The Ħal Tarxien Prehistoric Complex – Malta

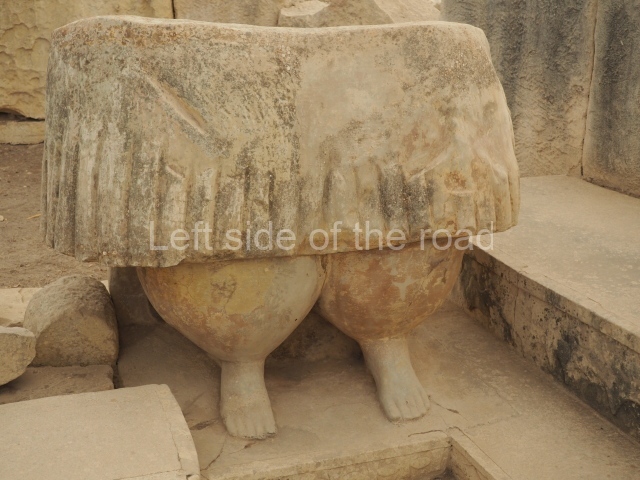

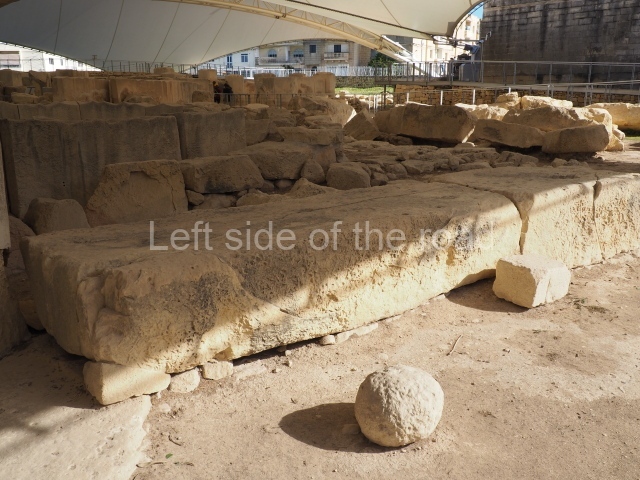

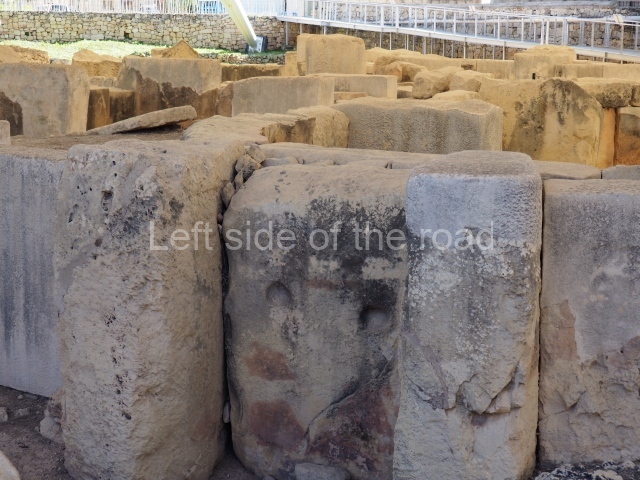

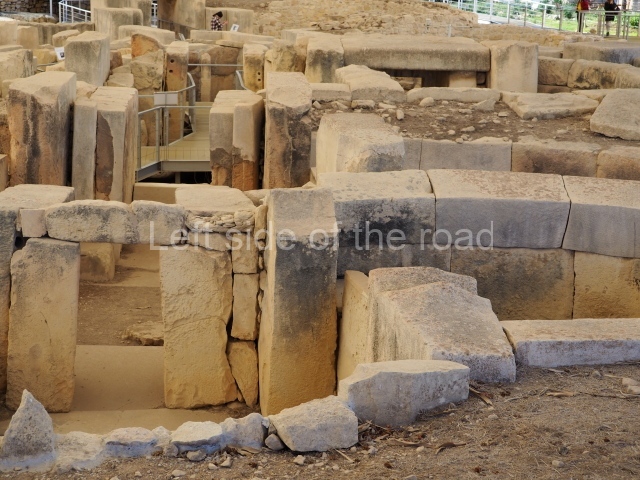

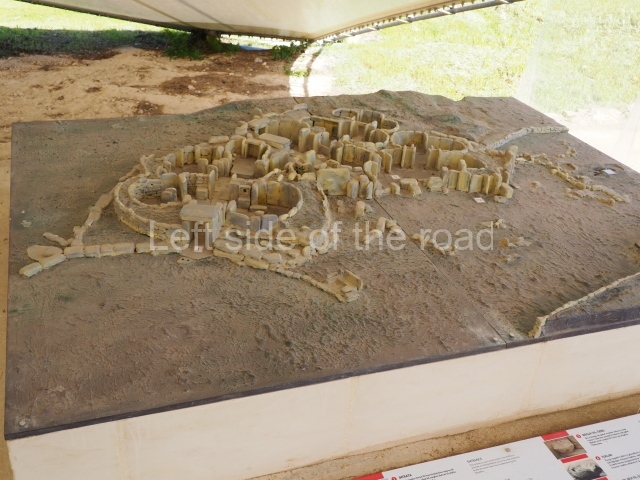

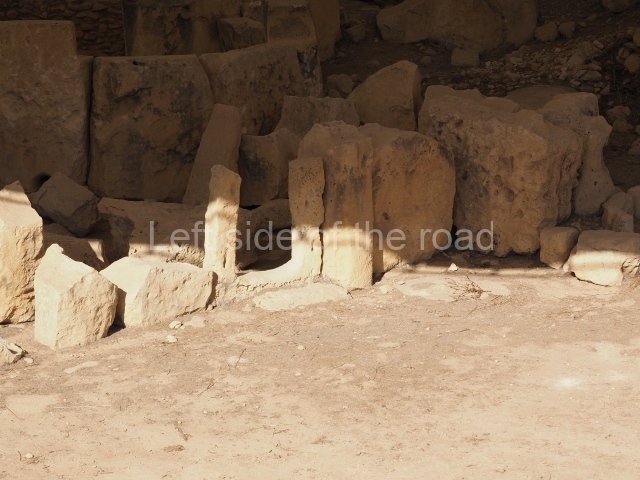

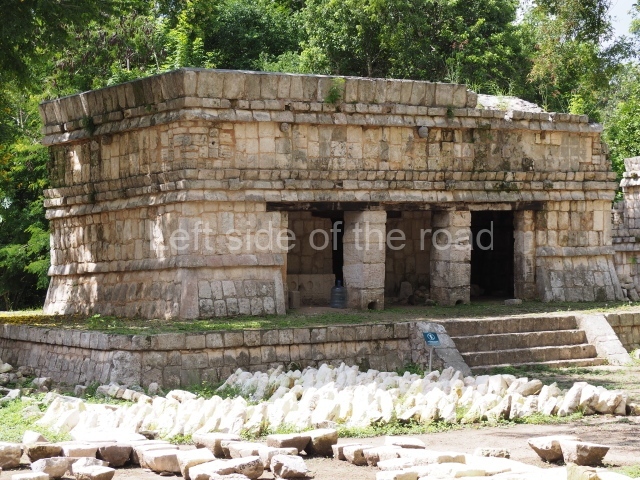

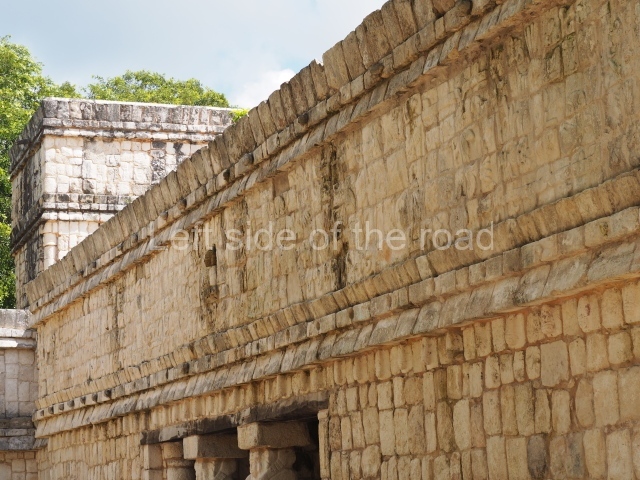

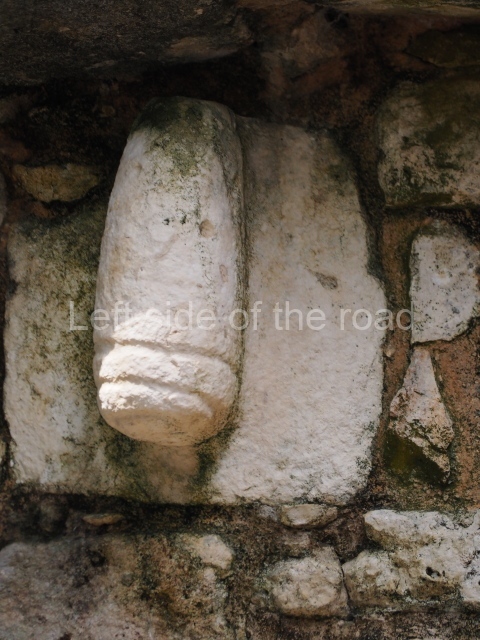

The lower part of a colossal statue of a figure wearing a pleated skirt stands sentinel to the dawn of civilization in the highly decorated South Temple within the Tarxien Neolithic Complex site. Discovered in 1913 by farmer Lorenzo Despott, the site consists of a complex of four megalithic structures built in the late Neolithic and then readapted for use during the Early Bronze Age. Only the lower part of the walls survives in the easternmost structure, the oldest part of the complex. However, it is still possible to see its concave façade and five chambers. The extensive archaeological excavations undertaken between 1915 and 1919 were led by Sir Themistocles Zammit, Director of Museums at the time.

