National Art Gallery ‘Sculpture Park’ – Tirana

Each time I’ve been to Tirana I’ve made it a point to visit the impromptu ‘sculpture park’ that has been created behind the National Art Gallery, just down from the main Skanderbreu Square in the centre of Tirana.

The Art Gallery itself has only a very few actual sculptures on display inside the building, the emphasis being on paintings, especially those from the period from 1945 to 1990, where the dominant style was that of Socialist Realism.

But the area behind the gallery was constructed not for the display of works of art but as a service access to the building. And as the gallery is a public building this area shows the lack of care and investment in maintenance that is the general fate of public spaces in the whole of Albania, not just the capital of Tirana.

The statues that are now there would have previously held pride of place in some public square in different parts of Tirana but there is no indication of their provenance. Some have been damaged, either by accident or design, the statue of the great Marxist and first Soviet leader, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (the work of Kristina Hoshi, the original of which was created in 1954 in cement) in bronze, missing his right arm from the elbow. This once stood proud close to its present position, in the park across the road.

Many of the statues of individuals from the socialist era take on the pose of some famous meeting and the stance that Lenin takes in this statue can be seen on a number of photos from his relatively short time as leader of the first socialist state (his life no doubt being cut short as a consequence of an assassin’s attempt in 1918 which failed in its aim but which meant that a fragment of the bullet could not be removed from Lenin’s brain).

VI Lenin in Tirana – 1970

When it comes to the great Marxist leaders they are always (at least here in Albania) depicted with their right arm making some sort of gesture or greeting whilst slightly behind their bodies, in their left hand, they hold a roll of paper as if they are about to make an important proclamation.

Although this damage is unfortunate at least it allows an insight to the form of construction of these statues. They are not made of solid bronze, as many would think, but of a hollow bronze that’s only about a couple of centimetres thick. This relatively cheap construction technique explains why so many statues were erected in virtually every town in the country (it also explains why it was so easy to topple these statues in the counter-revolution).

Although few in number this small group provides quite a deep insight into the thinking of the Party of Labour of Albania during the 45 years it was the dominant political force within the country and attempting to construct a socialist society.

Uncle Joe – in happier times in Tirana

Socialist Albania gave women a role in society and assigned them an importance that has never been surpassed, either in the Soviet Union which proceeded the victory of Socialism in Albania or any other country that has attempted to construct socialism since. This is not the role of women in the higher echelons of society, the breaking of the so-called ‘glass ceiling’, the breaking of which only benefits a minuscule percentage of women in any society yet which gets most coverage in the capitalist media.

In Albania it was the women from the working class and peasantry whose lives were changed beyond recognition. In a patriarchal society where women were oppressed by virtual feudal social and economic conditions, as well as by the stultifying traditions of the church (of various trends) by the taking up of the gun during the war for national liberation against the Italian and German Fascist invaders they stated unequivocally that they would no longer ‘live in the old way’.

