Imereti

More on the Republic of Georgia

Tskaltubo’s abandoned Spas, Springs and Sanatoria

Introduction

For reasons that can only be guessed at you can’t look at a British newspaper, go to the BBC website or by looking for information about the Georgian town of Tskaltubo without coming cross articles, pictures or videos about the ruined health spa buildings (which were hugely popular in Soviet times and even after the so-called ‘collapse of Communism’) in the town.

It’s not that these buildings have been in the condition they are found today for a short period of time. They fell into disrepair when relations turned sour between Georgia and Russia over the provinces of South Ossetia and Abkhazia which led to open warfare in August 2008. The fighting war only lasted 5 days but the consequences have been around for much longer.

One of those consequences which has had a direct impact on the town of Tskaltubo was the use of the former spa resorts and hotels as homes for some of the thousands of refugees.

I don’t know exactly in what state these buildings, some of them huge and which had been the holiday home for hundreds in their heyday, were in the summer of 2008 but a refugee crisis that could have been handled with some sort of compassion seems to have been left totally to individual initiative and lacking any semblance of organisation.

By that I mean to imply that those who arrived first took what was useful to themselves and there was no communal approach to make the fullest – and most efficient – use of the structures of the former hotels.

Under the ideology of the Soviet Union (when it could still have been considered a Socialist state) the emphasis in such establishments would have been placed on the communal areas. This would have meant that the lower floors (including basements) would have been devoted to dining and concert rooms, general meeting areas and facilities for leisure activities (such as cinemas and theatres) and extensive kitchens to cater for so many people in a relatively short space of time.

It would have been on the upper floors where the bedrooms would have been found – but they were likely not all to have had en suite facilities (this was an invention even the likes of Britain took some time to adopt) and certainly no means of cooking.

Yet these were the spaces the refugees rushed to and which they then adapted to cater for the individualistic lifestyle they were attempting to establish. No doubt, in the process, any useful materials would have been looted from the communal areas below making them virtually useless at any time in the immediate future.

By all accounts there were many more refugees from the conflict in Tskaltubo than there are now but I visited at least seven of the old resort sanatoria which still had a substantial population in the autumn of 2019.

What dismayed me (but which the cretinous film crews and semi-professional photographers that have been swarming all over the place in recent times) was the very degradation and filth that characterises the communal areas. Some of this decay can be witnessed in the slide show a the end of this post. There could have been many more examples but I started to become both angry and depressed at recording such wanton vandalism and thoughtlessness that had made the living conditions of so many people so much worse.

I had the ‘opportunity’ of only visiting one person’s home – that of an old Abkhazian woman who tried to sell over-priced booze and cakes to any foreigner, like myself, who pointed a camera in the direction of the buildings. She was in the sanatorium I have called ‘It’s my business’ as I haven’t been able to discover its proper name and that was the phrase she used all the time during the few minutes I was in her ‘home’. I was given to believe that there are women like her in some of the other refugee occupied hotels.

It was truly sad to see how the fine entrance halls, staircases, dining and concert rooms – with decorated and vaulted ceilings – and the general communal areas had been allowed to arrive at such a state of filth and decay. Nothing that was considered communal was of consideration at all. This also meant there was no lighting in the entrances and stair wells meaning torches were a necessity once it got dark. Such a situation would do nothing in creating a feeling of safety and security

Wooden parquet flooring had been torn up, presumably to be burnt for cooking and/or heating. Anything of use on these lower floors – such as floorboards – had also been torn up leaving the surface below to degrade and in the process creating holes into the cellar. And the general lack of concern for an area that was ‘not their’s’ meant rubbish started to accumulate – and here I not just talking about historic rubbish but contemporary plastic drinks bottles. I suppose once the collective decision to live in shit has been accepted any more shit is neither here or there.

Broken water pipes and dangerous electrical wiring was everywhere and added to the build up of inflammable rubbish creating a haven for disease and vermin as well as storing up problems for the future.

The refugees from the 2008 war could have lived in relative luxury. They chose not to but to live in dirt and degradation.

But the Western European pricks with their expensive cameras and drones to provide an overall view of these once magnificent buildings don’t see anything other than an opportunity to demonstrate their cultural superiority.

But there’s also a political aspect of this highlighting of these sad ruins. Such a situation is always described with reference to the Soviet past implying that it was the Socialist system that was in some way responsible for the consequences of the present.

It is conveniently forgotten that even the Revisionist Soviet Union ceased to exist 30 years ago (and it hadn’t been a socialist country for more than 40 years before that), that in the years since the so-called ‘fall of Communism’ the ‘superior’ economic system of capitalism has singularly failed (as it could but not do) to resolve the ‘problems’ that existed under Socialism.

Even though the present Russian leadership and all its robbing hangers-on would have ended their days in a Siberian gulag at the time of Socialism they are considered to be tainted with the ‘evil’ of Communism. Any attack on Russia (as indeed is any attack on the now capitalist China – witness the way matters are being twisted over the management of the present (2020) coronavirus crisis when if it had broken out in the capitalist west free market economic forces would have prevented any effective measures to contain the outbreak – can anyone believe that any British government would put London in lock down?) has nothing to do with what policies they are pursuing at the present time but a propaganda effort to make sure that they get punished for being the first country that had the effrontery to challenge the capitalist system and establish a workers and peasants socialist republic.

And the targets for this denigration of any idea of establishing revolutionary socialism are the very people whose only long term guarantee of freedom from exploitation and oppression is the making of such a revolution – that is the workers and peasants of the world.

At the same time it has to be recognised that there are some very strange examples of how those people who had been brought up in a socialist system react to the environment around them when those systems (for various reasons) have collapsed.

Present day Albania is a prime example where the people seemed to have accepted the destruction of the very economic basis of their country for nothing in return. There’s a definable correlation between the vast migration of Albanians from their country to elsewhere in the world to the existence of an almost limitless number of abandoned and looted factories in the country. Added to that the division of the land into small plots virtually killed off a national agriculture.

But it isn’t just in the post-Communist countries that we see people destroying the vestiges of a past social system and reverting to a more basic economy. When the Roman Empire retreated from Britain in the 4th century the remaining Britons were incapable of taking any lessons from the invaders and reverted to a life style similar to what they had followed more than 400 years before. Lessons in hygiene and sanitation which the Romans had developed (of course only for a few) were forgotten and diseases related to such poor or non-existent sanitation were to kill millions in the subsequent centuries – cholera doing its worse well into the 19th century in Europe.

