House at Kaspi Street 7

More on the Republic of Georgia

Bolshevik Illegal Printing Press – Tbilisi

You have to admire the work that was expended and the organisation needed to construct the room and infrastructure for the illegal printing press that the Tbilisi (Tiflis) branch of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (which, after the October Revolution of 1917, eventually became the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolshevik)) created in the first years of the 20th century.

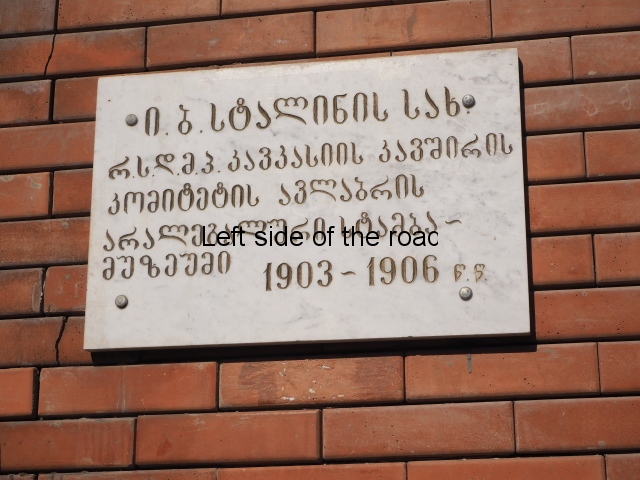

There’s a number of things to admire about this project that was in revolutionary use between November 1903 and April 1906.

First it was obviously a well thought through and planned project. The Georgian revolutionaries needed a printing press, they needed it well hidden from the Okhrana – the Tsarist ‘secret’ police – and they needed it to be open enough to allow the constant comings and goings that would be necessary for the printing and distribution of thousands of leaflets and pamphlets needed to spread the word of the young, revolutionary Marxist organisation in Georgia.

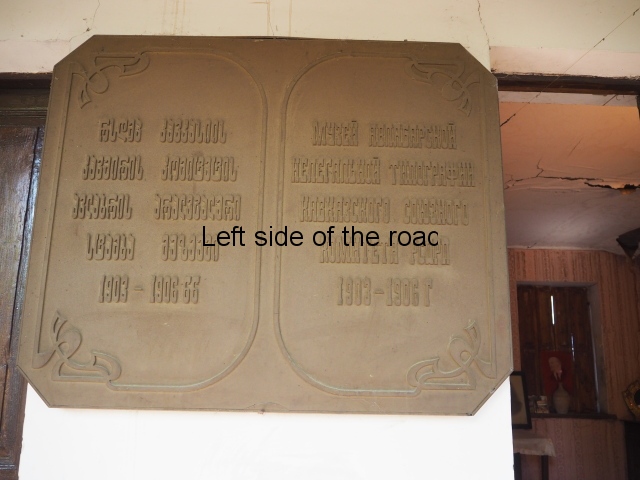

One remarkably bold enterprise of the Caucasian Union of the R.S.D.L.P., and an outstanding example of the Bolshevik technique of underground work, was the Avlabar secret printing press, which functioned in Tiflis from November 1903 to April 1906. On this press were printed Lenin’s ‘The Revolutionary Democratic Dictatorship of the Proletariat and the Peasantry’ and ‘To the Rural Poor’, Stalin’s ‘Briefly About the Disagreements in the Party’, ‘Two Clashes’ and other pamphlets, the Party program and rules, and scores of leaflets, many of which were written by Stalin. On it, too, were printed the newspapers Proletariatis Brdzola (The Proletarian Struggle) and Proletariaiis Brdzolis Purtseli (Herald of the Proletarian Struggle). Books, pamphlets, newspapers and leaflets were published in three languages and were printed in several thousands of copies.

A decisive role in the defence of the principles of Bolshevism in the Caucasus and in the propagation and development of Lenin’s ideas was played by the newspaper Proletariatis Brdzola, edited by Stalin, the organ of the Caucasian Union of the R.S.D.L.P. and a worthy successor of Brdzola. For its size and its quality as a Bolshevik newspaper, Proletariatis Brdzola was second only to Proletary, the Central Organ of the Party, edited by Lenin. Practically every issue carried articles by Lenin, reprinted from the Proletary. Many highly important articles were written by Stalin. In them he stands forth as a talented controversialist, eminent Party writer and theoretician, political leader of the proletariat, and faithful follower of Lenin. In his articles and pamphlets, Stalin worked out a number of theoretical and political problems. He disclosed the ideological fallacies of the anti-Bolshevik trends and factions, their opportunism and treachery. Every blow at the enemy struck with telling effect. Lenin paid glowing tribute to Proletariotis Brdzola, to its Marxian consistency and high literary merit.

(Joseph Stalin – a short biography, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1949, pp20-21.)

Second it needed meticulous organisation, the involvement of many people with different skills and abilities and – perhaps most important of all – a revolutionary unity and confidence which kept the real intention of the project away from an all pervasive and vicious secret police known to depend upon traitors, collaborators and agent-provocateurs to achieve their aims. And that’s just for the building of the structure.

There’s no way that the press could have been installed after the construction of the building itself – a large house that would have been on the edge of the town of Tiflis (now Tbilisi). The very complicated nature of access and also the size and location of the room with the printing press (as well as the printing press itself) meant that the space had to have been excavated under the cover of constructing the building’s cellar.

The extra work needed for the illegal aspects of the construction site would have needed to be monitored carefully. The building workers were almost building two buildings under the pretence of one but they would have had to have completed the work in the normal time it would have taken to construct one such house – otherwise people would have started to ask questions and suspicion would have been aroused, especially in a predominantly peasant society.

Third, there would have been the need for an not inconsiderable amount of money for such a large and complicated project – as well as a state of the art lithographic printing press, plus all the paper and materials needed once in operation. We must remember that we are here talking about industrial workers who were barely earning enough to feed themselves and their families. The finances for such a major enterprise would have never have been available without the introduction of finances from other sources. Banks had those finances and they assisted in the development of the revolutionary movement by contributing to the coffers by way of the intermediaries, Comrades Kamo (Simon Petrosian, whose bones you might walk over – between the fountain and the Pushkin bust – on the way to the Tourist Information Centre in Pushkin Park) and Koba (who used to share a room with VI Lenin in Red Square, Moscow, but who now has a niche in the wall of the Kremlin.

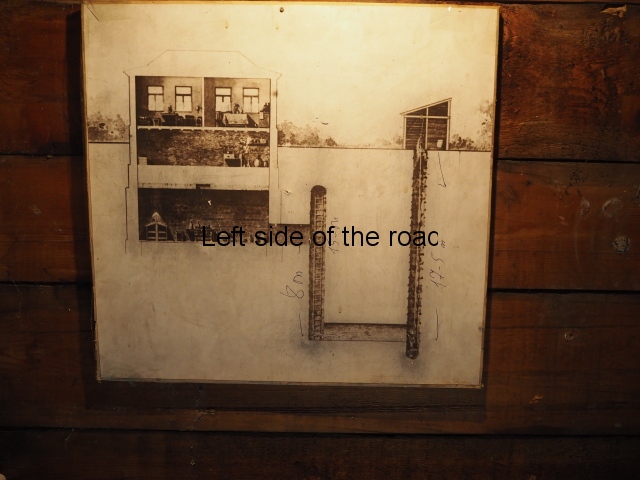

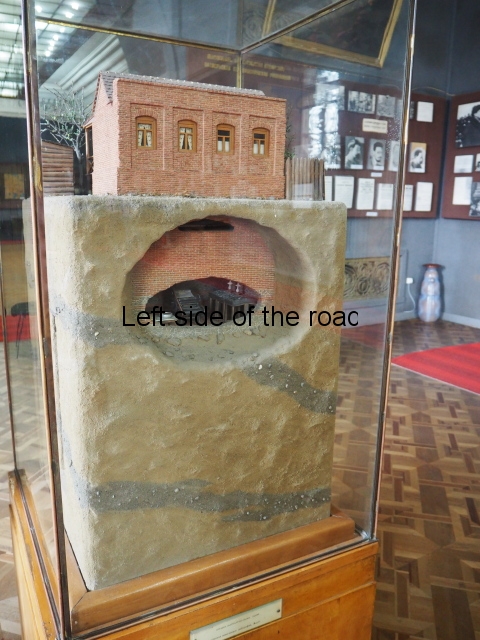

An idea of the complex project

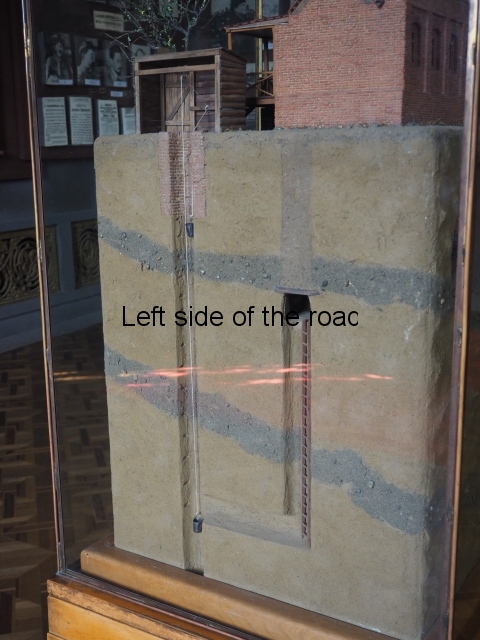

Plan of the project

As can be seen by the plan above there was no direct access to the room of the press from the house. Looking at the diagram it would seem to me that much of the construction of the vaulted room of the press and the tunnels and shafts leading to the well shaft would have used access to what became the cellar/kitchen of the house itself. This would then have been filled in to give the impression of ground level. It’s possible that the present day access to the underground room would have been the place of access at the time of construction. So much soil and rock would have to have been removed that any other manner of excavation seems to hard to make sense.

