Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery

More on Albania …..

Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery

Many of the Martyrs’ Cemeteries throughout Albania are situated on hills, sometimes quite high hills, in the vicinity of the cities and towns. This is the case with the Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery which, when it was constructed, would have been clearly seen from the centre of the town, the area around Sheshi Pavarësia (Independence Square) and the Bashkia (Town Hall). Up to the 1990s the buildings weren’t that tall but subsequent construction of high-rise flats has meant that you don’t really see the cemetery until you’re almost upon it.

As you come to the cemetery from the northern side a residential road brings you to a small, now abandoned, white building – all fittings having been removed. This is too small to have been a museum that were normally situated near a cemetery (and anyway, there’s a proper Historical Museum in the centre of town, in a good condition, looking as if it has only recently been refurbished and with many fine exhibits from the Socialist period). The building must have some connection to the cemetery (perhaps a place selling flowers on special occasions, but that’s only speculation) as it wouldn’t have served many other purposes.

From this building there are a series of steps taking you to the lapidar and statue at the highest point of the hill. The graves are laid out to the right of the steps, with the tombs on two levels. The whole area is relatively clean, the tombs are undamaged, and although the grass is growing between the stone tiles and a little untidy around the graves it is obviously cared for, at least on an occasional basis.

Probably when the cemetery was originally laid out there would just have been a lapidar, although not the one there now. If we go back to the late 1940s and early 50s the lapidar would have been a simple affair, sitting on the highest point, with a star somehow attached to the highest point facing the approach steps or perhaps surmounting the pillar.

The present lapidar sits on a large, raised plinth and must be, at least, the second reincarnation with the area being improved at the same time the statue was added. But what you see today is not what would have been seen at that time in the early seventies.

I’m almost certain the plinth and lapidar are from the 1970s but they have recently been restored following years of neglect and vandalism. The people and the Bashkia (local government) of Fier made a decision, anything up to ten years ago, to recover and recognise the past sacrifices of local people in the National Liberation War. It was in 2010 that the new (and awful) Liri Gero statue was unveiled and the monument to the 68 Girls was given a new plinth. It would make sense to think that the cemetery was restored at the same time.

The top face of the plinth is covered with marble tiles, is in a very good condition and are in three colours – red, white and brown – with a simple geometric pattern all the way around. The concrete below is unadorned, but clean and undamaged, and raises the plinth about a half a metre above the surrounding area.

The lapidar itself is a simple tall, rectangular pillar, wider at the bottom couple of metres or so, and then soaring vertically upwards. Whether the original marble facing was stolen or just fell off due to neglect I’m unsure. Now it is covered in white and greyish marble slabs from the top to the bottom. The highest limit of the widest part is indicated by a frieze of narrow, red tiles. However, there’s been a bit of cost cutting as the tiles on the topmost part of the lapidar are only on the side facing the steps and half way on the right and left face giving the impression that the decoration is ‘functional’, that is, on those parts most people will see as they come up the steps.

Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery

There’s also been a bit of cost cutting on the metal decoration on the main face. At the bottom there’s a large laurel branch with nine leaves. This looks to be treated sheet steel but there are signs of rust appearing at the joins of the leaves and the branch. Higher up the words ‘Lavdi Deshmoreve’ (‘Glory to the Martyrs) runs in large, golden letters vertically from the top down. From a distance this looks quite smart but once close up you can see that the letters have been made out of sheet steel, boxed, in three dimensions and then painted with gold paint. The elements are starting to take their toll and the paint is fading and rust is starting to show. At the top of the column, a few centimetres from the top, is a large, red, metal star – the symbol of Communism.

This is the first time, so far, that I’ve seen sheet steel used in the renovation of a lapidar. Whether the laurel branch would have been on the original I don’t know but the words ‘Lavdi Deshmoreve’ almost certainly would have, it’s universal on Albanian lapidars. But almost invariably the letters would have been made out of the more expensive bronze and it’s possible the originals had been looted and melted down for scrap.

The other component of the Fier Cemetery lapidar is a large (about twice life-size) statue of a female partisan. Being Fier, which still celebrates the bravery and heroism of Liri Gero and the 68 Partisan Girls, it’s not a surprise a female statue was chosen.

