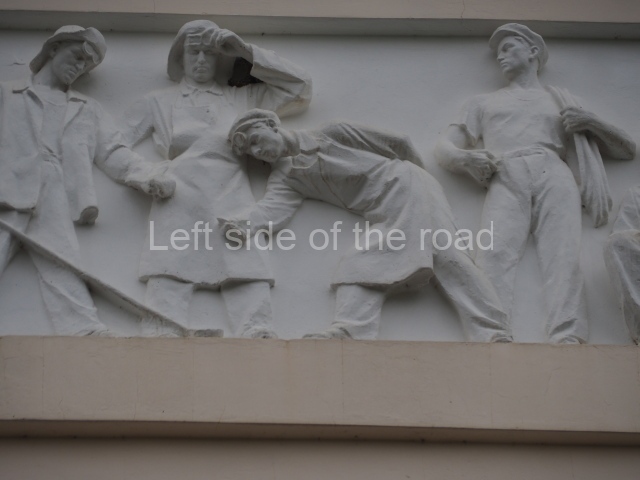

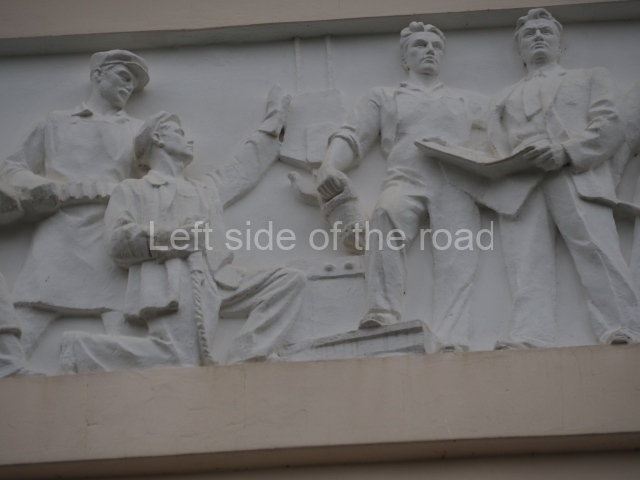

We are together in the fight against fascism

This particular sculpture, impressive as it is, poses and challenge to me when being asked ‘What is a piece of Socialist Realist art?’ Art can be realist without having any reference to socialism even though it might represent a worker or workers sympathetically. But what takes one piece of work from a mere representation of a person or an event to a different level, to imbue it with a meaning that is over and above what is merely in front of the viewer.

My simple interpretation of that has been the intention of the artist at the time of the work’s creation, the intended audience and what was hoped would be achieved by it’s presentation to the public. But these intentions and hopes are not concrete. They can exist in one period of time but can just disappear if (and unfortunately) or when the social system reverts to what it was pre-Revolution – as happened in the Soviet Union (and all the other post-Socialist societies).

But if, as it did, Revisionism took control soon after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 can those works of art produced after that date until 1991 still be considered works of Socialist Realism? They were still produced for the same audience as were the target in the 1930s and 1940s but for a different purpose, after the mid-50s the aim was to project an image of being in favour of revolutionary change whilst at the same time doing everything practically to avoid such a transformation occurring.

The history (or more accurately to say, its genesis) of this particular monument is quite unique and exceptional, fitting in more with the political agenda of the Russian Government at the time rather than a desire to remind future generations of the sacrifice made by those during the Great Patriotic War or the desire to foment a willingness of self sacrifice amongst a population who are attempting to build Socialism.

On 19th December 2009 a Soviet era monument, the Kutaisi Glory Memorial, which had been unveiled in 1981, was blown up by Georgian fascists under the cloak of ‘nationalism’ and ‘reconstruction’ of the city. The location of the monument was to be the site of the new Parliament building.

The original plan was for the monument to be destroyed on 21st December (coincidentally the anniversary of Stalin’s birth) and a mass demonstration had been planned to oppose this desecration of the memory of all those Soviet citizens (including those from Georgia) who had died in the fight against fascism. The decision the destruction should take place two days earlier than originally planned is considered to have made to circumvent any opposition. Because the task was rushed it was botched with pieces of concrete flying all over the place, some of it killing a woman and her eight year old daughter who lived close by.

