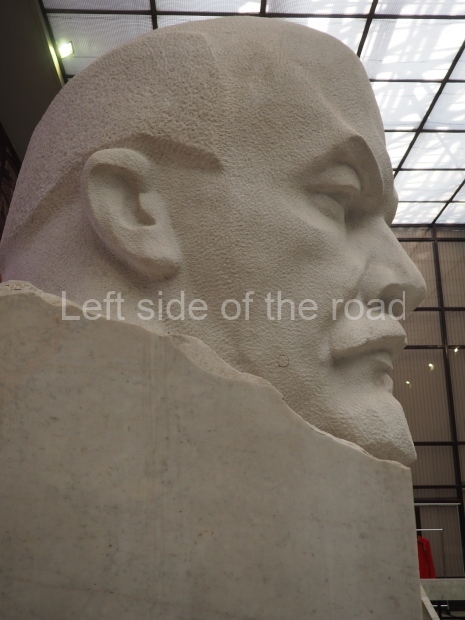

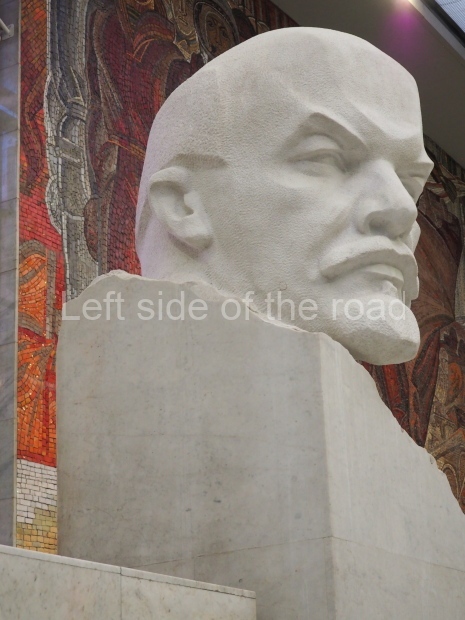

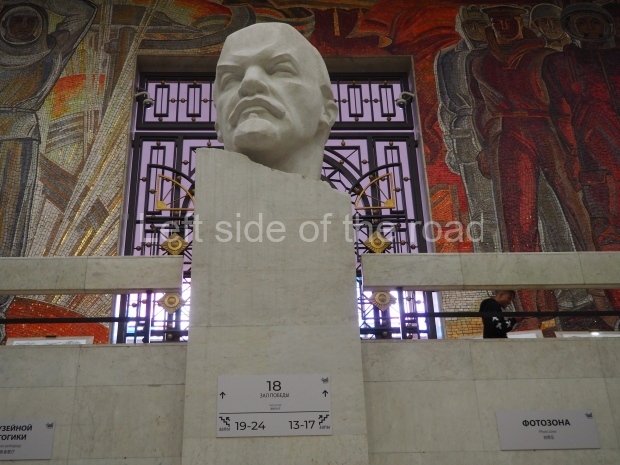

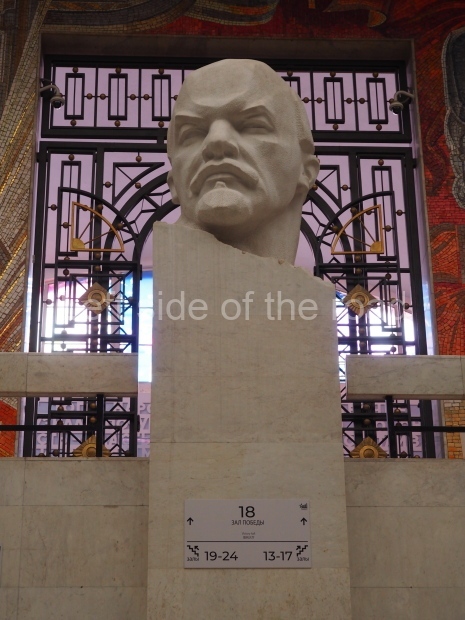

VI Lenin in Moscow

More on the USSR

VI Lenin in Moscow

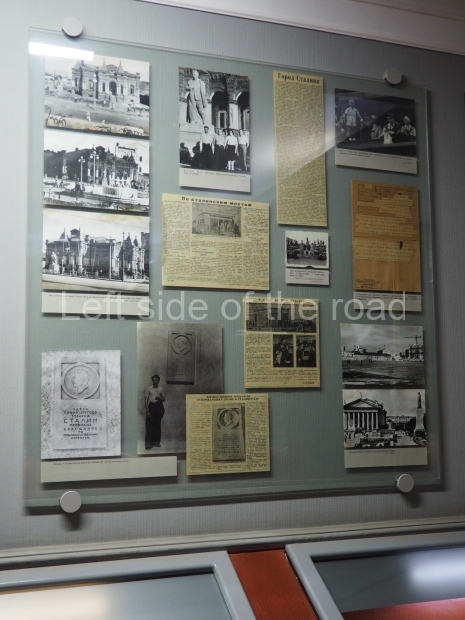

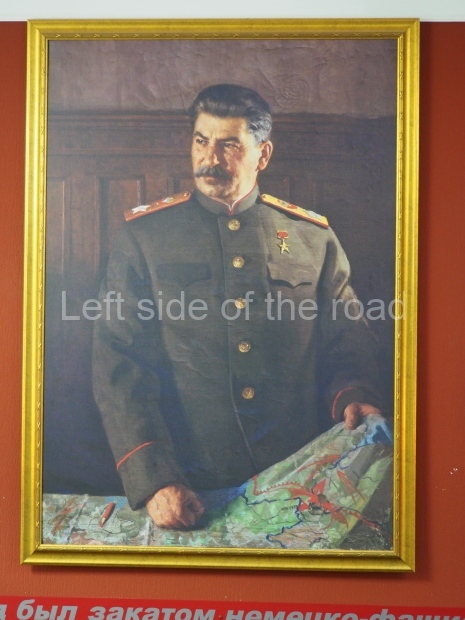

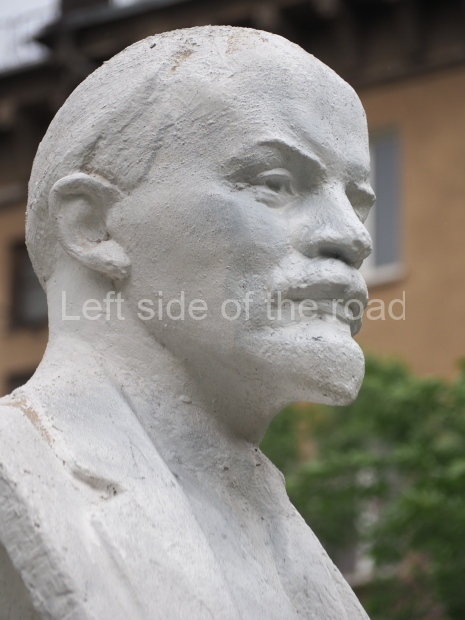