A look at some of the buildings, both those being now used as refugee accommodation and those that were visiting Soviet workers would visit to take ‘advantage’ of the curing radon infused waters and mud.

Sanatorium Aia

Aia

This is one of the newer buildings that make up the whole complex of Tskaltubo, i.e., constructed in the 1960s or 70s when demand for places at the spa town continued to rise.

As is the case in all the buildings the gardens and approaches immediately surrounding Aia hasn’t been cared for in years. The ground floor which housed the communal areas and dining rooms had been stripped of anything decorative and all you are left with is the bare concrete floors. Where it was coming from I don’t know but there was a lot of standing water. This water would have come from inside the building suggesting that the pipes (fresh water or sewage) are not in the condition they should be. I would also have thought a breeding ground for mosquitoes in the summer.

Aia also demonstrates something which is common in all the buildings, some of the finest dating back to the 1940s (or earlier), and that is the efforts to grab more living and storage space from the limited amount available. Many of the balconies had been blocked in with various scraps of wood or metal thus grabbing a few more square metres for the inhabitants.

Aia is basically a shanty town in the air.

Another common addition was the satellite dishes. I haven’t seen a great deal of Georgian television but I would be surprised if they are served up anything more edifying than the mind-numbing generic productions that dominate most country’s TV output.

As I was walking around this building the woman who directed me to the decoration in the old dining room also suggested that I go to the first floor where there was a woman who would sell the chacha and cake. Each building, it seems, has one.

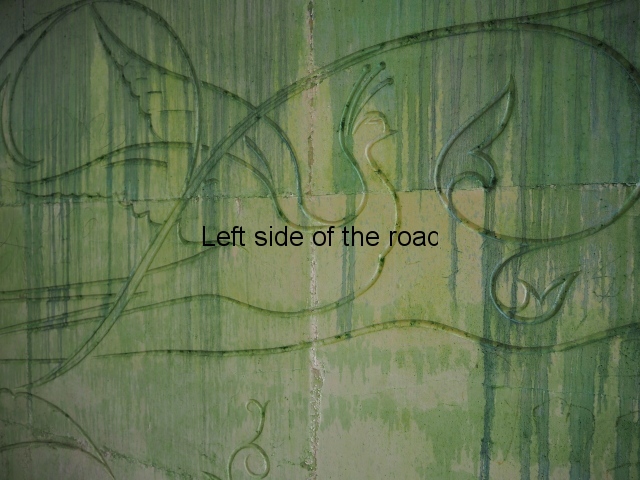

The Tile Mosaics

Aia – Grape Harvest

I don’t know why but I was expecting more internal decoration in the hotels than was the reality. Previous to my visit to Aia I seen the facade of Spring No. 6 – which has the bas relief depicting a visit of Joseph Stalin to the town. Many of the older buildings do have the lavish use of marble, parquet flooring, chandeliers and a general feeling of opulence but there was no real presence of the Socialist Realist art that I was expecting. Apart from at Aia – where there are two examples.

