Vake Park – 01

More on the Republic of Georgia

Vake Park, Tomb of the Unknown Warrior and the Mother of the Place, Tbilisi

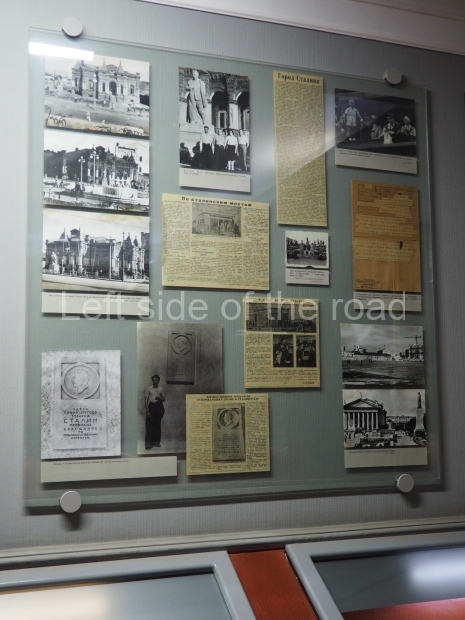

The War Memorial in Vake Park, on the edge of Tbilisi centre, has gone through a process of evolution (and then regressed) over the years. However, it’s not easy to find definitive information of when and who.

The park, which might have existed before the Great Patriotic War, became Victory Park in 1946 and a war memorial installed. This would seem to have been a relatively simple affair, possible just a simple ground level marble slab covering the ‘Unknown Warrior’ in front of which was an eternal flame.

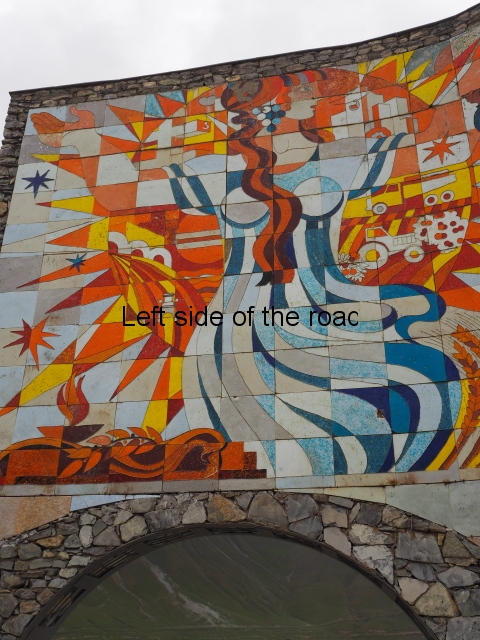

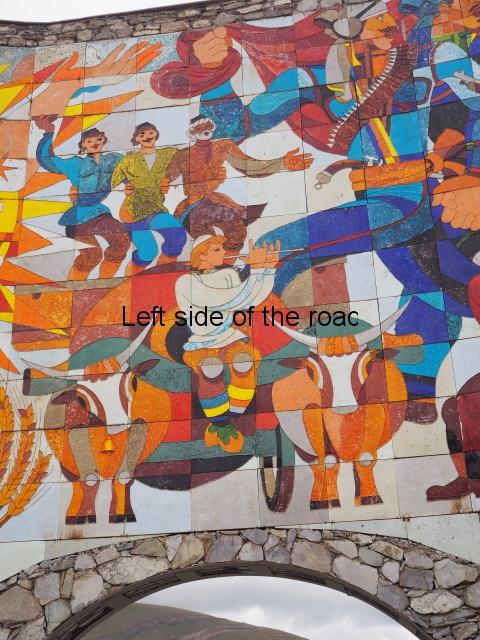

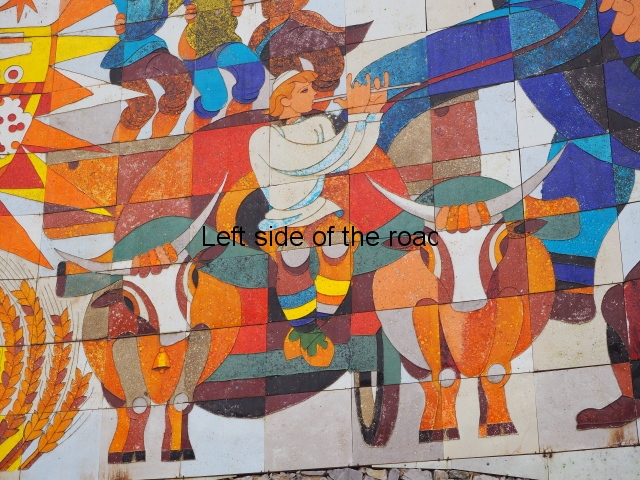

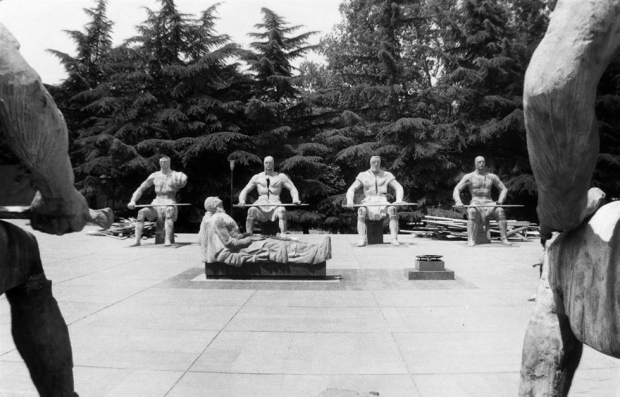

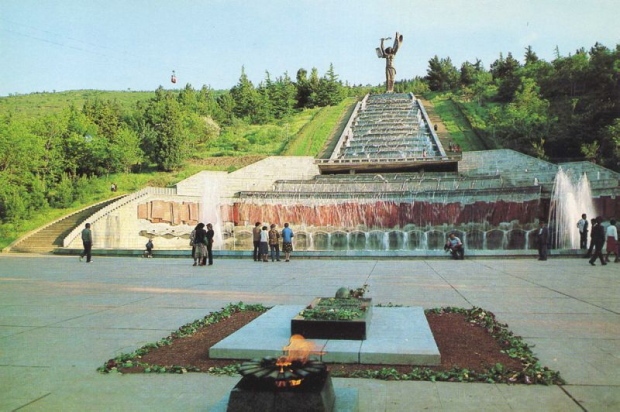

Although I’m not certain of the exact chronology it seems matters remained simple until the beginning of the 1980s. Between 1981 and 1985 there was a major construction project that; involved the building of the cascade and fountains in the hill behind the flame; the installation of the 18-meter bronze statue of the Mother of the Place at the very top of the monument; the installation of the eight (of what have now been called the) Georgian Warrior Heroes, guarding the tomb; then the installation of the statue above the tomb and the resitting of the eternal flame, this time with the flame emerging from a red marble star rather than just being an open flame.

All this happened in stages as is illustrated in a photograph from the period.