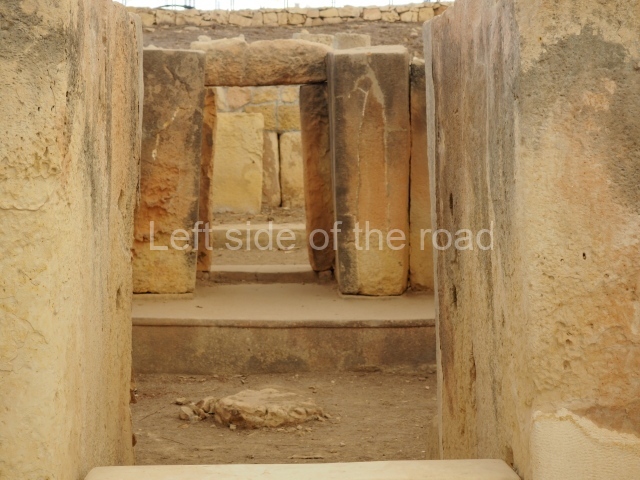

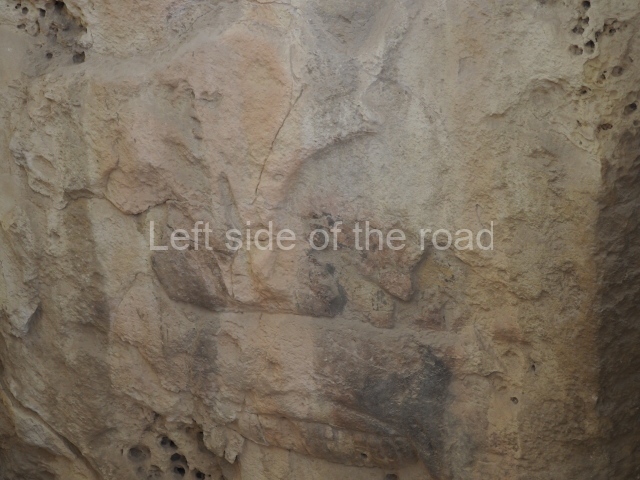

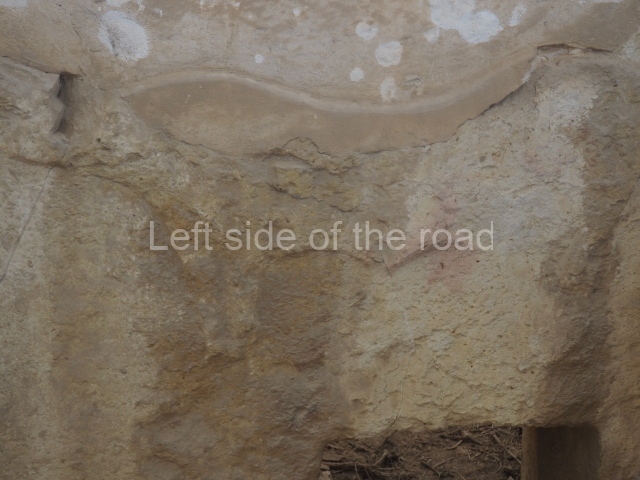

