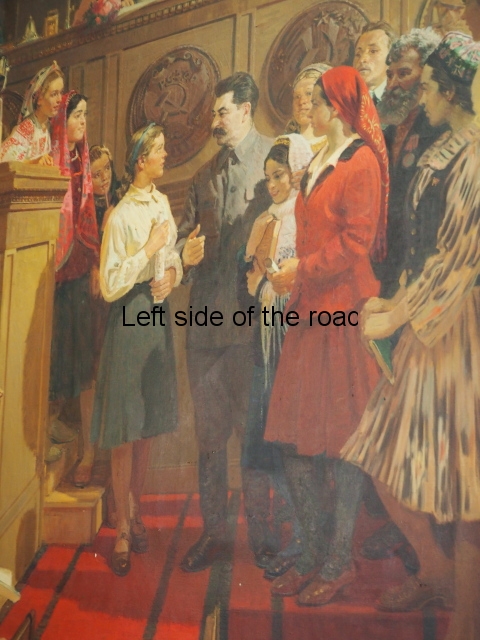

A Collective Farm Festival

More on the USSR

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told

Soviet Society

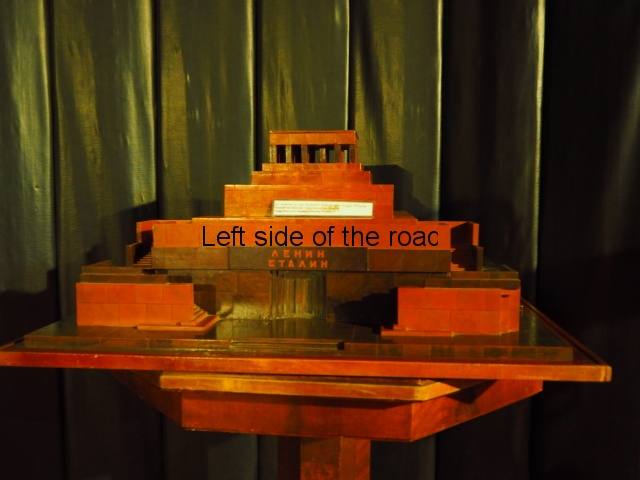

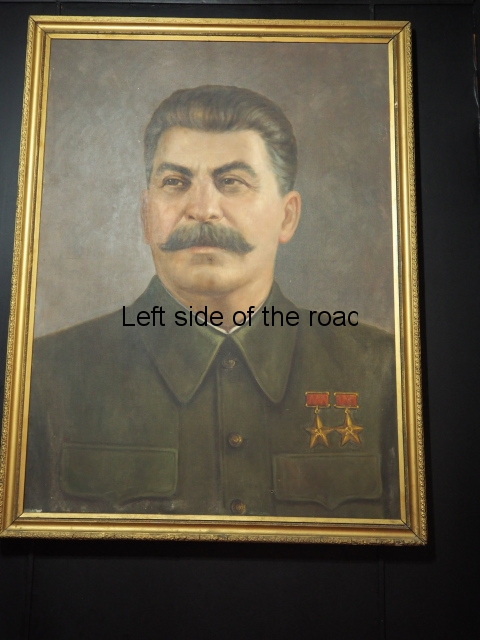

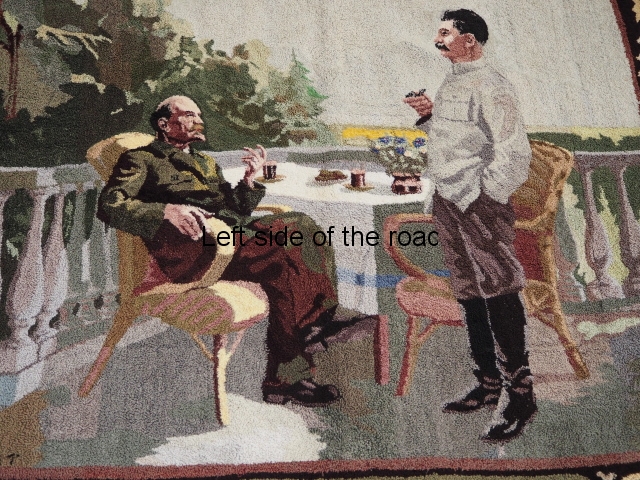

A view of different aspects of life when the people of the USSR were attempting to construct a new society in a hostile world of capitalism and imperialism – which used every opportunity to undermine the task of the revolutionary workers and peasants in the country that covered one-sixth of the world’s land mass.