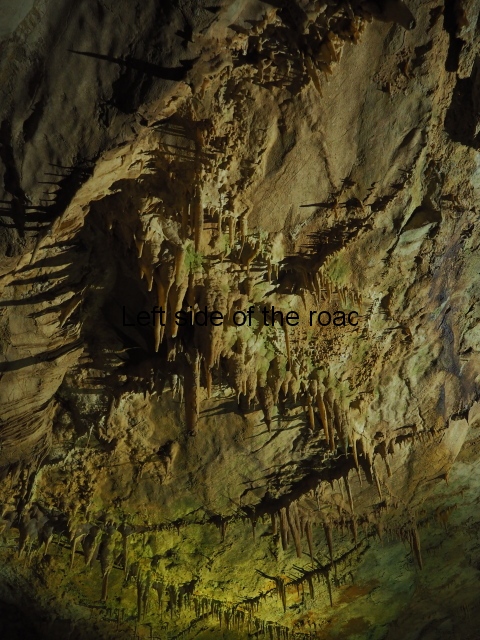

The well and access to the room

The ‘access’ well

Once the building was finished and the press installed the only way to get to it was via the well, covered by a small hut a few metres south-east of the main building. This is a deep well as the builders had to go down more than 18m before reaching the water level. Access down this well would have been by a removable rope, I’m assuming, anything more substantial would have raised suspicions in the event of a raid by the Okhrana.

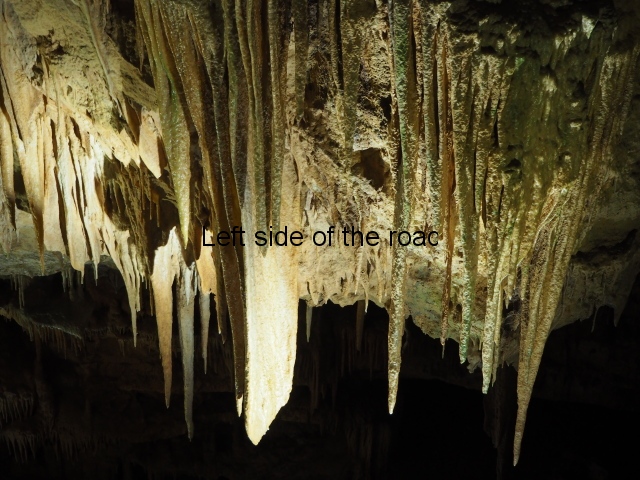

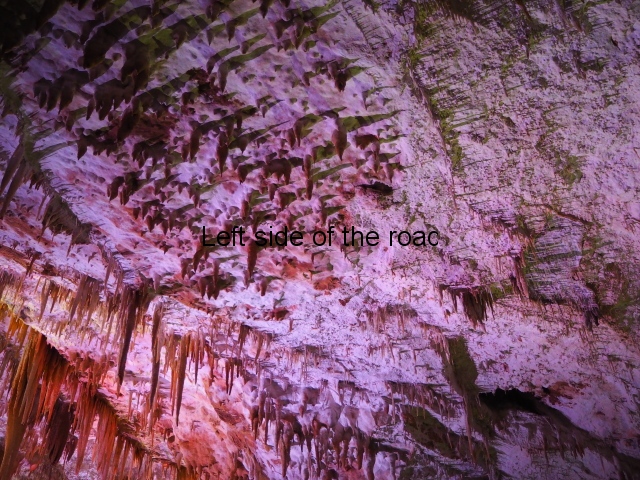

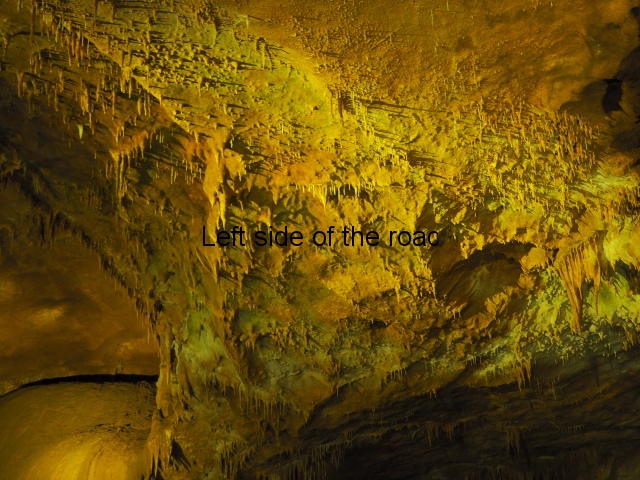

Just before the water level (at 17.5m) a tunnel was constructed at right angles to the shaft, 8m long back towards the building. Then a shaft 15m high was built up towards ground level. At 8m another, short tunnel was constructed to provide access to the underground room itself. (This shaft goes up another 7 or so metres after the tunnel – but I can’t work out why.) Along the whole length of this shaft a ladder was fixed to the wall. Both the tunnels at the top and bottom were high enough for a person to walk through if bent double. Now electric lighting has been installed but, presumably, in the early 20th century the only lighting would have been oil lamps or candles.

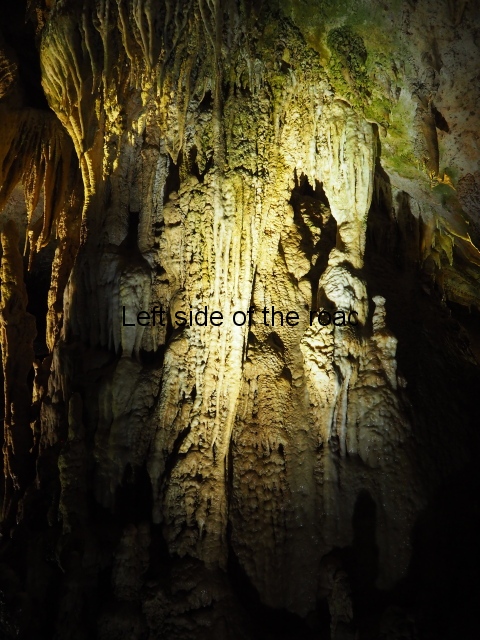

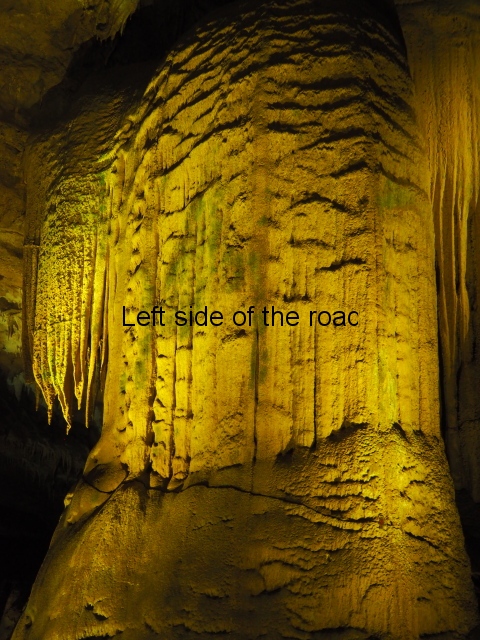

All the tunnels and shafts are brick lined and the tunnels are arched.

