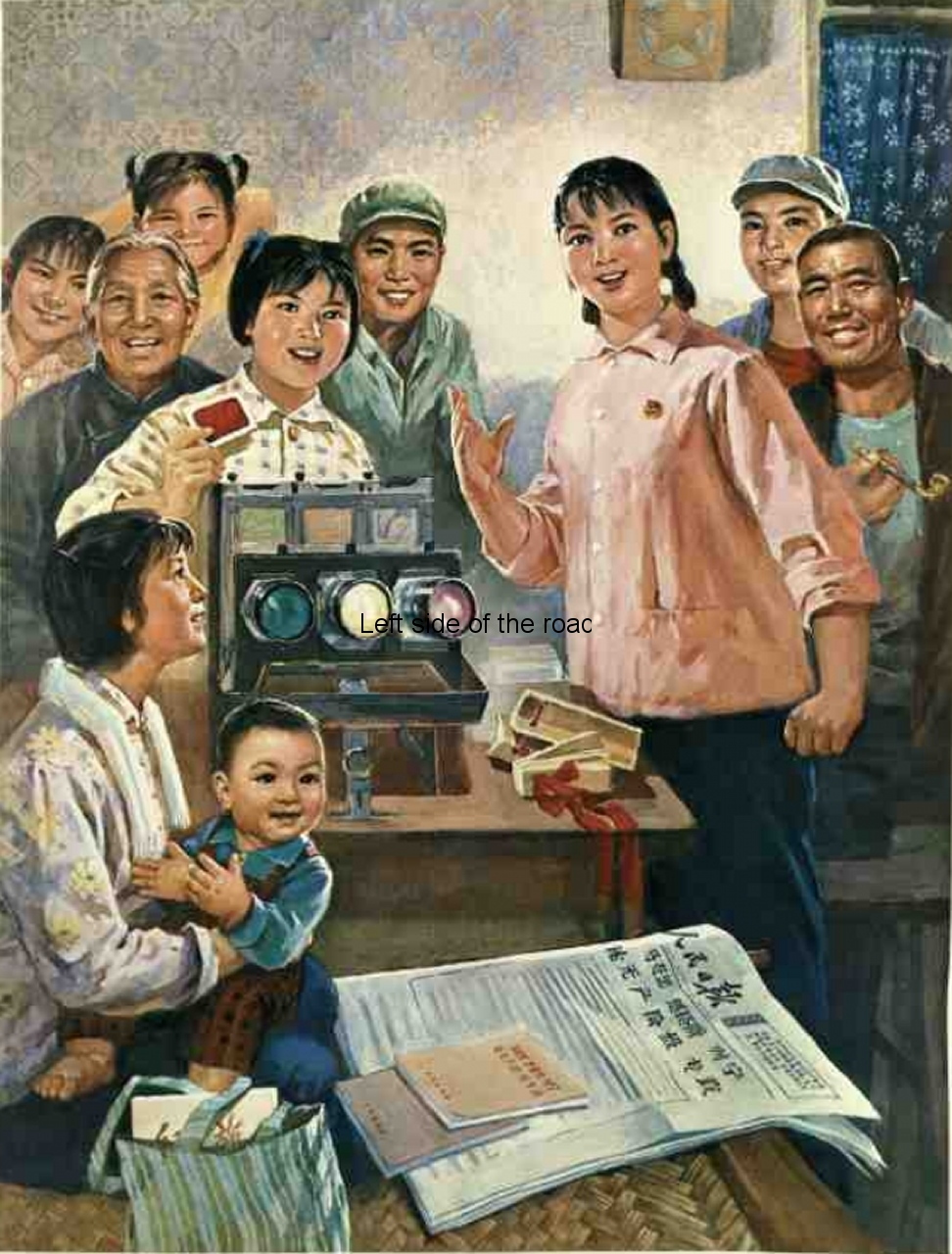

Support the rural population and serve 500 million peasants

- 1 – January, 120 pages. Contents include:

On the Docks (a revolutionary model Peking opera)

Literary criticism and repudiation: Peasants criticise the Revisionist line in literature and art

- 2 – February. (Not yet available)

- 3 – March, 120 pages. Contents include:

Revolutionary stories: Debate over a piece of land – Lo Chung-tung

Literary criticism and repudiation: Lackey of imperialism, revisionism and reaction; renegade to Socialism – Chen Mou

- 4 – April, 120 pages. Contents include:

Revolutionary stories: The story of protecting Chairman Mao’s portrait

Literary criticism and repudiation: We are history’s witnesses

Unmask the ‘Leader of the Workers’ Movement’

-

- Supplement: ‘Press Communique of the Secretariat of the Presidium of the Ninth National Congress of the Communist Party of China, April 1, 1969.

- Supplement: Fold-out photo of the newly-built Yangtse River Bridge at Nanking.

- 5 – May, 122 pages. Contents include:

Red detachment of women (a revolutionary model ballet)

On the revolution in education: How the old poor peasant set up a school

Literary criticism and repudiation: Sinister exemplar of Liu Shao-chi’s theory ‘Exploitation has its merit’

-

- Supplement: ‘Press Communique of the Secretariat of the Presidium of the Ninth National Congress of the Communist Party of China’, April 24, 1969.

- 6 – June, 123 pages. Contents include:

‘Guerrillas of the plain’ (a film story)

Song of new horizons (Poem) – Chi Nien-tung

‘A soldier and an old woman’ (Short story) – Sha Hung-ping

- 7 – July, 195 pages. Contents include:

(Most of this edition devoted to the 9th Congress)

Report to the Ninth National Congress of the Communist Party of China – Lin Piao

The Constitution of the Communist Party of China

- 8 – August. (Not yet available)

- 9 – September, 120 pages. Contents include:

Revolutionary stories: Moistened by rain and dew, young crops grow strong

Notes on art: Red artist-soldiers and the revolution in fine arts education

- 10 – October, 120 pages. Contents include:

Ugly performance of self-exposure – Chung Jen

Revolutionary stories: Raising seedlings

Literary criticism and repudiation: Comments on Stanislavsky’s ‘System’

Speech by Premier Chou En-lai – at the reception celebrating the 20th Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China

Fight for the further consolidation of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat – in celebration of the 20th Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China

1970:

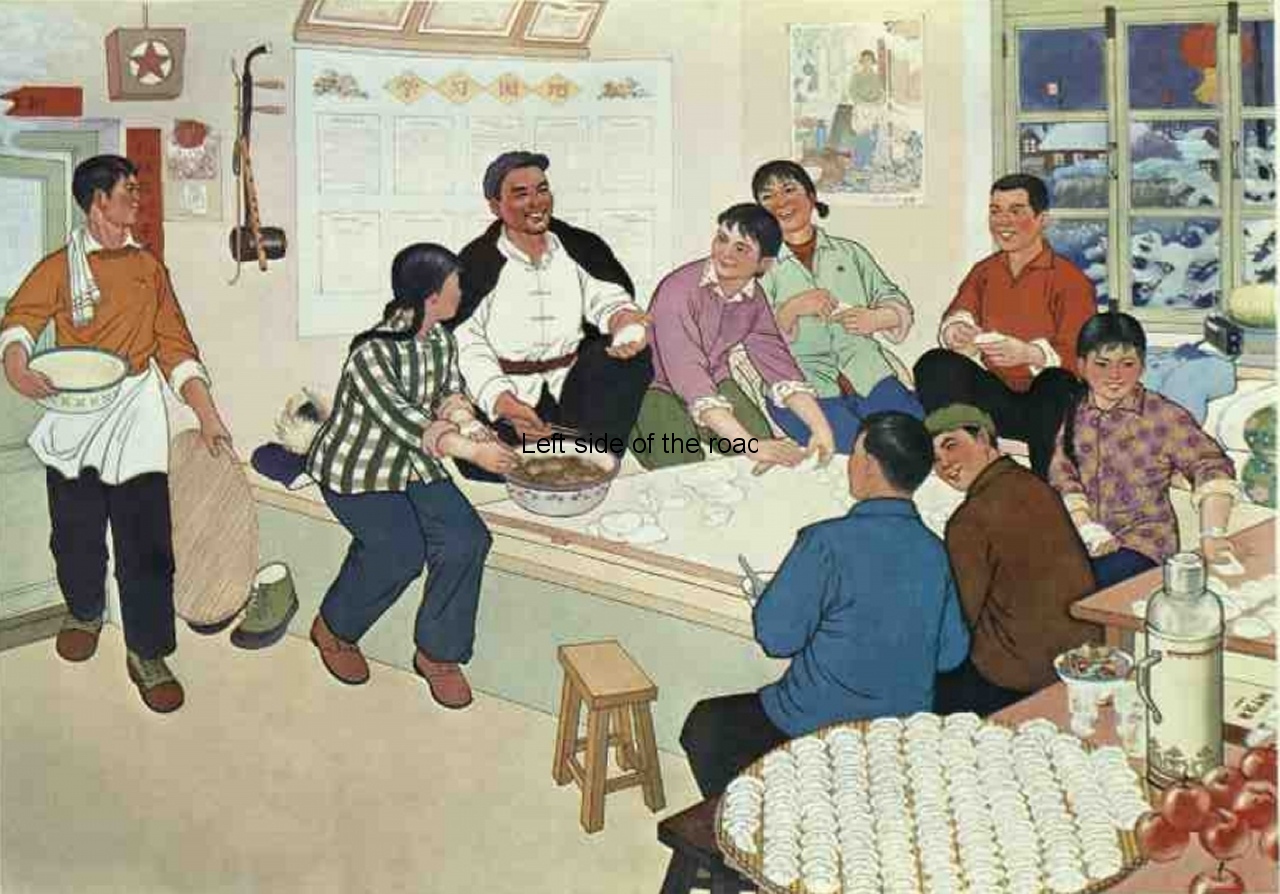

Learn from Comrade Wang Guofu

- 1 – January. (Not yet available)

- 2 – February, 124 pages. Contents include:

‘Heroic sisters on the grassland’ (an animated cartoon in colour)

Notes on art: Drawn from life, but on a higher plane

Brilliant example of the Revolution in Peking Opera Music

- 3 – March, 130 pages. Contents include:

A red heart loyal to Chairman Mao

Revolutionary stories: A new family

Literary criticism and repudiation: A reactionary novel which commemorated an erroneous line

- 4 – April, 128 pages. Contents include:

A cock crows at midnight (a puppet film scenario)

Literary criticism and repudiation: On Lau Shaw’s ‘City of the cat people’

- 5 – May, 134 pages. Contents include:

Literary criticism and repudiation: Revolutionary war is excellent

The world’s people love Chairman Mao

To Great Chairman Mao

The era of Chairman Mao

-

- Supplement: ‘China successfully launches its first man-made Earth satellite’, press communique, April 25, 1970.

- 6 – June, 150 pages. Contents include:

Leninism or Social-Imperialism?

Notes on art: Singing battle songs, boldly press on – Niu Chin

The stagecraft of a model Revolutionary Opera -Shu Hao-chin

-

- Supplement: ‘People of the World, unite and defeat the U.S. aggressors and all their running dogs!”, statement by Mao Tsetung, May 20, 1970, 4 pages.

