Central Museum of the Armed Forces of the USSR/Central Armed Forces Museum – Moscow

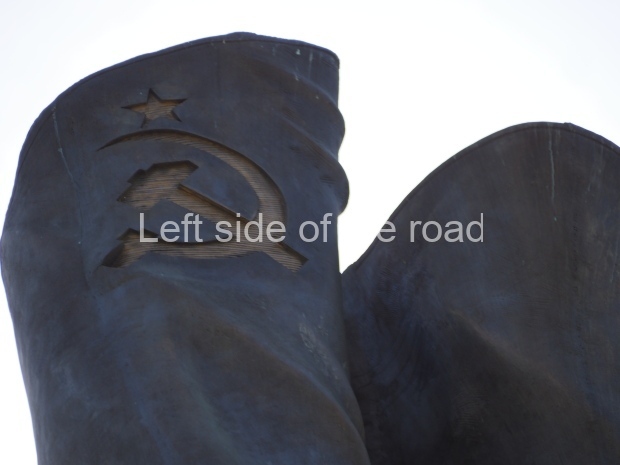

The main reason I wanted to go to the Central Museum of the Armed Forces of the USSR/Central Armed Forces Museum in Moscow was because I had learnt that it was there that the Nazi banners that had been thrown into the mud at the base of the Lenin Mausoleum (with Comrade Stalin accepting them on behalf of the Soviet people) on the first Victory Day on May 9th, 1945, were presently on display.

On my first visit to Moscow (way back in 1972) these banners were in a huge glass case which covered the whole floor of a room in what was then the Museum of the Revolution. This was up by Pushkin Square and close to the Izvestia offices. However, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the chaos that followed in the 1990s anything which smacked of revolution was a no-no and that particular museum went through a number of manifestations. In the process much that had been on display pre-1990 disappeared and it is only relatively recently that some of it has begun to be, yet again, on display to the general public.

(What used to be the Museum of the Revolution is now called the Museum of the Modern History of Russia – Muzey Sovremennoy Istorii Rossii. Although there are some interesting and valuable artefacts which help in the telling of the history of the Soviet Union following the October Revolution it is generally a poor shadow of what it once was. The final section, ‘bringing things up to date’, is more like something you’d expect at an international exhibition than a museum.)

However, I think the Central Museum of the Armed Forces of the USSR/Central Armed Forces Museum has much more to offer than just the Nazi banners on the floor. There is a manner in which to display objects to show utter contempt for what they represent. From my memory that was achieved in the original location in the centre of the city but there’s less of that impression (to my mind) in their present location, even though they are still displayed in cases on the floor.

From my experience Russian museums are crammed full of artefacts. Sometimes so many that very soon you feel assaulted by so many different objects. That being the case the best approach is to ‘skim’ what you pass, taking more time on anything, perhaps more unusual, that might catch your eye.