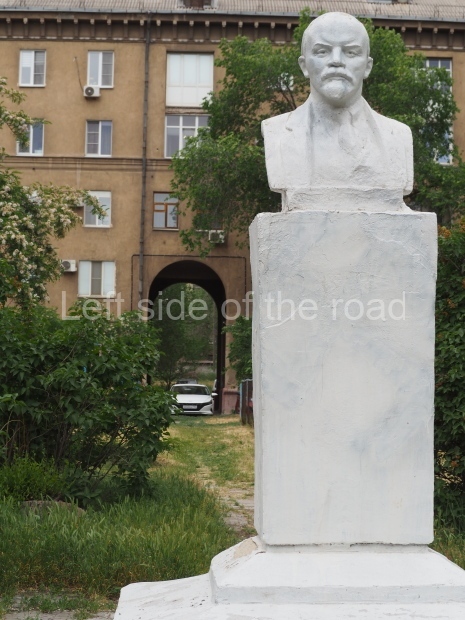

VI Lenin in Stalingrad

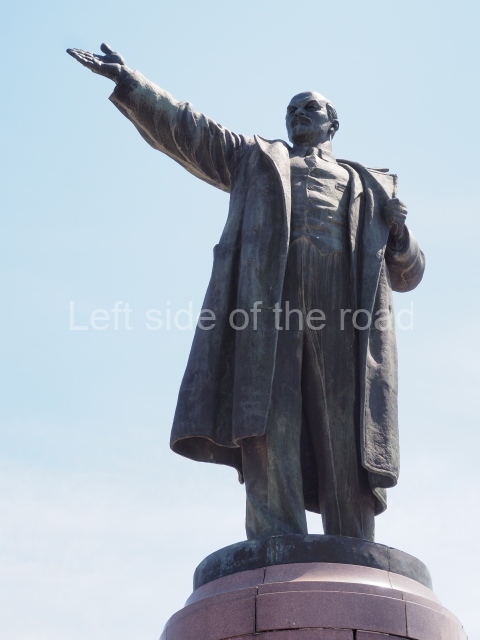

There are not as many existent statues of VI Lenin in Stalingrad (Volgograd) as in Moscow but they are relatively easily accessible by public transport and would fill a full day’s expedition for any VI Lenin statue/monument hunter.