The Marriage Laws of Soviet Russia, complete text of first code of laws of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic dealing with Civil Status and Domestic Relations, Marriage, the Family and Guardianship, Soviet Russia Pamphlets No. 2, The Russian Soviet Government Bureua, New York, 1921, 49 pages.

Red Star in Samarkand, Anna Louise Strong, Coward McCann, New York, 1929, 329 pages.

The Soviet Five-year Plan and its effect on world trade, HR Knickerbocker, Bodley Head, London, 1931, 245 pages.

From the First to the Second Five-Year Plan, a Symposium, J Stalin, V Molotov, L Kaganovich, K Voroshilov and others, Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers in the USSR, Moscow, 1933, 490 pages.

In Place of Profit, social incentives in the Soviet Union, Harry F Ward, Scibner’s Sons, New York, 1933, 460 pages.

Foreign trade in the USSR, JD Yanson, The New Soviet Library, Gollanz, London, 1934, 175 pages.

Buryat-Mongolia, International Publishers, New York, 1936, 56 pages.

Soviet Russia and Religion, Corliss Lamont, International pamphlets No 49, International Publishers, New York, 1936, 23 pages.

The Reconstruction of Moscow, Lev Perchik, Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers in the USSR, Moscow. 1936, 72 pages.

Soviet Communism, a new civilisation, Volume One, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Scibners, New York, 1936, 528 pages.

Soviet Communism, a new civilisation, Volume Two, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Scibners, New York, 1936, 645 pages.

Handbook on the Soviet Trade Unions, for workers’ delegations, edited by A Lozovsky, Cooperative Publishing Company of Foreign Workers in the USSR, Moscow, 1937, 144 pages.

Soviet Democracy, Pat Sloan, Left Book Club, Victor Gollanz, London, 1937, 288 pages.

Socialised Medicine in the Soviet Union, Henry E Sigerist, Left Book Club, Victor Gollanz, London, 1937, 397 pages.

The position of women in the USSR, GN Serebrennikov, Victor Gollanz, London, 1937, 117 pages.

A Visit to Russia, Report of Durham Miners Association, 1937, 56 pages.

From Tsardom to the Stalin Constitution, WP and Zelda Cpates, Aleen and Unwin, london, 1938, 332 pages.

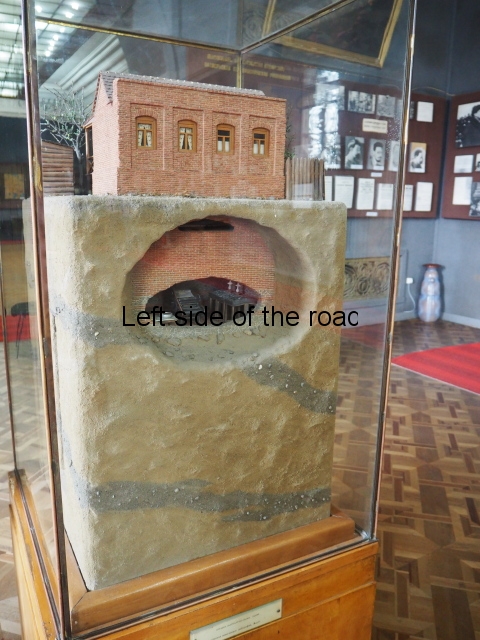

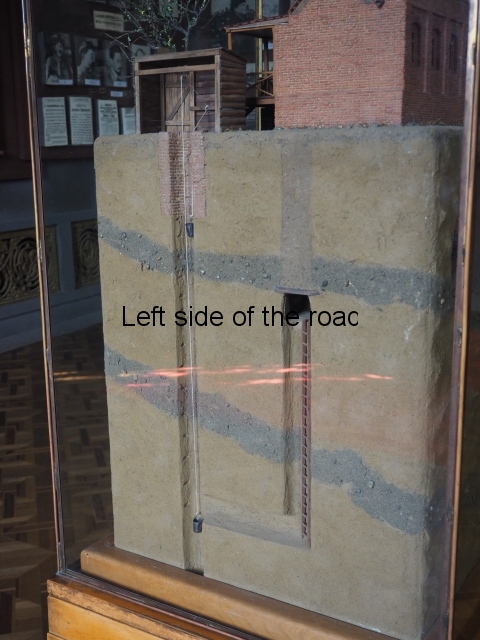

The Moscow Subway, Y Abakumov, FLPH, Moscow, 1939, 24 pages.