Fier Cemetery – Female Partisan

The figure stands on a solid block of concrete a couple of metres to the right of the monolith. Unusually, this statue has a name, ‘Liria fitohet dhe mbrohet me pushke’ meaning ‘Freedom won and defended by the rifle’. This is the implied meaning of most of the statues in such circumstances, taking its lead from a the revolutionary slogan of the Party of Labour of Albania, ‘To build Socialism holding a pickaxe in one hand and the rifle in the other’ – what has been gained by the workers is never guaranteed unless they are prepared to fight to defend them from all attacks, whether internal or external.

The statue is made of concrete and is the work of Gjergji J Toska and Qiraku Dano and was inaugurated in 1972 (or perhaps 1973). Toska was from the region of Myzeqeja, which is just to the north of Fier, between Divjake and Lushnje. In an interview he has said that where he grew up had an influence on his sculptural works. The sculpture took about 18 months to create and it was one of a number that had been commissioned for other cemeteries in the country. During the period when these type of sculptures were being installed in Albania it was normal for final approval to be granted by a local approval commission, in the early 1970s none such existed in Fier so photos of his work were sent to Tirana, where the work was well received.

Again there are elements that appear as a recurring motif. The woman is striding out as if she were climbing in the mountains, representing Albania and the fact that the Partisans used the hills as their base to attack the invaders and soon controlling the countryside, leaving the occupation forces surrounded in the towns.

In her right hand she holds the top of the barrel of her rifle, the butt of which is resting on the hillside next to her right foot. Although her weapon is a good representation of a bolt-action rifle it is much bigger than it would have been in reality. It would have taken, indeed, a true Amazon to fire such a weapon. But a weapon of such a size was necessary to allow the pose the sculptors have chosen to represent.

Her legs are as far apart as possible and she is stretching up to hold the top of the gun. Her left hand is stretched out behind, and above, her head to hold the right, top edge of partisan flag (and later to be the national flag of the country) with its symbol of the double-headed eagle with the Communist star above the heads. The top left corner of the flag is being held taut by having a fixed bayonet used as a short and temporary flagpole and the material is scrunched up in her hand so we don’t see the normal rectangle of the banner but more of a trapezoidal shape. The bottom right of the flag hangs down and partially covers her long hair, resting on her shoulder, a small triangle fluttering free. She has a determined look on her face and looks into the distance, to the left of her rifle.

Her limbs almost form an X, the right arm and left leg in a straight line, the other two limbs not doing so as her right leg is higher up the hill she is climbing. This gives the figure a sense of dynamism. She is moving forward as well as going up, going higher. Stretching she is pushing herself to achieve more. As a Partisan this is first and foremost victory in the National Liberation War against Fascism but in that war Communists were fighting to rid their country of the invaders but also in order to build a new society. And once the revolution is won it’s not possible to rest on your laurels. It’s difficult to make a revolution but it’s even more difficult to build a new sort of society – which will be constantly under attack from the capitalists, both in the country and from without, and more the powerful imperialist nations. So the task of a Partisan changes after liberation but it doesn’t get any easier – hence the title of the statue.

The Partisan is dressed in full uniform and has the red star on her cap and (what would have been) a red bandana around her neck. Around her waist she wears an ammunition belt.

Although it’s not immediately obvious from the front on looking at the back of the statue we see that her long hair is being blown over her left shoulder, indicating that a strong wind is blowing into her face. Another indication of being in the high mountains and suggests more movement as the flag would be fluttering.

Freedom won and defended by the rifle

The statue looks to be in very good condition and has recently been painted, the paint showing few signs of wear but then I don’t think that Fier gets particularly harsh weather conditions at any time of year. As with most of these concrete statues they would not have been originally painted at all, just the unadorned concrete, but this is a general approach to the cleaning and renovation of monuments now in different parts of the country.

The grave of Liri Gero will be in this cemetery, but I was amiss on my last visit and didn’t identify exactly where it is. I will remedy that on my next visit.

Fier Martyrs’ Wall of Honour

In some of the Martyrs’ cemeteries there’s a list of all those from the area who died in the war. However, this is not the case in Fier. On the first floor (which documents the period from pre-war years to 1990) of the Fier Historical Museum there’s a wall of remembrance, listing those from the Fier district who gave their lives for National Liberation. Although a recent creation it has all the aspects you’d expect from the Socialist period. The background is the Communist red and in the centre there’s a large black, double-headed eagle. Over the two heads is a golden star. At the very top are the words ‘Deshmoret e luftes antifashiste nacionalçlirimtare’ (Martyrs of the National Liberation War) in gold letters. And then, also in gold letters, are the names of 443 men and women from the Fier district – many more than are commemorated with a tomb in the cemetery.

