The Great ‘Marxist-Leninist’ Theoreticians

The Writings of Chairman Mao Tse-tung

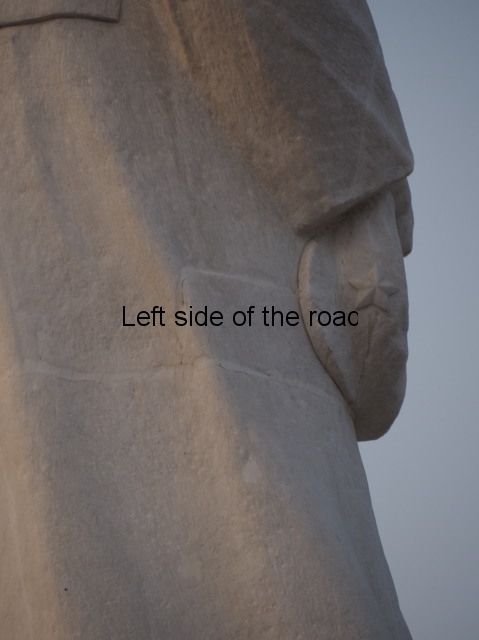

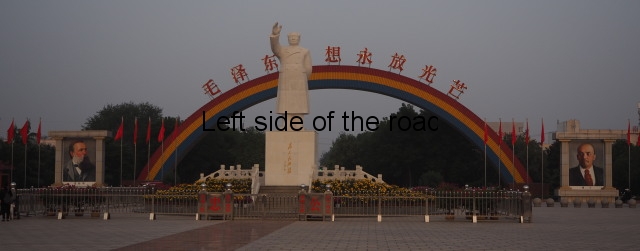

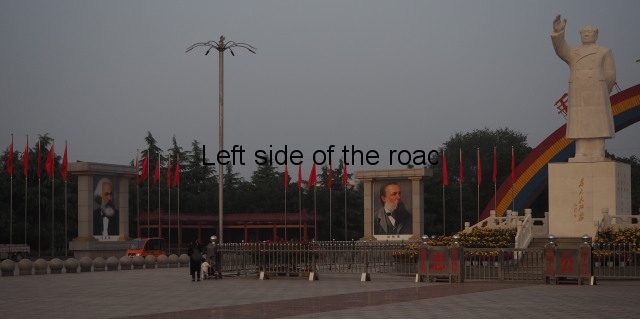

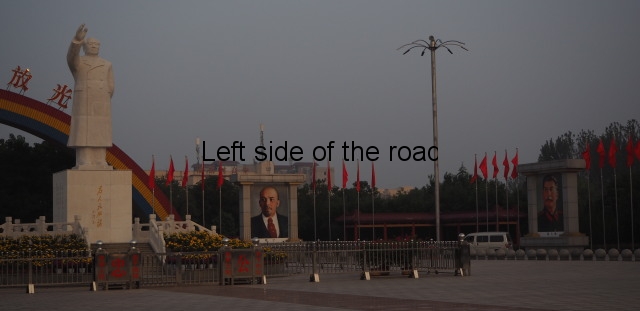

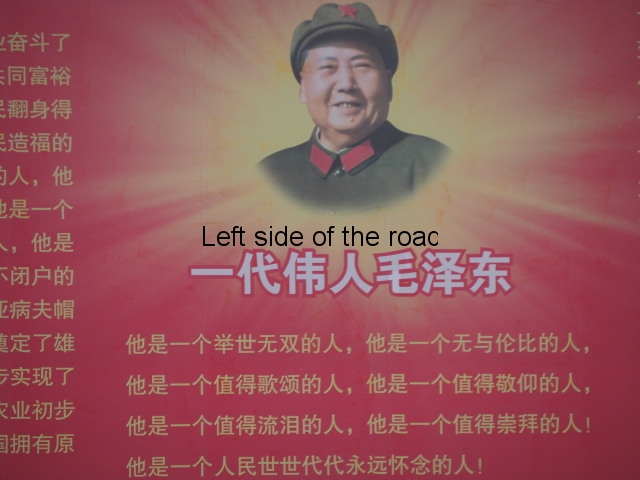

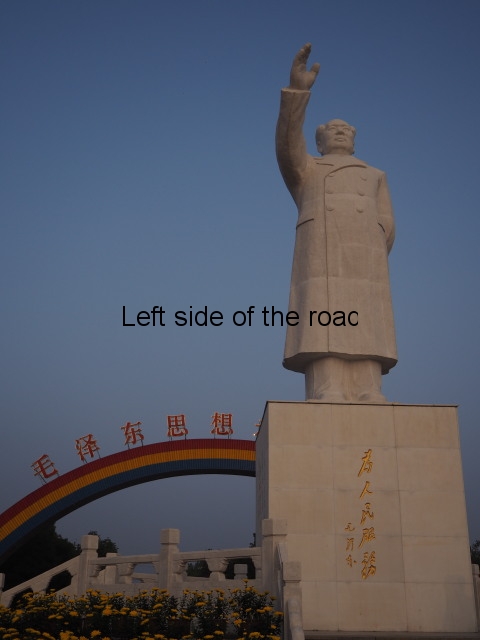

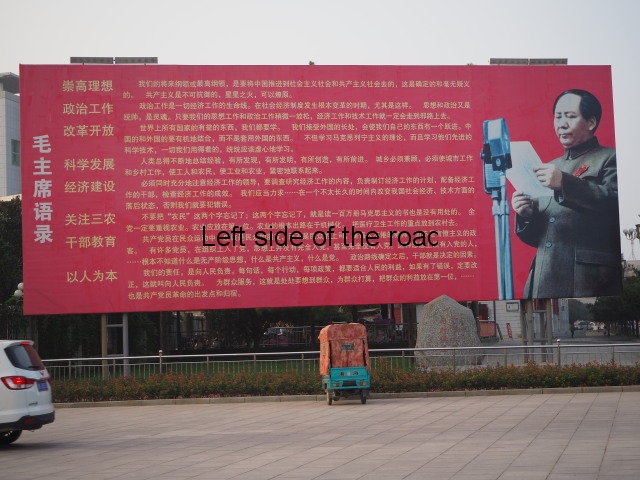

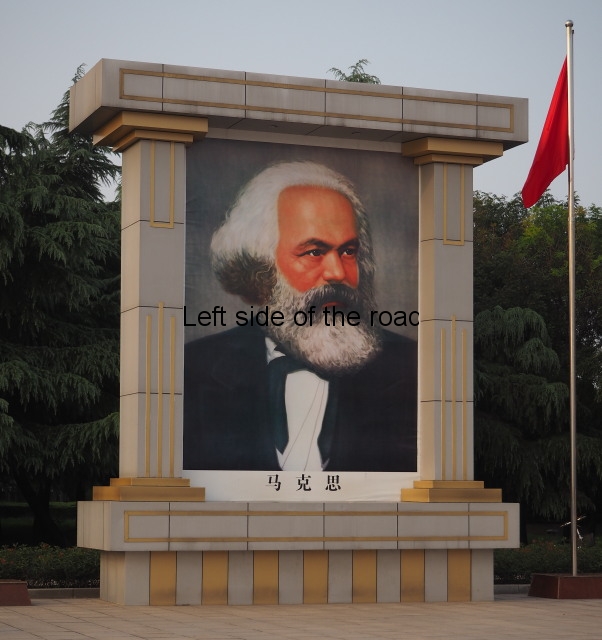

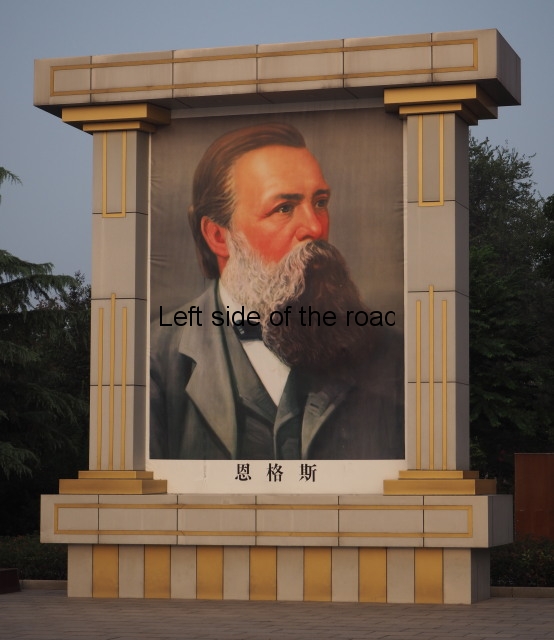

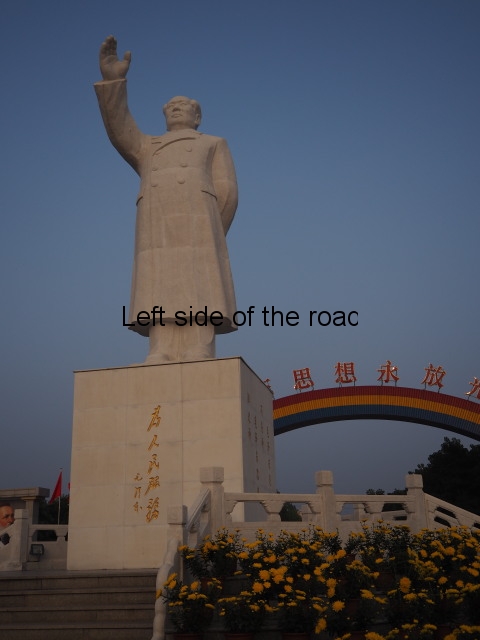

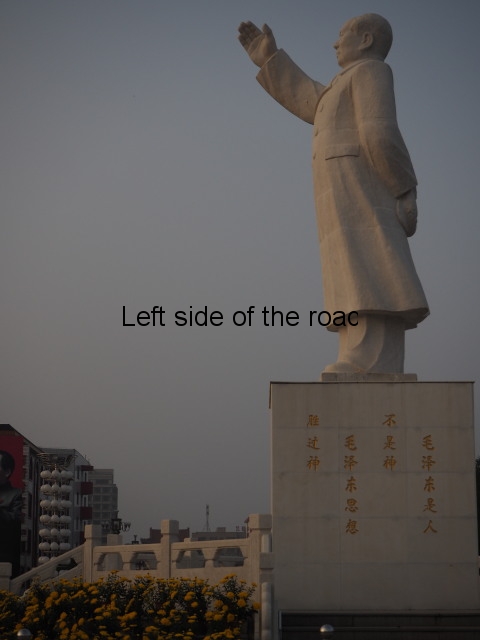

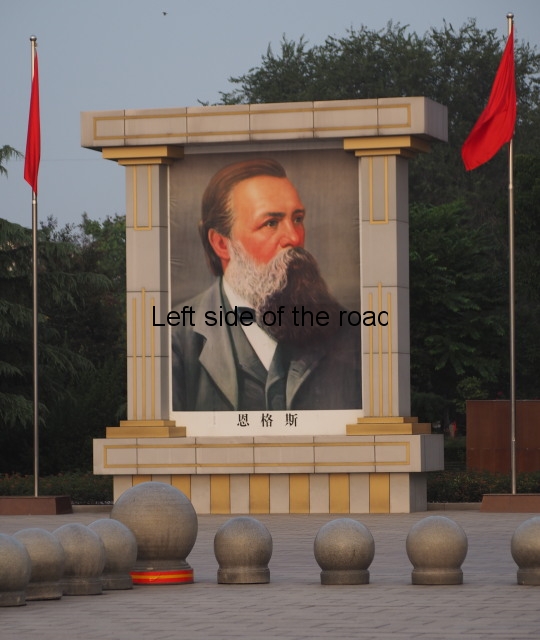

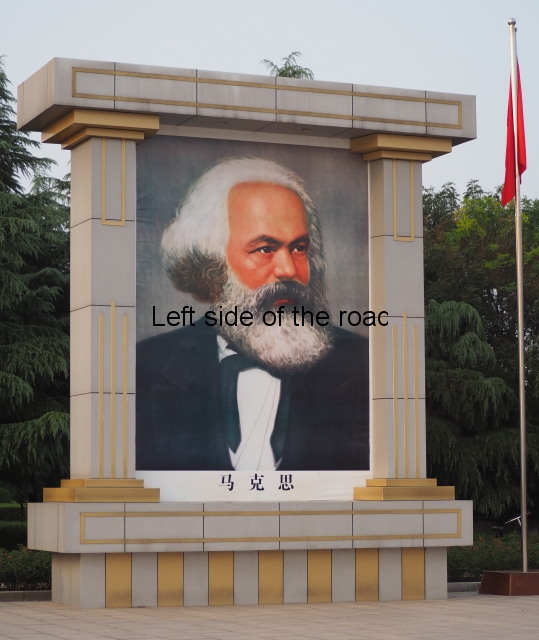

Chairman Mao Tse-tung was one of the small group of towering giants produced as a result of the struggles of the workers and peasants throughout the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. (The others were Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, Joseph Stalin and Enver Hoxha.)

Selected Works – published during the period of Socialism

The decision to published a comprehensive collected of the written works of Chairman Mao Tse-tung was taken in the early days of the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution, appearing in many world languages in a very short period of time. However, the 4 volumes