Tobacco Factory – Durres

The work of the Albanian Lapidar Survey, in documenting and quantifying the monuments throughout the country, has produced an invaluable resource for those who have an interest in the Albanian version of Socialist Realism. However, due to time, resources and the difficulty of identifying the vast amount of examples of a new form of popular expression (made even more difficult with the criminal destruction of the archives of the Albanian League of Writers and Artists) many unique pieces of art were not part of the survey. The concrete bas-relief on the facade of the (former ‘Stamles’) Tobacco Factory, close to the seafront in Durrës, was, therefore, one of those not documented and now it has gone (unless someone with foresight was able to save it) forever.

Once you start to look at the history of Albania after the invasion of the Italian Fascists in April 1939 (which coincided with the fleeing of the self-proclaimed ‘king’ and despot Zog – to live a life of luxury and safety in a mansion in Britain – he even ran away from the capital city to a house in the countryside when the bombs started to fall on London during the Blitz) you realise the bravery of the Albanian working class – who couldn’t run anywhere – and their preparedness to stand up against the armed fascist invaders, as the tobacco workers did in their strike in 1940.

It was probably a challenge to the Italian soldiers (conscripted workers and peasants) to be faced with unarmed workers on the streets the invader declared they controlled. The German Nazi invaders (who replaced the Italians in 1943) were more prepared to murder civilians than the Italians – as they did at Borovë and Uznovë, amongst other locations – but the Italians seemed reluctant to gun down Albanian workers on the streets of Durrës.

That sign of weakness (a contradiction that besets capitalism, imperialism and Fascism if the working class can just but recognise it) can be used by the politically organised working class if they accept the idea, which was later encapsulated in the slogan of Mao Tse-tung 20 years later, that ‘All imperialists are paper tigers’. This means that the enemy is only strong if we accept they are. Challenge them and they will retreat, even though we have to accept that they will lash out with viciousness in the process. They use fear as a control mechanism, if you don’t fear them they are no more than thugs with weapons, afraid that their ‘Emperors new clothes’ will be seem as they are, just a figment of the imagination.

But we have to go back a few years to understand why things were such after the country was invaded by the Italian Fascists.

Although this history is gradually being obliterated in Albania there was a tradition during the socialist period, from 1944 till 1990, to celebrate, commemorate and remember those people, those events of the past that had played a part in the liberation of Albania from foreign domination. The fact that these physical declarations of the country’s past are disappearing is only a manifestation of the disappearance of any semblance of independence the Albania people had achieved and only maintained for a little over 45 years.

As Marx wrote way back in the 19th century the capitalists create their own grave diggers and a plaque on the building celebrates this, not the establishment of the factory as such but more the fact that by building and opening the tobacco factory, in a predominantly peasant country in 1924, the Stamles company was preparing the groundwork for its destruction.

One of the plaques, which was directly beneath the frieze, on the facade of the factory had the following:

Ne prill te vitit 1924 u ngrit ketu e para fabrike e cigareve, klasa punetore e se ciles u be çerdhe lufte per te drejtat shoqerore dhe e levizjes nacionalçlirimtare.

This translates as:

In April 1924 the first cigarette factory was established here which, for the working class, became a nursery in the battle for social rights and of the National Liberation Movement.

In the 21st century this small building would be barely considered a workshop let alone a factory but in 1924 this was a huge step forward in terms of ‘development’ for the people of Durrës. This would have been seen as part of the modernisation of the port city. A country that had previously only produced the primary means of production was now turning what they had grown in the countryside into a finished product which had added value and could be exported to other, external markets. How successful the Stamles company was in this field I don’t know but with the establishment of such companies there was, at least, a potential to take Albania out of the situation of being a client state.

If it didn’t do that for capitalism – the forces against them too great in nearby neighbours, especially Greece and Italy – at least it taught the workers a lesson. They might have earned more but their security would not have been any greater. The ‘Great Depression’ of the later 1920s and early 30s would have introduced these ‘young’ industrial workers to the reality of capitalism – another crisis is always around the corner, then and now.

But then it would also have been a school of revolution. Lacking in present day capitalist societies in Albania in the 1920s/30s there was a revolutionary movement seeking to change the old world order.

That movement, initially through trade unions, was able to create a situation where, in 1940, the workers, both men and women, of the tobacco factory were prepared, and had the courage, to go on strike during the Fascist occupation of their town and country. I won’t go as far as saying this was unique but I can’t think of many other countries invaded and occupied by the Fascists at the time where the workers went on strike – and this bravery and disregard for the possible consequences, of the Albanian people, was the reason they were able to free their country of the invaders with their own efforts.

