Memento Park, Budapest

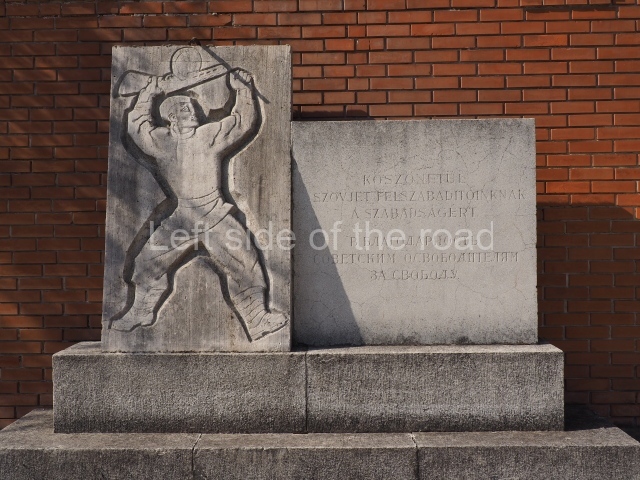

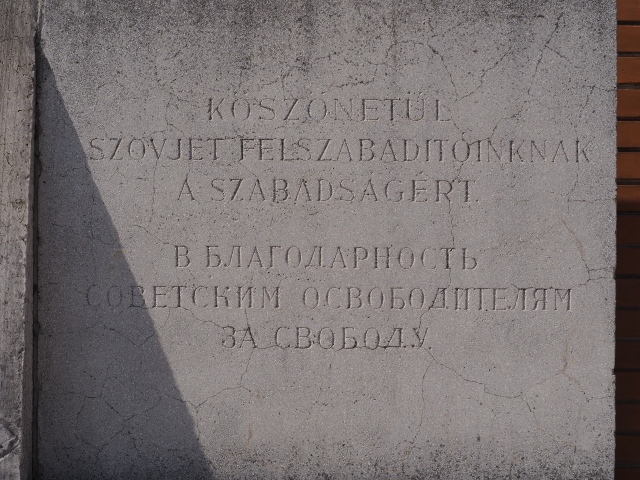

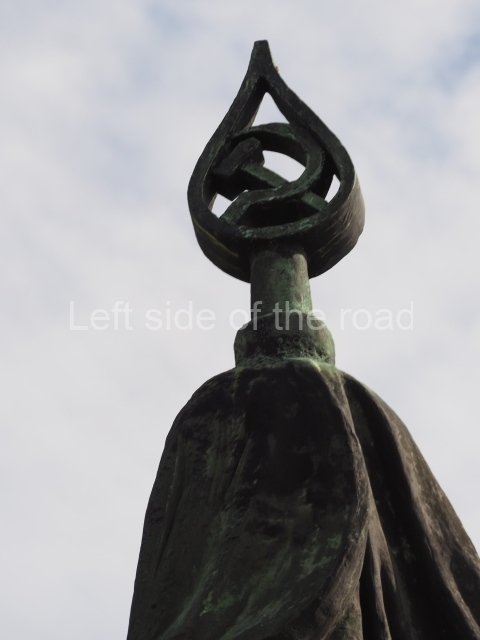

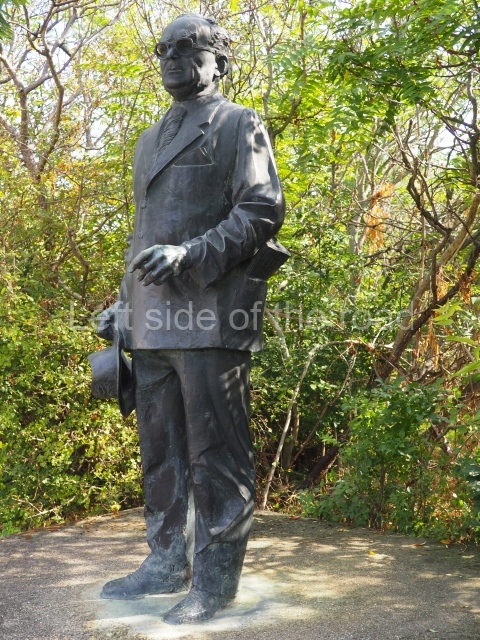

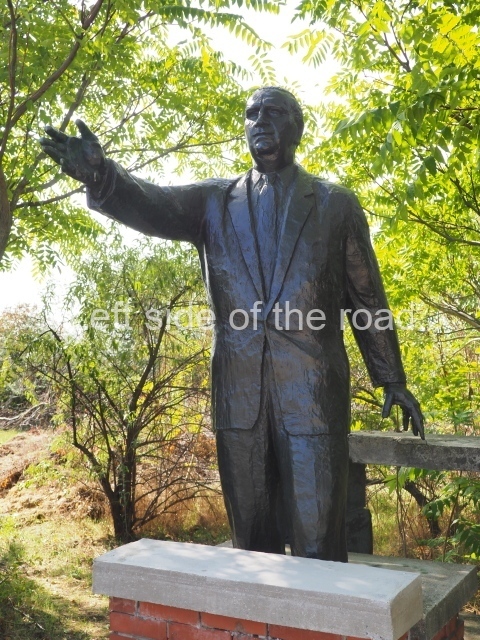

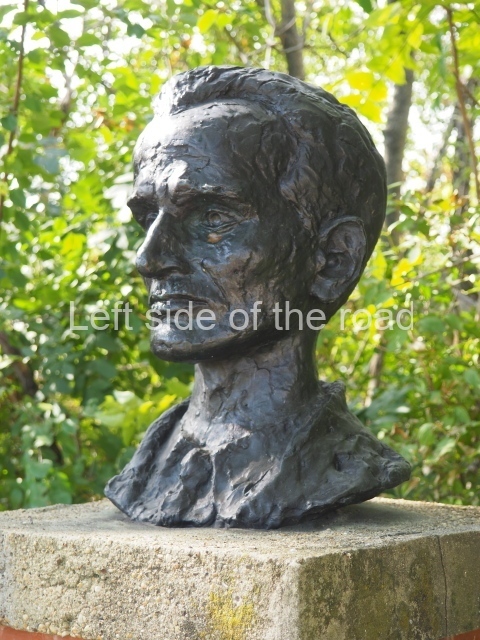

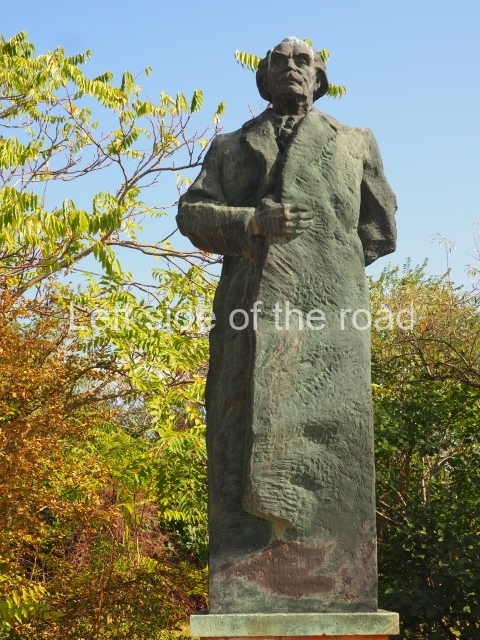

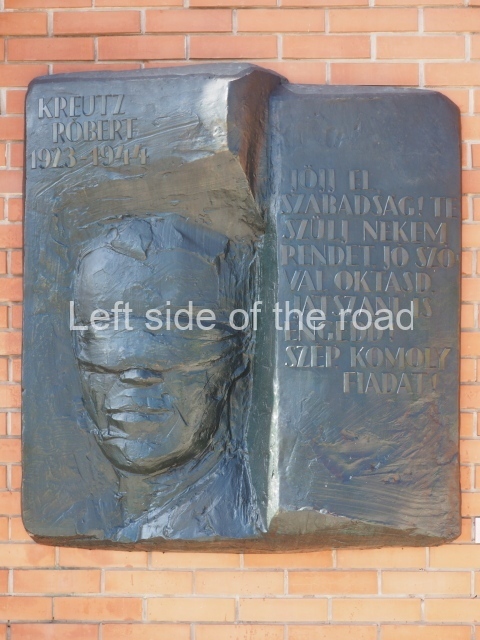

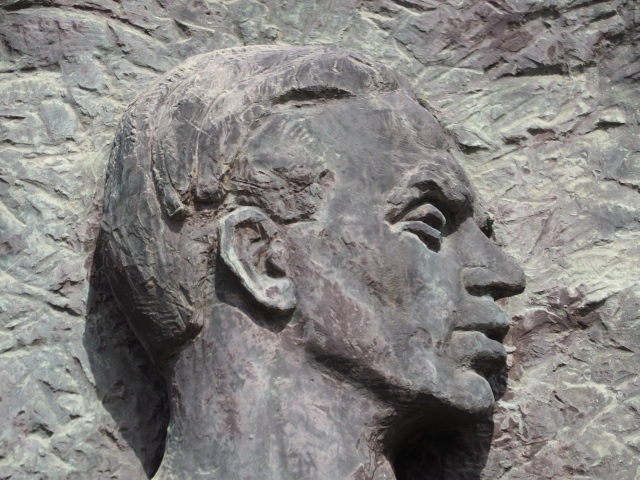

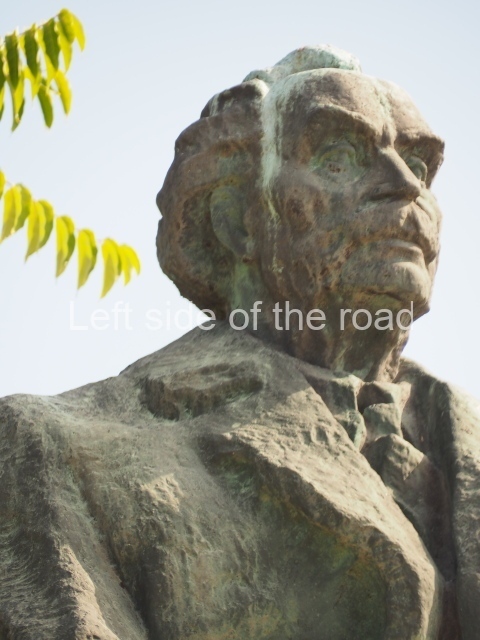

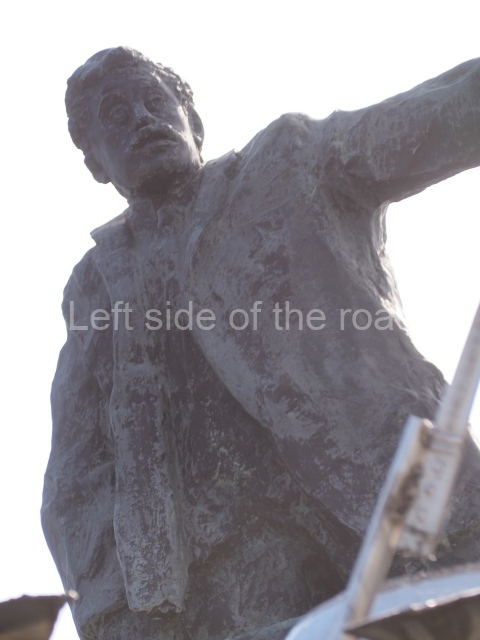

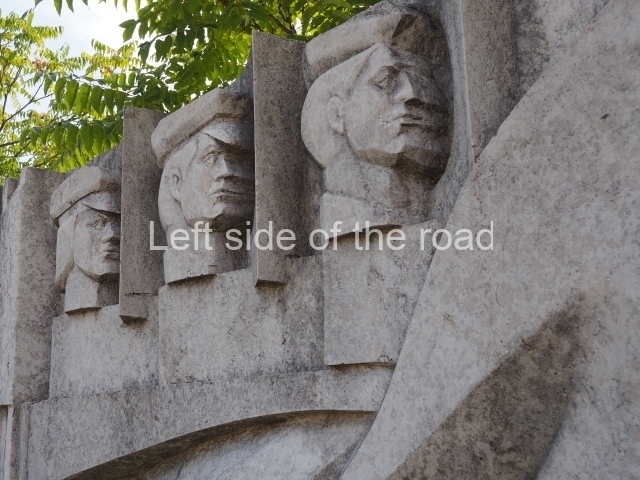

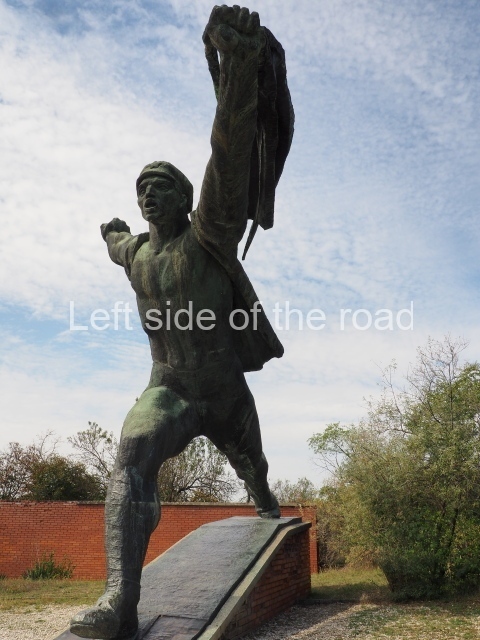

