The Albanian Cultural Revolution

Art as a means of promoting Socialism in Albania

Socialist mosaics and bas reliefs in Albania

In order that the Albanian Lapidar Survey didn’t become open ended many public works of art that had been created during the Socialist period (1944-1990) were not recorded. However, in my travels I have encountered many of these and have treated them in the same, hopefully, thorough manner as I have the ‘official’ lapidars.

‘The Albanians’ Mosaic, National Historical Museum, Tirana

‘The Albanians’ mosaic on National Historical Museum, Tirana, is one of the finest examples of late Albanian Socialist Realism still to be seen in the country.

Political Vandalism and ‘The Albanians’ Mosaic in Tirana

The wonderful and impressive ‘The Albanians’ Mosaic, which has looked down on Skenderbeu Square, in the centre of Tirana, from above the entrance of the National Historical Museum since 1982, is starting to show it’s age. Less it’s age, in fact, but really the signs of intentional neglect which is tantamount to an act of political vandalism.

Restoration of ‘The Albanians’ – National Historical Museum, Tirana – or not

For the second time in less than a decade the façade of the National Historical Museum in Tirana is obscured by scaffolding and sheeting. As on the previous occasion (in 2012) the reason is, supposedly, for the renovation of the ‘The Albanians’, the huge mosaic that celebrates and commemorates the struggle for independence through the ages, the victory over Fascism and the construction of Socialism.

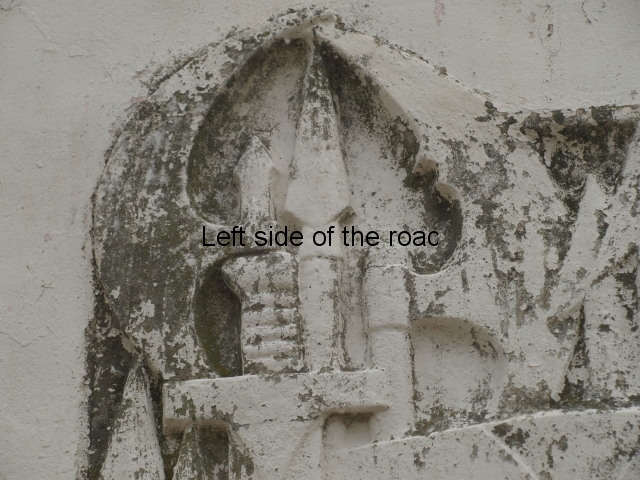

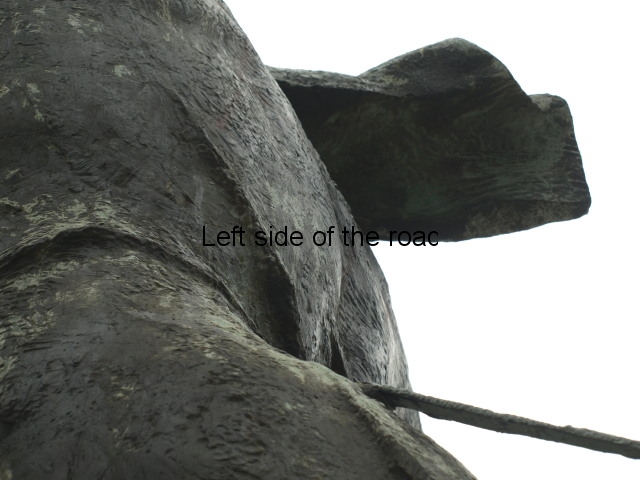

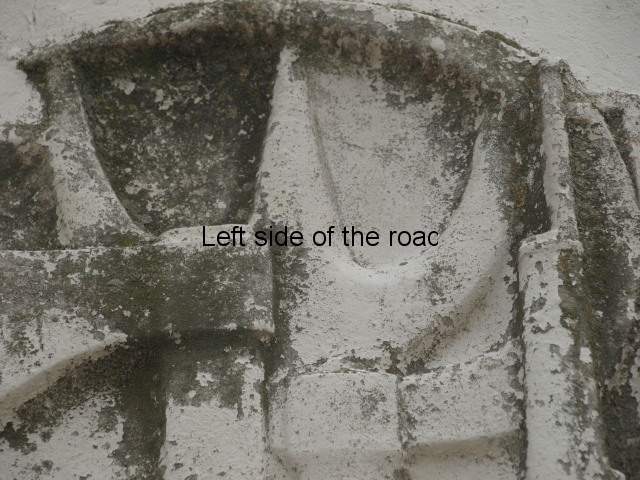

The bas reliefs and mosaics of the Vlora Palace of Sport

Although they are being neglected, and sometimes need dedication and determination to view them, there are still a number of artistic works from the Socialist period on many of what would have been public buildings. The most impressive (and becoming one of the most neglected) is the grand mosaic on the façade of the National Historical Museum in Tirana. Another example, which can easily be missed, is the bas-relief on both the north and south sides of the Palace of Sport in the town of Vlora. Even more easily missed are the two interior mosaics on either side of what would have been, in the past, the main entrance to this sports centre.

Bashkia Mosaic – Ura Vajgurore

The more I see of them the more I like the mosaics that were created in the Socialist period of Albania’s history. In many ways they capture a feeling of optimism and hope for the future which other art forms just can’t achieve. Yes, paintings can do that but the very scale of mosaics, out in the public view all the time, just seems more immediate. Mosaics have been around for a long time but in the past representing non-existent, mythical goods or the ‘rich and famous’. Those created in Albania in the 1970s and 1980s put the working class and peasantry into the forefront, showing that their lives are important and, if they but know it and chose to take on the task, that a better future will be theirs. Such is the mosaic on the façade of the Bashkia (Town Hall) of Ura Vajguror, between Berat and Kucove, in the centre of the country.

Socialist Albania was a colourful place in its time. Banners would decorate cities on anniversaries of important occasions, such as the Day of Liberation from Fascism, and when conferences and congresses were taking place banners and posters would celebrate these events. Slogans, often quotes from Marxist-Leninist leaders, would call upon the people to work to build Socialism in opposition to a hostile world surrounding the small Balkan country. Many of these symbols of the building of a new society were temporary and would be replaced when another anniversary arose or a different meeting was taking place. However, there were a number of more permanent works of art transmitting this message and one of them is the bas-relief over the main entrance to the local Kukesi Radio Station in the eastern town of Kukes.

There are more than six hundred lapidars so far listed by the Albanian Lapidar Survey but they are not the only examples of Socialist Realist Art that tell the story of the country, especially after Independence in 1944. Although a considerable number of lapidars are in a sorry state, whether due to neglect or outright political vandalism, there seems to be a move, at present, to ‘preserve’ those which are still in existence. However, I’m not aware of a similar programme (whether nationally or locally organised) that pays attention to the many statues, mosaics and panels that celebrate the achievements of the people. The panel to the miners in the small village of Krrabë is one such example.

The work of the Albanian Lapidar Survey, in documenting and quantifying the monuments throughout the country, has produced an invaluable resource for those who have an interest in the Albanian version of Socialist Realism. However, due to time, resources and the difficulty of identifying the vast amount of examples of a new form of popular expression (made even more difficult with the criminal destruction of the archives of the Albanian League of Writers and Artists) many unique pieces of art were not part of the survey. The concrete bas-relief on the façade of the (former ‘Stamles’) Tobacco Factory, close to the seafront in Durrës, was, therefore, one of those not documented and now it has gone (unless someone with foresight was able to save it) forever.

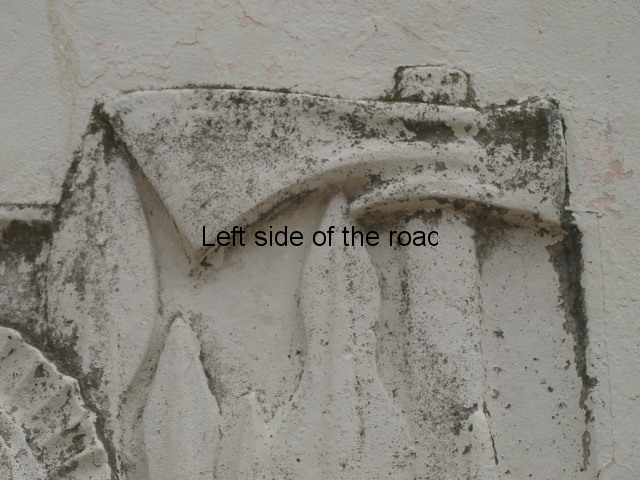

Gjirokastra College Bas Relief

This small relief, at the bottom of the stairs into a high school in the old part of Gjirokastra, commemorates an event in 1942 when the local students from the gymnasium (college), together with their teachers, demonstrated against, and clashed with, the occupying Italian fascist forces.

The overwhelming number of Socialist Realist monuments in Albania are constructed from either concrete or bronze. However, there are occasional variations from this norm and there are a few mosaics (though not on the massive scale of ‘The Albanians’ on the National History Museum in Tirana) including those in Bestrove, Llogara National Park and at the Durrës War Memorial.

Mosaics play a small part in the history of Albanian lapidars but when they do appear they do so in an impressive and memorable manner. Although not strictly a lapidar the most impressive is the huge the ‘Albanian’ mosaic on the façade of the National Historical Museum in Tirana. Also interesting and worth a visit is the mosaic in the Martyrs’ Cemetery of Durrës. Each of these have their distinctive aspects and the mosaic, near the village of Bestrovë close to Vlorë, is another unique monument in its own right.

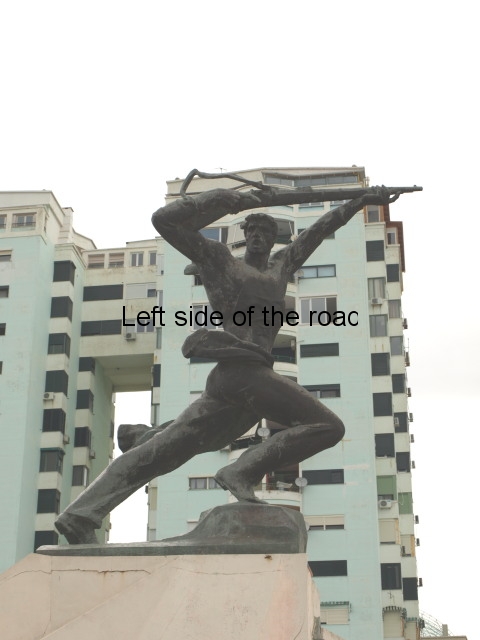

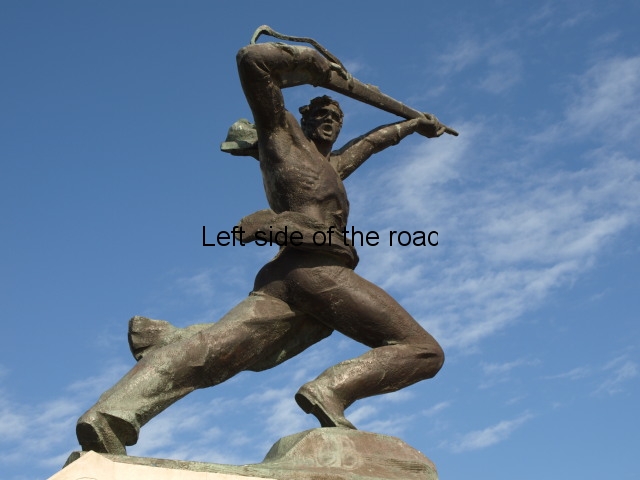

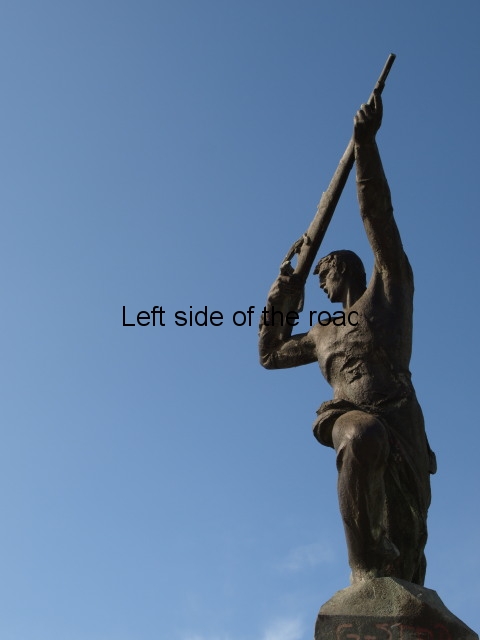

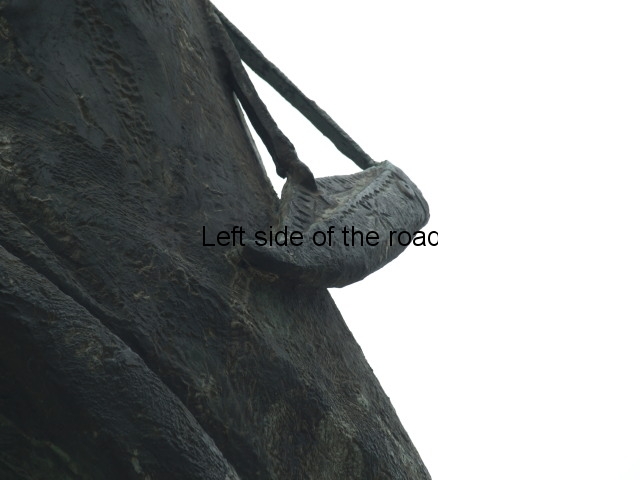

Bas Relief and Statue at Bajram Curri Museum

The early Albanian lapidars were relatively simple affairs, uncomplicated memorials to those who had died in the National Liberation War against Fascism and for Socialism. Come the Albanian ‘Cultural Revolution’ – starting in the late 1960s – the intention was to use such monuments in a much more educational manner as well as establishing a distinctive Albanian identity. This meant that artists who had been educated and trained under the Socialist regime were encouraged to depict events and memorials in a much more figurative manner. Examples of this approach are seen in the Musqheta monument in Berzhite and in the Peze War Memorial. As the Cultural Revolution moved into the 1980s a new approach developed. This was one where the monument told a story which had developed over time, showing a continuum of the struggle. This is seen, in a truly monumental manner on the Drashovice Arch (close to Vlora) and in the Albanians Mosaic on the façade of the National History Museum in Tirana but also on the more modest, at least in size, bas-relief and statue in the north-eastern town of Bajam Curri – although it also presents some new questions of the meaning of Socialist art.