Gori Great Patriotic War Museum – 01

More on the Republic of Georgia

The Great Patriotic War Museum and War memorial – Gori

The Museum

This is quite a small museum and considering the huge numbers of people – especially during the tourist season – who go to Gori for the Stalin Museum (only a couple of hundred metres up the road) doesn’t get many visitors at all.

For many of those who do go there it might appear somewhat underwhelming as it doesn’t contain a lot of artefacts. However, I think that’s the ‘problem’ of the visitor not the museum – but also a ‘problem’ of which I myself am guilty.

War museums in the west – or certainly in the UK – are devoted to the instruments of war, the weapons that have been used through the ages as technology makes the task of killing someone ‘easier’ and more sophisticated. Yes, there will be exhibitions, normally ‘special’ ones that complement/supplement the permanent display, that place a greater emphasis on those who were fighting or were caught up in the conflict but the norm is to display what does the killing.

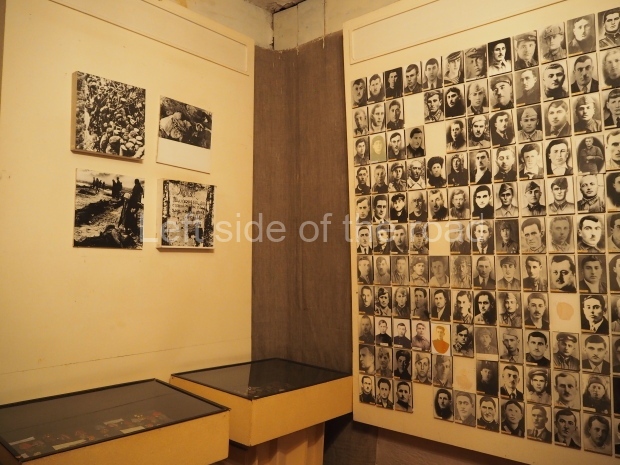

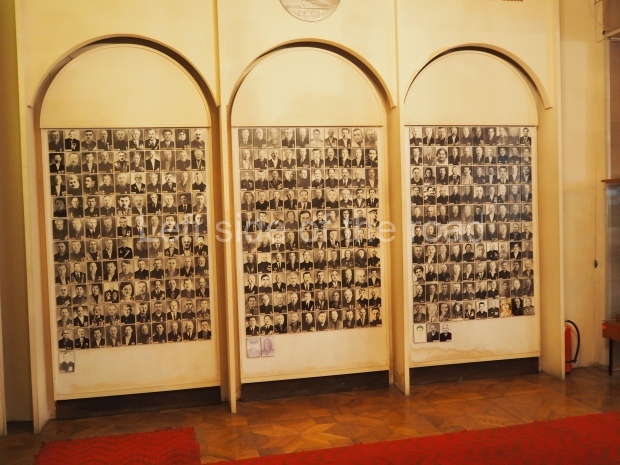

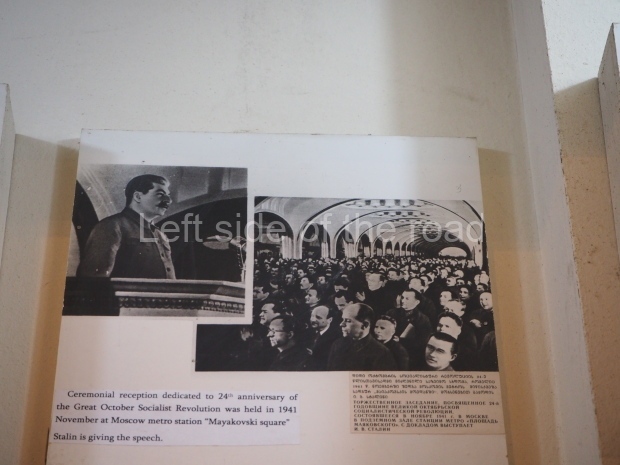

I think I’ve come to understand – and it took the visit to a number of museums in various part of what was the Soviet Union – that Soviet museums of the Great Patriotic War were primarily dedicated to those who fought and died. The museums were more like memorials to the dead than celebrations of what was used to kill them.

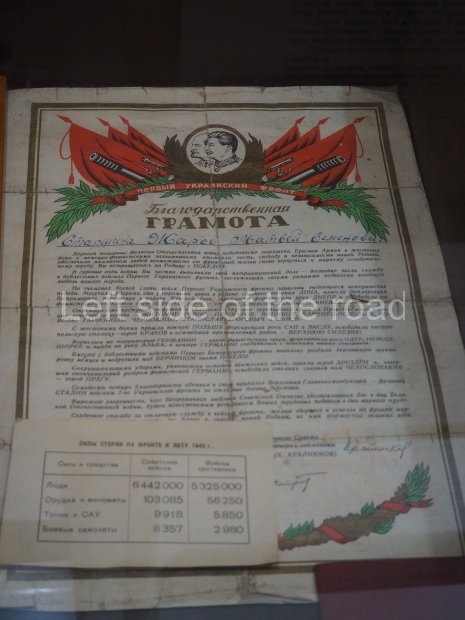

Although the museum in Gori is small this is even more evident in a couple of the larger museums I have visited recently – the first being the Museum of the Great Patriotic War in Moscow and the second the Museum to the Battle of Stalingrad in Stalingrad/Volgograd. Both those museums have military equipment on show but the vast majority of the items on display are much more personal, items that the soldiers and civilians carried as well as many photographs of those who fought and died.

At the heart of both those museums is a virtual shrine to those who gave their lives for the Soviet Motherland to which visiting groups of school children, military personnel – as well as many other Russian visitors – treat as a sort of pilgrimage to pay homage and thanks to those who died in the fight against Nazism. Even though the Soviet Union collapsed many years ago the Russian people still understand that the Great Patriotic War was an ‘existential’ (a word that has probably become overused in recent times) struggle for the country. Defeat wouldn’t have just meant losing the war, it would have resulted in the end of the Russian people as a nation.

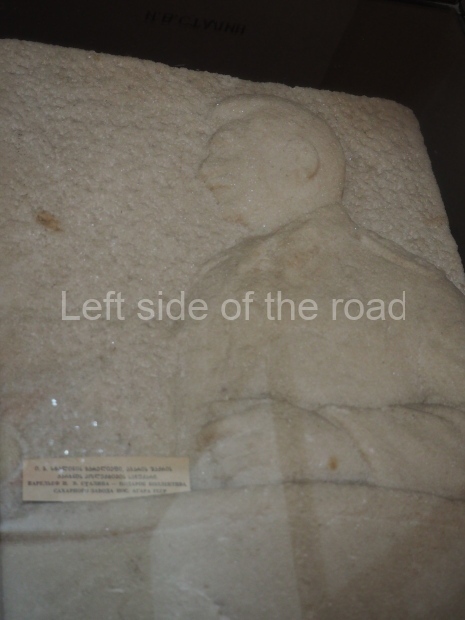

And the museum in Gori mirrors that but on a much smaller scale. When it comes to exhibits there more in the way of photographs, of scenes from the various battle fronts but also of Georgians (and, I must assume, those from Gori and the surrounding area) who died in the war. Although there was no fighting on the territory of Georgia as such around 350,000 Georgians lost their lives on other fronts and in other battles against the Nazis. In this museum some of those are remembered with their photographs displayed in the corner of the museum.

Gori Great Patriotic War Museum – 02

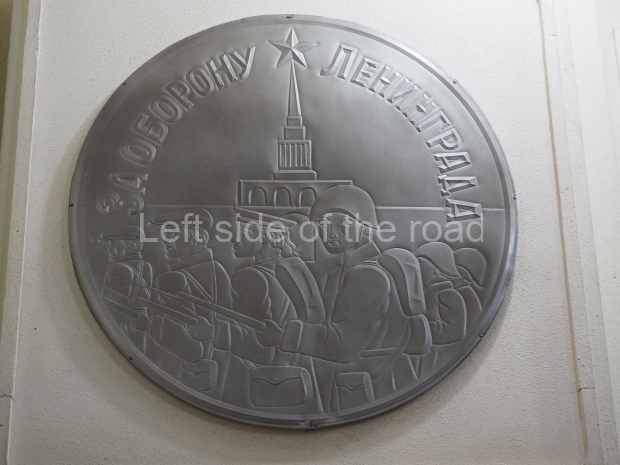

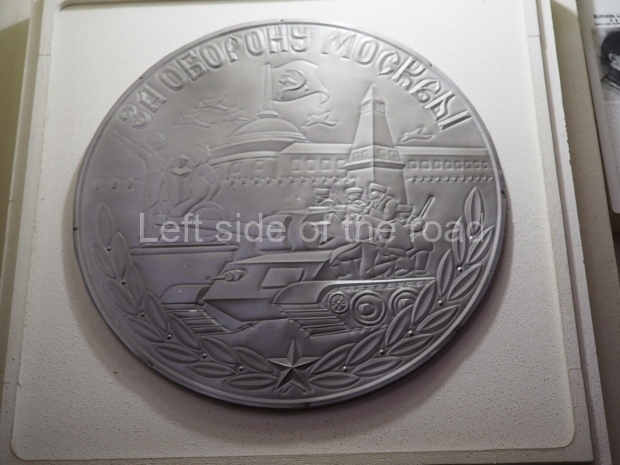

There are, however, other items of interest for a visitor. These include;