Tomb of Unknown Warrior and Eternal Flame before 1981

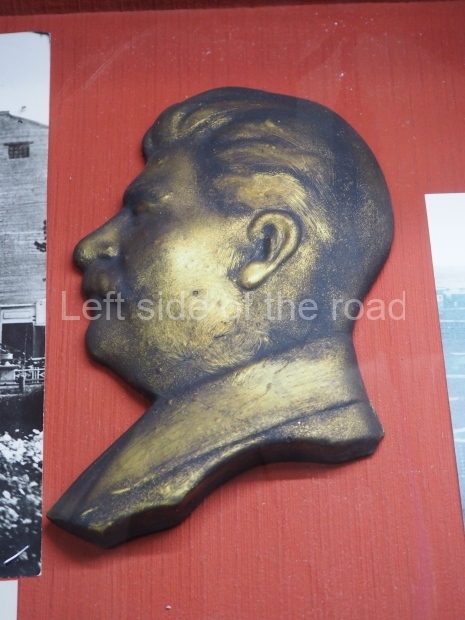

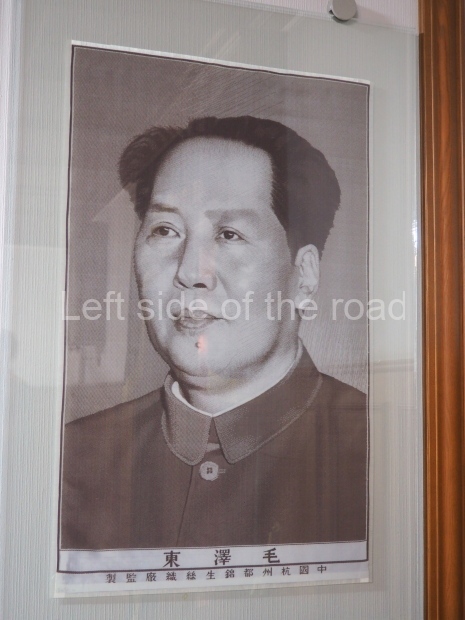

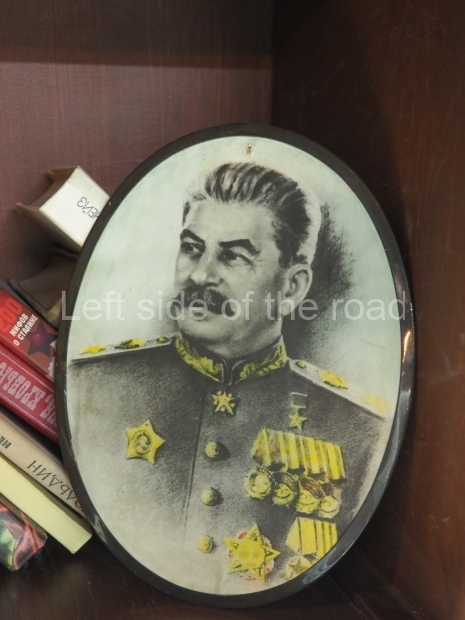

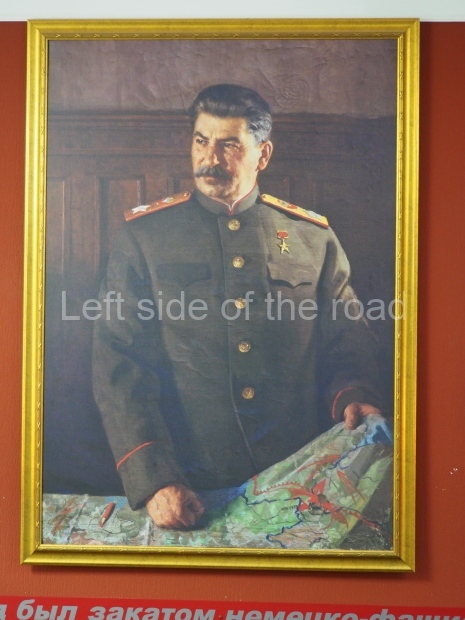

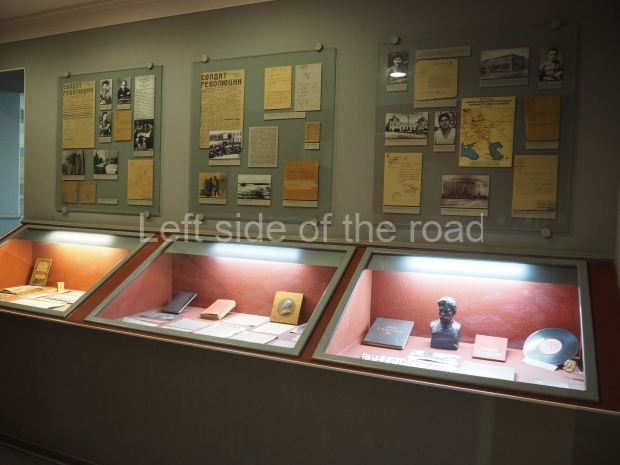

The sculptor of the Mother of the Place and the eight Warriors were created as a package and are the work of Gogi Ochiauri. To me the ‘warriors’ seemed out of place in this park and, although many years later, someone else agreed as in 2009 they were moved and now are installed in a small garden just below the fortress in the town of Gori (the town of Stalin’s birth and the location of the Stalin Museum).

Vake Park – 03

As far as I understand the architects of the reconstruction were; V. Aleksi-Meskhishvili, O. Litanishvili, K. Nakhutsrishvili.