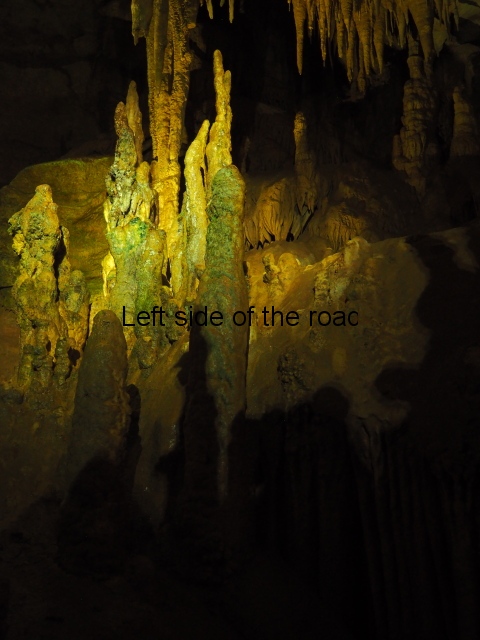

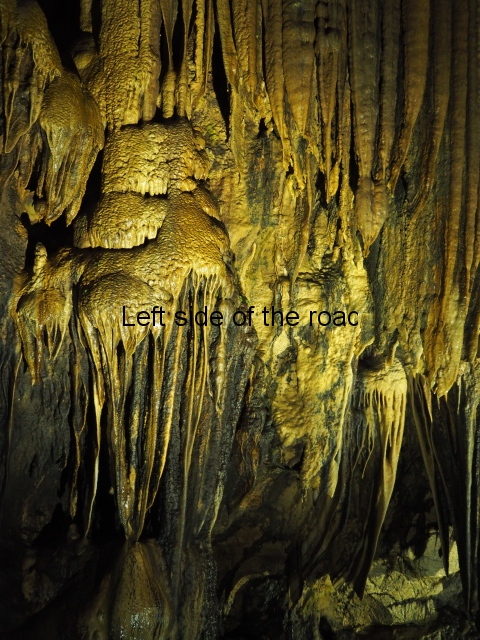

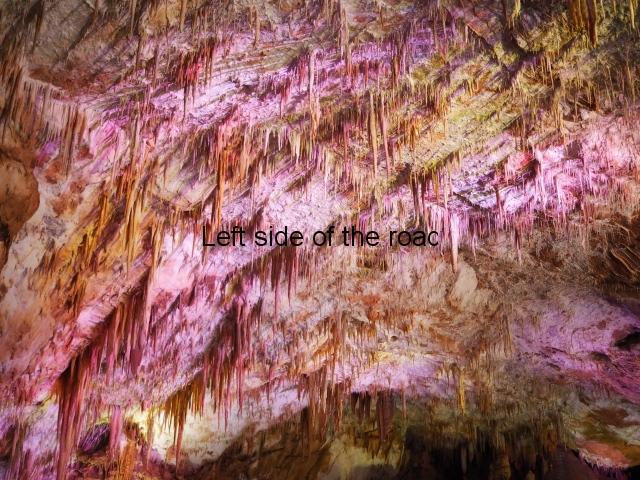

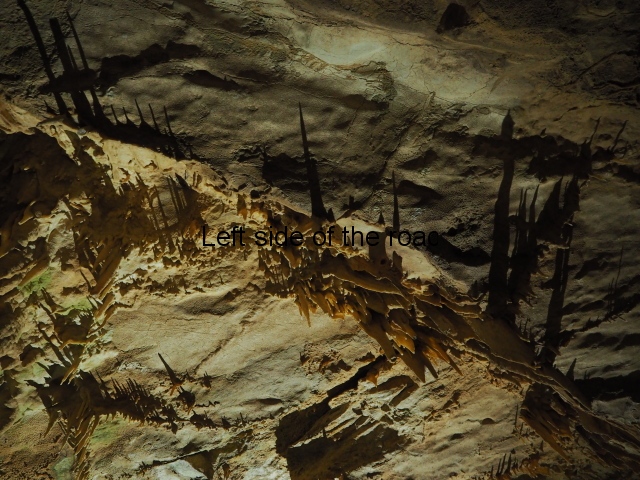

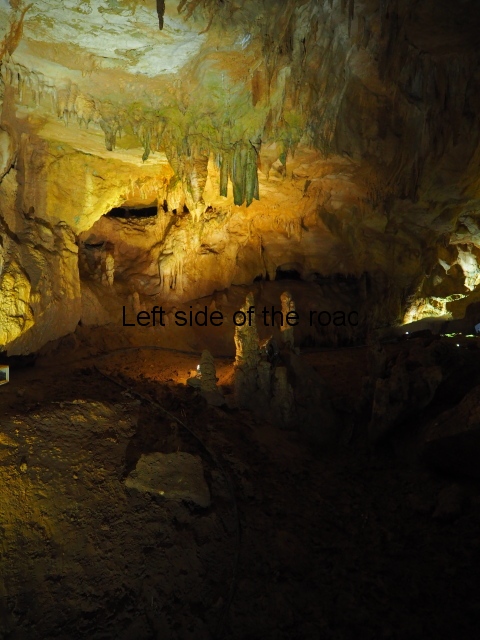

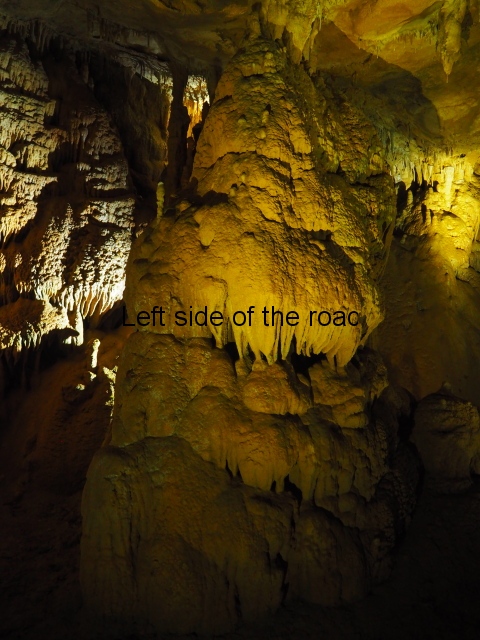

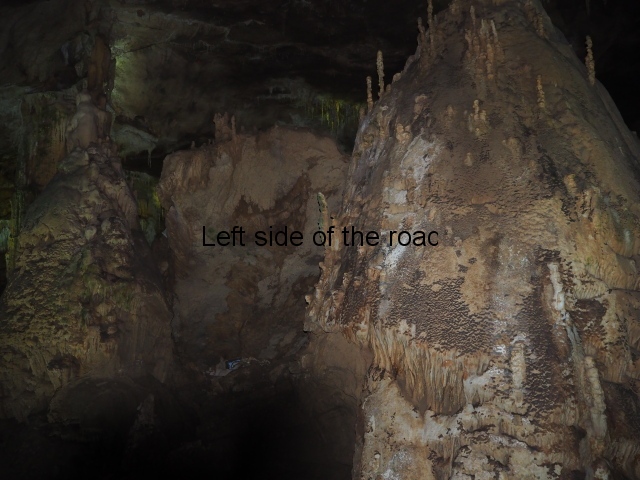

The underground room

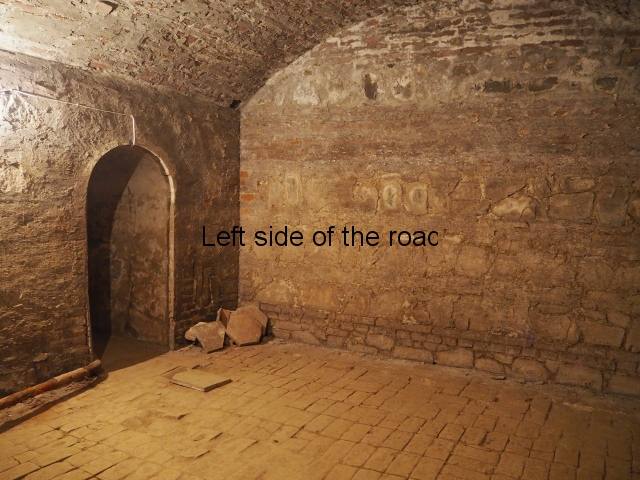

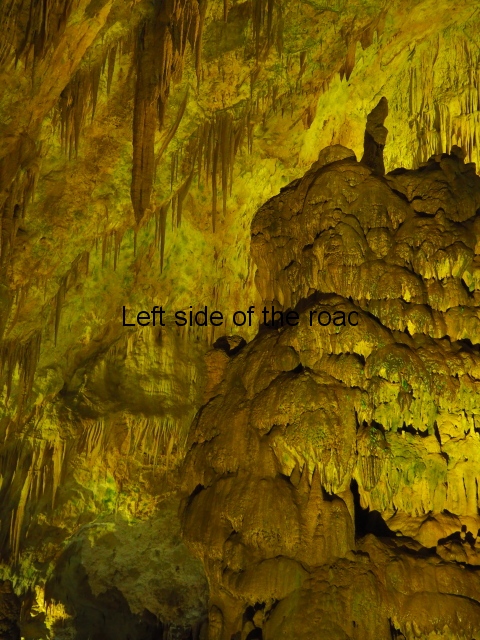

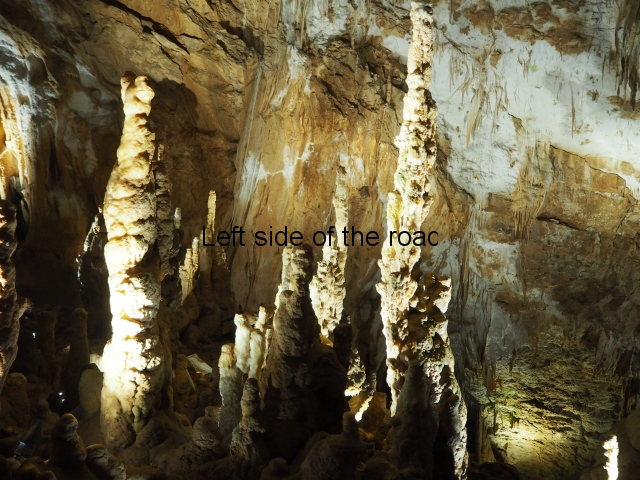

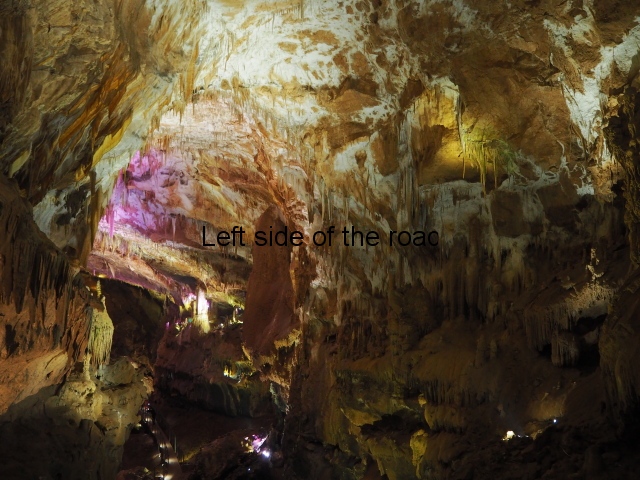

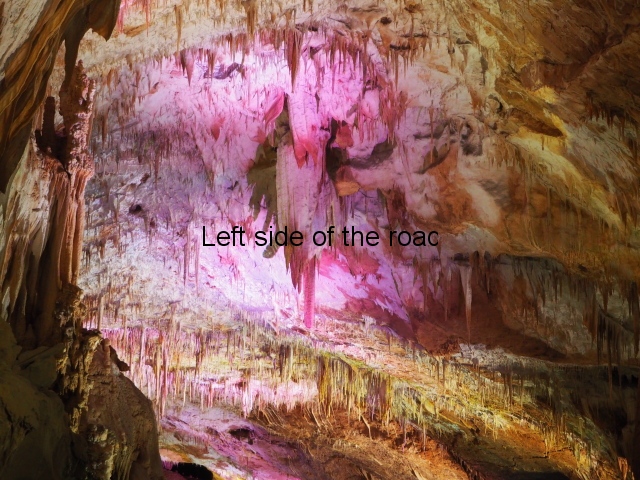

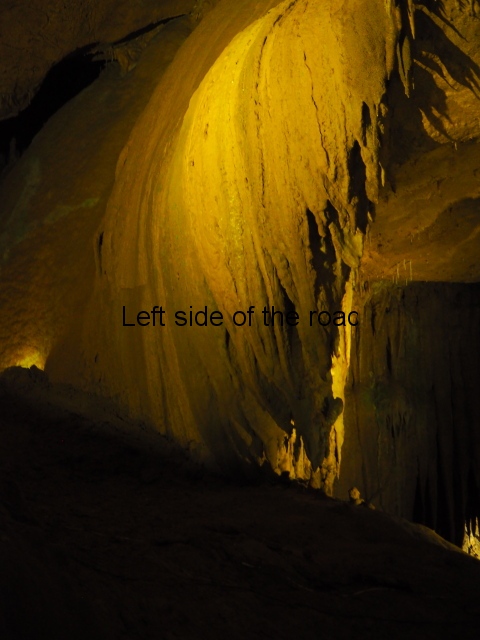

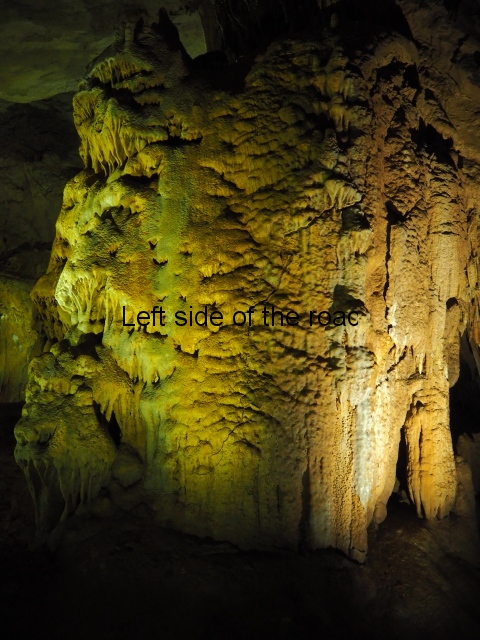

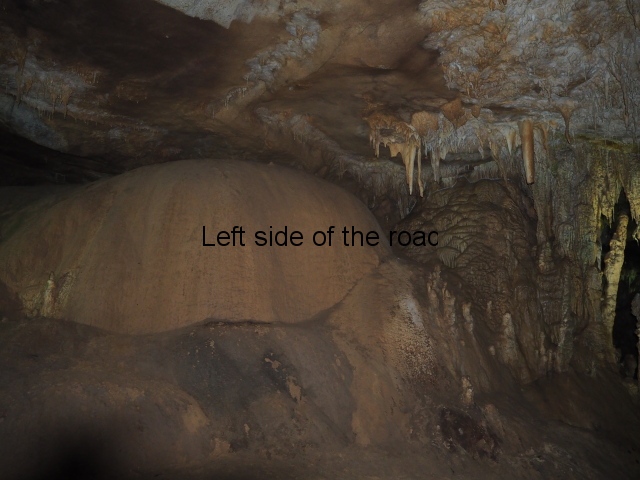

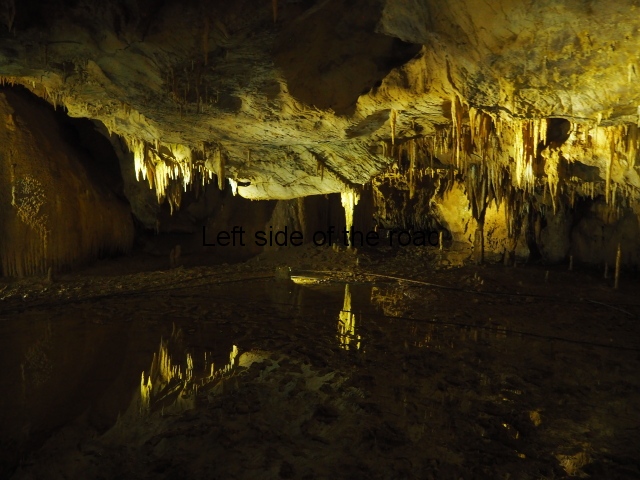

The underground room – looking towards present day entrance

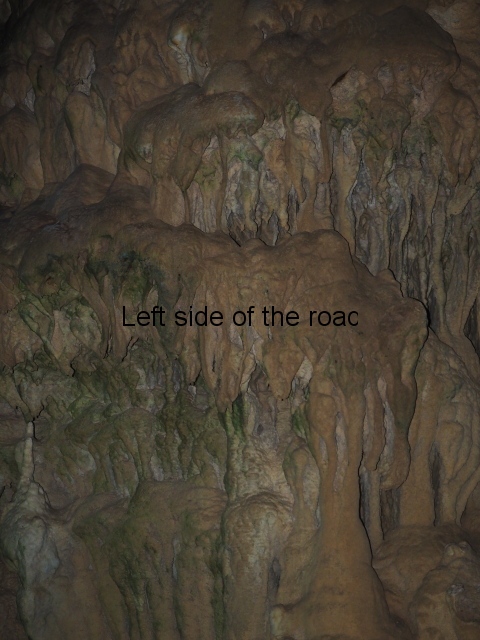

It’s a surprisingly large room if you think of the relatively narrow shafts and tunnels the Georgian Communists would have needed to negotiate to get there before starting work. I estimate the vaulted room to measure, roughly, 11m long, by 4m wide and 4m high – to the apex of the vaulted ceiling. This is large enough not to feel too claustrophobic to someone down there for a few hours.

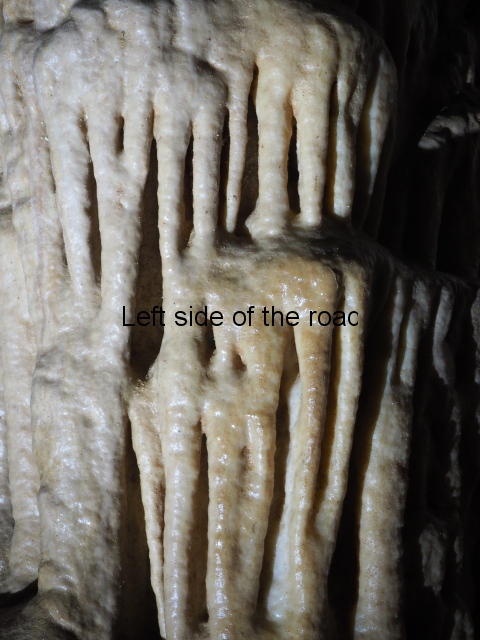

But this isn’t the result of a group of amateurs. This is a well-made, professional construction. The floor is brick lined and the walls alternate with layers of brick and then large stone blocks cemented in place. The ceiling is a brick lined, barrel vault.

All that’s in the room now is a rusting-away, manually operated, lithographic printing press.

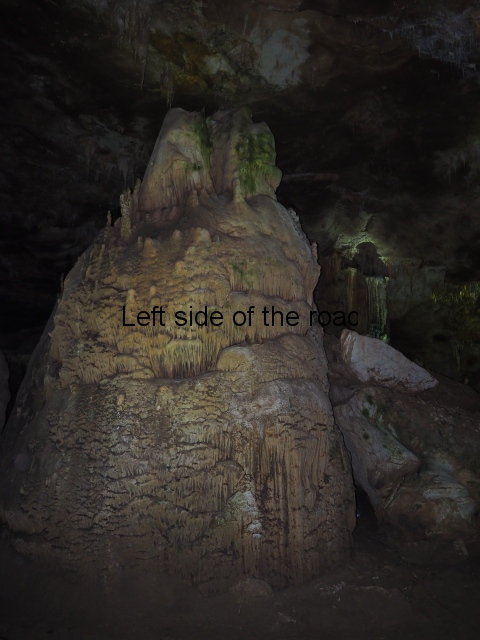

The press with the clandestine entrance