produced during that period only went up to 16th September 1949, a couple of weeks before the Declaration of the People’s Republic. For this reason the ‘official’ Selected Works only includes these 4 volumes.

Selected Works, Volume 1, FLP, Peking, 1967, 362 pages.

The First and Second Revolutionary Civil War Period – March 1926 – August 1937.

Includes many important works such as:

Analysis of classes in Chinese Society

A Single Spark can Start a Prairie Fire

On Practice

On Contradiction

Selected Works, Volume 2, FLP, Peking, 1967, 484 pages.

The Period of the War of Resistance Against Japan (I) – July 23rd 1937 – May 8th 1941

Includes many important works such as:

Combat Liberalism

Problems of Strategy in Guerrilla War Against Japan

On Protracted War

On New Democracy

Selected Works, Volume 3, FLP, Peking, 1967, 304 pages.

The Period of the War of Resistance Against Japan (II) – March 1941 – August 9th 1945

Includes many important works such as:

Reform Our Study

Talks at Yenan Forum on Literature and Art

On Coalition Government

The Foolish Man who Removed the Mountains

Selected Works, Volume 4, FLP, Peking, 1969, 472 pages.

The Third Revolutionary Civil War Period – August 13th 1845 – September 16th 1949

Includes many important works such as:

Talk with the American Correspondent Anna Louise Strong

Correct the ‘Left’ Errors in Land Reform Propaganda

Carry the Revolution Through to the End

Index to Selected Works (and Selected Military Writings)

An academically produced index of the four ‘official’ volumes of the Selected Works of Chairman Mao Tse-tung which might be found useful.

Index to Selected Works of Chairman Mao, Union Research Institute, Hong Kong, 1968, 190 pages.

Selected Works – produced in the early stages of the counter-revolution

Only one further volume of the Selected Works of Chairman Mao Tse-tung was produced by the state-run Foreign Languages Press in Peking. It was produced whilst the coup for the leadership of the Communist Party of China was still in progress. Produced within a year of the Chairman’s death was probably too short a time for serious political ‘revision’ to have occurred but this has to be considered when referring to contentious issues that might appear in this volume. Although there was an intention to continue the production of the Selected Works nothing else appeared after Volume 5. (The ‘Publication Note’ on pages 5-6 gives an idea of the situation of flux at the time of publication.)

Selected Works, Volume 5, FLP, Peking, 1977, 534 pages.