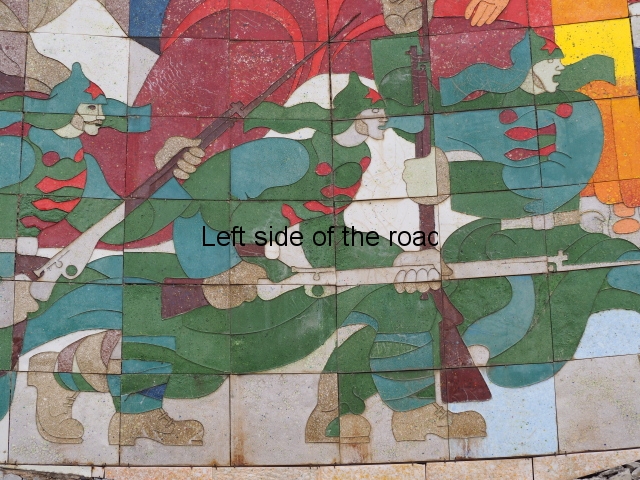

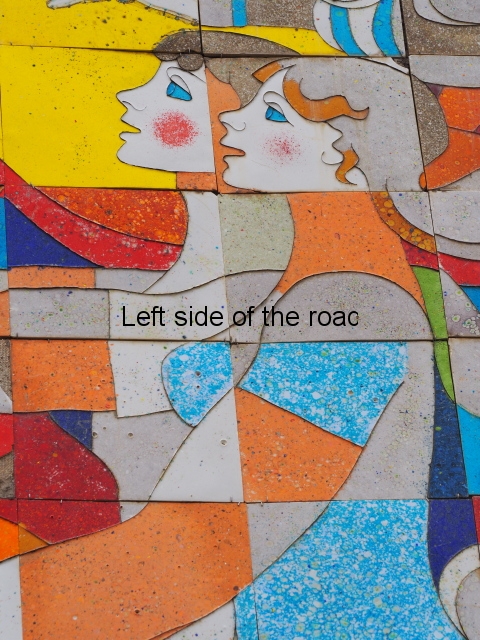

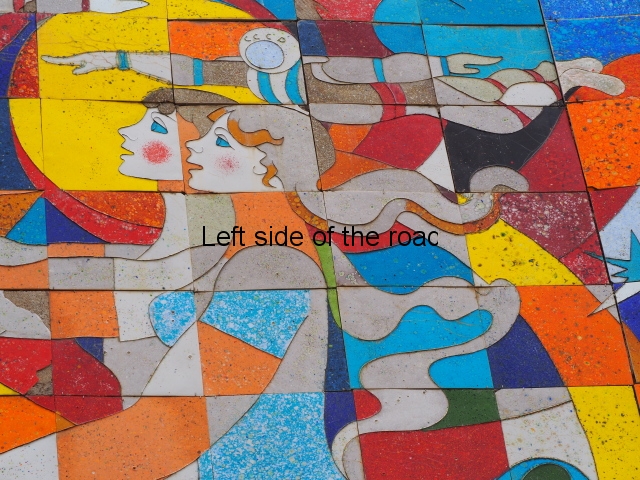

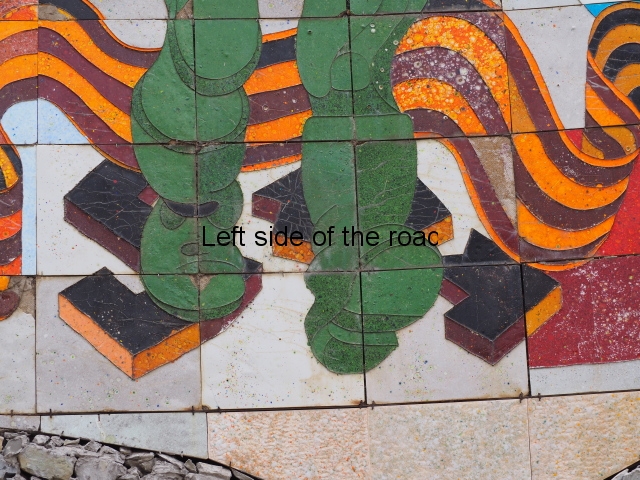

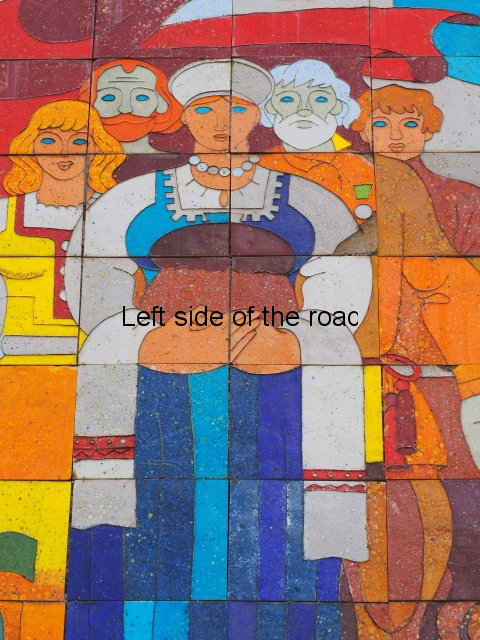

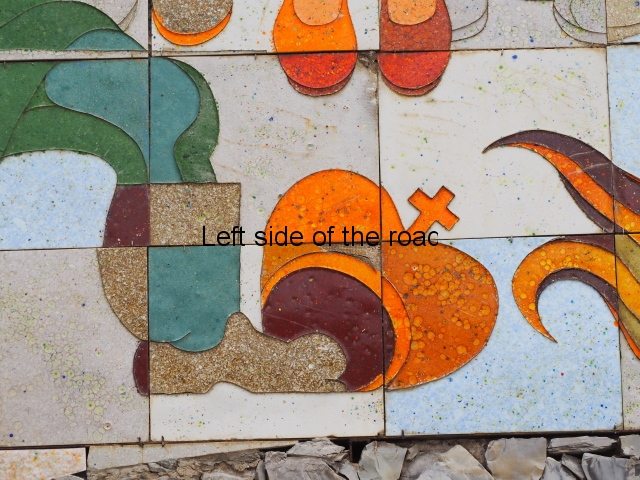

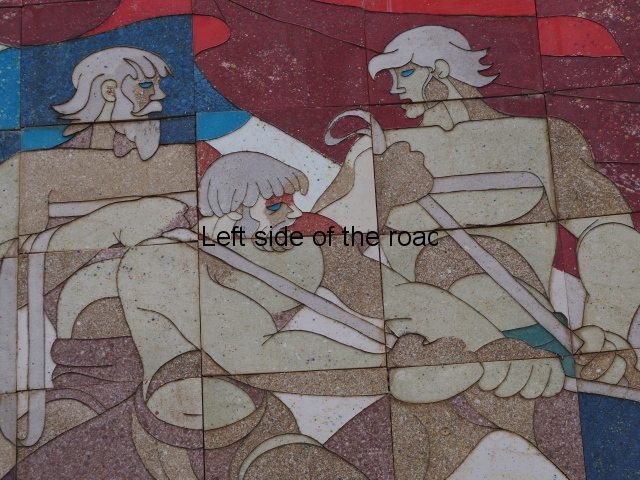

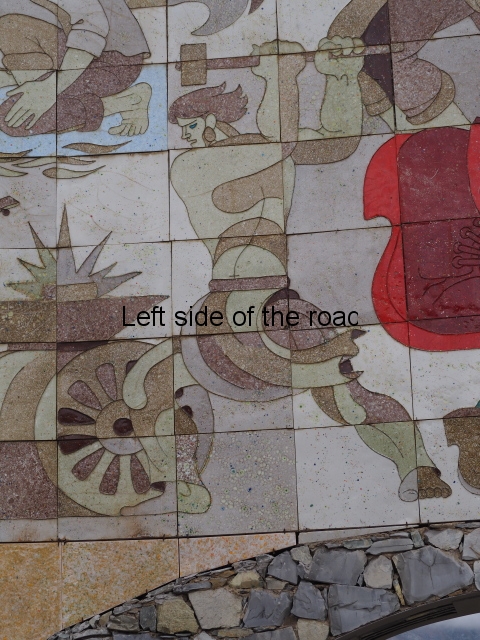

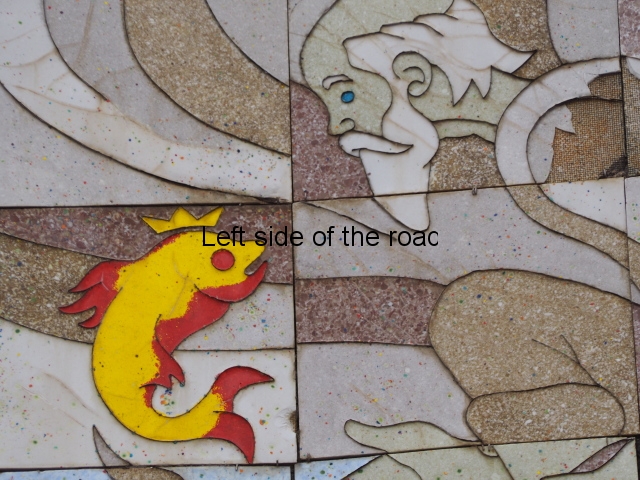

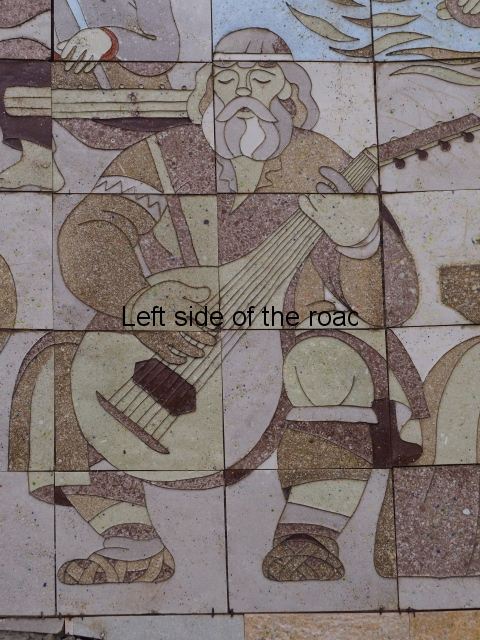

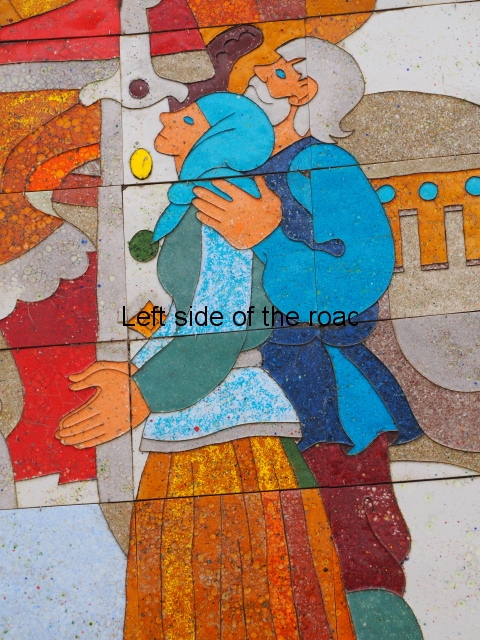

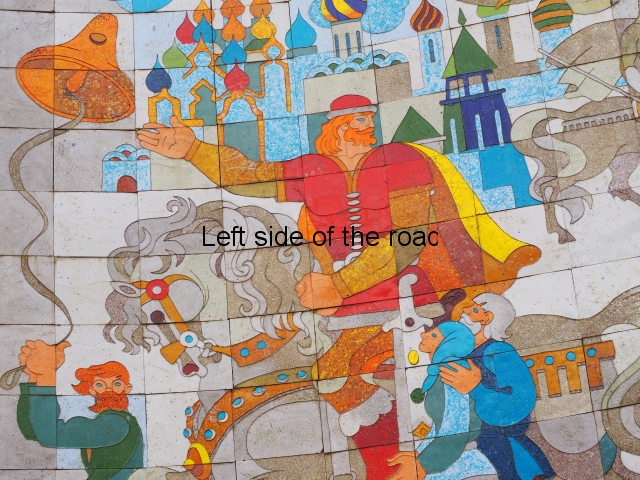

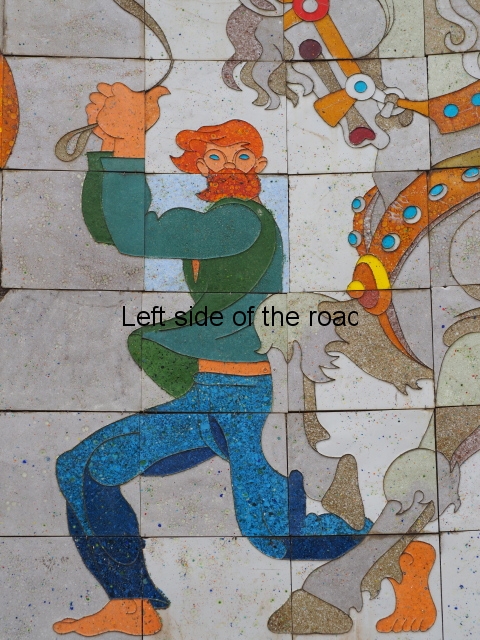

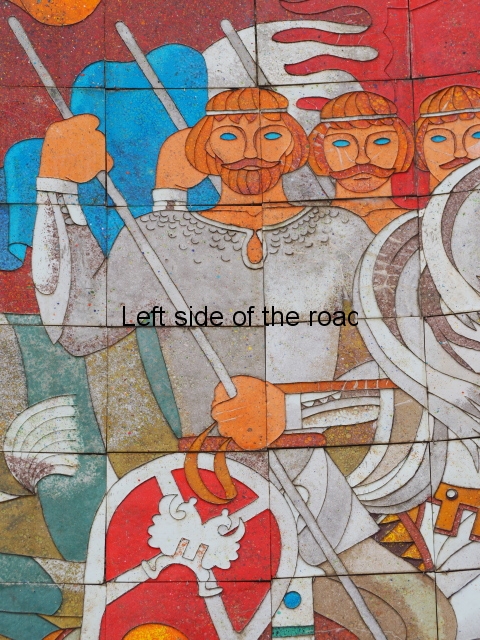

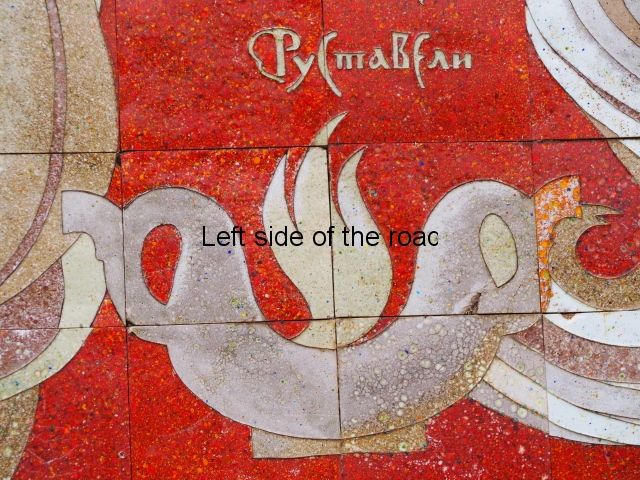

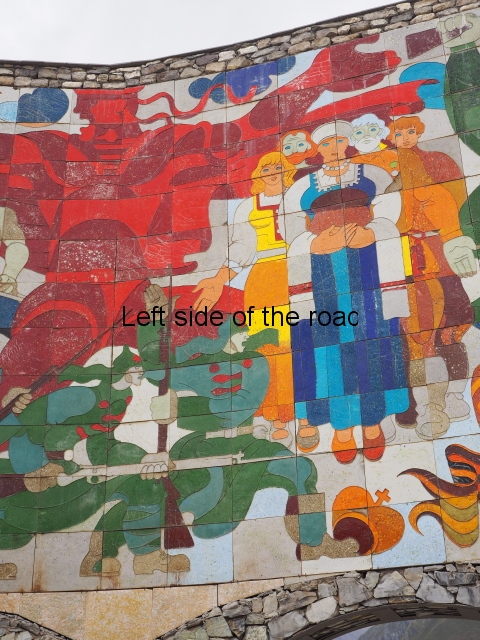

