The Roman City of Baetulo, Badalona Museum

I’d think I’d be fairly safe in saying that the overwhelming majority of people who visit Barcelona aren’t there for what remains from the Roman period – many not being aware that the Romans had actually been there in the first place – most coming to view the Modernist architecture of the likes of Antonio Gaudí and Lluís Domenech i Montaner. That’s a shame as the city has remnants from 2,000 years ago, although admittedly some of them need to be searched out. Even fewer people would be aware that just a few kilometres down the Metro line to the north-east of Barcino (the Roman name for Barcelona) is the Roman City of Baetulo at Badalona Museum, one of the most important Roman archaeological sites in Catalonia.

Baetulo dates back to the early part of the first century BC (or BCE, as it is sometimes referred) and was one of the first Roman settlements to be established in the Iberian Peninsular. Later there would be a whole line of these along the coastal road that would go as far south as Andalusia, passing by Baleo Claudio (for the salted tuna and garum) just south of Cadiz on the Atlantic coast, up to Italica, at present day Santponce, just across the Cuadalquivir from Seville, the virtual bread basket of the Roman Empire.

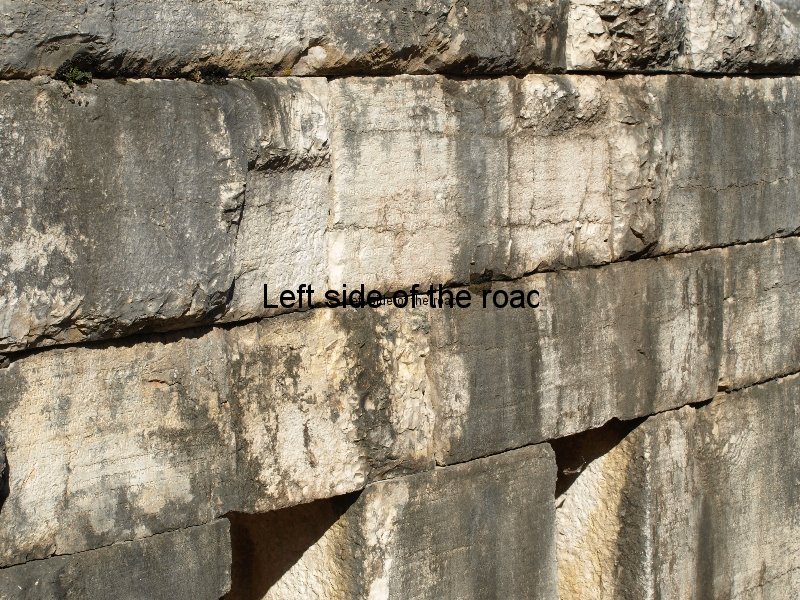

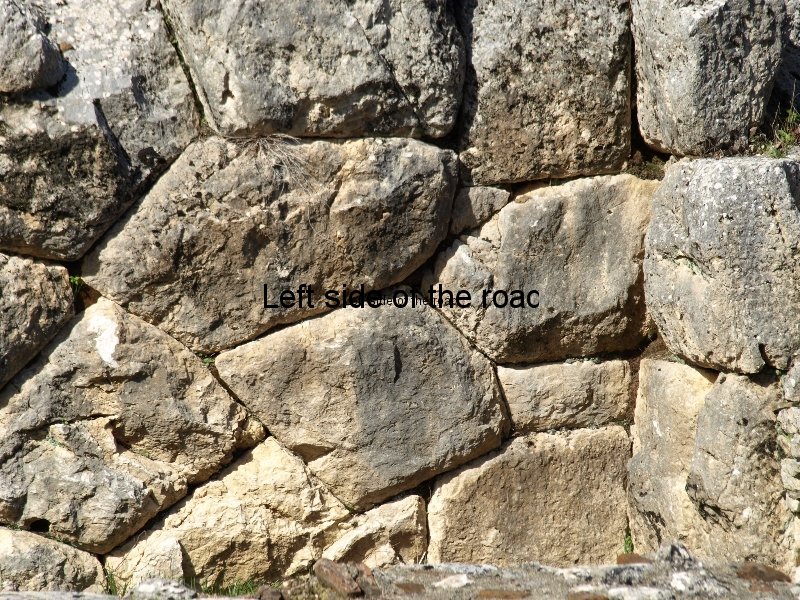

The city was walled and originally would have been much closer to the coast. That’s difficult to imagine nowadays as the beaches of Badalona are a long way from the museum. However, everything falls into place when you remember that to the south-west, just under halfway to Barcelona, is the River Besos. Its delta in the past was much more extensive and the years of taking water from further upstream for agriculture and its ‘taming’ close to human settlements has changed the ecology of the littoral.

