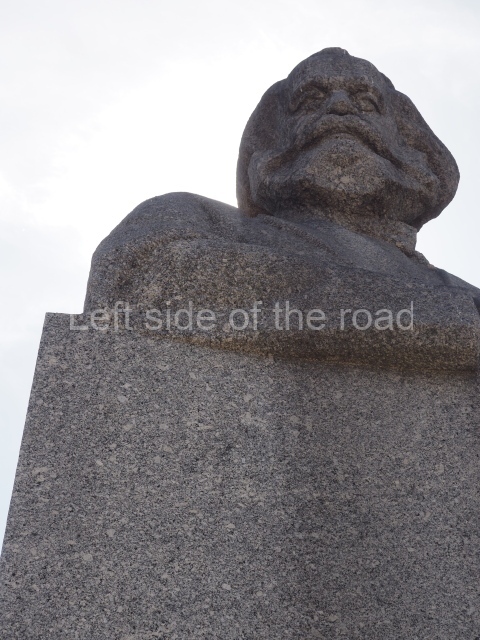

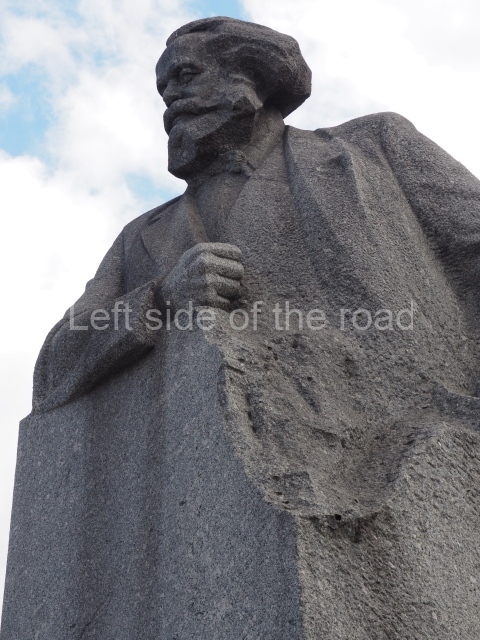

- Karl Marx – circa 1850

The Great ‘Marxist-Leninist’ Theoreticians

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Collected Works

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels – Writings, compilations and analyses

Frederick Engels – pamphlets, books and commentaries

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told

Karl Marx – pamphlets, books and commentaries

Virtually everything that has been published by Karl Marx is included in the 50 volume Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.

However, his contribution to the world revolutionary movement has meant that many of his most significant works have been produced as individual pamphlets/books. The intention is to post as many of those as possible on this page.

Those works that he produced in collaboration with his close comrade-in-arms, Frederick Engels are also available here.

Selected Works

Karl Marx, Selected Works in two volumes, Volume 1, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1947, 447 pages.

Karl Marx, Selected Works in two volumes, Volume 2, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1945, 694 pages.

Selected Works in One Volume, Progress, Moscow, 7th printing, 1986, 788 pages.

Selected Works in Three Volumes, Progress, Moscow,

Volume 1, 3rd printing, 1976, 596 pages.

Volume 2, 4th printing, 1977, 502 pages.

Volume 3, 3rd printing, 1976, 577 pages.

Selected Writings in sociology and social philosophy, edited by TB Bottomore and Maximilien Rubel, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964, 268 pages.

Selected Writings, 2nd edition, edited by David McLellan, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000, 687 pages.

Collected Works of Karl Marx, illustrated, Delphi Classics, Hastings, 2016, 3561 pages.

Capital

Capital, Volume 1, edited by Frederick Engels, William Glaisher, London, 1912, 816 pages.

Capital, Volume 1, a critical analysis of Capitalist Production, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1974, 767 pages.

Capital, Volume 2, the process of circulation of capital, original English language edition, 319 pages.

Capital, Volume 3, the process of capitalist production as a whole, original English language edition, 645 pages.

Theories of Surplus Value, (Volume IV of Capital), Part 1, Karl Marx, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1969, 506 pages.

Theories of Surplus Value, (Volume IV of Capital), Part 2, Karl Marx, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1968, 661 pages.