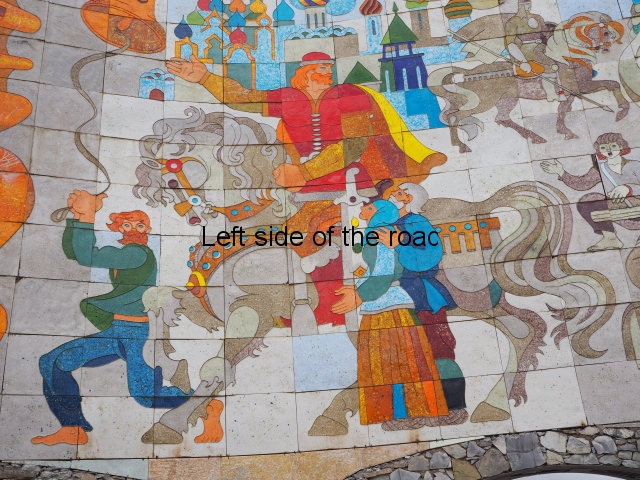

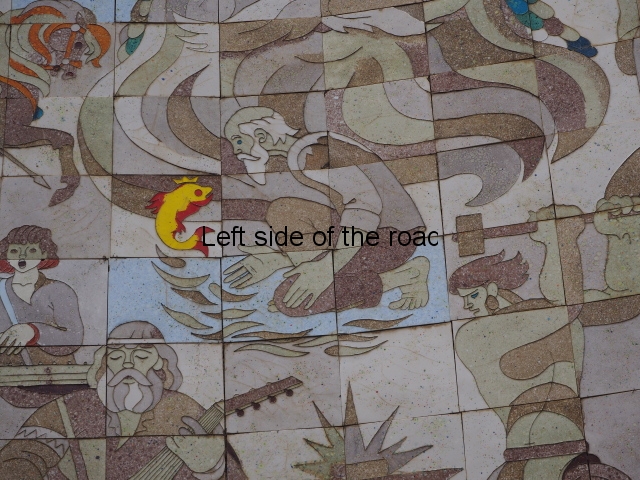

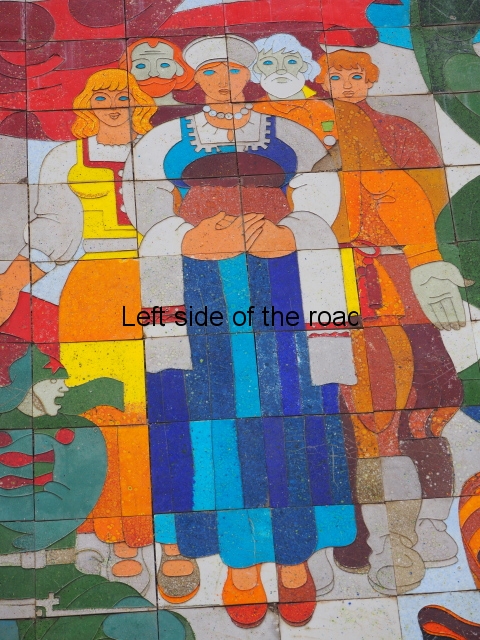

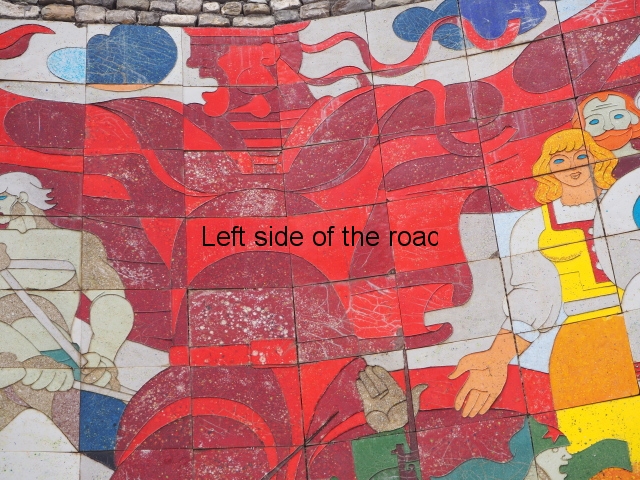

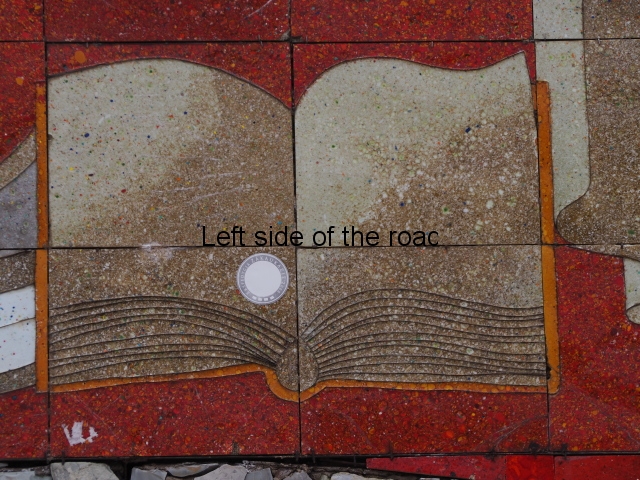

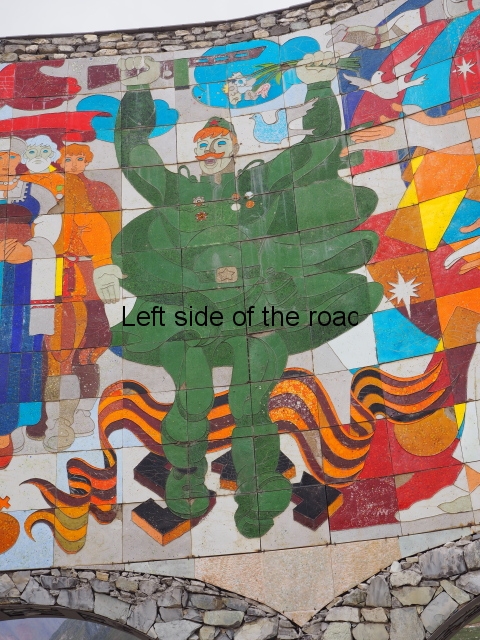

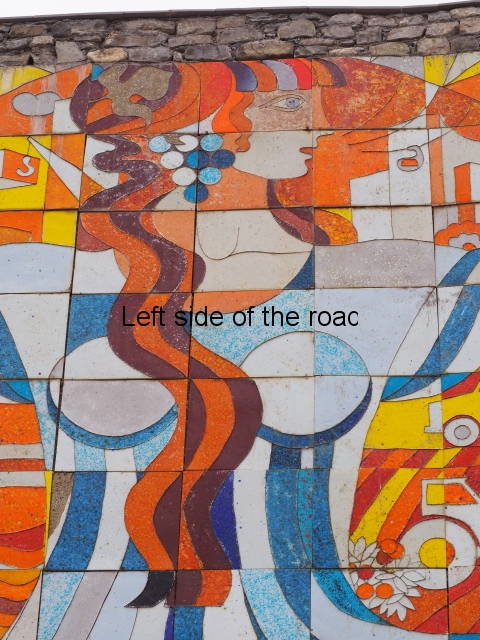

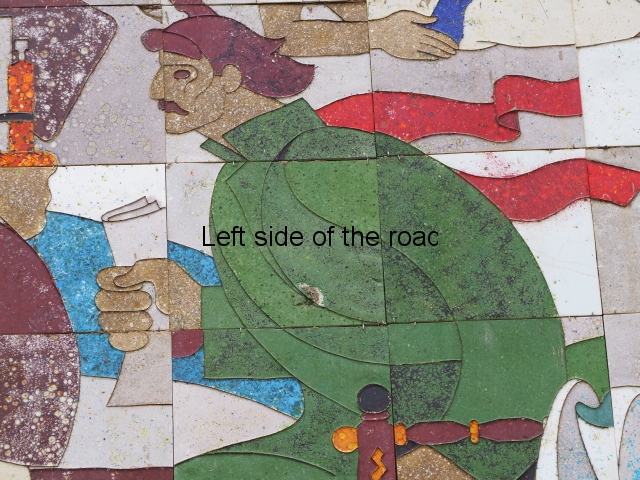

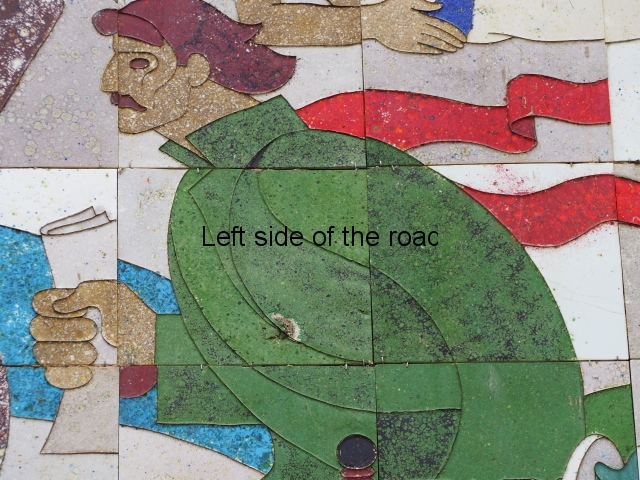

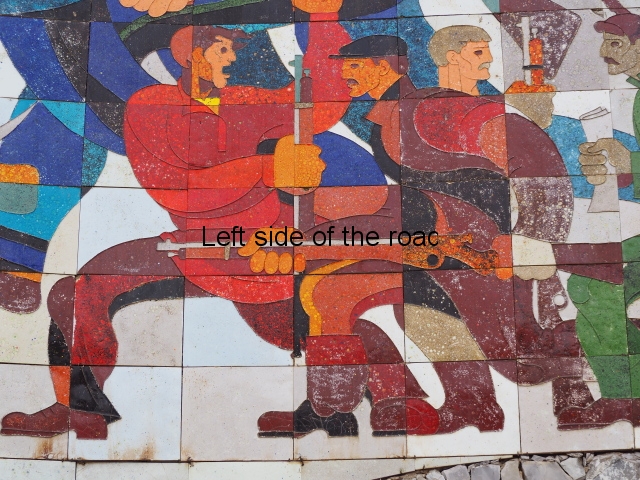

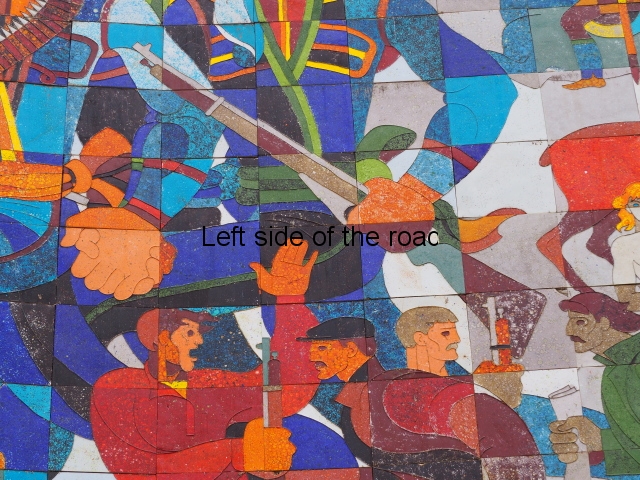

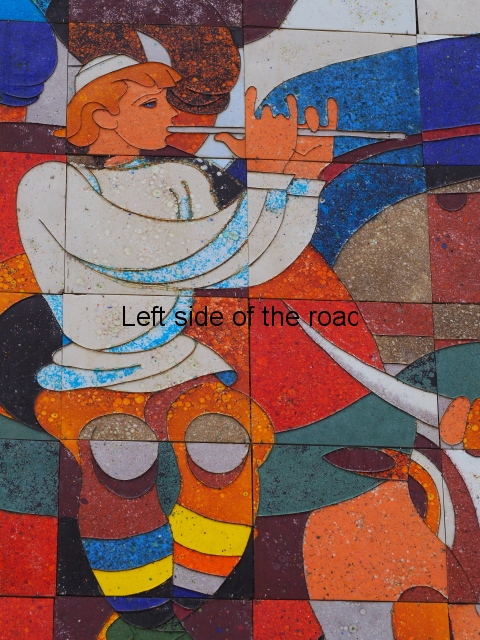

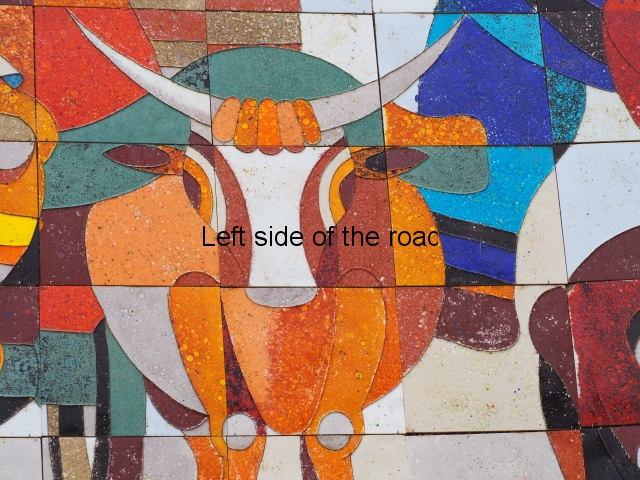

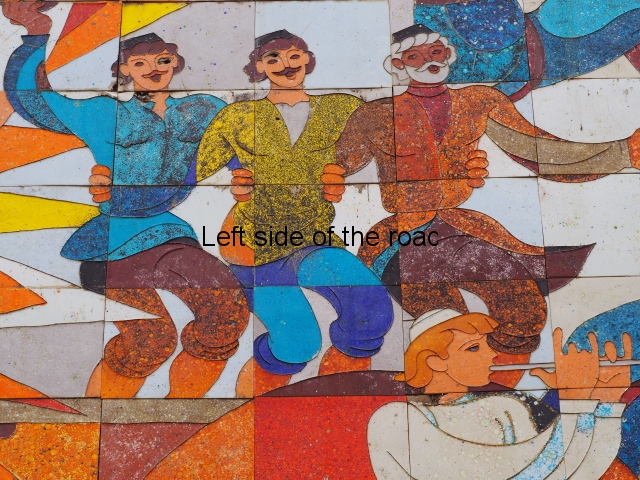

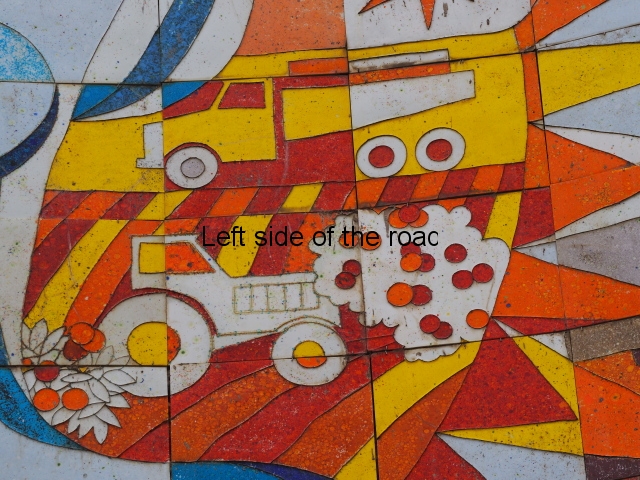

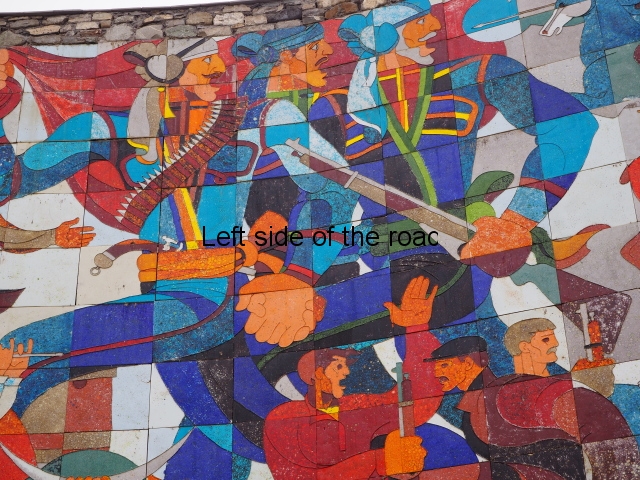