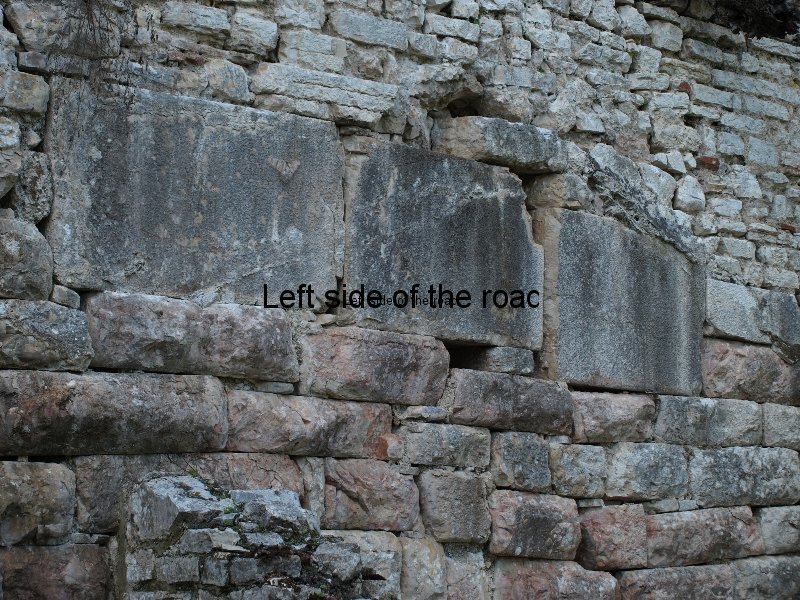

Excavation of the site were the museum now stands began in 1955 and soon after it was decided to build the museum on top of it to aid in its preservation. I’m not sure if I am a big fan of such preservation. Yes, it does prevent erosion and other damage caused by the weather but it makes for a strange experience when visiting the site. Recent modernisations and improvements to the exhibition space have meant that you see the ruins in very subdued light and creates a sensation quite unlike any other such archaeological site I’ve visited. The city that originally would have been bleached and burnt by the Mediterranean sun now exists in a permanent twilight, with all the concrete and metal surfaces of the modern building being painted black.

Nonetheless, what you get is a very good idea of what a Roman town would have been like, there being set conventions and structures that were common in settlements of the Republic and Empire that were repeated for the 500 years or so before internal conflict and foreign invasion saw the inevitable end of the most powerful empire up to that time. More recent empires can only dream of such a period of dominance – just remember the Nazi dream of a ‘Thousand Year Reich’ and the way that US dominance of the world is being threatened by the upsurge in the Chinese economy.