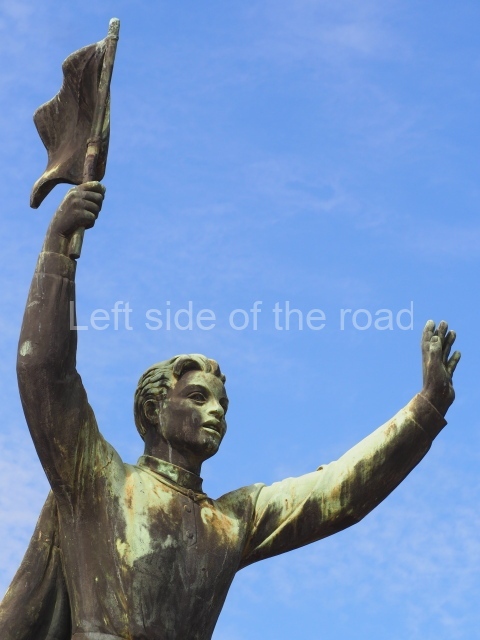

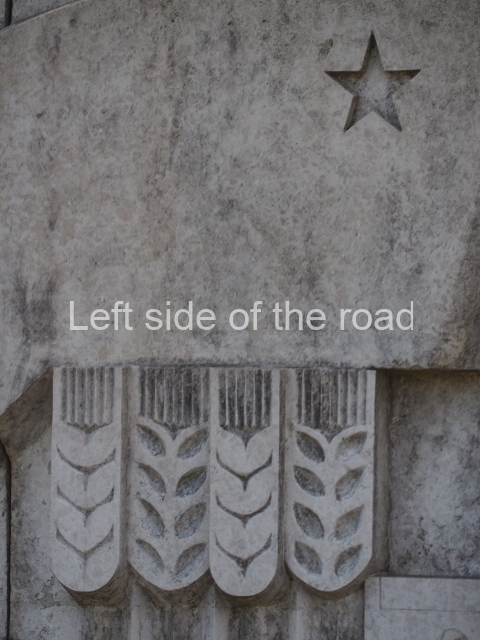

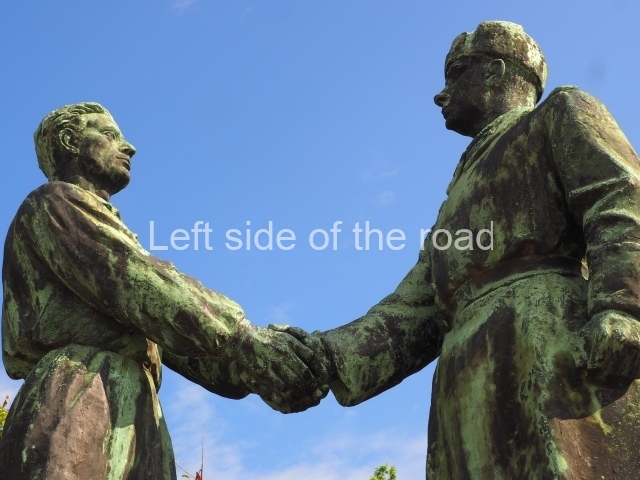

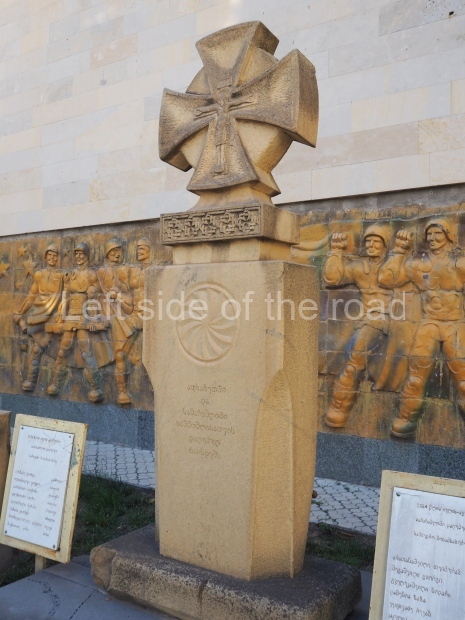

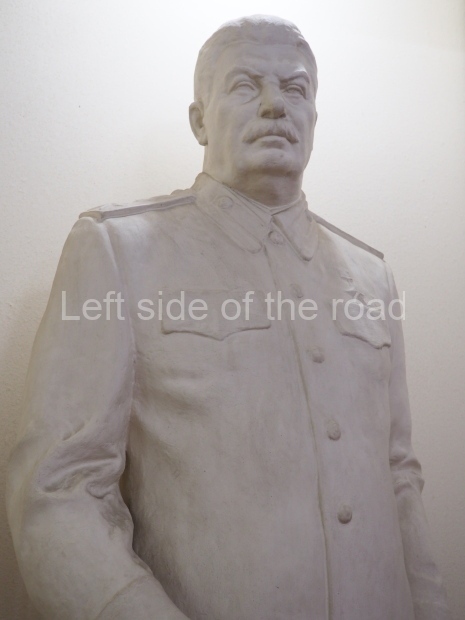

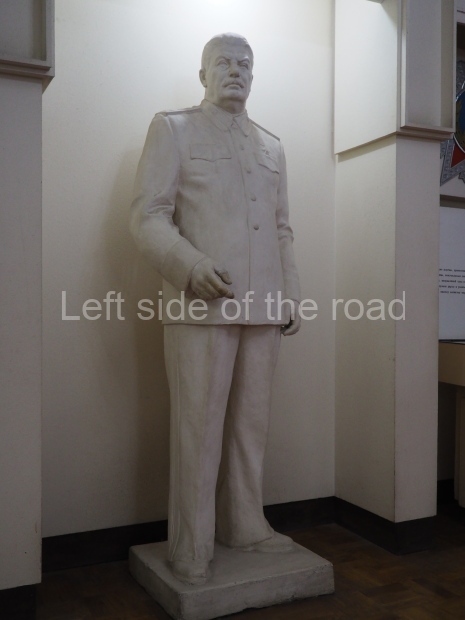

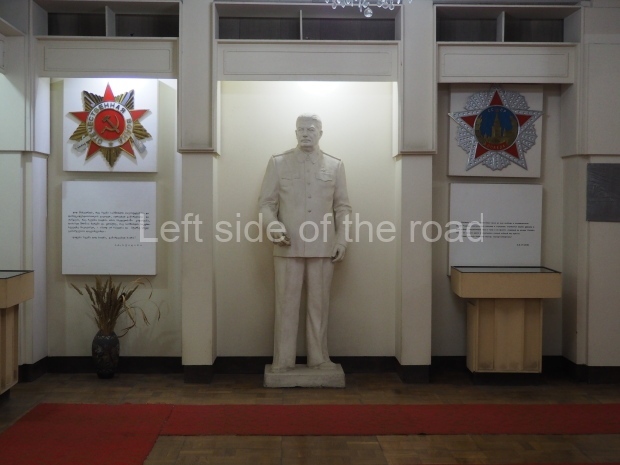

This is a collection of statues, bas reliefs and busts that used to be located in public spaces in the city of Budapest during the period of the countries Socialist construction. This is similar (but not an exact equivalent) of the Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park, Moscow, and the Museum of Socialist Art – Sofia, Bulgaria. It consists of 41 items, spread out over three sections, in the open air. The collection consists of what might be called the seminal works that were on display in the city but the curation also seems to have chosen some of the exhibits based upon the uniqueness of their design. Hungarian sculptors seemed to have followed a slightly different path in representing individuals and events from some of the other countries in Eastern Europe. Here you will see figures that are almost abstract, still ‘figurative’ but a shift away from the norm of the time.

What to look for;

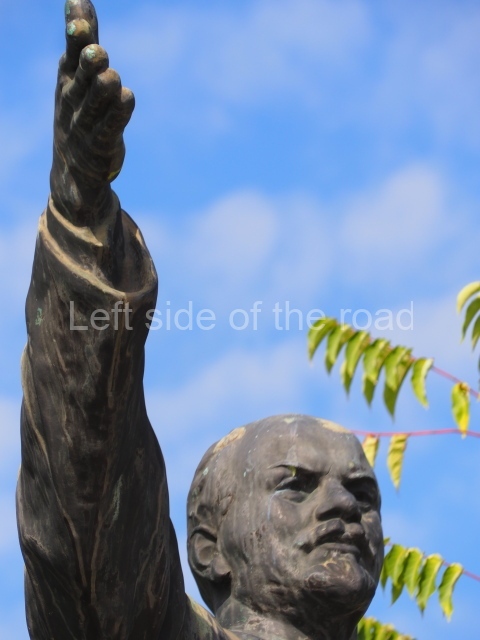

- a couple of good Lenins – although one of them looks slightly different from what we’re used to – and one of which Vladimir Ilyich holds his scrunched up cap in his left hand;

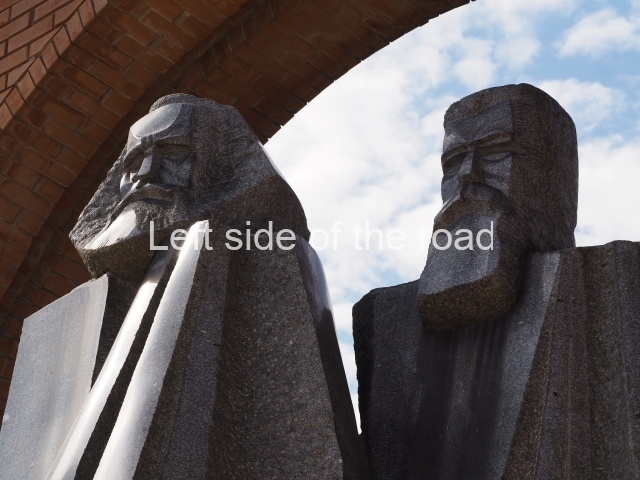

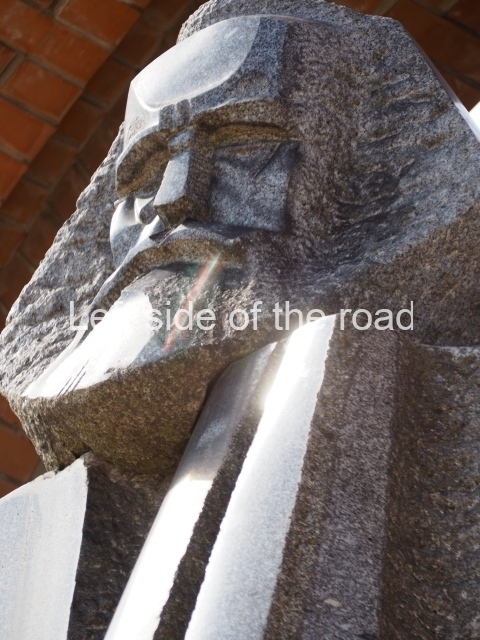

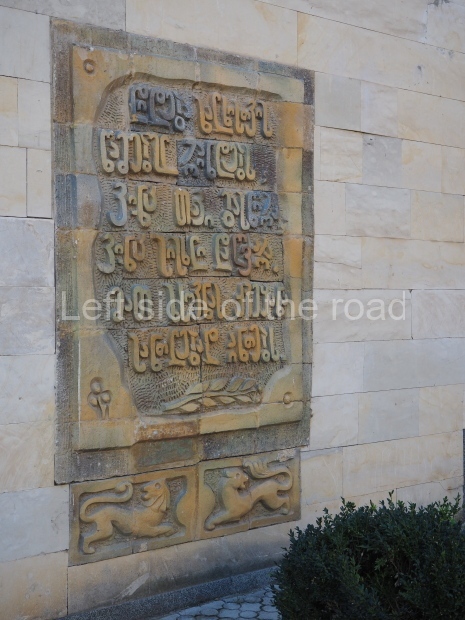

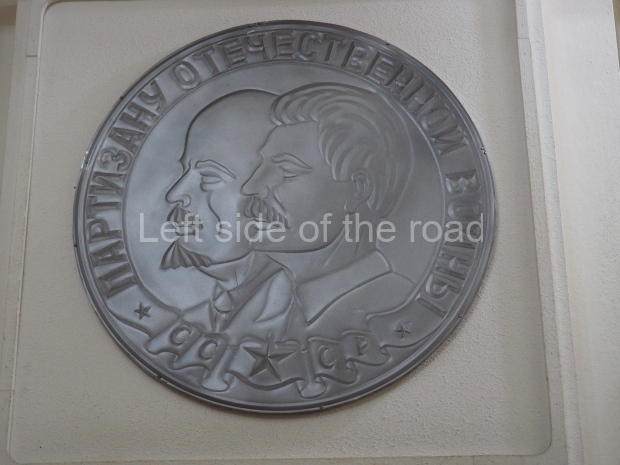

- an interesting, stylised, made of stone, ‘the only Cubist-style monument of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels in the world’ to the right of the main entrance;

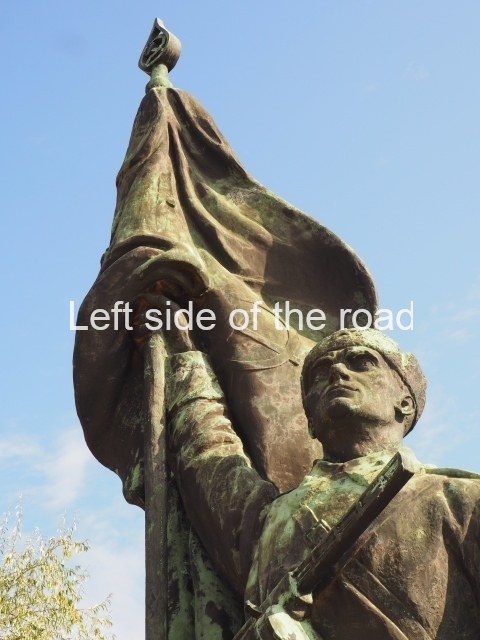

- a truly monumental statue of a Soviet Red Army man – who used to be placed at base of the memorial to Freedom in present day Liberty Square;

