Rizhskaya – Line 6 – Mikhail (Vokabre) Shcherbakov

More on the USSR

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery

Moscow Metro – Rizhskaya – Line 6

Rizhskaya (Russian: Рижская) is a Moscow Metro station in the Meshchansky District, North-Eastern Administrative Okrug, Moscow. It is on the Kaluzhsko-Rizhskaya Line, between Prospekt Mira and Alekseyevskaya stations. It is named after the nearby Rizhsky railway station (which was named after and serves trains to the Latvian capital, Riga) and was designed by Latvian architects Artūrs Reinfelds and Vaidelotis Apsītis.

Rizhskaya – Line 6 – 02

The brightly coloured Latvian ceramics employed throughout the station make it instantly recognizable. The pylons, which follow the curve of the station tube, are faced with reddish-brown tile and sandwiched between piers faced with lemon yellow tile and decorated with gold-coloured cornices. The ventilation grilles above the pylons are decorated with the coat of arms of the Latvian SSR. The station opened on 1 May 1958.

Rizhskaya – Line 6 – 01

The round vestibule, which was designed by S.M. Kravets, Yu.A. Kolesnikova, and G.E. Golubev, is located on the east side of Prospekt Mira at Rizhskaya Square.

Rizhskaya – Line 6 – 03

The station reopened after reconstruction on 7 May 2022. A transfer to the Bolshaya Koltsevaya line at Rizhskaya was opened on 1 March 2023.

2004 terrorist bombing

The street outside of the entrance to the Rizhskaya station was the site of a terrorist attack by Chechen separatists that occurred shortly after 8 pm on 31 August 2004, in which a bomb was detonated killing 10 people and injuring another 50, some 30 of them seriously. The suicide bombing was thought initially to have been carried out by Roza Nagayeva, but she in fact took part in the Beslan school siege in North Ossetia that started the next day, and was herself killed when the school was stormed several days later.

Text above from Wikipedia

Rizhskaya

Date of opening;

1st May 1958

Construction of the station;

deep, pier, three-span

Architects of the underground part;

A. Reinfelds and V. Anpsitis

Rizhskaya is constructively similar to two previous stations but much differs by decoration. It is an absolutely ceramic station. The walls are faced with light yellow tiles while the pylons are with yolk-yellow and claret-coloured tiles. So the station is called ‘fried eggs with bacon’.