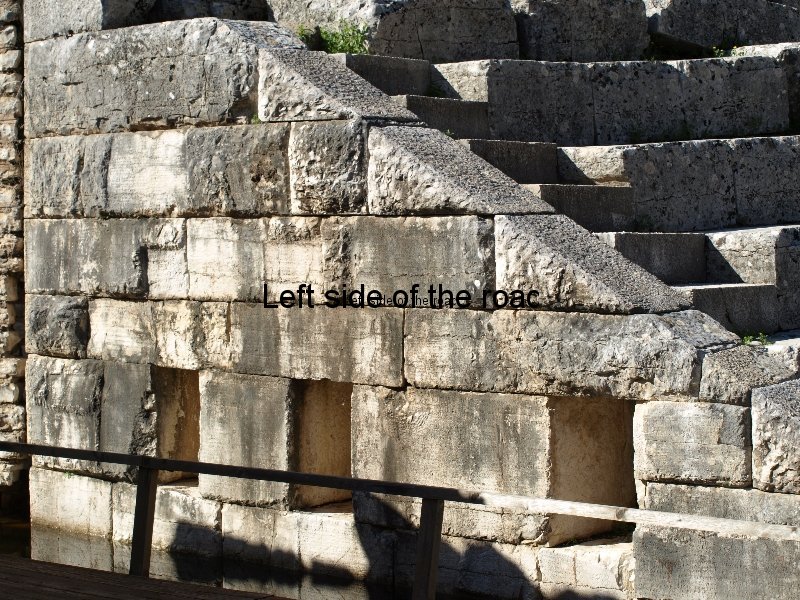

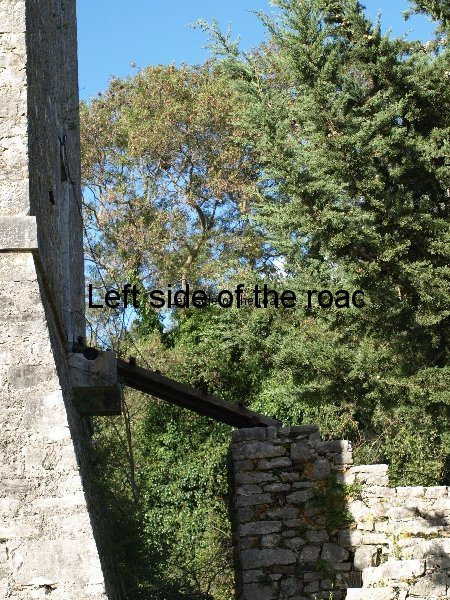

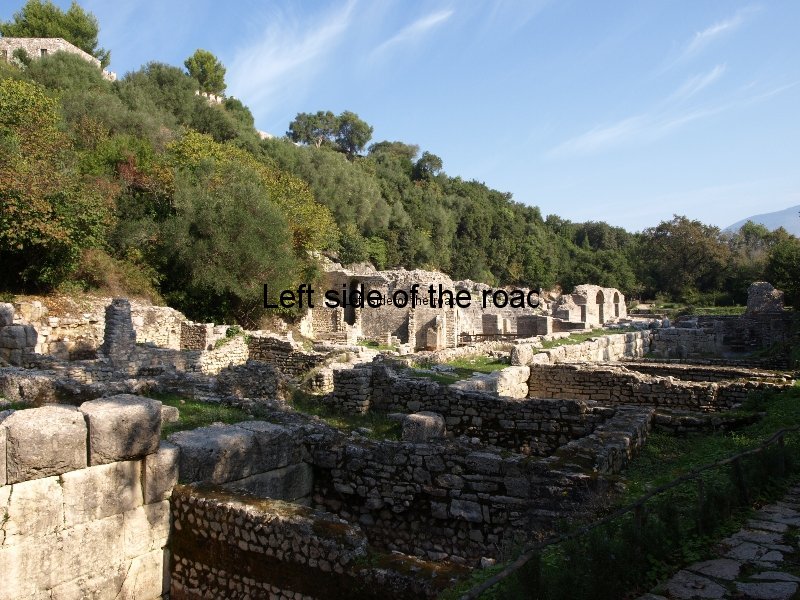

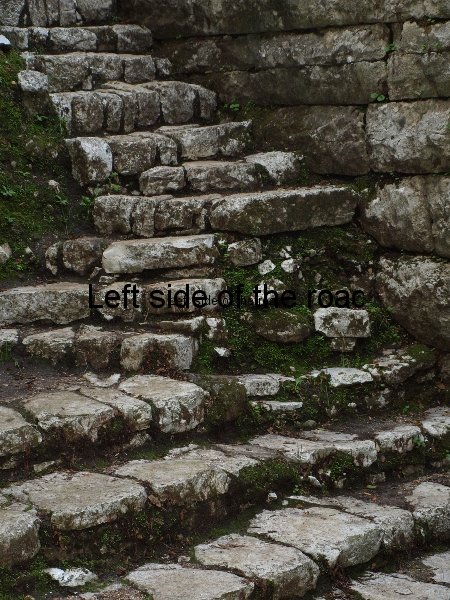

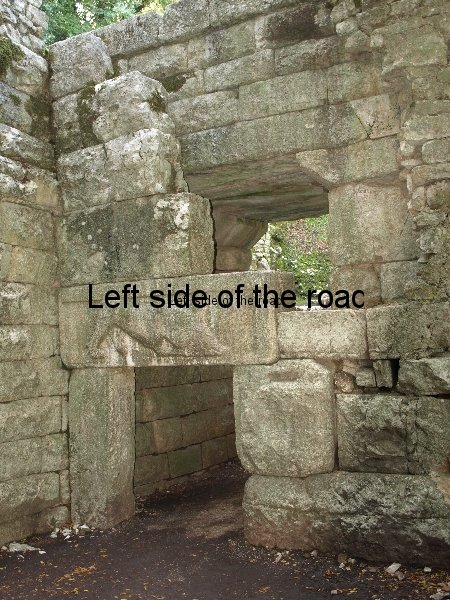

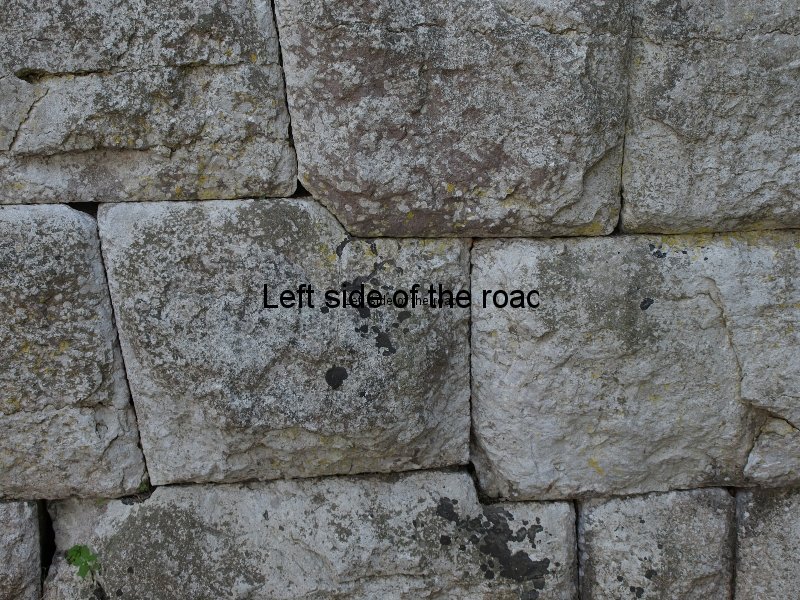

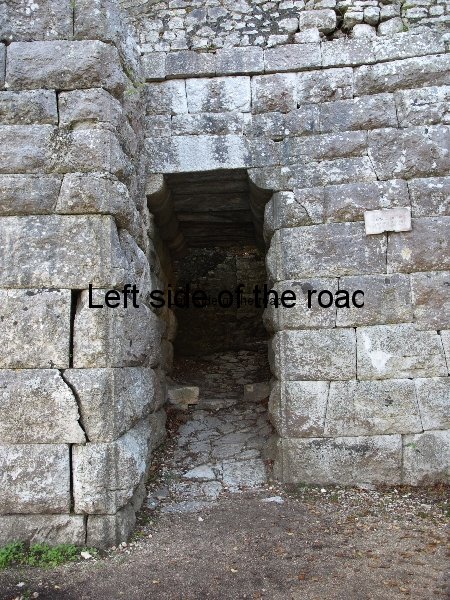

The area in the museum, which covers about 3,400 m², must have been the earliest to have been built as parts of the Cardo Maximus and Decumanus Maximus are both within the uncovered site. These roads were the two principal thoroughfares around which the rest of the city would be constructed.

The Cardo Maximus took an east-west orientation, often strictly adhering to the points of the compass, but in Baetulo the line of the coast was taken as the point of reference (as well as the compass) so here this main street runs from the coast to the mountains. The Decumanus Maximus was normally constructed along a north-south axis but in Baetulo is parallel to the coast. At the ends of these two main roads you would have found the