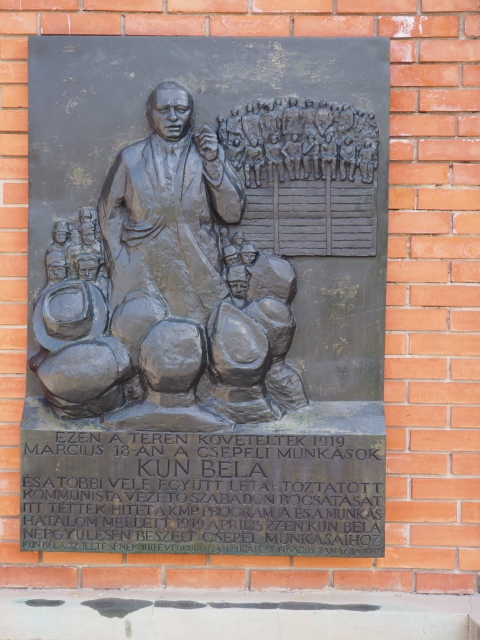

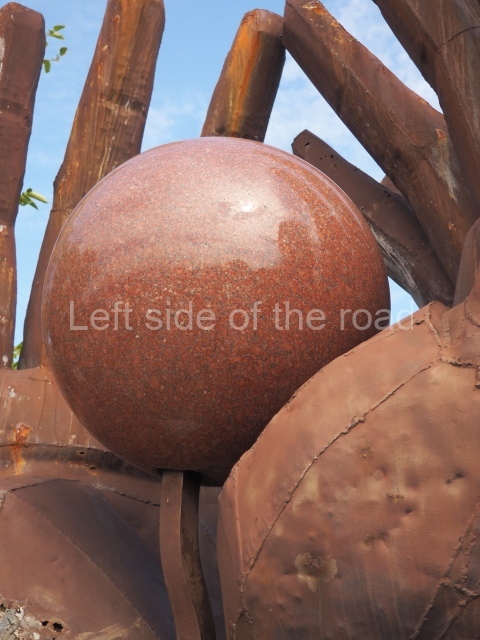

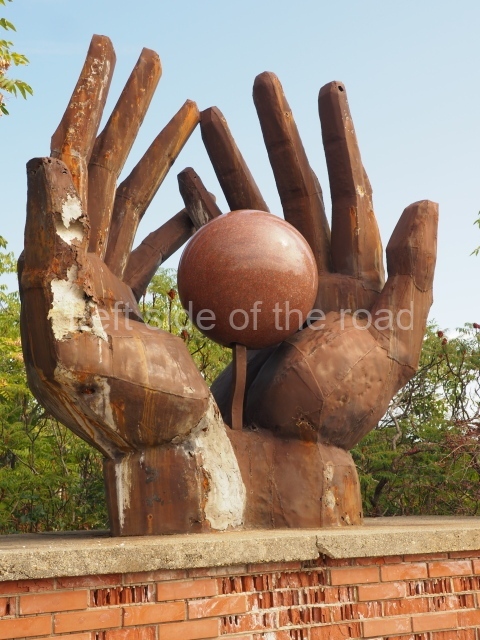

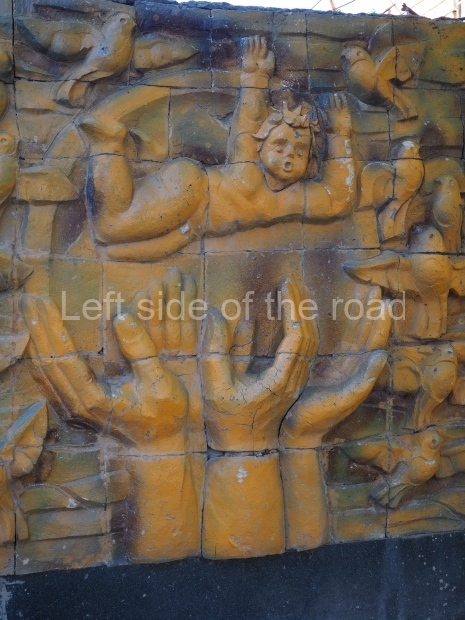

- the large statue group as a monument to Bela Kun and the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic, a late statue (1986) its composition is quite unique and seems to be open to a whole number of interpretations;

- a couple of monuments to Georgi Dimitrov, the Bulgarian leader of the Communist (Third) International;

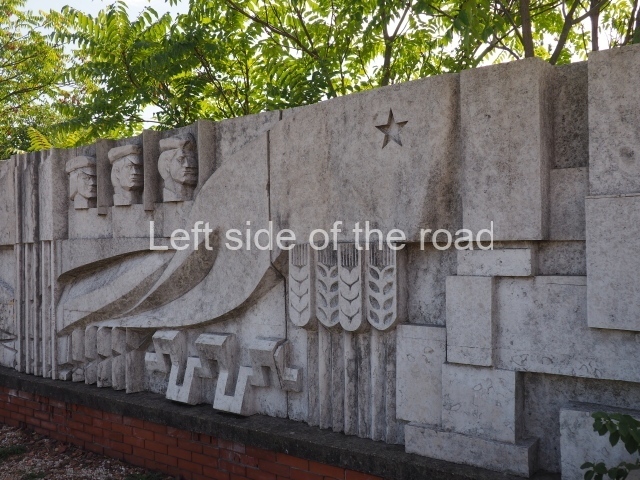

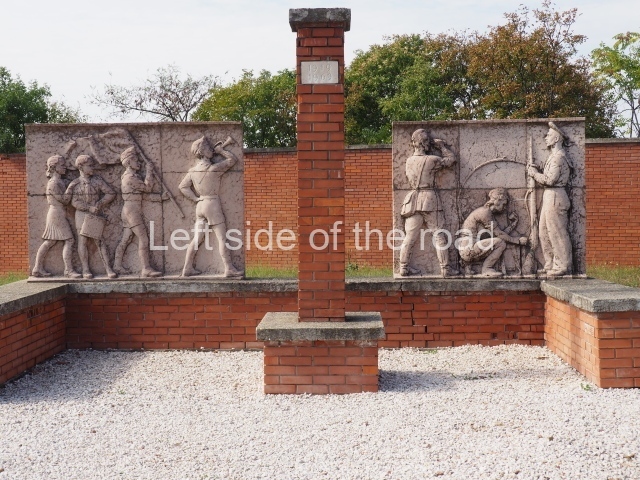

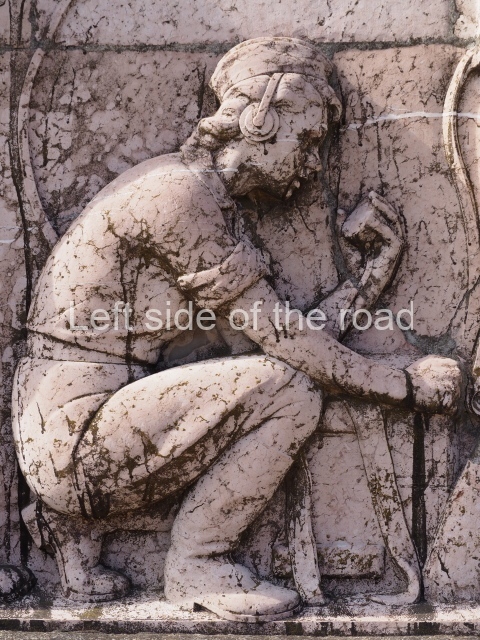

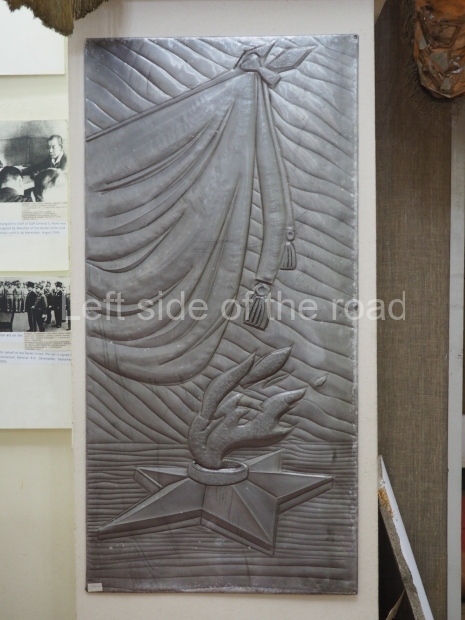

- the two bas relief panels that were originally planned to be part of the decoration of one of the Budapest metro system;