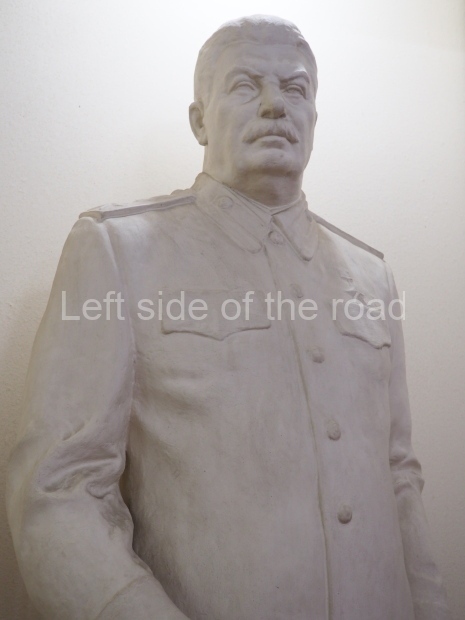

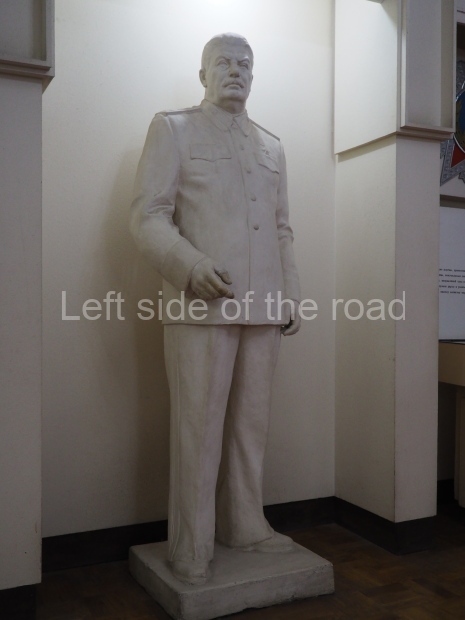

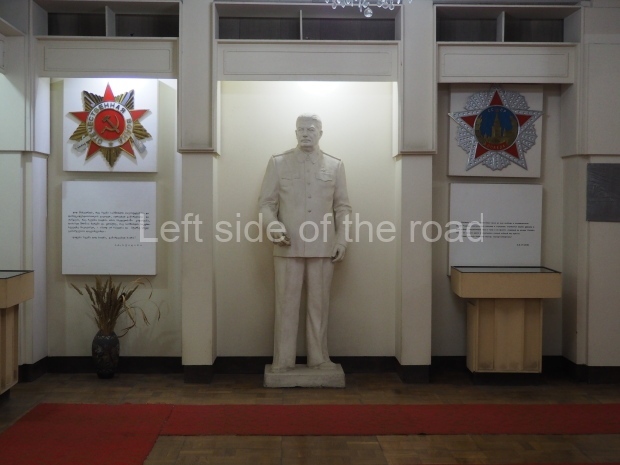

- a full length statue of Joseph Vassarionovich Djughashvili (Joseph Stalin) standing at the bottom on the single room which is the museum. Not the best of likenesses but one to add to those searching for his statues in Gori, complementing those in a near-by park and the railway station. (Both those a more accurate likeness, I think.);

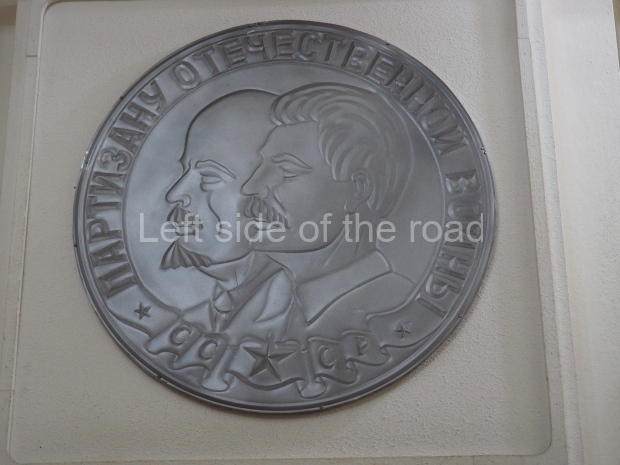

- a number of interesting banners from different regiments and battalions, some with images of VI Lenin and/or JV Stalin. Some are not in the best of condition but not surprising considering the ferocity of the battles;

Gori Great Patriotic War Museum – 03

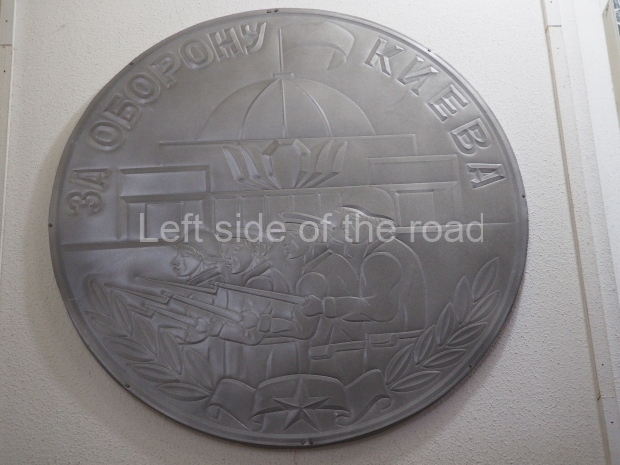

- a collection of Nazi insignia, in display cases on the floor – emulating the fate of the Nazi banners thrown at the feet of Stalin, and in front of the Lenin Mausoleum, in Red Square on the first Victory Day in 1945;

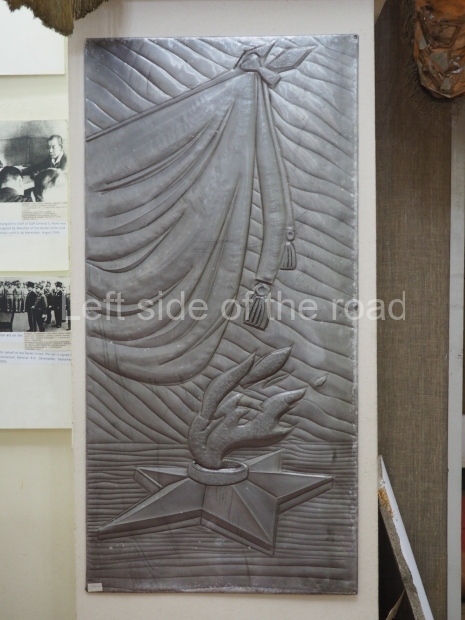

- a small statue depicting homage to the Red Flag.

The War Memorial

Great Patriotic War Memorial – Gori

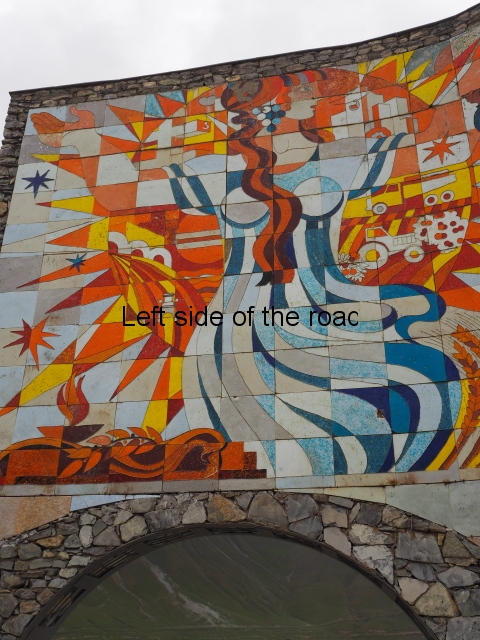

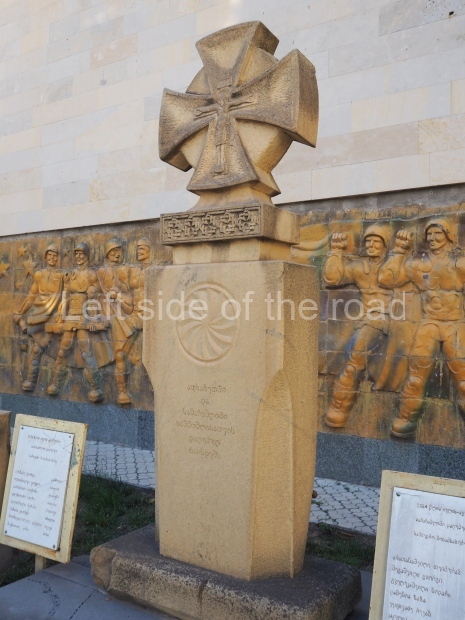

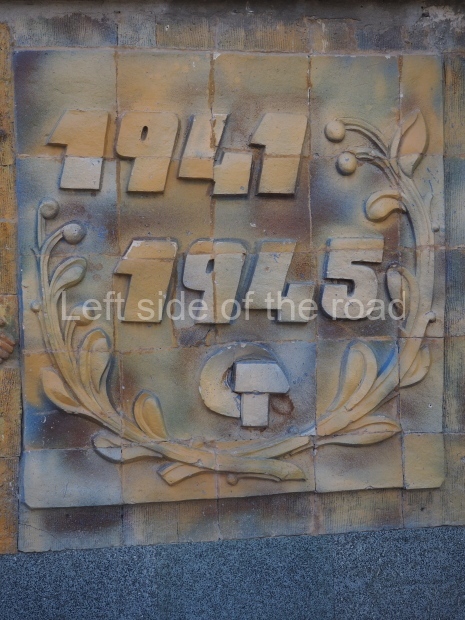

Gori’s War Memorial, to the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945, is located in Hero’s Square – which is the small garden in front of the main entrance to the museum.