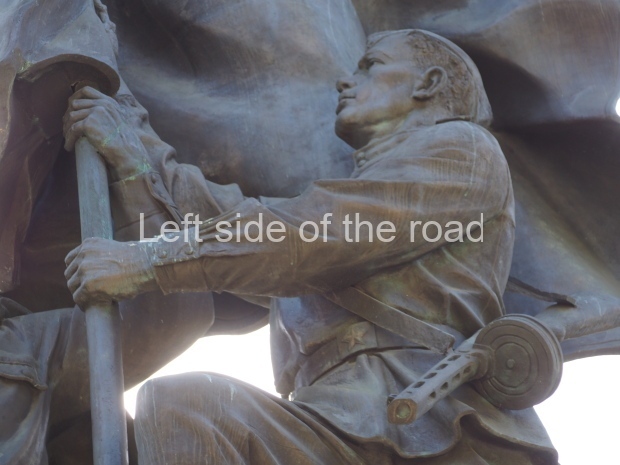

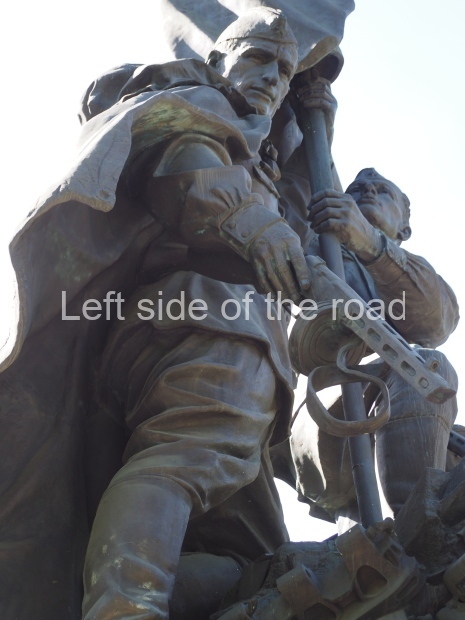

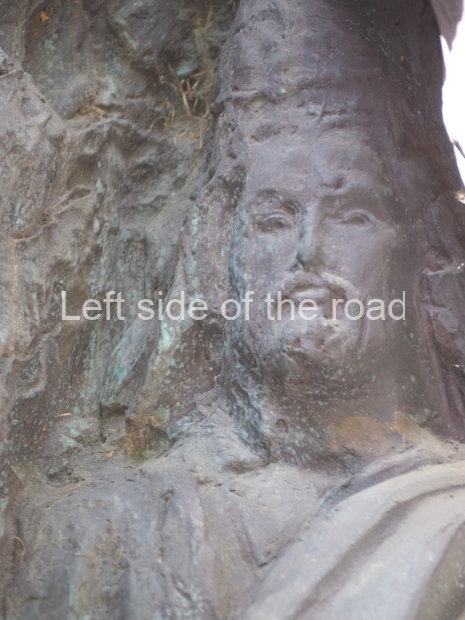

The starting point in the first room is the War of Intervention or the Civil War. This was when the Red Army was formed, first out of Bolsheviks and irregulars who volunteered to defend the Revolution from the reactionaries, both national and international. However, within a very short time this army took on the aspects of a fully organised and structured army which eventually was able to defeat all attempts to strangle the Revolution from birth.

Later rooms go through the events of the Great Patriotic War and into later, sometimes not well chosen wars (such as that in Afghanistan) and through to the present with a small room dedicated to the Special Military Operation in the Ukraine.