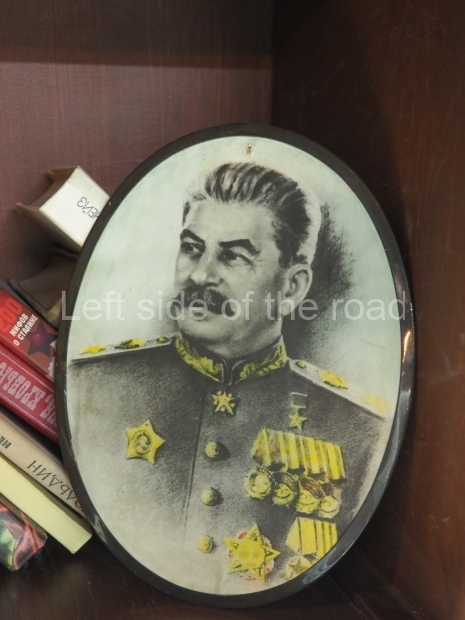

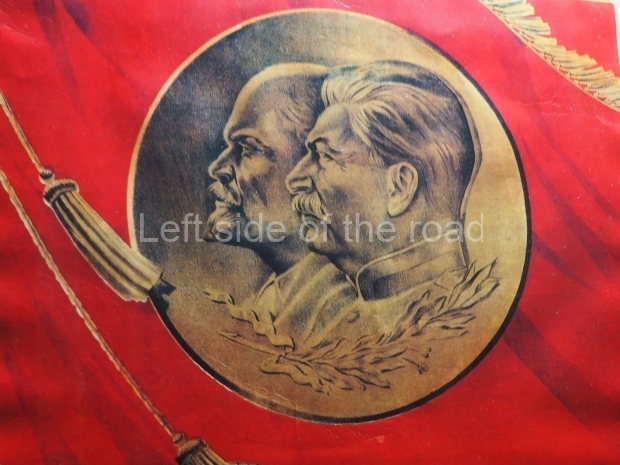

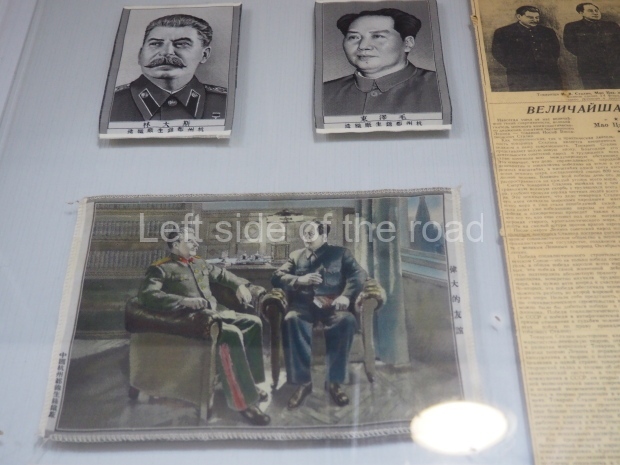

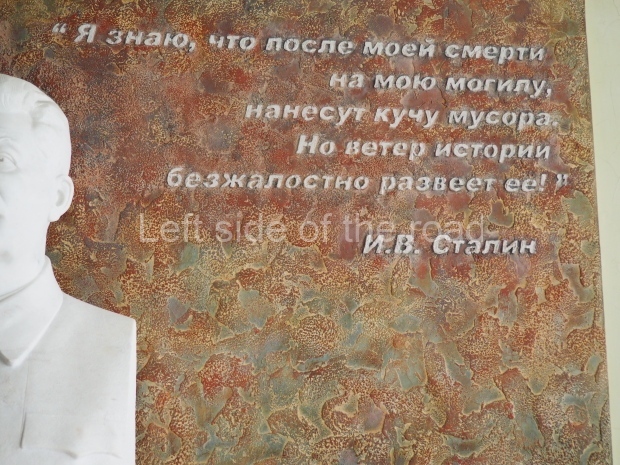

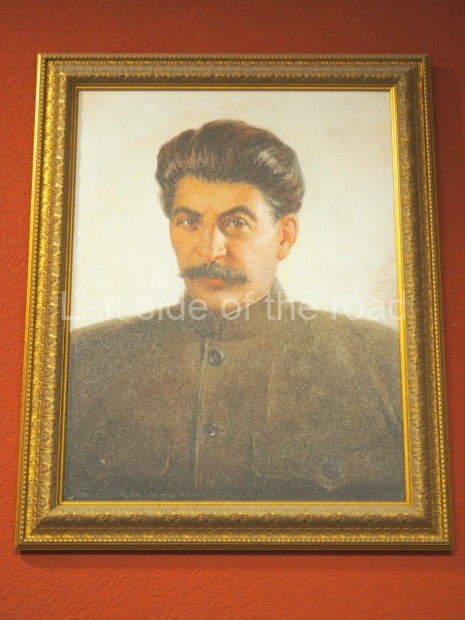

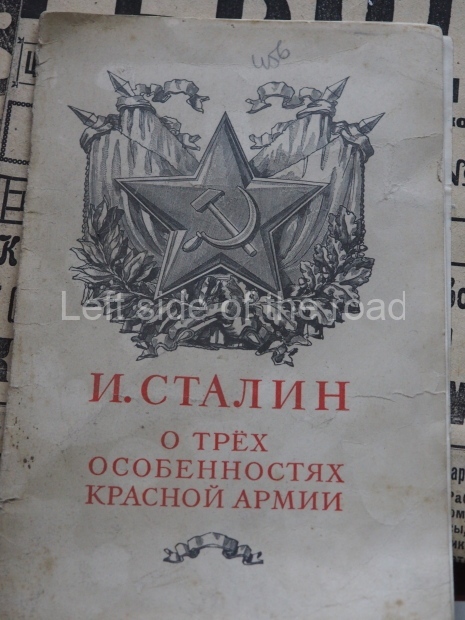

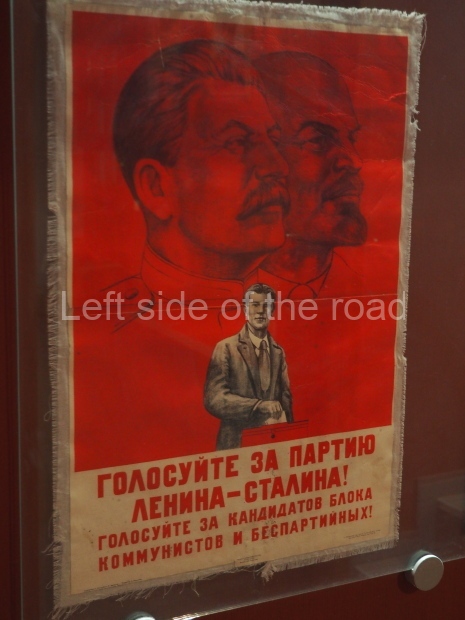

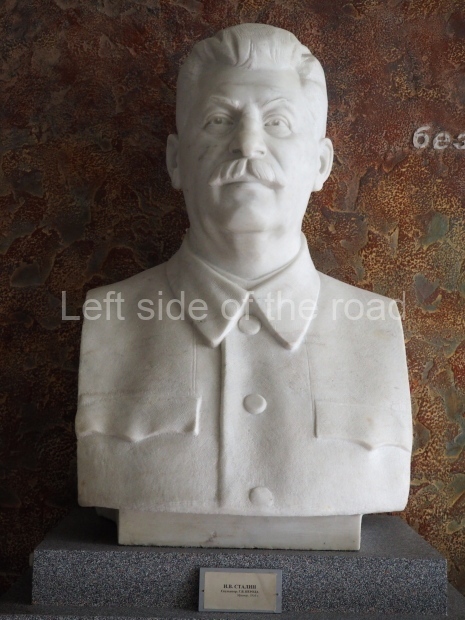

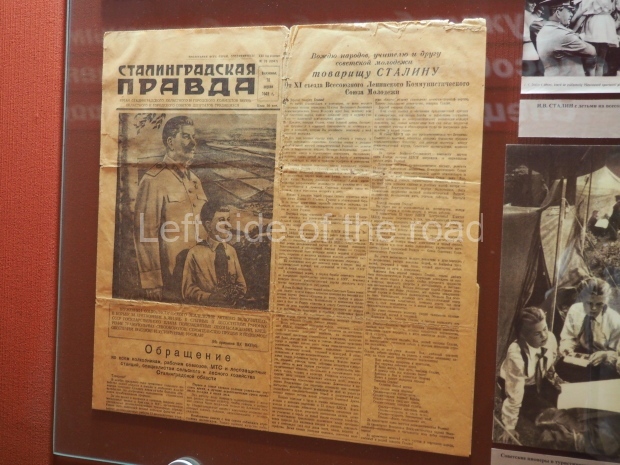

