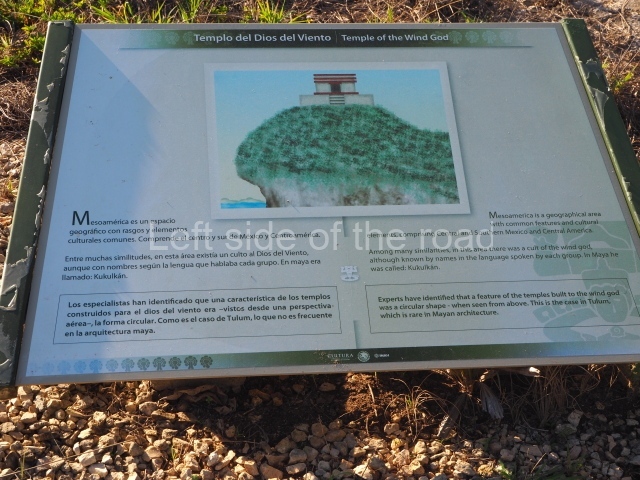

El Meco – Quintana Roo

Location

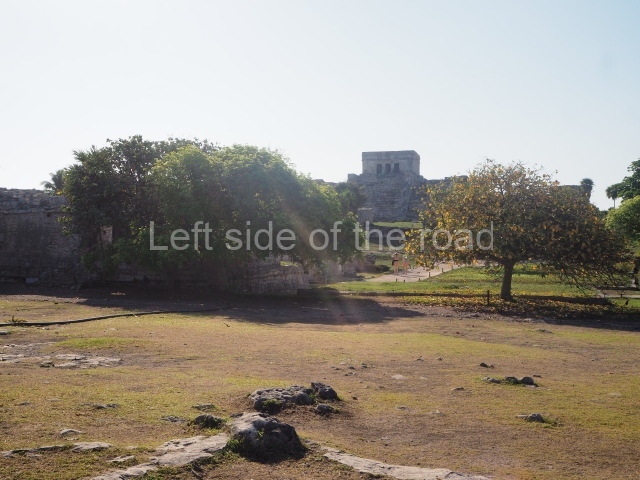

The pre-Hispanic settlement was built on a slight elevation 4 m above sea level, in an area of marshlands and mangroves. Although relatively small, El Meco is one of the largest settlements on the north coast of Quintana Roo. The site was split down the middle when the current road was built, with part of the residential area and a pre-Hispanic pier occupying the section closest to the sea. El Meco lies north of the city of Cancun, just 2.7 km away on the Puerto Juarez/Punta Sam road.

History of the explorations

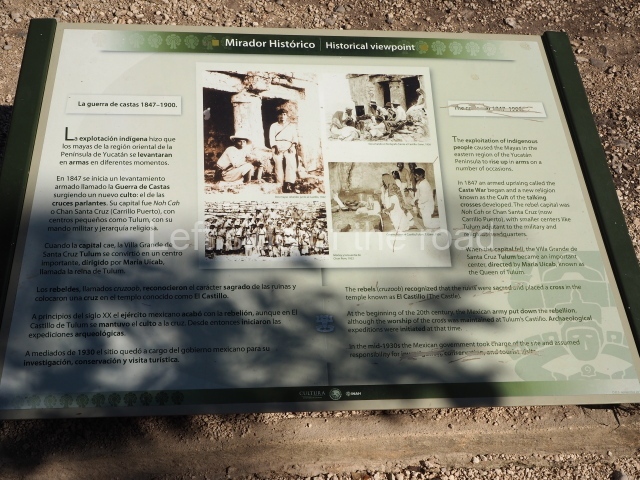

We owe the earliest mention of El Meco to Alice and Augustus Le Plongeon, who visited the site briefly in 1887 and described the plaza and main pyramid. In 1891, Teobert Maler published a few notes and a map, as well as the first known photograph of the central building. A few years later, in 1895, William Holmes made a short expedition to the site and contributed new descriptions and sketches, and also discovered two new serpent heads. The British researchers C. Arnold and F.K.T. Frost passed through the site between 1907 and 1908. The most important work of the early 20th century was conducted in 1918 by Samuel K. Lothrop, of the Carnegie Institution in Washington, who contributed descriptions and detailed drawings of the main structure. Thomas Gann, a member of the same expedition, published his impressions in 1924. Thirty years passed before the first stratigraphic wells were excavated, shedding light on the first ceramic sequence at the site; we owe this knowledge to William T. Sanders, who worked at the site in 1954. In the 1970s, a team of archaeologists from the INAH, led by Fernando Robles C. and Anthony P. Andrews conducted the first official excavations at the site, and since the 1990s Luis Leira G. (INAH) has been in charge of the works.