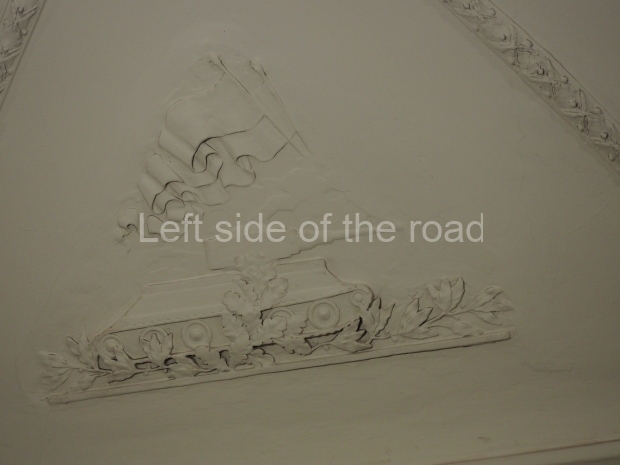

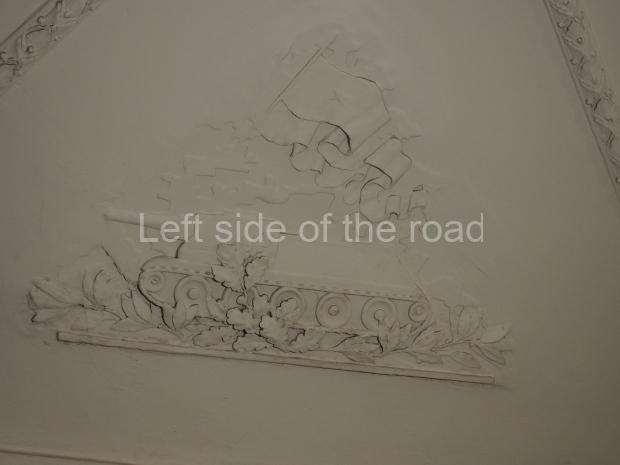

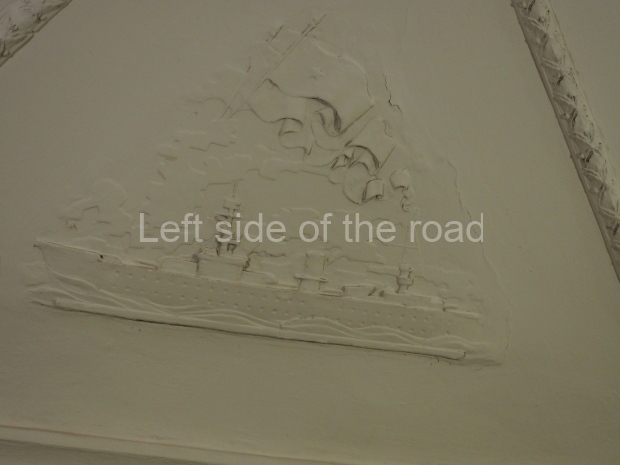

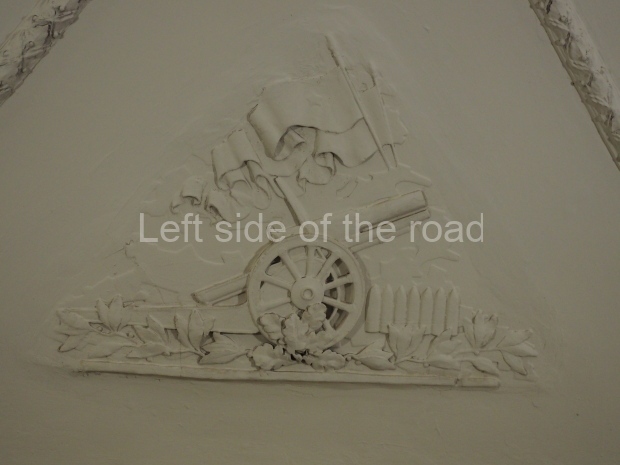

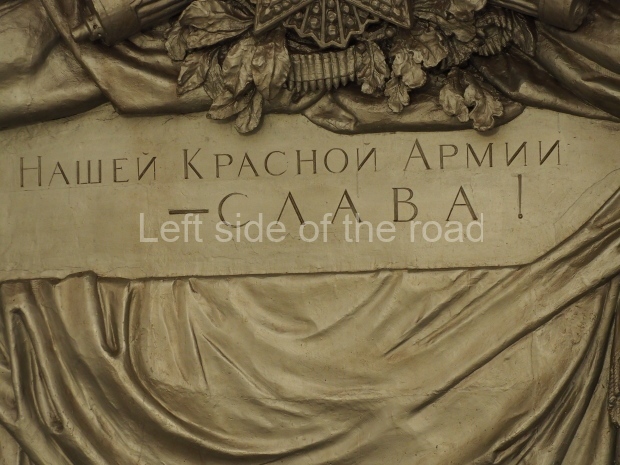

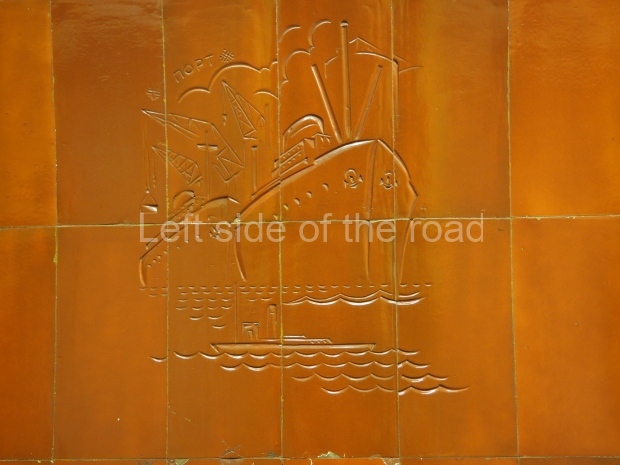

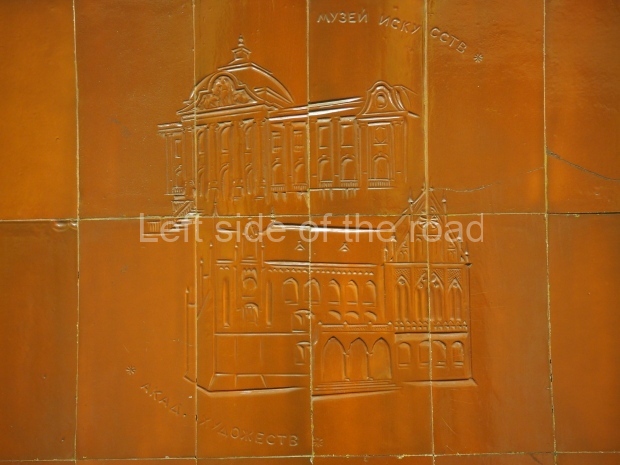

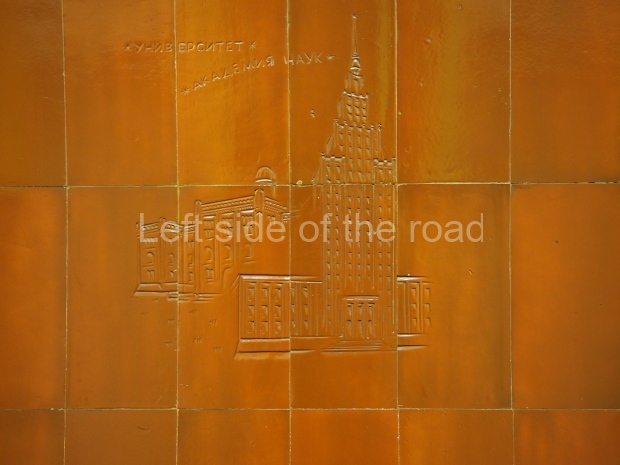

Hardly visible very thin high relieves on raw ceramics decorate the claret-coloured surfaces of the side of the central hall. They show well-known architectural and industrial structures of Riga and sights of other Latvian cities, such as House of Government, House of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Latvia, old Riga, Museum of Arts, Academy of Arts, heat power station, VEF, port, central kolkhoz market, Kemeri (region of Jurmala), seashore. There are also silhouettes of Moscow State University and Academy of Sciences on the first pylon of the western end that manifests the inviolable relations between Riga and Moscow. The Latvian national colouring is highlighted with ornaments on the sides of station benches and tiles facing the platform walls.

Text from Moscow Metro 1935-2005, p77

Location:

GPS:

55.7936°N

37.6362°E

Depth:

46 metres (151ft)

Opened:

1 May 1958

More on the USSR

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery