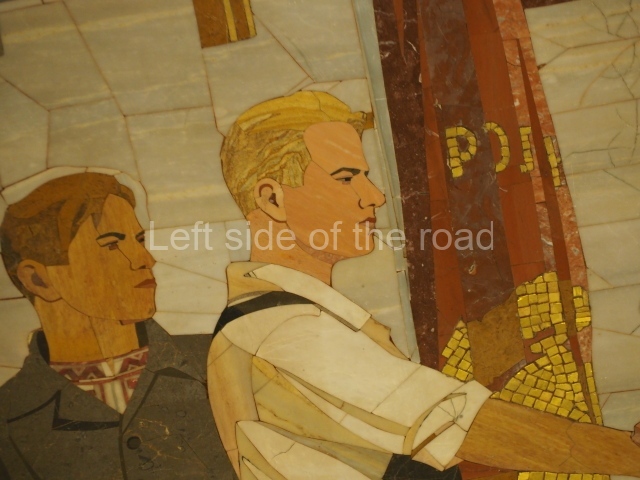

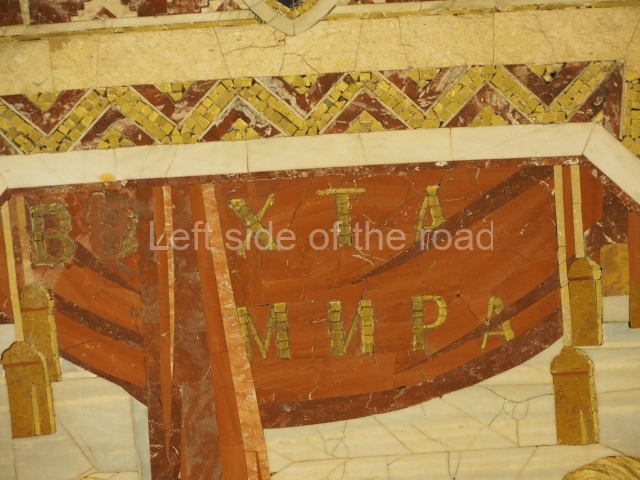

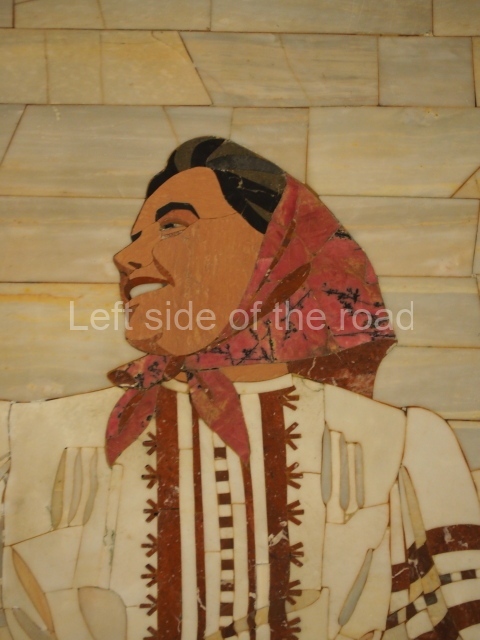

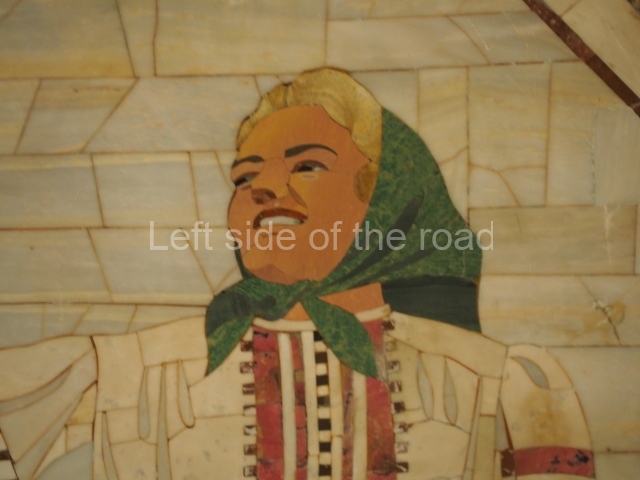

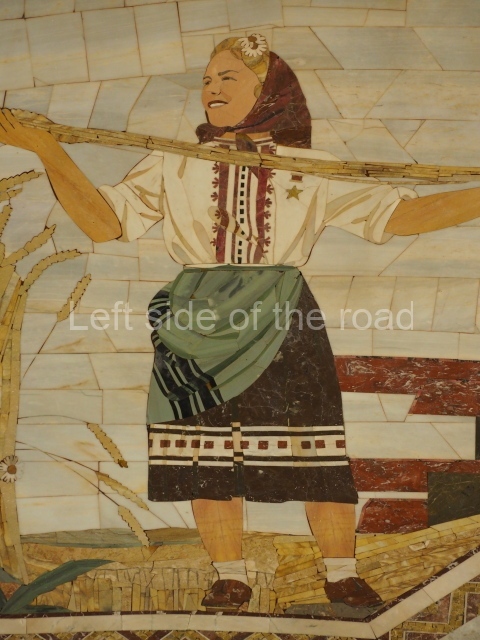

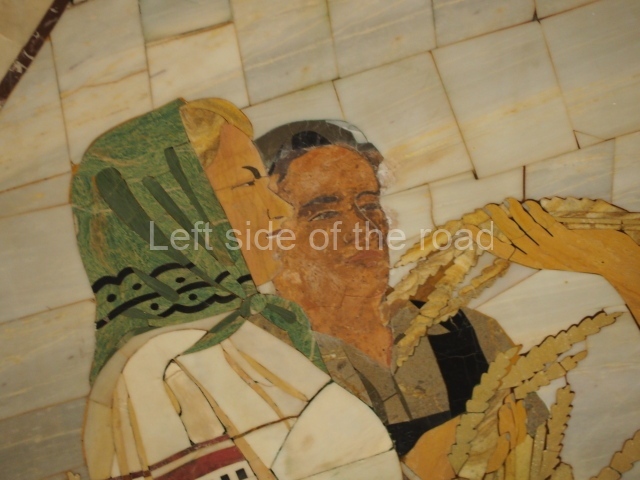

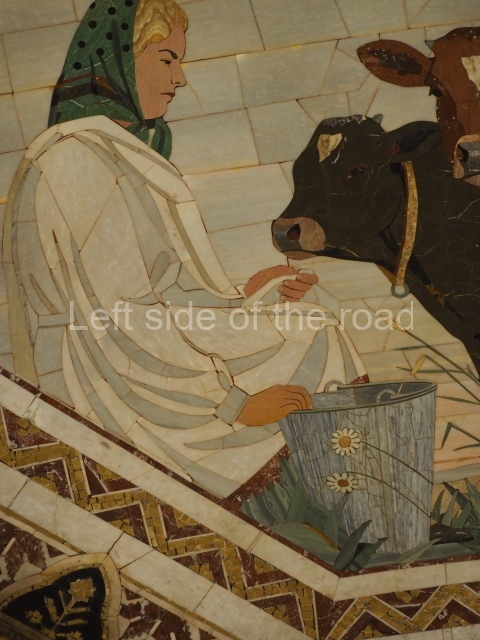

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery

Moscow Metro – Arbatskaya – Line 3

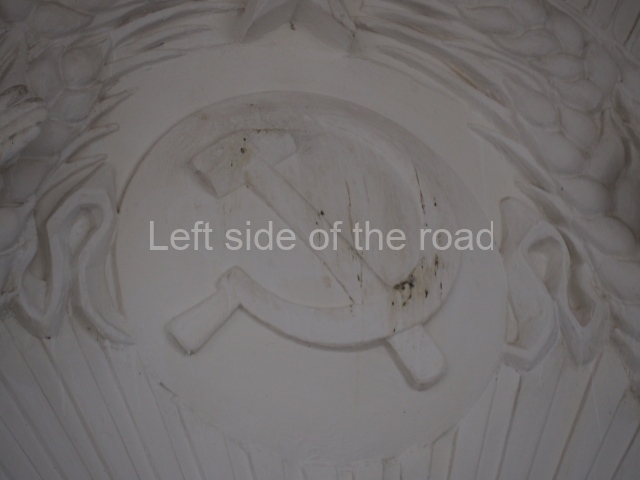

Arbatskaya (Арба́тская) is a station on the Arbatsko–Pokrovskaya line of the Moscow Metro. Along with Smolenskaya and Kievskaya, it was built in 1953 to replace an older, parallel section of track which has since become part of the Filyovskaya line. The old station had been damaged in a German bomb attack in 1941, so its replacement was much deeper and included larger stations that could double as shelters (especially in the event of nuclear attack). Although it was initially supposed to be closed permanently, the old section reopened five years later, creating the somewhat confusing situation of having two pairs of completely separate stations with the same names (Arbatskaya and Smolenskaya).