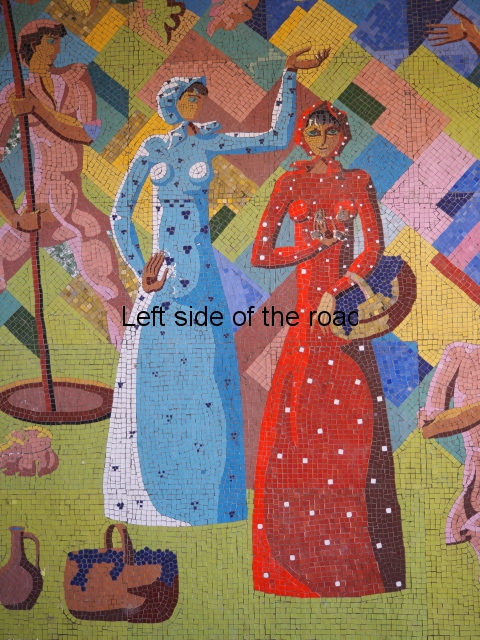

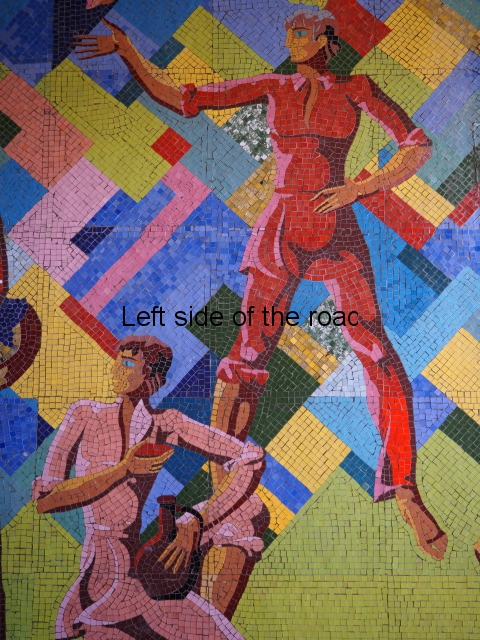

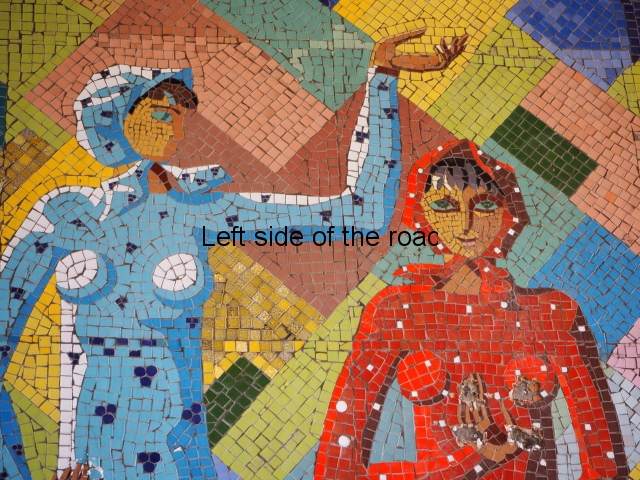

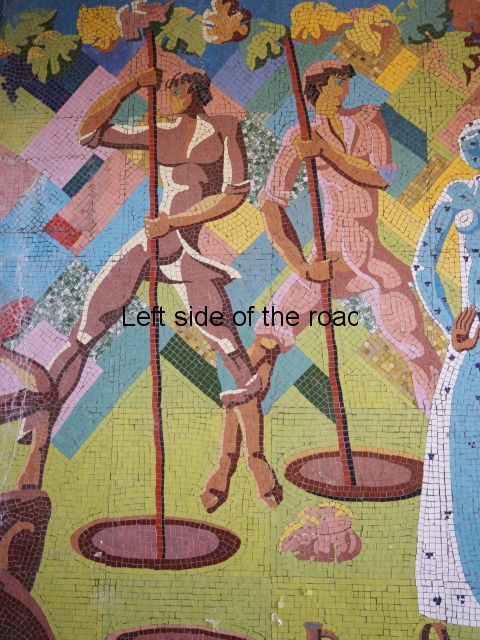

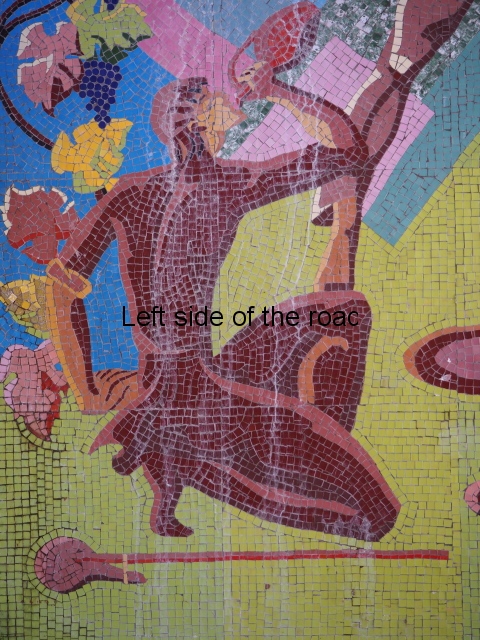

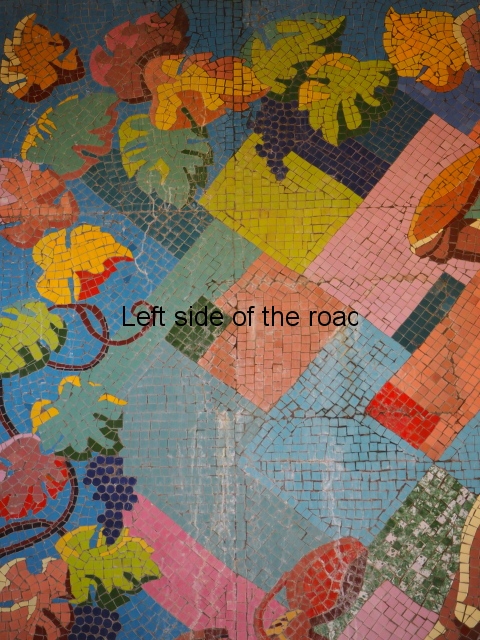

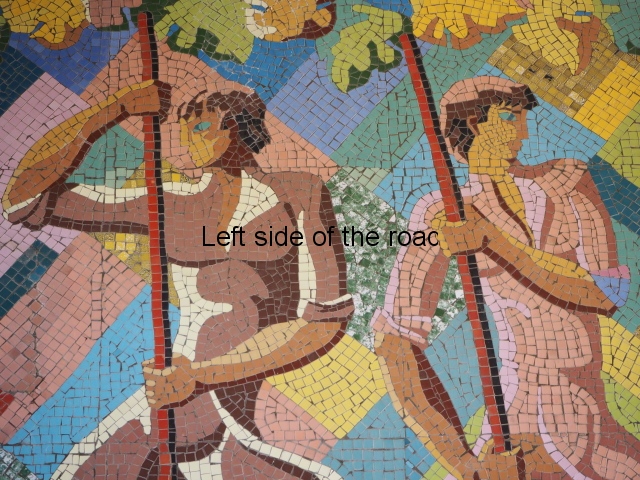

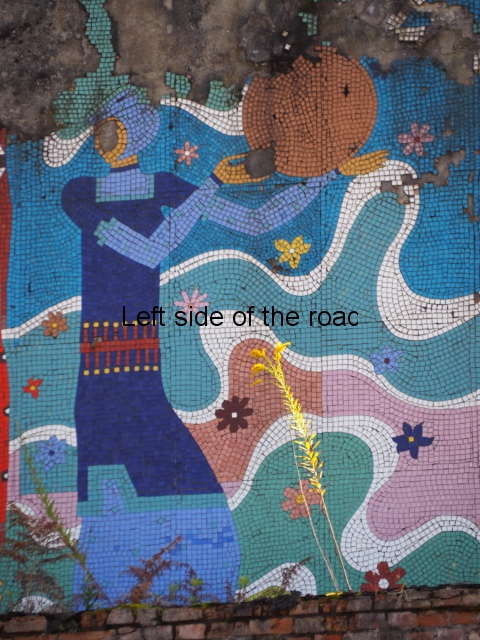

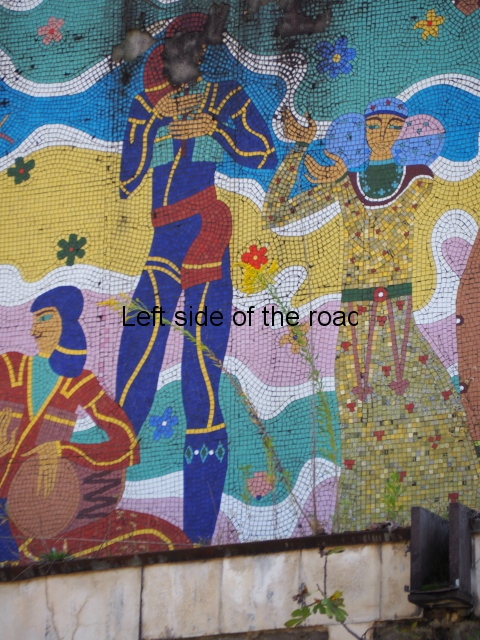

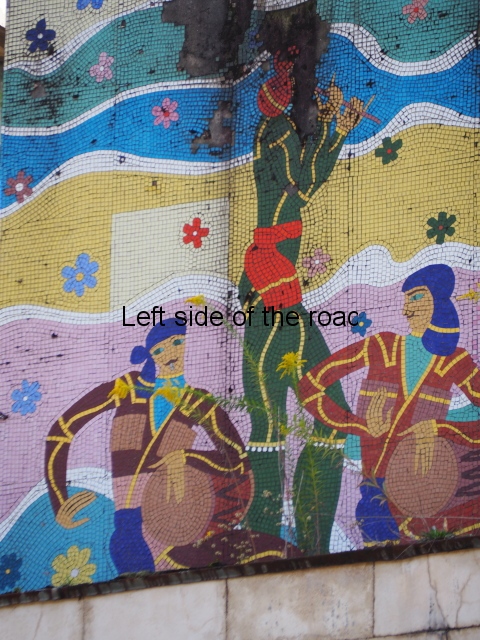

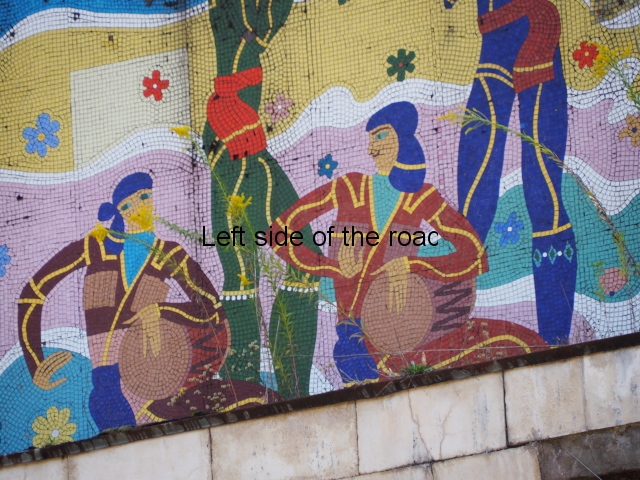

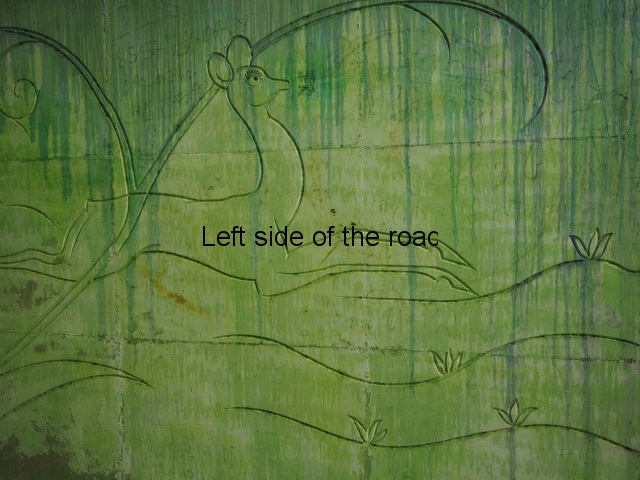

The first is in the area that would have been the dining room where one wall is covered with colourful tiles depicting the whole of the wine growing process. In the centre, and by far the largest characters, are two young Georgian woman reminiscent of the statue of Mother Georgia in the hills above Tbilisi. There is some damage, some of it which looks deliberate, but considering the circumstances in which the mosaic has to cope it is in a surprisingly good shape. There’s no protection from the elements, the damp conditions can’t help and it can get cold in Tskaltubo in the winter.

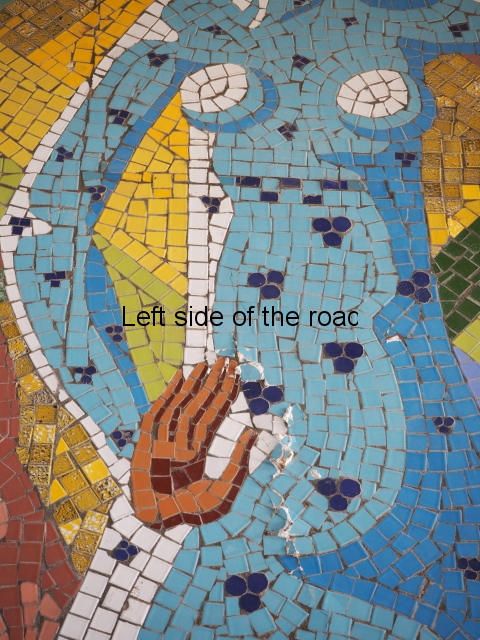

There’s another tile mosaic high up on the wall that would have looked down on the hotel’s garden. This depicts musicians and dancers in traditional Georgia dress. Unfortunately, this has not fared as well as the one in the dining room, many tiles have fallen away and it also shows signs of serious staining and water damage.