Universities in the USSR, ULF Pamphlet No 7, University Labour Federation, London, 1939, 20 pages.

The State Farms of the USSR, P Lobanov, People’s Commissar of State Farms of the USSR and Member of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, FLPH, Moscow, 1939, 32 pages.

Soviet Students, S Kaftanov, Chairman of the Committee on Higher Education of the Council of Peoples’ Commissars of the USSR, FLPH, Moscow, 1939, 32 pages.

Sport In the USSR, A Starostin, FLPH, Moscow, 1939, 31 pages. (Apologies, bad scan. Pages out of sequence.)

State Farms of the USSR, P Lobanov, People’s Commissar of State Farms of the USSR, FLPH, 1939, 32 pages.

Light on Moscow, DN Pritt, Penguin, London, 1940, 223 pages.

USSR speaks for itself, No 1, Industry, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1941, 95 pages.

USSR speaks for itself, No 2, Agriculture and Transport, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1941, 104 pages.

USSR Speaks for itself, No 3, Democracy in Practice, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1941, 104 pages.

How the Soviet State is run, Pat Sloan, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1941, 128 pages.

Marriage and The Family in the USSR, D Erde, Soviet Booklets, No. 2, Soviet War News, London, 1942, p16.

The Russians are people, Anna Louise Strong, Cobbett Publishing, London, 1943, 202 pages.

Peoples of the USSR, Anna Louise Strong, Macmillan, New York, 1944, 246 pages.

The truth about Soviet Union, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, with an essay on the Webbs by Bernard Shaw, Longmans, London, 1944, 79 pages.

Soviet Farmers, Anna Louise Strong, Pocket Library of the USSR, National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, New York?, n.d., 1944?, 47 pages.

Soviet Local Government, the administration of village and city explained, rates and taxes, elections, gas, water, electricity and other municipal services, Don Brown, Russia Today, London, 1945, 24 pages. (Apologies, bad scan, pages out of order.)

USSR, her life and her people, Maurice Dobb, University of London Press, 1945, 139 pages.

The Pattern of Soviet Power, Edgar Snow, Random House, New York, 1945, 219 pages.

These are the Russians, Richard Lauterback, Harper, New York, 1945, 368 pages.

Introducing the USSR, Beatrice King, Pitman, London, 1946, 112 pages.

Soviet Democracy, Harry F. Ward, Soviet Russia Today, New York, 1947, 48 pages.

Soviet Communism, A New Civilization, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Longman’s, London, 1947, 1007 pages.

The Right-Wing Social-Democrats Today, O Kuusinen, FLPH, Moscow, 1948, 35 pages.

Industry in the USSR, E Lokshin, FLPH, Moscow, 1948, 170 pages.

The Soviet way of life, an examination, Maurice Lovell, Methuen, London, 1948, 213 pages.

The Law of the Soviet State, Andrei Yanuaryevich Vyshinskiy, Macmillan Company, New York, 1948, 749 pages.

Man and Plan in Soviet Economy, Andrew Rothstein, digitised version, first published in London 1948, 145 pages.

Soviet Economic Development since 1917, Maurice Dobb, Routledge Kegan Paul, London, 1948, 487 pages.

Industry in the USSR, E Lokshin, FLPH, Moscow, 1948, 170 pages.

Dialectical Materialism and Historical Science, VP Volgin, np., 1949, 5 pages.

Across the map of the USSR, N Mikhailov, FLPH, Moscow, 1949, 344 pages.

Fulfilment of the USSR State Plan for 1949, communique of the Central Statistical Administrration of the USSR Council of Ministers, Soviet News, London, 1950, 22 pages.

