More on the Republic of Georgia

Spa Resort, Tskaltubo, Georgia

Tskaltubo’s a strange place. The village itself is, to say the least, nondescript and if it had any purpose at all in the past it was to serve the resort hotels and spa complexes which were built on top of the hot springs and the (foul-smelling) curative mud.

All the hotels and spas are either close to or inside a huge park that is (very roughly) 2 kilometres long and about 500 metres wide (at it’s greatest) with a north-south orientation. When this place was at its busiest there must have been thousands of people here and would have resembled the holiday resorts on the Costas in Spain. Walking around the, now mostly abandoned, hotels you come across corridors going off corridors with rooms on either side. Although all of them have large restaurants they would have been unable to cope with all the residents at the same time so there must have been a very strict and organised rota at meal times.

In a previous post, Tskaltubo’s abandoned Spas, Springs and Sanatoria, I attempted to give the background of this area and a feeling of the abandoned faculties which would have had many happy memories, I’m sure, for thousands of Soviet citizens.

Information is somewhat contradictory but what is almost certain is that the heyday of the area would have been from the 1960s to the end of the 1980s – and I imagine the crash would have been as sudden as the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991. The whole infrastructure which would have moved so many people back and forth from the Soviet Union to Georgia would have fallen apart; the people had too much of an uncertain future to consider going on holiday; money quickly became scarce; and Georgian nationalists would not have been that welcoming when they saw the weakness of the once powerful Socialist entity.

But if citizens from the rest of the Soviet Union lost a favoured holiday destination the Georgians didn’t benefit. Many of them would have lost their jobs overnight. And this wouldn’t have been just those who worked directly in contact with the visitors in the hotels and the spa complexes. A whole host of ancillary jobs would have gone as well in the greater Kutaisi area.

For example, there used to be a railway station (close to which is now the Tourist Information Office) and at the bottom of the park, on the exit road leading to Kutaisi, there was a not insignificant hospital. The latter would have served not only the visitors (with so many statistically there would have been a number of accidents and emergencies) but those locals who worked in the resort, many of whom I imagine lived in the apartment blocks and houses to the east of the main road to Kutaisi.

Recently there’s been renovation of some of the spas (especially Spring No. 6, which houses Stalin’s ‘private bath house’) but many of the accommodation blocks have been (partly) taken over by refugees from Abkhazia, who are living in disgusting slums. Although I’m sure that few in the Georgian government care about these refugees they will probably be ‘safe’ in their squatter status as there’s no way that the area will ever return to it’s illustrious past and there will never be enough money to return all the resort hotels to their former glory.

However, there has been major investment to restore (at least in part) probably one of the biggest hotels, if not in the number of bedrooms at least with its surrounding grounds. This is now called the Legends Spa Resort and is located to the east of the park, half way from the entrance to the resort area on the way to the village of Tskaltubo.