At the height of its use there would have been benches for the preparation of the plates, places for cutting the sheets for leaflets and folding and collating areas for pamphlets. I wouldn’t have thought it would have been possible to produce substantial books given the confines of the location but at the same time this location was constructed for the production of large scale, immediate propaganda and the aim would be to write the text, print and distribute in a relatively short time. More substantial books, such as some of the works of VI Lenin, would have been produced in commercial printing establishments outside of the country and then brought in illegally.

I can’t imagine this would have been the most healthy of places to have worked. Printing inks are, and have always been, quite toxic and there wouldn’t have been a great deal of ventilation in the cellar. I’m not aware of any through draft which could have taken the stale and chemical air out and bring fresh air in. The construction of a shaft to the ground above would have created a security threat as if stale air had a way to escape then so would noise.

Structurally, the tunnels, shafts and the room itself seem to be in remarkably good condition considering they have been neglected for most of the 117 years of their existence.

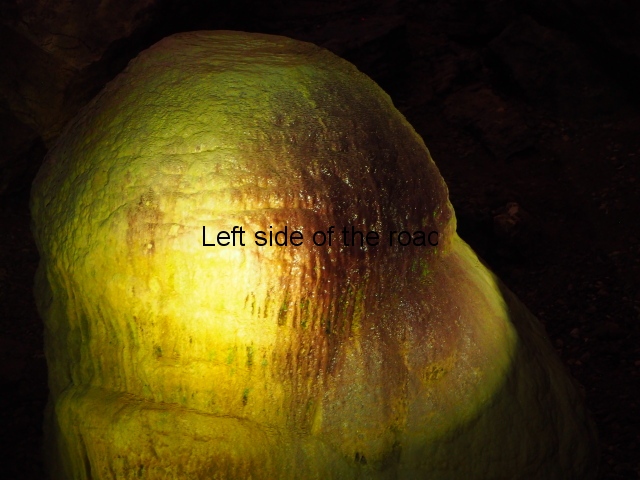

The Printing Press

The printing press

I wasn’t able to make out any manufacturers marks but I understand it is of a German make and was smuggled into the country in pieces. By all accounts it was state of the art machine at the time of its installation. Yet another expense that was ‘donated’ by the Tsarist state. By the beginning of the 20th century these presses could turn out thousands of copies relatively cheaply and from one plate.