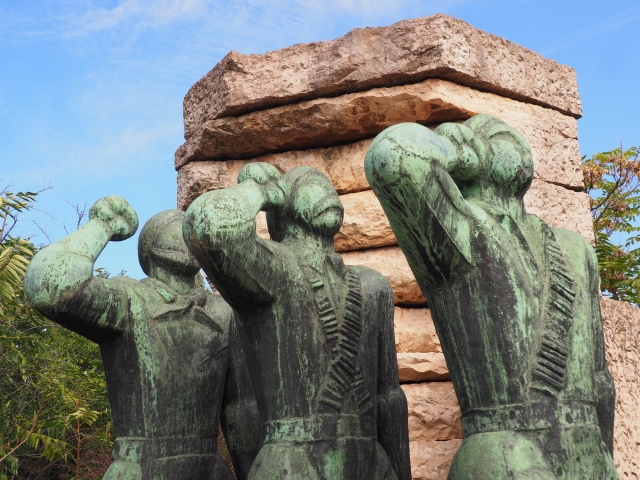

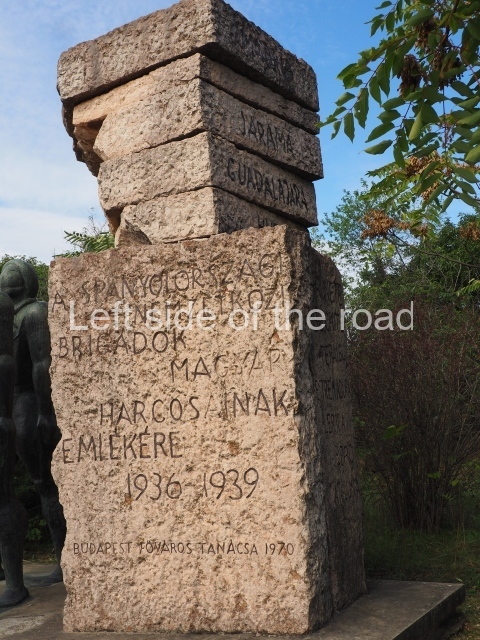

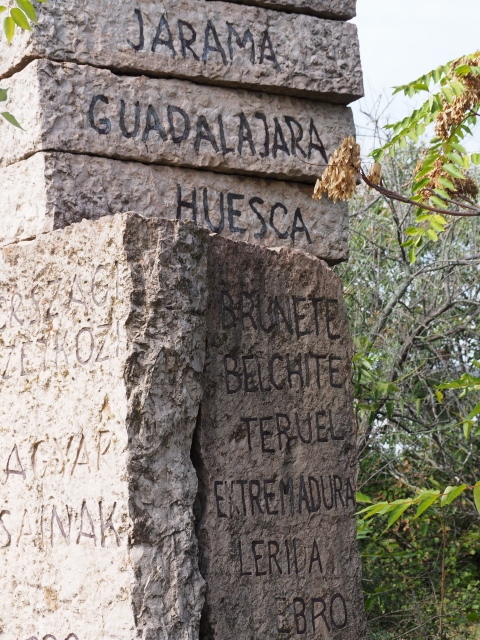

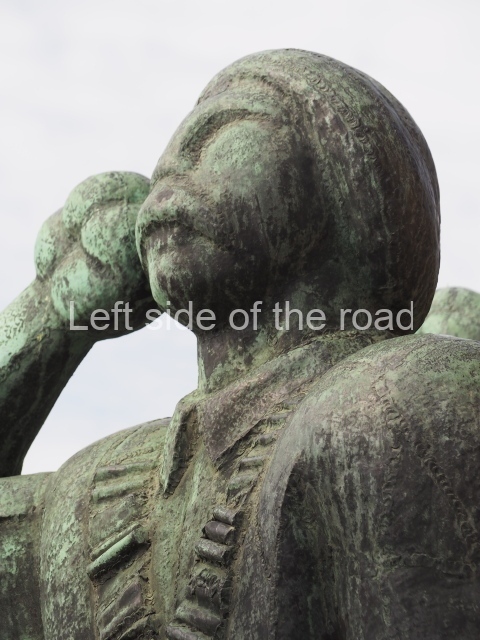

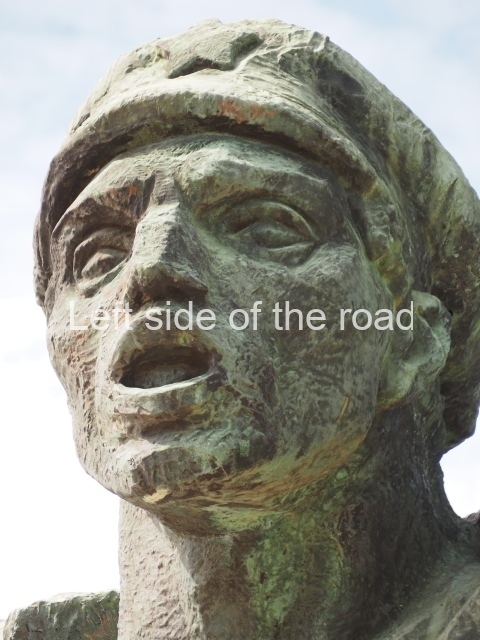

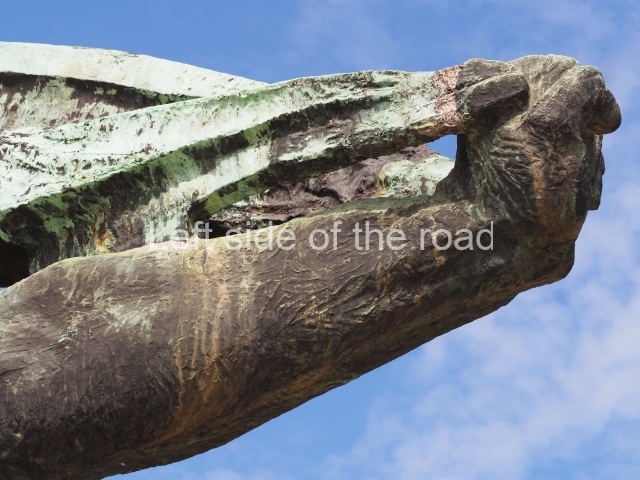

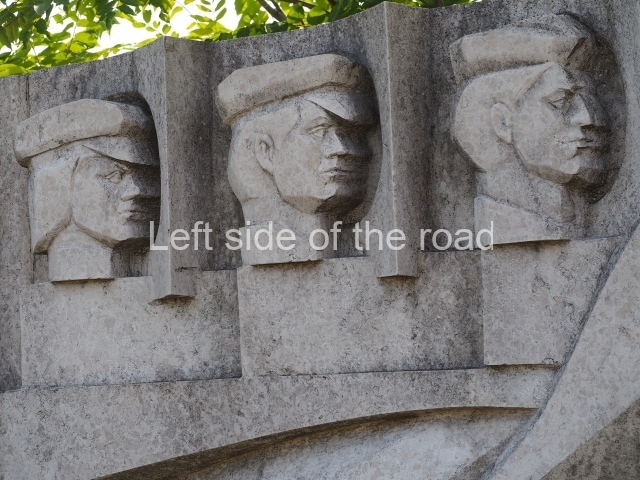

- the robotic forms of the three Hungarian volunteers of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War;