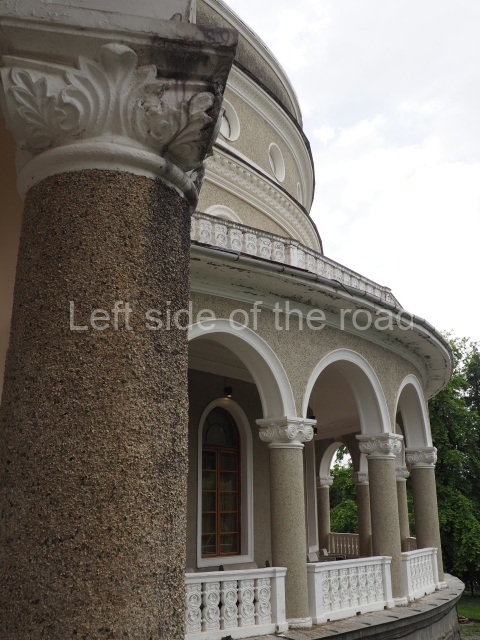

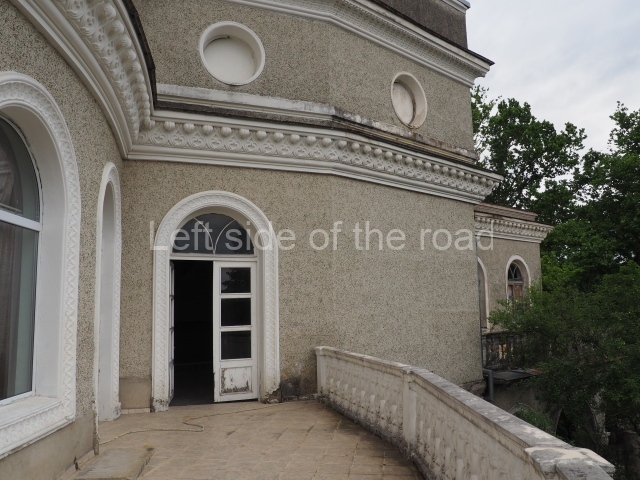

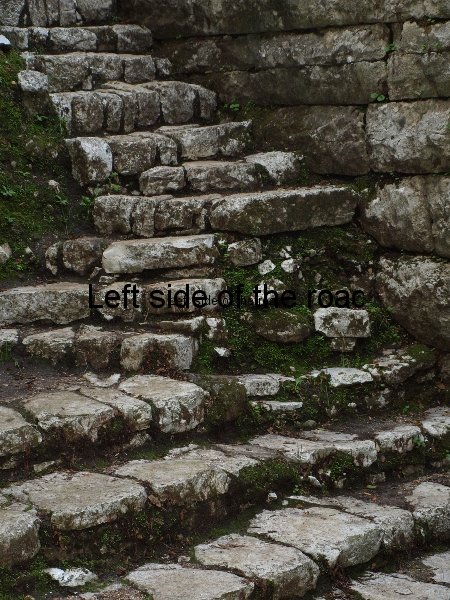

At the height of its popularity this must have been one of the most impressive complexes in the area. The three accommodation buildings of the complex are set along its own private road, quite high above the public road that passes on the way to the village of Tskaltubo, and is reached via two portico entrances from which wide steps lead up to a viewpoint. The trees here are now very much established but forty or so years ago, from these vantage points, the visitors would have been able to look across to the park and a walk from the hotel to the park, or even the spas, would have been a common activity for the visitors.

Although in its prime there would have been on site spa/health facilities these have still yet to be completed (if ever) and those present day visitors on an accommodation and health package get bussed to one of the restored spas in the area of the park, a few minutes away.