- 7 – July. (Not yet available)

- 8 – August, 136 pages. Contents include:

In Commemoration of the 28th Anniversary of the publication of ‘Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art’: Remould world outlook

The Red Lantern (May 1970 script)

Literary criticism and repudiation: The Red Army, led by Chairman Mao is an army of heroes – Chung An

Essays: Always marching along the road of serving the workers, peasants and soldiers

- 10 – October, 112 pages. Contents include:

‘Worker with a loyal heart’ – Hsiang Chun

A story of Sino-Vietnamese friendship

Unforgettable days in Shihchiacha – Yan Teh-ming

- 11 – November. (Not yet available)

- 12 – December. (Not yet available)

1971:

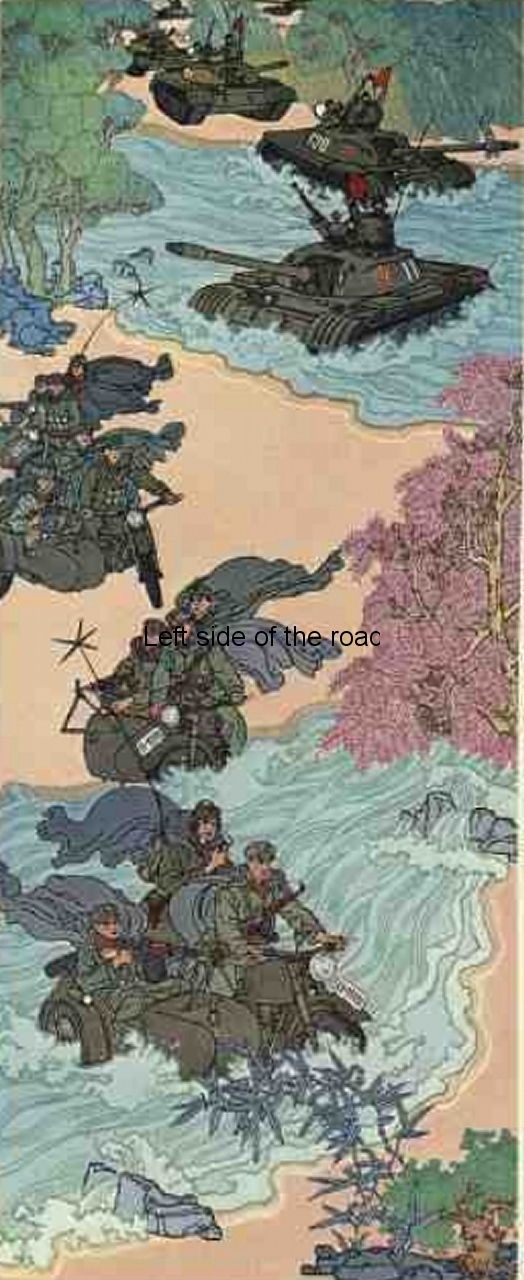

Learning how to prepare for war

- 1 – January. (Not yet available)

- 2 – February, 122 pages. Contents include:

Philosophy in the hands of the masses: Two bothers study philosophy

Notes on art: The colour film ‘Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy‘

Literary criticism and repudiation: Expose the plot of U.S. and Japanese reactionaries to resurrect the dead past – Tao Ti-wen

- 3 – March, 120 pages. Contents include:

Leader of the Hsiatingchia production brigade

Revolutionary stories: Red Hearts and Green Sprouts

News from the Vietnam Front: Sing battle songs

- 4 – April, 126 pages. Contents include:

Stories: Third Time to School – Lu Chao-hui

Raiser of sprouts – Chang Wei-wen

Poems: Our Olunchun Girl – Yu Tsung-hsin

Sketches: A night in ‘Potato’ village – Tai Mu-jen

- 5 – May, 126 pages. Contents include:

‘Tunnel Warfare’ (a film scenario)

Notes on art: A film of great beauty – Ting Yuan-chang

- 6 – June, 120 pages. Contents include:

In Commemoration of the Centenary of the Paris Commune

The principles of the Paris Commune are eternal

Battle Flag (a poem) – Yu Tsung-hsin

Salute to the literature of the Paris Commune – Hua Wen

- 7 – July, 132 pages. Contents include:

‘On the Long March with Chairman Mao‘ – Chen Chang-feng

Literary criticism and repudiation: Hero or renegade? – Hsiao Wen

- 8 – August, 144 pages. Contents include:

In his mind a million bold warriors – Yen Chang-lin

Notes on literature and art: She sings on the university platform

Fight on till victory!

- 9 – September. (Not yet available)

- 10 – October, 128 pages. Contents include:

Writings by Lu Hsun

Stories: A Madman’s Diary

The New Year’s SacrificeEssays: In Memory of Miss Liu Ho-chen

‘Fair play’ should be put off for the time being

Thoughts on the League of Left-wing writers

Lu Hsun – Pioneer of China’s Cultural Revolution – Choa Chien-jen

- 11 – November, 140 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: New archaeological finds – Hsiao Wen

A new sculpture

Literary criticism and repudiation: On the reactionary Japanese film ‘Gateway to Glory’ – Tao Ti-wen

- 12 – December, 132 pages. Contents include:

Beat the Aggressors (a film scenario)

Revolutionary reminicences: A little hero to remember – Li Chih-kuan and Chang Feng-ju

Notes on opera: In praise of the Korean People’s fight against aggression – Hsin Wen-liang

1972:

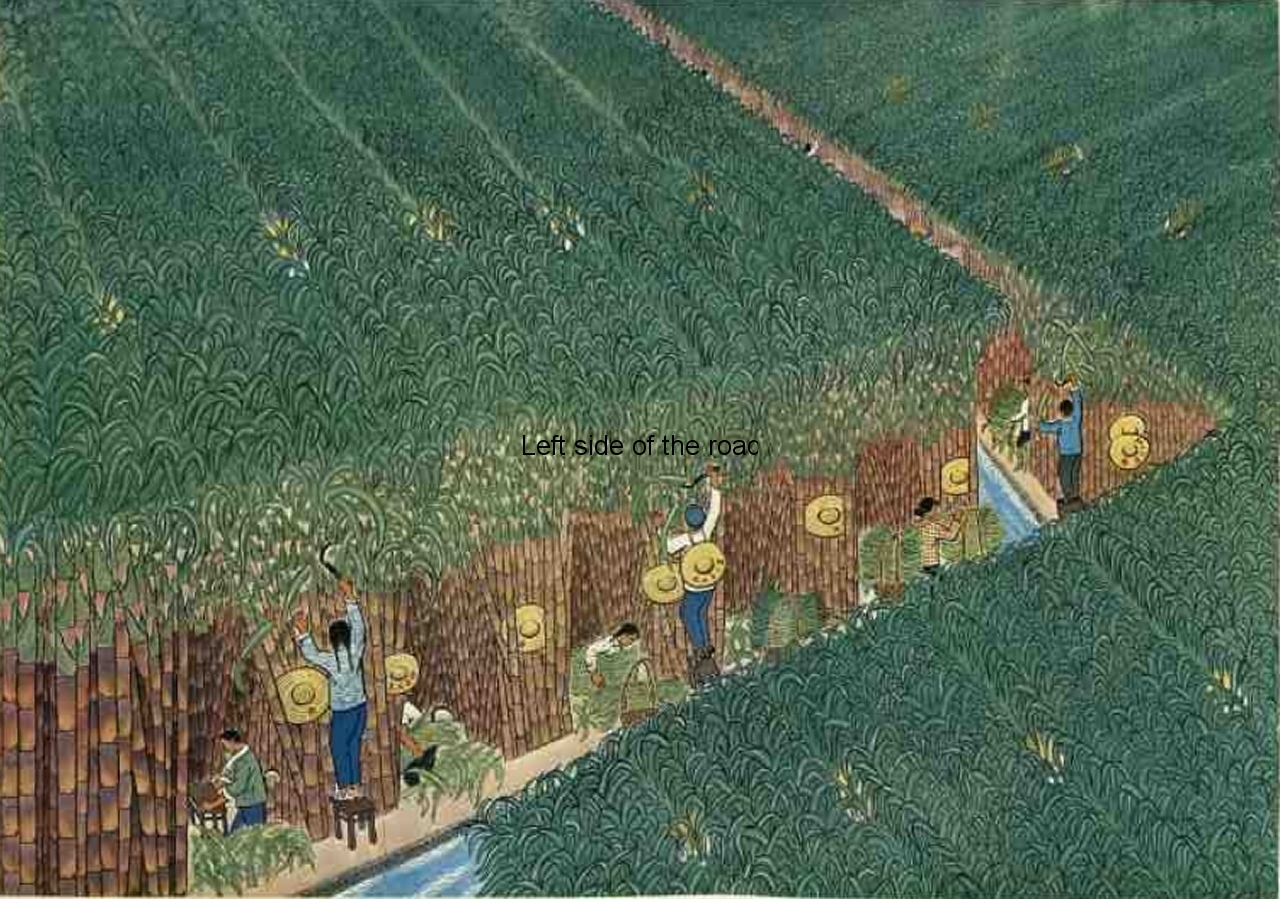

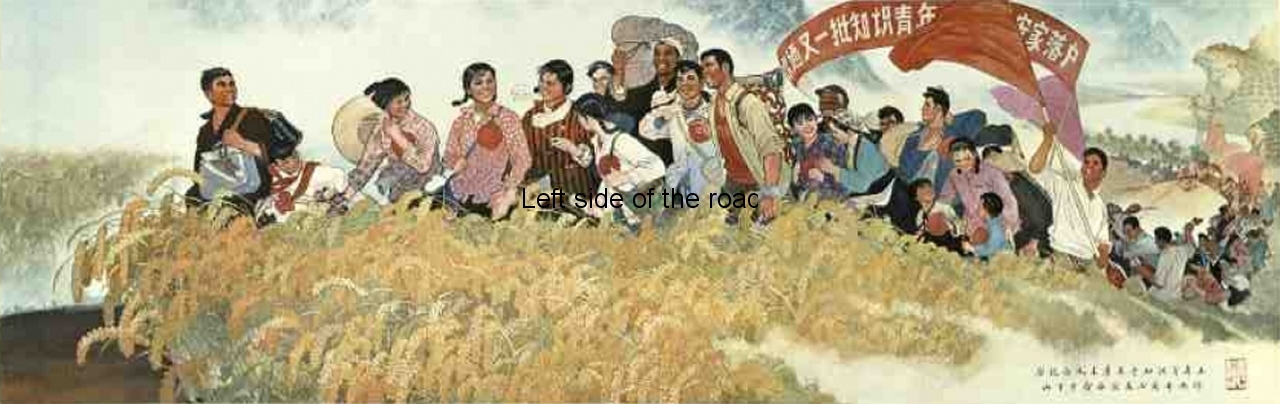

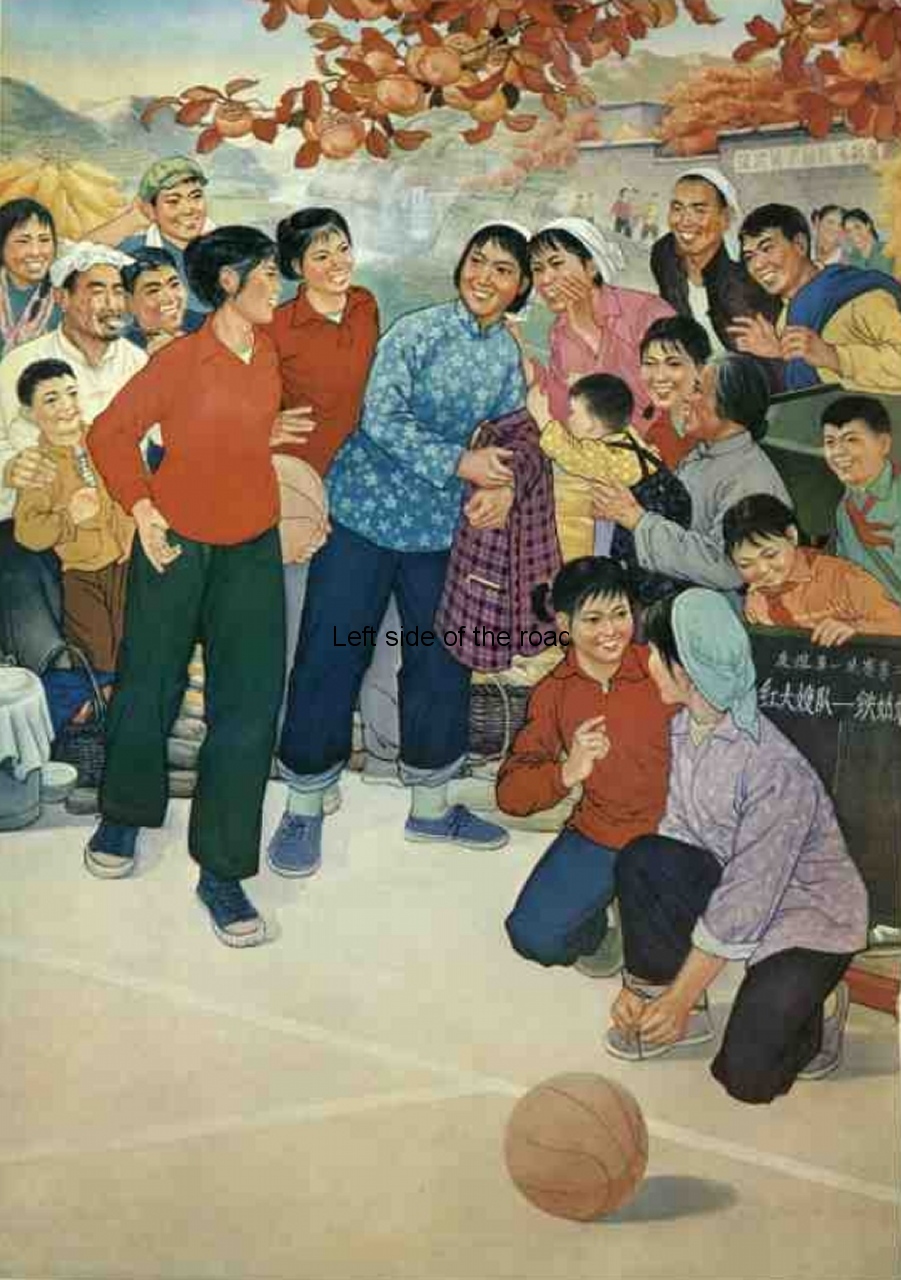

Another good harvest

- 1 – January, 118 pages. Contents include:

Two stories by Lu Hsun:

Medicine

My Old Home

Notes on the arts: Militant songs and dances from Romania – Hu Wen

Revolutionary Japanese Ballet – Shih Nan

- 2 – February, 128 pages. Contents include:

Men of Red Hill Island (a story) – Jen Pin-wu

Revolutionary reminiscences: Liu Hu-lan – Tsin Ching

Notes on art: Art recreated – Ah Jung

- 3 – March, 124 pages. Contents include:

The Stockman (an excerpt from the novel The Sun Shines Bright) – Hao Jan

Poems: Ode to ‘The Internationale’ – Chou Li-yi

Song of Discipline -Tsao Yung-hua

- 4 – April, 122 pages. Contents include:

Literary critcism: Li Po and Tu Fu as friends – Kuo Mo-jo

From the artists notebook: In praise of the heroic Vietnamese

- 5 – May, 180 pages. Contents include:

‘Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art’ by Mao Tsetung

‘On the Docks’ [Model Peking Opera] (January 1972 script.)