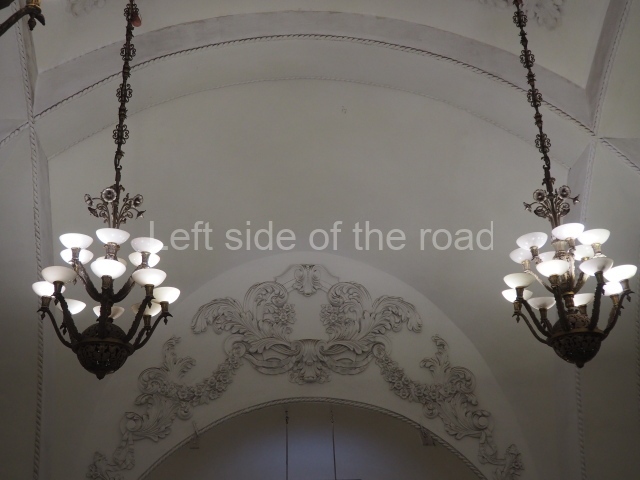

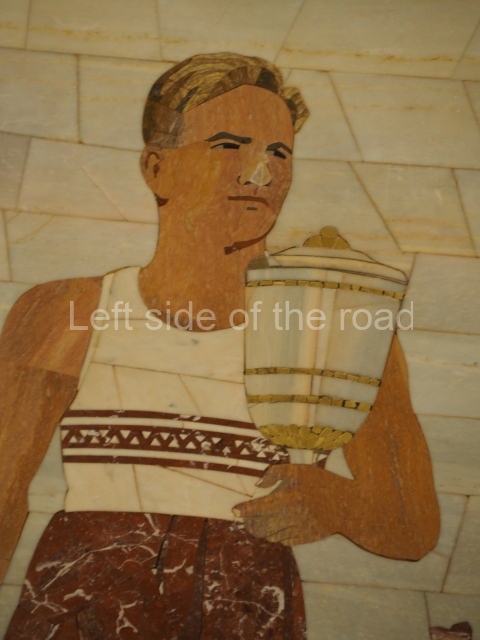

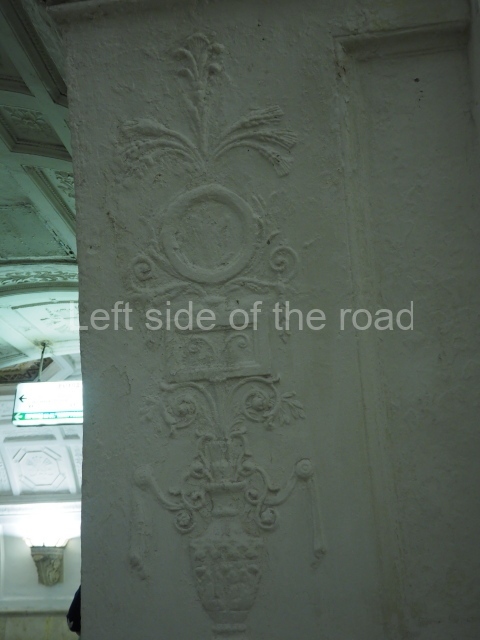

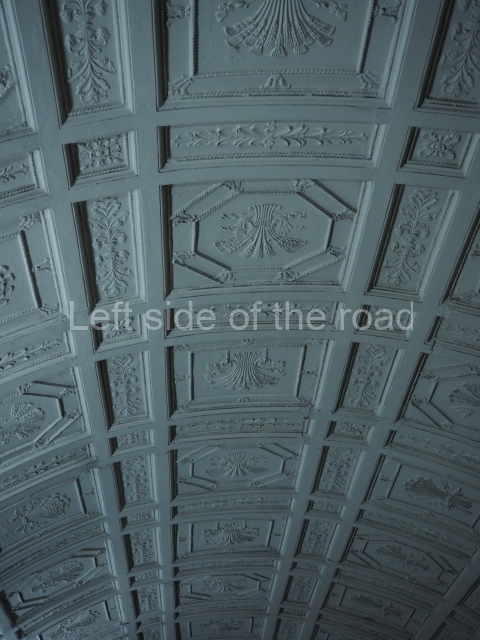

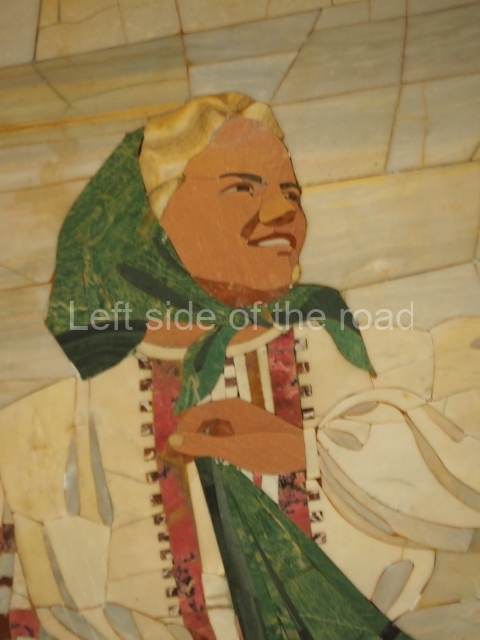

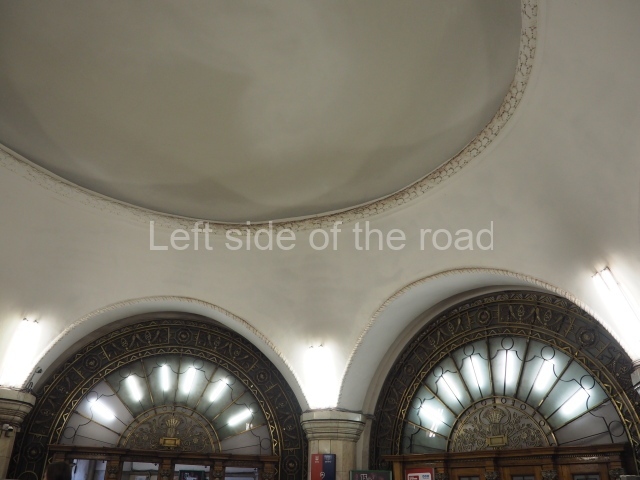

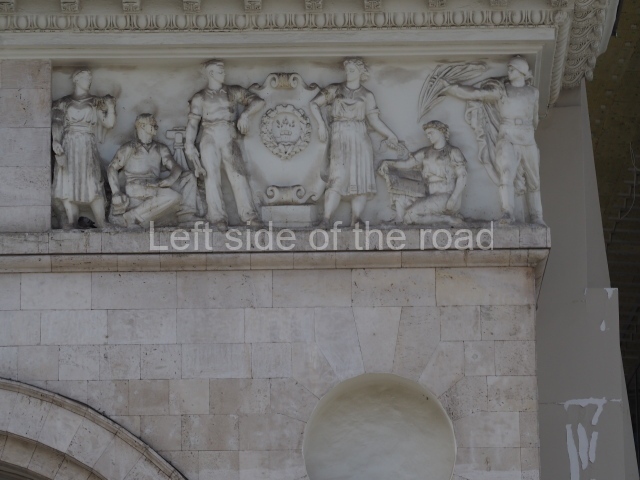

Arbatskaya was designed by Leonid Polyakov, Valentin Pelevin and Yury Zenkevich. Since it was meant to serve as a bomb shelter as well as a Metro station, Arbatskaya is both large (the 250-m platform is the second-longest in Moscow) and deep (41 m underground). The main tunnel is elliptical in cross-section, an unusual departure from the standard circular design. The station features low, square pylons faced with red marble and a high vaulted ceiling elaborately decorated with ornamental brackets, floral reliefs, and chandeliers.

Text from Wikipedia.

Arbatskaya, Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya Line

Date of opening;

5th March 1953

Construction of the station;

deep, pier, three-span

Architects of the underground part;

L. Polyakov, V. Pelevin, Yu. Zenkevich, A. Rogachev and M. Engelke

Transition to stations Borovitskaya, Biblioteka imeni Lenina and Alexandrovsky Sad

Arbatskaya is one of the largest stations of the Moscow Metro. It is 220 m long with passageways to escalators. Only station Vorobievy Gory is longer.

It has a specific architecture with pylons gradually widening upwards forming common parabolic vaults in the central hall and both track tunnels. This masks the closure of the volume typical of pylon stations. Moreover, the huge size of the central hall creates the feeling of simplicity and running perspective.