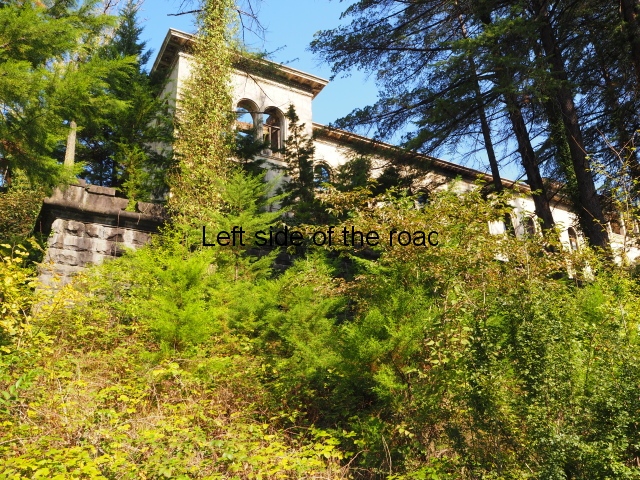

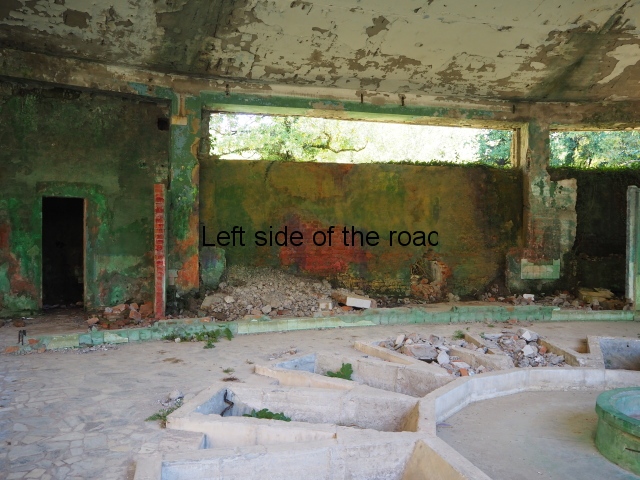

Sanatorium Imereti

Imereti

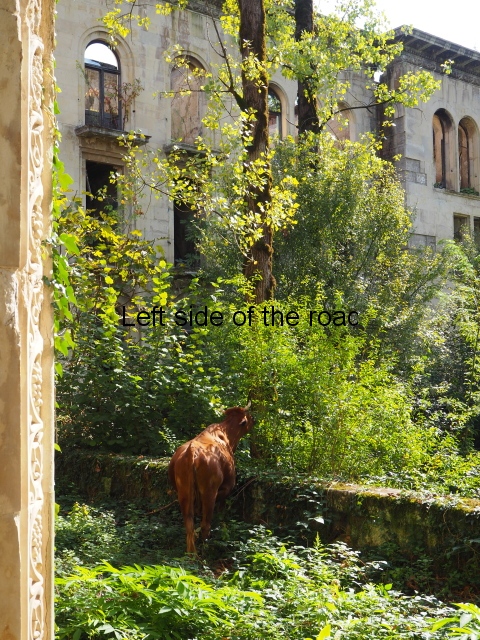

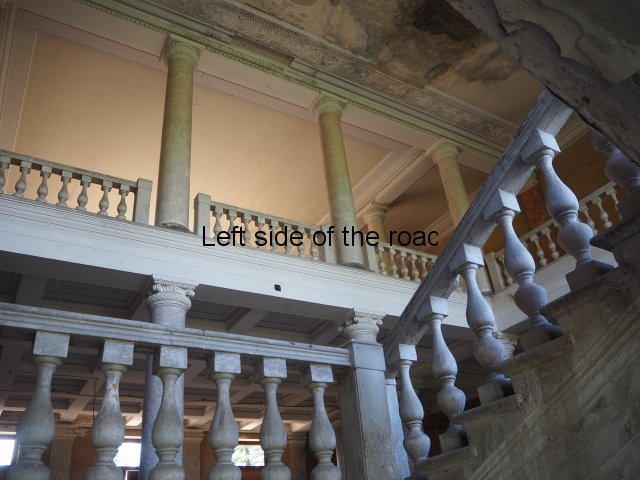

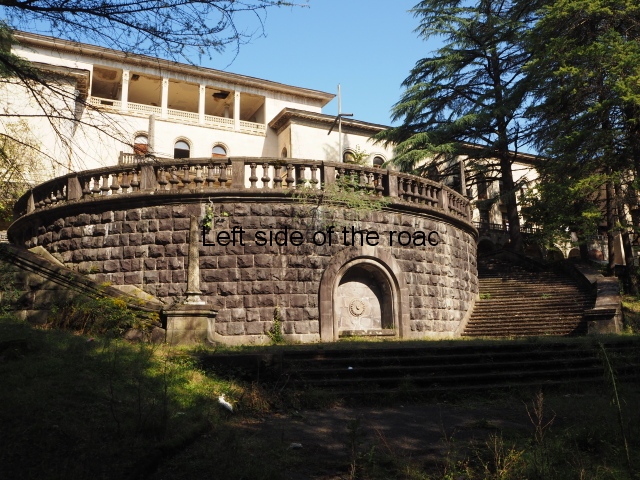

This was one of the grand creations of the early days of Tskaltubo as a spa resort. Built slightly up the hill from the main park which was the location of the bath houses Imereti is a neo-classical structure – not the utilitarian of the later Aia.

To approach the main entrance the visitor had to go up a sweeping, double set of steps to arrive at an imposing facade. Once in the building the entrance hall has marble classical columns which direct the visitor to a wide and high staircase that would lead to the bedroom floors.

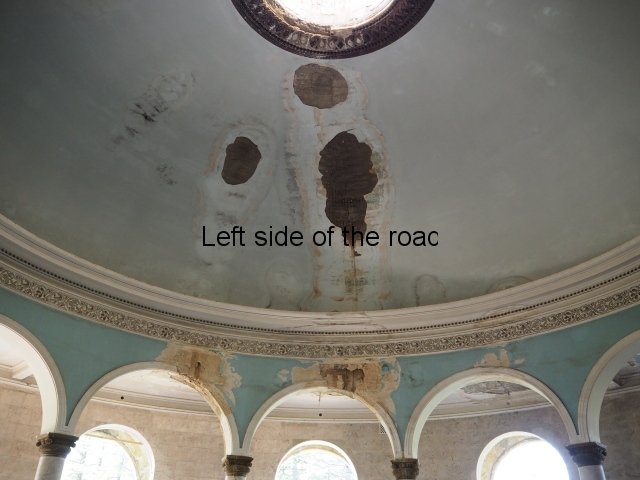

At one end there is a rotunda that housed a concert room with a vaulted ceiling and an internal circle of narrow columns, breaking up the space.

It would have been an impressive sight to a visiting Soviet worker. Now it’s a ruin in which no one should live – not even the cow that was feeding when I visited.

At the back of the building was a square where visitors would have congregated on warm summer evenings but now some of the space has been used as small vegetable gardens and the communal clothes washing area.

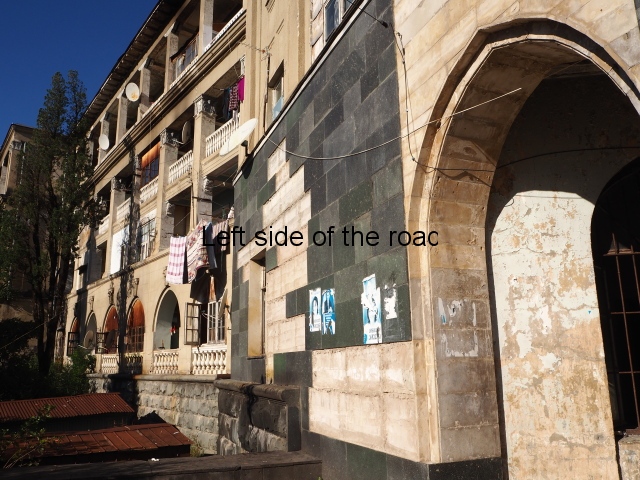

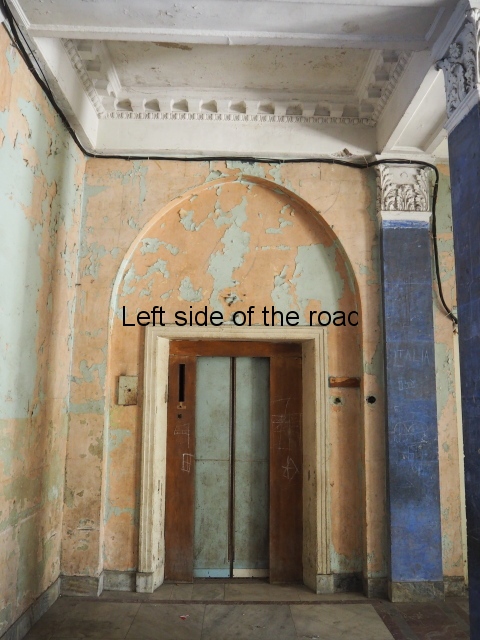

Sanatorium ‘It’s my business’