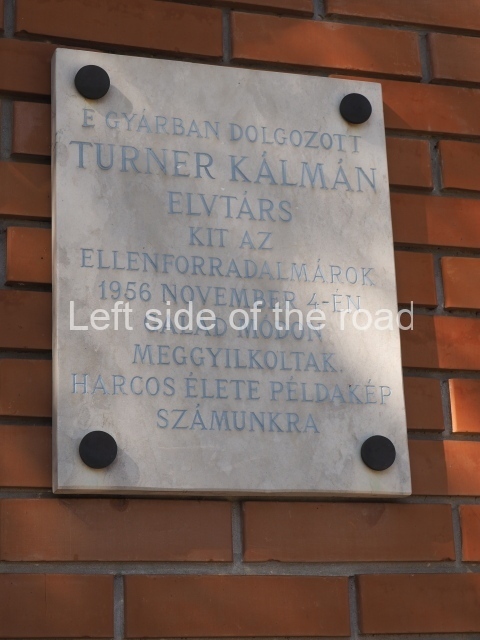

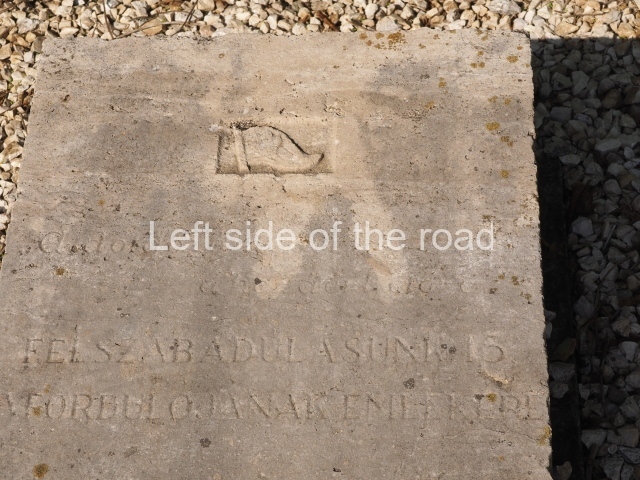

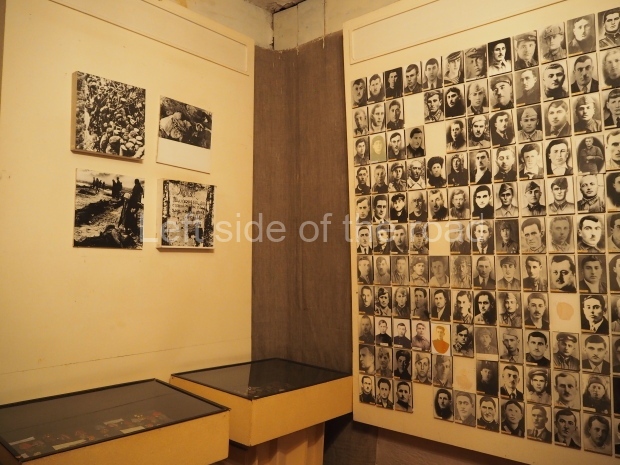

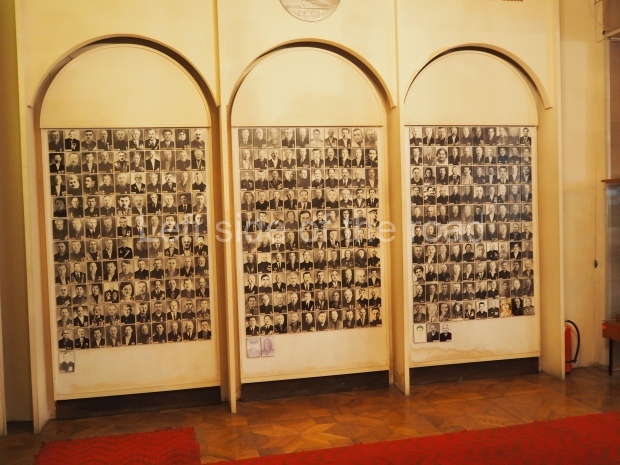

- the wall to commemorate the defeat of the Hungarian Counter-Revolution of 1956.

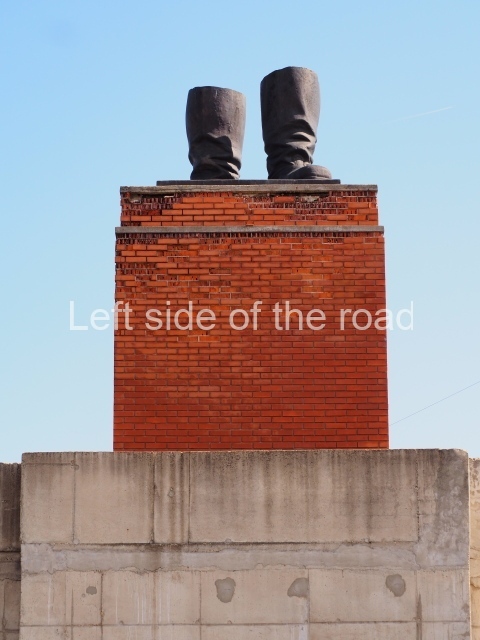

More information about all the statues in the Park can be found in the official guide book, In the shadow of Stalin’s boots.