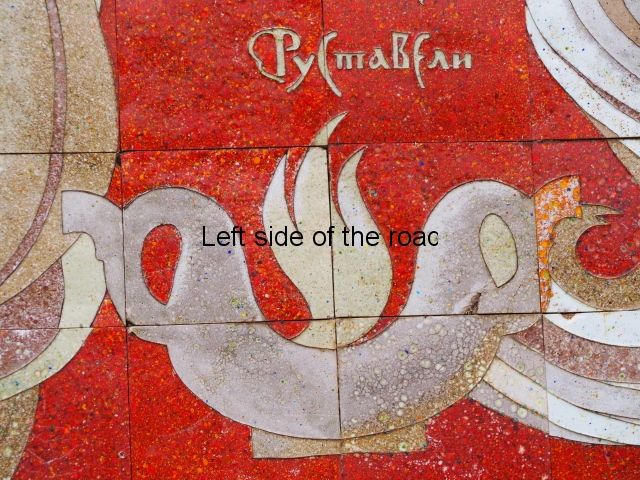

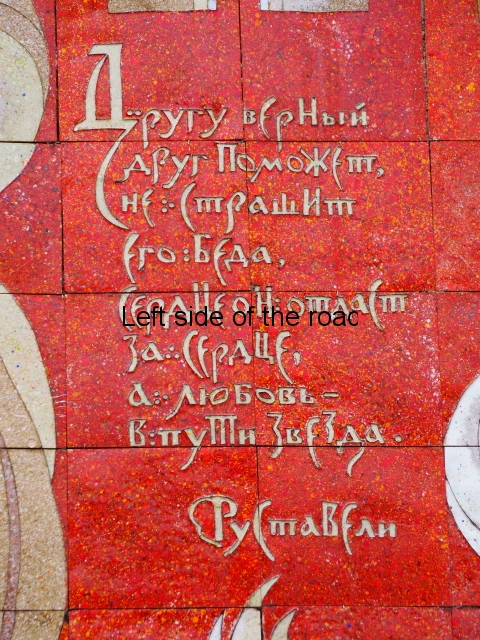

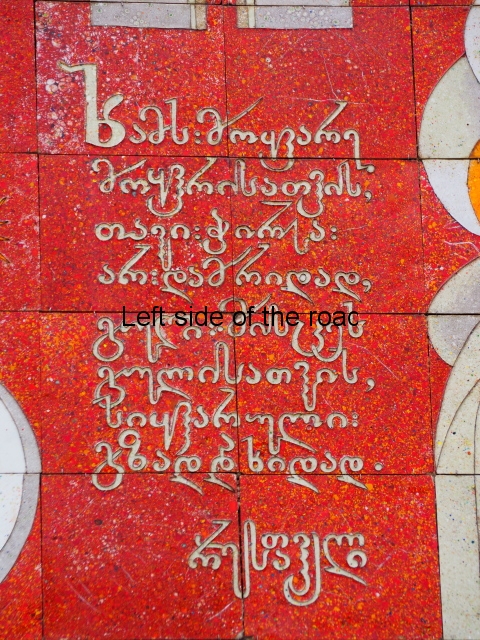

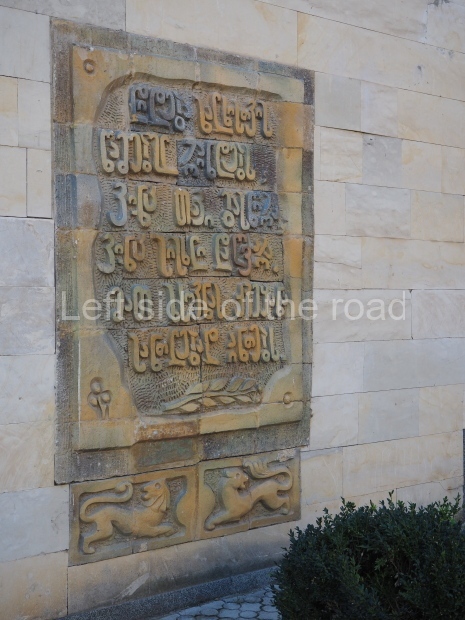

The memorial begins just to the right of the museum entrance. Here there’s a plaque, in Georgian, with an inscription which quotes part of the poem by the Georgian poet Galaktion Tabidze – ‘Let the Banners Wave on High’ (დროშები ჩქარა):

‘დიდება ხალხისთვის წამებულ რაინდებს,

ვინც თავი გასწირა, ვინც სისხლი დაღვარა.

მათ ხსოვნას სამშობლო სანთლებად აინთებს’

‘Glory to those with souls devoid of fear,

Who for the people’s cause did bravely die…

Their names shine bright like torches in the night…’