gates into the walled town. Also it was traditional that the Forum would have been built at their intersection and that would place it, more or less’ in the top left hand corner of the site, just to the left of the exhibition area. When the town was first constructed the Forum would have been very much in the centre of the settlement but as the place grew in importance it expanded massively and reached about 10 hectares in size before its decay in the 6th century AD (CE in modern parlance).

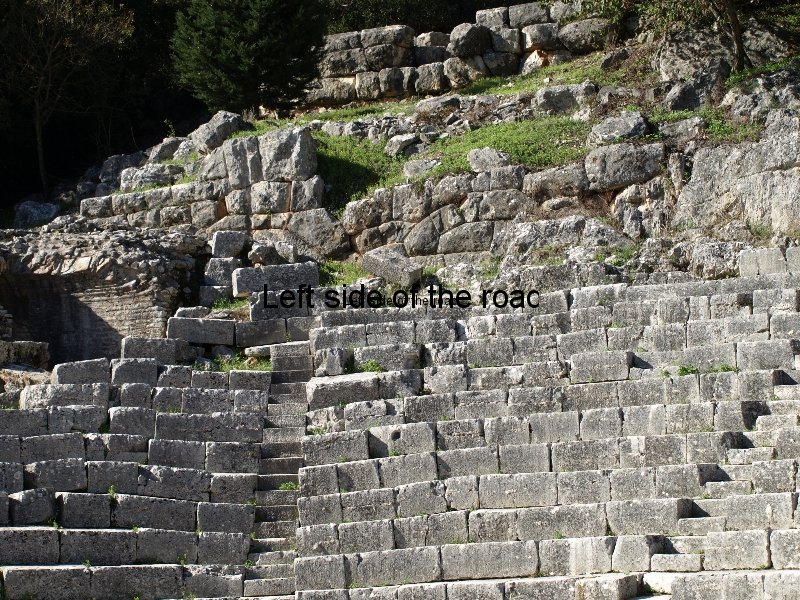

What of the buildings on show. One of the main areas, and one of the most important in any Roman town, is that of the bath house (thermae). These always followed a very regular pattern and anyone who has already visited a Roman town will be aware of the arrangement.

First there’s the atrium, which is the first room on entry where entrance fees were paid and people would meet up with their friends, business acquaintances or fellow plotters if something nefarious was on the cards.