The role of the State in the Socialist Transformation of the economy of the USSR, KV Ostroviyanov, FLPH, Moscow, 1950, 11 pages.

The Soviet Union Today, a scientist’s impressions, SM Manton, with an foreword by Lord Boyd-Orr, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1952, 133 pages.

Questions and answers on Property (Public and Private) in the USSR, Soviet News, London, 1954, 24 pages.

Soviet Law and Soviet Society, ethical foundations of the Soviet structure, mechanism of the planned economy, duties and rights of peasants and workers, rulers and toilers, the family and the state, Soviet justice, national minorities and their autonomy, the People’s Democracies and the Soviet pattern for a united world, George Guins, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, 1954, 457 pages.

The Soviet Regime, Communism in Practice, WW Kulski, Syracuse University Press, New York, 1954, 807 pages.

Education in the USSR, ASYFA, n.d., n.p., 12 pages. (Apologies, bad scan, pages all out of sequence.)

Questions and answers on Working Conditions in Soviet Industry, Soviet News, London, 1954, 30 pages.

Engineering progress in the USSR, A Zvorykin, FLPH, Moscow, 1955, 80 pages.

Problems and Achievements of Soviet Historical Science, abridged from the brief survey presented to the International Congress in Rome in September 1955, AL Sidorov, Society for Cultural Relations with the USSR, London, 1955, 13 pages.

Soviet civilization, Corliss Lamont, Philosophical Library, New York, 1955, 447 pages.

Political economy – a textbook issued by the Institute of Economics of the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.S.R, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1957, 623 pages.

Soviet Economic Development since 1917, Maurice Dobb, International Publishers, New York, 1966 (reprint of 1948 original), 515 pages.

Jews in the Soviet Union – Fact versus Fiction, British Soviet Friendship Society, London, 1971, 4 pages.

Fraud, famine and fascism, the Ukrainian genocide myth from Hitler to Harvard, Douglas Tottle, Progress Books, Toronto, 1987, 167 pages.

Bourgeois nations and Socialist nations, V. Kozlov, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 64 pages.

Constitution (Fundamental Law) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, (Stalin Constitution), As Amended and Added to at the First and Second Sessions of the Supreme Soviet of the U.S.S.R., Third Convocation, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2022, 158 pages.

Democracy and Dictatorship in the Soviet Union & Soviet farmers, Anna Louise Strong, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 115 pages.

Great construction works of Communism and the remaking of nature, V.A. Kovda, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 81 pages.

On the Soviet Union, Paul Robeson, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2022, 54 pages.

Religion in the USSR, E Yaroslavsky, President of the League of Militant Atheists of the Soviet Union, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2022, 101 pages.

Socialism and the individual, M.D. Kammari, November 8th Publishing House, Toronto, 2022, 106 pages.

The Soviet White Paper on the North Atlantic Pact, translation of the full text of the Statement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the USSR, published in the Moscow Izvestia, January 29, 1949, November 8th Publishing House, Toronto, 2022, 49 pages.

The Stalin Era, Anna Louise Strong, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 176 pages.

Women in the Land of Socialism, Nina Popova, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 194 pages.

Anton Semenovich Makarenko

….was a Ukrainian and Soviet educator, social worker and writer, became the most influential educational theorist in the Soviet Union.

Lectures to Parents, National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, 1961, 30 pages. These texts are lectures that were given by Makarenko over the radio in 1937. They were published in the Literaturnaia Gazetta after he died in 1939, and also in the Collected Works of Makarenko, Vol. 4, 1951.

A Book for Parents, FLPH, Moscow, 1954, 410 pages.

Workers control and socialist democracy, The Soviet experience, Carmen Sirianni, Verso, London, 1982, 437 pages.

Road to Life, Part 1, n.p., n.d., 282 pages.

Road to Life, an epic of education, volume 2, FLPH, Moscow, 1955, 179 pages. Online Version: A. S. Makarenko Reference Archive (marxists.org) 2002.

Anton Semyonovitch Makarenko, an analysis of his educational ideas in the context of Soviet Society, Frederic Lilge, University of California, Berkeley, 1958, 52 pages.

More on the USSR

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told