Theories of Surplus Value, (Volume IV of Capital), Part 3, Karl Marx, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1971, 637 pages.

Grundrisse, foundations of the critique of political economy (rough draft), written in 1857-1861, English translation by Martin Nicolaus, 862 pages.

Capital, Volume 2, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1986, 551 pages.

Capital, Volume 3, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1984, 948 pages.

Individual pamphlets and books

The Poverty of Philosophy, with an introduction by Frederick Engels, Martin Lawrence, London, ND, 1930s?, 214 pages.

The Civil War in France, with an introduction by Frederick Engels, Martin Lawrence, London, 1933, 92 pages.

The Class Struggles in France, 1848-50, Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers in the USSR, Moscow, 1934, 159 pages.

Value, Price and Profit, Allen and Unwin, London, 1935, 94 pages.

A Handbook of Marxism, with selections from the works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, International Publishers, New York, 1935, 1082 pages,

Wage, Labour and Capital, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1942, 48 pages.

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Allen and Unwin, London, 1943, 192 pages.

Critique of the Gotha Programme, Lawrence and Wishart, London, ND, late 1940s?, 110 pages.

Marx on China – 1853-1860, articles from the New York Daily Tribune, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1951, 98 pages.

The Paris Commune, New York Labor News Company, New York, 1954, 117 pages.

Notes on Indian history, 664-1858, FLPH, Moscow, 1960, 206 pages.

Wages, Price and Profit, FLP, Peking, 1965, 83 pages.

Pre-Capitalist Economic Formations, mostly being a section of the Grundrisse, circa 1857-1858 (as translated by Jack Cohen) and also of few letters by Marx, International Publishers, New York, 1965, 158 pages.

The Civil War in France, FLP, Peking, 1966, 287 pages.

The Communist Manifesto, with Frederick Engels, introduction by AJP Taylor, Pelican, London, 1967, 124 pages.

The Civil War in France, Progress, Moscow, 1968, 91 pages.

The class struggles in France 1848 to 1850, Progress, Moscow, 1968, 143 pages.

Genesis of Capital, Progress, Moscow, 1969, 70 pages.

Manifesto of the Communist Party, with Frederick Engels, FLP, Peking 1970, digital version by From Marx to Mao, 47 pages.

Karl Marx – Notebook on the Paris Commune, Press excerpts and notes, edited by Hal Draper, Independent Socialist Clippingbooks No. 8, Independent Socialist Press, Berkeley, 1971, 108 pages.

The Unknown Karl Marx, edited by Robert Payne, New York University Press, New York, 1971, 339 pages.

The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1972, 132 pages.

Critique of the Gotha Programme, FLP, Peking, 1972, 91 pages.

The Poverty of Philosophy, Progress, Moscow, 1973, 205 pages.

Preface and Introduction to ‘A contribution to the Critique of Political Economy’, FLP, Peking, 1976, 63 pages.

A contribution of the Critique of Political Economy, Progress, Moscow, 1977, 262 pages.

Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts, 1844, Progress, Moscow, 1977, 226 pages.

A contribution to the critique of political economy, Progress, Moscow/Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1981, 264 pages.

Herr Vogt, a spy in the Workers Movement, New Park, London, 1982, 336 pages.

Wage, Labour and Capital, lecture by Marx, 1847, as edited by Engels in 1891, 25 pages.

Value, Price and Profit, lecture by Marx, 1865, 32 pages.

Marx-Engels Correspondence, from the Marxist Internet Archive, 608 pages.

Wage-Labour and Capital and Value, Price, and Profit, International Publishers, New York, 2006, 110 pages.

The first writings of Karl Marx, edited by Paul M. Schafer, Ig Publishing, New York, 2006, 223 pages.

Dispatches for the New York Tribune – Selected Journalism of Karl Marx, selected by James Ledbetter, Penguin, London, 2007, 322 pages.

Manifesto of the Communist Party, with Friedrich Engels, International Publishers, New York, 2007, 48 pages.

The Communist Manifesto, with Frederick Engels, introduction by Yanis Varoufakis, Vintage, London, 2018, 63 pages.