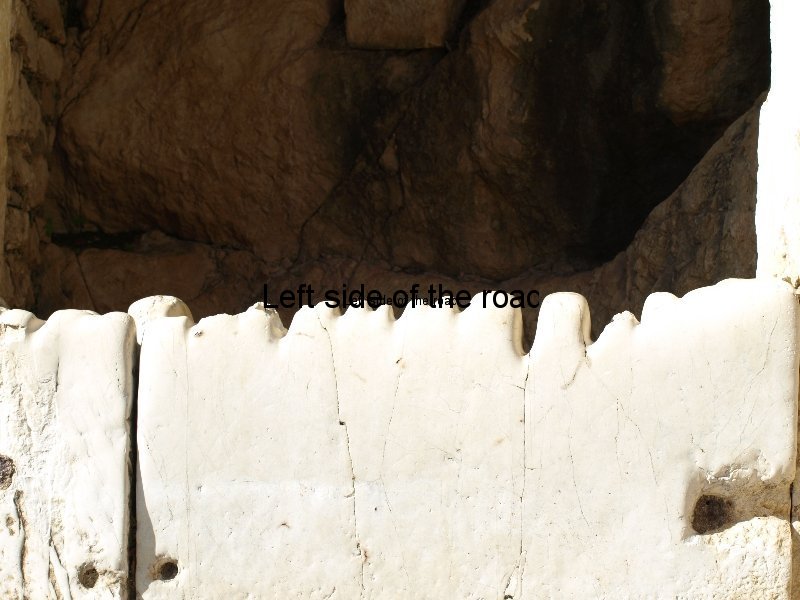

The baths proper began with the apodyterium (the changing room) and connected to that is the frigidarium (a cold plunge pool). Through a doorway next there’s the tepidarium (the warm room, so that customers would be able to adapt to the rising temperatures). This was a place to sit and talk and at Baetulo they have reconstructed a bench to give a better impression of the look of the room – many years in the past the original bench had been taken and all that was left was the depression in the floor. This is also the room with the only mosaic on show (there are more at another nearby site, the House of the Dolphins). Although much of the worked stone would have been looted once the Roman town fell into disuse the mosaics survive as stealing them would be like stealing a jigsaw puzzle where the box lid had been lost.

Next to that is the caldarium (the really hot room), what we would now call a sauna. This was closest to the fire which provided all the heat through under floor channels and vents. You look down on these rooms from the metal walkway that leads you around the site.

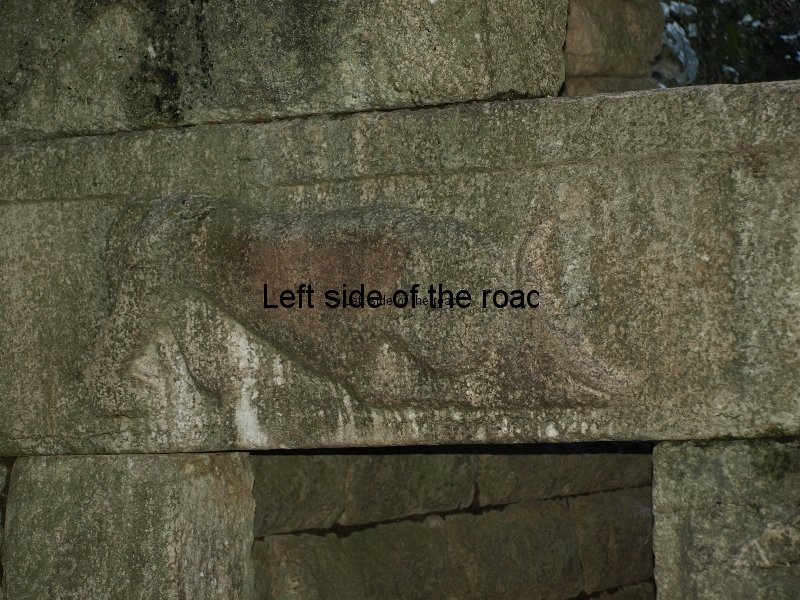

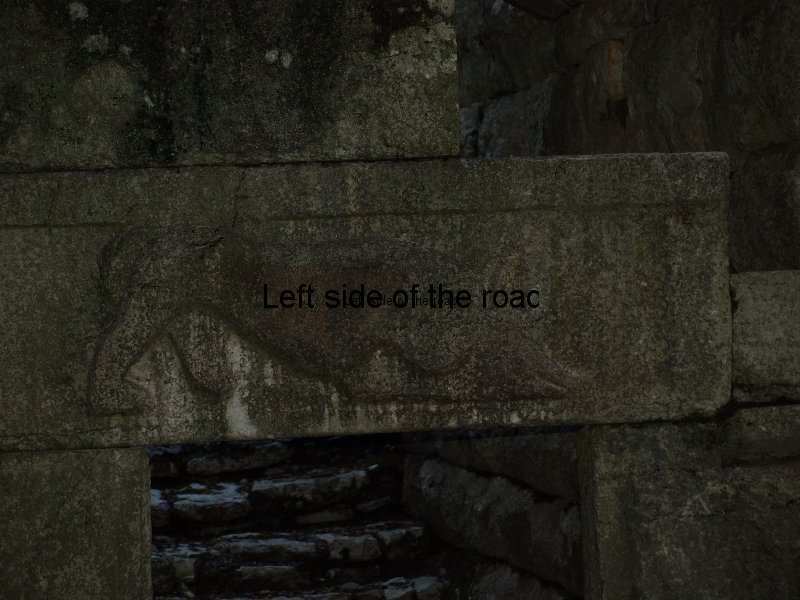

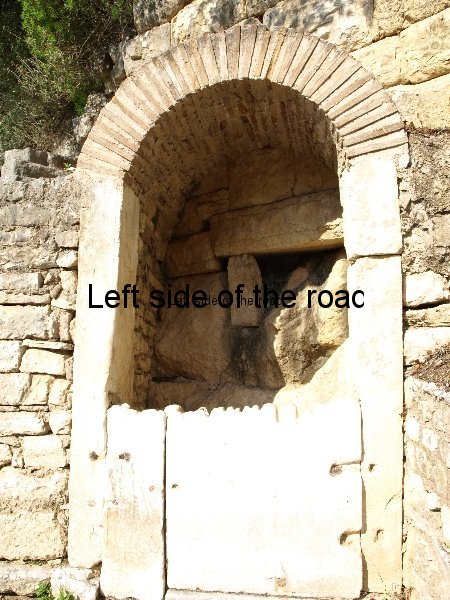

Traditionally along the two major roads virtually every building would have a commercial use at street level – any living accommodation here being on the first floor – all ready to get people’s money as they came through the city gates. These premises would be a mix of shops, taverns and brothels – although the information boards are quiet about the latter product of the free market. Here it’s worth mentioning that there’s a lot of information on these panels, by each building or place of interest, in three languages, Catalan, Spanish and English.