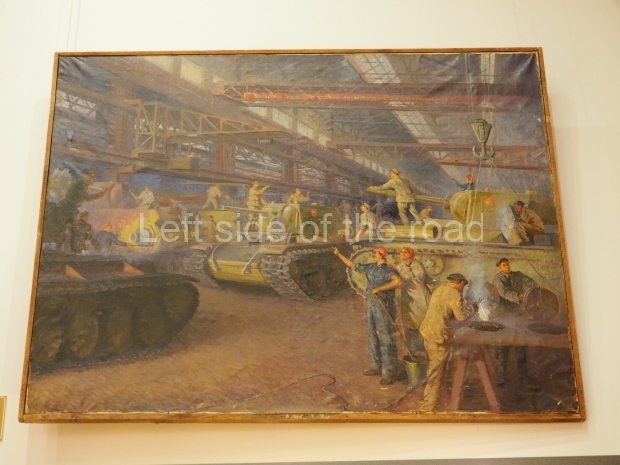

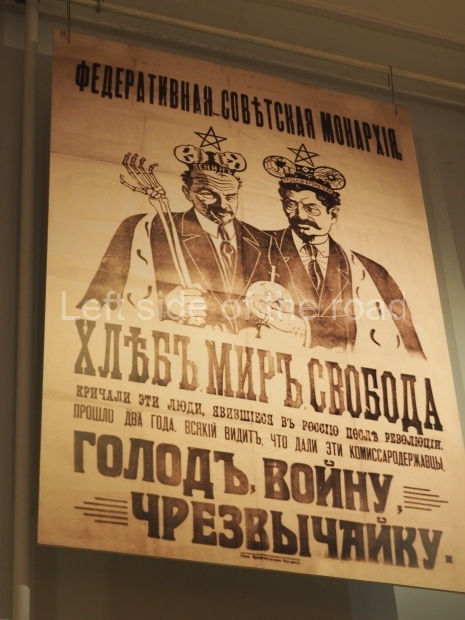

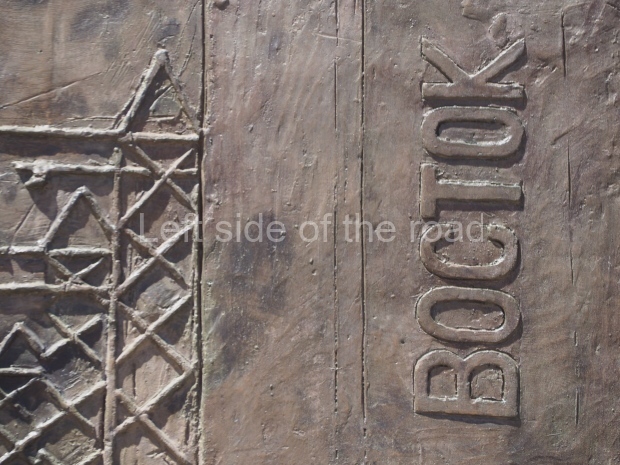

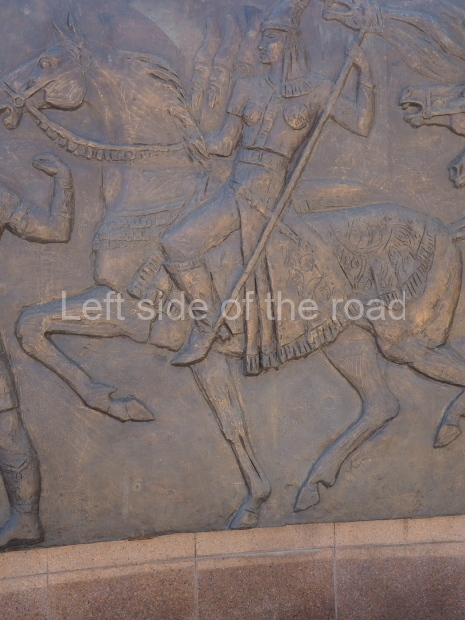

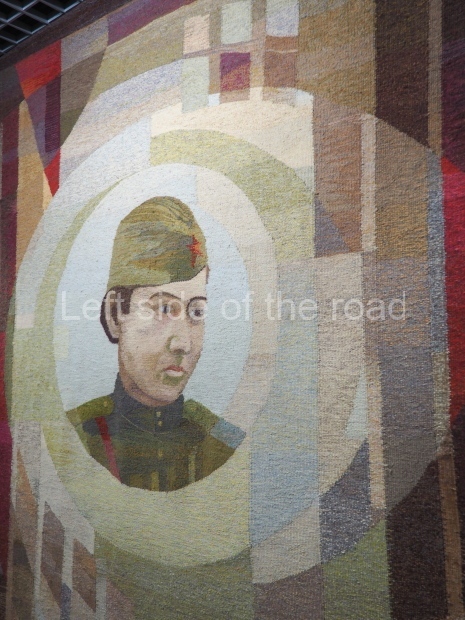

In the slide show at the end of this post you will see that I have concentrated on the various banners and standards under which those fighting to defend the Revolution fought, as well as artistic representations of those battles and achievements. There’s a limited depiction of military hardware as, with a few exceptions, these are more or less generic and were used by all fighting forces in any particular epoch or conflict. I find what is unique to the Soviet Union (the way it presented itself; the battle of ideas through posters and other types of propaganda; and how the struggles were presented to the masses to be much more interesting.

In any visit to the museum here are a few suggestions of what to look out for;