Another plaque that used to be on the side of the building (situated next to one of the ground floor windows, just as the wall of the building curved around the corner) celebrated that strike:

Me 12 korrik 1940 punetoret dhe punetoret e shoqerise kapitaliste ‘Stamles’ nen drejtimin e komunisteve te grupeve, bene nje greve te madhe, e cila qe nje aksion i rendesishem politik antifashiste klasor.

In English:

On 12 July 1940 the employees and workers of capitalist society ‘STAMLES’, under the leadership of communist groups, went of a great strike, which was an important political, antifascist class action.

This was probably placed on the building quite soon after National Liberation on 29th November 1944. It would have been during Albania’s Cultural Revolution, starting in the mid-60s, that plans for the bas-relief would have been formulated.

Now to the sculpture itself. The frieze is a pictorial representation of that event and when I saw it for the first, and only time, in November 2011, it looked sad and neglected. I don’t know exactly when the factory ceased production but I wouldn’t be surprised to find that it was very soon after the counter-revolution gained control in the early 1990s.

Failures of the Party of Labour of Albania as the leader of the workers of the country, together with their inability to counter the foreign-controlled attacks on the socialist structure of the society provoked shortages and instability that caused too many Albanians to think that the ‘grass was greener on the other side of the fence’.

Durrës is on the coast. It was the country’s most important port. Contact with Italy – the old imperialist, invading, dominating power (going back to the time of the Roman Empire) was attractive. The ‘shortages’ encouraged by the reactionaries (by scaremongering and active sabotage) meant that people became disillusioned with their homeland and ‘wanted’ to leave. Anti-communism meant that Albanians, leaving to seek ‘freedom’ were ‘welcomed’. The opportunity arose, they took it, including the workers from the tobacco factory.

The reason I mention this before the actual sculpture itself is that this is all part of the story. People have a reasonably paid job making a product which has health issues but at least they are being paid. Then there’s a growing panic within society. If you don’t leave first you will be too late. Shortages in most societies aren’t caused by shortages but by panic that there will be a shortage.

People leave in droves, the tobacco factory closes. No workers no production. People start to worry that if they don’t get to the trough first there will be nothing left. Those who don’t leave, for whatever reason, have nothing constructive to do so they become destructive – they loot. When all the machinery has been taken they take away the windows. This mindless destruction of much that had been built since 1944 was widespread and included museums and libraries. If you travel around the country you will see innumerable examples of abandoned, ossified, infrastructure.

That’s what they did in Durrës to the tobacco factory and the blind, empty windows meant that the dirt from inside was swirled around by the wind from the sea and it settled on top of the bas-relief, located on the top of the ground floor of the facade of the factory facing the old city walls. The grey concrete has a black cap. This does make it slightly difficult to make out exactly what is depicted but not impossible.

What we have is a demonstration. This demonstration has two principled causes. The perpetual demand against the employers for a greater share of the profits, that is, higher wages, and in the case of Durrës in 1940, a strike against Italian Fascist domination of their city.

This is seen in the banners carried by the men and women on the street. But there’s an important positioning of these demands. In a capitalist, bourgeois society the demands of the workers are ‘selfish’, immediate, economic, but here the demand at the front of the demonstration, where the workers will come in conflict with the Italian invaders, the most important slogan is:

‘Poshte Fashizmi’, meaning ‘Down with Fascism’.

Yes, the economic demands of the workers are important. A Fascist invading country is unlikely to be prepared to offer higher wages but the task of a trade union is to fight for the rights of its members but this always depends on the circumstances at a particular time. There is no way workers will get improved conditions unless they deal with the most important and principal contradiction, and in Durrës, in Albania, in 1940 that was Italian Fascism, and its destruction and eviction from the country.

So this economic banner is further back along the frieze – and it must be remembered we are talking of a bas-relief that was probably about 10 metres long.

The second banner reads: ‘Kerkojme ngritje e pagave’, literally demanding a wage increase.

We have the majority of the participants in the demonstrating looking and moving in the same direction, i.e., marching and looking, from right to left. We don’t see the opposition, but in a painting by Sali Xhixha above, we can see that they would have been Italian soldiers. They would have been confused about what to do. They are faced with angry men and women, shouting and screaming at them in a language they don’t understand. In such circumstances it is not unknown for a frightened soldier to fire and then precipitate a slaughter but I’m not aware of any injuries during this strike or demonstration.