But the destruction of this monument also has to be taken in the context of what was happening in the region at the time. This was just after the short war between Russia and Georgia, in 2008, over the separatist regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia – one started by Georgia under the encouragement of the US. This was all part of a strategy to surround (with hostile NATO states) and eventually dismember the Russian Federation – which had been the intention of the neo-liberals in the west since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

For that reason the demolition of the memorial was more than an attack on the memory of all those who died fighting fascism it was part of the present war against Russia. This created a sense of urgency, an advert for the commission was circulated and by July 2009 there were already six maquettes of the proposed statue to be erected on a site in Park Pobeda (Victory Park) in Moscow. These designs were on display in the Great Patriotic War Museum, awaiting a popular vote.

At the same time the maquettes were on display in Moscow Hilary Clinton was visiting Tbilisi, adding fuel to the conflict and mouthing her meaningless phrases about the US in support of national liberation of those countries ‘occupied’ and vowing never ending US support for ‘the fight for freedom’. Similar declarations, before and subsequently, ultimately led to the situation we have in the Ukraine at the moment and have led to continued efforts by the US to destabilise other countries in eastern Europe – cut short recently by Trump’s rethink on how to allocate resources to maintain the US’s ‘full spectrum dominance’ in the region.

So a somewhat unique genesis of a World War II monument.