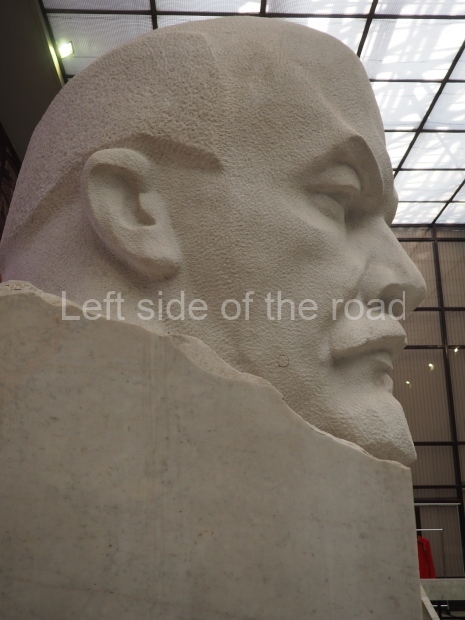

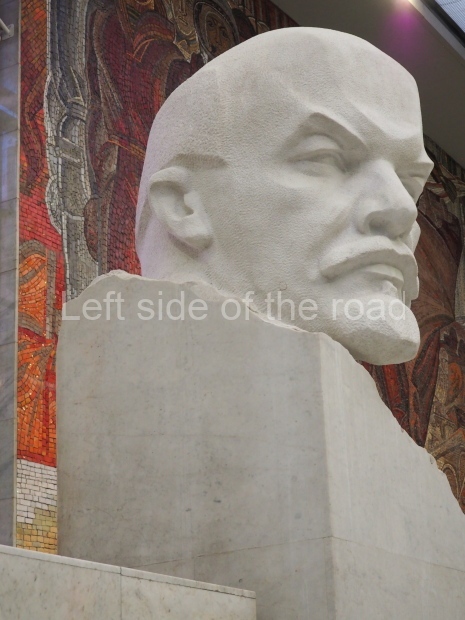

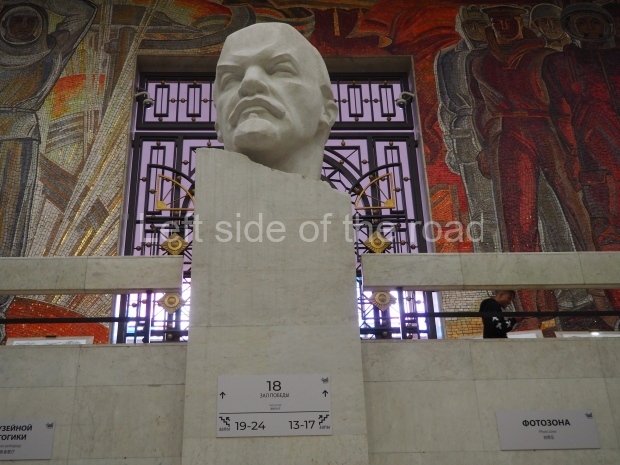

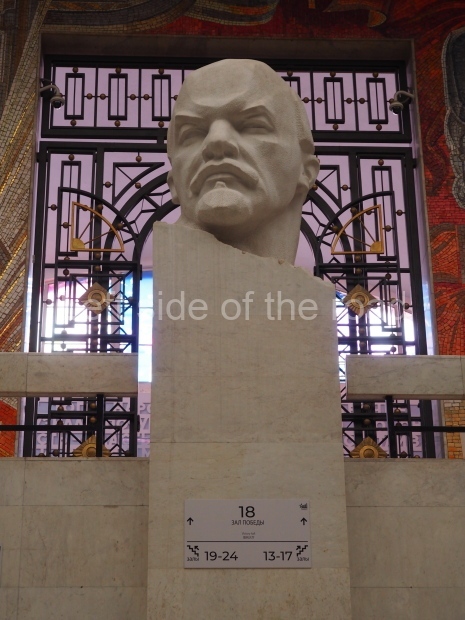

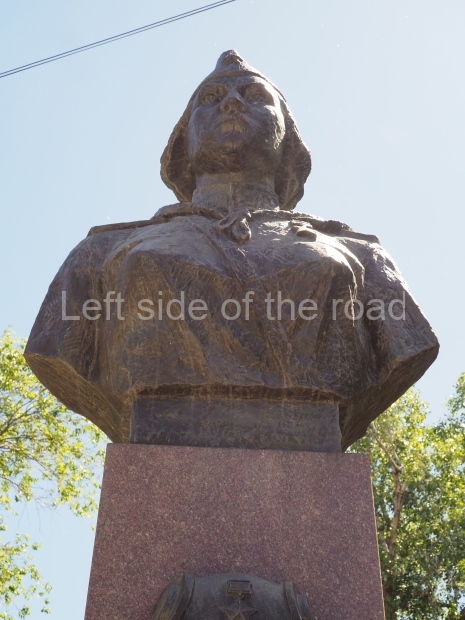

- the large bust of VI Lenin at the top of the stairs immediately facing the main entrance;