The period of the Socialist revolution and Socialist Construction (I) – September 21st 1949 – November 18th 1957

Includes interesting, and some important, works such as:

Liu Shao-chi and Yang Shang-kun Criticized for breach of Discipline in Issuing Documents in the Name of the Central Committee Without Authorization

Combat Bourgeois Ideas in the Party

On the Correct handling of Contradictions Among the People

Concordance of proper nouns in the five-volume English language Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung, compiled by Harry M Lindquist and Roger D Mayer, Centre for East Asian Studies, University of Kansas, 1968, 72 pages.

Selected Works – collected together outside of China

Once it became clear that the Chinese Revisionists would not be publishing more of Chairman Mao’s Selected Works (or that they couldn’t be trusted if they did) various groupings around the world made attempts to glean through the mass of paperwork and try to determine what might have been produced by the Chairman. This was not as difficult as it might first be thought. Chairman Mao had a very distinctive style and anyone steeped in his work would be able to make a more than intelligent guess whether a work was by him or not. This was especially the case during the early days of the Cultural Revolution when many editorials or unsigned articles were almost certainly from the pen of the great Socialist leader.

The first of those (under the name Volume VI) goes away from the style of the first Five volumes in that it attempts to pick up articles and writings that might have been omitted from those earlier volumes.

Selected Works, Volume VI, Kranti Publications, Secunderabad, India, 1990, 343 pages.

From April 1917 – April 1946

Includes titles such as:

Oppose Book Worship

The League of Nations is a League of Robbers

To be Attacked by the Enemy is not a bad Thing but a Good Thing

A revised, and more complete, edition was published in 2020.

Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung: Volume VI (2020), Kranti Publications, Secunderabad, India, 2020, 448 pages.

Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung: Volume VII (2020), Kranti Publications, Secunderabad, India, 2020, 464 pages.

Letters, telegrams and directives from September 23rd 1949 to November 17th 1957.

Volume VIII is a work in progress but we have access to to downloadable version, of what has already been produced, so that is included here.

Selected Works, Volume VIII – partial, Maoist Documentation Project, 2004, 353 pages.

From January 1958-1961

Includes titles such as:

Red and Expert

Communes are Better

Critique of Stalin’s ‘Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR’

Volume IX, produced in India in 1994, returns to the format first used in China in 1967. What’s important about this edition is that this is the first attempt to cover some of the crucial years of the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) in any depth.

Selected Works, Volume IX, Sramika Varga Prachuranulu, Hyderabad, 1994, 474 pages.

From May 1963 – September 12th 1971

Includes articles such as:

Where do the Correct ideas Come From?

The Soviet Leading Clique is a Mere Dust Heap

Talk at a Meeting of the Central Cultural Revolution Group

Speech to the Albanian Military Delegation

The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949-1976, Volume 1, September 1949-December 1955, edited by Michael Y. M. Kau and John K Leung, ME Sharpe, New York, 1986, 771 pages.

The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949-1976, Volume 2, Janauary 1956-December 1957, edited by Michael Y. M. Kau and John K Leung, ME Sharpe, New York, 1992, 863 pages.

A critique of soviet economics by Mao Tse-tung, with an introduction by James Peck, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1977, 157 pages.

Mao’s critique of two Soviet books; Political Economy – A Textbook and Joseph Stalin’s Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR.

Mao Zedong On Diplomacy, FLP, Beijing, 1998, 516 pages.

This is a strange one, taking into account where (Beijing) and when (a 1998 translation of the Chinese edition of 1994) it was published. This doesn’t mean that the translations are not accurate or complete (although they might be) but in reading them we must have, at the back of our mind, why were they produced at that particular time.

Mao Zedong on Dialectical Materialism, Nick Knight, ME Sharpe, New York, 1990, 295 pages.

A detailed look at some of the essays that Chairman Mao produced whilst in Yenan in 1937. This was to culminate in the seminal works of On Contradiction and On Practice.

For Mao – Essays In Historical Materialism, Philip Corrigan, Harvie Ramsey and Derek Sayer, Humanities press, New Jersey, 1979, 207 pages.

Chairman Mao talks to the people – Talks and Letters – 1956-1971, edited by Stuart Schram, Pantheon Books, New York, 1974, 352 pages.

A collection of documents which were published in China as part of the struggle against counter-revolutionaries within the Party during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

The Secret Speeches of Chairman Mao – From the Hundred Flowers to the Great Leap Forward, edited by Roderick MacFarquhar, Timothy Cheek and Eugene Wu, Harvard Contemporary China Series No 6, 1989, 561 pages.

Speeches from 1957 and 1958.

Mao Papers – Anthology and Bibliography, edited by Jerome Ch’en, Oxford University Press, London, 1970, 221 pages.

The Thought of Mao Tse-tung, Anna Louise Strong, Communist Party of Great Britain, ND, 36 pages.

The following volumes contain various material produced by Chairman Mao in the years before the declaration of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949. They have been collected from numerous sources and their validity and accuracy cannot be verified. As with all collections of Mao’s writing published after his death, whether in China or outside, these have to be treated with care. The very title of the books (Mao’s Road to Power) should already start the alarm bells ringing. There are too many entities with an agenda to distort what he had written but are included here with the aim of making as much material as possible available to those with an interest in the ideas of one of the most significant thinkers of the 20th century.