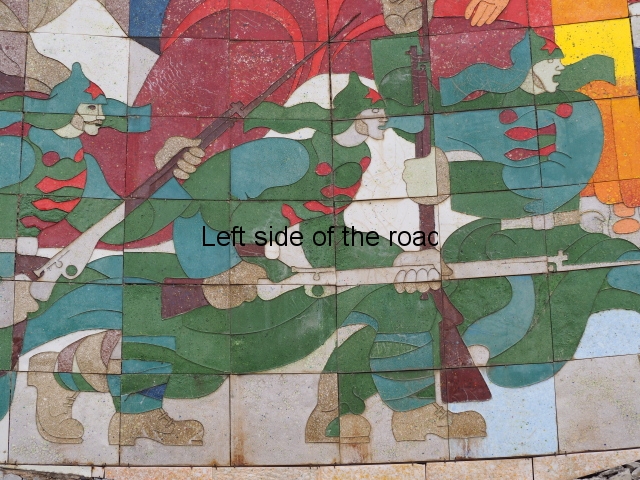

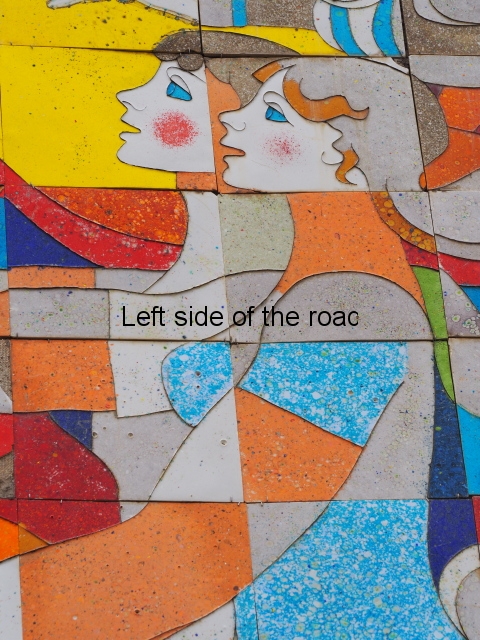

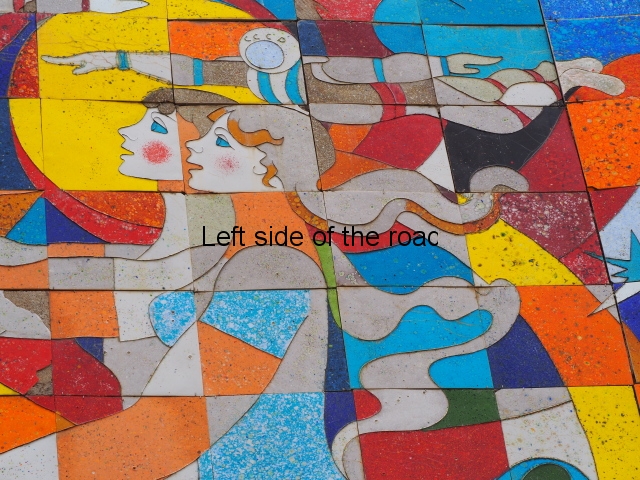

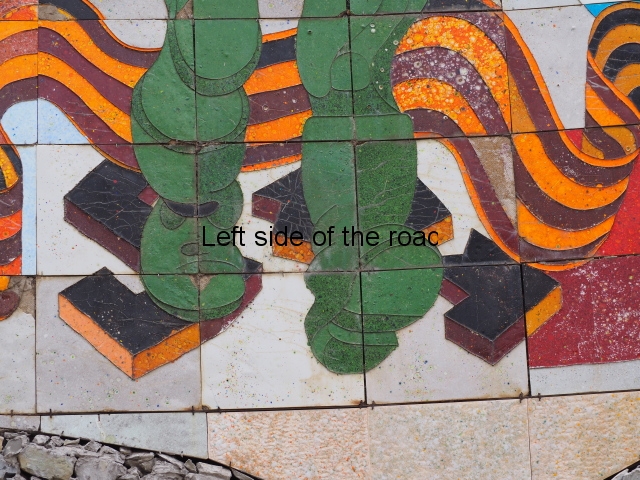

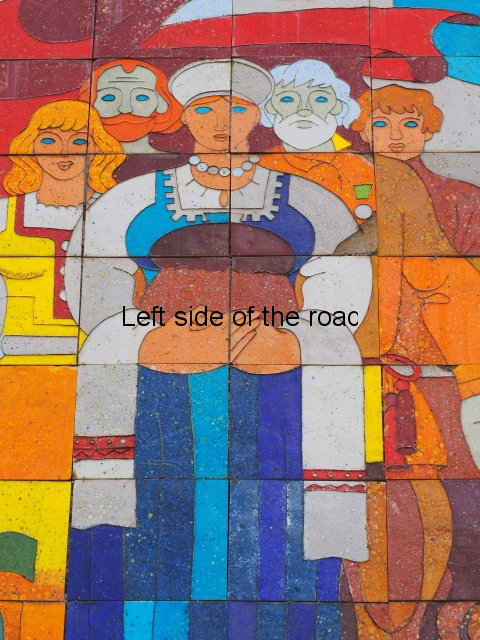

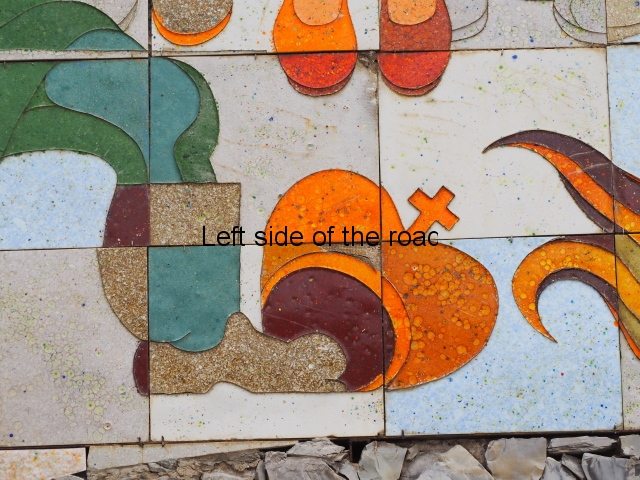

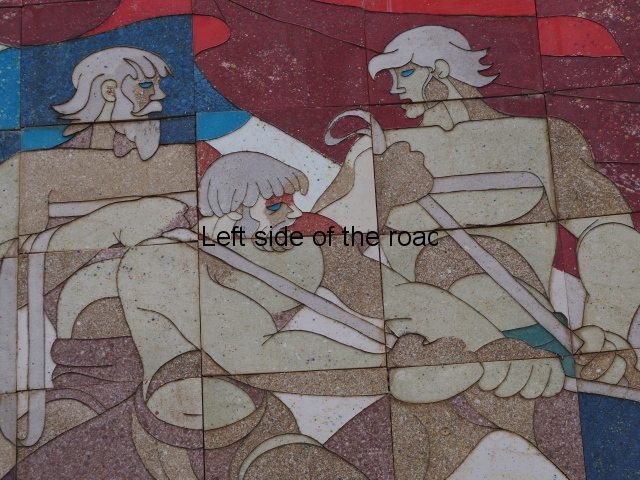

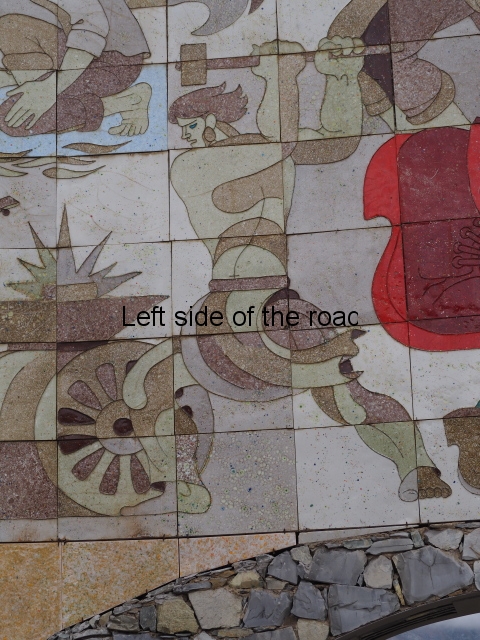

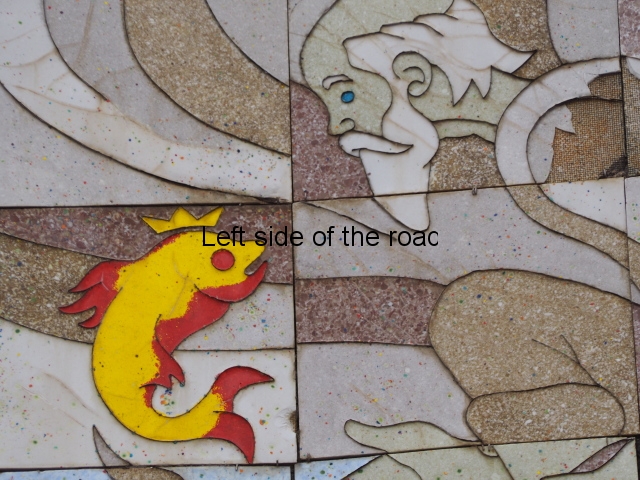

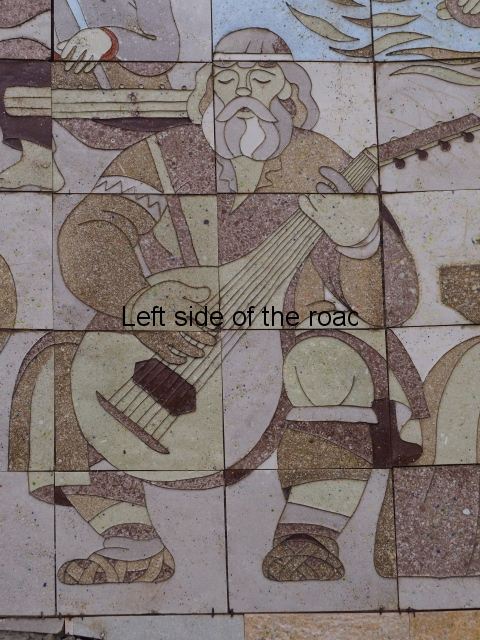

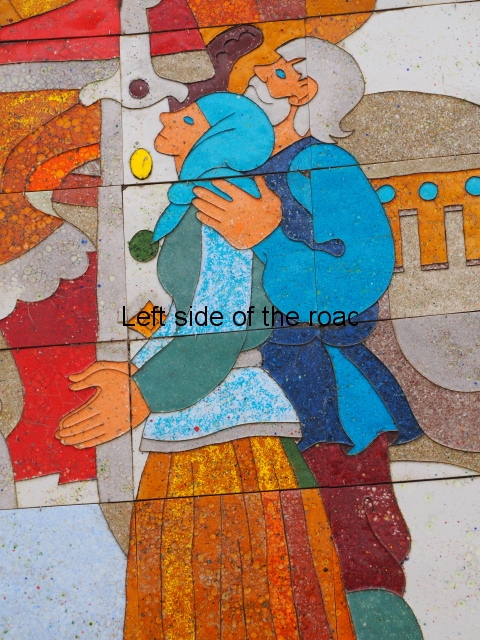

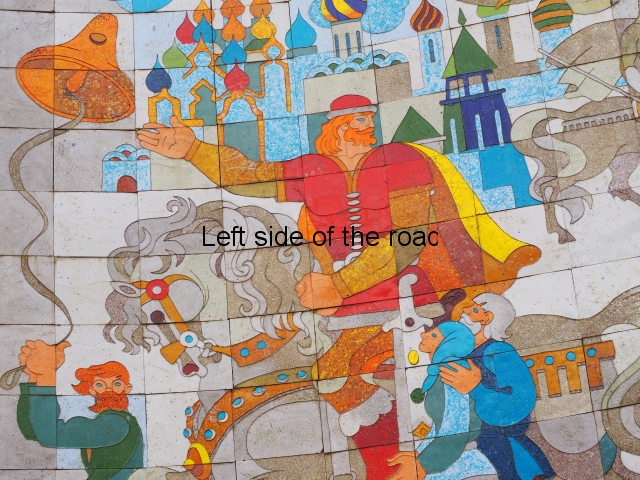

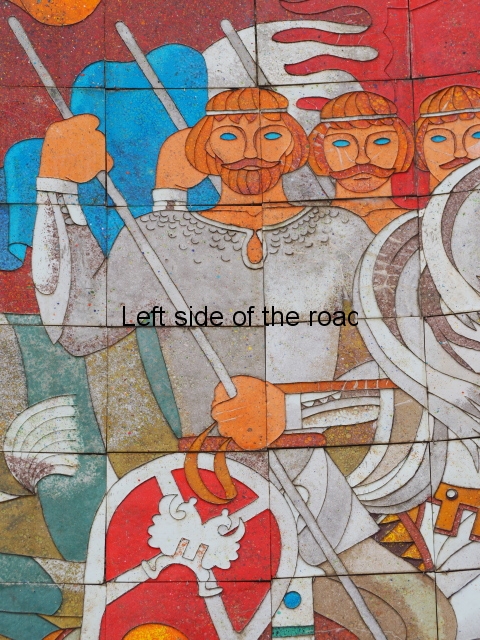

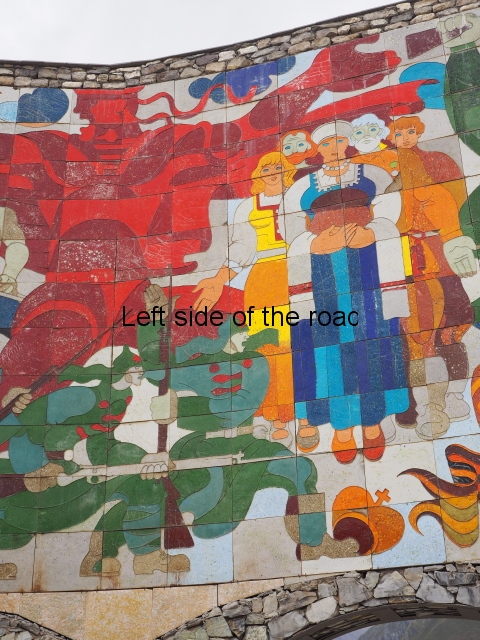