There are 23 definable figures on the frieze and most of their features were clear to the viewer after years on the building with half of those in neglect. The majority are male but I think it’s possible to make out 7 women involved in the action. This would have been the case in the 1930s, new industry taking both men and women from the countryside and, if we consider cigarette manufacture in different parts of the world at the time, women would have been a substantial part of the workforce.

One aspect which makes this frieze different from some of the other lapidars so far described and that is we are left in no doubt that these people are workers. Their clothing and hair styles are of a town dweller. There is no sign of the traditional clothing still worn in the countryside at that time and none of the women are wearing head scarves – even capitalism offers women a certain amount of ’emancipation’. Another characteristic that is different from other sculptures is that they are all, both men and women, of a similar generation, there’s no obviously older people and only a couple of young boys and girls.

In the front rank are two men. The one at the back is wearing a worker’s cap, his shirt is loose and fluttering open, giving a sense of movement. His anger is shown by the fact that he is shouting and he has his right arm raised with a clenched fist, although unarmed his whole body language is presenting a threat to the fascist authorities. Beside him the young man is side on to the opposition, his right shoulder leading with his right arm raised towards his left shoulder, the clenched fist seeming about to lash out against those unseen forces of occupation. He is bare-headed.

Behind them is a group of three, two women and a man, slanted up from right to left. All of them have their mouths open, shouting slogans, taunts or obscenities against the Fascists. We can only see part of the clothing of the woman closest to us and she wears a light shirt that a worker would be wearing in the hot Adriatic summer. Above their heads are five raised, clenched fists – only two possibly belonging to this group of three. Here the artist is indicating that although he has only depicted 23 demonstrators there were many more out of view.

Next, as we move further from the front line, we see the ‘Down will Fascism’ banner, mentioned before. In front of that, his head obscuring a small section of that banner, is another male. His attitude is different from those we’ve seen so far. His body is front on to the viewer and his head is turned slightly towards the front of the demonstration – but although there is determination on his face he is not shouting and neither is he making any threatening gesture. His right hand is gripping the lapel of his jacket and his left arm is hanging loose, the hand outside the limits of the tableau.

The next is a head and shoulders image of a round-faced male. He is even more impassive than the previous striker. He’s looking out at the viewer and doesn’t show that he is involved in what is going on around him. I’m not really sure what he is doing here as he shows no anger or any emotion at all.

I’ve tried to work out why these two are even in the picture. Every other person depicted is interacting either with the Fascists or each other, these two, on the other hand, seem no more than bystanders, not involved with the events unfolding. As there was so limited a space for the bas-relief I can’t work out why time, effort and space has been spent on images that add nothing to the story. I’ll accept that in such demonstrations not everyone is fully engaged but such distance is transitory. On a work of art such as this one their inactivity is recorded, literally, in stone.

The next figure is the opposite. This is the figure that looks behind him, away from the point of conflict with Fascists, but plays the crucial role of encouraging others to get closer, to come and join the action, as well as giving the impression that there are many more that were involved in the demonstration but which it is impossible to depict on such a finite space. (This is a fairly common trope of Albanian lapidars and monuments and, for example, can be seen on such diverse monuments as the Arch of Drashovice and in the Peze Martyrs’ Cemetery.) He is dressed in the normal clothing of a worker of the period. As we only see him from the waist up he is wearing a shirt and jacket. His shoulder faces the front of the demonstration, his torso faces the viewer, the right side of his head is in profile and his left arm is in the air above his head and his hand is wide open in a beckoning motion and his open, fluttering jacket provides an element of animation.

In the crescent that’s formed by his arm and head there are three other males, only their heads, but we are starting to get back to active participants in the action. The one that is closest to, and immediately behind, the striker encouraging others to join is looking towards the front but there’s no real animation in his look. Next to him we have another youngish man, in profile, who has his mouth open shouting slogans. Both these are bareheaded. The third of this small group is again in profile, again with his mouth open but what is different is that he is wearing a peaked cap. I wouldn’t have thought that such caps were normal wear for working class males at the time so perhaps here we have someone who has some official role in the factory, showing that it was an all-factory strike.

Above the heads of this group are three, clenched right fists, possibly from these men but also giving the impression that others are out of sight. Also here there’s a right hand raised in a mock-Fascist salute, the hand raised high and flat, pointed in the direction of the Italian soldiers.