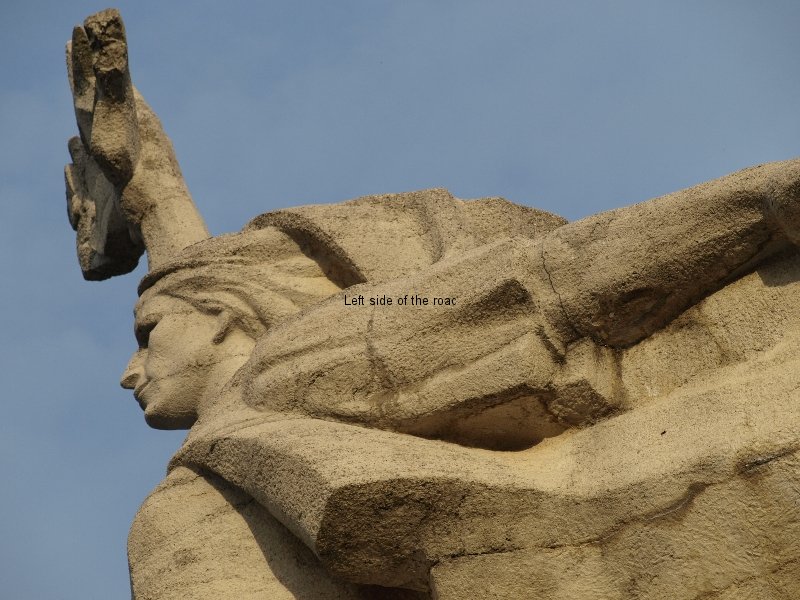

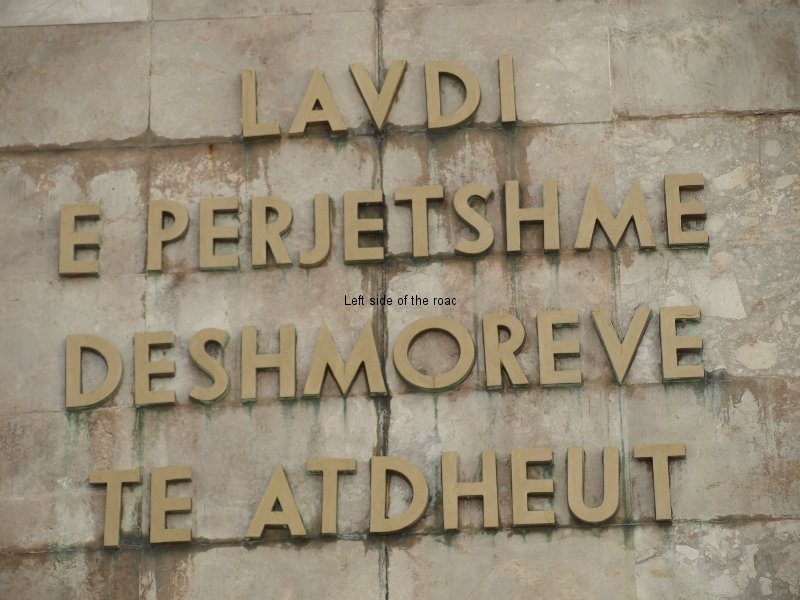

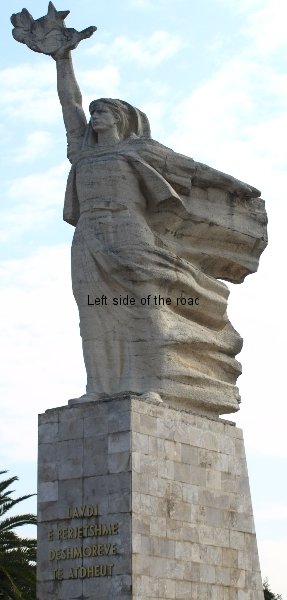

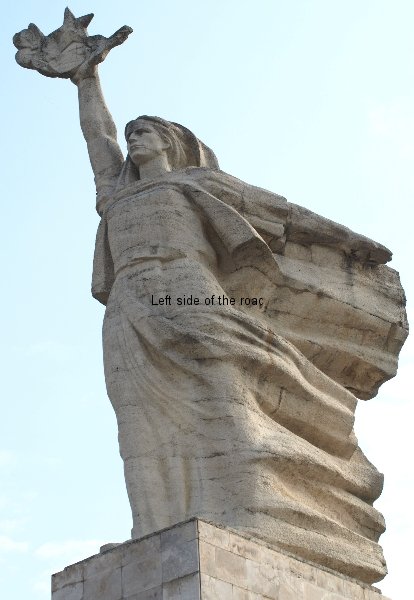

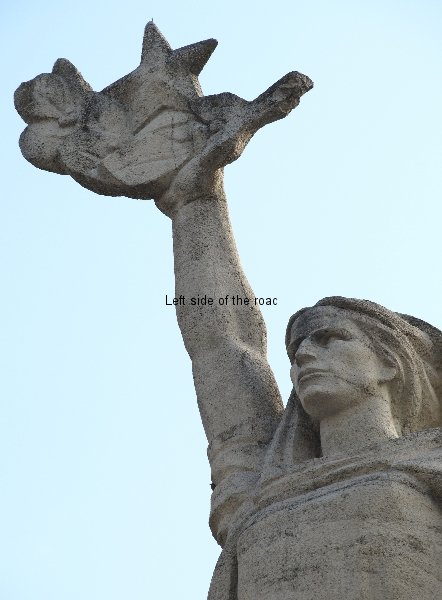

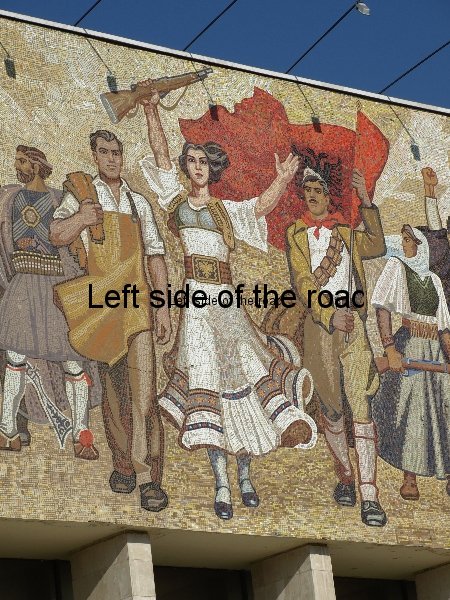

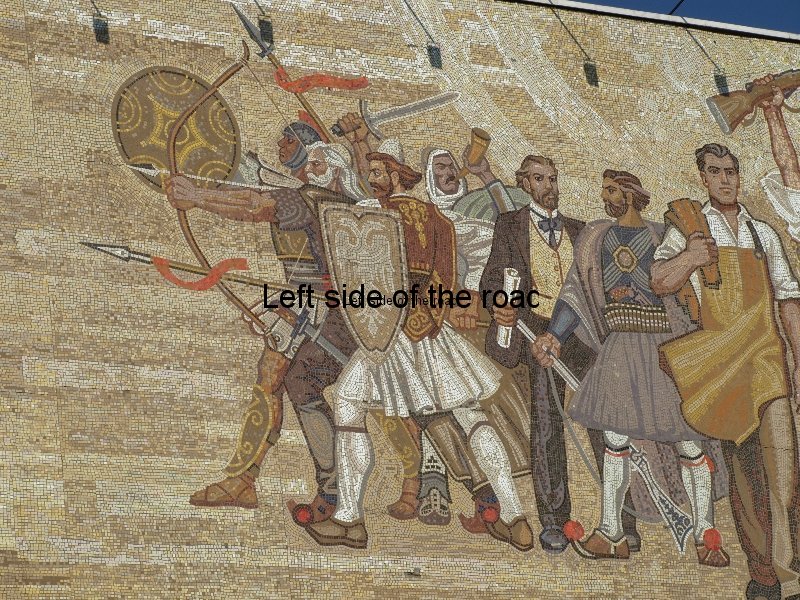

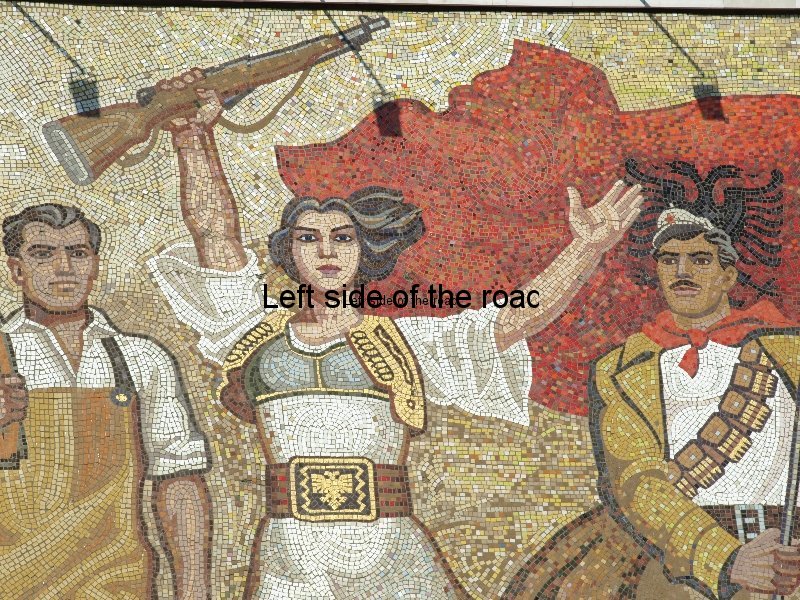

In many of the extent monuments to the struggles of the past a woman takes a central position and virtually always with a weapon in hand. Albanian women weren’t prepared to have ‘freedom’ given to them, they would fight for it themselves, freedom that would have real meaning. The clearest example of this idea can be seen in the huge mosaic on the façade of the National Historical Museum in Skanderbreu Square in the centre of Tirana.

The young woman depicted in the dirty shambles of the rear of the Art Gallery (in bronze) is of Liri Gero and exudes confidence in her own ability, looks the viewer straight in the eye (not looking down as ‘traditional’ society would have her do), has a gun strapped to her back and clutches a small bunch of flowers in her left hand. Communists fight for bread but for roses too!

The smallest of the collection depicts a male fighter (also in bronze) from one of the ethnic groups from the mountains of Albania demonstrating that the fight for freedom is not restricted to the ‘sophisticated’ city dwellers or a self-selected intellectual elite but should involve everyone from all sectors and strata of society.

Liberation Fighter

Another of the statues is a physical representation of one of the fundamentals of Albanian Socialist society, the Pickaxe and Rifle (Hector Dule, 1966, Bronze). Here we have a male holding a rifle, the butt resting on the ground, in his left hand whilst in his right he holds high a pickaxe. These two items are the equivalent of the Soviet Hammer and Sickle. Whereas in the Soviet Union the symbol represented the unity of the industrial worker and the peasant the Albanian Pickaxe and Rifle declares that the successful construction of a Socialist society depends upon physical labour protected by the determination of the population to defend any gains by force of arms.

Pick Axe and Rifle

The fact that far too many Albanians forgot this necessity during the counter-revolution of the early 1990s (and then seemed to lose all common sense in the chaotic years that followed, basically throwing out the baby with the bath water) doesn’t detract from the validity of this revolutionary concept.

JV Stalin – Skenderberg Square, Tirana

Finally we have the statues of JV Stalin and VI Lenin, the great Marxist Russian leaders so admired by the Albanian leader Enver Hoxha. I’ve already mentioned the damaged statue of Lenin. This statue, along with one of Uncle Joe, was covered by a tarpaulin just prior to the 100th anniversary of Albanian ‘independence’ in November 2012 – true independence for Albania (if only for 46 years) was achieved on November 29th, 1944. They have now been released from their dark penance but they have been joined by another new comrade who is, presently, covered with a white tarpaulin. I have been told this is a damaged bust of Enver Hoxha.