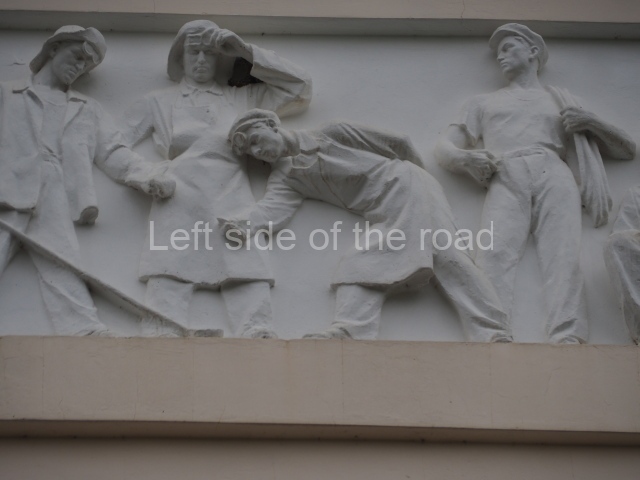

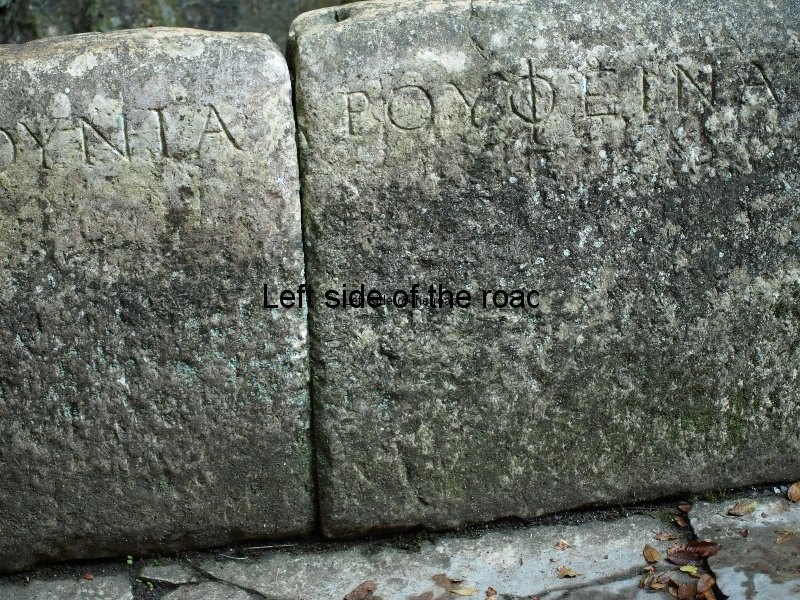

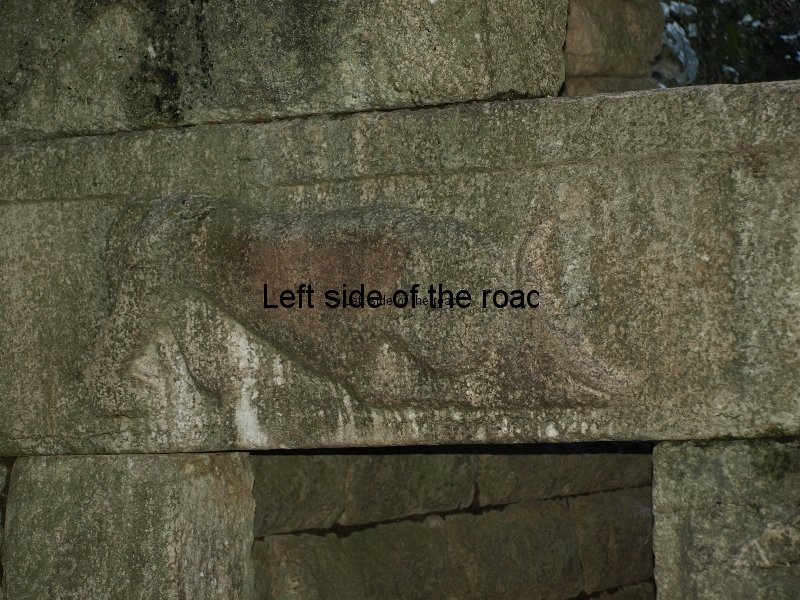

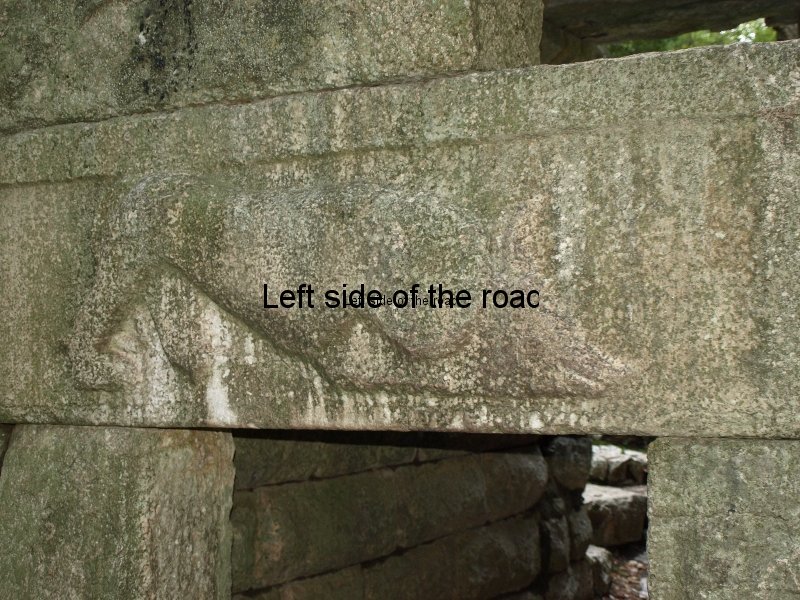

Of the three buildings only one has had any substantial work carried out to bring it up to present day standards (and expectations) to open as a hotel – and that only partially – and is the only building currently in use. This is the northern most of the three which has an interesting Socialist Realist bas relief frieze above the front door. I’ve read various articles suggesting that the renovation of the rest of this building is some time in the distant future.

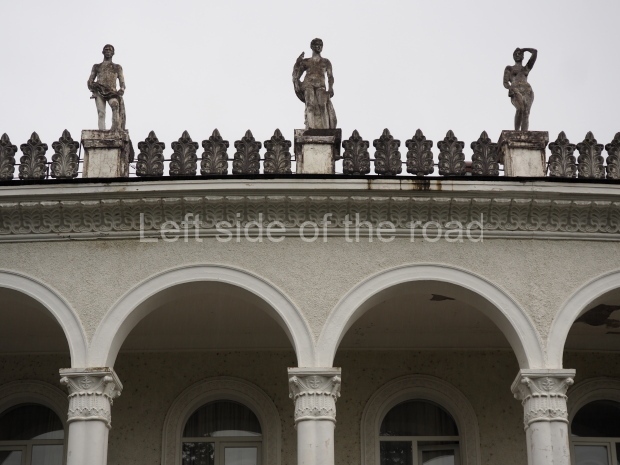

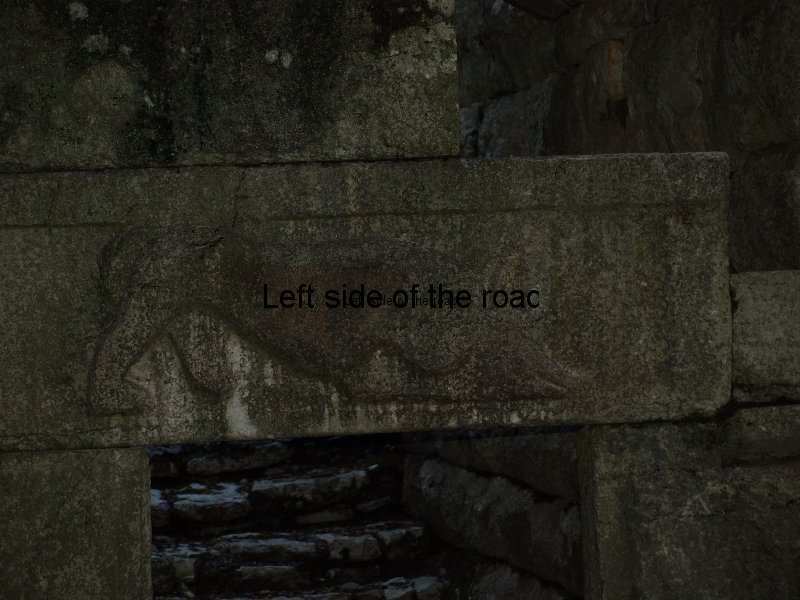

One of the other two buildings (the one with statues above the main entrance) appears to have had some work carried out in the relatively recent past, although it definitely looked like a budget option – but this looks as if it hasn’t been used for some time. The third looked as if it had not been touched at all since the last Soviet visitor left and although not in the best of condition – and difficult to see clearly due to the sprawling vegetation – it also has a Socialist Realist frieze on the façade.

Only very few people were staying there when I visited at the very beginning of June 2024 but I got the impression that large groups would arrive from time to time so perhaps my stay wasn’t indicative of the occupation levels – and anyway it was still relatively early in the summer season.

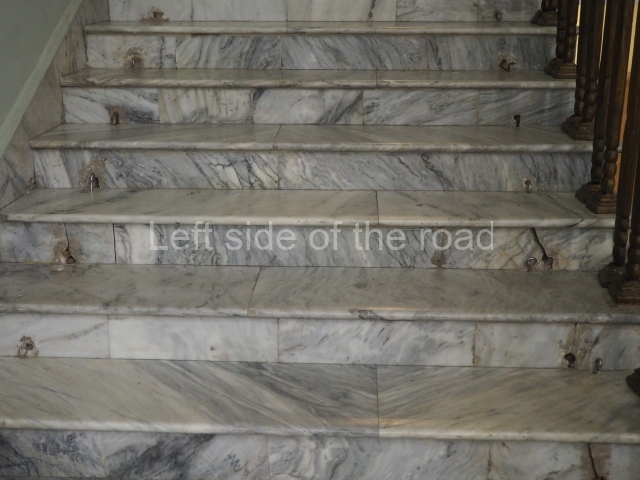

Having walked around derelict and completely uninhabitable (although some people are forced to live there as they have nowhere else) ex-hotel buildings in other parts of Tskaltubo it was interesting to see what these places were like when they were such a popular destination for Soviet workers. But, as stated above, not all of this particular hotel has been fully restored – so dereliction was only just (literally) around the corner. Go up one staircase and everything is what you would expect in such a hotel but go up another and you see what a lot of work is needed to bring the whole building up to scratch.

A picture paints a thousand words so it is hoped that the slide show will provide a better idea of the whole of the complex. Here I just want to point out a few aspects which stuck out in my mind as I explored all the (sometimes) dark and dusty corridors. For someone who wants to get an idea of the place the fact that there was no restriction on where you could go was quite refreshing, so-called ‘health and safety’ – often used as an excuse to prohibit access – gone mad certainly in the UK (if not other countries in Western Europe).

In no particular order;

- the many rooms which had been renovated but not kept immediately ready for guests but would be sorted very rapidly if a big group was to book in;

- the stacks of old spa baths, very dated in their design, which had been taken out of the hotel’s own spa area but the new baths had not yet (in the summer of 2024) been fully plumbed in and the work to do so seemingly frozen for whatever reason;

- the covered walkway, with metal-framed windows on either side, now (and probably originally) lines with potted plants that joined the accommodation area with the dining and entertainment area of the complex;

- the large circular dining room which wasn’t in use when I was there but looking as if it wouldn’t take too much to get it ready;

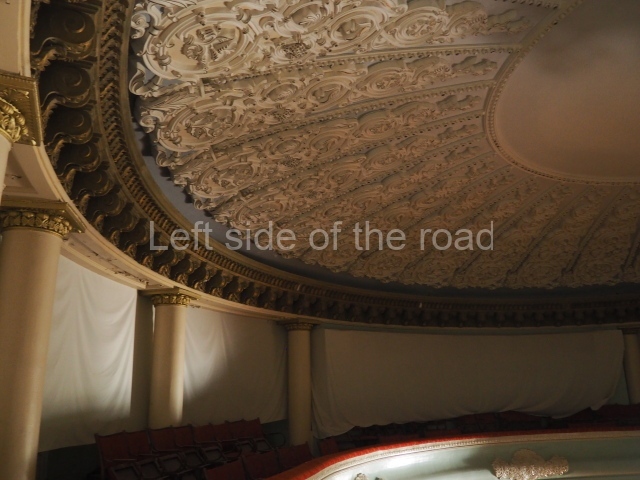

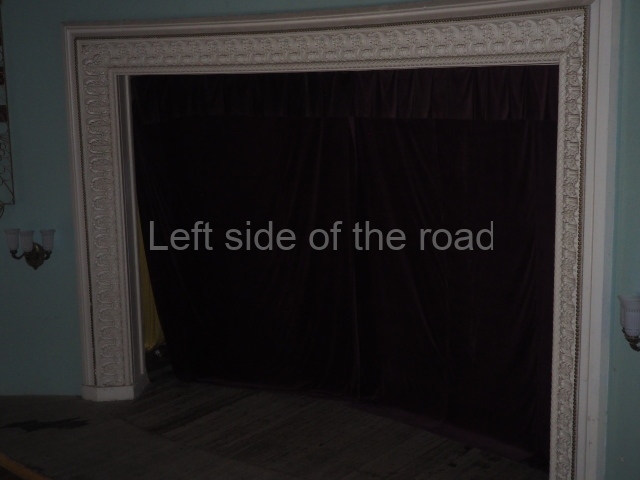

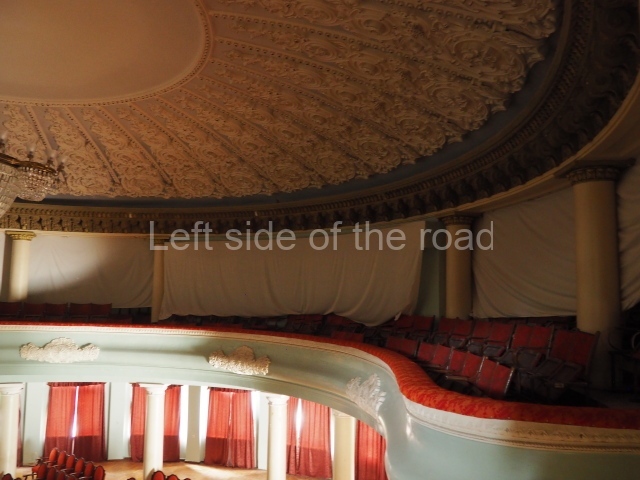

- the circular cinema/theatre which downstairs looked as if it could be ready for a performance at any time but in the balcony the chairs were dirty and many of them broken or missing with the walls flaking;

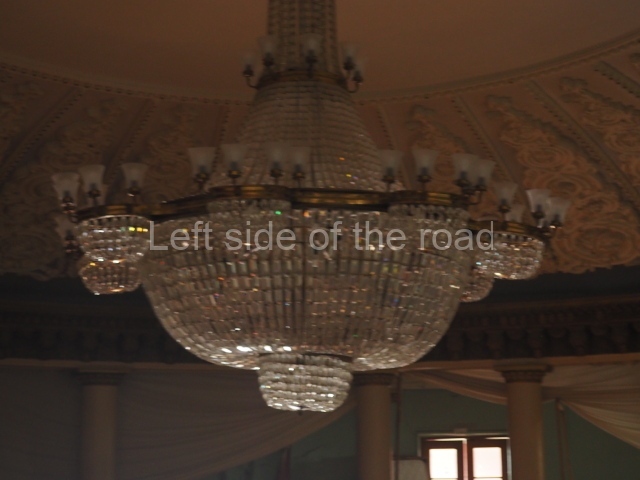

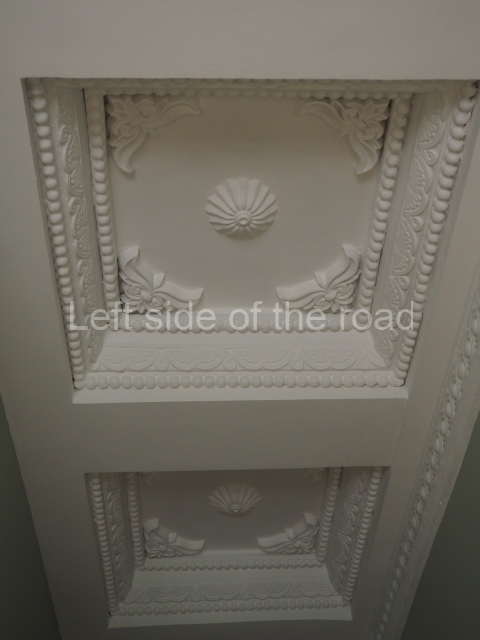

- the light fittings that were very reminiscent of the Moscow Metro. Whereas western metros and underground systems are industrial spaces that of the Soviet transport system was ‘domestic’, there being light fittings that you would find in other public buildings in the country, which included chandeliers, all which provides a softer lighting as opposed to the harsh, functional fluorescent strips which are the norm in the west;

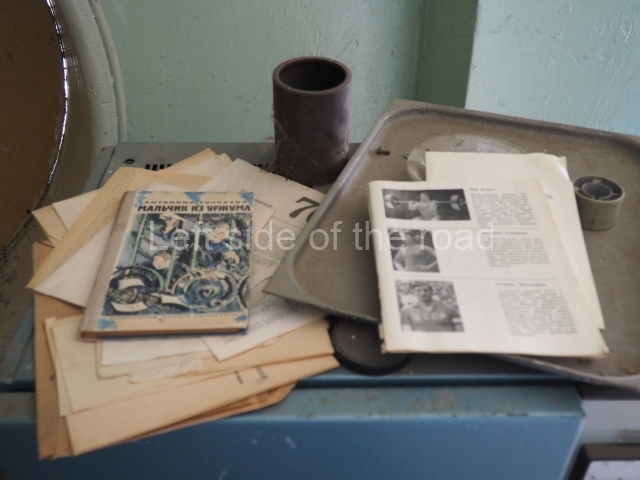

- the cinema projection room which still houses two, late 20th century 35mm projectors, one of which still had a reel of film in place. Although not very tidy and with a few things having been taken for use elsewhere you could still imagine (with a fair stretch of the imagination) that a film could be shown tonight;