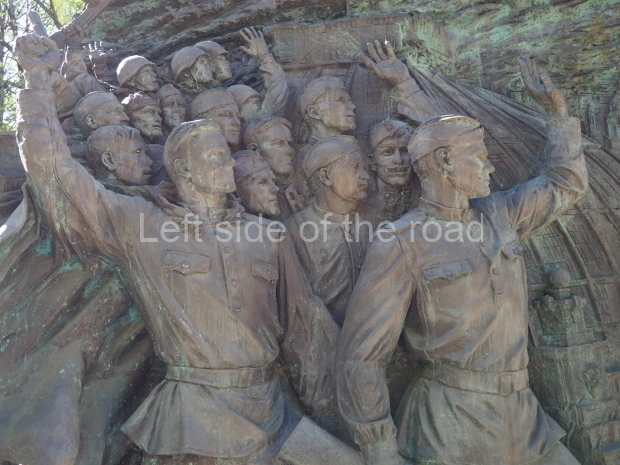

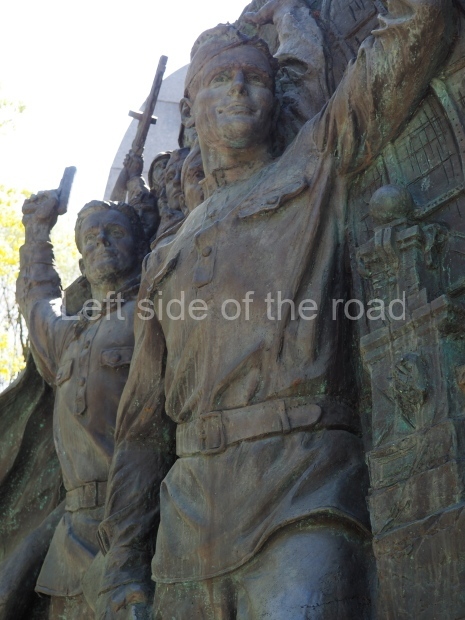

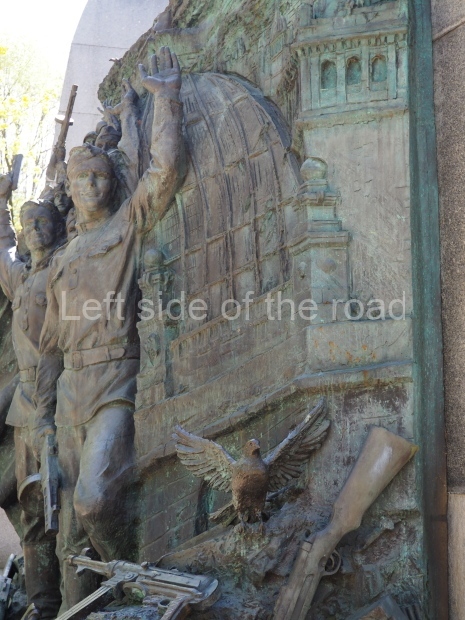

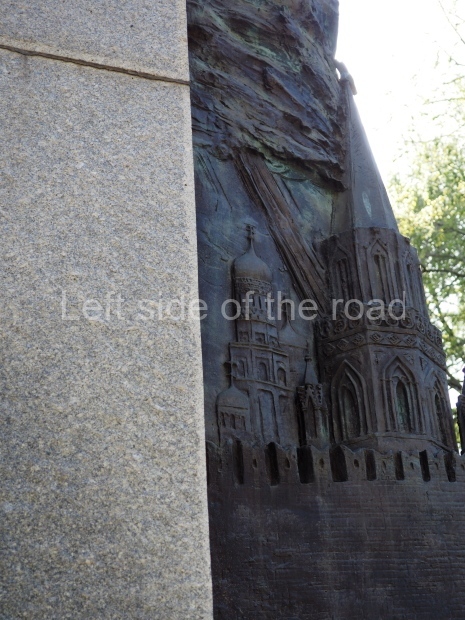

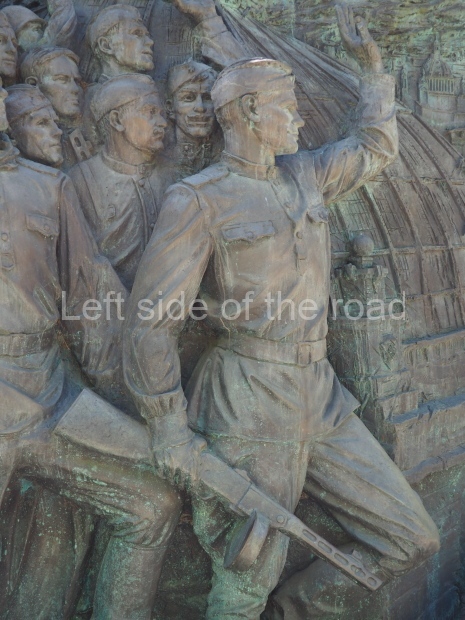

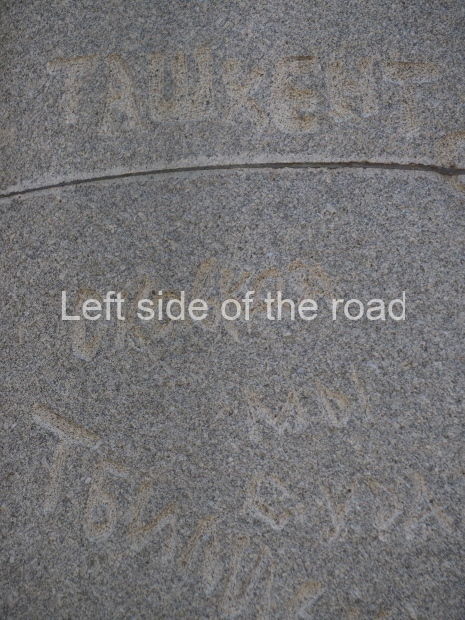

- the whole wall covering mosaic on the wall on the first floor landing – depicting on the right the struggle to maintain the Revolution during the civil war into the 1920s and on the other the Great Patriotic War and the defeat of German invading Nazism;

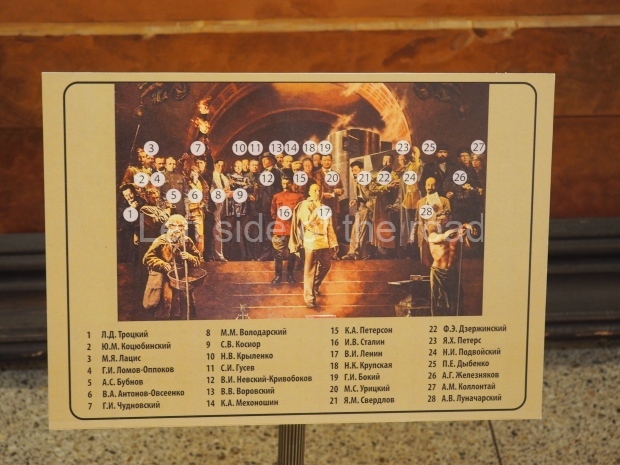

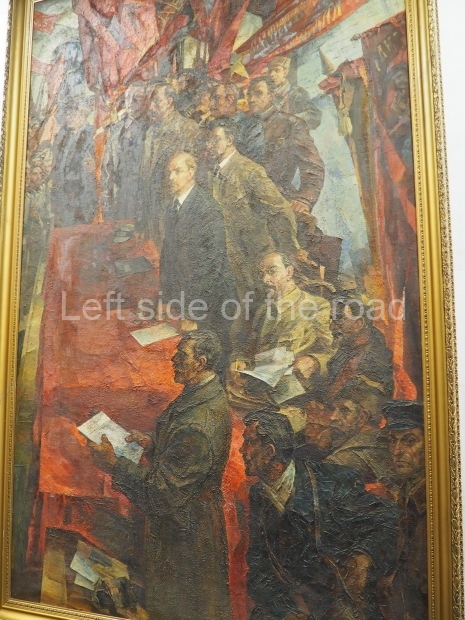

- the large painting in the second room (on the left had side on entering the room) which depicts the members of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party at the time of the October Revolution. This is an unusual way to present the individuals who were the leading cadres of the Revolution. I foolishly didn’t take note of the artist or when the painting was created but note Trotsky skulking at the extreme left hand side;

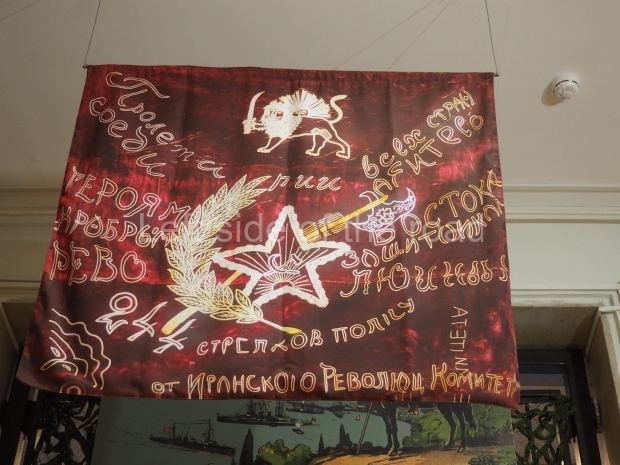

- the many banners, representing factories and places of work, of the volunteers who went to fight against the Whites and the fourteen, intervening imperialist powers;