The next in line is the torso of a woman, with her long hair taken up in braids, and wearing a shawl over her shoulders. Her left arm is bent and raised to the level of her head and her fist is clenched. She also has her mouth open in a shout.

Following the line, from right to left, of her raised fist are the heads of two women. They also have their hair taken up in braids, this presumably being a style common for working class women of the time. They are both in profile and are looking towards the front of the demonstration.

Above their heads is the forward edge of the banner demanding higher wages. It gets a bit crowded here. There’s the head of a male workers in front of the banner and below him there’s a larger figure of another male. He’s wearing a flat cap and is in profile, looking towards the back of the march, possibly talking to another male. He has his left arm raised, with the fist clenched and it’s possible to make out the muscles on his forearm.

To the right of the banner are further clenched fists raised in anger, two of a right hand and one of a left, there being no real consensus which arm should be raised in a Communist salute. Below the fists there’s the profile of another male striker and below him the torso of another male who is shown wearing a work apron, the first person so far depicted dressed in actual work gear.

Coming to the end of the sculpture now we have a line of three, from top to bottom, a female worker (again with her hair braided) and then the youngest of the whole frieze, a teenage boy and girl. The boy is full face and is just looking whilst the young girl has her mouth open shouting with the others. To enhance the impression that she is younger than the other women her long hair is worn in a pony tail with a ribbon tied at the end.

The final strikers are two males, both in profile. The higher one has his mouth open and his left arm raised as high as possible above his head, the fist clenched. His whole manner speaks of his anger at the situation. The last male is looking ahead and his left hand is grasping something flung over his shoulder.

The final image is one that declares that this is all going on in Durrës and that is the top of a crenellated tower. This is La Torra, a tower which was constructed as part of the city walls when the city was occupied by the Venetians during the 15th century. The tobacco factory used to sit just across the road from the southern part of the wall and the tower was only about fifty metres away. (The tower has now been converted into a bar, everything that can possibly be privatised going into private hands.) The crest for the Bashkia (local government) of Durrës also has the three crenellations of the tower as its central image.

The remainder of the bas-relief is text. In Albanian:

12 korrik 1940

Greva e punetoreve te ‘Stamles’ nje nga aksionet me te medha te qendreses antifashiste te klases punetore te Durrësit

This translates as:

July 12, 1940

The strike of the ‘STAMLES’ workers, one of the greatest acts of working class, antifascist resistance in Durrës

I was unable to find any date or indication of the name of the sculptor on this concrete bas-relief.

There was one more plaque on the wall under the sculpture. This was a war memorial, to those Partisans who were once workers at the tobacco factory. This reads:

Lavdi te perjeteshme deshmoreve te luftes nacionalçlirimtare, ish punetore te fabrikes se cigareve

In English:

Eternal glory to the Martyrs of the National Liberation War, former workers of the cigarette factory

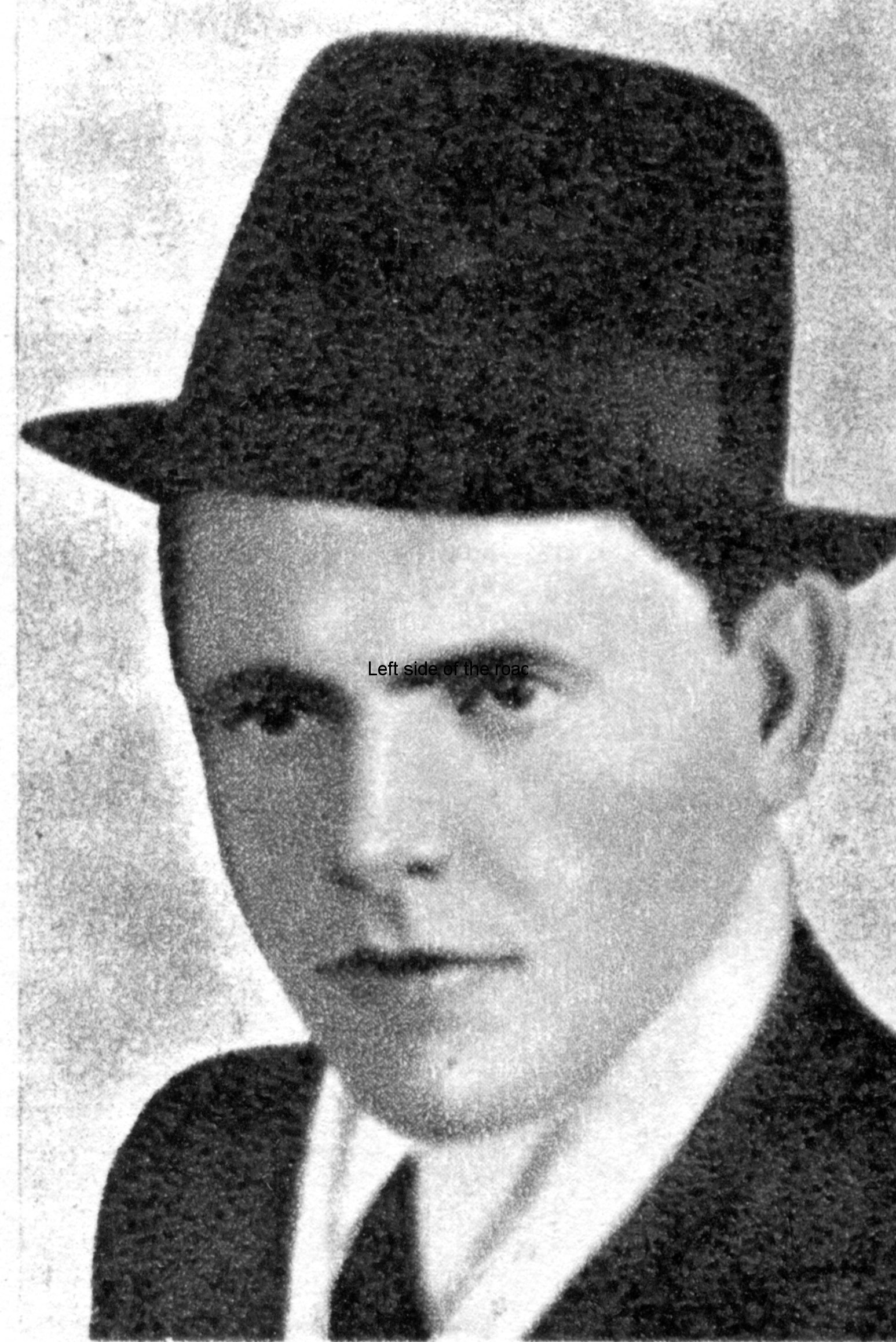

In then lists 19 names, the top one of which is Maliq Muça, who had been declared Hero i Popullit (a Hero of the People). It’s not surprising that a factory where Communists had been working, even before the Italian invasion of April 1939, would also provide volunteers and fighters for the Partisan army.

Maliq was a Communist and he joined the Peze Çeta (the first guerrilla group to be established in the country, even before the declaration of a War of National Liberation at the Peze Conference of September 1942) so was a seasoned Partisan fighter. He was involved in confrontations with the invading Fascists, first the Italian and then the German, in many parts of the country. On 1st June 1944 his company of about 80 partisans was surrounded in the hamlet of Germaj, near Kavaja (to the south of Durrës). Overnight a combined force of German and Ballist (Nationalist collaborators) were able to call in reinforcements and thereby greatly outnumbered the Partisans. The Albanians refused to surrender and it was with a last grenade that a seriously injured Maliq was able to kill an officer and four other soldiers. He was also killed in the explosion.

I have no idea of the fate of this plaque, assuming it was destroyed at the same time as the bas-relief.

And now the sculpture has gone! Forever? As far as I’ve been able to understand, yes. It’s in one piece and it would take a lot of care and knowledge of such removal for it to have been done without causing irreparable damage. Even if the expertise was available the economic (and more importantly) political will wouldn’t have been, even though Durrës is nominally a Social-Democrat Bashkia. A possible place for it would have been the city’s Archaeological Museum (that was undergoing a major renovation at the time of the demolition of the factory) but that continues to concentrate on Ancient Roman artefacts, allowing no space for anything cultural from the Socialist period.

Durrës still has an art gallery (located in the main square by the town hall) where it is possible to see, when there’s no special exhibition taking place, examples of Socialist Realist paintings and sculptures but the museum that used to exist above the War Memorial was taken over by a British based Non-government Organisation as a library – in a city where there would have been libraries in every district, until looted when the country went mad in the early 1990s. So there was no obvious home for the sculpture once the building was no more.

So what has replaced the derelict factory? A monstrosity. This is the Albanian College Durrës, a huge building with neoclassical pretensions and totally out of place in this part of town. This is a theme that’s being repeated throughout the country. Private educational institutes claiming their credentials with the construction of enormous buildings – quantity surpassing quality.