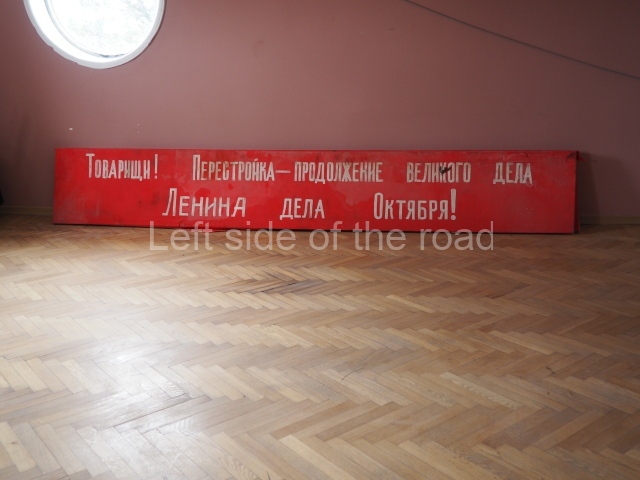

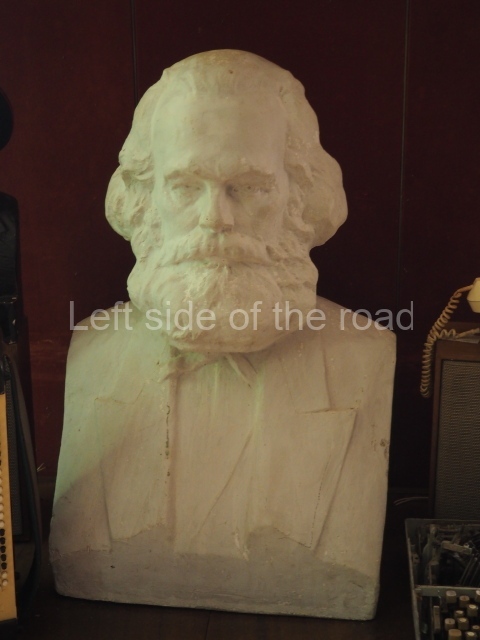

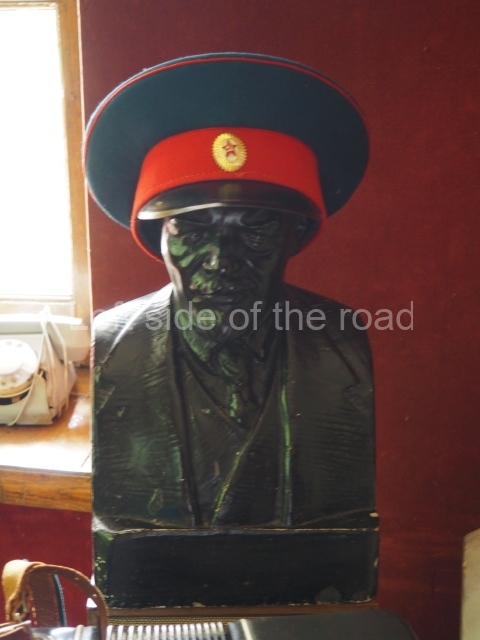

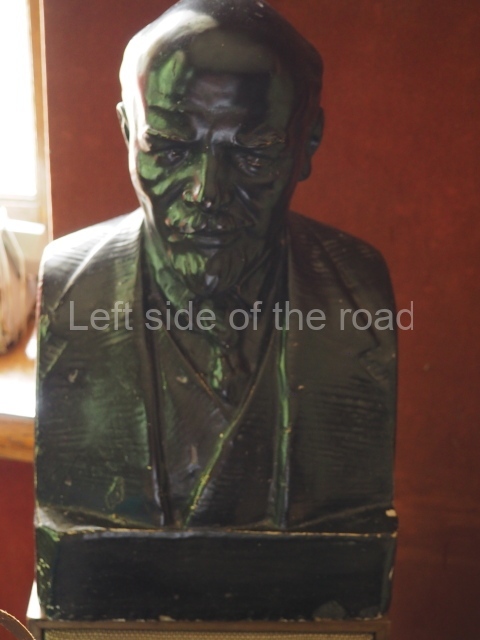

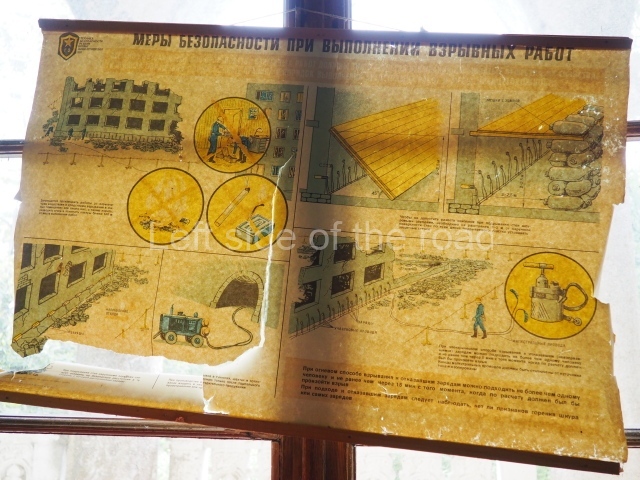

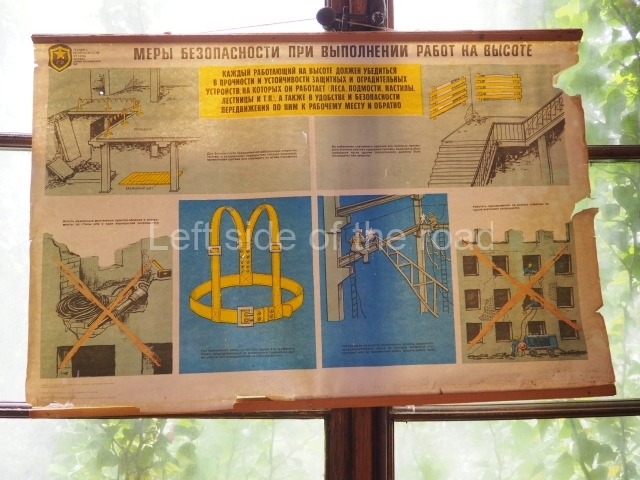

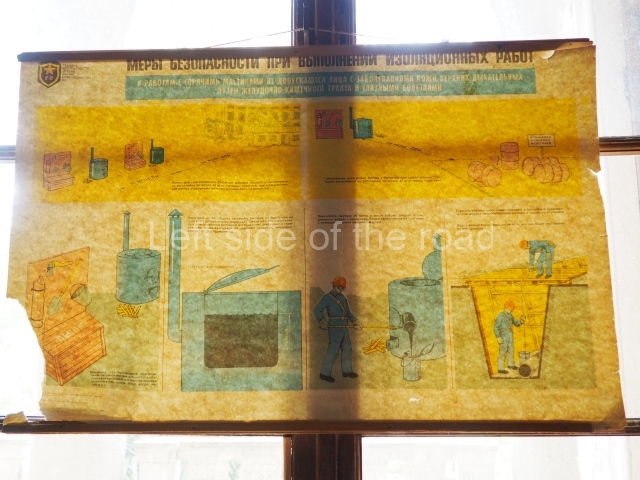

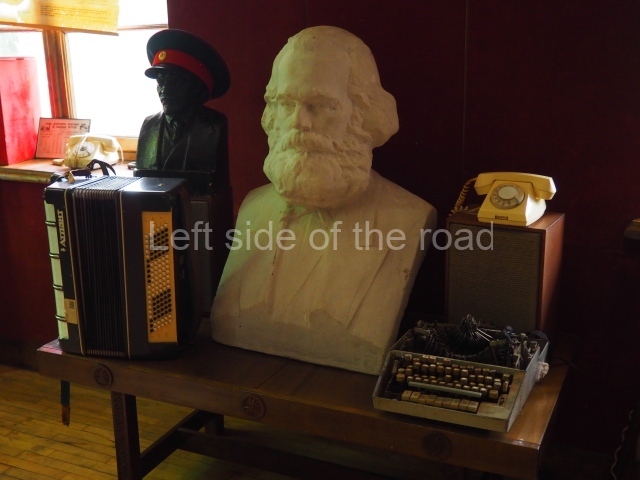

- the ‘museum’ – which is really only a higgledy-piggledy collection of items which no one could find a present day use for but didn’t want to throw them in the skip. This includes a bust of Karl Marx and one of VI Lenin, as well as some old health awareness posters and a 1980s ‘sound system’ amongst other nick-knacks. This all in what was a small café/bar in the latter days of the Soviet resort;

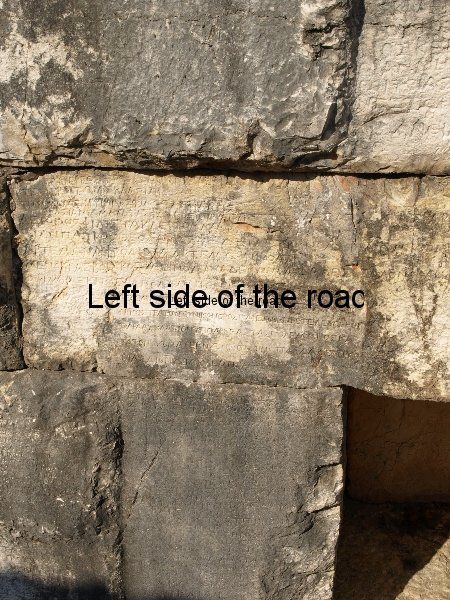