Pre-Hispanic history

The research conducted to date has confirmed that the first human occupation of El Meco dates back to the Early Classic, when it must have been a small fishing village that owed allegiance to a larger site further inland, such as Coba. Everything suggests that the site was abandoned for an interval of some 400 years and then reoccupied around 1000 to 1100 AD. Judging from the architectural style and ceramics corresponding to that period, the new population appears to have been of Itza and Cocom descent, from the western part of the Yucatan Peninsula. Between AD 1200 and the arrival of the Spaniards in the 16th century – namely, the period known as the Postclassic – El Meco experienced a construction boom and developed closer political and economic ties with all the sites on the east coast. We do not know the original name of the site. El Meco is a reference to the limp of a local resident in the 19th century who owned a coconut palm plantation near the lighthouse by the beach and whose nickname was adopted for the ruins. Some researchers have suggested that El Meco might be the Belma of the 16th century mentioned by the chronicler Oviedo y Valdes as the administrative centre of Ecab, one of the most important provinces in the region on the arrival of the Spaniards.

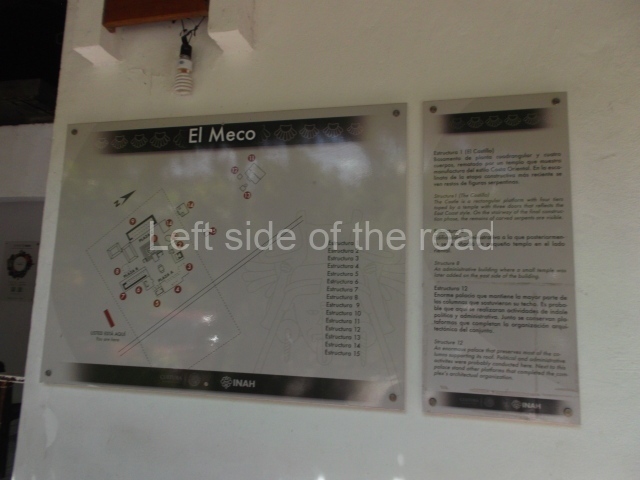

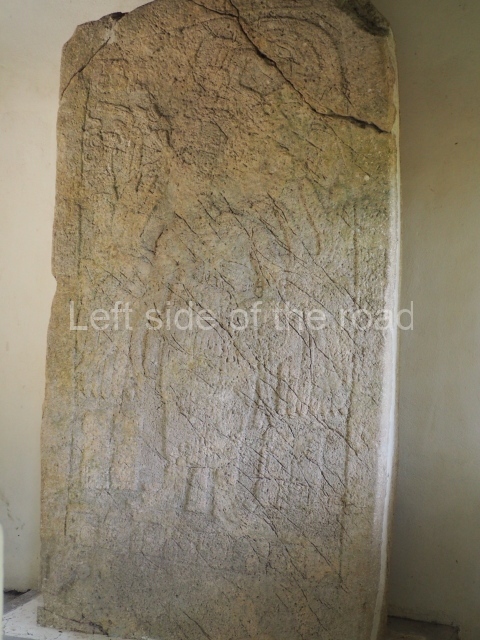

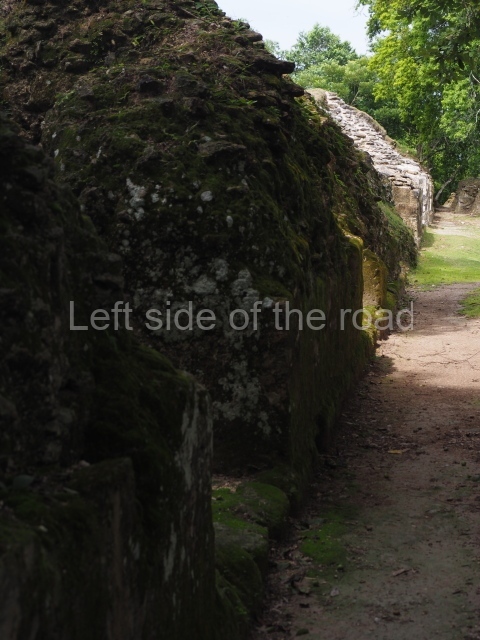

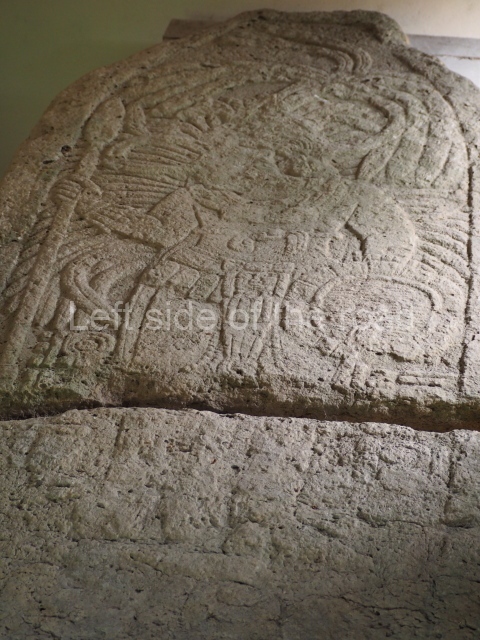

Site description

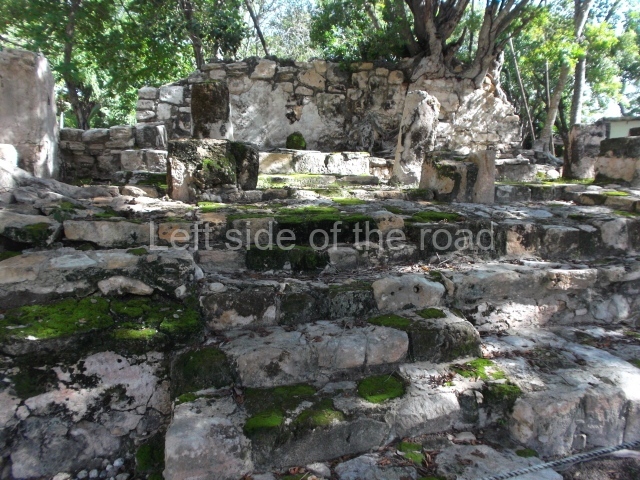

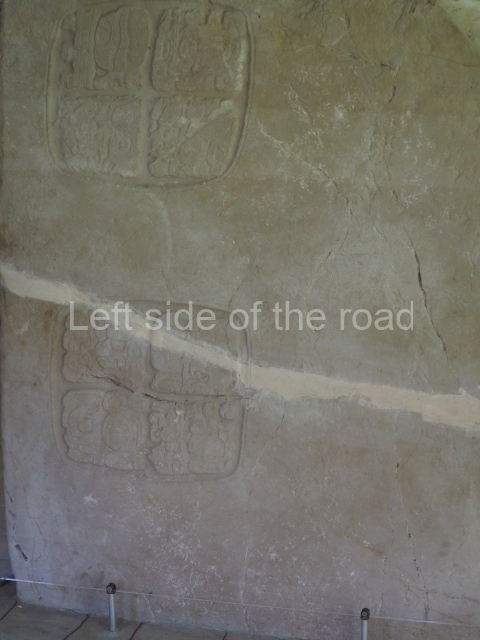

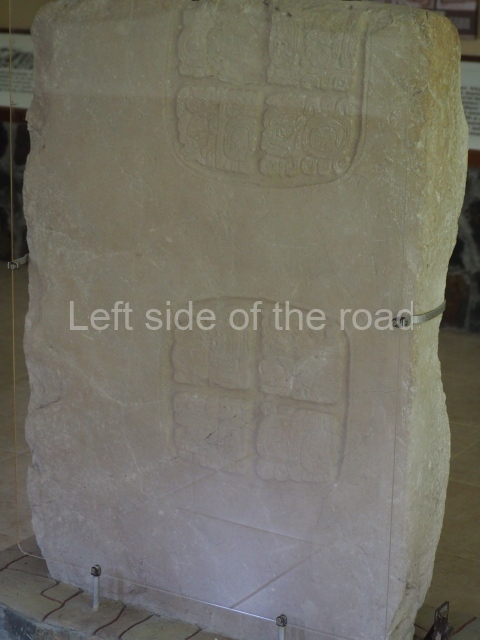

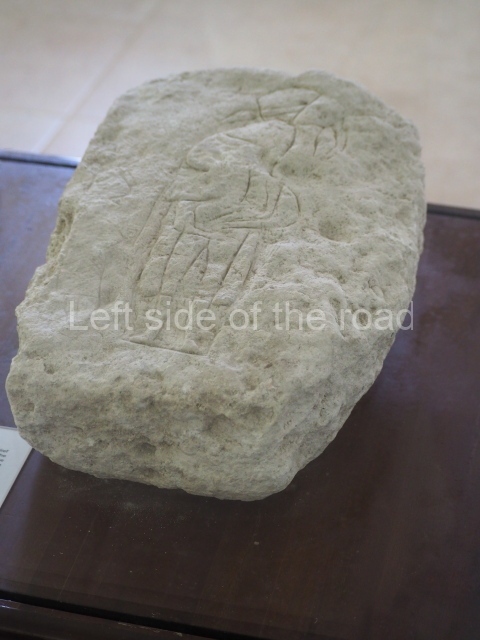

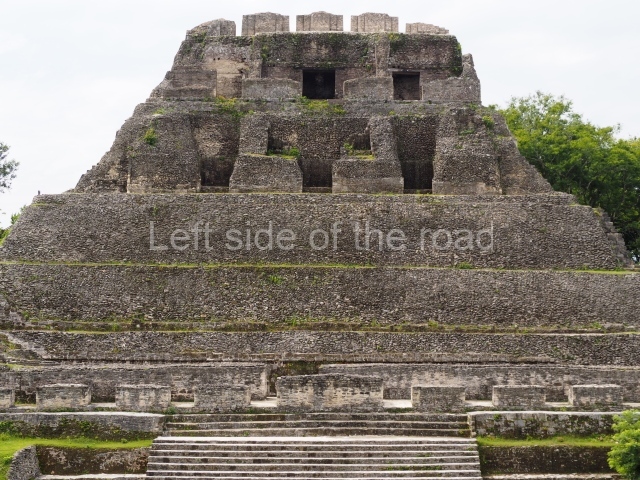

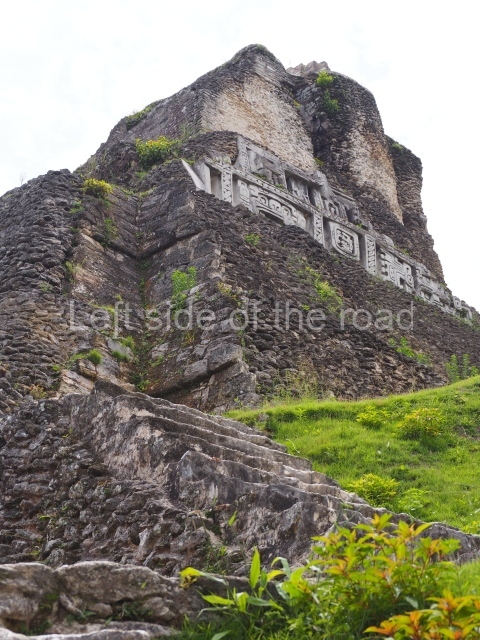

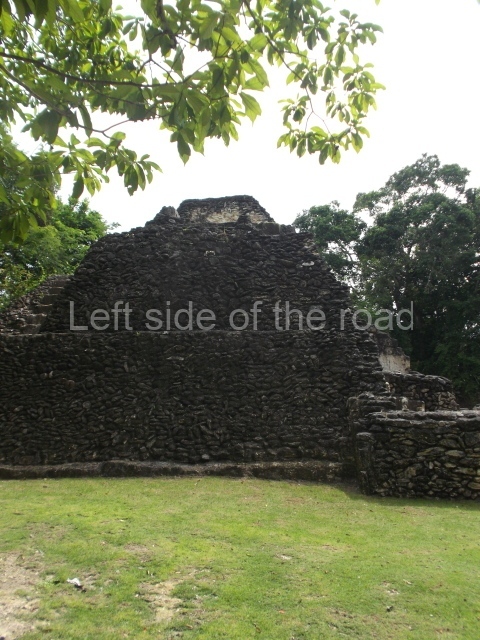

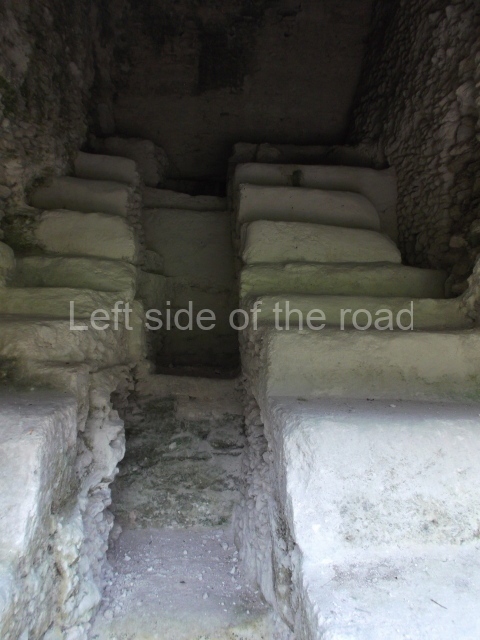

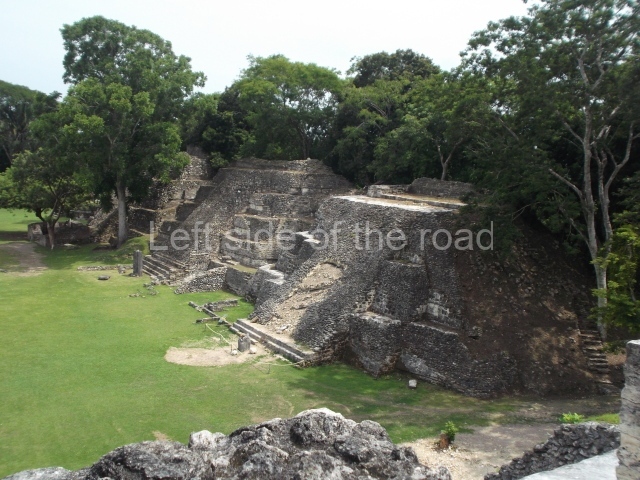

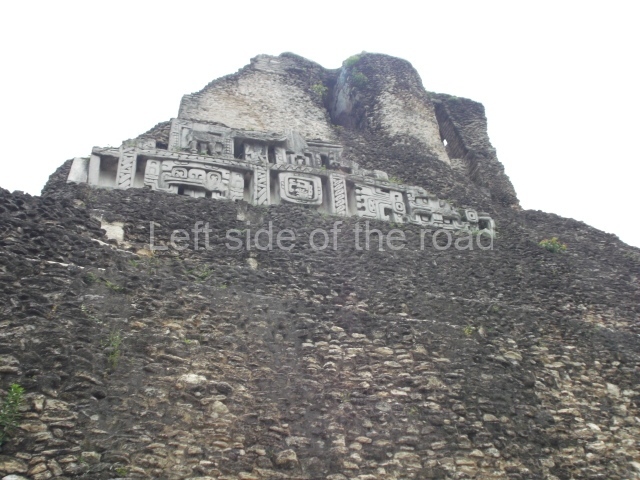