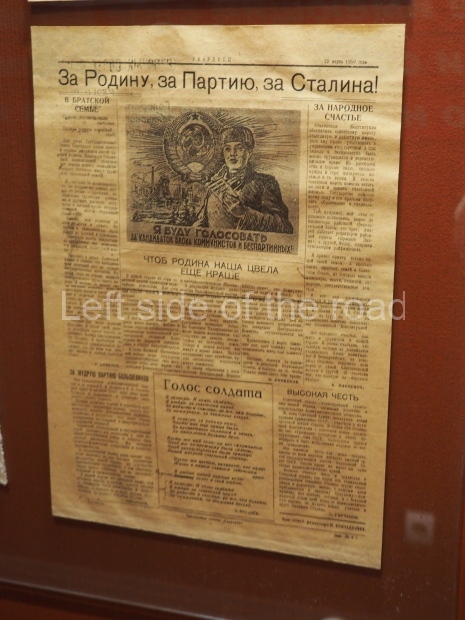

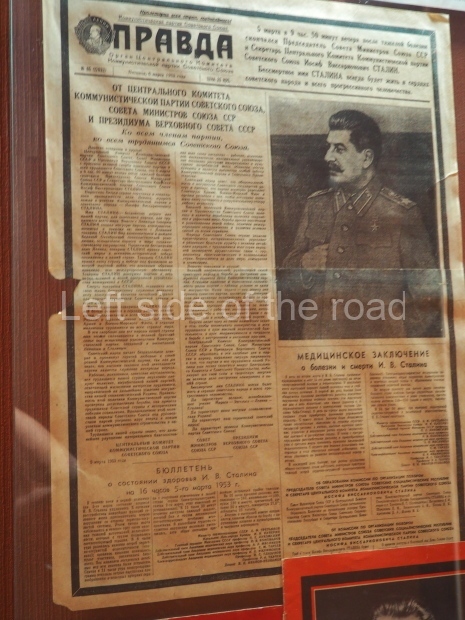

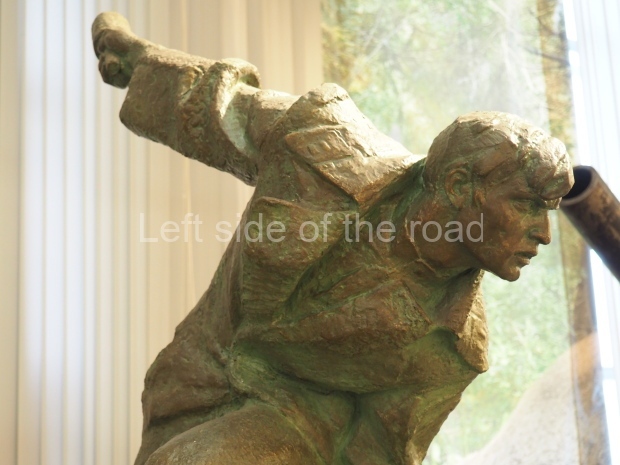

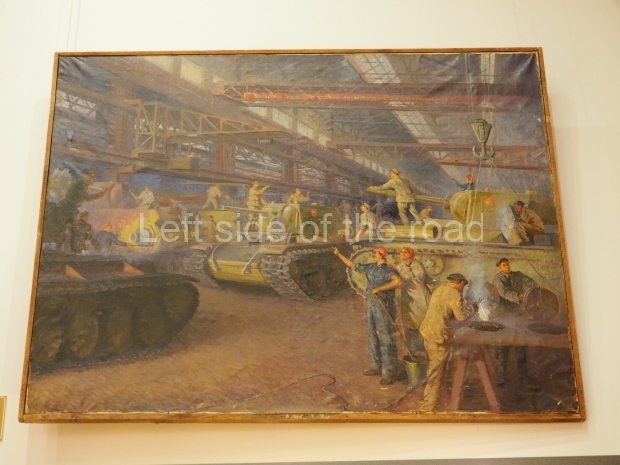

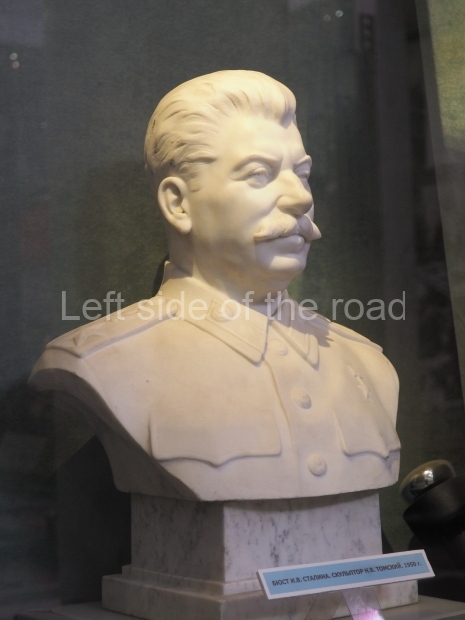

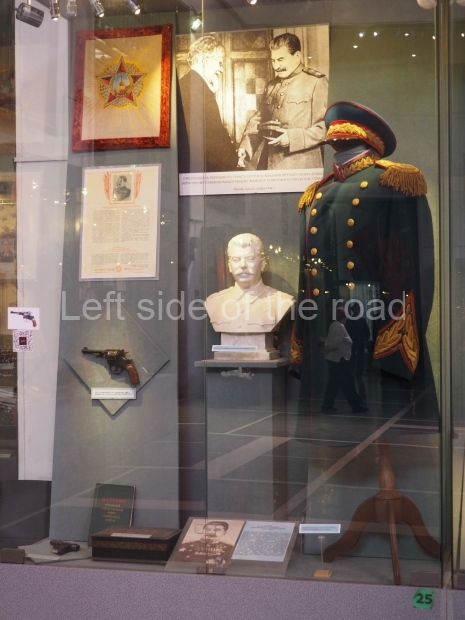

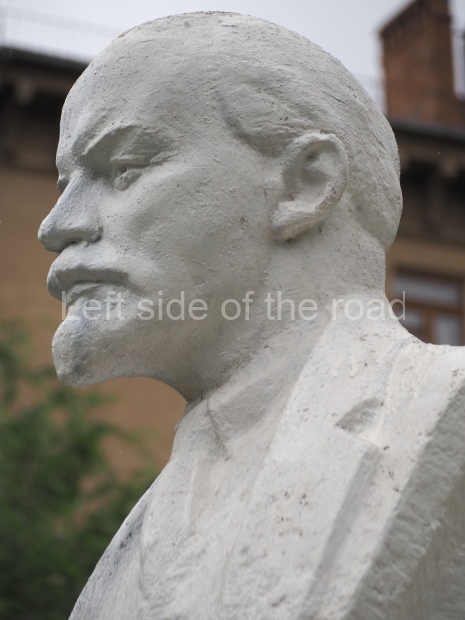

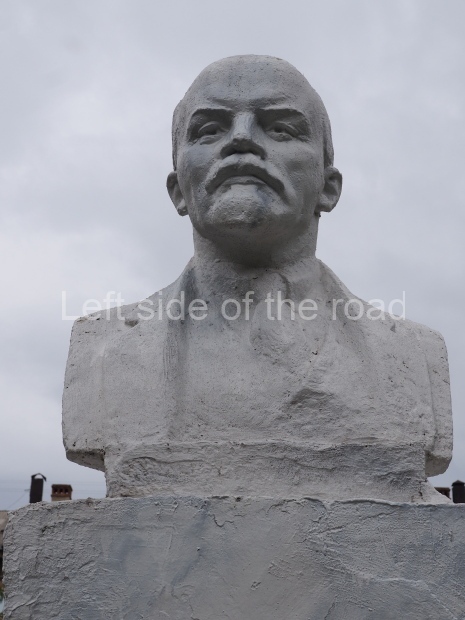

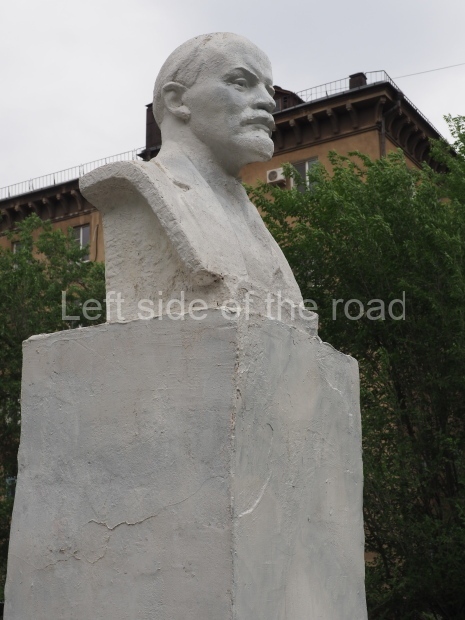