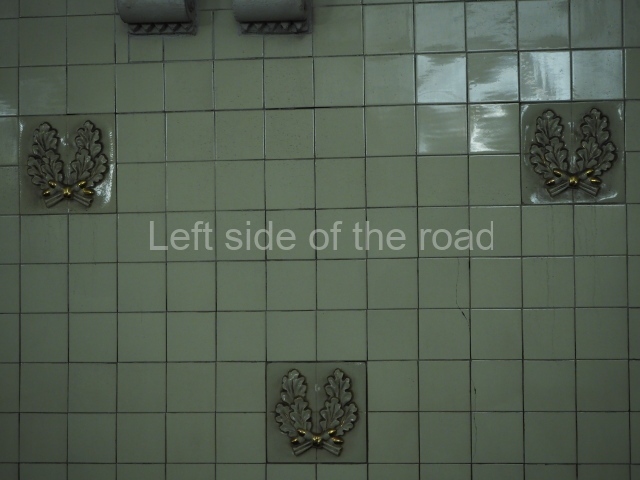

Arbatskaya has many constructive features similar to Ploshchad Revolutsii. It is also decorated with plastered surfaces (Attention! Do not lean against the walls when waiting for a train.) and low pedestals are faced with red marble. However when a train arrives to Arbatskaya from Ploshchad Revolutsii, a passenger seems to appear at the Age of Baroque from the Middle Ages. The bright white vaults, pylons, tunnel walls and ceilings of passageways and both entrance halls are adorned with alabaster mouldings as garlands, bouquets, clusters, aiguillettes, and tassels. The tunnel walls are covered with ceramic tiles, light lemon-coloured above and black at the bottom. The walls of the passageways and entrance halls are decorated with greyish-white marble above and red marble at the bottom. The station is illuminated with intricate baroque-like lamps in gilded bronze settings – two line of pendant chandeliers and sconces. A bench for three persons is near each pylon.

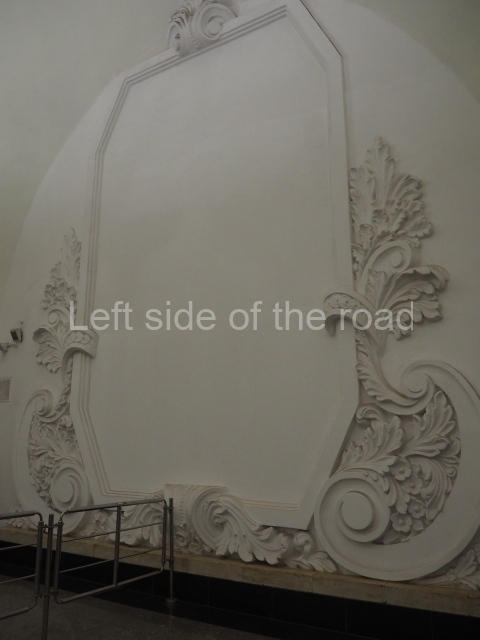

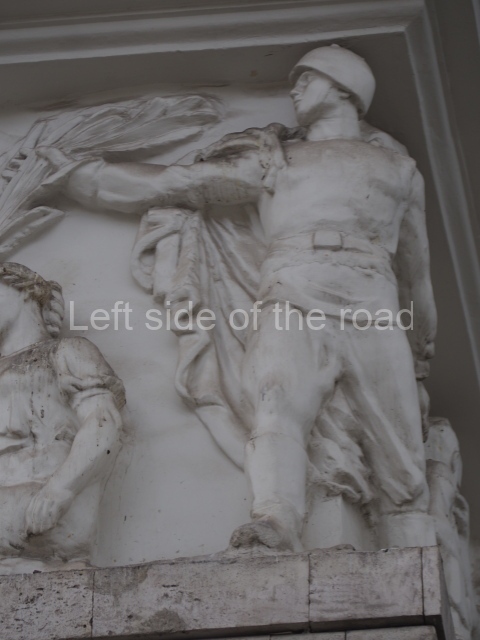

The exit to the city and transit to stations Aleksandrovsky Sad and Biblioteka imeni Lenina begin with an escalator at the eastern end of the station, which leads to the intermediate hall. A huge 26-branch circle chandelier is attached by chains to the ceiling. The other exit to the western ground hall leads to the western end of Arbatskaya. The long escalator runs to the rectangular hall. There is a huge vertical panel – white on the white wall rounded with baguette-like moulding opposite the escalators. There was a main full length portrait of Generalissimo Stalin with all his regalia. Nowadays it is covered with whitewashed decorative plates. The portrait was the only element of the station’s decorations which somehow reminded [sic] about the War. Such ‘warlike character’ distinguishes Arbatskaya from most other stations of the late 1940’s – early 1950’s.

Text from Moscow Metro 1935-2005, p62.

There are two cafeterias in the Moscow metro: one at metro Arbatskaya and another at metro Voikovskaya. [I didn’t know this at the time of my visit – so no food reviews.]

The canteen at Arbatskaya has been open for 30 years with the other one in operation since 2000. Initially these cafeterias were founded with metro employees in mind, but now they are open to the public who can enjoy a quick meal on their way to work. They are quite cheap and passengers are often surprised by the good quality of the food.

The house specialities are belyashs (fried pastry stuffed with meat) and hot dogs, but the menu also includes more sophisticated fare, such as chicken with pineapple.

Text from Russia Beyond.

Location:

GPS:

55.7522°N

37.6061°E

Opened:

5 April 1953

Depth:

41 metres (135 ft)