Monument to the Militia of the Proletarsky district – Moscow

Turning right just a few minutes walk from the street entrance to the Avtozavodskaya Metro station (the one that has some of the most impressive mosaics at platform level in the whole of the Moscow Metro system) is another impressive piece of art work from the Socialist period. This is the Monument to the Militia of the Proletarsky district which stands in the square at the beginning of the wide Avtozavodskaya Avenue.

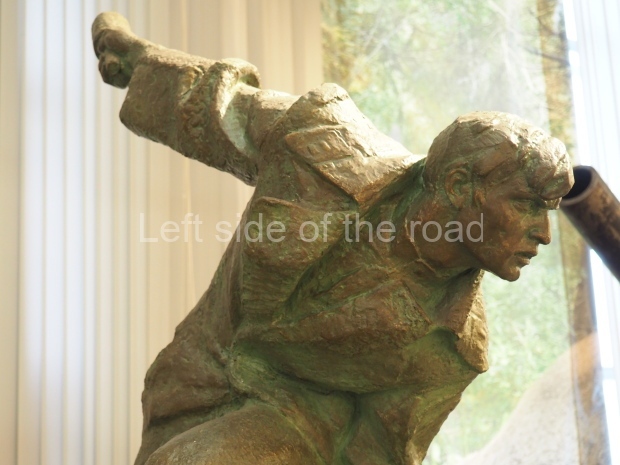

It was inaugurated on 6 May 1980 and is dedicated to the inhabitants of the Proletarsky district of Moscow who died on all fronts during the Great Patriotic War.

The team that created the monument were; sculptors Fedor Dmitrievitch Fiveysky and Nina Grigorievna Skrynnikova; architect PPI Studenikin; engineer B Dubovoy.

The principal theme of the monument is the unity of the battle front and the home front.

We are presented by a symbolic banner of victory with a central flag pole and the banner fluttering in the wind. Towards the base of the mast are the numbers – in relief – 1941 and 1945 (the duration of the Great Patriotic War) with a small, polished, copper star between the two numbers. On the side facing towards the Metro station, considered to be the front of the monument, on the right, is a group of the armed, civilian militia marching towards the conflict. On the left are uniformed Red Army soldiers, gesturing and looking in different directions. All the individuals are male – there’s no female presence on the sculpture.

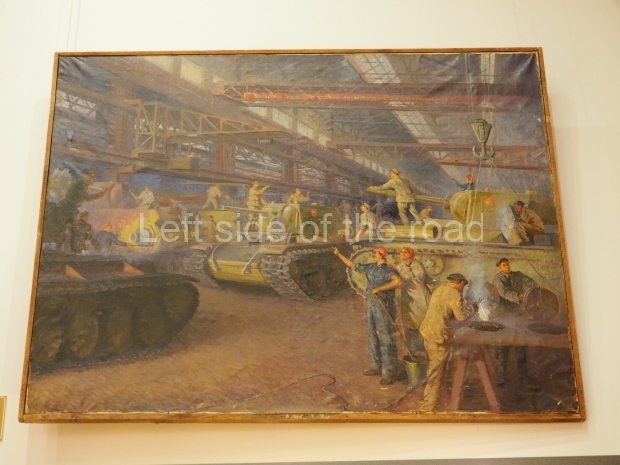

At the rear the emphasis is on the home front. Notice the apartment buildings, in the centre on the left hand side, which are surrounded by anti-aircraft guns. Barrage balloons are in the sky and at the back smoke is billowing out of factory chimneys. Rows of trucks are coming off the production line, destined for the front, and shells, ammunition and weapons are also shown as products of the factories. On the extreme left, on the edge, can be made out anti-tank defences which also constitute the monument at the point on the outskirts of Moscow where the Nazi attack was halted. (This is on the way to the present Sheremetyevo airport.)

High up, above the inscription, is a large Star, indicating this is a Socialist Moscow that is fighting and being defended by the Red Army and its people.

The inscription reads, in Russian;

Подвиг пролетариев, павших за свободу и независимость Родины, навсегда останется в памяти народа. Вечная слава героям

which translates as;

The exploit of the proletarians who have fallen for the freedom and independence of the homeland will forever remain in the memory of the people. Eternal glory to the heroes.

At the base of the mast, at the back, are the names of the sculptural/architectural team of the creators of the monument.

The sculpture is 15 metres high and the design is of copper sheeting forged on a steel framework. The whole structure rests on a stepped, polished, red granite base.

During the May 9th holiday this monument is the site of various celebratory events by both civilian and military organisations – the aftermath of one such which can be seen in some of the photographs.

(If you were to turn left from the entrance of Avtozavodskaya Metro station, go to the next junction and cross the road you will find yourself next to ‘VI Lenin amongst the fir trees’ at Avtozavodskaya Street, 23.)

Location;

Avtozavodskaya Square.

GPS;

55.70753 N

37.65856 E

How to get there;

Just a short walk from the entrance of Avtozavodskaya Metro station, on Line 2.