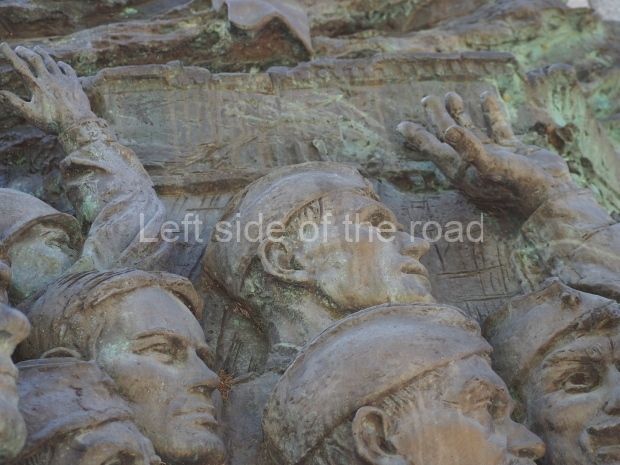

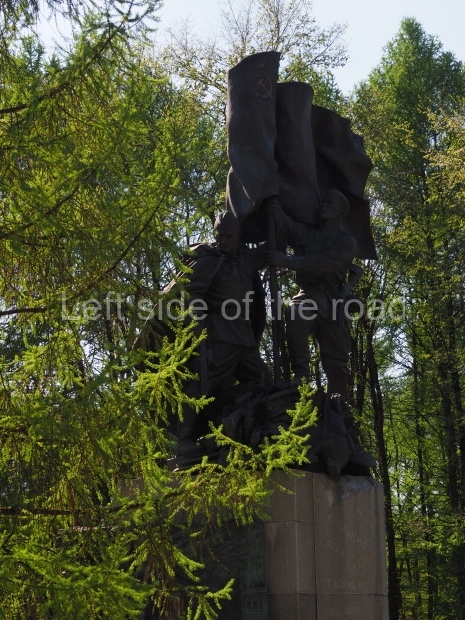

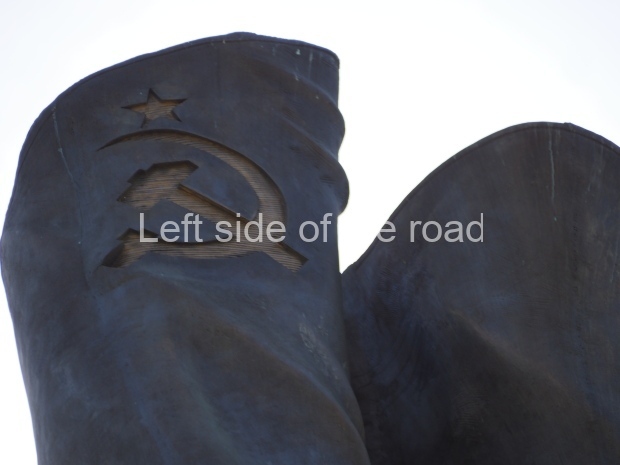

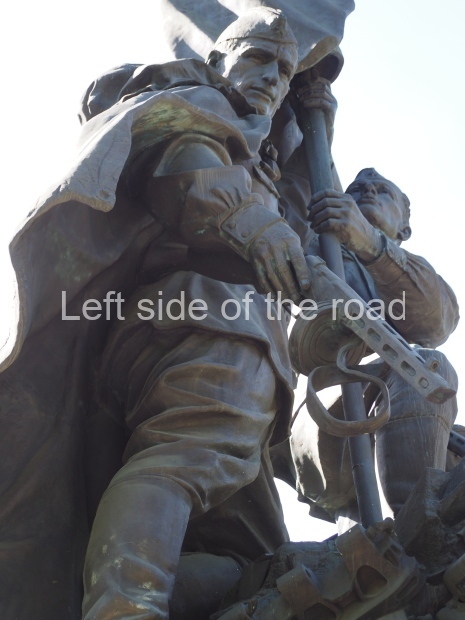

The design of the monument follows many, well established tropes for such statues. In general it depicts the events surrounding the Fall of Berlin, the occupation of the fascist liar by Soviet troops, the raising of the Red Flag over the Reichstag and the first ever Victory Day Parade in Red Square in Moscow.

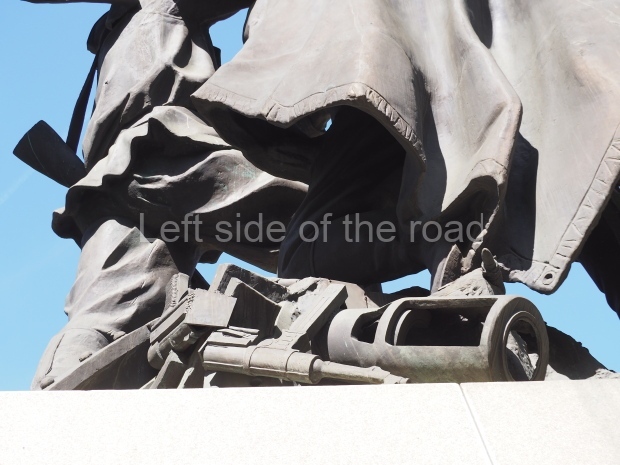

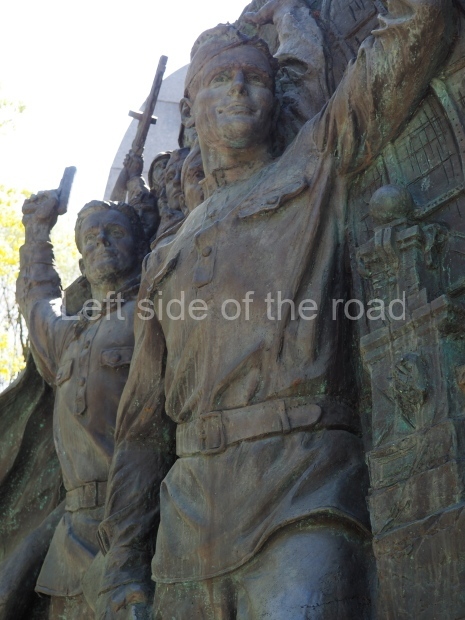

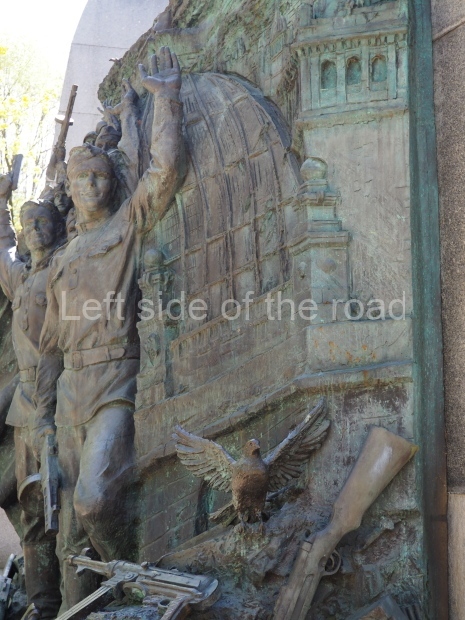

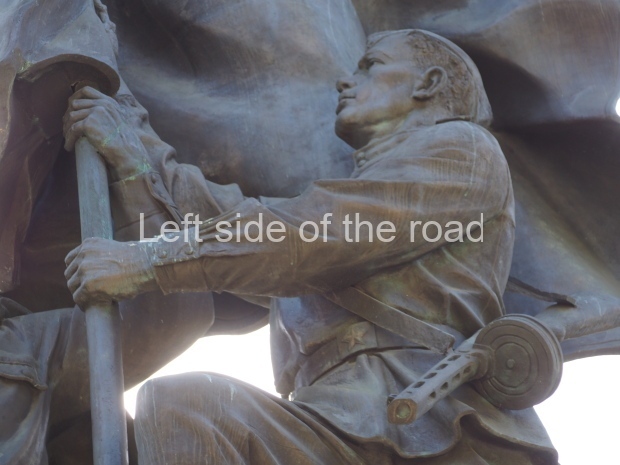

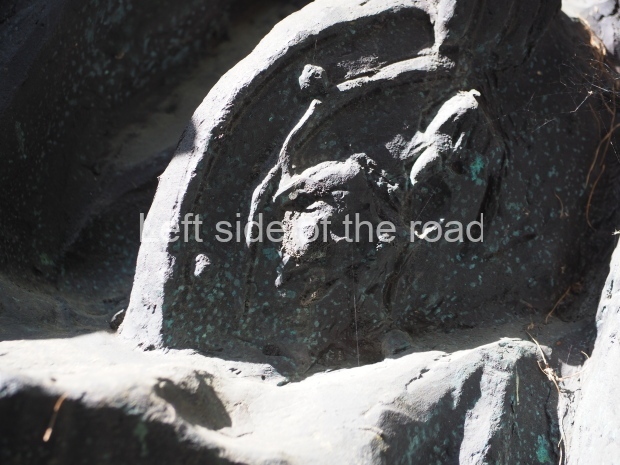

A common theme of the three, separate components of the statue is the dominance of Soviet over Nazi weaponry, imagery and culture. At the very top two Soviet soldiers are in the process of raising the Red Flag, one of the soldiers pointing his weapon at the pile of German weapons that lay discarded on the ground. Amongst this pile of weapons and debris is a toppled German eagle. We’ve won, you’ve lost!