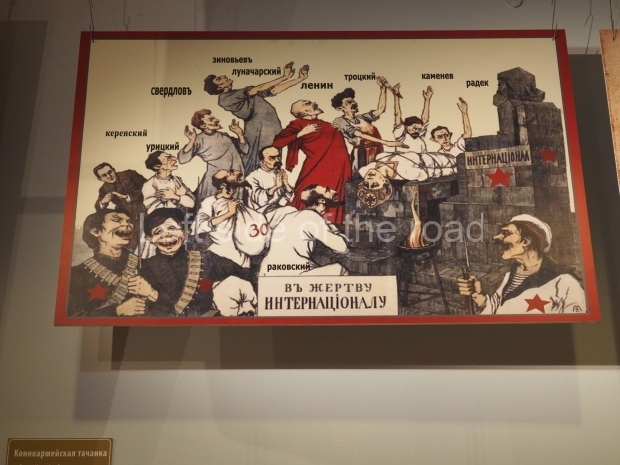

- the propaganda posters produced by both sides in the conflict;

- the machine gun fitted to the back of a horse drawn buggy;

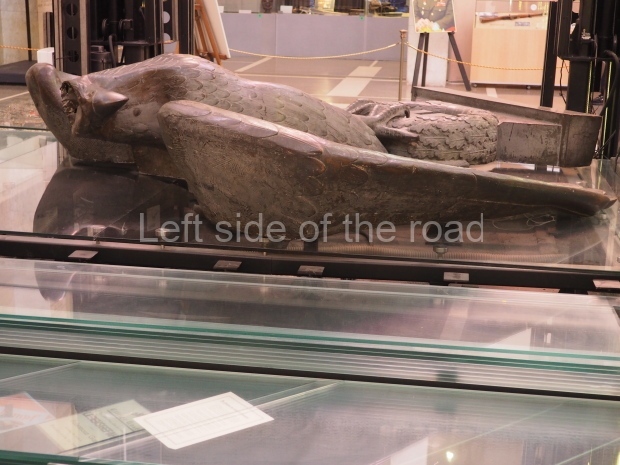

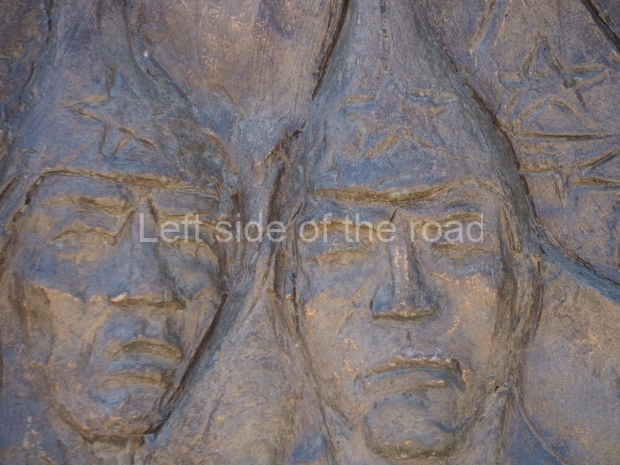

- the various sculptures demonstrating the unity of the workers and the peasants;

- the make-shift armoured vehicles;

- the multi-ethnic and multi-national extent of the revolutionary forces;

- the distinctive uniform of the first Red Army;

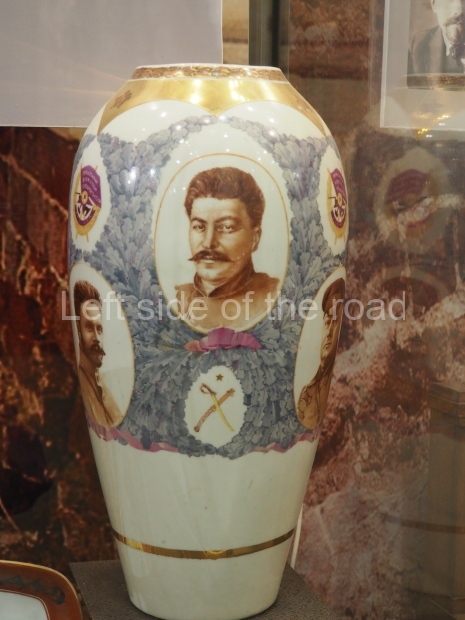

- the ceramic vase with an image of Joseph Stalin, Mikhail Frunze and other civil war military commanders;

- the huge, wooden fist with the words ‘пролстарский кулак врагм ссср’ which translates as ‘the proletarian kulak is an enemy of the USSR’;

- the images of VI Lenin and JV Stalin on the banners of the Great Patriotic War;

- the porcelain statue of an embrace and a kiss;