One of the good things about visiting these different sites is that either a new piece of information is pointed out to you or you see something that makes you think in a different way. Here looking down at a modest house, more like a one room bedsit, our guide pointed out that there were rarely any cooking facilities in the more modest homes and that all cooked meals would be taken in the local taverns, something which is still seen in certain parts of the world to this day. (I’ve noticed a similar situation in countries as far apart as Peru and Vietnam.) Also there’s one building that still has the remains of wall paintings and another that’s been identified as a workshop.

However, the aspect of the site that’s very obvious is the importance the Romans placed on their drainage and sewerage system (cloacas in both Catalan and Spanish). As what has been uncovered contains parts of the two principal streets it’s possible to see how the system goes from the smaller channels from each building, then into the smaller streets and finally from there to the main drains which go downhill towards the sea. I can’t imagine that anyone would want to swim in the Mediterranean just below Baetulo but the system meant that all the filth was kept away from where people lived, ate, shopped and worked. The remains of a water supply duct constructed in the time of Tiberius, in the 1st century AD, can be visited only a couple of hundred metres away from the museum.

It’s one of those questions which will never get a satisfactory answer. Once the Romans lost their power, in all parts of the known world where they had a presence, the marble, the worked stone, anything of removable value was looted but it seems that no one thought to ‘steal’ (or even borrow) the knowledge of underground heating, providing a clean water supply and getting rid of human waste. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that these issues were accepted as needing a solution in order to make it possible to actually live in the major industrial cities that were mushrooming with the advance of the industrial revolution. Up to that time most cities were literally cesspits of filth, stench and disease. We started to get it right in Britain for about a hundred years but now we’re going backwards as privatisation puts profit before anything else. The only benefit from that, together with fracking, is that soon people will be able to get their gas and water through the same pipe. (See the 2010 film Gasland.) To the best of my knowledge the water and drains in Roman times were a public enterprise.

The basement also houses an exhibition space with artefacts found within the area of the old Roman town as well as an audio-visual presentation that, through the use of Computer Graphics Imaging, attempts to give an idea of what the city would have looked in its heyday (together with graffiti on the walls).