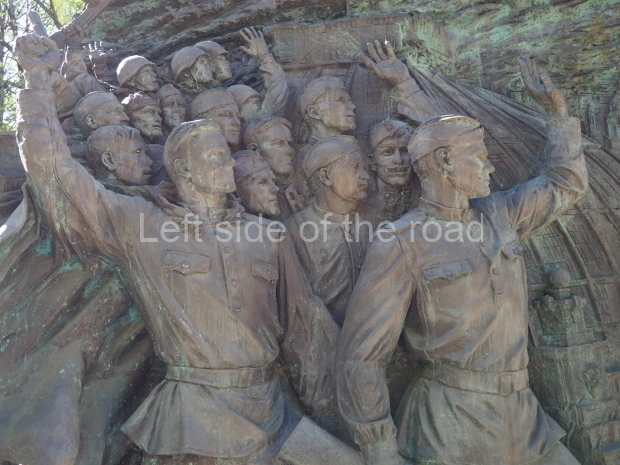

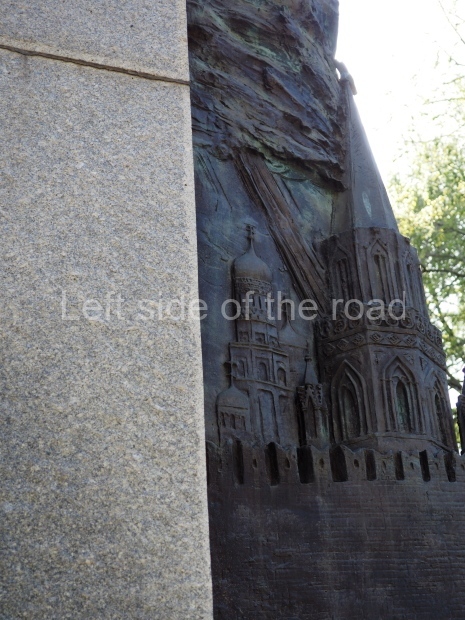

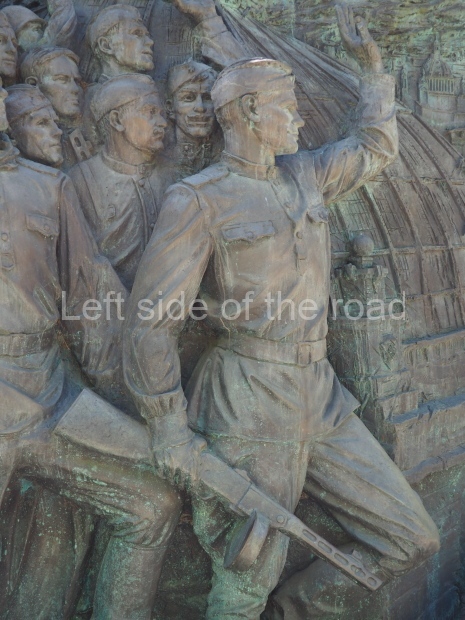

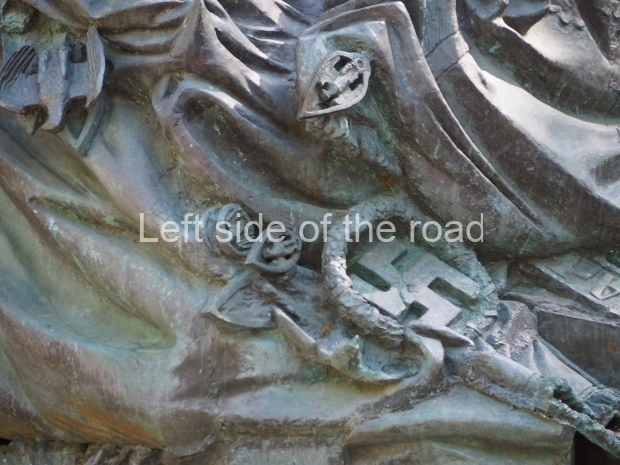

On the left hand side we have a group of Soviet soldiers who are greeting others, unseen, as they stand beside the burnt out dome of the Reichstag building. Under their feet and before them, discarded on the ground, are Nazi weapons, ruined machinery, barbed wire, destroyed Nazi standards (with the swastika broken) and on top of all this detritus a dove of peace is in the process of alighting.

On the right hand side we have the depiction (the only example I’ve seen in a monumental form) of an episode that took place during the first Victory Parade where Soviet solders entered Red Square with dozens of captured Nazi banners, marched to the Lenin Mausoleum, upon which Comrade Stalin and other members of the Soviet leadership were standing to review the parade, and there the troops threw the Nazi standards down into the mud at the door of Lenin’s resting place. In the background of the monument can be seen the Spasskaya Tower and the building that used to be the Lenin Museum but which is now the Museum of the Patriotic War of 1812.