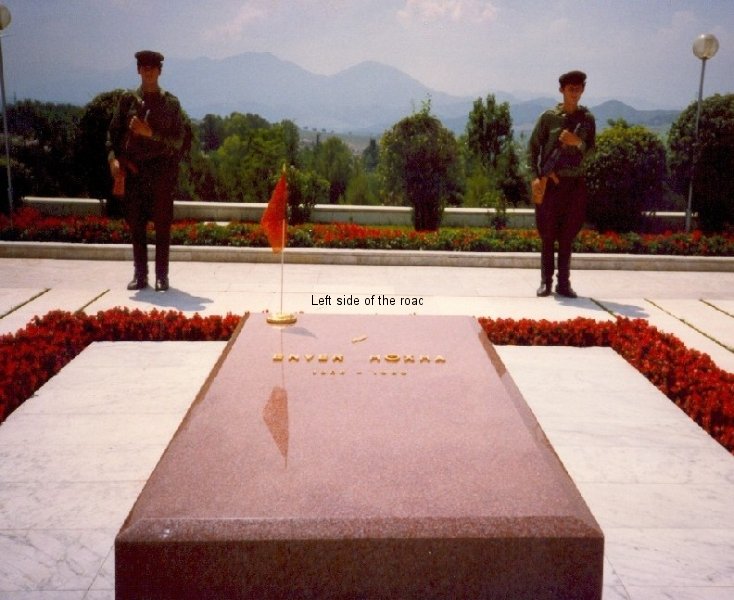

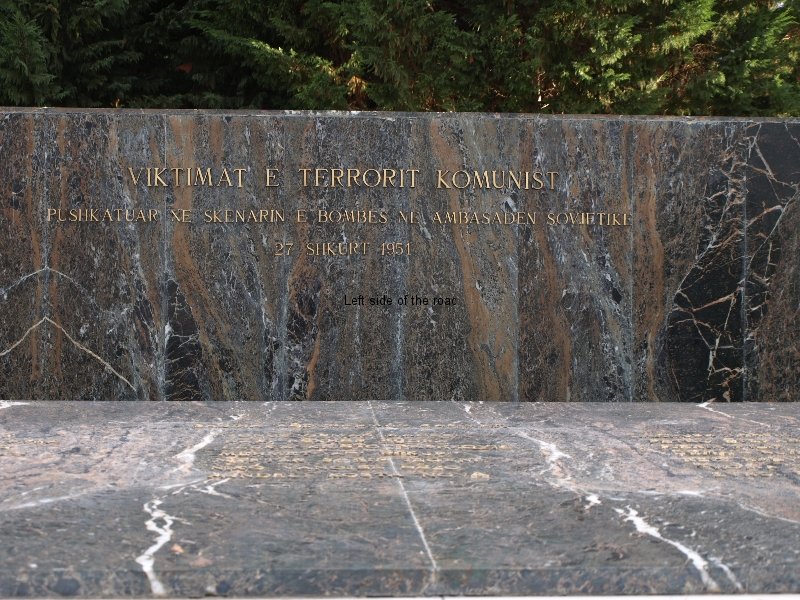

I was pleasantly surprised on my visit in October 2014 to find that there had been a new arrival to the small, select group. This was another, but somewhat larger, statue of Stalin. The ‘new’ arrival is in a less formal stance, without cap and is depicted as if greeting the viewer with his right arm stretched out. This is made out of bronze and as far as I can tell it used to stand in the square in front of the Bashkia (Town Hall) in the town of Kombinat – to the south-west of Tirana, on the old road to Durres.It’s at this point you would get off the bus if you wished to visit the grave of Enver Hoxha in its present location in the main city cemetery after being ousted from the National Martyrs’ Cemetery.

On one side of this square was the main entrance to the huge textile factory that gave the town its name (Kombinat means factory in Albanian). This has been derelict for many years and the ruins have slowly disappeared as the land has been cleared for other uses. The only noticeable remains of the factory is the main gate itself – with interesting decoration over the arches. You can get an ideas of how things used to look from a small painting called Voluntary work at the ‘Stalin’ textile factory by Abdurrahmin Buza and painted in 1948 which is on permanent exhibition in the Art Gallery itself.

It’s exactly the same as a statue that was placed in the oil and industrial town of Qender Stalin (now renamed Korcova, not that far from Berat) but there the statue was made from concrete and unlikely to have survived the chaos of the 1990s.

The original design was by Odhise Paskali whose other works number the statue of Skanderbreu on the horse in the square to which he gives his name in the centre of Tirana, as well as another of the national hero in the National Museum, this time not being a burden to a poor animal but standing on his own two feet. Paskali was also the artist for, among others; the group Shokët (Comrades) in Përmet Martyrs’ Cemetery; the standing Partisan on the monument to the Congress of Përmet in the town itself; a double bust of the Two Heroines of Gjirokaster; and a bust of Vojo Kushi, now in a small square on Rruga Dibres to the north of the city centre.

Perhaps one down side of a new Joe arriving is that the statue of the female Partisan, Liri Gero, has been moved to make way for the Man of Steel and is now facing the other statues, with her back to the Art Gallery. Is this yet another example of the return of a patriarchal society or is it, the reverse, that the female fighter is going to give a lesson to the men?

If I will ever be able to find out more details of these statues, i.e., who was the sculptor, where they originally stood, how they survived the counter-revolution and why they ended up in the shadows of the National Art Gallery remains to be seen.

One slight difficulty that has arisen since my last visit a couple of years ago is the presence of a ‘security’ guard who has to be circumvented in order to get a close view of the statues. Why he is so conscientious in this I don’t understand. If the authorities don’t want anyone to see them why place them out in the open? However, he can only be in one place at a time and when he is watching the world go by at the southern end of the gallery grounds, just creep towards the north.

NB From the end of 2021 the gallery has been closed. I have no information about exactly why but there had long been signs of the need for structural repairs. When it will reopen I have no idea. There didn’t seem to be much activity when I was in Tirana in the summer of 2022. Neither do I have any idea of what will be exhibited. There is, I’m sure, a possibility that the items that were part of the permanent exhibition, works of Socialist Realist Art, might well be confined to the depths and the gallery will become a centre of decadent capitalist ‘art’.