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 1, Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, Volume 1 – The pre-Marxist period, 1912-1920. edited by Stuart Schram, ME Sharpe, New York, 1992, 639 pages.

Early writings of the young Mao Tse-tung as he was developing his own ideas before adopting Marxism as the basis of his ideology.

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 2, Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, Volume 2 – National Revolution and Social Revolution, December 1920 – June 1927, edited by Stuart Schram, ME Sharpe, New York, 1994, 543 pages.

The period in the 1920s when Mao was involved with both the Kuomintang and the young Chinese Communist Party, having an impact upon both.

The following volume (No 3) is in two parts due to file size limitations.

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 3 – Part 1

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 3 – Part 2

Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, Volume 3 – From the Jinggangshan to the establishment of the Jiangxi Soviets July 1927 – December 1930, edited by Stuart Schram, ME Sharpe, New York, 1995, 771 pages.

Writings by Mao about the development of the Chinese Communist Party.

The start of Mao’s interest, and study, of military strategy and tactics.

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 4, Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, Volume 4 – The Rise and Fall of the Chinese Soviet Republic 1931-1934, edited by Stuart Schram, ME Sharpe, New York, 1997, 1004 pages.

The period of the Chinese Soviet republic in Jianxi and inner-Party struggles within the Communist Party of China

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 5, Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, Volume 5 – Toward the Second United Front, January 1935 – July 1937, edited by Stuart Schram, ME Sharpe, New York, 1999, 737 pages.

Covering the period of The Long March.

The following two volumes (Nos. 6 and 7) are also in two parts due to file size limitations.

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 6 – Part 1

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 6 – Part 2

Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, Volume 6 – The New Stage, August 1937 – 1938, edited by Stuart Schram, ME Sharpe, New York, 2004, 867 pages.

The time of the United Front with the Kuomintang against Japanese aggression.

The period in which Mao outlined his interpretation of Dialectical Materialism in works such as On Contradiction and On Practice.

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 7 – Part 1

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 7 – Part 2

Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, Volume 7 – New Democracy, 1939-1941, edited by Stuart Schram, ME Sharpe, New York, 2004, 897 pages.

The period of the development of guerrilla warfare and the establishment of base areas behind Japanese lines.

The tactic of flexible united fronts with the Kuomintang and various other groupings.

Mao’s Road to Power – Volume 8

Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, Volume 8 – From Rectification to Coalition Government, 1942-July 1945, edited by Stuart Schram, Routledge, New York, 2015, 1436 pages.

When Chairman Mao stressed the necessity of aligning Marxist-Leninist theory with the Chinese reality, the Rectification Campaign.

The Thought of Mao Tse-Tung, Stuart Schram, Cambridge University Press, London, 1989, 242 pages.

Writings and Speeches, unofficial English translation of the sections of The Complete Works of Mao Zedong written during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Translation, footnotes, and introduction provided by Nick G. of the Communist Part of Australia (Marxist-Leninist). As noted in his introduction, these translations relied partially on machine translators.

1966: Writings and Speeches, 220 pages.

1967: Writings and Speeches, 343 pages.

1968: Writings and Speeches, 182 pages.

1969: Writings and Speeches, 89 pages.

1970: Writings and Speeches, 113 pages.

1971: Writings and Speeches, 110 pages.

1972: Writings and Speeches, 69 pages.

A selection of letters, compiled by the Party Literature Research Centre under the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the Central Archives, Cultural Relics Publishing House, 1983, 93 pages.

Miscellany of Mao Tse-tung Thought (1949-1968), two volumes, U.S. Department of Commerce, Joint Publications Research Service, Arlington, February 1974. These are the U.S. government translations of Red Guard volumes from the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Source: Selected items from two Chinese-language volumes, Mao Tse-tung Ssu-hsiang Wan-sui (Long Live Mao Tse-tung Thought) totalling 996 pp, published in 1967 and 1969, with no other publication information or attribution. Those items in these two volumes which are already generally available in English-language translation in various publications were not selected for translation and publication in this report. The items in this report are arranged in chronological order irrespective of the Chinese language volume in which they were published.

Part 1, 246 pages. (Has some underlining and marginal notes.)

Part 2, 270 pages.

A Collection of ‘In Camera Statements of Mao Tse-tung’, 1943-1966 (but most from the late 1950s), unofficial translations which appeared in the Western academic journal Chinese Law and Government, Volume 1, 34, Winter 1968-69, 112 pages.

Poetry

Mao Tse-tung Poems, FLP, Peking, 1976, 53 pages.

Many people may be surprised to learn that Chairman Mao was also an accomplished poet. Although one of the world’s most revolutionary thinkers his poetry very much follows the traditional style developed over the centuries.

Selected Readings

In the late 1960s/early 70s, as well as producing the Four Volumes of the Selected Works, the Foreign Languages Press also produced a volume of Selected Readings. This single volume contained many of the most important, and most studied, of Chairman Mao’s writings during the period of the Cultural Revolution – not just in China but in many countries of the world.

Selected Readings, FLP, Peking, 1971, 504 pages.

Mao Tse-Tung on Revolution and War, edited and with notes by M Rejai, Doubleday, New York, 1970, 452 pages.