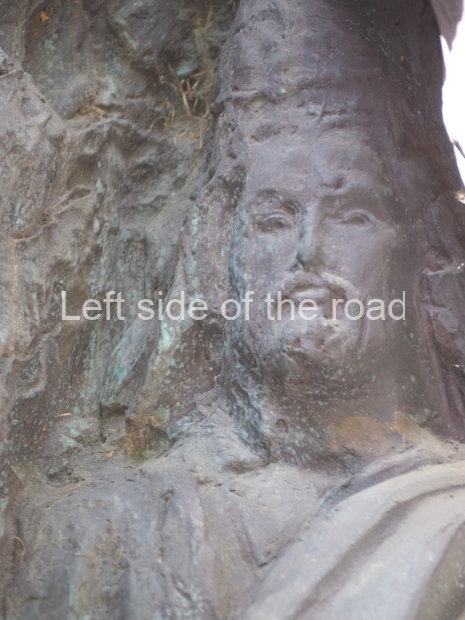

However, there are two aspects which differentiate this monument from those that would have been created even in the Revisionist period of the Soviet Union. And both these are on the right hand side. Amongst the group of soldiers cheering there is one face that is looking out directly at the viewer whilst all the rest are looking to the front. Also, tucked behind the folds of the flag on that side is an incongruous figure on a horse. This figure is long haired and bearded and is totally out of place. A Christ figure? And I couldn’t work out what he has in his hand.

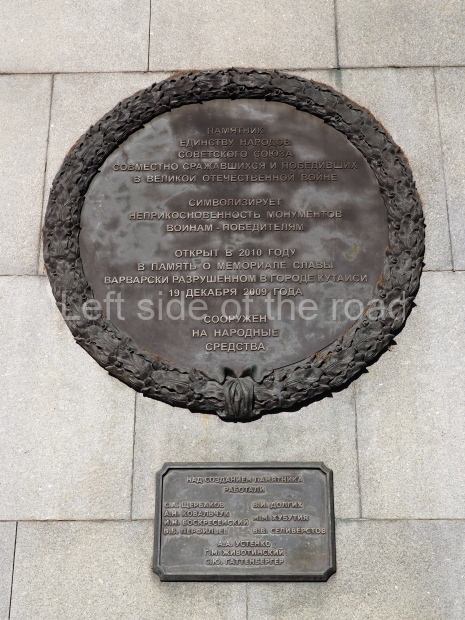

At the rear of the monument are two plaques. One explaining the reason for its existence and the other with the names of those involved in its creation.

Translation of the plaques on the rear of the monument. (Machine translated so apologies for any eccentricities.)

Monument to the Unity of the Peoples of the Soviet Union who fought and won together in the Great Patriotic War.

Symbolising the inviolability of monuments to victorious soldiers

It was opened in 2010 in memory of the Glory Memorial which was barbarously destroyed in the city of Kutaisi on December 19, 2009

Built with folk remedies

Sculptors/Architects; – the names listed. However, I don’t know the exact level of their involvement but assume that Shcherbakov was the principal sculptor.