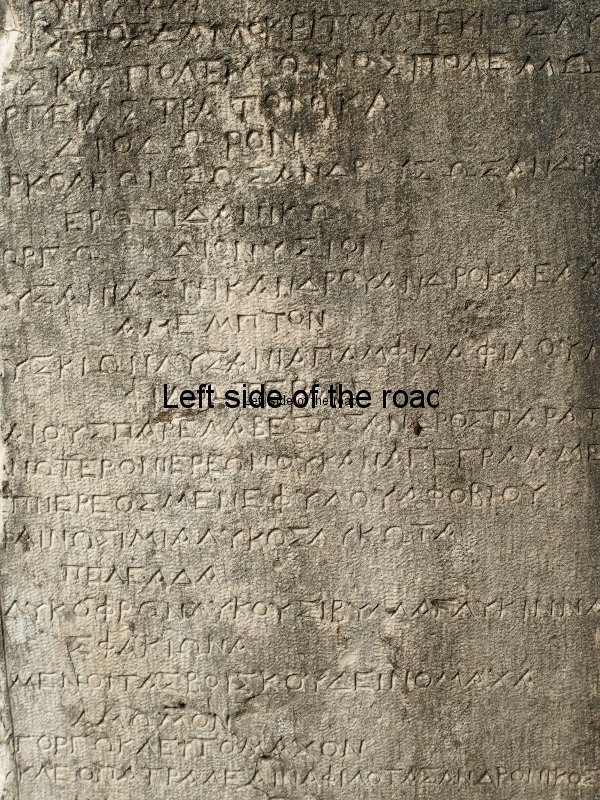

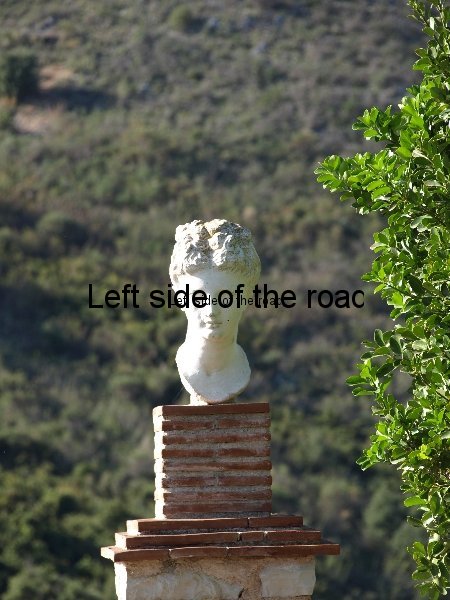

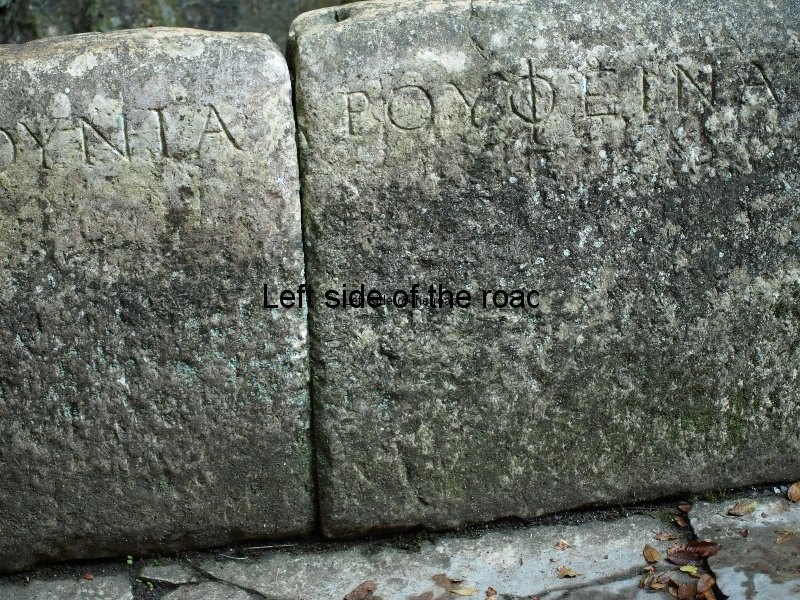

The collection, which is well presented, contains the ‘usual’ articles you find in such museums: amphora – for the storage and transport of, in the main, olive oil and wine; little pottery olive oil lamps for lighting – being so used to instant light at the flick of a switch we forget that in previous times light was at a premium and there must have been millions of these delicate and often beautifully decorated vessels made during the time of the Republic and Empire; sculptured heads on a spike – the bodies of the statues were made on a production line process and the individual heads were then added to order, this meant that when an Emperor was deposed they only had to change the head; pieces of glass and ceramics used in everyday life and which were discarded in huge quantities – so much of archaeological knowledge comes from people sorting through previous generation’s rubbish; funereal stelae, including three from the Iberian period; capitals and pieces of columns that had either been missed by looters or thought of no use; toys for children and pieces of wood, bone or stone that had been shaped and carved for use in games for both children and adults; and, as always, a small collection of erotica used as amulets and sometimes on a much bigger scale.

As is often the case each of these museums/exhibitions will have their unique finds and that’s the case with Badalona. One object is called The Badalona Venus. This is a beautifully carved and extremely anatomically accurate statue of a young woman. It would have stood about 18 inches high but unfortunately all that remains is the torso, the head, arms and the lower legs having suffered the ravages of time. These statues are often given great importance as symbols of love, fertility, desire, wealth and all the rest. It might have been all of those or none but it is still a very attractive statue and perhaps more so due to its small size, something that might have been lost if it was bigger.

I don’t know why I hadn’t thought of it before but on looking on this Venus I started to wonder why the skill of artistic perspective was lost at the same time as the knowledge of sewer construction – and other technological advances of the time. In Romanesque Art (from about 1,000 to the rise of the Gothic and then the Renaissance 3 or 4 hundred years later) the human figure is represented in a comic, grotesque, primitive, naïve way depending upon the location. Not that it doesn’t have charm, and in Barcelona it’s possible to see one of the best collections of such art in Europe in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, but it lacks perspective. That skill only started to re-emerge during the Renaissance but for almost a thousand years it was lost.

And that’s disturbing. If we neither learn from our mistakes or successes then we are well and truly snookered. Knowledge, it seems, is not linear in that we can gradually, perhaps sometimes in leaps and bounds, learn more and more. We have to forget, at times for many, many years before we can return to the road towards a higher understanding.

Before I depress myself too much I’ll return to those artefacts in the Badalona Museu that are relatively unique. And the two I’m going to highlight are both made of metal.