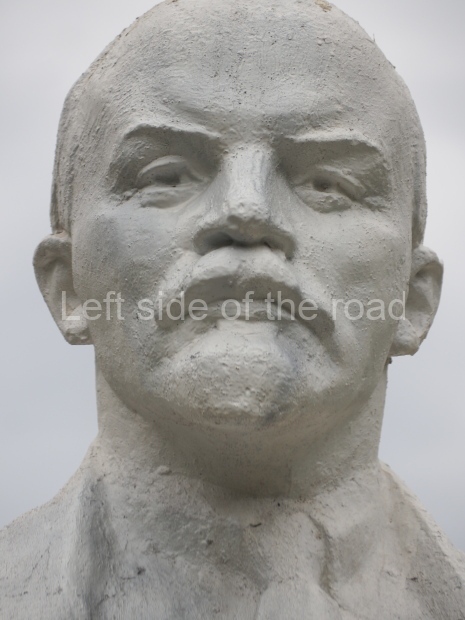

Unfortunately, many of them have been neglected and are starting to show signs of ageing. Whether the ‘rehabilitation’ that is being seen in some parts of Russia of JV Stalin (witness the unveiling of the sculptural group in the Taganskaya Metro station in May 2025) will have an effect on other Soviet period monuments remains to be seen.