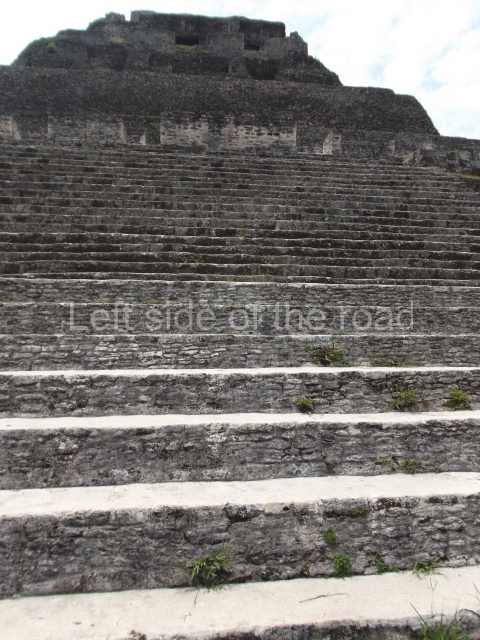

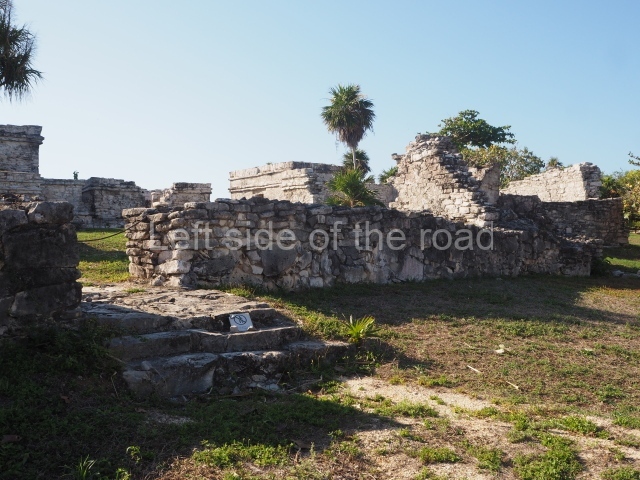

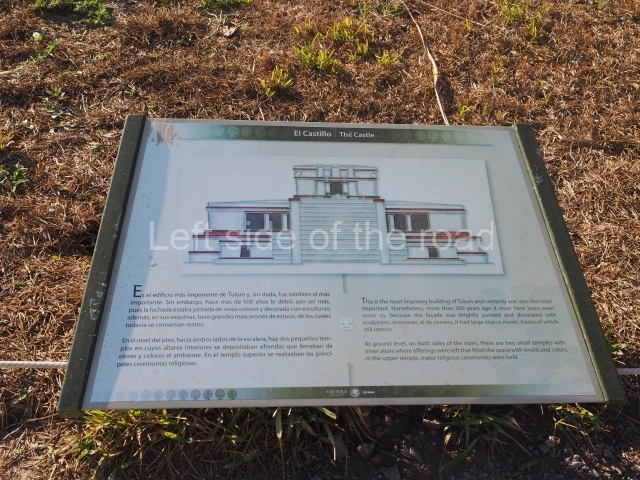

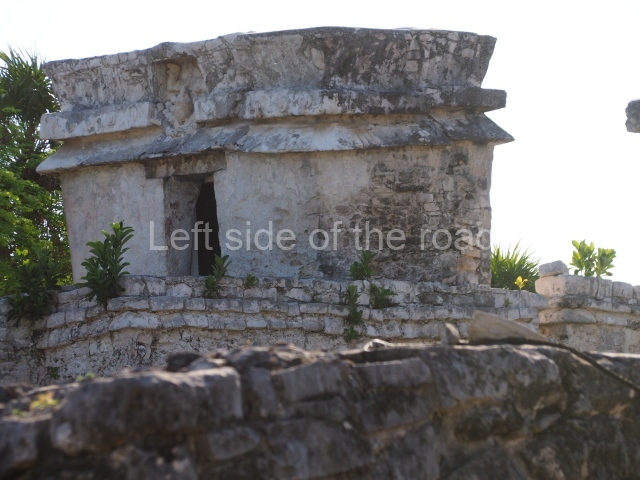

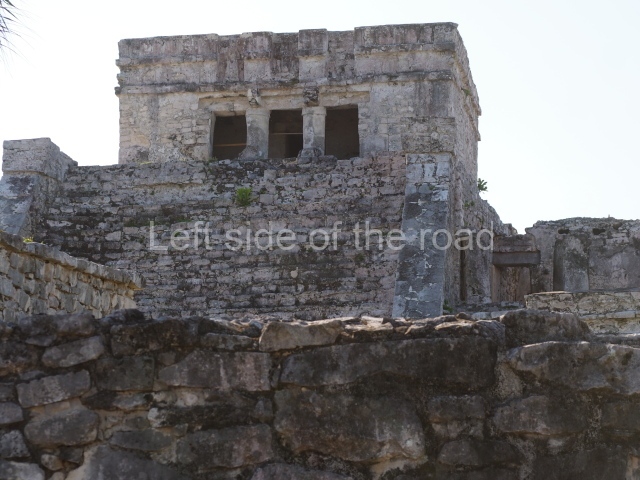

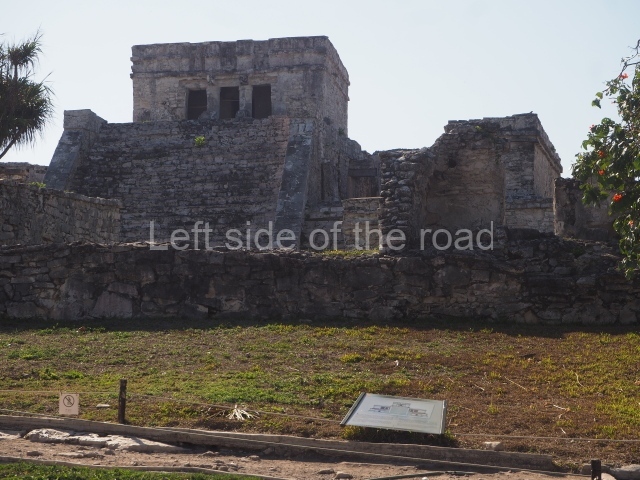

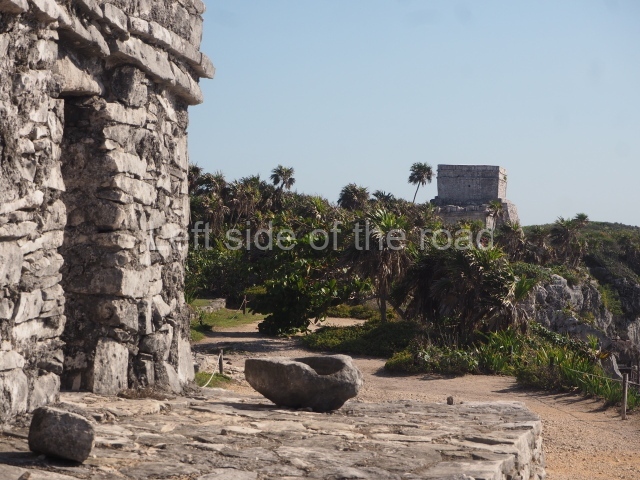

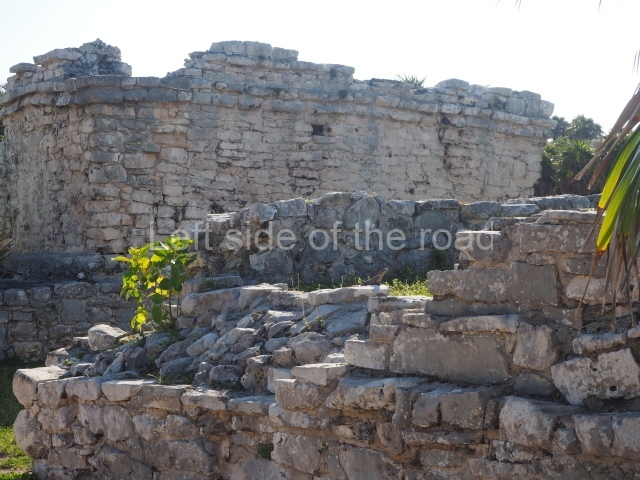

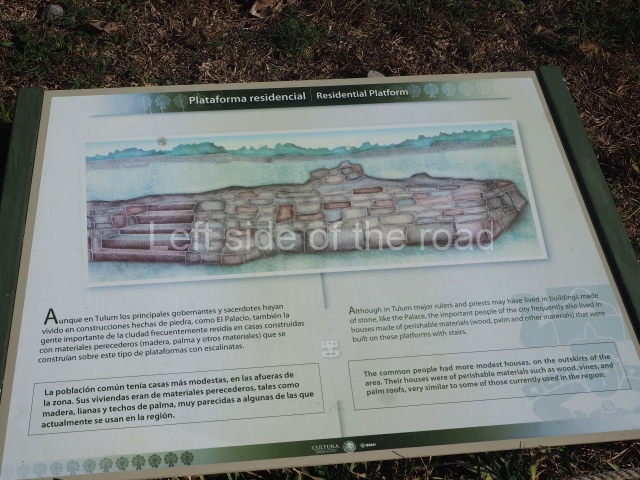

The orientation and layout of the buildings in the core area of El Meco confirm their dual ceremonial and administrative function. All of the constructions are arranged around a plaza, at the centre of which stands the most important structure of all, known as the Castillo. This building faces east, towards Isla Mujeres (‘Island of Women’), with which it maintained close ties. Square in plan and standing 12.50 m high, it is the tallest building on the north coast of Quintana Roo and probably served as a reference for the ancient seafaring Maya. It displays three construction phases and is composed of a four-tier platform with a balustraded stairway in the middle culminating in two serpent heads, nowadays greatly eroded and barely recognisable as such. At the top of the structure is a temple with a tripartite entrance in the East Coast style. The excavations revealed the existence of a substructure – a single-tier platform and a small temple with a single entrance. Nowadays, part of this substructure is exposed and visible on the west side of the building. Flanking the building are two constructions; the smaller of the two corresponds to a temple and the other, fronted by columns and small altars, probably to a residence. The architecture around the main plaza is defined by elongated buildings with hypostyle rooms, which may have been used for political or administrative purposes. Given the importance of the site as a commercial port, some of the buildings may well have served as warehouses for products or a market.