A selection of articles prompted by the events of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Writings on Military Affairs

It is sometimes forgotten that as well as being the principal theoretical leader of the Chinese Revolution Chairman Mao was also a very able military commander. During his lifetime various collections of writings devoted to military affair were published. Although useful in a military sense to this day it is important top remember Chairman Mao’s dictum of always ‘putting politics in command’ – without that military success will always be transitory.

Selected Military Writings, FLP, Peking, 1963, 408 pages.

Contains articles such as:

Why is it Red Political Power can Exist in China?

On Correcting Mistaken Ideas in the Party

Problems of War and Strategy

Manifesto of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army

On Protracted War, FLP, Peking, 1967, 116 pages.

Not just a treatise on warfare but one of Chairman Mao’s most important contributions to Marxist-Leninist theory.

Six Essays on Military Affairs, FLP, Peking, 1972, 393 pages.

Six of the most important and relevant essays that Chairman Mao wrote related to the successful outcome of a military campaign.

On Guerrilla Warfare, US marine Corps, Washington, 1989, 128 pages.

A pamphlet with the basic principles of Guerrilla Warfare that was widely disseminated throughout ‘Free’ China after it was first published in 1937. Produced by the US military, thereby proving the importance of ‘knowing your enemy’. Surprisingly not published in the Selected Works.

Mao Zedong’s Art Of War, Liu Jikun, Hai Feng, Hong Kong, 1993, 277 pages.

A look at Chairman Mao’s military strategy as it was put into practice in the National Liberation War against the Japanese invaders and then the Civil War against the reactionary Kuomintang forces under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek.

Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung – The ‘Little Red Book’

Produced in millions, in dozens of languages, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, here we have short quotations that distil the essence of Mao Tse-tung Thought.

Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, FLP, Peking, 1966, 312 pages.

Literature and Art

From the very early days of the struggle to free his country from foreign domination Chairman Mao was aware of the importance of literature and art in any National Liberation struggle as it enabled the oppressed people to establish their own, independent identity. This was developed as the successful struggle of the Chinese People against the Japanese invaders developed into a Civil War for the establishment of a Socialist state. The importance of literature and art probably reached its apogee in China during the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution when the likes of Peking Opera was adapted to represent the struggles and desires of the working people. That theoretical basis came from Mao’s writings during the Anti-Japanese war of Resistance.

Mao Tse-Tung on Art and Literature, FLP, Peking, 1960, 145 pages. (Contains a lot of underlining.) An early compilation, with slightly different contents from the 1967 version (below).

On Literature And Art, FLP, Peking, 1967, 162 pages.

Includes:

Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art – May 1942

Reform Our Study

Oppose Stereotyped Party Writing

The Problem of Culture, Education and the Intellectuals

Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art, FLP, Peking, 1967, 42 pages.

Two presentations given at the conference in May 1942.

Five documents on Literature and Art, FLP, Peking, 1967, 12 pages.

Five very short articles addressing the issue of the importance of literature and art in the building of Socialism

Mao Zedong’s Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literaure and Art, a translation of the 1943 text with commentary, Bonnie S McDougall, Centre for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1980, 112 pages.

A new translation of Chairman Mao’s ‘Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art’ together with a commentary on the elements of literary theory that it contains.

On Philosophy

Separating Chairman Mao’s writings into different ‘categories’ is always going to be problematic as all aspects of the struggle are inter-related. This pamphlet, of four essays, was one of those most studied during the period of the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution.

Four Essays on Philosophy, FLP, Peking, 1966, 136 pages.

Contains:

On Practice

On Contradiction

On the correct handing of contradictions among the people

Where do the correct ideas come from?

The Wisdom of Mao Tse-tung, Philosophical Library, New York, 1968, 114 pages. (Quite a lot of underlining.)

Contains the three important articles; On Practice, On Contradiction and On New Democracy.

Five Essays on Philosophy, Foreign Languages Press, Utrecht, 2018, 189 pages.

On Contradiction Study Companion, Redspark Collective, Foreign Languages Press, Paris, 2019.

On Practice and On Contradiction, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2022, 101 pages.

Individual Pamphlets

Before the publication of the Selected Works and Selected Readings (downloadable above) many individual pamphlets were produced of the writings of Chairman Mao in the early 1960s, in advance of the Cultural Revolution. Some of those are reproduced below. More will be added as and when they become available.

China and the Second Imperialist World War, International Publishers, New York, 1939, 50 pages.

Addresses and interviews by Chairman Mao between May and October 1939.

China’s New Democracy, Progress Books, Toronto, 1944, 72 pages.

An article written by Chairman Mao in 1940 before the war in Europe expanded to include the Soviet Union and before its extension as a World War.

People’s Democratic Dictatorship, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1950, 40 pages.

Speeches made by Chairman Mao in 1949, just before the declaration of the People’s Republic of China.

On the tactics of fighting Japanese Imperialism, FLP, Peking, 1960, 41 pages.

Comrade Mao Tse-tung here explains, in great detail, the possibility and the importance of re-establishing a united front with the national bourgeoisie on the condition of resisting the Japanese.

On Strengthening the Party Committee System, FLP, Peking, 1961, 9 pages.

NO revolution of workers and peasants has achieved a modicum of success, with a chance of lasting more than the 61 days (which includes a week of slaughter of the Communards) of the Paris Commune in France (1871), WITHOUT an organised M-L Party. Get it wrong and the revolution will fail, thousands of workers will die and the revolution will be put back more than a generation.