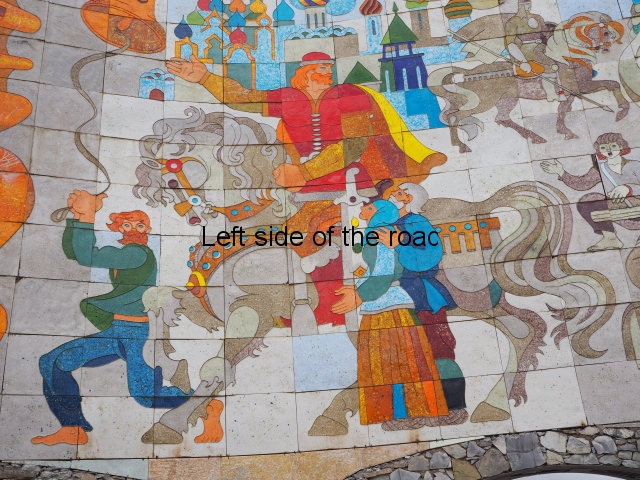

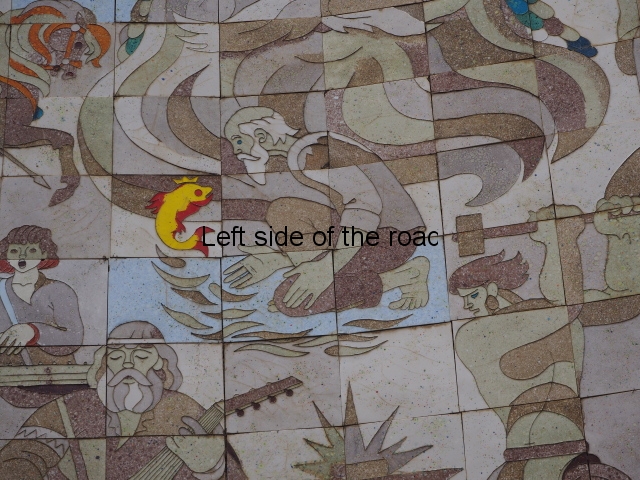

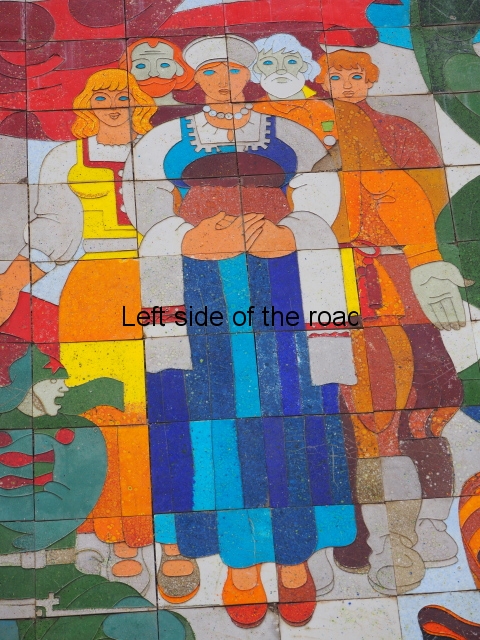

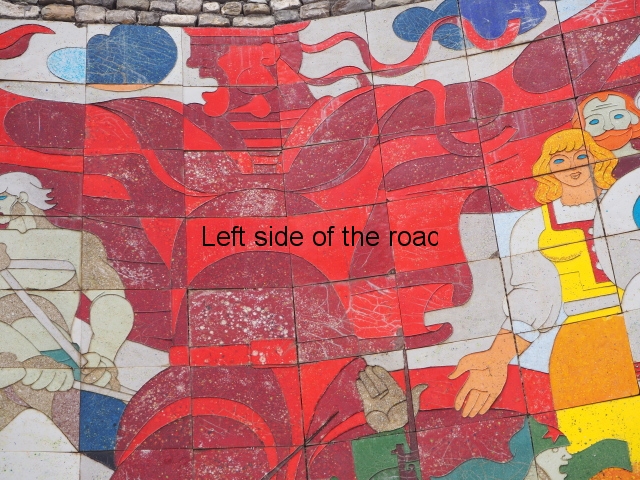

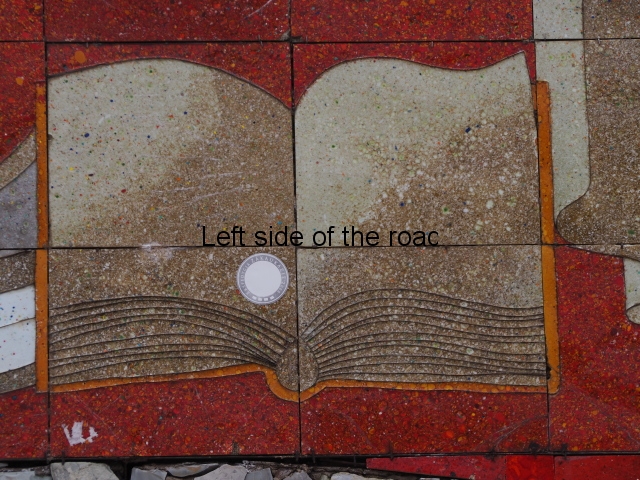

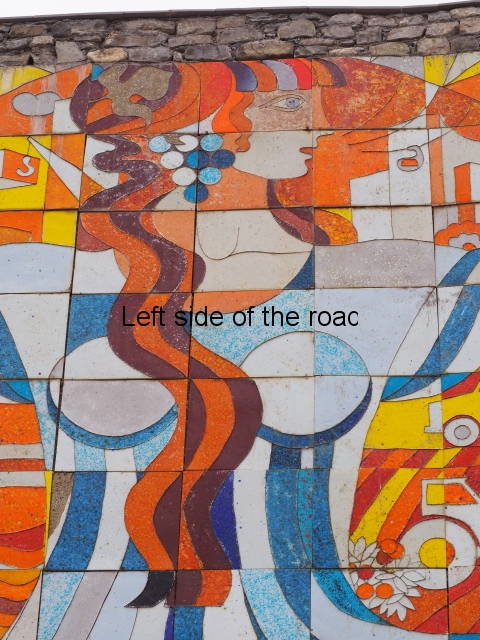

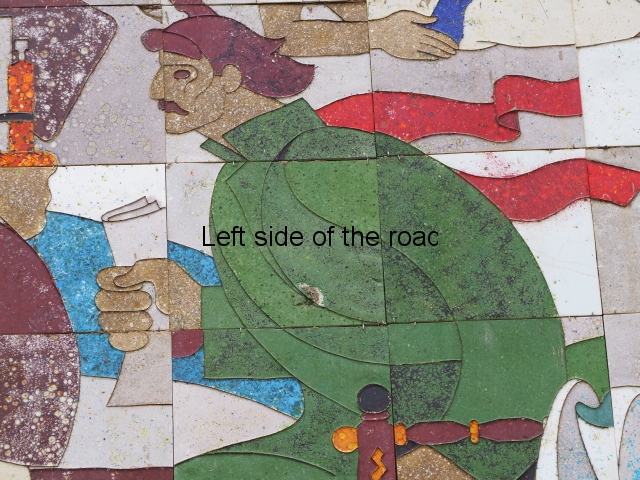

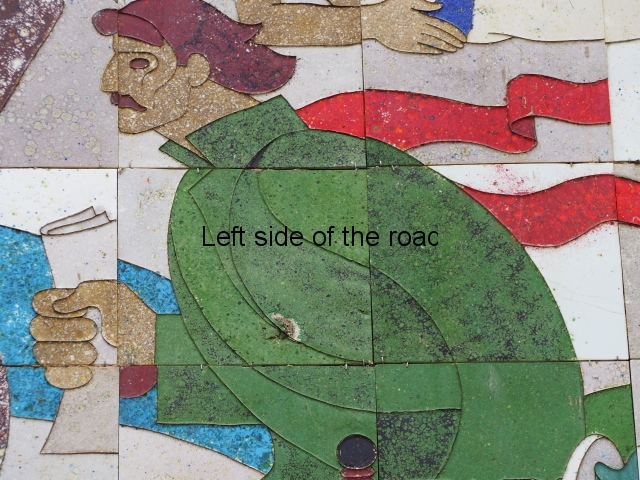

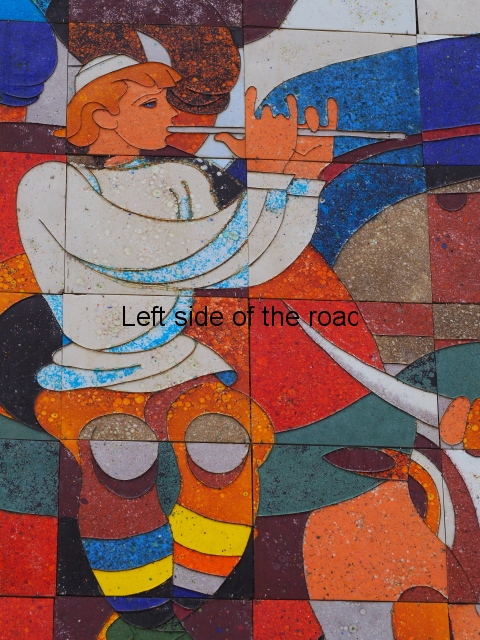

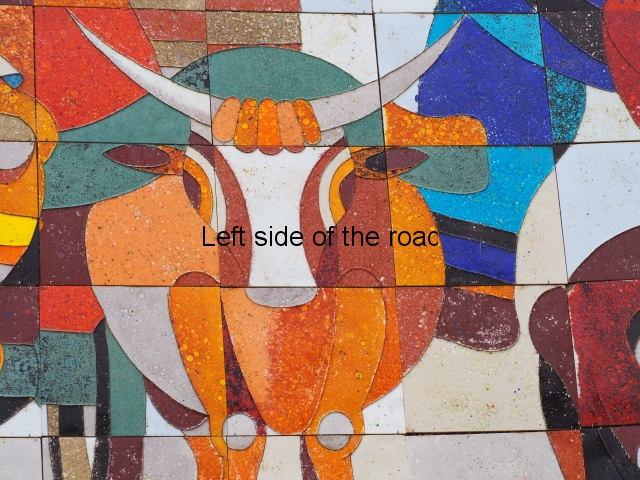

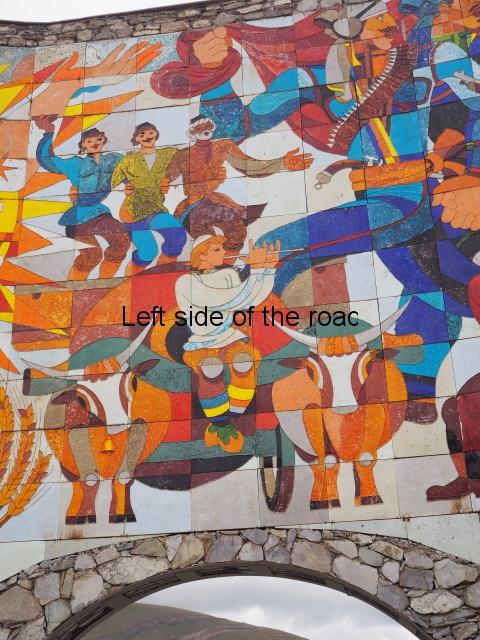

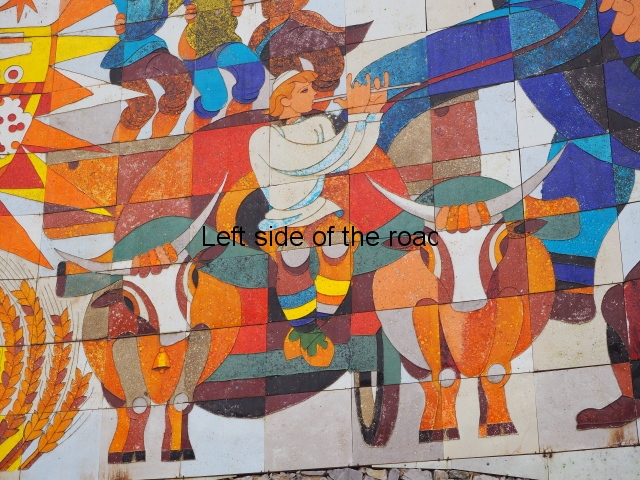

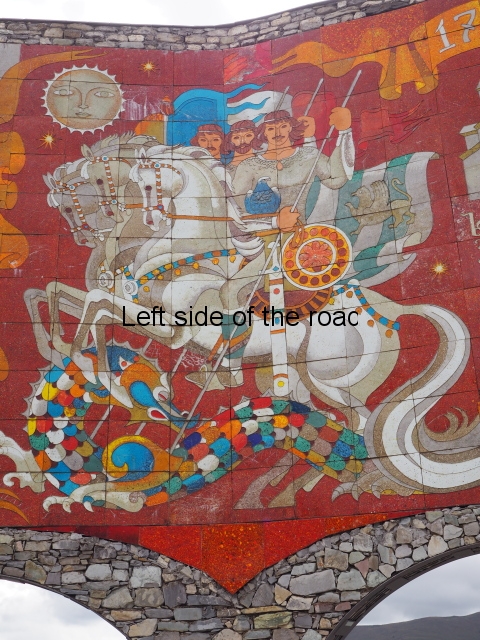

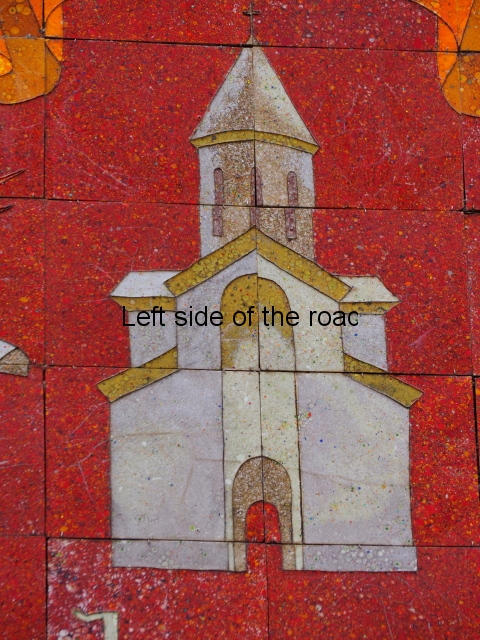