In Moscow, although some of the statues of Lenin had been relegated to the Muzeon Art Park (where, if you look, many have been placed so that Comrade Lenin has his back to the viewer – intentional I have no doubt), many still in place in residential areas have obviously had some care and attention – whether professional or not is open to question.

Nonetheless, below are listed those that I was able to identify and track down within a reasonable travelling distance from the city of Stalingrad. This includes the biggest statue of VI Lenin in the world – which is located at the entrance to the Volga-Don canal and which can be reached by a (very cheap) local bus ride from the city centre – followed by a short walk along the waterside.

All the location details are accurate to the best of my knowledge but apologise in advance if I have made any mistakes. If any readers have more information about these statues – sculptor, date of installation, or any other relevant details – I would appreciate being informed of such and that detail will be added to this post in order to provide as full a picture as possible of the installation.

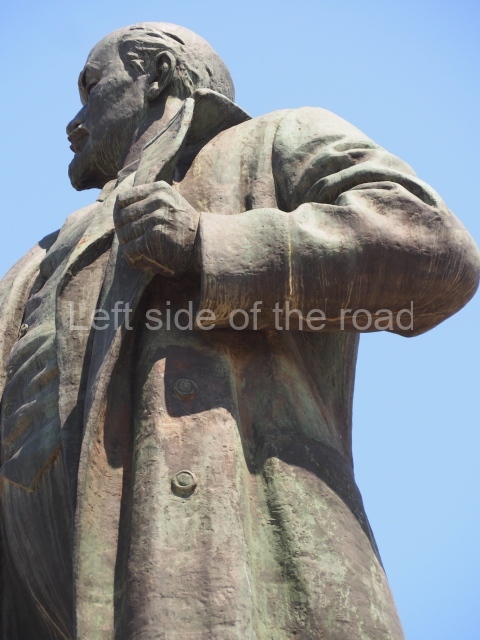

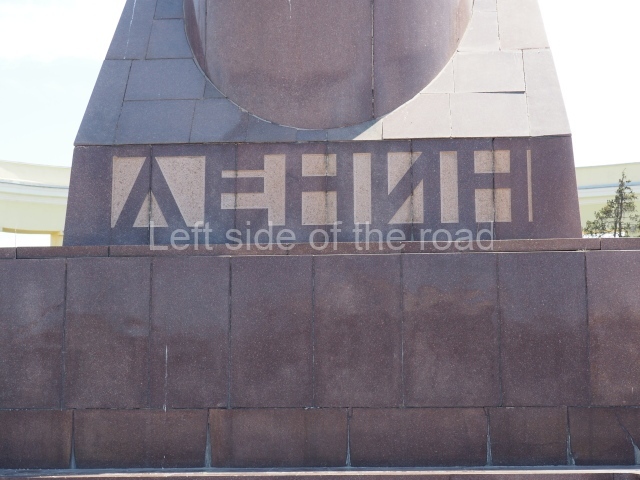

It makes sense to start with, not only the biggest VI Lenin statue in Stalingrad but, the biggest VI Lenin statue in the world. This stands beside the River Volga, at the entrance to the Volga-Don Canal.

VI Lenin at the Volga-Don Canal

VI Lenin – Volga-Don Canal entrance

Location;

On the side of the River Volga about 500m from the first lock on the Volga-Don Canal

GPS;

48.527657 N

44.559116 E

How to get there;

Take the No. 15 bus from the bottom end of VI Lenina Avenue to Krasnoarmeyskiy City. Once you go over the bridge of the canal get off the bus (it does a bizarre manoeuvre before getting to the end of its route), cross the road and head through the park that runs alongside the beginning of the canal and the entry lock. The statue of VI Lenin is about a 10 minutes walk along this path in the direction of the river (east).

More information;

The statue of VI Lenin stands 27 metres high on a 30-metre pedestal. It was unveiled in 1973, replacing a previous statue of JV Stalin – that was removed in 1961. The sculptor was EV Vucetich, the same sculptor who created The Motherland Calls! on Mamayev Kurgan.

Petrov factory settlement

VI Lenin in Elektrolesovskaya Street

Location;

In the park opposite Elektrolesovskaya Street 45/10

GPS;

48.65917 N

44.44679 E

How to get there;

Bus No. 55, among others, from the city centre goes along the main road.

School No. 53

School Number 53

Location;

At the side of the main entrance to school No. 53 at Feodosiyskaya Ulitsa 55

GPS;

48.69911 N

44.45531 E

How to get there;

Buses 2, 22 and 88 from the bus station next to Volgograd I railway station will take you to the main road at the bottom of the hill. It’s then a walk up hill, through the local neighbourhood, to the school. A little bit of imagination might be necessary to get close to the statue if the school building is closed at the time of the visit.

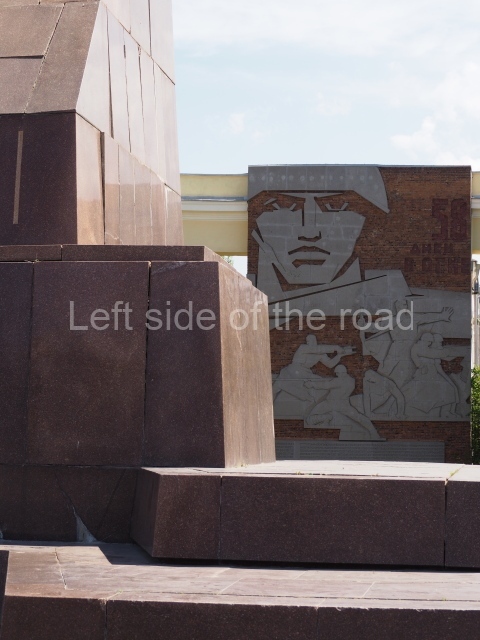

Kirovskiy City Administration

Kirovskiy City Administration

Location;

In the square in front of the Kirovskiy City Administration building

GPS;

48.570630 N

44.445727 E

How to get there;

Take bus No. 55 or 15 from the bottom end of Avenida Lenina. The square is just a short walk along a side street across the road from the bus stop.