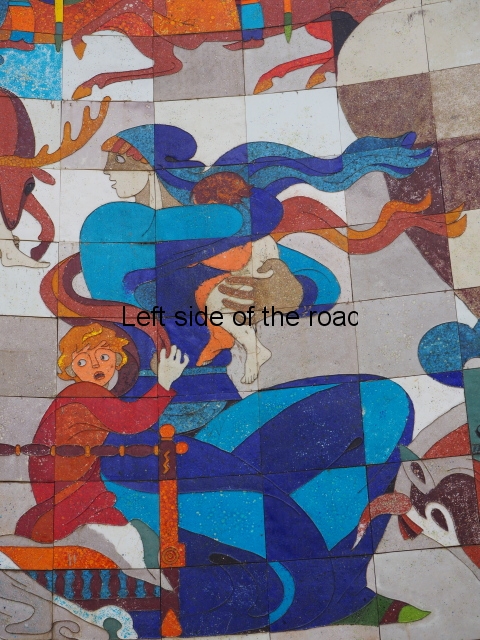

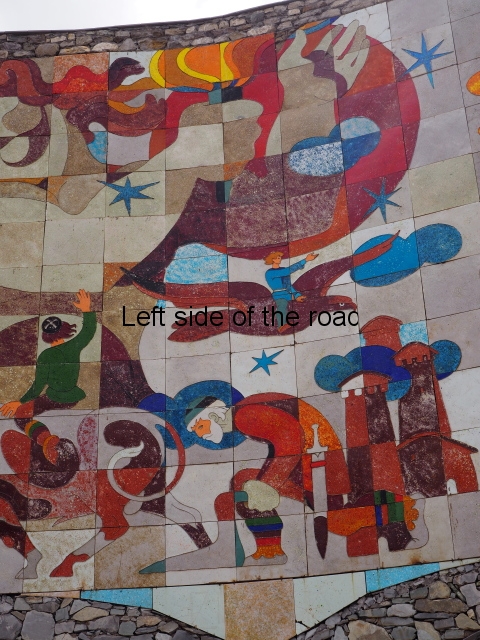

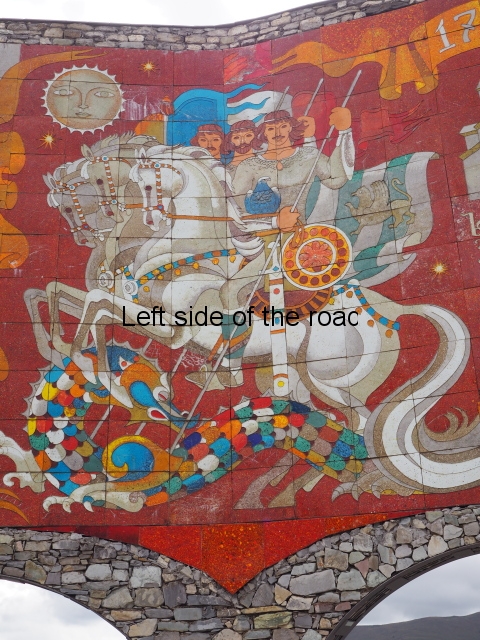

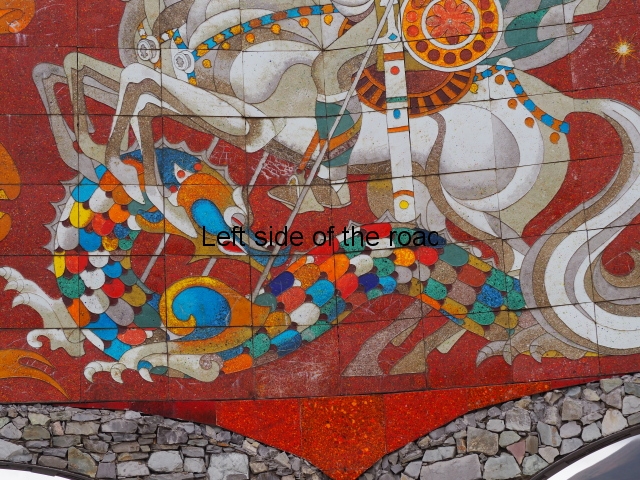

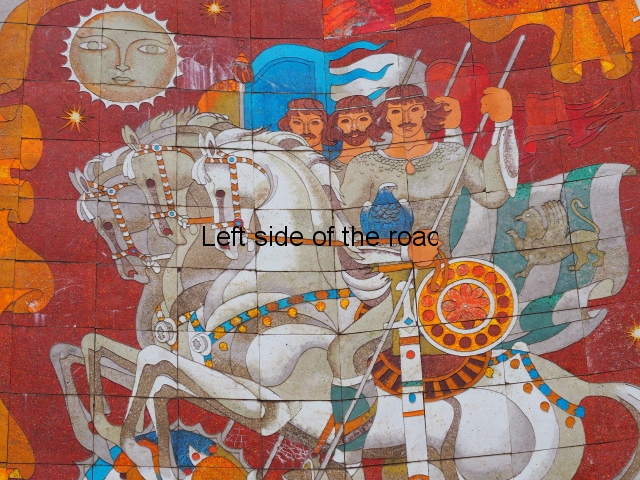

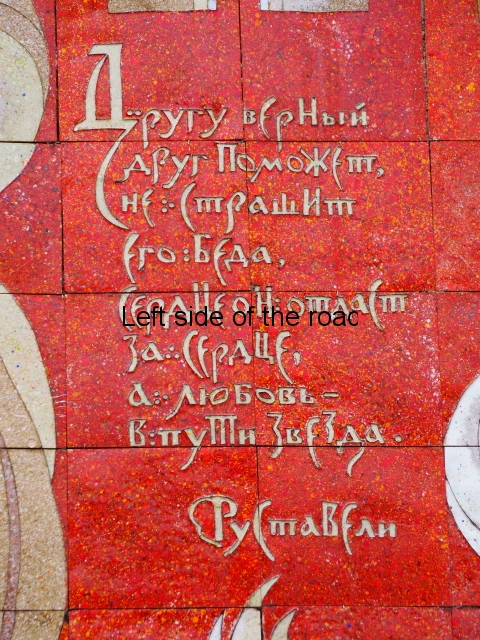

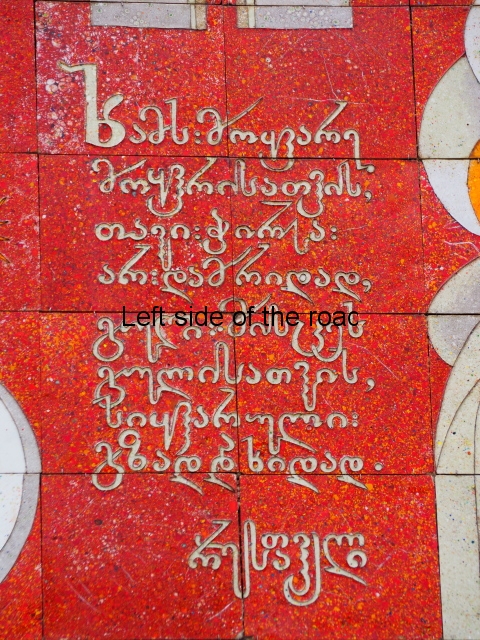

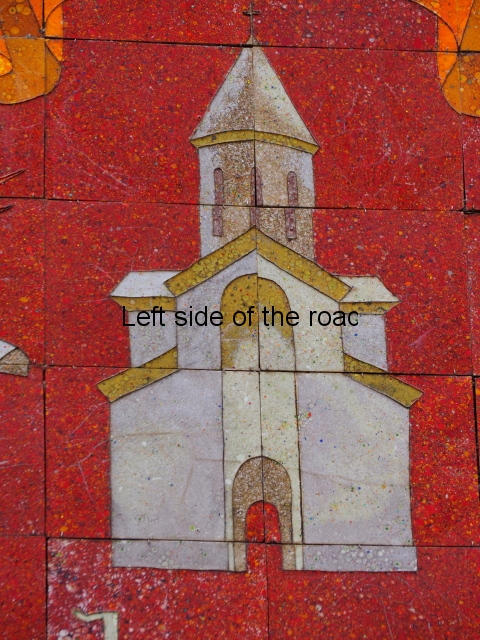

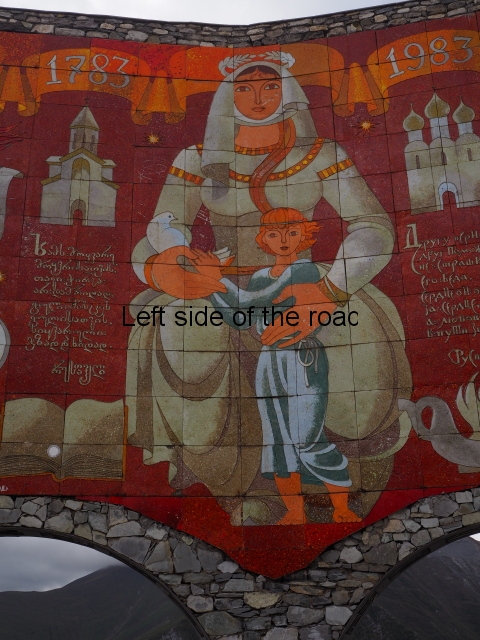

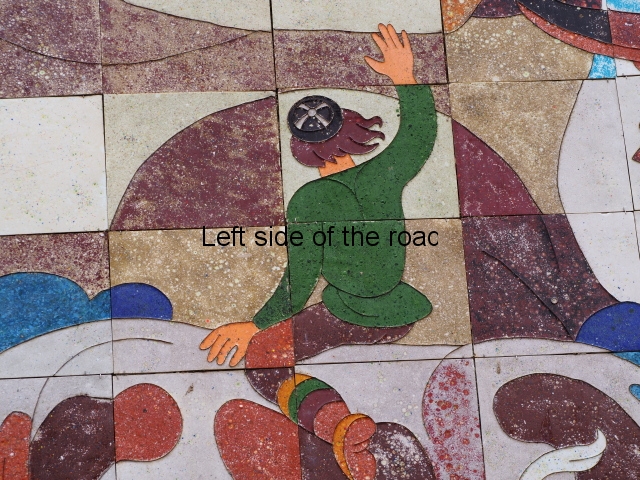

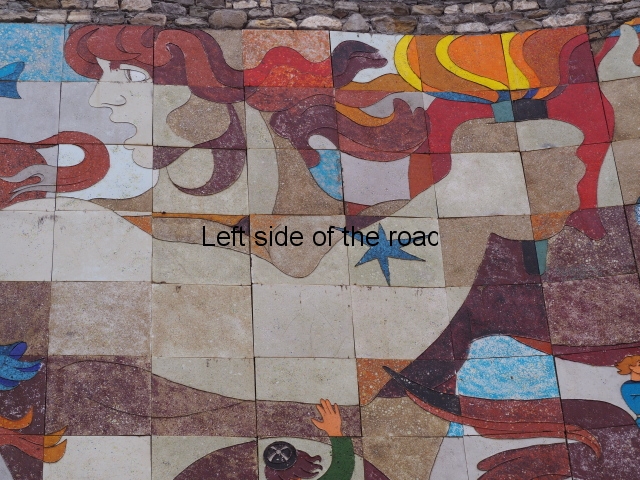

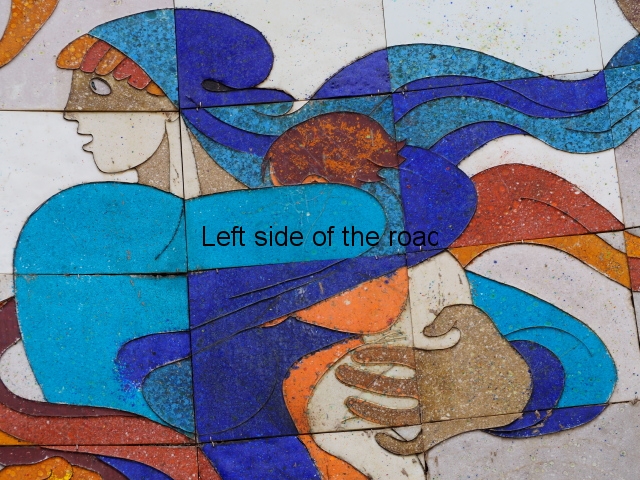

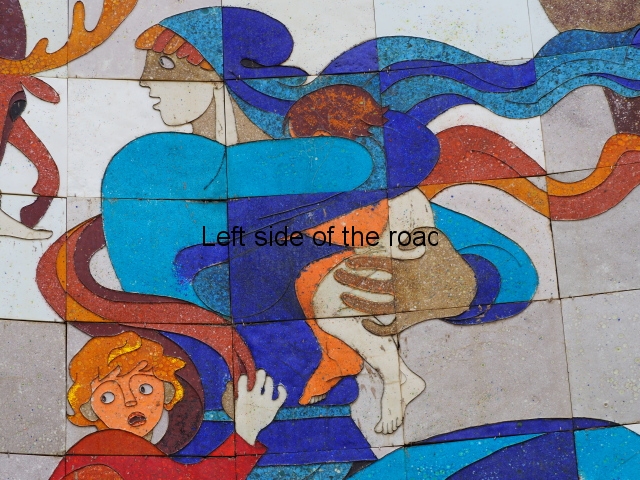

Zurab Tsereteli is also listed as being involved. He was a sculptor and artist who specialised in mosaics – he was responsible for, among others, the