‘It’s my business’ Spa Hotel

Try as I might I haven’t (yet) discovered the true name of this building – hence the nickname based on the phrase used by the Abkhazian woman I met on my visit.

This is another of the really large and impressive early buildings. (Although I haven’t seen any dates for the construction of all the spa buildings a large commemorative urn that sits on a table in the main entrance to Spring No. 6 has pictures of many of the spas in Tskaltubo in full operation. The urn is dated 1961. The later Revisionist leaders of the Soviet Union went for utilitarianism rather than style.)

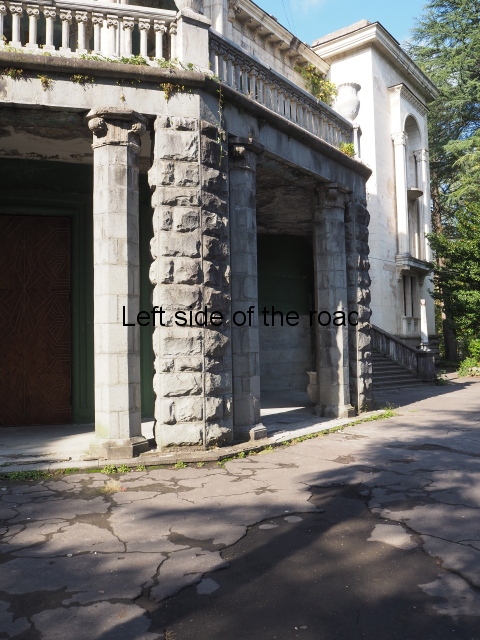

This takes its influence from early Italianate buildings, with large blocks of stone being used at the lower level and the square column topped towers that rise up on either side of the main entrance.

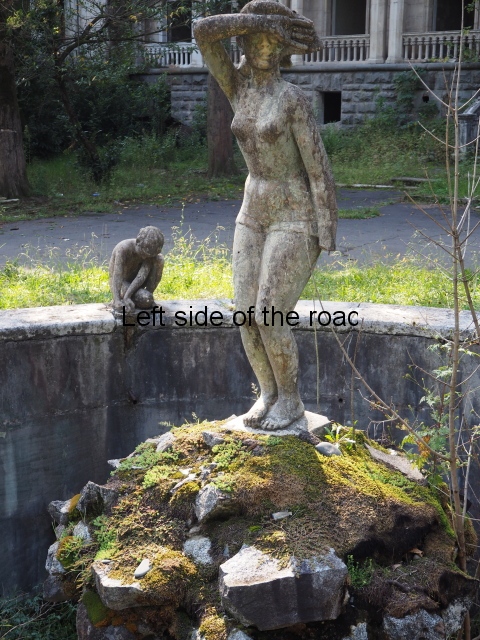

Apart from the ‘standard’ large communal rooms there are internal patios (with now derelict fountains) at the back together with roof gardens. Now all filthy with mould and overgrown with weeds.

It’s a long time since the lift in the main entrance was used and various side rooms are being used as plastic rubbish bins.

One interesting external decoration is the bas relief (I assume metal) high up on the east wall of the building, looking down on the terracotta mosaic of telephone workers.

Sanatorium Medea

Medea Sanatorium

This is one of the most impressive of the sanatorium which takes its architectural influence from the classical period. In a sense the area of the main entrance is purely decorative and serves little function. It’s more the impression the visitor got (and still gets – even though now in disrepair) when approaching the building.

The stone clad circular entrance has an external stair on either side which leads to a first floor colonnaded area. This is open on all sides and serves, really, no practical purpose. From here there is access to the main building but everything appears somewhat mundane after the initial reaction provided by the approach from the road. If this area does have any practical use it’s as a viewing platform of the area of the park and the hills around Tskaltubo.

As in some of the other hotels there are also patios and roof areas where visitors in the past would have enjoyed the summer warmth.

The not so interesting accommodation which is off to the left of the main decorative entrance is yet another that is being occupied by refugees. I can only imagine that the conditions on the lower floors are the same as in the places already mentioned. After a while it gets draining and depressing going into the different buildings to witness the same level of decay. It becomes even more depressing when you know that these are peoples’ homes and that some have been there for years and it seems an intrusion to constantly make a record of the squalor which surrounds them.

(I perhaps haven’t mentioned that there are a number of the old hotels which are completely empty of any refugees – or any other occupants with problems in finding a proper home – which are like blots on the landscape of the town. There is supposed to be an intention to develop some of these buildings but some are so huge and the clientele numbers will never reach anything like what was achieved during Soviet times that so many of these plans will remain pipe dreams.)

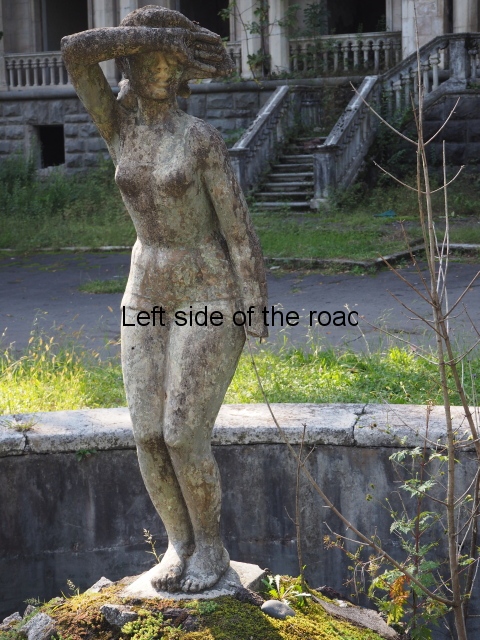

In front of Medea’s accommodation block there’s a small, circular fountain which is surprisingly deep considering there would have been many children in the area. Obviously this fountain is nothing more than a dirty, waterless hole now and the statues (of a young girl on an ‘island’ in the centre and four young, naked boys kneeling on the rim) are in reasonable, if not perfect, condition.