Our study and the current situation, Appendix: Resolution on certain questions in the history of our Party, FLP, Peking, 1962, 90 pages.

This was a speech made by Comrade Mao Tse-tung at a meeting of senior cadres in Yenan on April 12th 1944 on the subject of the discussions about the history of the ‘Left’ elements within the Party between 1931 and 1934.

Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan, FLP, Peking, 1965, 52 pages.

This article was written in March 1927 as a reply to the carping criticisms both inside and outside the Party then being levelled at the peasants’ revolutionary struggle. Comrade Mao Tse-tung spent thirty-two days in Hunan Province making an investigation and wrote this report in order to answer these criticisms.

Notes On Mao Tse-tung’s ‘Report on an investigation of the peasant movement in Hunan’, Chen Po-ta, FLP, Peking, 1966, 56 pages.

Notes on Mao Tse-tung’s ‘Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan’, the Editorial Board of Jiefangjun Bao (Liberation Army Daily) as a guide for the cadres and fighters of the PLA in their study of Mao’s work, FLP, Peking, 1968, 36 pages.

Preface and Postscripts to Rural Surveys, FLP, Peking, 1966, 8 pages.

Written by Chairman Mao in 1941 in an effort to encourage Party comrades to understand the contemporary situation rather than get caught in thinking that matters don’t change.

A Single Spark can start a Prairie Fire, FLP, Peking, 1966, 18 pages.

Even when is looks like there are so many problems surrounding us that a revolutionary change is impossible we have to remember from a small acorn a mighty oak can grow – all it needs is the right conditions – and under capitalism those conditions are created by the next crisis around the corner!

Chairman Mao Tse-tung’s important talks with guests from Asia, Africa and Latin America, FLP, Peking, 1966, 9 pages.

In May and June 1960 in Tsinan, Chengchow, Wuhan and Shanghai, Chairman Mao received delegations and other friends from the countries and regions in Latin America and Africa and from Japan, Iraq, Iran and Cyprus, who were then visiting China.

Current Problems of Tactics in the Anti-Japanese United Front, FLP, Peking, 1966, 14 pages.

Chairman Mao wrote this outline for a report he made on March 11th 1940 at a meeting of the Party’s senior cadres in Yenan.

For the Mobilization of all the Nation’s Forces for victory in the War of Resistence, FLP, Peking, 1966, 10 pages.

This was an outline for propaganda and agitation written by Chairman Mao on August 25th 1937 for the propaganda organs of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. It was approved by the enlarged meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee at Lochuan, northern Shensi.

On the question of Agricultural Co-operation, FLP, Peking, 1966, 36 pages.

This was a report delivered by Chairman Mao on July 31st 1955 at a conference of secretaries of provincial, municipal and autonomous regional committees of the Communist Party of China.

Talk with the American Correspondent Anna Louise Strong, FLP, Peking, 1967, 8 pages.

Two conversations of Chairman Mao with an American journalist, when the war of liberation against the Japanese invaders had been won and the war against the US/UK /Western imperialist war was taking place against the Kuomintang – the US puppets of what became Taiwan – was still in full force. She was a true friend or revolutionary China and wrote many books to this effect.

The Orientation of the Youth Movement, FLP, Peking, 1967, 16 pages.

This was a speech delivered by the Chairman on May 4th 1939 at a mass meeting of youth in Yenan to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the May 4th Movement. It represented a development in his ideas on the question of the Chinese Revolution.

Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society, FLP, Peking, 1967, 13 pages.

ALL revolutionary movements, whatever country or epoch, need to understand the society in which they are working. A knowledge and understanding of the balance of class forces is vital for the success, or failure, of the revolution.

Why is it Red Political Power can exist in China? FLP, Peking, 1967, 15 pages.

This article was part of the resolution, originally entitled ‘The Political Problems and the Tasks of the Border Area Party Organization’, which was drafted by Comrade Mao Tse-tung on October 5, 1928 for the Second Party Congress of the Hunan-Kiangsi Border Area.

On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship, FLP, Peking, 1967, 21 pages.

This article was written on June 30th 1949 to commemorate the twenty-eighth anniversary of the Communist Party of China.

To be attacked by the enemy is not a bad thing but a good thing, FLP, Peking, 1967, 5 pages.

To be attacked by the enemy is not a bad thing but a good thing.

You know when you are following a correct line when the capitalist and imperialist attack your policies.

Three fundamental articles, FLP, Peking, 1967, 12 pages.

Three revolutionary ‘parables’;

Serve the people

In memory of Norman Bethune

The foolish old man who removed the mountains.

Urgent Tasks following the Establishment of Kuomintang-Communist Co-operation, FLP, Peking, 1968, 16 pages.

The need for China to resolve internal differences in order to present a United Front against the principal enemy, the Japanese imperialist aggressors

Win the masses in their millions for the Anti-Japanese National United Front, FLP, Peking, 1968, 14 pages.

This was the concluding speech made by Chairman Mao at the National Conference of the Communist Party of China held in May 1937.

People of the world unite and defeat the US aggressors and all their running dogs

A call by the Chairman for the people of the world to stand up against US imperialism. As valid now as when it was written. Published as a supplement to the weekly political and informative magazine ‘Peking Review’.

People of the world unite and defeat the US aggressors and all their running dogs Published in China Reconstructs, 1970, No. 5, Supplement No. 2.