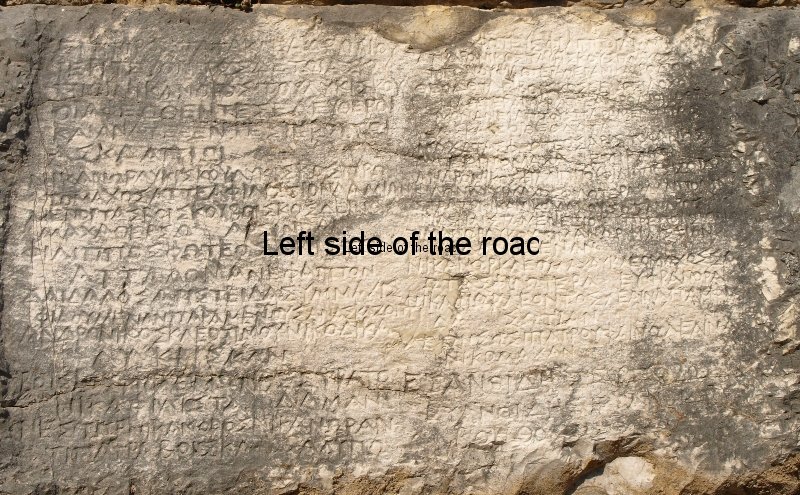

- a frieze depicting industrial workers and those in working in the countryside, as well as ‘intellectuals’ necessary for the construction of Socialism – the workers of hand and brain. The frieze above the entrance of the first building – that which is in constant use – in a very good, and restored, condition. The one over building three – the building that doesn’t seemed to have received any renovation of any kind since the building was closed – needing a bit of loving care but still in a good enough condition that you can make out the story;

- remnants of the 1980s in terms of furniture, curtains, pianos, light fittings, etc. All the renovation seems to have attempted to recreate the ambiance of the past where possible;