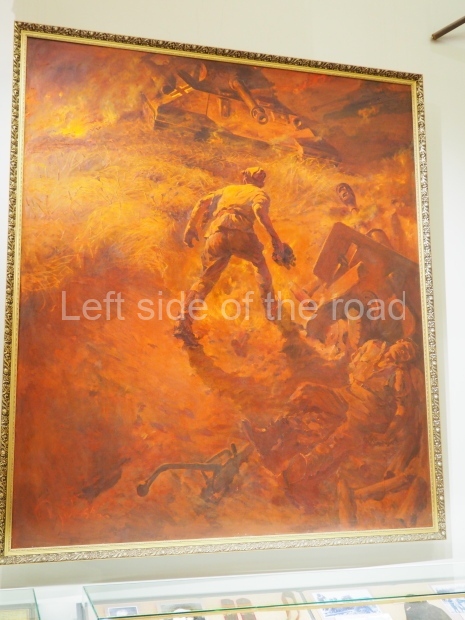

- images of heroism;

- ‘the battle in the rear’;

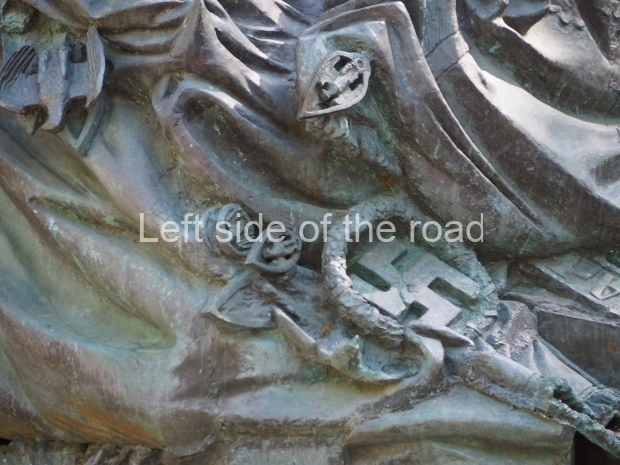

- the Nazi standards on the floor in the Victory Room;

- the Iron Crosses;

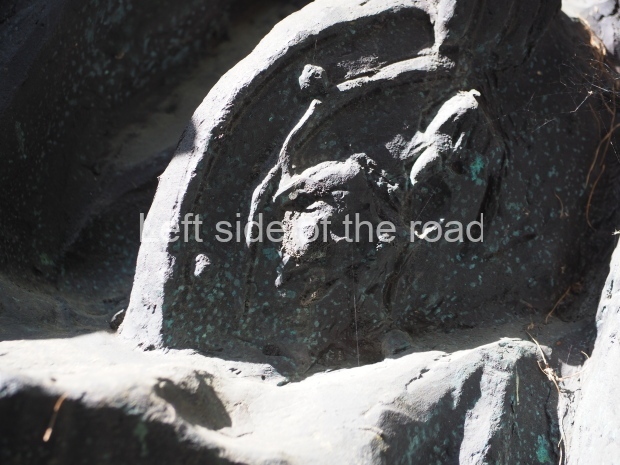

- the shattered eagle that used to stand on top of the Reichstag in Berlin;

- Hitler’s personal standard;

- the image of Marshal Zhukov riding his horse over the Nazi standards in Red Square on May 9th 1945;

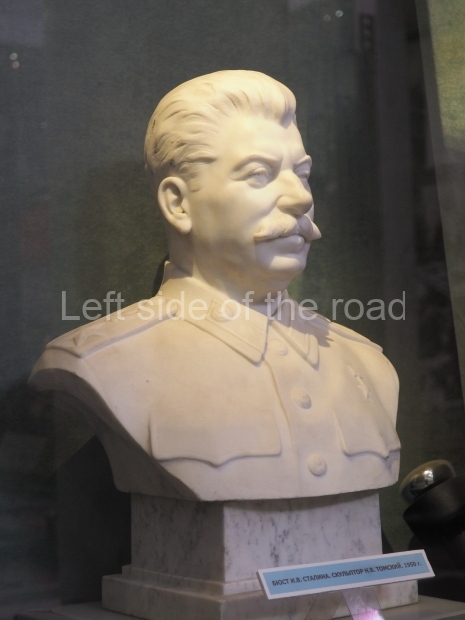

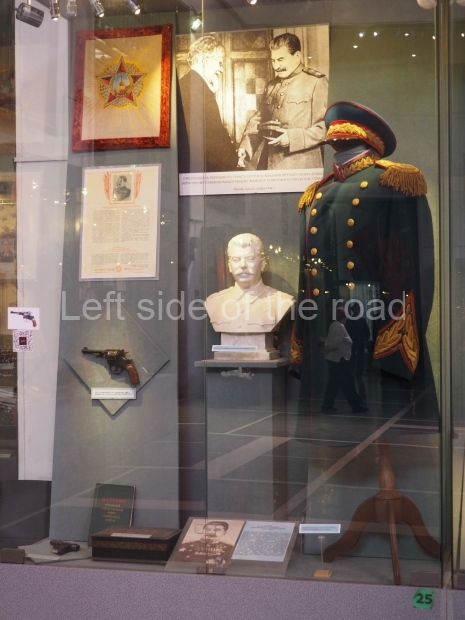

- the fine bust of JV Stalin, together with his military dress uniform;

- the shattered remains of the U2 American spy plane;