Sanatorium North-west

North-west Sanatorium

This is another building whose true name I have been unable to discover. It sits just outside the main park, in the north-west, beside the road that goes around the park. This one was, in fact, the first one I visited and it didn’t look that bad from a short distance, much of the building being shielded by the mature pine trees that separate the building from the road.

Once close up the same signs of decay mentioned before emerge. Like many of these hotels the entrances are impressive this one having a stone balustraded stairway on both sides of a small (now totally ruined) fountain, reached by a few flights of steps from the road.

The two storied building to the right of the entrance would have been the communal area and is a total ruin, to the extent that all the windows have been removed. On top there’s an open yet covered roof patio, again providing an outside area to enjoy the warmth of the sun.

Where there are people living they have followed the same practices as already mentioned. All of these buildings are architecturally unique but they have been reduced to the lowest common denominator by the addition of the makeshift additions and adaptations as well as the ubiquitous satellite dishes.

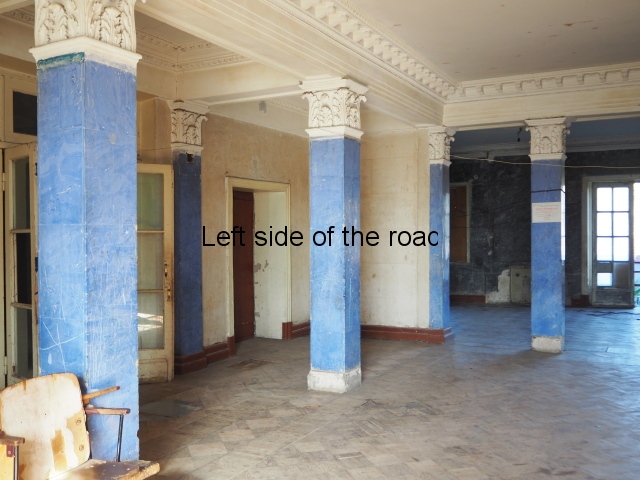

Sanatorium Iveria

Sanatorium Iveria

This is the sanatorium which is located furthest from the main park and the area of the baths but in many ways is one of the most attractive. There are not that many pictures of this building in the slide show as after I had squeezed my way through the corrugated sheets supposedly preventing access I didn’t have much enthusiasm to explore more.

I assume that this building would have been used to house refugees in the past but there is no one living there now. Added to that all the doors and windows have been removed so this might have been a tactic used by the local/national authorities to prevent the re-colonisation of these buildings when the previous inhabitants had either been rehoused somewhere more appropriate of had found an alternative themselves.

Unique in its design it has hexagonal stairwells at various points along the facade which are surmounted by small columned, hexagonal towers. The main entrance door is very distinctive in that it is under a very tall columned loggia, which extends two floors in height.

The ground floor entrance and the beginning of the main staircase is also in a better condition than many, much of the blue paint of the walls remaining as well as the plaster work on the ceiling being in a good condition. Probably why it has appeared in most articles about these sad buildings.

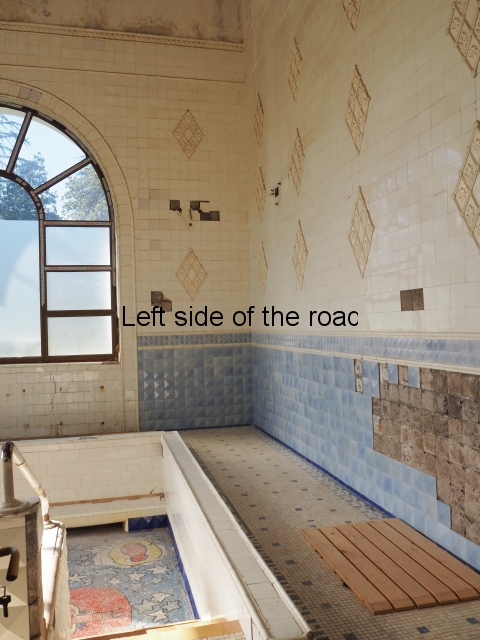

Spas, Springs and Baths

As well as the hotels a number of the spas, that are predominantly located in the central park, have also fallen into disrepair. These are in a different category to the hotels and resorts that were used to house refugees after the Russian-Georgian conflict. Tensions between the two countries increased, the spas and bath-houses that were built to cater to thousands were receiving fewer and fewer visits and after the war there was no where for them to stay.

Present day visitors can still take the water (and mud) treatments in Springs No. 1, No 3 and No 6. Numbers 1 and 3 are relatively modest buildings where Spring No. 6 is a much larger and grander structure. It is also the Spa that contains the extremely luxurious spa that Stalin used on his visits to the town.

Spring No. 4

Spring No. 4

There’s not a great deal that can be said about Spring No 4. It’s a one level, square building, probably built in the 1950s but today (of all the buildings from the glory days of the Soviet Union) it is the most difficult to enter and it is protected by substantial locked gates. Whether it is hiding some particular gem I have yet to discover. It can be found at the northern end of the park, close to the Palace of Sport.

Spring No. 5

Spring No. 5

Spring No. 5 is a little bit more decorative that No. 4 – probably indicating it was built some years earlier.

As I type this I start to think that probably the change in the architectural styles indicate the the simpler, concrete structures, of both the hotels and the spas, were part of Khrushchev’s attack on the Socialist developments that were achieved under the leadership of Joseph Stalin. The magnificent Metro stations that were in major cities such as Moscow and Leningrad also started to become more mundane and ‘normal’. This change in approach started very soon after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (of 1956) where Khrushchev – in a secret speech – denounced the great Marxist-Leninist leader of the party and implicitly all that had been achieved in the years since 1917.

The words Khrushchev and culture didn’t, and still don’t, really belong in the same sentence. He had no concept that what was produced for the workers and peasants should have been as good, well constructed and attractive as – or even better – than that produced for the wealthy. But he was a mere manager and started the thinking in the Soviet Union that was to soon lead it to revert to being a bastion of capitalism – even when under the name of the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics.