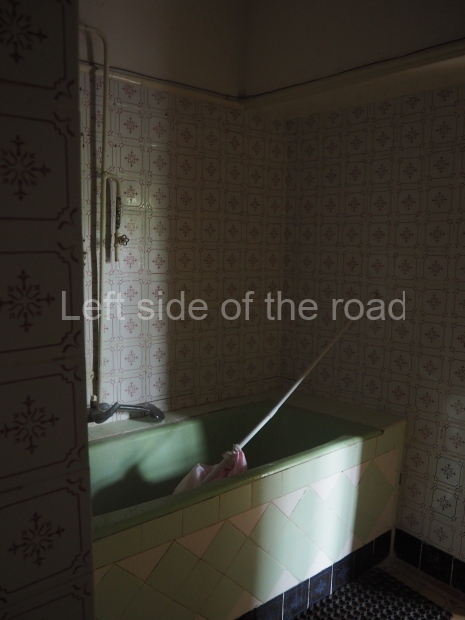

- ‘Stalin’s suite’ – which is located on the first floor of the third (the least ‘luxurious’) building. As stated above there doesn’t seem to have been any work carried out in this building and for that reason is the most derelict. That is, apart from a small area on the first floor on the west side of the building. This is a small suite comprising of; a sitting room; a bedroom; a small office and a bathroom. Obviously Uncle Joe wasn’t into cooking as there are no facilities for such. This is said to have been Stalin’s residence of choice. Now whether this is true or not I cannot say. I’ve also read about a villa on the other side of the park that Stalin was supposed to have used when visiting Tskaltubo. But if we assume that it is true then what this demonstrates is how humble and undemanding a personage Comrade Stalin was. NO capitalist leader at the same time that he was the leader of the Soviet Union would have stayed in such humble circumstances – even less so now. And as with his ‘private bath house’ in Spring No. 6 it just goes to show what an unassuming man he was – a true leader of the working class.

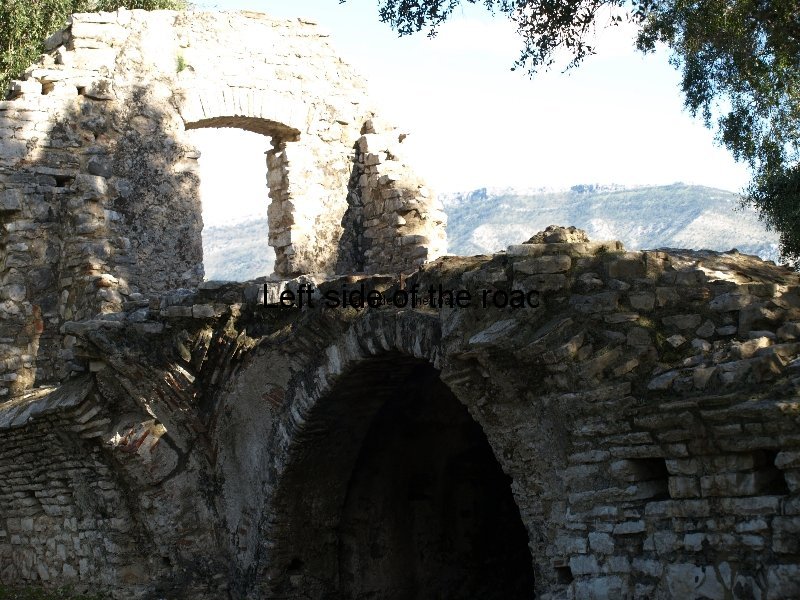

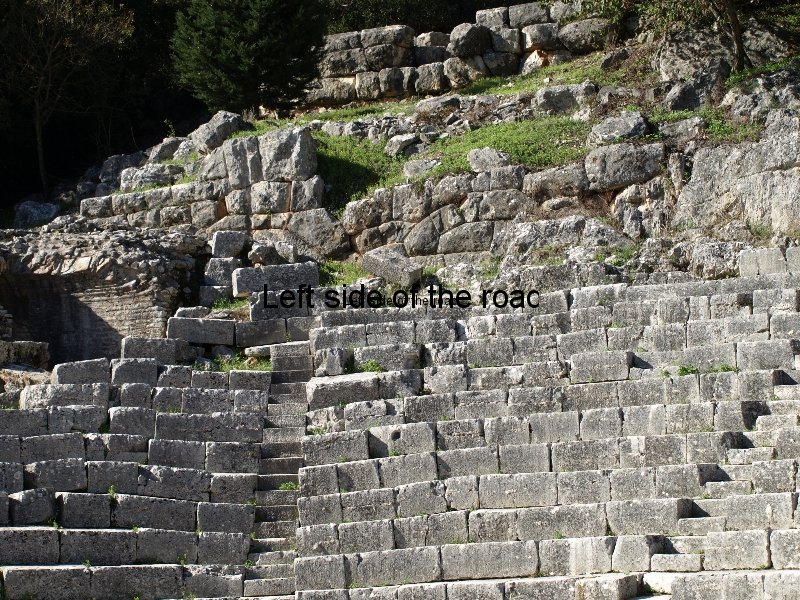

Another thought I had when walking around this complex just reinforced what I was thinking when I first visited Tskaltubo. Yes, many of the buildings, both the hotels and hot springs/spas are ruins but that was due to neglect and not mindless vandalism. In various parts of this complex you get the impression that one day everyone just up and left – some being careless and not shutting the doors or windows. Come the winter or the rainy season the elements stared to make an impact and some of the wooden parquet floors were damaged. As there was no regular maintenance being carried out that meant that, over time, water started to get in through breaks in gutters or leaks in roofs thereby causing damage to ceilings and walls and wooden window frames started to rot. Lack of regular maintenance also meant that the exterior stonework started to stain and crumble.

Although there must have been some element of looting it wasn’t complete and although it might have caused long lasting damage in some circumstances it certainly wasn’t general. This was very different from what happened when things fell apart in Albania. In that country there was wholesale destruction and whereas, at least, some of the buildings in Tskaltubo could be brought back into use you can say that about remarkably few in Albania.

Whether by commission or omission I still feel that the people’s of the once Socialist Republics ended up throwing out the baby with the bath water.

Location;

Rustaveli St 23, Tskaltubo

GPS;

42.321194º N

42.604205º E