Location of the Fier Martyrs’ Cemetery.

It’s best to arrive at the cemetery from the north, going up Rruga Skender Muskaj, from Rruga Jani Bakalli, and taking the first left along Rruga Koli Stamo – this brings you to the derelict building at the bottom of the steps.

GPS:

40.719541

19.56362402

DMS:

40° 43′ 10.3476” N

19° 33′ 49.0465” E

Altitude:

36.4m

Other lapidars in Fier.

So far I have been concentrating on the more elaborate monuments that come under the heading of ‘lapidars’ and which have been identified by the Albanian Lapidar Survey. To me that makes sense as the more ornate and complicated works of art have a story to tell and, although sometimes it has been difficult to find the information, it has been a pleasure trying to unravel what is before us. However, the vast majority of lapidars are more modest, but in their own way as important and significant a part of Albania’s history as the grand works of sculpture. More importantly all these small lapidars commemorate men or women who died fighting Fascism. Sometimes only two or three but even though they may not have been honoured as ‘Heroes of the People’ they were fundamental in the victory of November 1944.

In a sense the condition and evolution of the three other lapidars in the centre of Fier encapsulate the problem that Albania has in dealing with its past. Revolutionary Socialism never has been, and never will be, a State of all the people. For many reasons, class background, ideological and religious convictions, simple greed and selfishness there will always be those who will resist and use every opportunity to sabotage or undermine any achievements in a Socialist society. To all these negative factors have to be added the mistakes that the revolutionaries make, either out of ignorance, excessive zeal or even those who have infiltrated the Party in order to undermine its work, that exacerbate an already difficult task. And that’s before you have to take into account efforts by economically more powerful external forces to destroy a socialist society by whatever means possible.

This means that symbols of a past period are bound to be targets once the revolution loses support amongst a significant proportion of the population. In Albania the easiest target was the General Secretary of the Party of Labour for the majority of the time of Socialist construction, Enver Hoxha. As do all revolutionary Marxist-Leninists he believed in the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, a concept that developed from the concrete experience of workers in different parts of Europe seeking to build a society which was not based on exploitation and oppression. By presenting and arguing this ideological stance Hoxha was branded ‘Dictator’ by his enemies and detractors. It was to their advantage to try to make the concept, that has to involve the vast majority of a society to be successful, into a personal, individual matter.

But the idea of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ developed from the defeats that workers had undergone throughout history but especially from the late 19th century onwards. The thirty thousand men, women and children who were slaughtered in the last week of May 1871 at the end of the Paris Commune; the massacre of the Spartacists in Germany in 1919; the Civil War in Russia when the White forces were supported by 14 countries which only a few months before were sworn enemies; the interventions that Albania itself was subject to in the first years after liberation by the combined efforts of the British and the Americans all reinforced the truth that if the workers want to take real, and not just imagined, power (as is promised by Social Democracy and the ballot box) then they have to fight as much after the revolution as before it.

When we come back to the idea of the lapidars in Albania we see that Hoxha therefore become the easiest target. Public statues of him and the likes of the Memorial to the Berat Meeting of 1944, where he is a prominent figure amongst the fine sculpture where many tens of people were depicted (a sad loss), were destroyed in the early days of the counter-revolution. Now he is printed on mugs and pens in the souvenir shops of Gjirokaster or found as a small stone bust in small Albanian produce shops throughout the country – although a large bust of him is presently covered in a white tarpaulin in the ‘Sculpture Park’ behind the National Art Gallery in Tirana (or at least was in May of 2015).

The issue then becomes what to do with the other monuments, in the main commemorating those who died in the Anti-Fascist National Liberation War, in a country with such a small population that virtually every family would have had a relative amongst the country’s martyrs, within a generation or two. This meant that the majority of the monuments weren’t conscious targets of attack by reactionary forces but time, mindless and infantile vandalism and general neglect would play their part in erasing the country’s past.

There are a lot of questions which address this issue of identity, relationship to the past and how culture in general is seen in Albania today but that will take some space so I’ll return to that at a later date (or else this post will never end).

However, a part of that debate can be seen played out in the Fier lapidars.

Monument to the Three Martyrs

3 Martyrs – Fier

On the right hand side of the road, about 200m from Sheshi Europa Plaza (on the Fier ring-road) on the SH73 – the road to Berat – is a modest monument to three young men killed in the fight to liberate the city from the German Nazis. This is more typical of the lapidars around the country than those I have documented so far and if you didn’t know it was there it would be very easy to miss. Unlike War Memorials in the UK it is not common for there to be some sort of railing around the monument, not now nor in the past.

More typical but also on the modest side of typical. Some of the lapidars seek to impress as they soar skywards, although there may not be a great deal of ornament or decoration, but this one is minimalist and only stands about 2 metres high. So we have a simple, concrete monolith and on each side of that column there are two ‘wings’ which extend to just below half way up. It’s painted white (and fairly recently going by the condition) and the only other aspect of it is a marble plaque fixed to the top half of the facade. In most of these cases there would have been a red star but I could see no indication that something had been fixed just above the plaque (where you would expect to find one) so it’s possible that one was attached at the very top, normally a painted iron star attached by short, narrow pieces of reinforced iron. Whatever the situation in the past there’s no star there now.

Although it has been repainted there has been no attention paid to the plaque. The letters on the plaque had been cut out of the marble and then made more obvious by being painted in black. That has worn and it’s now very difficult to make out the words, especially if you aren’t good at the language and can’t make assumptions of what the words should be. In different places I’ve seen fairly badly delineated letters, perhaps more good intentions than skill, so this is something that has to be taken as it comes.

The most important point I wish to make about this lapidar is the fact that, to all intents and purposes, to most Albanians it doesn’t seem to exist. Obviously it exists as an entity but not for what it represents. On the day I visited this lapidar the area immediately around it was relatively clear. It sits at the side of a field where there is a small lay-by. When the ALS team visited it was holding up a moped and breeze blocks for some construction project were being stored right beside it.

3 Martyrs – Fier – photo by Marco Mazzi

Now, was this done consciously – that the people who were treating a war memorial as just a convenient post against which to lean their bike and therefore making apolitical statement – or unconsciously, not realising what it was and the bike and the breeze blocks had to go somewhere? Or are these small and unobtrusive lapidars just victims of their own simplicity, people don’t see them unless they really look?

Carved into the marble plaque are the words:

Më 27-VII-1944 ranë në luftën për çlirimin e qytetit të Fierit dëshmorët e Luftës Nacional Çlirimtare Tomor Dizdari, Orman Zaloshnja, Vangjel Gjini.

This translates as:

On 27-VII-1944, in the fight to liberate the city of Fier during the National Liberation War, the martyrs Tomor Dizdar, Orman Zaloshnja, Gender Vangeli fell.

At that time this area would have been considered well out of the town centre so, this is presumably the location where they actually died. So far I’ve been unable to find any more information about the three martyrs.

Location:

GPS:

40.71874003

19.56974097

DMS:

40° 43′ 7.4641” N

19° 34′ 11.0675” E

Monument to the 11th Brigade

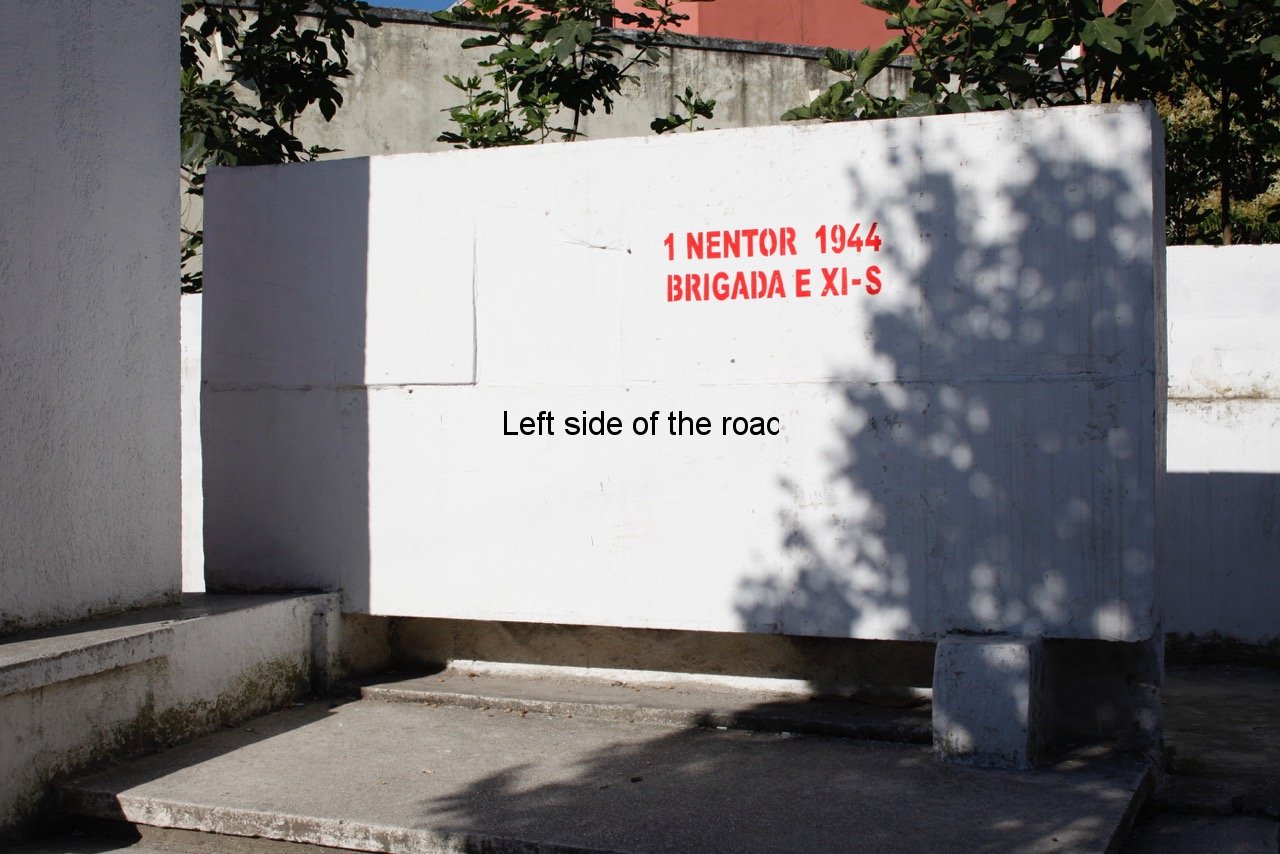

11th Brigade – Fier

This monument is right in the centre of town, not far from the Bashkia and at the junction of the street in which the Historical Museum can be found. This is a step up from the previous lapidar, displaying more architectural elements but without involving any sculptural elements. This particular lapidar also demonstrates the process, stated long ago and now again becoming a trend in parts of the country, of updating/upgrading/restoring/renovating the lapidars. Here the old has been demolished and a new created in the same location – and it’s almost a replica. But not quite.

Both consist of a platform, which has three steps on the right hand side of the long edge which continue on the right hand narrow edge. On this platform a monolith rises up to a height of about eight. On the left hand side of this monolith there’s a curved buttress at the bottom. It’s here where there’s a slight difference between the old and the new. On the old this right hand structure is joined by another rectangular slab of concrete which extends upwards about a metre over the first. On the new there is a space between these two components and the concrete in between is painted a deep red, which continues from under the curved buttress. On both the versions a concrete slab about 2 x 4 metres is placed at 90º to the lapidar.

Although there’s a possibility that the old has been renovated I don’t think this is possible, at least not for all of the structure. The platform has been faced on the lower part by false brick tiles, as have the steps. The top of the platform has also been covered with marble tiles. This would cover all the wear and tear of over 40 years on the concrete so that part might be part of the original. I don’t think this is the case with the rest of the lapidar.

11th Brigade – Fier – photos by Marco Mazzi

Apart from the separation of the two slabs of concrete it all looks a lot smarter, the edges are sharper and I don’t think that can be achieved with a repair job (and would you put new, modern concrete on a crumbling forty-year old base? Also the slab that contains the letters appears wider than the original. Another difference is the red star on the facade that faces to the left. On the old this is larger and has greater depth whereas on the new it’s smaller and flatter.

The wording on the two versions is also slightly different. On the old the letters are just stencilled, in red paint, onto a white background – these were probably not the original but a later ‘restoration’. They are:

1 Nentor 1944 Brigada E XI-S

This translates to:

1 November 1944 S Brigade XI

S is for Sulmuese. This can be translated as assault, shock or guerrilla group. Units of the Albanian Partisan Army were not designed for mass, set battles. They could move fast and therefore weren’t as heavily armed as the Fascist opposition which ultimately secured them victory. It is one of those contradictions of war that the better equipped force can actually find that what appears an advantage on paper, in crucial circumstances, becomes a hindrance and bogs them down in a way that makes them vulnerable. The E? This is a grammatical device which seems somewhat redundant.