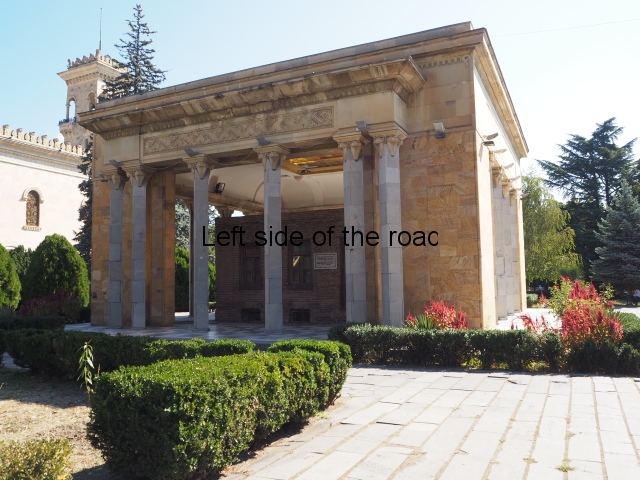

The house

The house

The house above would have been a relatively wealthy but basic house at the time. The living area is up a few steps and on to a veranda which leads to two reasonably sized rooms. Now they are quite dirty, unorganized and nothing like they would have been at the time they were the cover for illegal revolutionary activity.