Marxism and the Liberation of Women, Quotations from Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, VI Lenin, Joseph Stalin and Mao Tse-tung, Union of Women for Liberation, London, n.d., mid-1970s?, 64 pages. Includes a statement of aims of the Union of Women for Liberation.

Record of the Conversation from Chairman Mao’s Audience with the Albanian Women’s Delegation and Albanian Film Workers, May 15 1964, Wilson Centre Digital Archive, ND, 7 pages.

On the Communist Press, Lenin, Stalin and Mao Tsetung, Canadian Communist League (Marxist-Leninist), n.d., 200 pages.

Talk at an Enlarged Working Conference convened by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, January 30, 1962, 17 pages. From Peking Review, No. 27, 1978. This very important speech was given at what was informally known as the ‘Seven Thousand Cadres Conference’. It addresses questions such as promoting democracy among the masses and within the Party.

Record of conversation between Soviet Ambassador in China, Apollon Petrov, and Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and Wang Ruofei, October 10, 1945, Wilson Center, translated from Russian into English, 4 pages.

Mao’s remarks at the banquet for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Delegation, November 23, 1953, Wilson Center Digital Archive, 2 pages.

Minutes of Mao’s Conversation with a Yugoslavian Communist Union Delegation, Beijing, not dated but in September 1956, Wilson Center Digital Archive, English translation from a Chinese historical archive of ‘Selected Diplomatic Papers of Mao Zedong’, 8 pages. Comments by Mao, apologizing to the Yugoslavians for their treatment by both Stalin and China during the late 1940s period, with an extensive criticism of Stalin with regard to the Chinese Revolution, and an explanation as to why China had so far not been more publicly critical of Stalin. But soon after Tito moved to a repudiation of Socialism followed by the all round restoration of capitalism in the USSR.

Mao’s Conversation with Albanian Comrades Hysni Kapo and Beqir Balluku, February 3, 1967, Wilson Center Digital Archive, 11 pages.

Directives from Chairman Mao’s commentary on the Water Margin and his critique of capitulationists, August 18, 1975, 4 pages.

Comrade Mao Tse-tung on Imperialism and All Reactionaries are Paper Tigers, Editorial Department of Renmin Ribao (People’s Daily), October 27, 1958. FLP, Peking, 1966, 3rd ed., 2nd revised translation, 34 pages.

The works of Chairman Mao in languages other than English

The writings of Chairman Mao Tse-tung were produced in many different languages. Here we present a few in Spanish.

Citas del Presidente Mao Tse-tung, Ediciones en Lenguas Extanjeras, Pekin, 1967, 208 pages.

‘El pequeño libro rojo’ de citas de las obras del Presidente Mao Tse-tung.

Comentarios sobre el Manual de Economia Politica Sovietico, Lima SA, Peru, ND, 166 pages.

Los comentarios del Presidente Mao sobre el Manual de Economía Política Soviético (un libro de texto por Comunistas) y sobre el libro Problemas Económicos del Socialismo en la URSS de José Stalin.

La guerra de guerrillas, Editorial Huemul, Buenos Aires, 1973, 91 pages.

Un pequeño libro con los principios fundamentales de La guerra de guerrillas, originalmente publicada en 1937.

Cinco Tésis Filosòficas, Lima, Peru, ND, 112 pages.

Sobre la Práctica

Sobre la Contradicción

Sobre el tratamiento correcto de las contradicciones en el seno del pueblo

Discurso ante la conferencia nacional del PCP sobre el trabajo de propaganda

¿De dónde provienen las ideas correctas?

The death of Chairman Mao Tse-tung

The edition of Peking Review that announced the death of Comrade Mao Tse-tung, Peking Review, No 38, 1976.

Eternal Glory to the Great Leader and Teacher Chairman Mao Tse-tung, FLP, Peking, 1976, 40 pages.

Memorial speech by Hua Kuo-feng and the decision to construct the memorial hall in Tien an Men Square, Peking.

Contemporary Translations and Commentaries

Chairman Mao’s Primary Directives, Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: Document 4 (1976), issued by the General Office of the Central Committee, March 3, 1976, 2 pages. Includes critical comments by Mao on Deng Xiaoping and his associates.

Mao’s Talk with Members of the Politburo who were in Peking, May 3, 1975 – with extensive notes and context information added, 15 pages.

The early revolutionary activities of Comrade Mao Tse-tung, Li Jui, White Plains, NY, 1977, 404 pages. This is the English translation of the Chinese edition published in Peking in 1957. It has some underlining.

Mao Tse-tung, Ch’en Po-ta, and the conscious creation of ‘Mao Tse-tung’s Thought’ in the Chinese Communist Party, 1935-1945, Ph.D. thesis by Raymond Finlay Wylie, University of London, February 1976, 415 pages.

Private Writer vs. Private Doctor, a very critical review by Mao’s former close secretary and aide, Qi Benyu, of the outrageously slanderous and fraudulent book, The Private Life of Chairman Mao,1994, written by one of Mao’s former doctors, Li Zhisui. 18 pages.

Egalitarian inventions and political symptoms: a reassessment of Mao’s statements on the ‘Probable Defeat’ of Socialism in China, Alessandro Russo, Crisis and Critique magazine, volume 3, No. 1, 2016, 22 pages.