S A Shcherbakov

A N Kovalchuk

I N Voskresenskiy

B V Perfiliev

V V Seliverstov

A A Ustenko

E H Zhivotinsky

G J Gattenberger

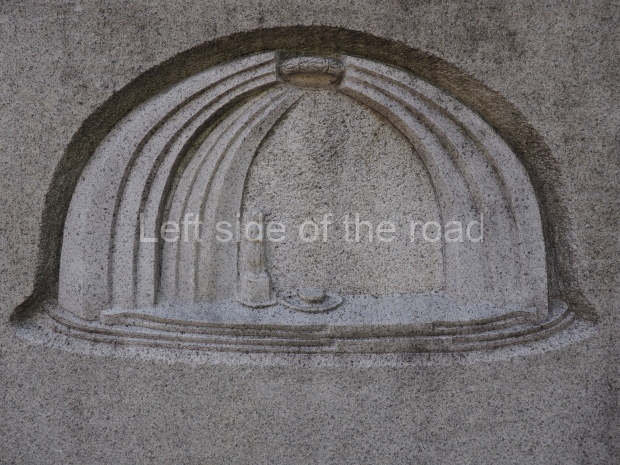

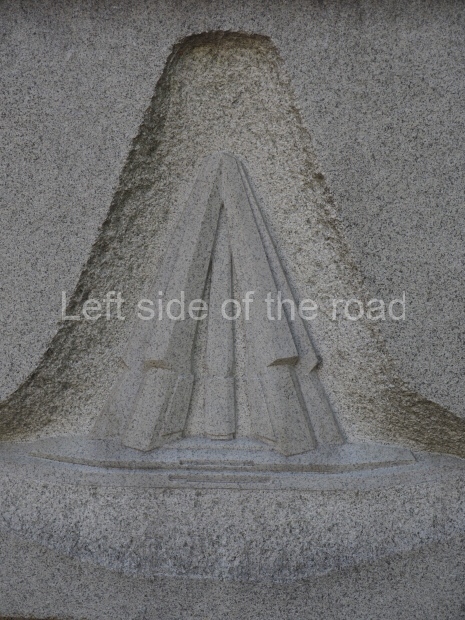

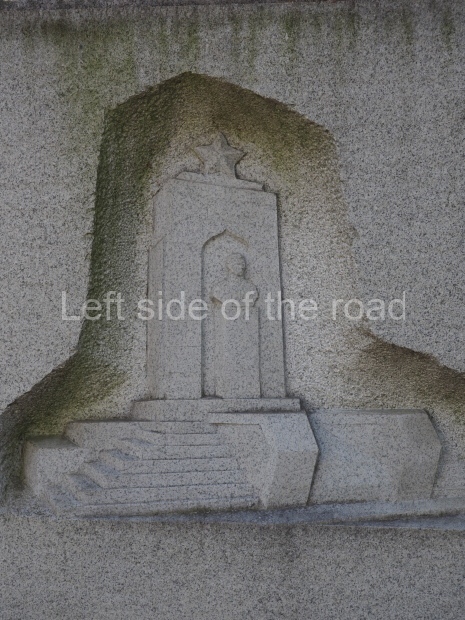

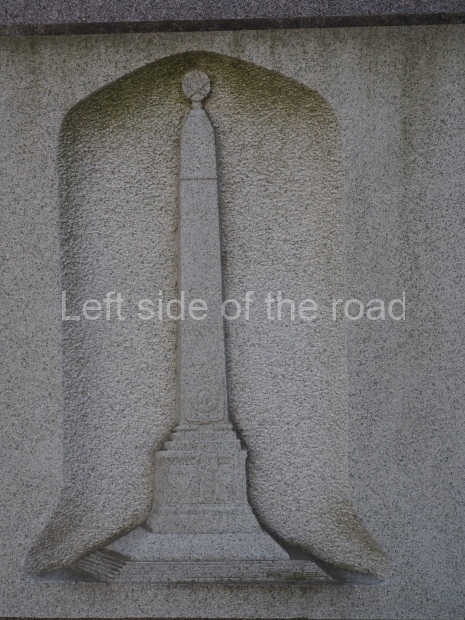

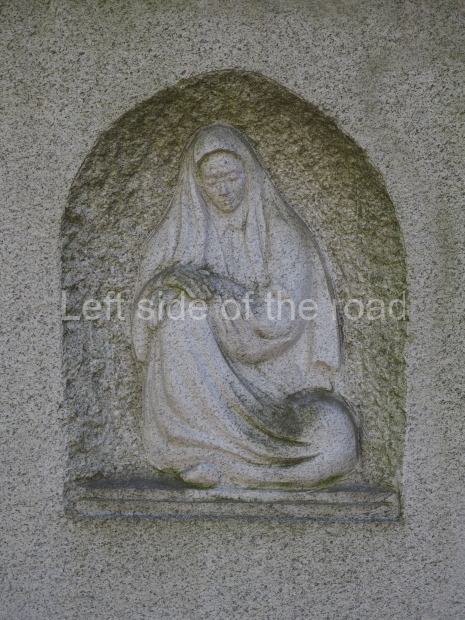

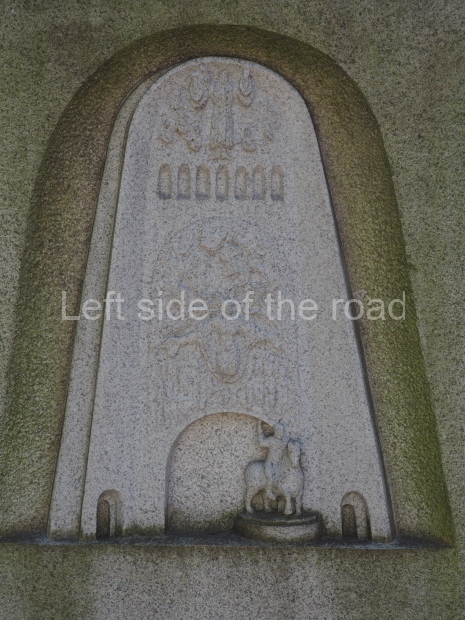

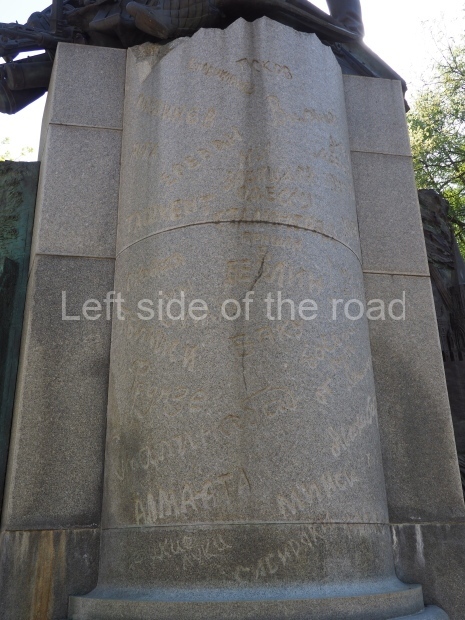

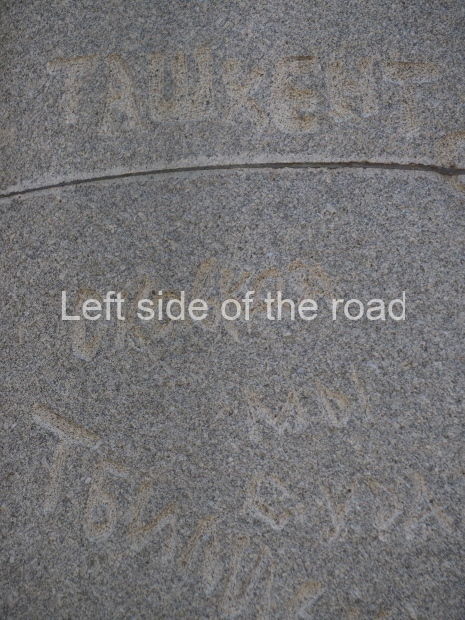

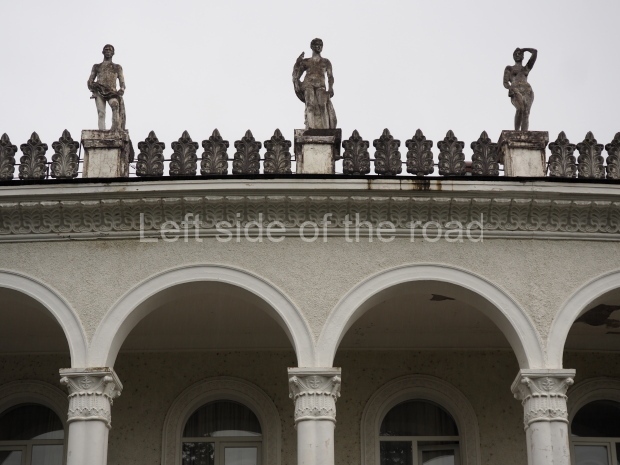

In the centre of the concave, stone wall set back a few metres from the statue the high structure pays homage to the monument that was blown up in Tbilisi. The large letters (in Russian) declare the name of the ensemble – ‘We are together in the fight against fascism’. Lower down and on either side are smaller images of other memorials from other Soviet Republics. I can identify Mother Armenia in Yerevan, the original monument in Kutaisi and the Motherland Calls! in Stalingrad but have problems with the others.

On either side of the installation stand two pillars upon which is place a horizontal, large, golden star.

Closest public transport;

Park Pobeda Metro station

Location;

In Victory Park (Park Pobeda), Moscow

GPS;

55.72845 N

37.50152 E

How to get there:

From the metro station head towards the obelisk and main museum but take a path off to the left which goes beside the church. Keep on this track as it goes past the entrance to the Military Weapons Museum (on your left) and then rises as it skirts around the left of the principal, circular structure. The monument is on the left hand side of the track.