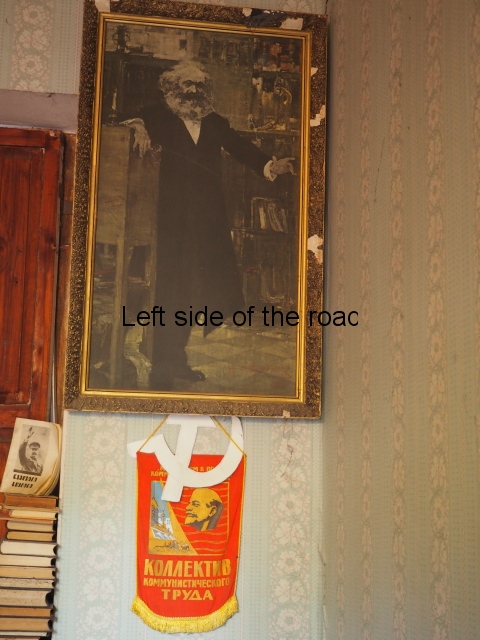

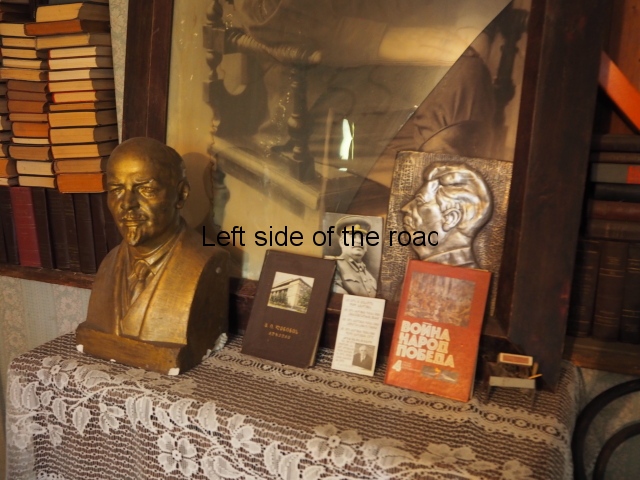

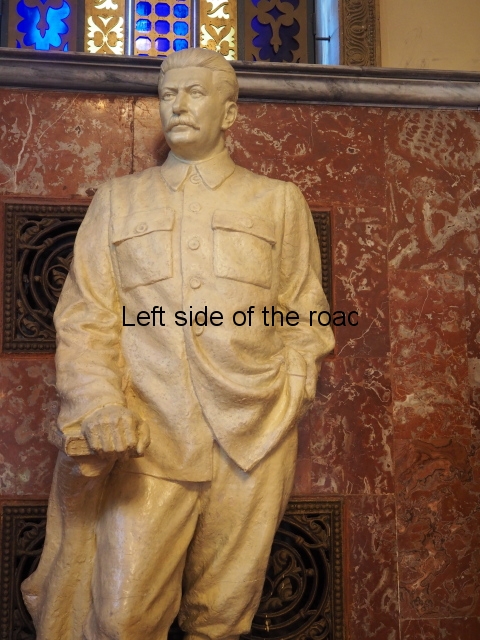

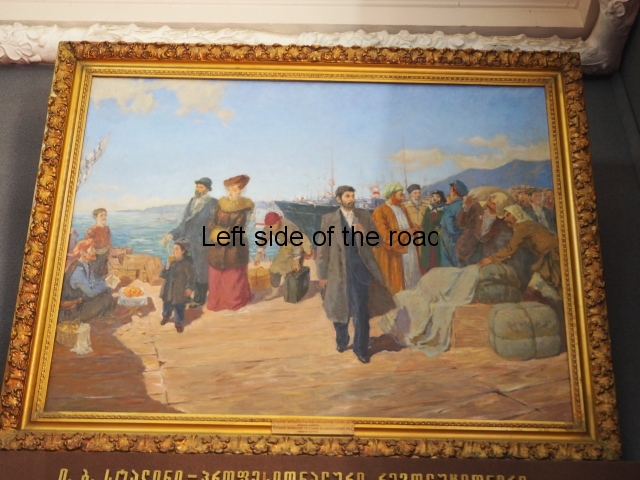

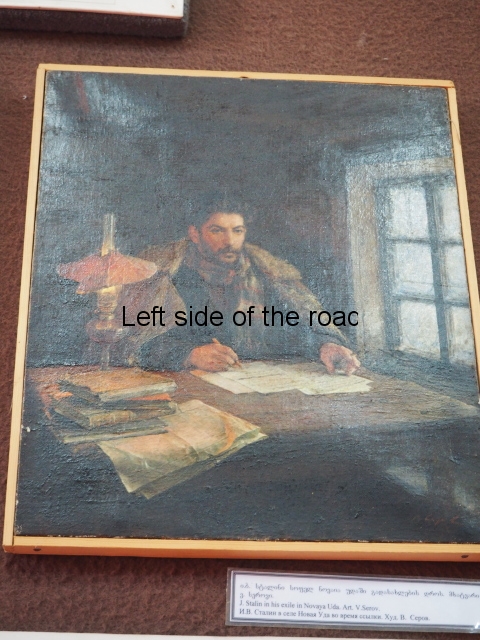

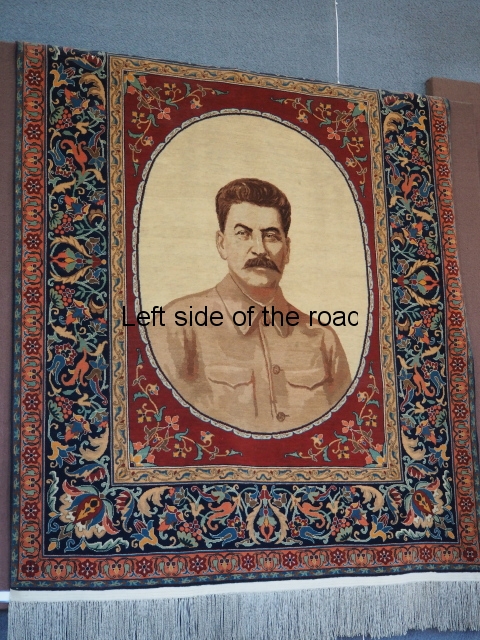

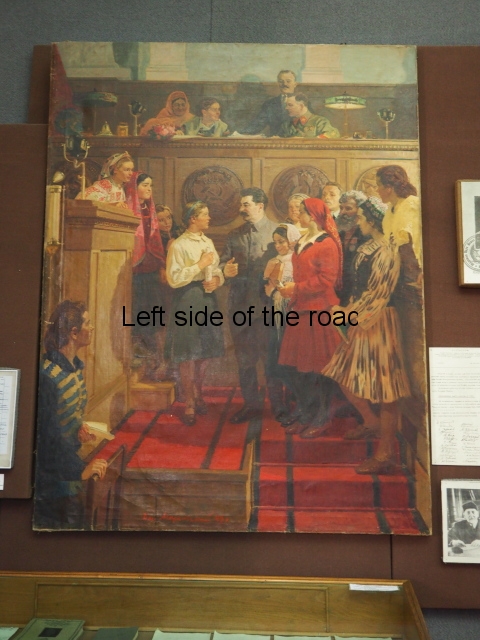

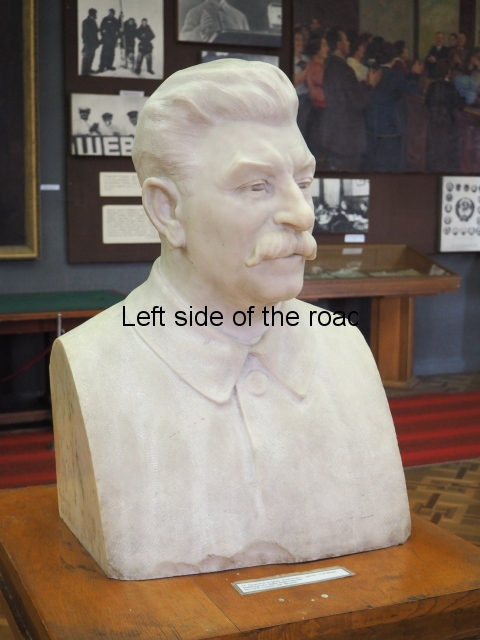

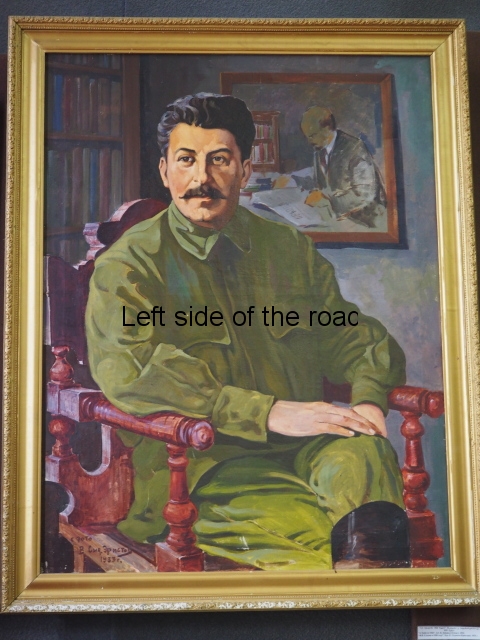

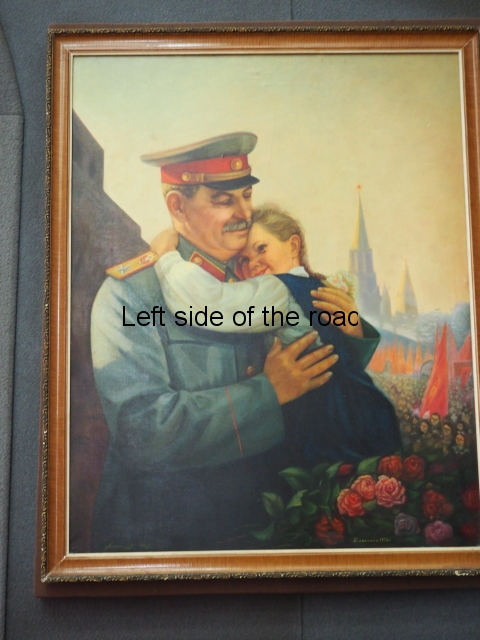

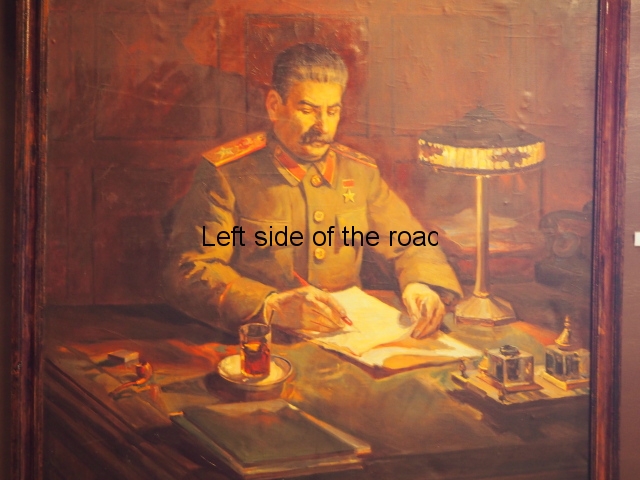

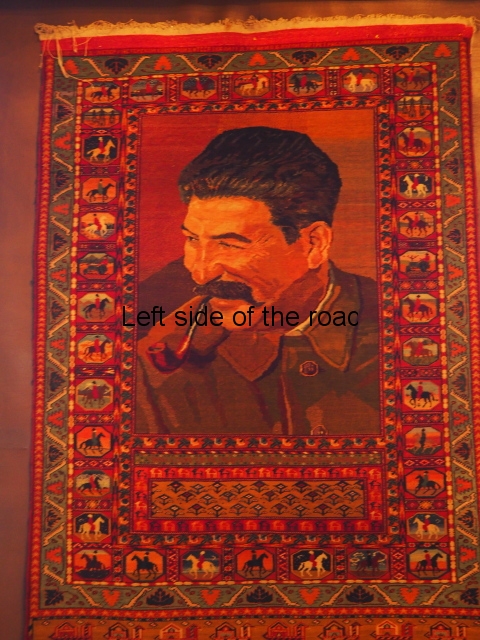

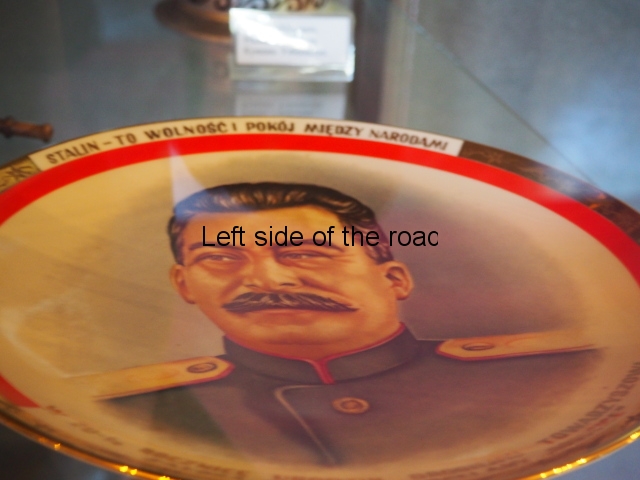

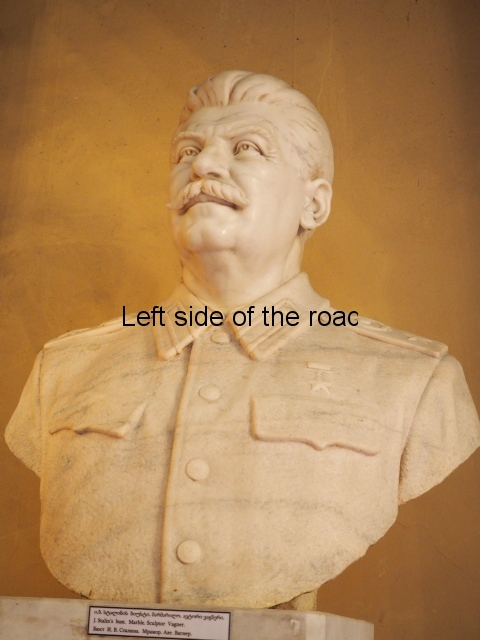

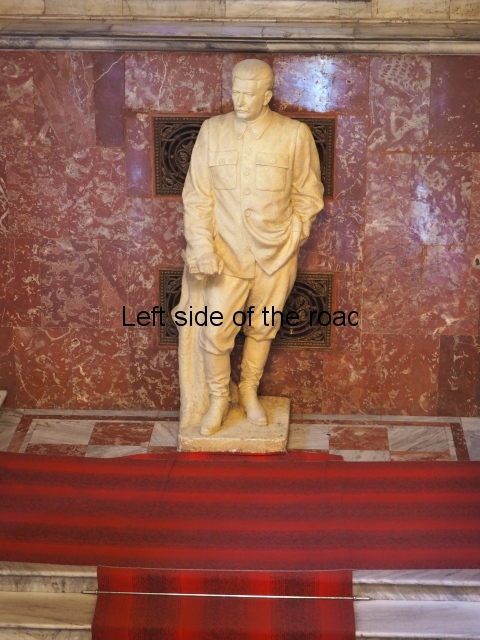

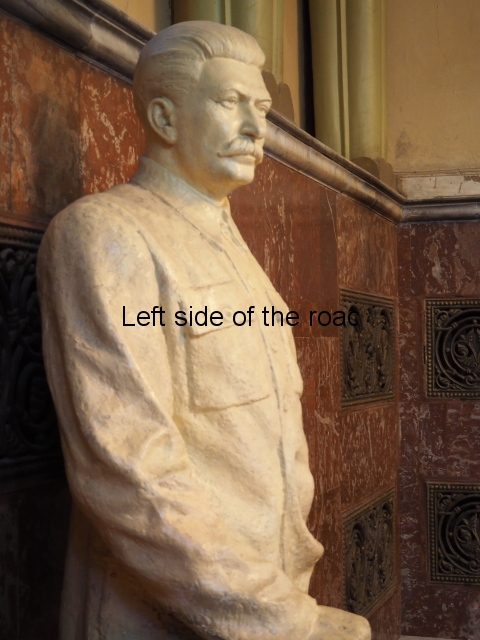

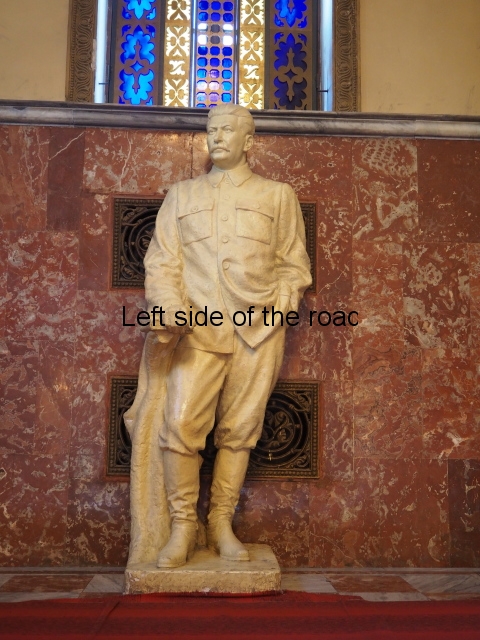

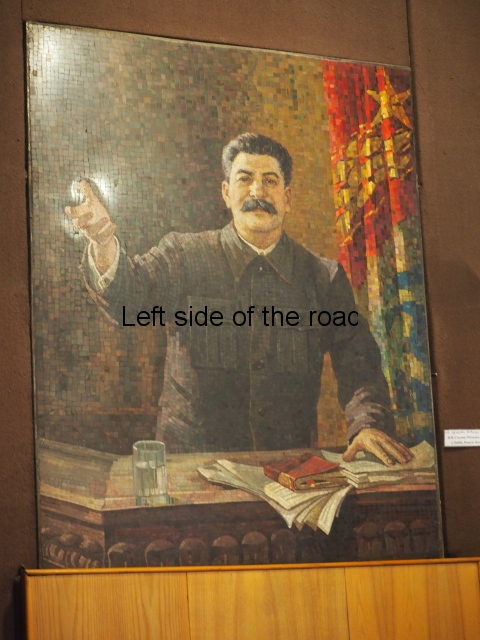

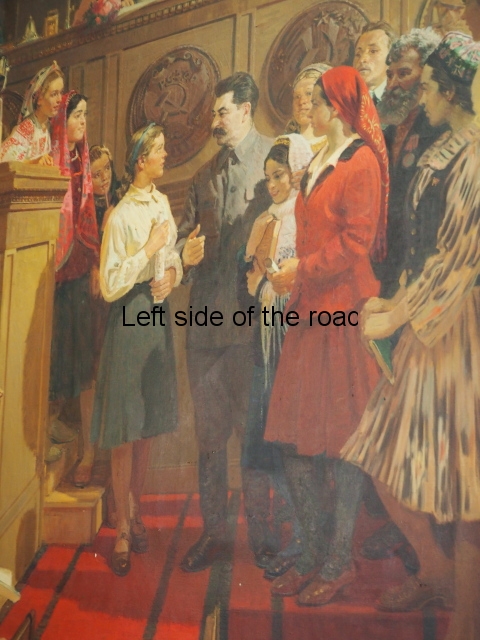