A Great Programme for Socialist Literature and Art – Shih Ta-wen

A Cultural Work Team on the Plateau – Ai Hung-liu

On a New Front

Light Cavalry of Culture – Hsin Hua

- 6 – June, 146 pages. Contents include:

My Childhood (excerpts from the novel) – Kao Yu-pao

Notes on literature and art: An Opera on Proletarian Internationalism – Wen Chun

How I became a writer – Kao Yu-pao

Meeting “Haguruma” Artists

- 7 – July, 168 pages. Contents include:

Song of the Dragon River (a modern Peking Revolutionary Opera)

About the film ‘The White-Haired Girl’ – Sang Hu

Wild lilies bloom red as flame (Shensi-Kansu folk song)

- 8 – August, 144 pages. Contents include:

In commemoration of the Thirtieth Anniversary of Chairman Mao’s ‘Talks at the Yenan forum on literature and art’

Adherence to Chairman Mao’s revolutionary line means victory

Our artistic heritage and our new art

A general review of new art works – Pien Cheh

Lu Hsun‘s essays: Literature and Sweat

Literature and Revolution

The Revolutionary Literature of the Chinese Proletariat and the Blood of the Pioneers

Literary criticism: Writing for the Revolution – Li Hsi-fan

- 10 – October, 160 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: Song of the Dragon River – Pei Kuo

Discovery of a 2000 year-old tomb – Wen Pien

- 11 – November, 134 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: New puppet shows – Wen Shih -ching

Innovations in traditional painting

Creating new paintings in the traditional style -Chien Sung-yen

- 12 – December, 118 pages. Contents include:

Stories by Lu Hsun: Kung I-chi

A Small Incident

In the Tavern

Literary criticism: Intellectuals of a bygone age – Li Hsi-fan

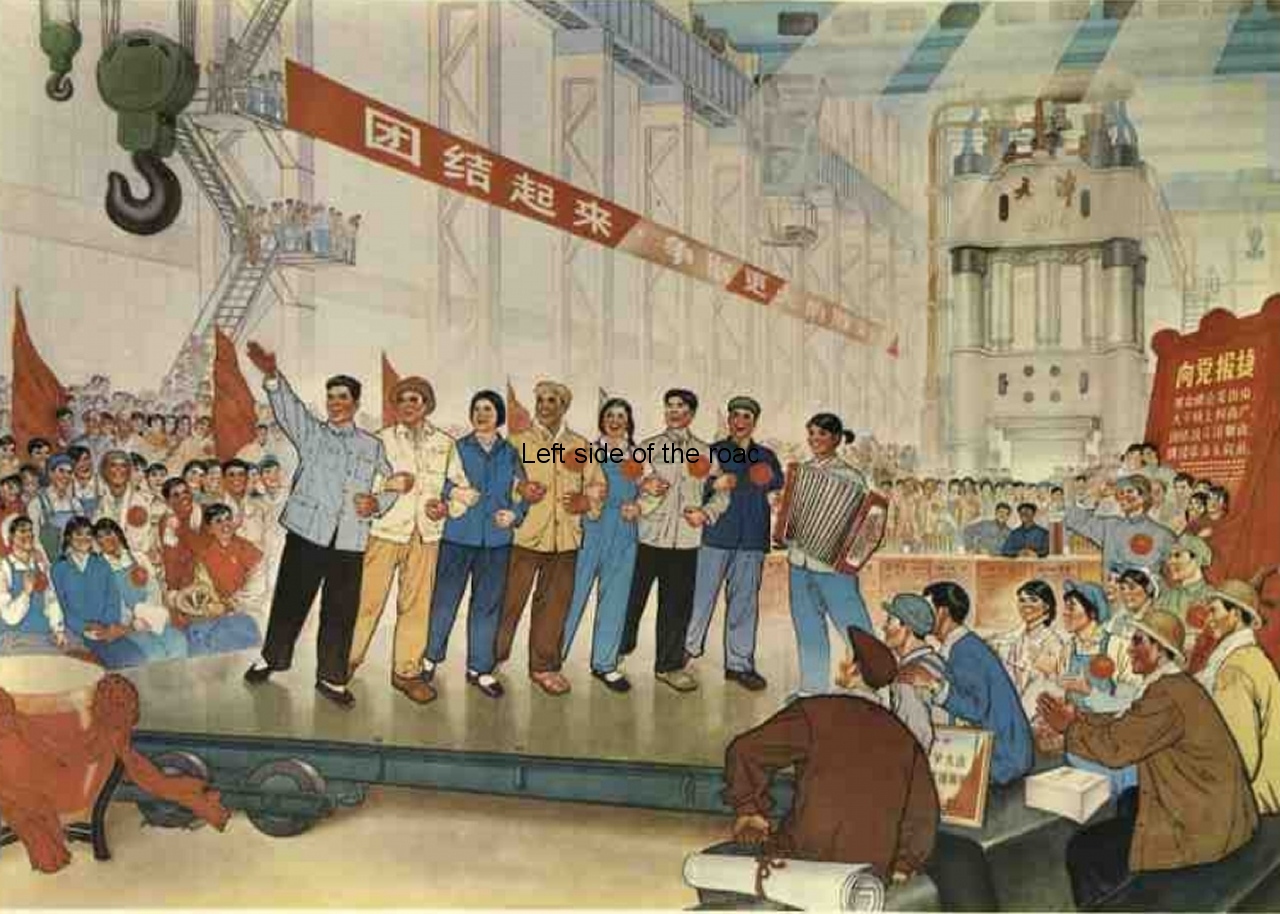

1973:

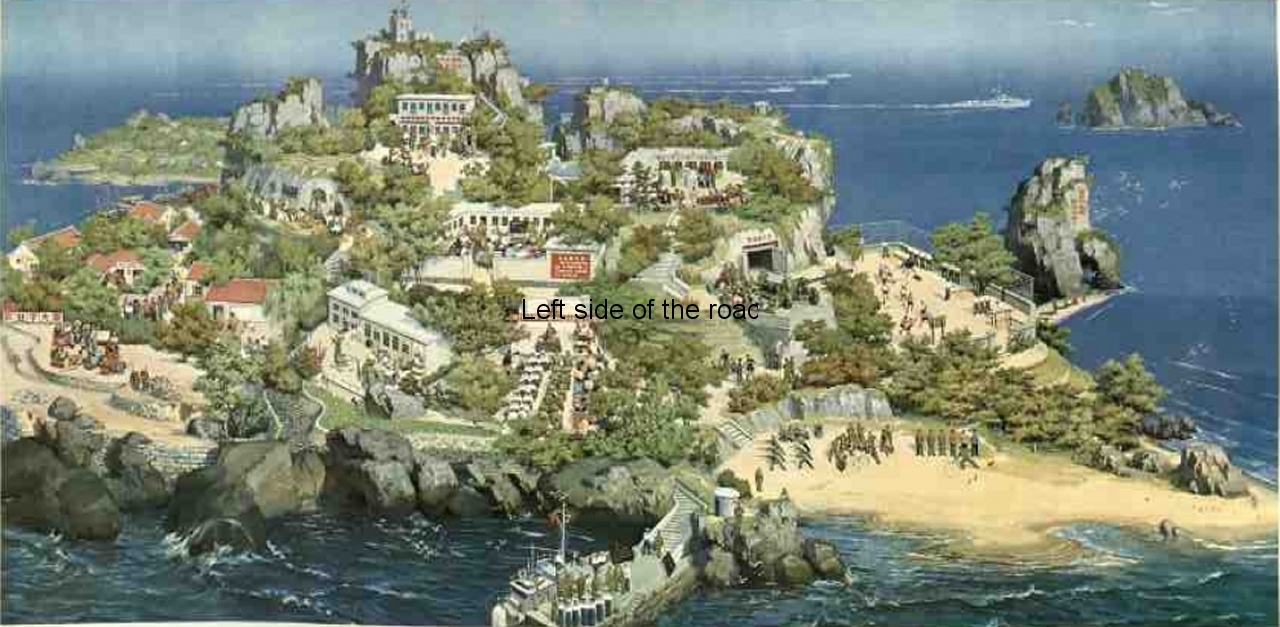

Defend and develop the island together

- 1 – January, 128 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: New developments in handicraft arts – Pien Min

Two new ivory carvings – Pien Chi

A soldier and a poet – Lin Kuo-liang

- 2 – February, 116 pages. Has a small amount of underlining. Contents include:

Short stage shows: One Big Family (a clapper-ballad) -Wang Fa and Chu Ya-nan

Camping in the Snow (a comic dialogue) – Chang Feng-chao and Tiao Cheng-kuo

Notes on art: New items on the Peking stage – Chi Szu

How we produced ‘Women Textile Workers’

- 3 – March, 140 pages. Contents include:

Raid on the White Tiger Regiment (a modern Revolutionary Peking Opera

Stories: The Breathing of the Sea – Shih Min Three young comrades – Wang An-yu

- 4 – April, 116 pages. Contents include:

Iron Ball (excerpt from a novel) – Chiang Shu-mao

Notes on art: A New Style of Bamboo Painting – Cheh Ping

- 5 – May, 122 pages. Contents include:

Drama: Half a basket of peanuts (a Shaohsing opera)

Notes on literature and art: Landmarks in the life of a great writer – Li Hsi-fan

How the Opera ‘Half a basket of peanuts’ came to be written – Chen Hua

- 6 – June, 122 pages. Contents include:

Tales: An old couple – Li Fang-ling

Between Two Collectives – Chu Kuang-Hsueh

Notes on literature and art: The forest of stone inscriptions – Shan Wen

Home of folk-songs – Hsu Fang

- 7 – July, 118 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: Some new woodcuts – Tan Shu-jen

Literary criticism: Critique of the film ‘Naturally there will be successors’ – Keng Chien

- 8 – August, 164 pages. Contents include:

Sketches: Twinkling Stars – Liu Chien-hsiang

Nets – Chang Chi

Notes on art: Exhibition of archaeological finds of the People’s Republic of China – Ku Wen

How I came to write ‘Storm warning’ – Kao Hung

Foshan scissor-cuts – Tang Chi-hsiang

Notes on literature and art: Two portrayals of Chinese Women in Lu Hsun‘s stories – Tang Tao

New paintings of the Yellow River – Chao Chuan-kuo

Shihwan stoneware – Miao Ting

- 10 – October, 120 pages. Contents include:

Stories: A young pathbreaker – Hsiao Kuan-hung

Out to Learn – Chou Yung-chuang

The Girl in the Mountains – Li Hui-hsin

Ideals in Life – Liu Yang and Hua Tung

A New Teacher – Cheng Hsuan and Yi Shih

- 11 – November, 128 pages. Contents include:

Whirling Snow Brings in the Spring (excerpt from a novel) – Chou Liang-szu

Notes on art: Productive labour and art – Hsu Huai-ching

Chinese acrobatics – Fu Chi-feng

- 12 – December, 122 pages. Contents include:

Two Poems – Hsiang Ming

Notes on art: Painting for the Revolution – Hsin Wen

Tsaidan Choma, Tibetan Singer – Hsin Hua

1974:

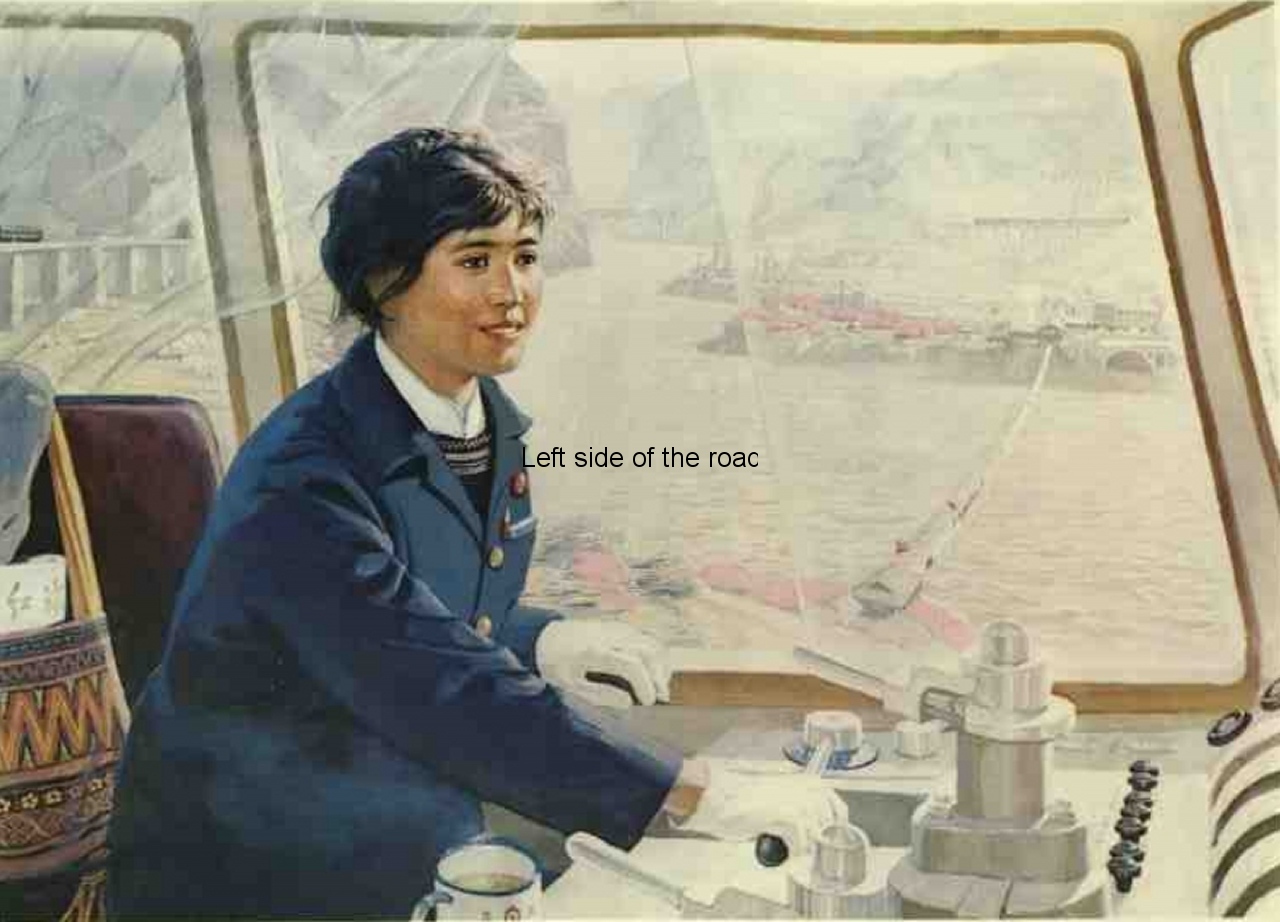

Harbour of the Fatherland

- 1 – January, 144 pages. Contents include:

Azalea Mountain (a revolutionary modern Peking opera) – Wang Shu-yuan and others

Stories:

Keep the golden bell clanging – Li Hsia

Meng Hsin-ying – Lin Chen-yi

- 2 – February, 138 pages. Contents include:

Reportage: The People of Tachai – Hu Chin

Literary criticism: ‘Create a host of new fighters’ – Shih Yi-ko

- 3 – March, 142 pages. Contents include:

A vicious motive, despicable tricks – A criticism of M. Antonioni’s anti-China film ‘China’

Exhibitions: New developments in traditional Chinese Painting – Chi Cheng

- 4 – April, 118 pages. Contents include:

Lu Hsun, a Great Fighter Against Confucianism – Lin Chih-hao

Do musical works without titles have no class Character? – Chao Hua

Interviews: Introducing the writer Hao Jan -Chao Ching

- 5 – May, 150 pages. Contents include:

Fighting on the plain (a revolutionary modern Peking opera) – Chang Yung-mei and others

On the classical heritage: ‘The Dream of the Red Chamber’ must be studied from a class

standpoint – Sun Wen-kuang

The Dream of the Red Chamber (Chapter IV) – Tsao Hsueh-chin

- 6 – June, 130 pages. Contents include:

Criticism of Lin Piao and Confucius:

Confucius, ‘Sage’ of All Reactionary Classes in China – Shih Hua-tsu

Why are we denouncing Confucius in China? -Cheh Chun

Why this hullabaloo from the Soviet Revisionist Clique? – Sa Wen

- 7 – July, 114 pages. Contents include:

Criticism and repudiation: Comments on the Shansi Opera ‘Going up to reach Peach Peak three times’ – Chu Lan

Notes on literature and art: Anti-Confucian struggles of peasant insurgents – Chi Liu

How I Made the painting ‘The Young Worker’ – Wang Hui

- 8 – August, 120 pages. Contents includes:

Notes on literature and art: Keep to the correct orientation and uphold the Philosophy of struggle – Chu Lan

Art derived from the life and struggle of the masses – Hsin Wen-tung

Paintings by one of today’s peasants – Jen Min

Criticism of Lin Piao and Confucius: Confucius’ reactionary ideas about music – Hsu Hsia-lin

Notes on art: A Decade of Revolution in Peking Opera – Chu Lan

Three young artistes in the Revolution in Peking Opera – Ah Wen

I painted the heroic Taching oil workers – Chao Chih-tien

- 10 – October, 144 pages. Contents include:

Sons and Daughters of Hsisha (excerpts from the novel) – Hao Jan

Poems by peasants of Hsiaochinchuang

Songs of oil workers

Criticism of Lin Piao and Confucius: Confucius’ reactionary views on Literature and Art – Wen Chun

- 11 – November, 122 pages. Contents include:

Storming Tiger Cliff (an excerpt from a novel) – Ktn Hsien-hung

Poems: Sparks from the welder’s torch – Yuan Chun

- 12 – December, 112 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: New Achievements in Modern Drama – Hsiao Lan

Paintings by Shanghai workers – Hu Chin

1975:

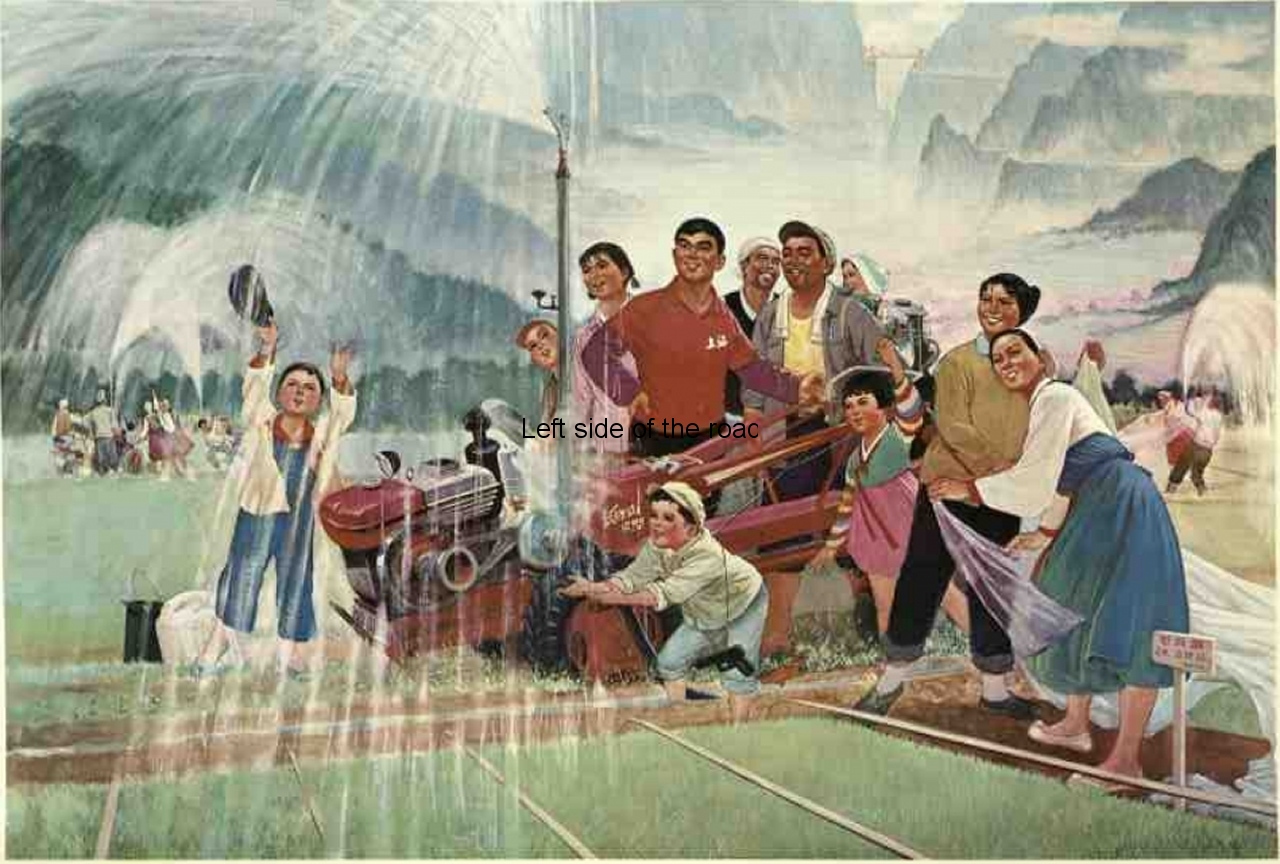

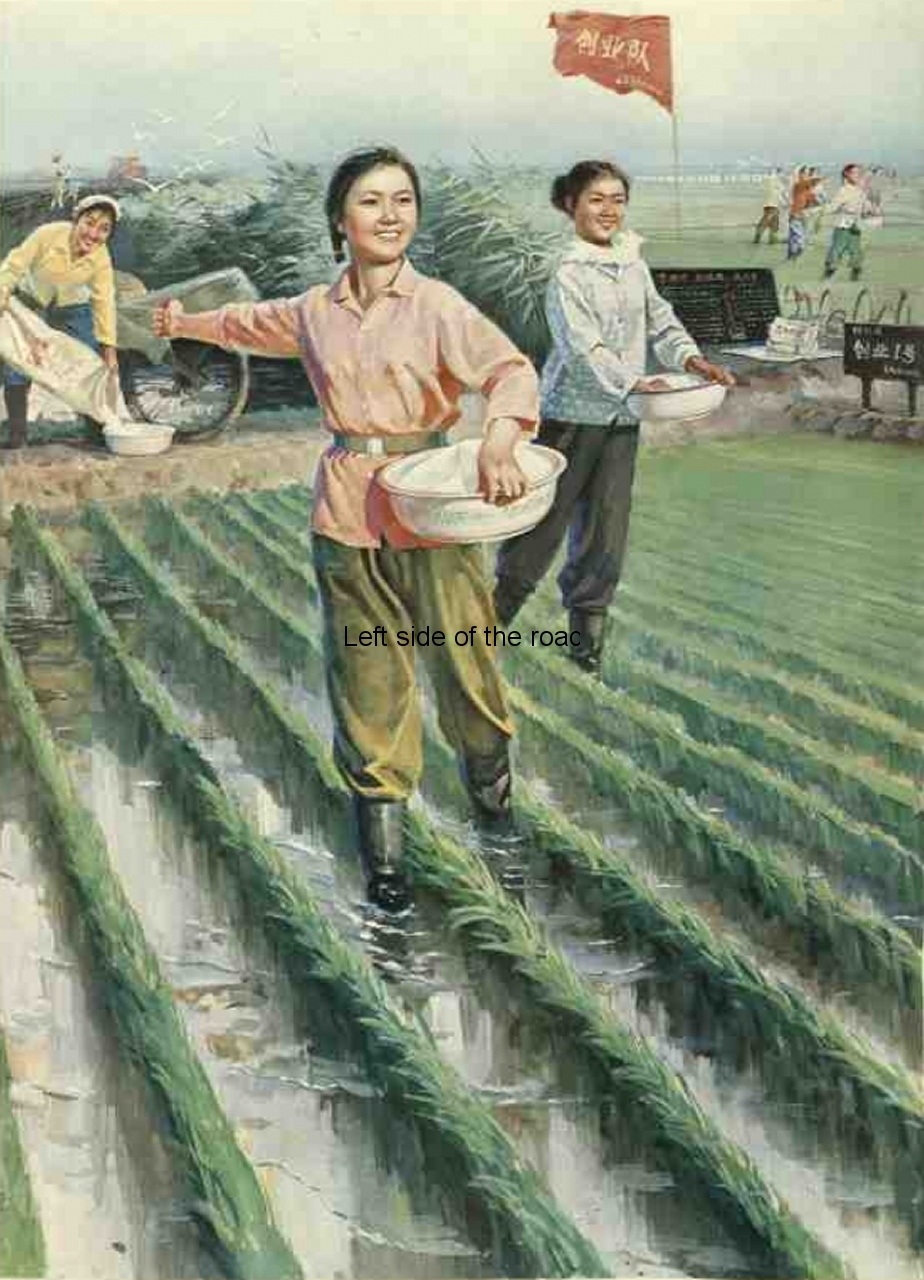

What a pleasure it is not to have to bend our backs while planting rice

- 1 – January, 122 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: National Art Exhibition – Wang Wu-sheng