There are indications that there might have been more text or an image of some kind (on the edge close to the column) but there’s no way to work out what might have been.

The letters are almost the same, but not exactly, on the new. They are inlaid on a large rectangle of marble (a much more sophisticated presentation than the previous version) and read:

1 Nentor 1944 U formua brigada XI Sulmuese

This translates as:

1 November 1944 – the XIth Assault Brigade was formed

This is confusing to me. I believe that the 1st November 1944 is the date when Fier was liberated from the Nazis. The 11th Brigade would have been formed long before that as the whole of the country was liberated on 29th November of that year.

Location:

GPS:

40.72572702

19.55575199

DMS:

40° 43′ 32.6173” N

19° 33′ 20.7072” E

Monument to Petro Sota and the 1943 Nazi Massacre

Petro Sota and 1943 Massacre – Fier

The third lapidar in Fier is different again. It’s a simple monolith, which is made grander by being placed on a plinth, and is in the public park in the centre of the town. On the side facing the centre of the park there’s a marble plaque with an inscription. The park is now considerably smaller than it would have been when the lapidar was first installed as a huge chunk of it has been taken up by a large mosque. Considering that all the other lapidars in the town have been cleaned recently this one is showing signs of wear, although structurally sound, and the inscription – black paint in the carved marble – is showing signs of wear it’s still quite easy to read the words.

What makes this lapidar unusual is that it actually commemorates a person and an event. So far I haven’t come across monuments where the space is shared.

The first is recognition of another of Fier’s sons in the National Liberation War, Petro Sota. He became a Communist before the Italian Fascists invaded the country in 1939 and once the town was occupied he worked as a courier of information, news and materials for the liberation cause. He was a driver and had a certain amount of freedom to move around and with different ruses got around the roadblocks and checkpoints the Fascists imposed or order to maintain control of the town.

On one occasion he used a child sized coffin to bring in the Party newspaper and on another caused the Italian soldiers to follow him, allowing free passage for those who were bringing in contraband. He is remembered as when, in July 1943, things went wrong on a mission he was able to destroy sensitive Resistance material before being killed.

He is recognised in the top half of the inscription:

Petro Sota, vrarë më 13 korrik 1943 nga fashistët italianë duke kryer detyrën e ngarkuar nga njësiti gueril.

Which translates as:

Petro Sota, killed on 13 July 1943 by the Italian Fascists, carrying out tasks entrusted to him by the guerrilla unit.

The second half of the inscription asks more questions than it answers. This is:

Po këtu më 10 shtator 1943 nazistët gjermanë masakruan 45 qytetarë të pafajshëm

In English:

But here on September 10, 1943 the German Nazis massacred 45 innocent civilians

So far I don’t have the information that explains exactly what happened and why. This was just after the Nazis replaced the Italian Fascists, who had by this time effectively withdrawn from the war on all fronts. It’s possible the Germans wanted to stamp their mark on the country, knowing already the sort of fierce opposition they would face from the Communist Partisans. Also, exactly at this time the German forces were being defeated outside the village of Drashovice (in the Selenice valley close to Vlora) so it could have been a massacre caused by the Nazis’ frustration.

Whatever the reason 45 is a lot of people at one time and what surprises me the most is there wasn’t a more substantial monument to the event, as there is in Borovë and Uznovë. The names are not even listed, the event only meriting a couple of lines on a very modest memorial – and shared at that. Something to investigate.

The tally of Nazi five atrocities, in effect war crimes, in Albania that I have identified, so far, make the decision to establish a memorial to the German dead during their invasion of the country even more of a mystery, apart from establishing the fascist credentials (or at least forelock-tugging attitude) of past, post-1990 governments in Albania.