Wage Labour, and Capital and Value, Price and Profit, Foreign Languages Press, Paris 2020, 128 pages.

Compilations with other great Marxists

Ten Classics of Marxism, Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, International Publishers, New York, 1940, 785 pages.

Marx, Engels and Lenin on the Irish Revolution, Ralph Fox, The Cork Workers Club, Cork, 1974, 36 pages.

Marx, Engels and Lenin – On the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1975, 41 pages.

Marx-Engels-Lenin, On Scientific Communism, FLPH, Moscow, 1967, 537 pages.

On Scientific Communism, Marx, Engels and Lenin, Progress, Moscow, 1976, 537 pages.

On Dialectical Materialism, Marx, Engels and Lenin, Progress, Moscow, 1977, 422 pages.

The Woman Question, Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, International Publishers, New York, 1977, 96 pages.

Marxism and the Liberation of Women, Quotations from Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, VI Lenin, Joseph Stalin and Mao Tse-tung, Union of Women for Liberation, London, n.d., mid-1970s?, 64 pages. Includes a statement of aims of the Union of Women for Liberation.

The Civil War in France: The Paris Commune, Karl Marx and VI Lenin, International Publishers, New York, 1988, 182 pages.

Biographies

Karl Marx, the story of his life, Franz Mehring, Covici Friede, New York, 1935, 608 pages.

Karl Marx, 1818-1883, for the anniversary of his death March 14, 1883, includes the speech given by Frederick Engels at Marx’s graveside, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1941, 29 pages.

Karl Marx, his life and work, reminiscences by Paul Lafargue and Wilhelm Liebknecht, International Publishers, New York, 1943, 64 pages.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, D Riazanov, International Publishers, New York, n.d., 1940s, 224 pages.

Karl Marx, a biography, Heinrich Gemkow, Verlag Zeit im Bild, Dresden, 1968, 427 pages.

Marx comes to India, earliest Indian biographies of Karl Marx by Lala Hardayal and Swadeshabhimani Ramakrishna Pillai, with critical Introduction, edited by PC Joshi and K Damodoran, Manohar Book Service, Delhi, 1975, 133 pages.

Karl Marx, a biography, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977, 694 pages.

Marx – Life and Works, Maximilien Rubel, MacMillan, London, 1980, 140 pages.

The daughters of Karl Marx, family correspondence, 1866-1898, Andre Deutsch, London, 1982, 342 pages.

Karl Marx, Beacon for Our Times, Gus Hall, International Publishers, New York, 1983, 94 pages.

Karl Marx and our time, articles and speeches by various revisionist leaders and commentators of the post-1956 Soviet Union, Progress, Moscow, 1983, 203 pages.

Karl Marx Remembered, 1893-1983, comments at the time of his death, edited by Philip Foner, Synthesis Publication, San Francisco, 1983, 304 pages.

Eleanor Marx, Family Life, 1855-1883, Volume 1, Yvonne Kapp, Virago, London, 1986, 319 pages.

Marx in London, an illustrated guide, Asa Briggs and John Callow, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 2008, 110 pages.

Analyses and Commentaries

Marx and the Trade Unions, A Lozovsky, International Publishers, New York, 1942, 188 pages.

Marx on Money, Suzanne de Brunhoff, Urizen Books, New York, 1973, 139 pages.

Karl Marx – Interviews and Recollections, edited by David McLellan, Macmillan, London, 1981, 186 pages.

Marx’s Theory of Commodity Surplus Value, Formalised exposition, KK Valtukh, Progress, Moscow, 1987, 360 pages.

How To Read Karl Marx, Ernst Fischer, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1996, 192 pages.

Rereading Capital, Ben Fine and Laurence Harris, Columbia University Press, New York, 1979, 184 pages.

Marx for Beginners, Rius, Pantheon Books, New York, 1976, 156 pages.

Karl Marx and World Literature, SS Prawer, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1978, 446 pages.

The Great ‘Marxist-Leninist’ Theoreticians

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Collected Works

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels – Writings, compilations and analyses

Frederick Engels – pamphlets, books and commentaries

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told