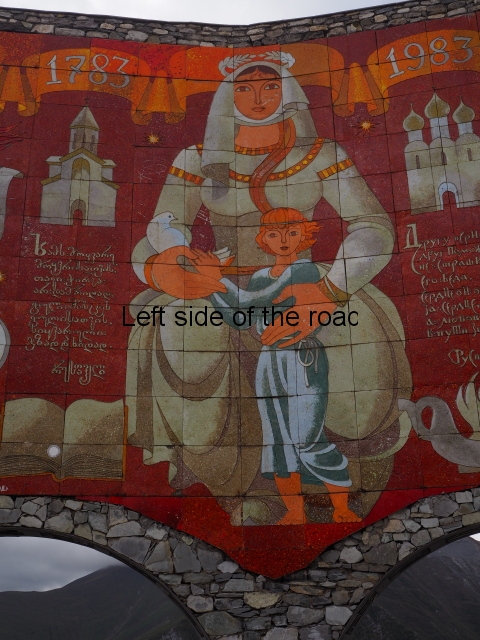

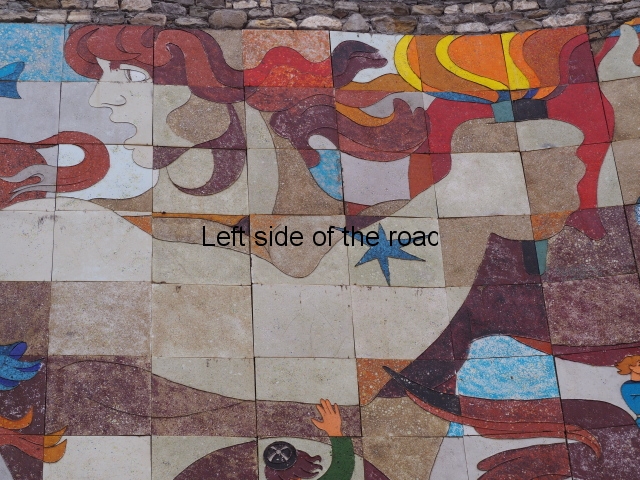

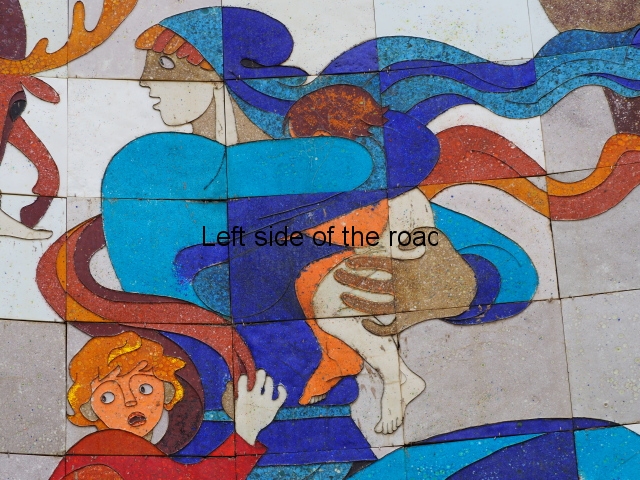

Then there is ceramic mural which takes the form of an ‘L’ shape, with a small part on the wall of the museum and then the longer side being on a wall that runs the length of the square. On here you see depicted both figures in the land army as well as those from the naval armed forces. As stated above no battles actually took place on Georgian soil but many Georgians did fight and die on the various fronts and those from Gori are memorialised inside the museum.