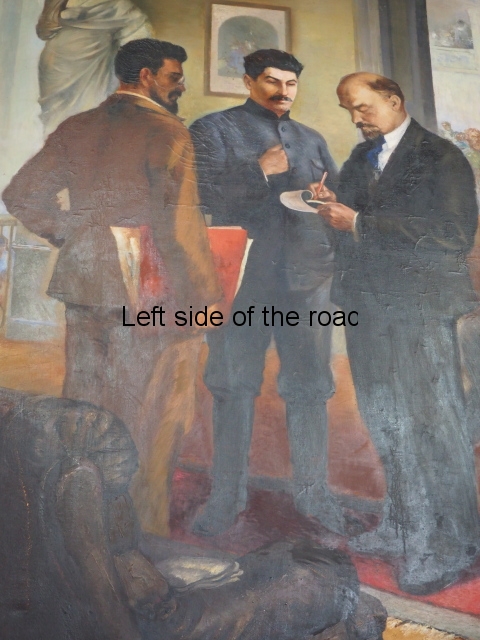

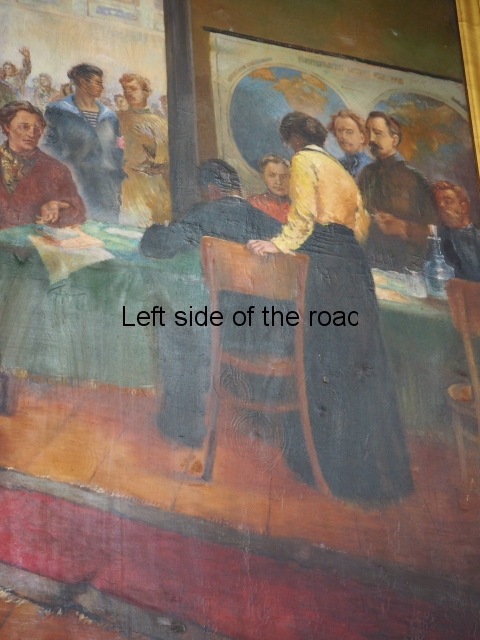

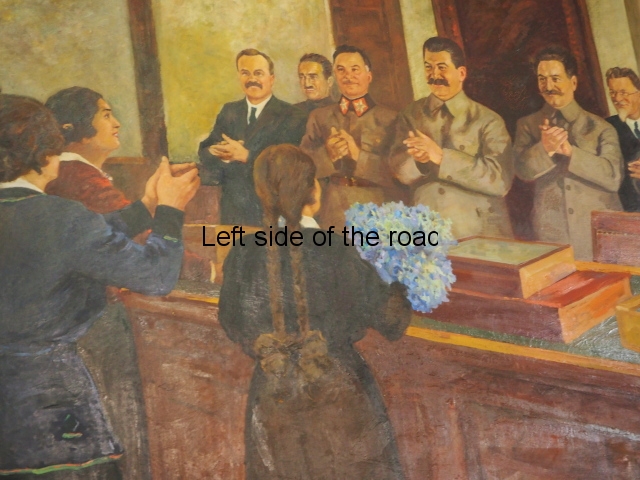

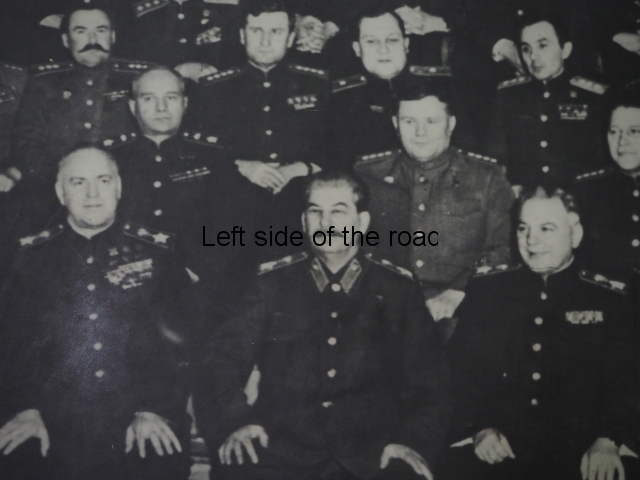

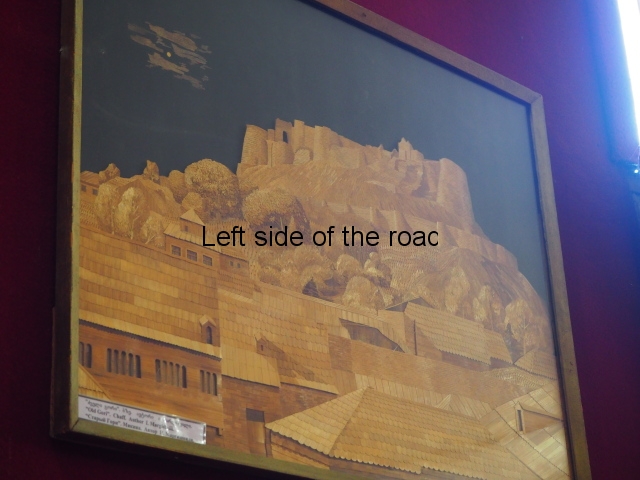

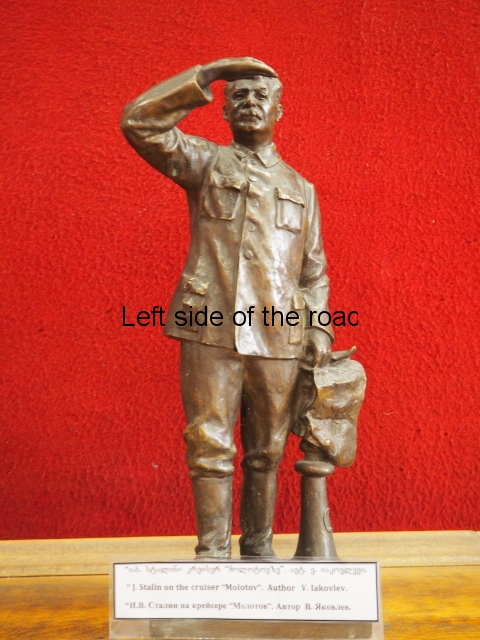

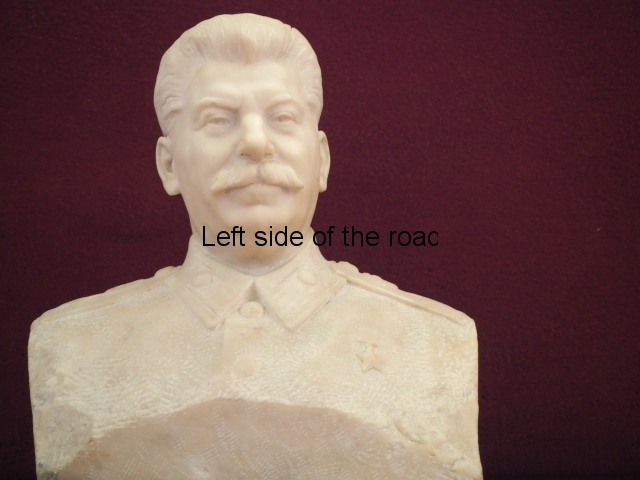

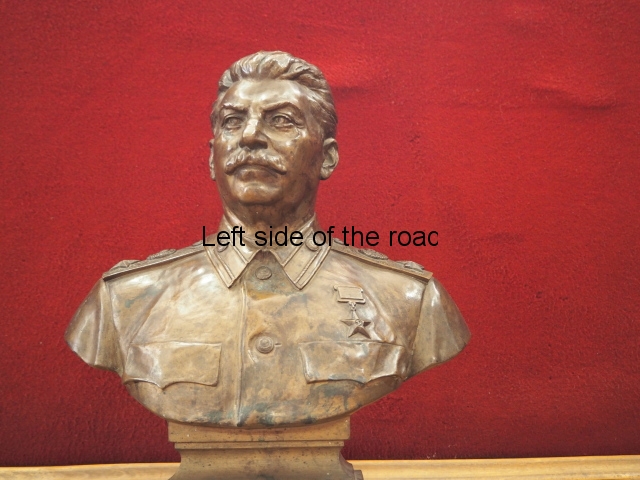

There are a number of pictures, plaques and the like of the revolutionary Marxist leaders, Marx, Lenin and Stalin as well as piled up books by those same leaders.

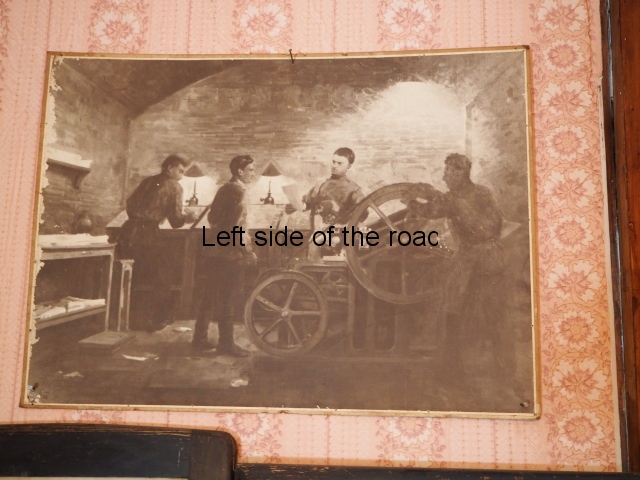

There’s also an interesting picture that gives the modern viewer an idea of how the underground room would have looked like when it was being used. No idea of when the picture was created but certainly long after the 1917 October Revolution and decades since the press printed in anger.