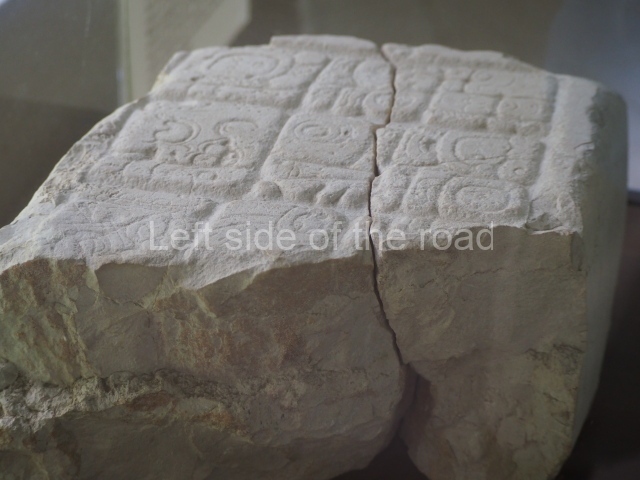

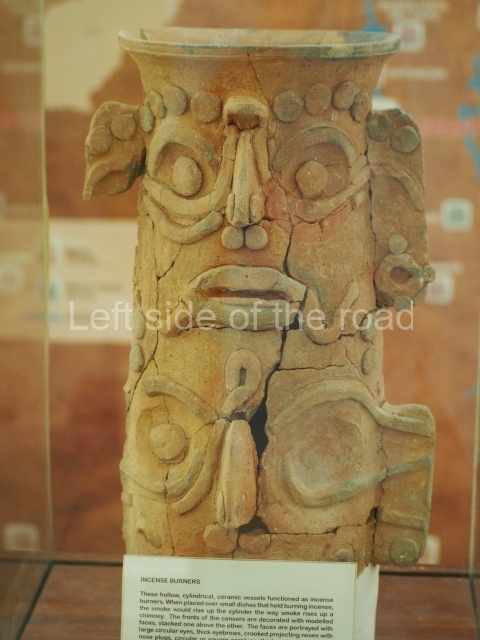

Ceramics

Three ceramic groups have been identified at El Meco, providing us with an insight into the cultural development of the site:

Cochuah ceramic group (AD 400-600).

This is the earliest manifestation of human activity and the ceramics found suggest that during the Early Classic their relations were limited exclusively to sites in the north of Quintana Roo.

Hocaba-sotuta ceramic group (AD 1000-1200).

Between the former period and this one, the site was vacated. During this time, El Meco appears to have maintained relations with communities in the Peten/Belize region.

Tases ceramic group (AD 1200-late 16th century).

This period corresponds to the last pre-Hispanic occupation and increased construction activity. The site must have had connections with sites on the east coast of Quintana Roo, although there are certain stylistic similarities with the architecture of the western part of the peninsula. El Meco was abandoned in the late 16th century, like most of the sites on the east coast, due to the new economic, political and religious patterns that accompanied the Spanish Conquest.

Importance and relations

El Meco almost certainly operated as a religious centre during the Postclassic. Due to its coastal location and close ties with Isla Mujeres, it may well have played an important role as a trading port and part of an important trade network along the coast of Quintana Roo during the Postclassic.

Maria Jose Con Uribe

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 433-435.

1. The Castle; 2. Structure 3; 3. Structure 6; 4. Structre 8; 5. Structure 12; 6. Structure 18.

How to get there:

From Cancun. Combis leave Parque el Crucero to the north of the main ADO bus station in downtown Cancun. Their destination is Puerto Juarez and/or Puerto Sam. It’s a short 10-15 minute journey. Cost M$10 each way.

GPS:

21d 12’ 38” N

86d 48” 05” W

Entrance:

M$70