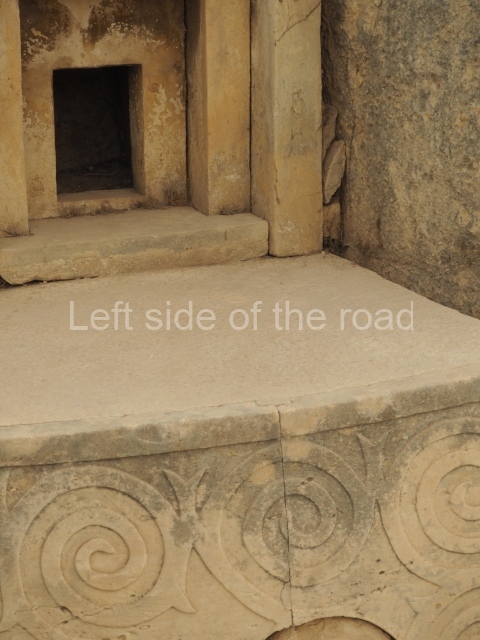

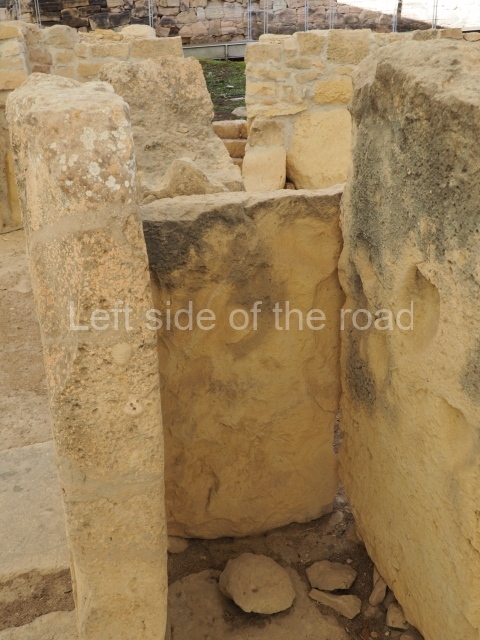

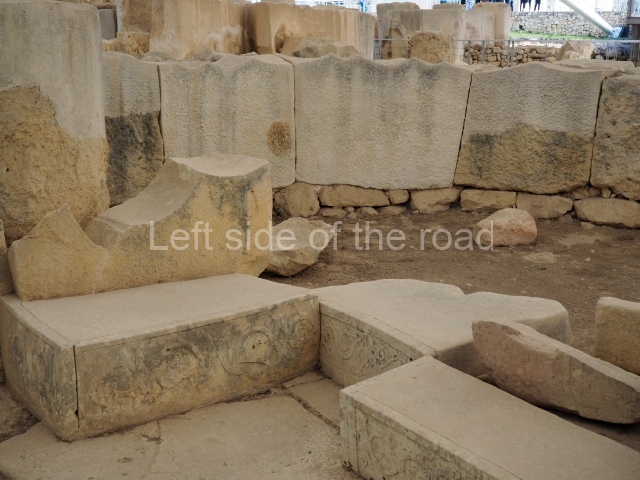

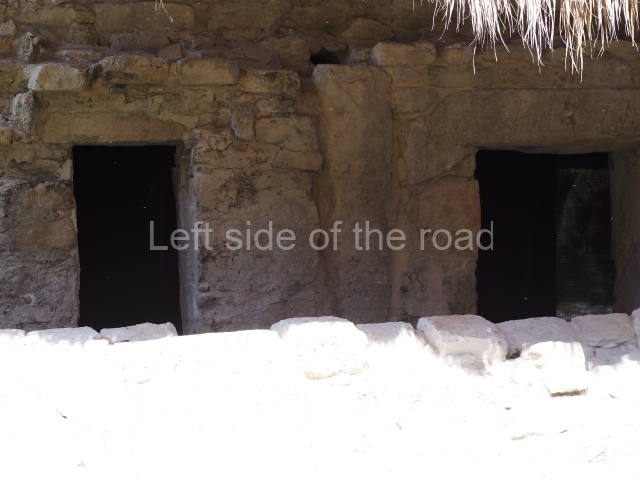