Further information;

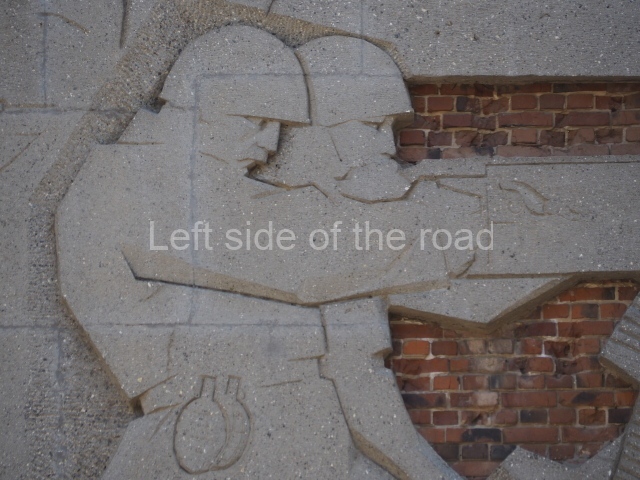

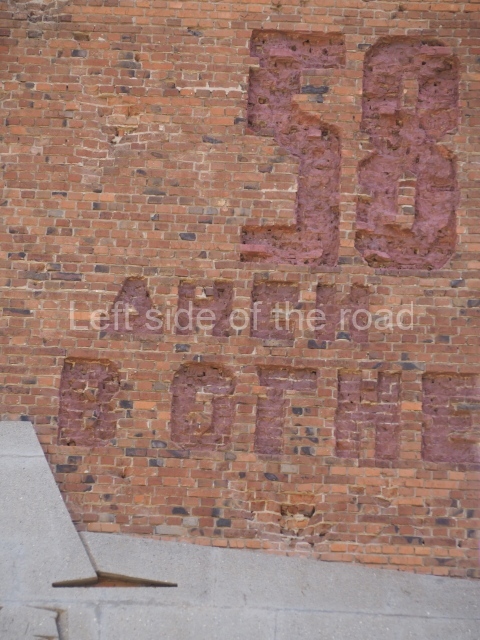

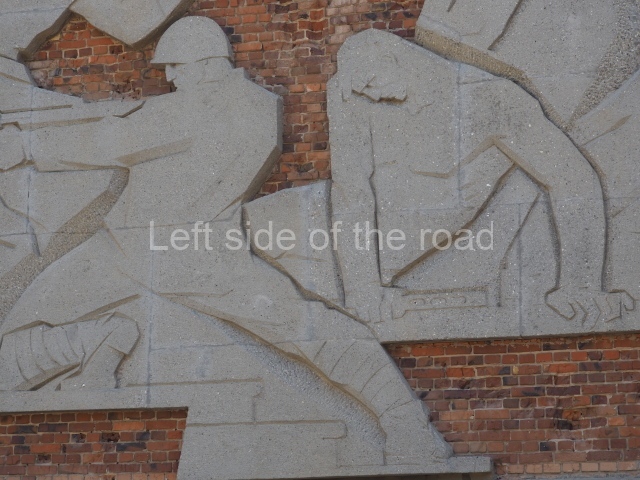

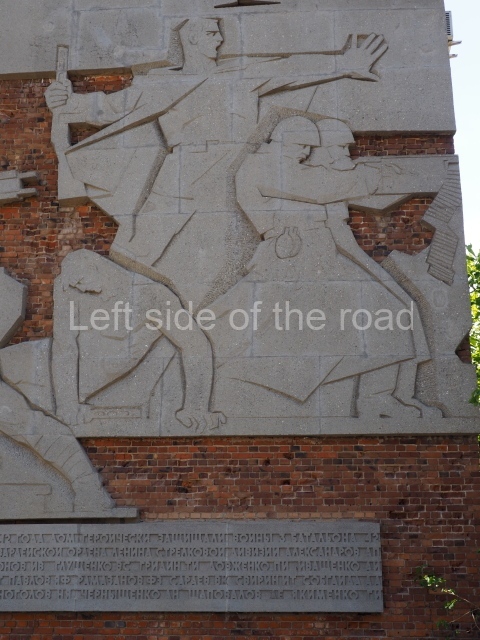

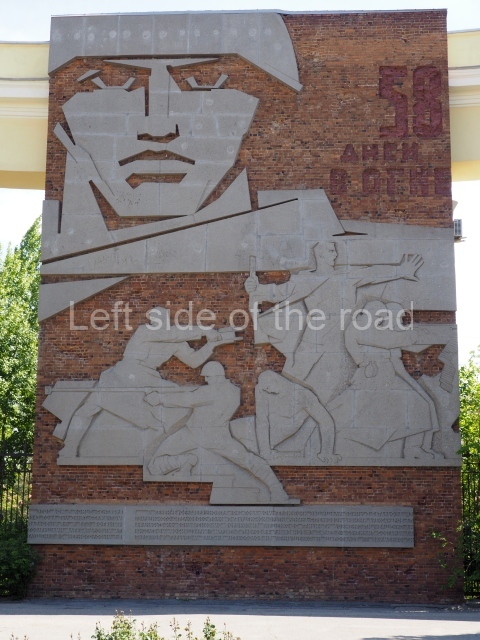

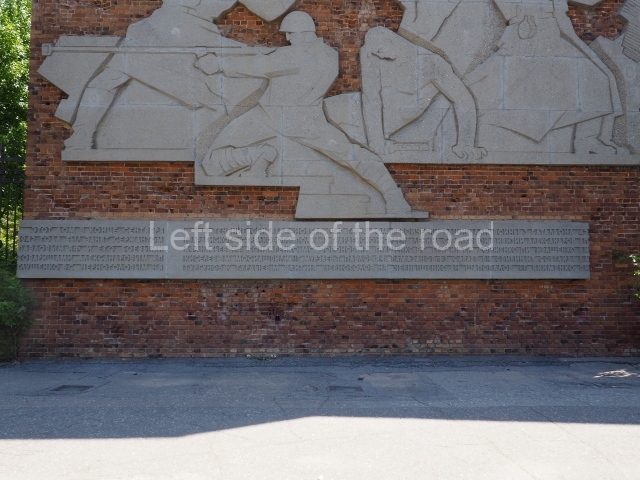

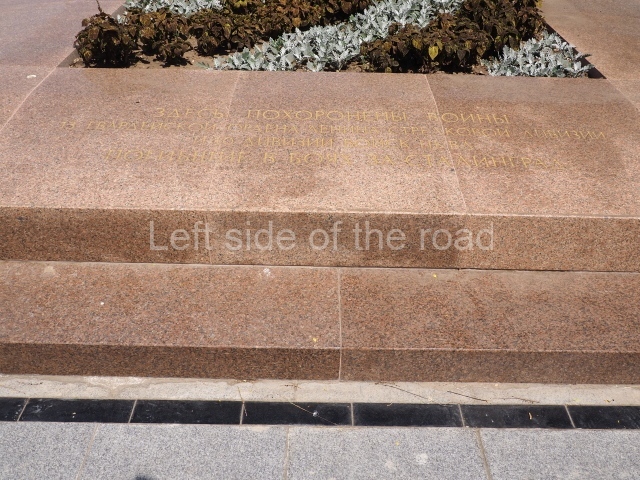

There’s a lot going on in this small area – although it is sadly in a state of neglect. The administration building is no longer being used as it was designed and this means it is on the outskirts of the community. However, as it contains the town’s War Memorial I’m slightly surprised more care has not been spent on the location.

But in this (I’m sure, at one time, a very busy) square some of the history of the locale has been recorded;

the statue of VI Lenin;

a small War Memorial to those of the town who gave their lives in the Great Patriotic War, with the names and the pictures of some from the area who were killed either in the Battle of Stalingrad or elsewhere on the front in the war against Nazism;

a plaque commemorating the visit of Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin, Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, in June 1930;

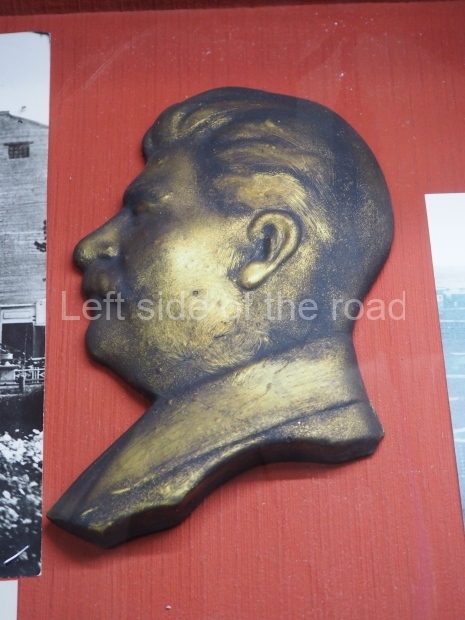

a bas relief of VI Lenin, which was installed beside the large gate in November 1930, commemorating the connection of the town to the electricity network, a result of Lenin’s call for the electrification of the whole country.