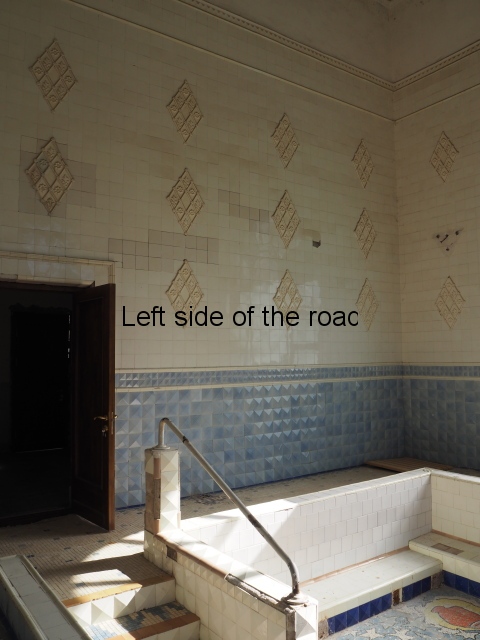

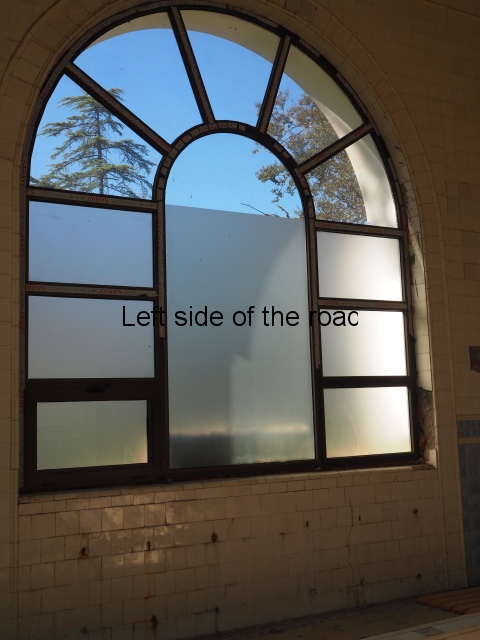

It’s the largest of the abandoned springs and is second only to number 6 in size. The impressive loggia over the front, principle entrance is its main attraction but the large, individual tile faced baths which shoot off from the main corridor indicate it was a centre for water treatment.

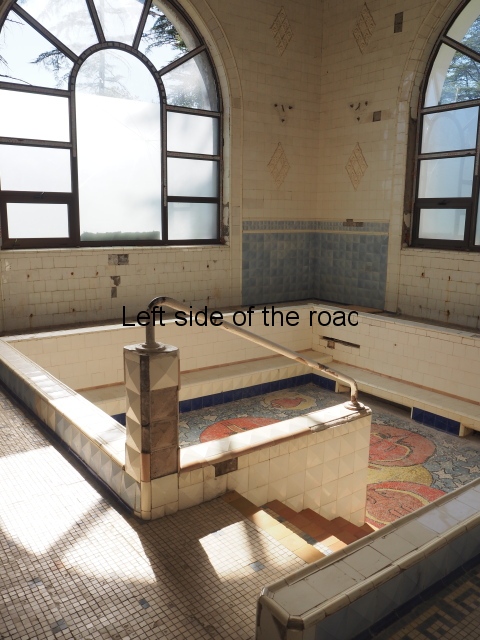

Spring No. 8

Spring No. 8

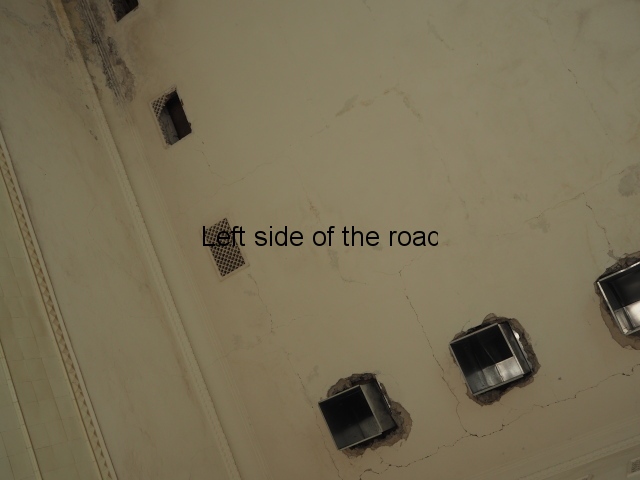

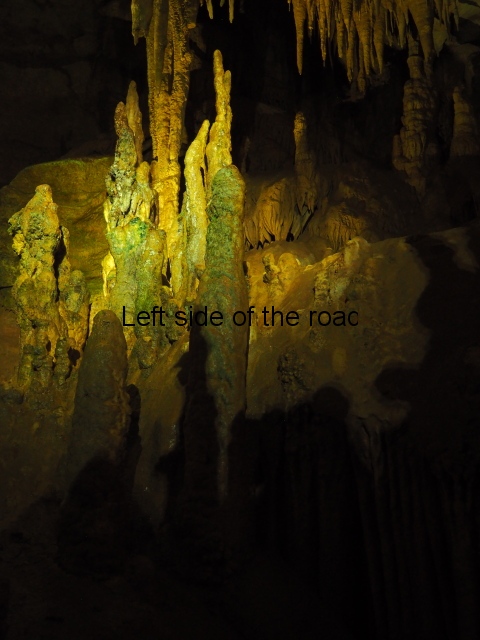

Spring No. 8 is another interesting construction. Probably from the late 1950s it’s a low, one level, circular building which doesn’t seem to have a special entrance. In the middle of the concrete ceiling there would have been a large glass dome (long gone), both bringing in natural light and the heat when the sun was shining.

The very layout and decoration of this building indicates to me that it was designed for children. They could play in the warm waters, supervised, whilst their parents might have been having treatment for whatever their medical ailment might have been.

Click on image to download a much larger pdf version

Key to Map

- 1 Sanatorium Iveria

- 2 Sanatorium Shakhtar

- 3 Sanatorium Imereti

- 4 Sanatorium ‘It’s my business’

- 5 Sanatorium Metallurgist

- 6 Sanatorium North- west

- 7 Spring No. 4

- 8 Spring No. 5

- 9 Sanatorium Savane

- 10 Spring No. 8

- 11 Sanatorium Medea

- 12 Sanatorium Aia

- 13 Sanatorium Sakartvelo

- A Spring No. 6 (and Stalin’s ‘private spa’)

More on the Republic of Georgia