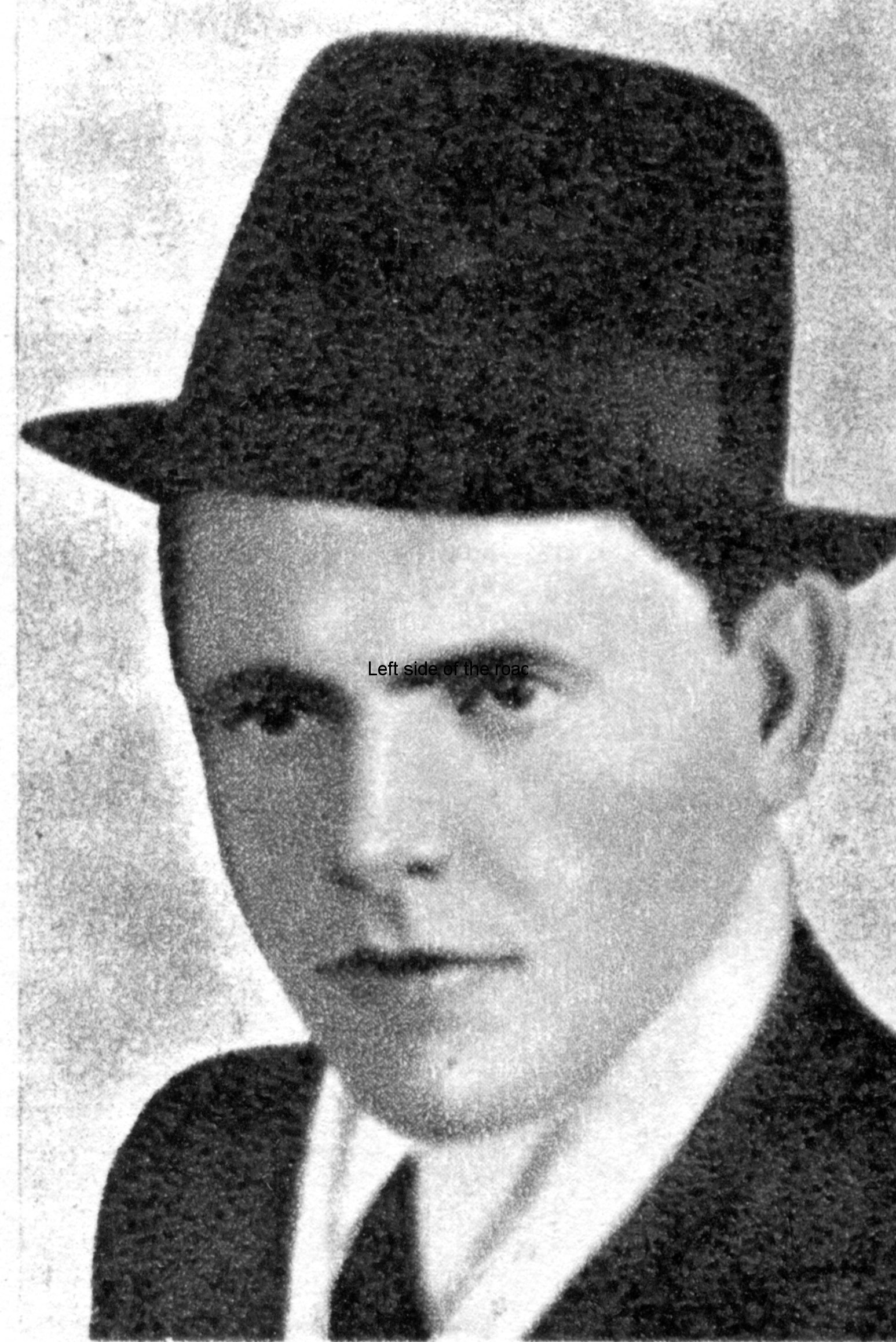

Petro Sota

The reason for the lack of a memorial to those 45 people becomes even more confounding when we look at a statue of Petro Sota that was unveiled in 2014. I have the utmost respect for what Petro might have done during the Liberation War and I have no problem with the placing a bust of him in the town of his birth – but aren’t we forgetting priorities here? Another question for which there is, as yet, no answer.

This new stature is the work of Fatos Shuli (a sculptor I have not come across before and about who I know nothing) seems to capture the individual that was Petro Sota. His picture in Flasin Heronj të Luftës Nacional Çlirimtare (Heroes of the National Liberation War Speak for themselves) gives the impression that he was a dapper dresser before the serious work of ridding his country of the invaders got in the way. This idea of style is captured in the new bust but, I must admit, I question the priorities of the Fier Bashkia.

Location:

GPS:

40.72619397

19.55685496

DMS:

40° 43′ 34.2983” N

19° 33′ 24.6779” E

More on Albania …….