Rayon Krasny

Rayon Krasny

Location;

VI Lenina Avenue 22, Rayon Krasny

GPS;

48.75894 N

44.55350 E

How to get there;

Metro Ulitsa 39th Gvardeyskoy Divizli is a short walk away. The bust, on its plinth, is in a small garden in the middle of a housing development. This is located off the smaller road running parallel to, and just to the north of, the main VI Lenina Avenue.

VI Lenin in Zavod Barrikady

Zavod Barrikady

Location;

At the top of the steps, from the main road, in Germana Titova Square.

GPS;

48.77766 N

44.57458 E

How to get there;

The statue is directly across the road form the Zavod Barrikady Metro stop.

VI Lenin in the main post office in Stalingrad

Stalingrad Post Office

Location;

Stalingrad Main Post Office, Ulitsa Mira, 9

GPS;

48.709544º N

44.514978º E

How to get there;

The post office is a short walk from Volgograd Railway Station No. 1

Blog post: Statue of VI Lenin – Main Post Office – Stalingrad

VI Lenin in Lenin Square

Lenin Statue

Location;

VI Lenina Avenue, 32

GPS;

48.7166934° N

44.5303396° E

DMS;

48°42′59.42″ N

44°31′49.29″ E

How to get there;

The entrance/exit of the Ploshchad Lenina Metro station is right at the square. Also any bus heading in the direction of Mamayev Kurgan, from the centre of town, passes by the square. The square is also on the way to the Stalingrad Panorama Museum, the Stalingrad Siege Museum.

Blog post; Lenin Square – Stalingrad

More on the USSR

VI Lenin in Moscow