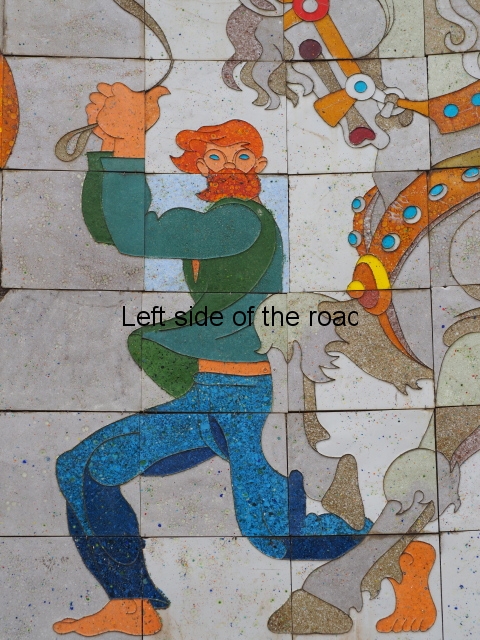

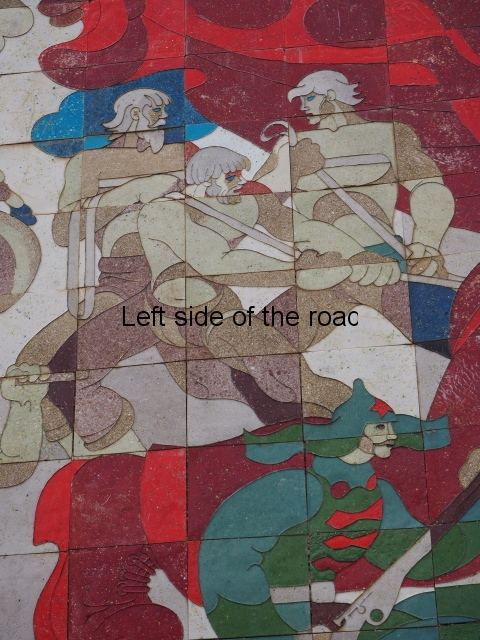

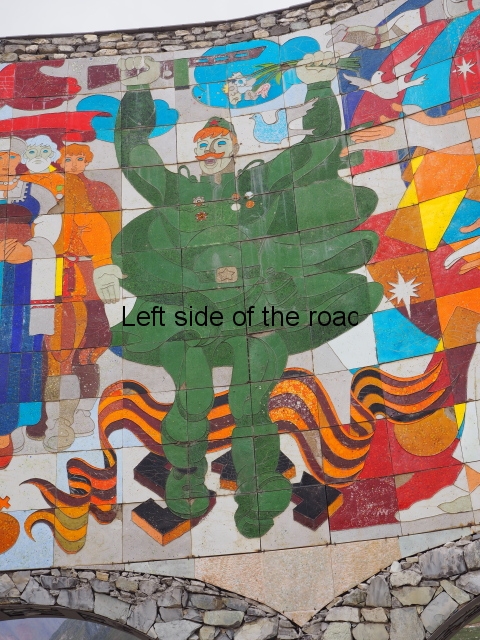

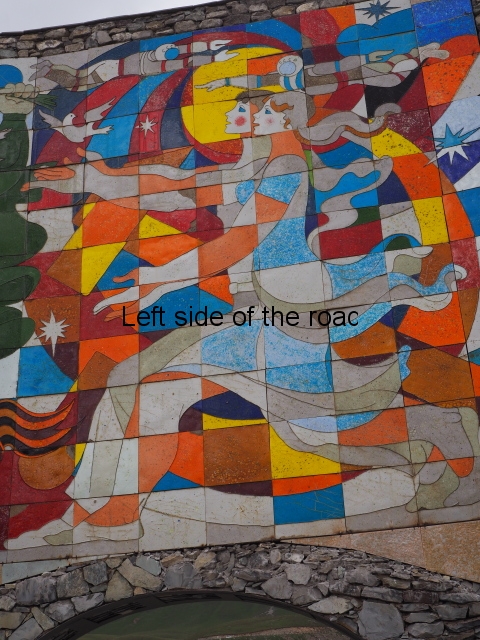

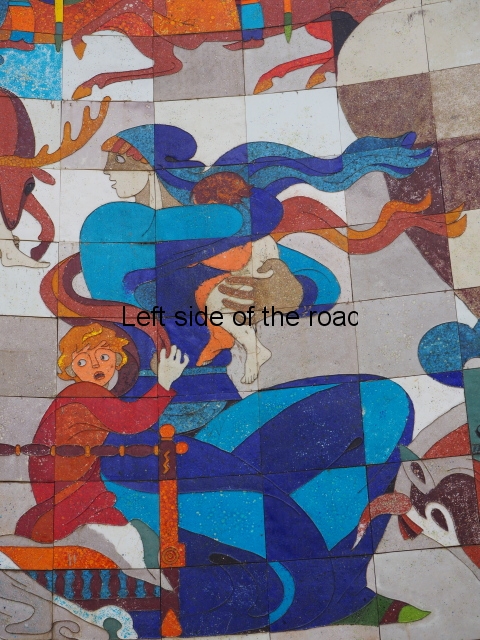

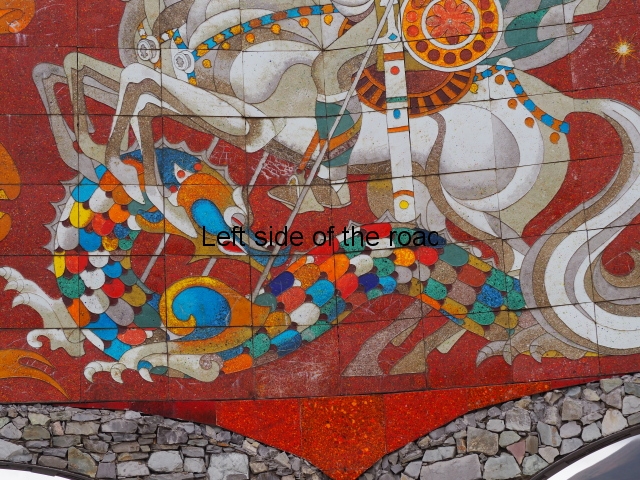

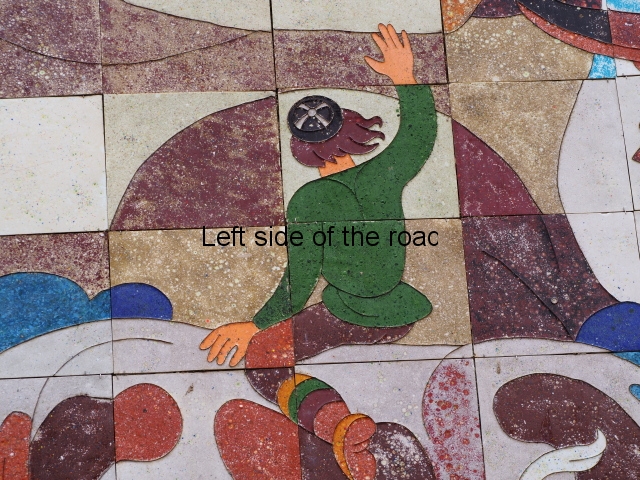

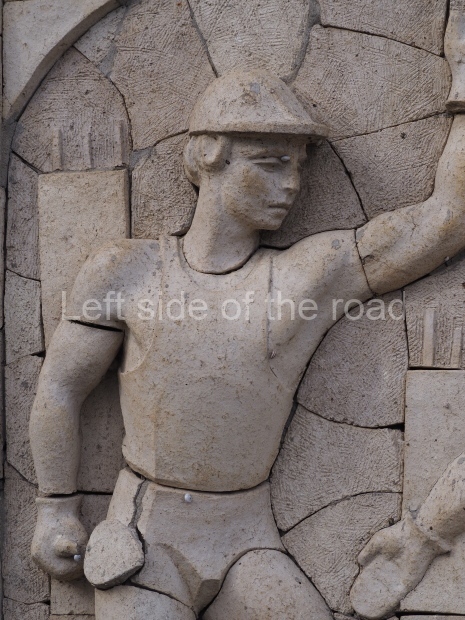

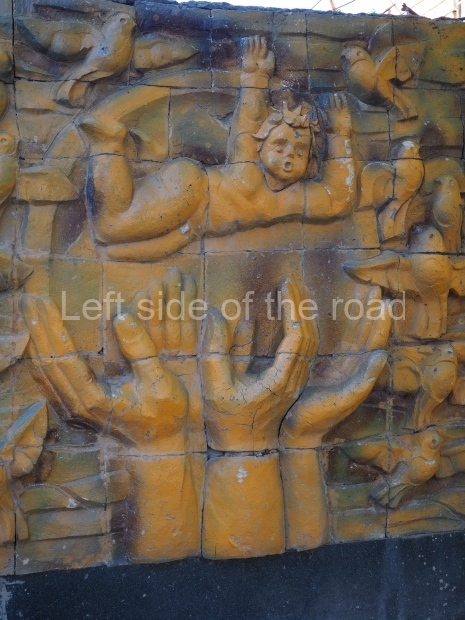

Georgian Socialist Realist art, especially when it comes to murals and bas reliefs, is very distinctive. The same can be said of the statuary of the period. In both those art forms the rounds are exaggerated as are the straight edges of the human form. This can be seen here in Gori but is also demonstrated on the Mother of Georgia – Kartlis Deda statue in Tbilisi; the wall panels next to the Bodorna Hydroelectric plant (along the ‘military road’ which goes up to the Russian border at Kazbegi); and the mural on the side of the telephone exchange in Tskaltubo.

The specific Georgia style gives the figures an almost comic aspect. This is enhanced by the fact that the murals, at least the majority I’ve seen, are made up of smaller sections (whether ceramic or stone) and the spaces between the blocks give the impression that the figures are string puppets where there are gaps between the joints.

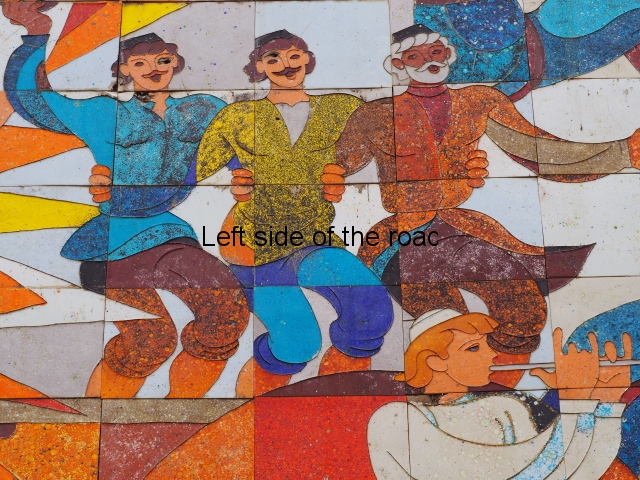

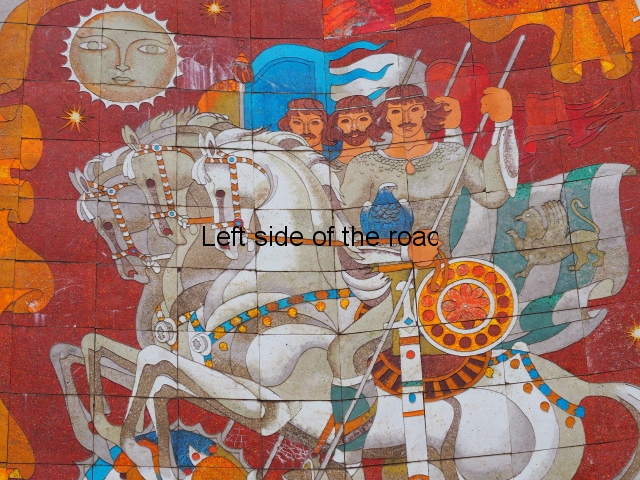

The first group of three, on the museum wall, are sailors and the ’rounding’ of the figures makes them out to be burly, muscle bound bruisers and the exaggerated cheeks bones make them out to be the picture of health.