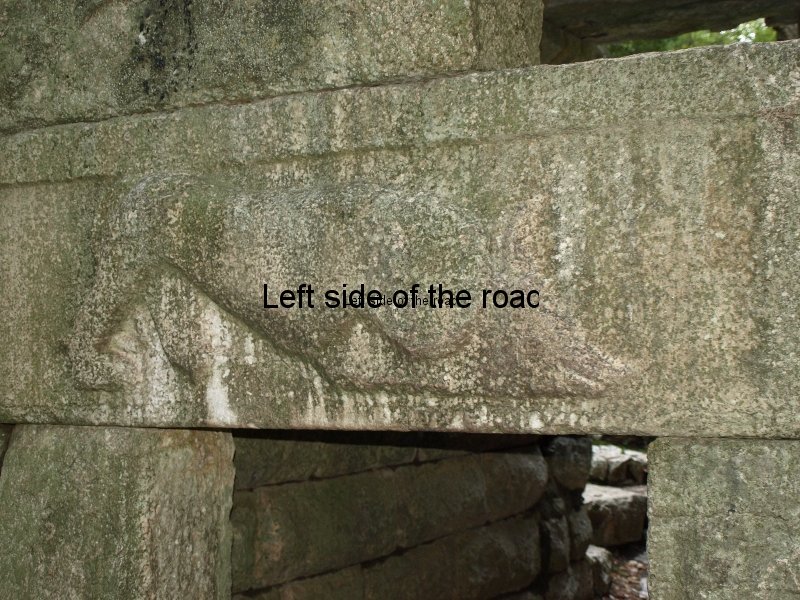

I’ve already mentioned that the Cardo and Decumanus Maximus roads would lead to the city gates and in the excavations in the area two bronze sockets were found which would have held the wooden jambs for those substantial gates.

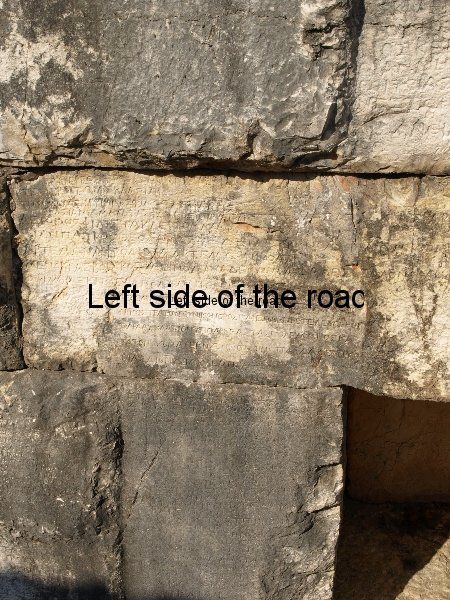

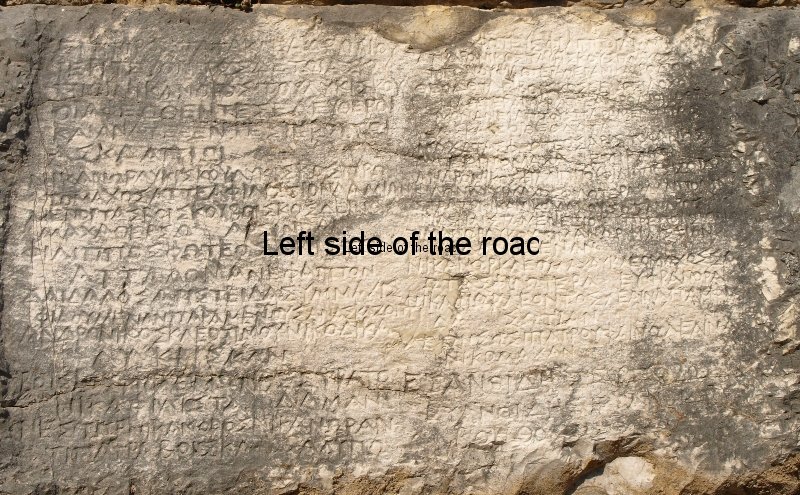

The other metal object is from the end of the 1st century AD and is known as the Tabula Hospitalis (a contract and binding agreement dating from Greek times establishing the norms of hospitality towards guests and visitors), a bronze plaque which records the agreement between the population of the town and the patrician Quint Licini Silvà Granià (part of the grounds of what are considered to have been attached to his house are another area that had been excavated and which can be visited).

So in a relatively small space a lot to see.

A short video to give you a taste of the site can be seen by clicking here

After a tour that lasted about an hour and a half it was our guide, the Directora of the Archive, who suggested we could do a lot worse than try Can Joan for a €10 lunchtime menu (that’s, of course, if you visit in the morning).

Thanks to Montse and Esther of the Badalona Museum for permission to use the photos of Antonio Guillén.

Location:

Museu de Badalona

Plaça Assemblea de Catalunya, 1

08911 Badalona

Tel: +34 933 841 750

Opening Times:

Tuesday – Saturday from 10.00 – 14.00, 17.00 – 20.00

Sunday and Holidays from 10.00 – 14.00

Closed: Mondays, 1st and 6th January; 1st May; 24th June; 15th August; 11th, 25th and 26th September

Cost:

€6.48 – which includes the House of the Dolphins and Quint Licini Garden

Pensioners: €2.70

Website: Museu de Badalona

How to get there:

Go the very end of L2 (the purple one) on the Metro at Badalona Pompeu Fabra. From the main exit go up hill to the next set of traffic lights and cross Avinguda de Martí Pujol and then go along Via Augusta for a couple of hundred metres. The Museum is on the corner of Via Agusta and Carrer de les Termes Romanes.

Instead of rushing out of the Metro, which is the norm in all parts of the world, stay a while and take a look at the pictures in the upper vestibule of the recently modernised station. These are images of the Devils (and the year of their construction) which have been burnt on the night of the 10th May as part of the the May Festival. This act records the attempt of The Devil to seduce who was to become the patron saint of Badalona, Sant Anastasi.