The press in operation

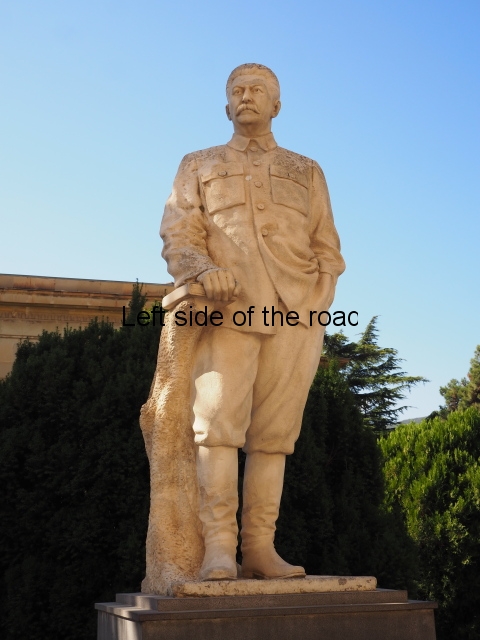

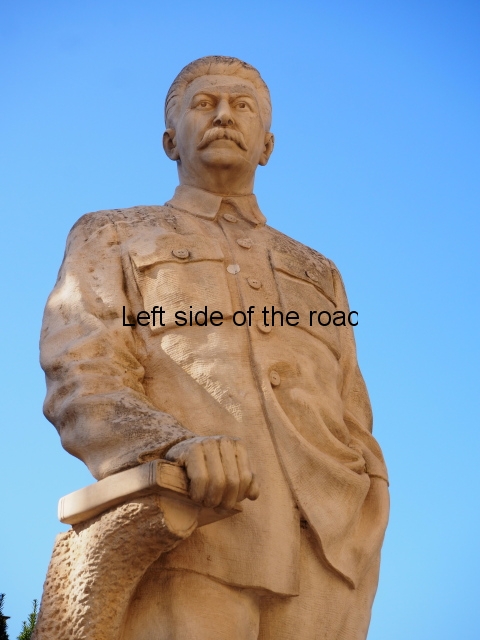

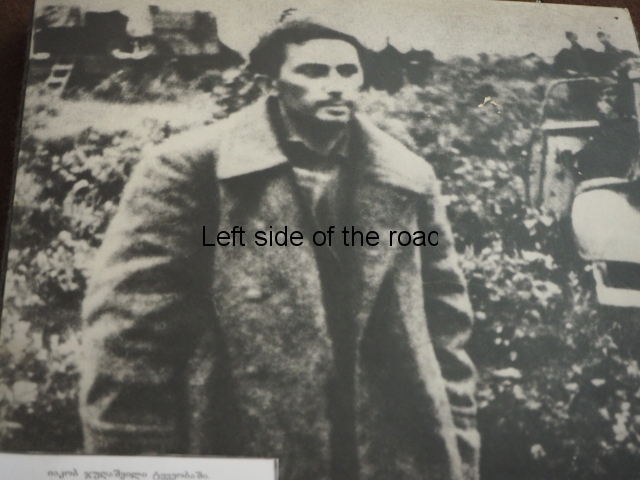

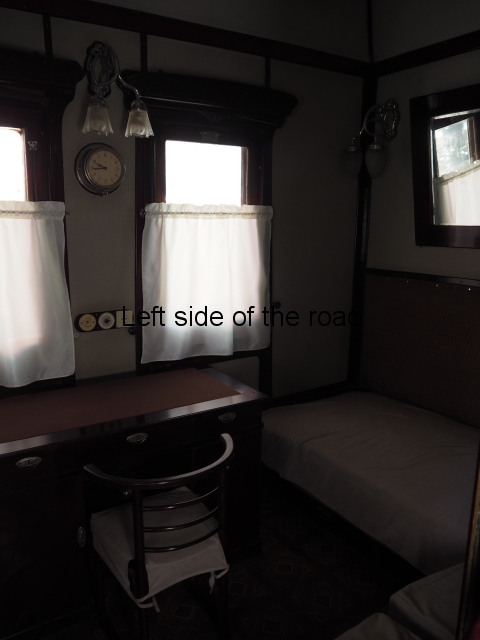

In the corner of one room (the one on the left) is an old, single bed – with a very lumpy mattress. Above this bed is a photo of Uncle Joe at about the age when the press was functioning. The guide will encourage you to have your picture taken, by him if you are alone, lying in ‘Stalin’s bed’. Here is another example of where tourism distorts history.

Any revolutionary who came to work on the press would not have stayed overnight in the house. That would have compromised security and put the whole of the project in jeopardy. And even though many of the leaflets and pamphlets would have been written by Uncle Joe he was not a printer and would have been in the way. Revolutionaries don’t always have to be able to carry out all tasks.

After April 1906

I haven’t been able to find out exactly why the press was abandoned in 1906. I can’t see that it was discovered by the Okhrana as I’m sure they would have destroyed the access shafts and tunnels – if not the whole of the building above. In the revolutionary movement there are always changes in trajectory, reaction becomes powerful for a period of time curtailing certain activities and then when circumstances become more favourable the revolution has moved on to other areas. The main focus of the Georgian Communists might have moved to other areas, for example Baku. Whatever the reason it wasn’t ever used again for its original purpose.

I’ve picked up a bit of information to indicate that it was opened as a museum in 1937 – probably at the time that Lavrenty Beria was in command of the Georgian Communist Party. That might have been when the present spiral metal staircase and new entrance to the underground room were created. Then the Great Patriotic War would have intervened.

Whatever might have been the fate of the building in subsequent years it now has no ‘legal’ status as a state museum and is showing serious signs of decay. The spiral staircase is a bit dodgy and the ladder that allowed access to the print room is rusting away in sympathy with the press itself.

Next to the house, on the right as the gates to the grounds are on the left, there’s a relatively modern, red brick building. This has a couple of ‘Hammer and Sickle’ images on the doors. This looks like it was, at some time in the past, a small museum to accompany the visit to the cellar. It looks derelict but I have no information if it is possible to enter. Having someone with Georgian/Russian language skills could possibly solve the problem.

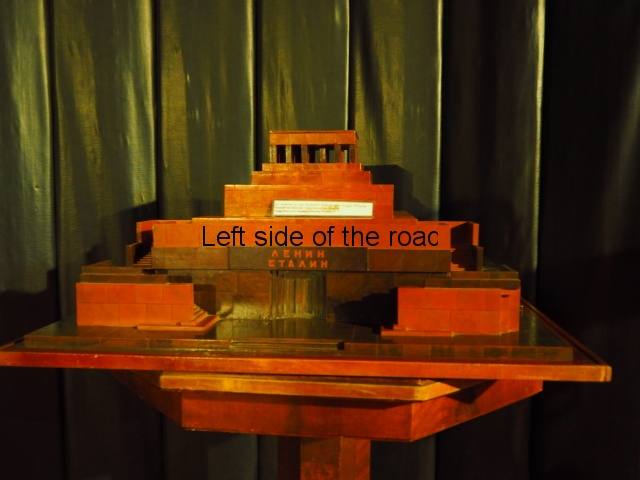

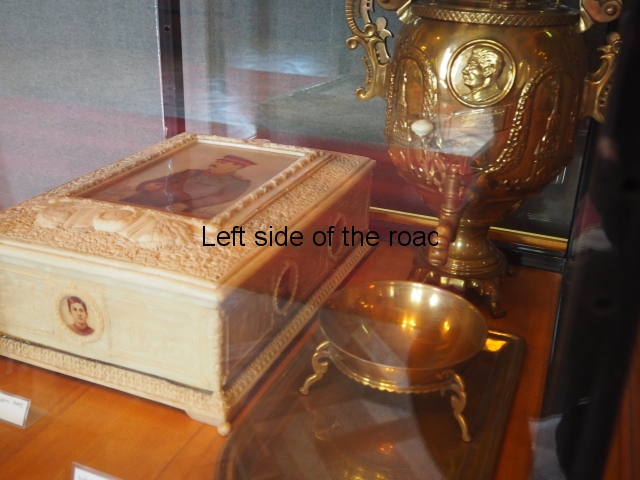

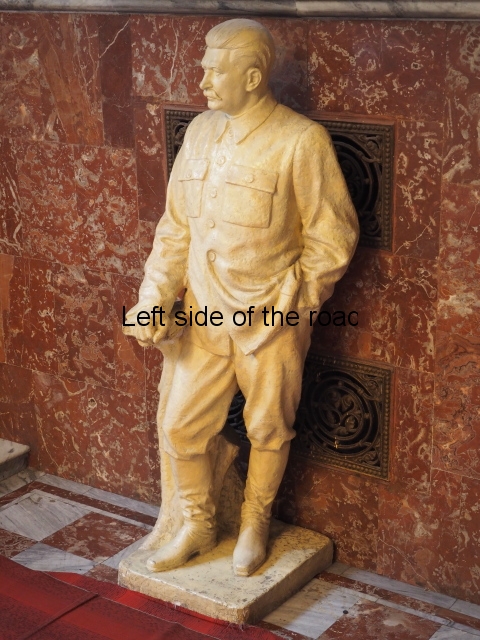

Stalin Museum

For those who have visited the Stalin Museum in Gori you might have noticed the maquette of the house and underground press in a glass case in Room No 1, close to the entrance to Room No 2. For those who are about to go there look out for it as it gives an interesting 3D impression of the site.

Visiting the Underground Press

There don’t seem to be any official opening times. The Guardian of the space seems to be there all the time during the day (and night). He doesn’t speak English but takes you to all the places and you can work out how matters stood over a hundred years ago.

There’s no entry charge as such but a tip of GEL10 seemed to be reasonably well received.

Location and how to get there by public transport

Arrive at 300 Argel Metro station. Leave the station and take the left, uphill. Take the second road right, towards the hospital, on Tsinandali Street (there’s a small bakery on the right, at the end of the street as you enter from the main road). Continue along this road, with the hospital on your left, to the end to arrive at a junction, going through two pillars of an entrance gate. Turn left, again uphill. This is Kaspi Street. Continue uphill, keeping to the left at another junction, and you will soon see a red brick building on the right. In the garden of the house with the press there are a couple of large plane trees. This is Kaspi Street 7.

GPS

N 41º 41.445′

E 44º 49.795′

More on the Republic of Georgia