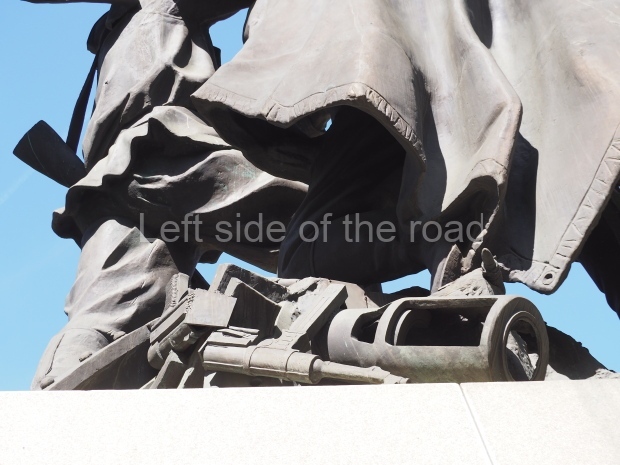

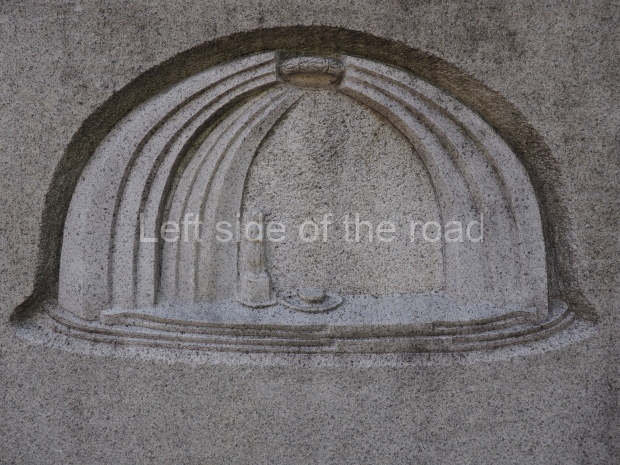

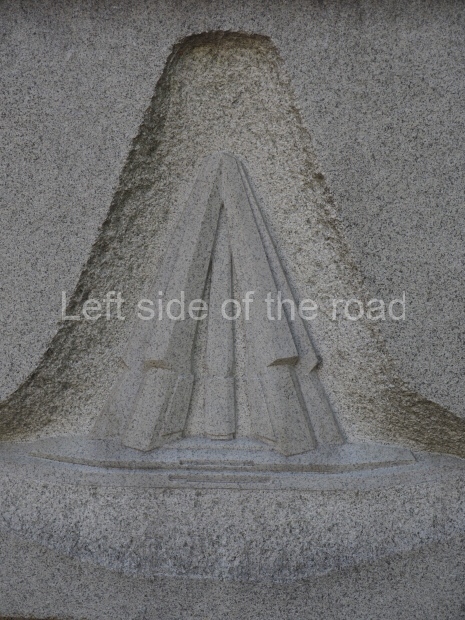

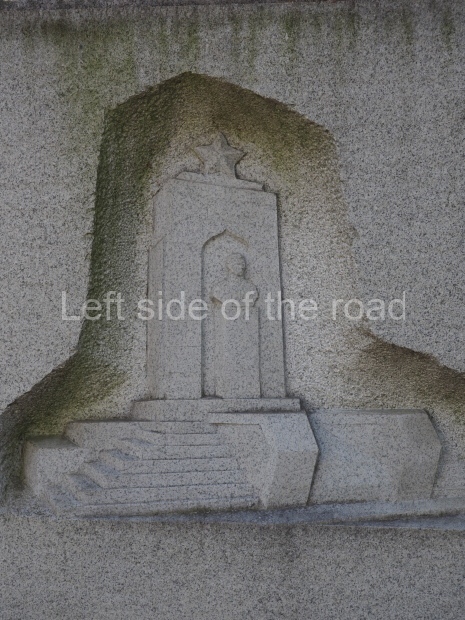

- the Red Army and and women flanking the main entrance to the museum;

among much more.

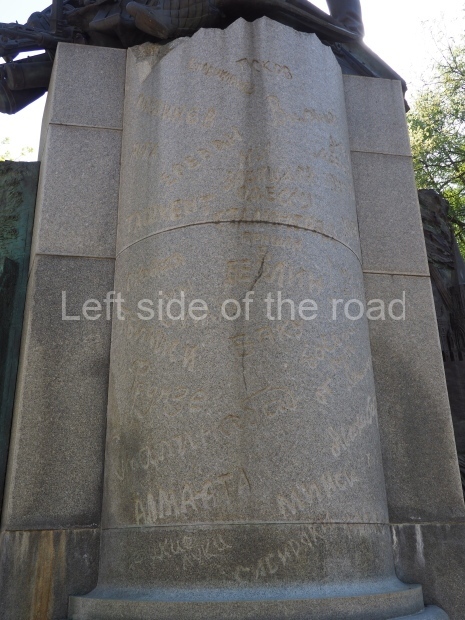

Location;

Soviet Army Street, Moscow

GPS;

55.78503 N

36.61708 E

How to get there;

The museum is a little over a five minute walk from the Dostoyevskaya Metro station on the Line 10 (Green). Leave by the exit that leads to the Red Army Theatre. Go past the right hand side of the theatre and at the road junction/pedestrian crossing take the right, once on the other side go left and the museum is about 100 metres on the right.