The ‘Erh-hu’ and ‘Pi-pa – Wu Chou-kuang

- 2 – February, 140 pages. Contents include:

Sparkling Red Star (a film scenario) – Wang Yuan-chien and Lu Chu-kao

Notes on art: Adapting a novel for the screen – Lu Chu-kao

Creating the image of Winter Boy – Li Chun

As I acted Winter Boy I learned from him – Chu Hsin-yun

From a cameraman’s notebook – Tsai Chi-wei

- 3 – March, 138 pages. Contents include:

Pink Cloud Island (excerpts from the novel) – Chou Hsiao

Notes on art: Amateur worker-artists of Yangchuan – Pien Tsai

More rare finds from Han Tombs – Tsung Shu

- 4 – April, 134 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: The Creation of the ‘Red Silk Dance’ – Chin Ming

Some Popular Chinese wind instruments -Chou Tsung-han

Two oil paintings -Chi Cheng

- 5 – May, 106 pages. Contents include:

Lu Hsun‘s writings: From hundred plant garden to three flavour study

Notes on literature: On Reading ‘From hundred plant garden to three flavour study’ – Li Yun-ching

- 6 – June, 132 pages. Contents include:

Stories: The Sunlit Road

Tempered Steel

Notes on literature and art: New children’s songs from a Peking Primary School – Hsin Ping

New piano music – Lo Chiang

- 7 – July, 128 pages. Contents include:

The New Silk Road Across tie Skies (a poem) – Chang Yun-mei

Notes on literature and art: The struggle between the Confucians and Legalists in the History of Chinese Literature and Art – Chiang Tien

The Children’s Orchestra of Tachai – Yin Yuan

- 8 – August, 122 pages. Contents include:

A Young Hero (excerpt from a novel) – Shih Wen-chu

Notes on art: Chinese artists discuss their study of the ‘Yenan Talks’ by Chairman Mao

A new revolutionary dance drama – Hsin Wen-tung

The peasant songwriter Shih Chang-yuan – Yin Yuan

The Bright Road (excerpt from the novel) – Hao Jan

Notes on art: On the dance drama ‘Ode to the Yimeng Mountains’ – Tien Nui

Wuhu iron pictures – Lou Yang-shen

- 10 – October, 124 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: Introducing the Uighur Opera ‘The Red Lantern’ – Chumahung Suritan

Exhibition of children’s art in Shanghai – Kung Ping-tsu

Relics of the Long Match – Wen Hsuan

- 11 – November, 126 pages. Contents include:

Lu Hsun’s writings: The New-Year Sacrifice

On Lu Hsun’s Story ‘The New-Year Sacrifice’ -Chung Wen

Notes on literature and art: Songwriter of the Korean Nationality – Hsin Hua

Terracotta figures found near Chin Shih Huang’s tomb – Ni Ta and Chin Chun

- 12 – December, 114 pages. Contents include:

Criticism of ‘Water Margin’

The current criticism of ‘Water Margin’ – Chih Pien

What sort of novel is ‘Water Margin’? – Shih Chung

1976:

The most spectacular of landscapes

- 1 – January, 130 pages. Contents include:

Reminiscences of the Long March:

Crossing the Golden Sand River – Hsiao Ying-tang

Red Army men dear to the Yi People – Aerhmushsia

National minority poems and songs:

Sing, Skylark – Saifudin

Stride Forward – Saifadin

- 2 – February, 140 pages. Contents include:

Criticism of ‘Water Margin’:

Lu Hsun‘s Comments on the novel ‘Water Margin’ – Kao Yu-heng

Notes on art: The clay sculptures ‘Wrath of the Serfs’ – Kao Yuan

Our experience in sculpting ‘Wrath of the Serfs’

- 3 – March, 124 pages. Contents include:

Two poems – Mao Tse-tung

Chingkangshan revisited – to the tune of Shui Tiao Keh Tou

Two birds: A dialogue – to the tune of Nien Nu Chiao

New film: ‘The second spring’ – Tsung Shu

- 4 – April, 156 pages. Contents include:

Poems – Mao Tse-tung

Boulder Bay (a revolutionary modern Peking opera) – Ah Chien

Lu Hsun‘s writings: The other side of celebrating the recovery of Shanghai and

Nanking

- 5 – May, 132 pages. Contents include:

New film: Breaking with old ideas – Tien Shih

Notes on literature and art: On Chairman Mao’s recently published Poems

On the long poem ‘The song of our ideals’ – Wen Shao

Some new woodcuts – Yen Mei

- 6 – June, 138 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: Mass debate on Revolution in Literature and Art – Hsin Hua

A recently discovered poem by Lu Hsun – Chou Wen

A hundred flowers blossom in the field of dancing – Wen Sung

Juvenile art – Hsiao Mei

- 7 – July, 142 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: New developments in Chinese Acrobatics – Hsiao Fu

New group sculpture ‘Song of the Tachai Spirit’ – Wen Tso

What the Revolution in Literature and Art has taught me – Yang Chun-hsia

- 8 – August, 120 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: Continue to advance along Chairman Mao’s Line on Literature and Art – Yen Feng

New paintings by sSoldiers – Ko Tien

Some Taiping stone carvings – Chi Chen

Investigation of a chair (a modern revolutionary Peking opera) – Ah Chien

Notes on literature and art: The portrayal of the heroine in ‘Investigation of a Chair’ – Tsung Shu

‘The Undaunted’, a story by Chen Chung-shih

Poems from Hsiaochinchuang

- 10 – October, 132 pages. Contents include:

Spring Shoots (a film scenario)

Notes on literature and art: A song in praise of the Cultural Revolution – Shu Hsin

Pictures depicting the Cultural Revolution – Yen Mei

The entire issue was devoted to a commemoration of the life and work of Comrade Mao Tse-tung, who died in September 1976.

Includes some of his poems and many pictures taken throughout his life, both pre and post-Liberation.

1977:

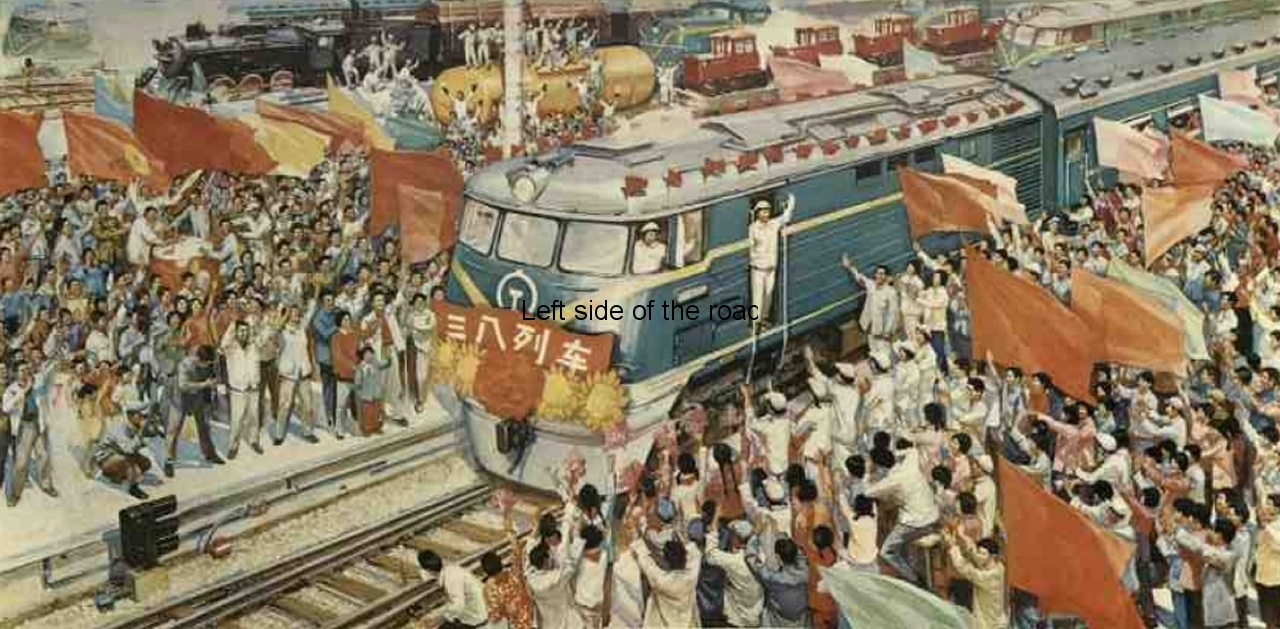

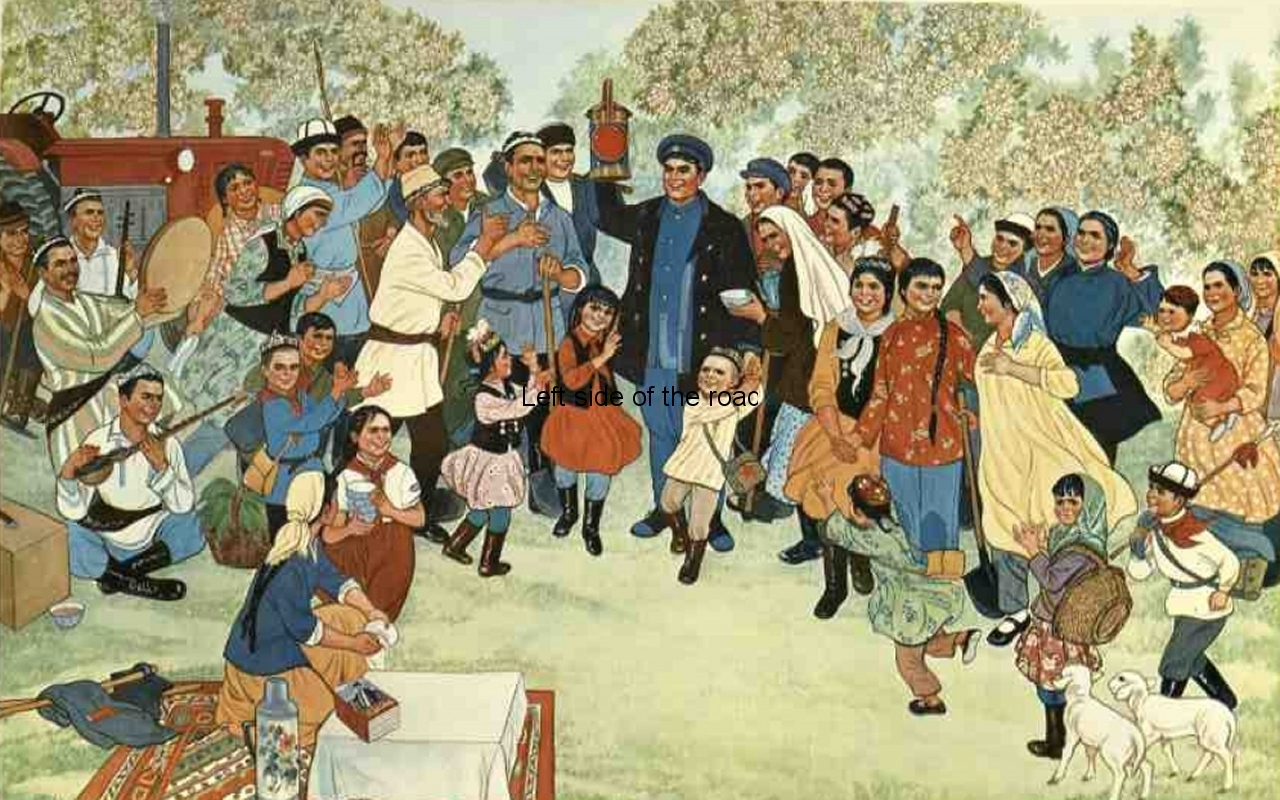

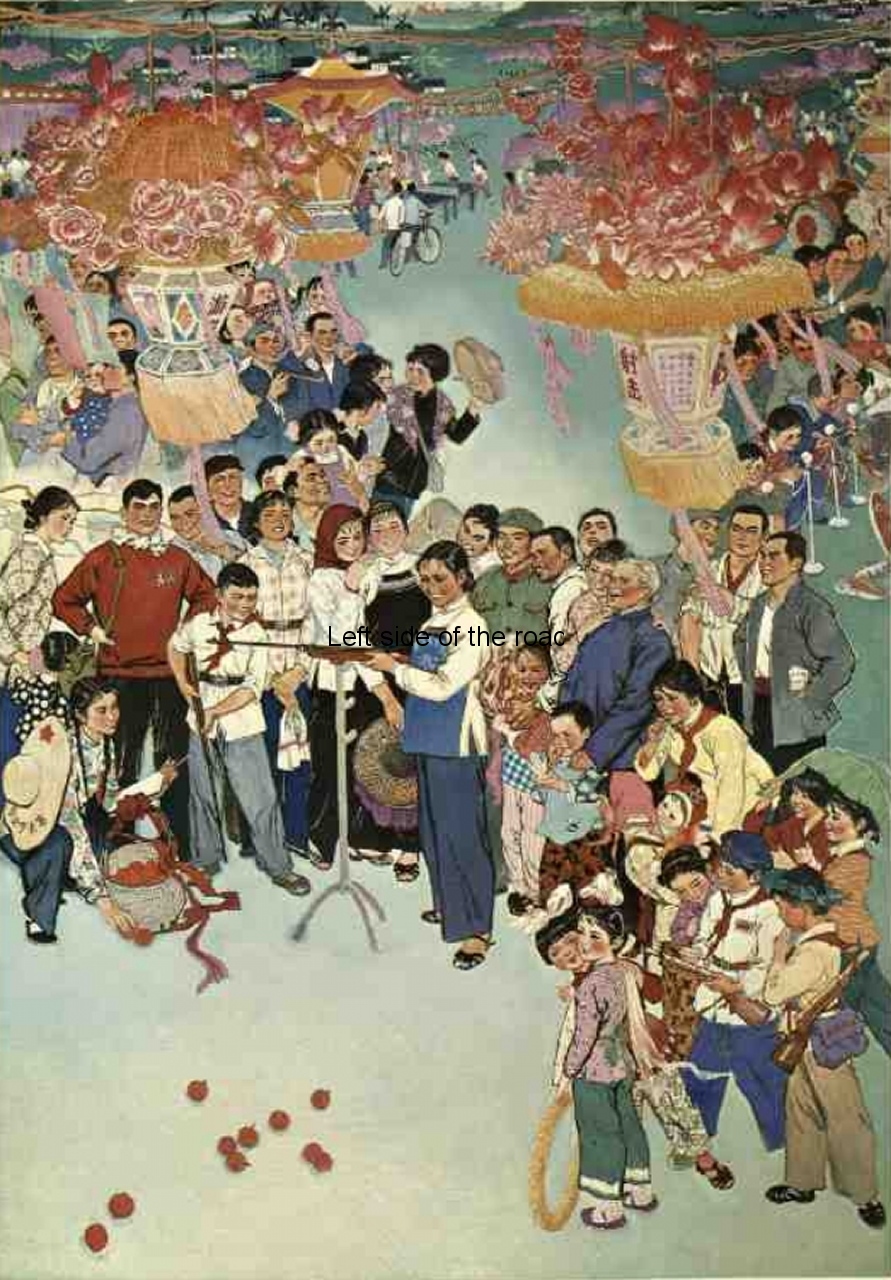

Great celebration of the victorious people

- 1 – January, 126 pages. Contents include:

‘The Pioneers’ [Part I], a film scenario about the Taching Oilfield, together with an 8-page selection of colour photographs from the film.

Poems

Smash the ‘Gang of Four‘ – Kuo Mo-jo

A grand festival for all revolutionaries – Kwang Wei-jan

Chairman Hua in his green army uniform – Yu Kuang-lieh

Chairman Hua leads us forward triumphantly – Shih Hsiang

- 2 – February, 140 pages. Contents include:

In memory of Chairman Mao: A Memorable Voyage – Hsin Chun-wen

Chairman Mao inspects Nanniwan – Tung Ting-heng

Chairman Mao shines like a red sun over the Earth – Li Shu-yi

Mass criticism: Chiang Ching, the ‘political pickpocket’ – an exposure of Chiang Ching

- 3 – March, 124 pages. Contents include:

In memory of Premier Chou:

Our beloved Premier Chou at Meiyuan New Village

Our beloved Premier Chou‘s three visits to Tachai

Mass criticism: The struggle around the film about Premier Chou En-lai

- 4 – April, 116 pages. Contents include:

Stories:

High in the Yimeng Mountains – Nieh Li-ko and Liang Nien

Sister Autumn -Chao Pao-chi

Revolutionary relics: A blanket in the Military Museum – Lin Chih-chang

- 5-6 – May-June, 116 pages. Contents include:

Lu Hsin’s writing: The True Story of Ah Q

Mass criticism: Chiang Ching‘s treachery in the criticism of ‘Water Margin’ – Chang Ya-erh

- 7 – July, 134 pages. Contents include:

Mass criticism: The ‘Gang of Four‘s’ revisionist line in literature and art – Hua Wen-ying

The truth behind the ‘Gang of Four‘s’ Criticism of the Confucians and glorification of the Legalists – Shih Kao

- 8 – August, 132 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: About the play ‘Maple Bay’ – Chi Ko

On reading Comrade Chu Teh‘s Poems – Hsieh Mien

Mass criticism: The ‘Gang of Four‘s’ reactionary approach to our cultural heritage – Liu Ming-chin

Notes on literature and art: Reading Lu Hsun‘s ‘Literature of a Revolutionary Period’ – Sun Yu-shih

An unforgettable night in Yenan – Huang Kang

My recollection of the production and first performances of ‘The White-haired Girl’ – Chang Keng

Two anthologies of poems by Taching workers – Wu Chao-chiang

- 10 – October, 136 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: In praise of the Taching Spirit – Yang Tung-mei

A grand display of Revolutionary Art – Li Shu-sheng and Shao Ta-chen

Woodcuts in China’s old Liberated areas – Hua Hsia

- 11 – November, 146 pages. Contents include:

Letter concerning the Study of ‘The Dream of the Red Chamber’ – Mao Tse-tung

Restudying Chairman Mao’s ‘Letter concerning the study of ‘The Dream of the Red Chamber’ – Li Hsi-fan

- 12 – December, 120 pages. Contents include:

Lu Hsun‘s writings: In memory of Wei Su-yuan

Lu Hsun’s friendship with Wei Su-yuan – Tu Yi-pai

1978:

Looking into the distance

- 1 – January, 129 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: Some paintings in the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall – Yuan Yun-fu

The Tung Fang Art Ensemble returns to the stage – Yu Chiang

Introducing classical Chinese literature: Myths and Legends of Ancient China – Hu Nien-yi

- Supplement: ‘Traditional Chinese Paintings’, colour photographs, 20 pages. Thesupplement to issue No. 1 contained 16 paintings in the Chinese ‘traditional’ style. By publishing these the capitalist state was declaring virtual war on the movement of Socialist Realism and the depiction of workers and peasants in their efforts to construct Socialism.

- 2 – February, 136 pages. Contents include:

Dr. Norman Bethune in China (a film scenario) – Chang Chun-hsiang and Chao To

Notes on art: Ashes of Revolutionaries Mingle Together – Ma Hai-teh

The Sculptures at The Chairman Mao Memorial Hall – Chi Shu

- 3 – March, 136 pages. Contents include:

Peking Opera: The making and staging of the Opera ‘Driven to Revolt’ – Chin Tzu-kuang

Driven to Revolt (two scenes from a Peking opera)

Introducing classical Chinese literature: The ‘Book of Songs’ – China’s earliest anthology of poetry – Hsu Kung-shih.

- 4 – April, 135 pages. Contents include:

Chairman Mao‘s Letter to Comrade Chen Yi Discussing Poetry – A forum on Chairman Mao’s Letter

Battling South of the Pass (excerpts from a novel) – Yao Hsueh-yin

- 5 – May, 144 pages. Contents include:

Lu Hsun‘s writings: Village Opera

On Lu Hsun’s ‘Village Opera’ – Fang Ming

Notes on art: Introducing ‘Sketches of the Long Match’ – Chi Feng-ho

Restoration of the Yunkang Caves – Yin Wen-tsu

- 6 – June, 126 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: An introduction to ‘Li Tzu-cheng – Prince Valiant’ – Mao Tun

The ‘Gang of Four‘s’ attack on progressive literature and art – Chieh Cheng

The Weifang New-Year woodblock prints – Chang Chin-keng

- 7 – July, 126 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: On reading poems written by Premier Chou in his youth – Chao Pu-chu

Some works from the Arts and Crafts Exhibition – Lien Hsiao-chun

Odsor, a Mongolian Nationality writer – Hsiao Chou

Introducing a classical painting: Chan Tzu-chien’s painting ‘Spring Outing’ – Shu Hua

- 8 – August, 138 pages. Contents include:

Lu Hsun’s writings:

Preface to ‘A collection of woodcuts by amateur Artists’

Letter to Li Hua

Letter to Lai Shao-chi

Lu Hsun and Chinese woodcuts – Li Hua

Cultural event: Prominent cultural figures meet in Peking

Introducing classical Chinese literature: Han Dynasty verse essays and allads – Hu Nien-yi

- 10 – October, 146 pages. Contents include:

Conference of Writers and Artists: My heart felt wishes (a message) – Kuo Mo-jo

Strive to bring about the flourishing of literature and art (an abridged speech) – Huang Chen

The Literary Scene: News of some veteran writers

- 11 – November, 138 pages. Contents include:

Notes on lieterature and art: A hundred flowers in bloom again – Tu Ho

‘The Red Lantern Society’ – a new Peking Opera – An Kuei

Batik in China – Teng Feng-chien

Introducing a classical painting: Wu Wei and his painting ‘Fishermen’ – Shu Hua.