Russian-Georgian Friendship Monument at Gudauri, off the ‘military road’ from Tbilisi to the Russian border – so it’s likely he was responsible for the decoration of the fountains and cascade, the line of Georgian red and white flags at the rear of the lower pond and the numbers 1941 and 1945 – the years between which it took to defeat the Nazi hoard.

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Georgian: უცნობი ჯარისკაცის საფლავი) commemorates the hundreds of thousands of Georgian soldiers who served and died in the Red Army during the Great Patriotic War. It’s possible the creator of this monumental sculpture was Nikola Nikolov. The monument was opened officially by Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Georgian SSR Eduard Shevardnadze, as part of the diamond jubilee of the republic in 1981.

Vake Park – 02

The monument used to be guarded by a ceremonial guard from the National Guard of Georgia, changing every hour in a formal ceremony, as is/was the case in many such locations throughout the Soviet Union. However, this has ceased since elements in Georgia started to court the ‘West’.

Whether the ‘eternal’ flame is ever lit now I can’t say. It’s possible it might be in operation when Georgian veterans of war and residents of the capital gather at the tomb to commemorate holidays such as Victory Day (9th May). As for the fountains those lower down might be functioning but I have my doubts of those above the level of the tomb.

This area has been neglected for years. The area around the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior is still kept tidy(ish) but the waterfalls that were created by water cascading from just below the statue of the Mother of the Place high up the hill are now little more than ruins. The steps on either side of the cascades are now no longer easy to negotiate by soil brought down by the rains as there is no longer any regular maintenance.

Location;

76 Ilia Chavchavadze Avenue

GPS;

41°42′30″N

44°45′5″E

More on the Republic of Georgia