This style also appears to make the figures less serious in their demeanour. In the first group along the long wall, nearest the museum, we have a group of sailors marching in formation. Some of them are looking at the viewer and seem happy that they are going off to war.

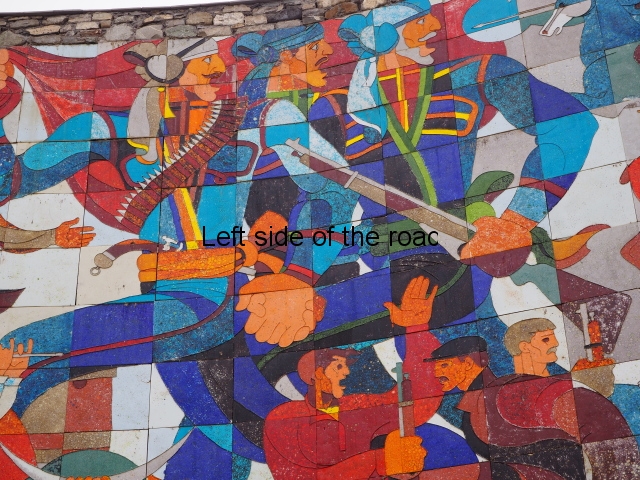

In the centre of the long wall (now partially obscured by an Christian cross, part of the monument to the Russo-Georgian War of 2008) is a group of three soldiers, giving a clenched fist salute – the sign of victory.

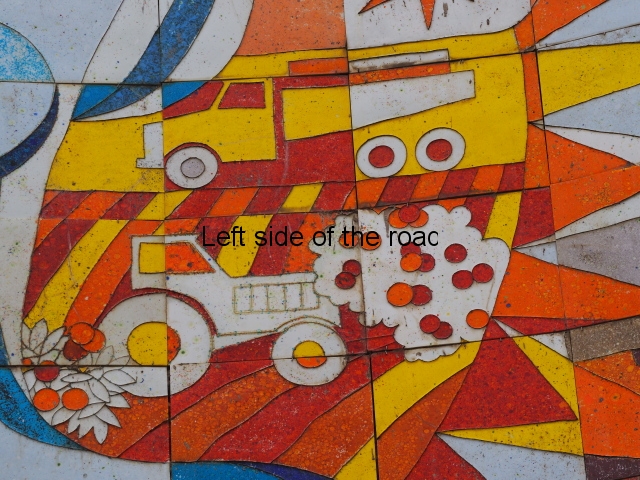

The Soviet symbol of the the Hammer and Sickle appears underneath the dates 1941-1945 (the duration of the war) and stars surround the figures of the left side of the wall.

Everything changes on the right of the dates where we see a celebration of peace, a child being protected from its fall by open, outstretched hands with images of doves flying around behind.

A few metres in front of the central part of the long bas-relief is a small stone circle that, at one time, would have housed the Eternal Flame. When this ceased to be in use I don’t know but seems to represent a denial of the sacrifice of Georgians in the struggle against Nazism in the 1940s – because it was the Soviet Union for which they fought. This is also reflected in the manner in which the War Memorial in Vake Park, in Tbilisi, has been allowed to go to rack and ruin.

Related;

Stalin Museum – Gori

Gori – Rediscovered statues of Joseph Stalin

Museum of the Great Patriotic War – Moscow

Location;

19 Stalin Avenue (between the Stalin Museum and the Town Hall square)

GPS;

41.98387º N

44.11199º E

Opening times of the Museum;

Tuesday to Sunday (closed Mondays) from 10.00 to 17.00

Entrance;

3 GEL

More on the Republic of Georgia