- 12 – December, 134 pages. Contents include:

Notes on literature and art: On creative writing – Mao Tun

Translations of foreign literature – Wei Wen

Ornamental plate designs by Li Ping-fan – Yu Ming-chuan

1979:

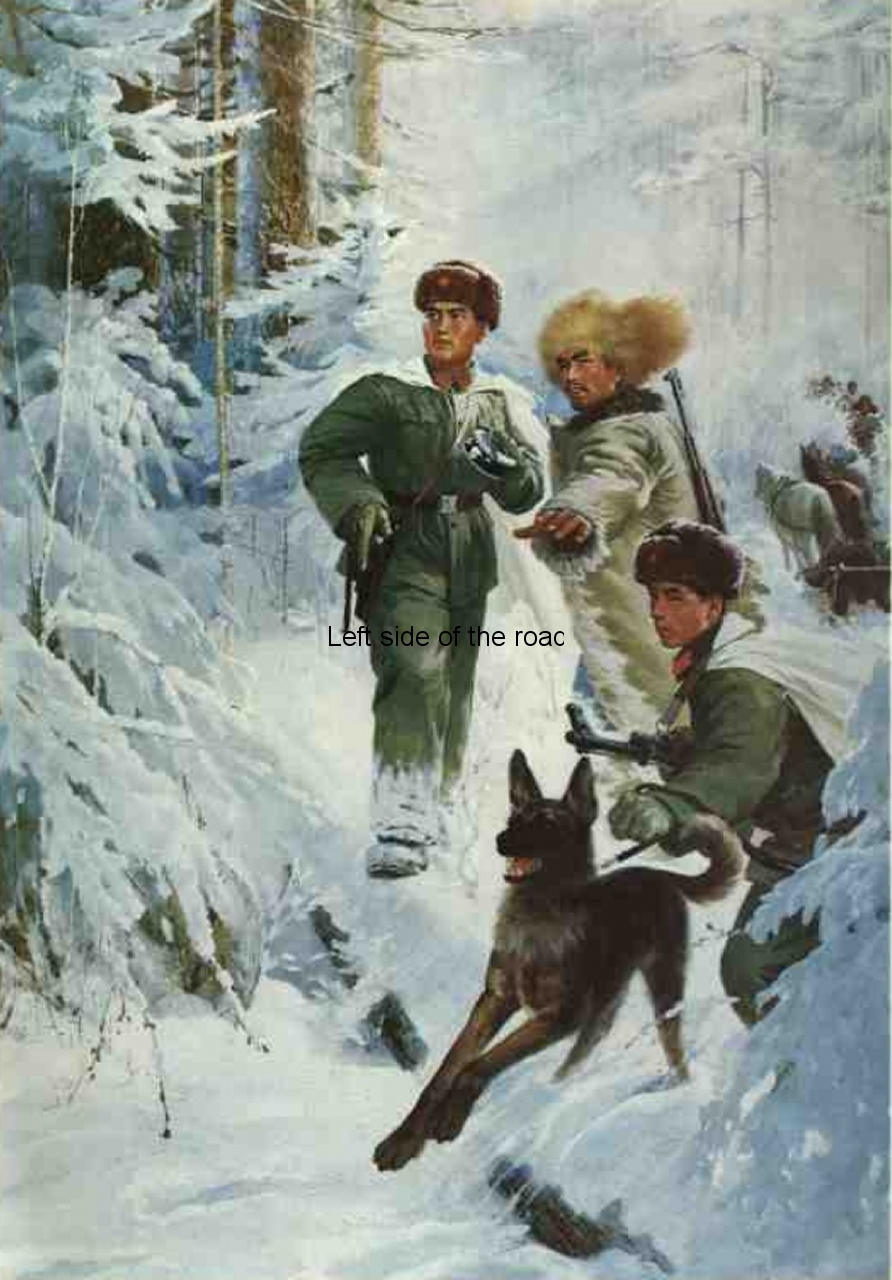

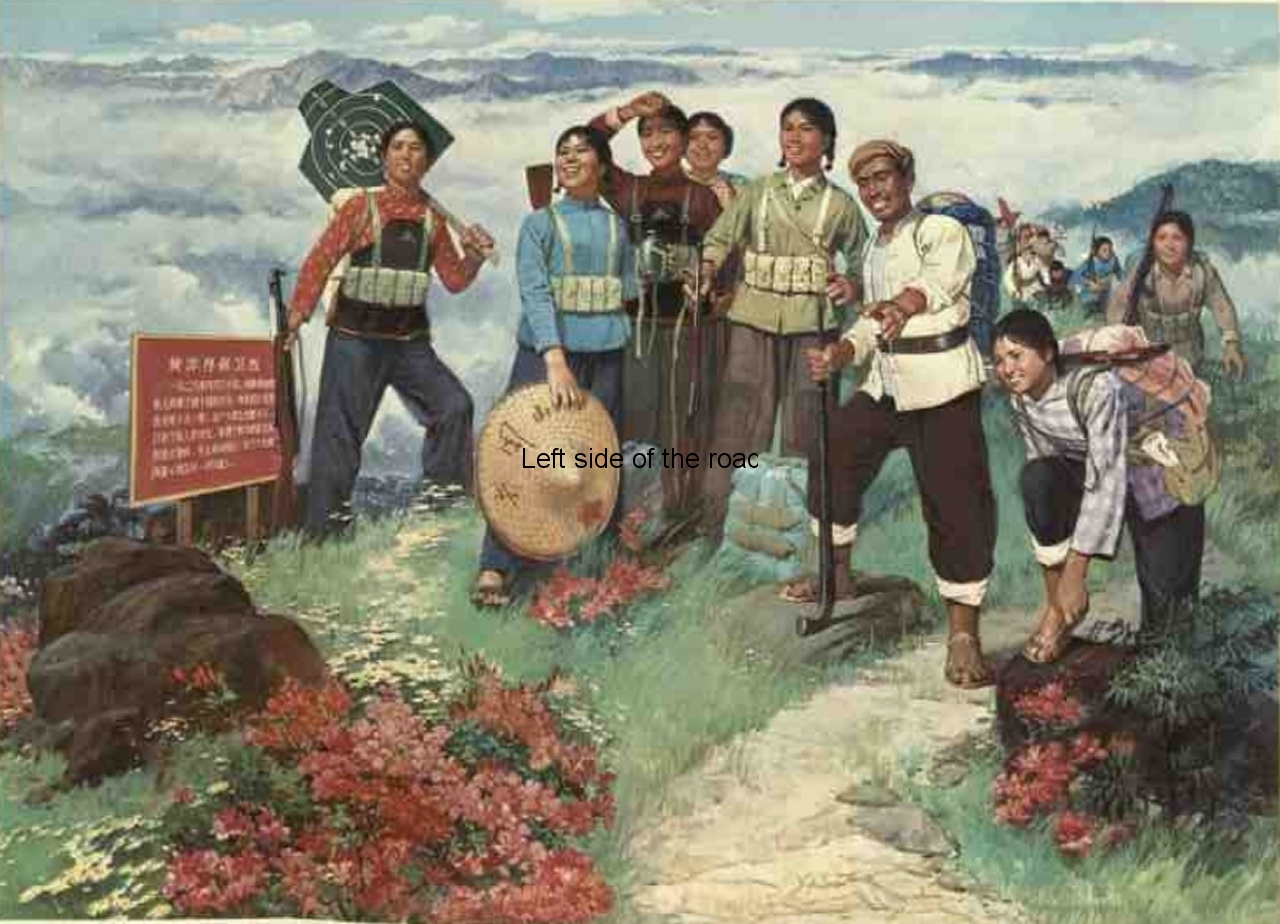

Bravely fighting the enemy

Notes on literature and art:

Yangliuching New-Year pictures – Shao Wen-chin

New productions in the Peking Drama Theatre – Feng Txz

Make the past serve the present and foreign culture serve China – Tu Ho

The role of Critical Realism in European Literature – Liu Ming-chiu

- 2 – February. (Not yet available)

- 3 – March, 133 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: New ornamental porcelain produced by Cheng Ko – Pu Wei-chin

‘At the Crossroad Inn’ – Liu Hu-sheng

Introducing a classical painting: Chou Ying and his painting ‘Peach Dream-land’ – Chang Jung-jung

- 4 – April, 140 pages. Contents include:

When all sounds are hushed (a four-act play) – Zong Fuxian

Lu Xun’s writings: Postscript to ‘The Grave’

A Correspondence on Themes for Short Stories

- 5 – May, 138 pages. Contents include:

Introducing classical Chinese literature: Tang Dynasty Poets (1) – Qiao Xianzong and Wu Gengshun

Poems of Li Bai

Poems of Du Fu

- 6 – June, 142 pages. Content includes:

Zhou Enlai on Questions Related to Art and Literature

Memories of Premier Zhou at the 1961 Film Conference – Huang Zongying

- 7 – July, 130 pages. Contents include:

Cultural exchange: Boston Symphony Orchestra in China -Yan Liangkun

Introducing a classical Chinese painting: Silk Fan Painting ‘Returning Home After Drinking’ – Zhang Rongrong

- 8 – August, 150 pages. Contents include:

Exhibition of Huang Yongyu’s paintingsRare cultural relics excavatedIntroducing a classical painting: Tang Yin and his painting ‘Four Beauties’ – Tian Xiu

Introducing a classical Chinese painting: ‘The Broken Balustrade’ – Li Song

Introducing classical Chinese literature: The Classicist Movement in the Tang Dynasty – Zhang Xihou

Prose writings of Han Yu

Prose writings of Liu Zongyuan

- 10 – October, 140 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: Sword Dance – Liu Enbo

Introducing a classical painting: Hua Yan and his painting ‘A lodge amid pine trees’ – Qi Liang

- 11 – November. (Not yet available)

- 12 – December, 151 pages. Contents include:

Notes on art: Some Chinese Cartoon Films – Yang Shuxin

Introducing a classical painting: ‘The Connoisseur’s Studio’ by .Wen Zhengming – Tian Xiu

1980:

Deep in thought

- 1 – January (Not yet available)

- 2 – February (Not yet available)

- 3 – March (Not yet available)

- 4 – April (Not yet available)

- 5 – May, 132 pages. Contents include:

Introducing classical Chinese literature: Yuan-Dynasty Drama and San-Qu Songs -Lu Weifen

San-Qu Songs of the Yuan Dynasty

Introducing a classical Chinese painting: Liang Kai’s ‘Eight eminent monks’ – Xia Yuchen

- 6 – June (Not yet available)

- 7 – July, 140 pages. Contents include:

The cinema: ‘The Effendi’, a new cartoon film – Ge Baoquan

- 8 – August (Not yet available)

- 9 – September, 142 pages. Contents include:

Introducing classical Chinese literature: Fiction in the Qing Dynasty – Shi Changlu

Selections from the ‘Strange tales of Liaozhu’ – Pu Songling

Five old Chinese fables

- 9 – September (Not yet available)

- 10 – October, 144 pages. Contents include:

In memory of Agnes Smedley: Lu Xun and Agnes Smedley – Jan and Steve MacKinnon

Reminiscences of Lu Xun – Agnes Smedley

The Ashington miners’ paintings – Chang Pin

1981:

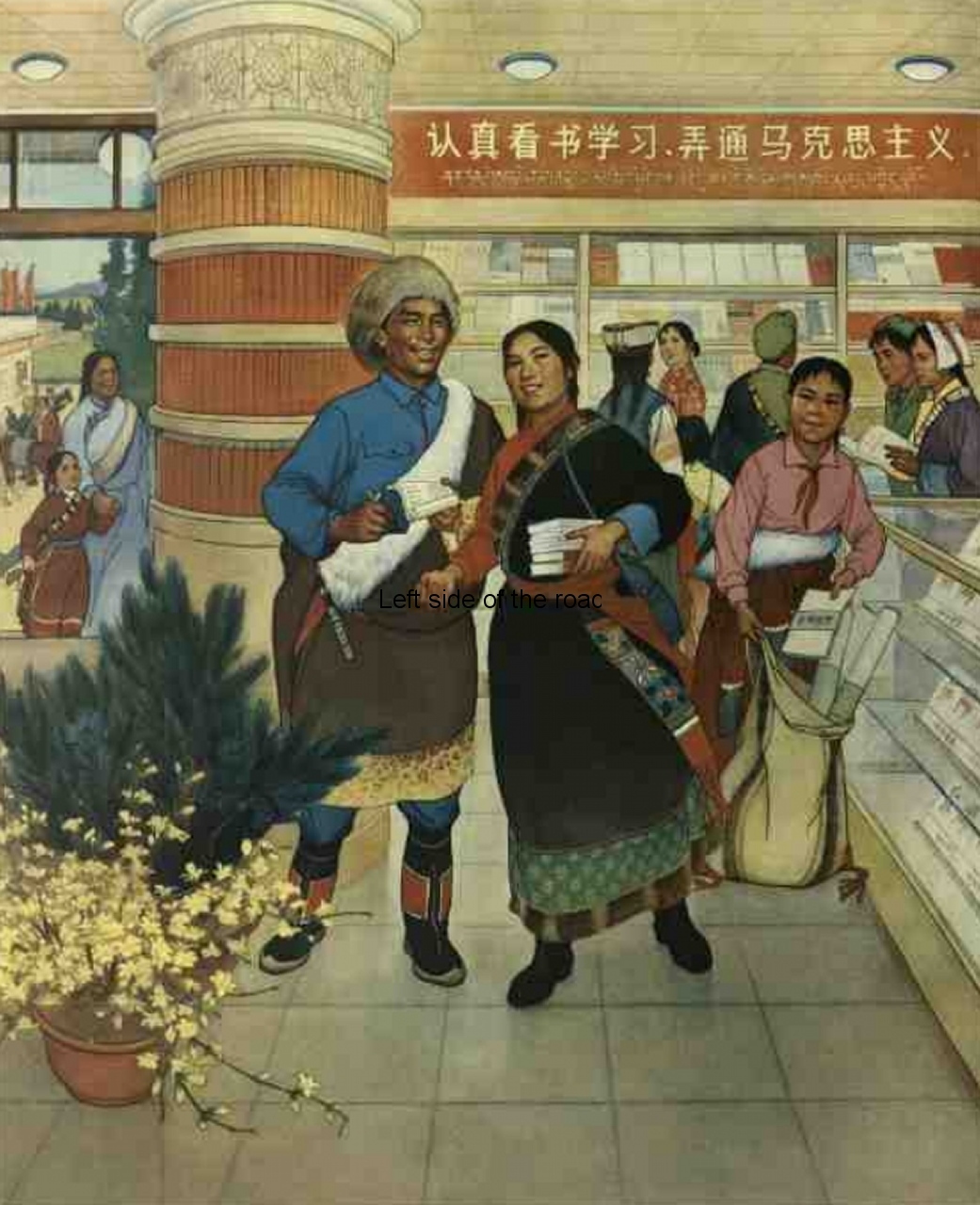

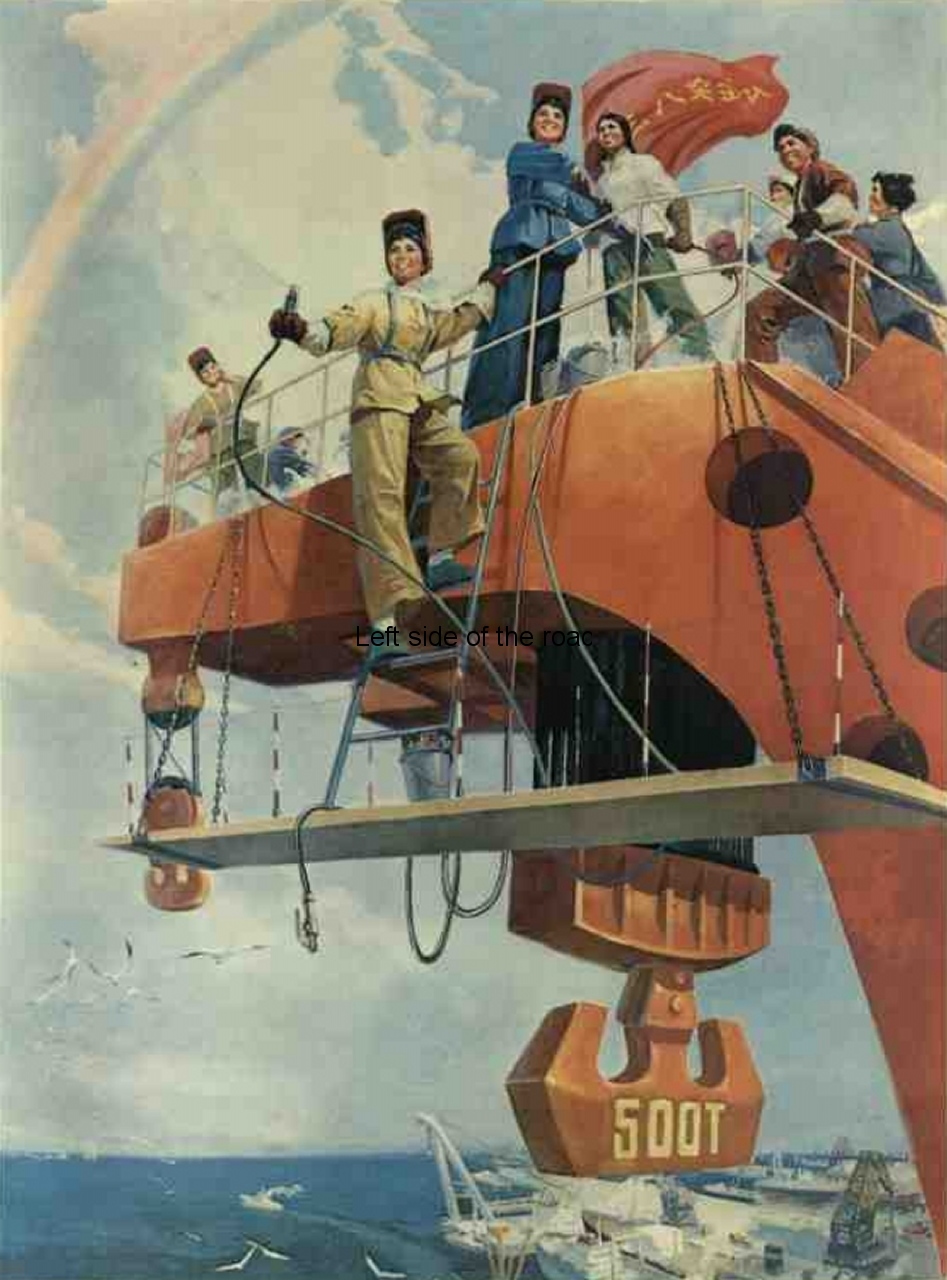

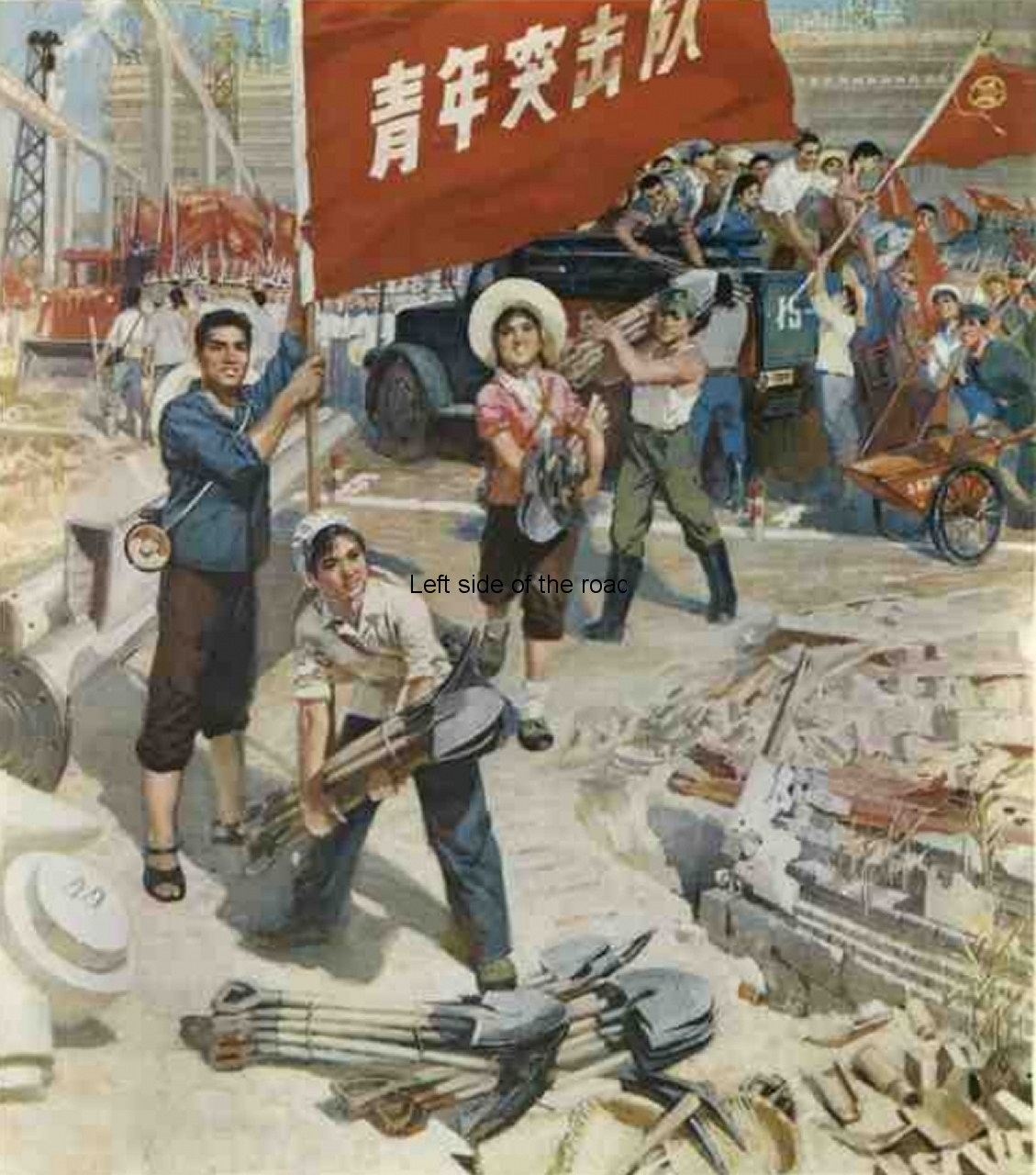

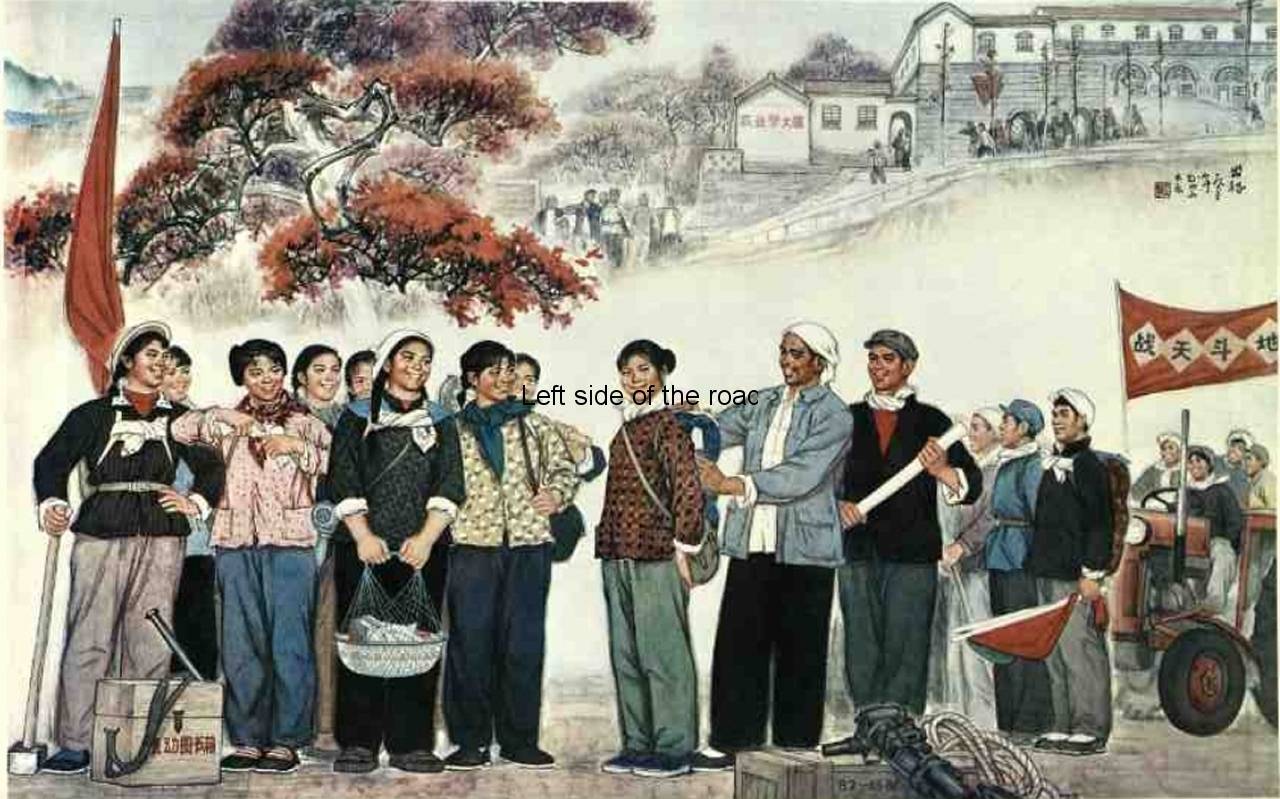

Carry out the Four Modernisations of the Fatherland

- 1 – January (Not yet available)

- 2 – February (Not yet available)

- 3 – March (Not yet available)

- 4 – April (Not yet available)

- 5 – May, 148 pages. Contents include:

Book Review: Researches into Tang-Dynasty Poets – Ji Qin

Introducing a Classical Painting ‘Wang Xizhi inscribes fans’ – Shan Guolin

- 6 – June, 147 pages. Contents include:

Introducing Classical Chinese Literature: A Visit to Yandang Mountain -Xu Xiake

On Taihua Mountain

The Travel Notes of Xu Xiake -Wu Yingshou

- 7 – July (Not yet available)

- 8 – August (Not yet available)

- 9 – September (Not yet available)

- 10 – October (Not yet available)

- 11 – November (Not yet available)

- 12 – December (Not yet available)

More on China …..