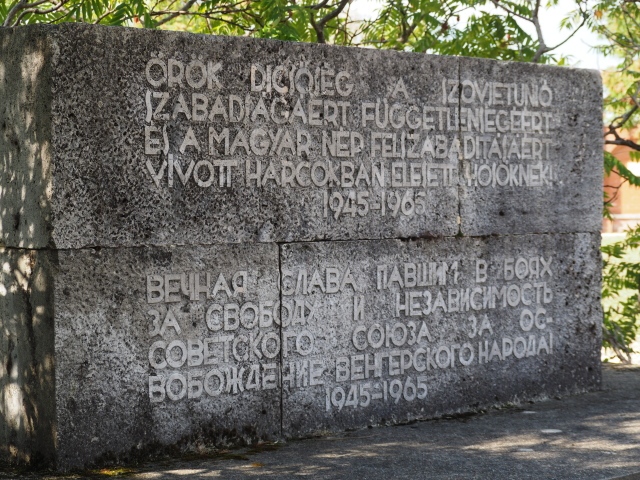

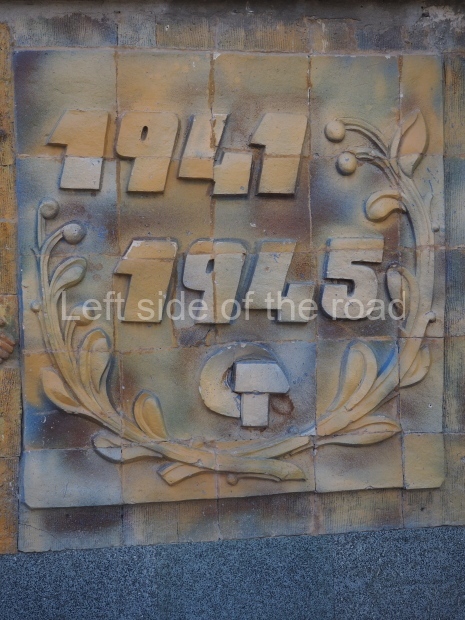

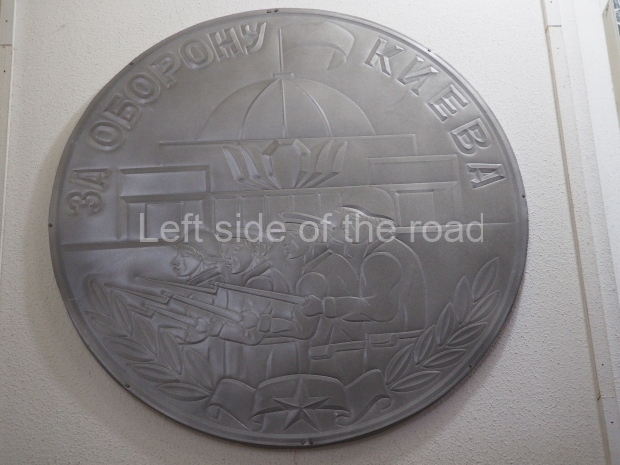

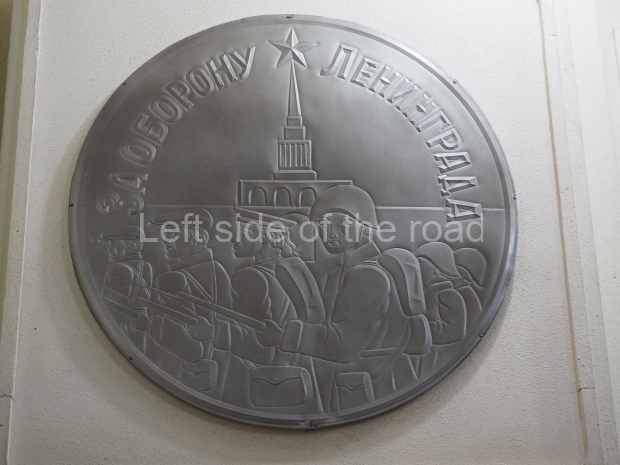

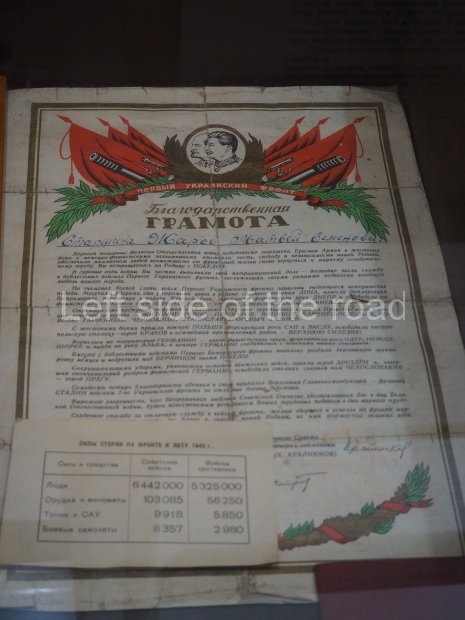

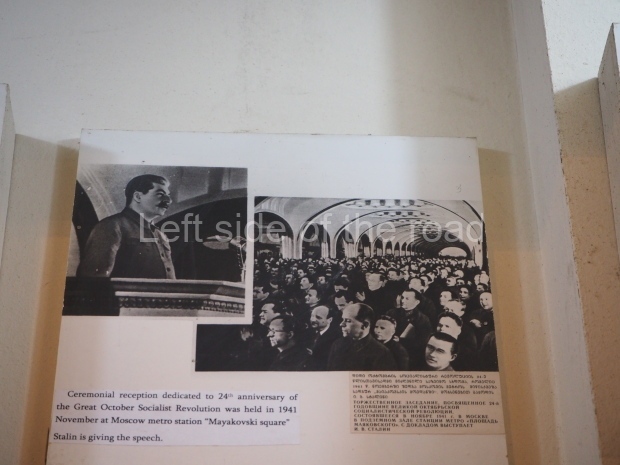

It’s a bit of a mixed message. It thinks it’s critical of the Socialist past – which the narrative puts down to be one only of Soviet occupation – but, from time to time, has to acknowledge that it was the Soviet Red Army that liberated the country from the Nazis. The only country that threw out the fascists, first the Italian and then the Germans, without the direct intervention of the Red Army, was the Albanians. The rest of Eastern Europe didn’t do it by themselves.

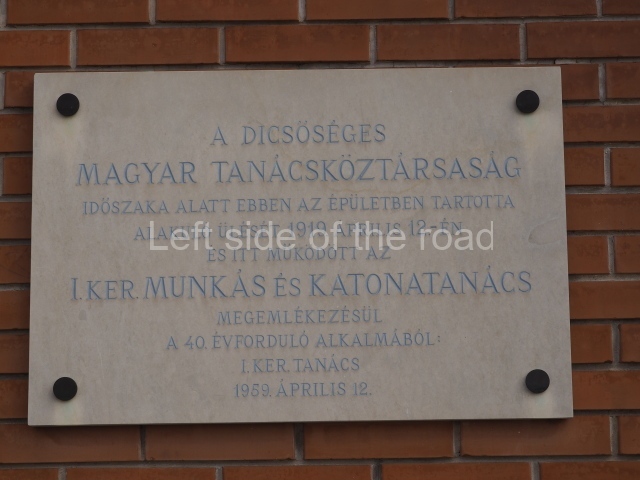

Perhaps one of the most telling statements made in the book is on page 4, second paragraph. Here it states ‘Hungary finished the Second World War in 1945 on the losing side’. By December 1944 the Red Army had surrounded Budapest but it took them 50 days to destroy the resistance of the German Nazis and their Hungarian collaborators. The remnants of this support for fascism obviously were not totally destroyed throughout the country and it was from this seed that the counter-revolution of 1956 grew – nurtured by the capitalist ‘West’.

Location;

To the south west of the city centre, just outside the official city limits.

1223 Budapest XXII. district, Balatoni út – Szabadkai utca corner

GPS;

47.42671015031753º N

18.999903359092098º E

How to get there by public transport;

From central Budapest take the Metro line No. 4 to Kelenfold, the end of the line. Once out of the metro system and in the passageway under the railway lines of the mainline station look for a sign pointing you to Örmezö which will take you to the bus station (blue buses) where you want to catch either the 101E, 101B or the 150. There’s an electronic information board as you come up from the underpass indicating how long before they depart. This is an express bus with few stops and Memento Park is the second of these, indicated on a screen as well as being announced. The second time the voice mentions a stop it is imminent. The entrance is just behind the bus as you get off, look for the black boots.

Opening times;

Everyday from 10.00 – 18.00

Entrance;

Adults; 3,000 HUF

Students; 1,800 HUF

Children (under 14) 1,200 HUF

Guide book available at the ticket counter;

2,000 HUF