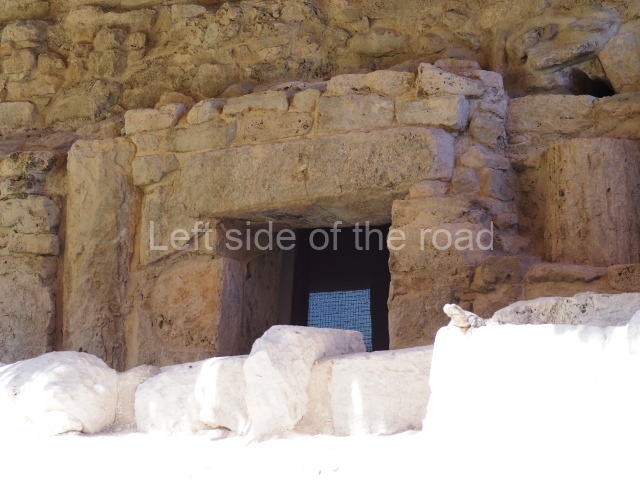

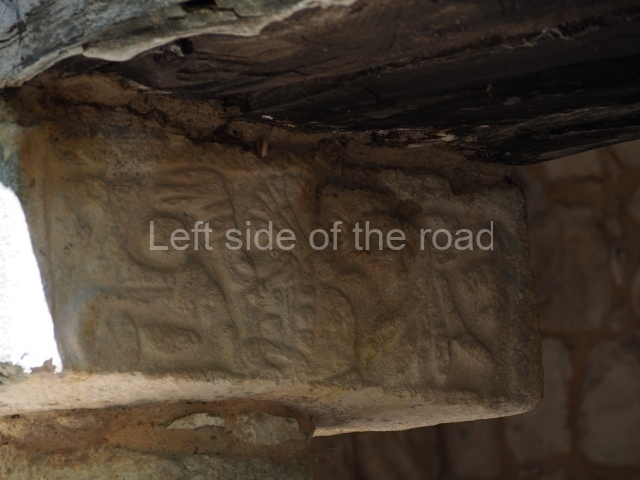

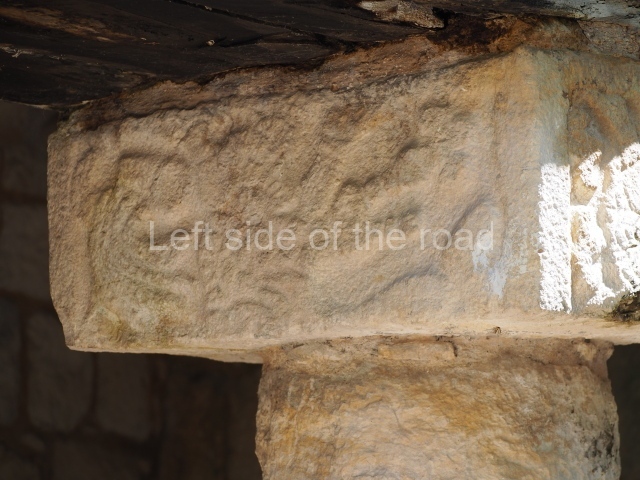

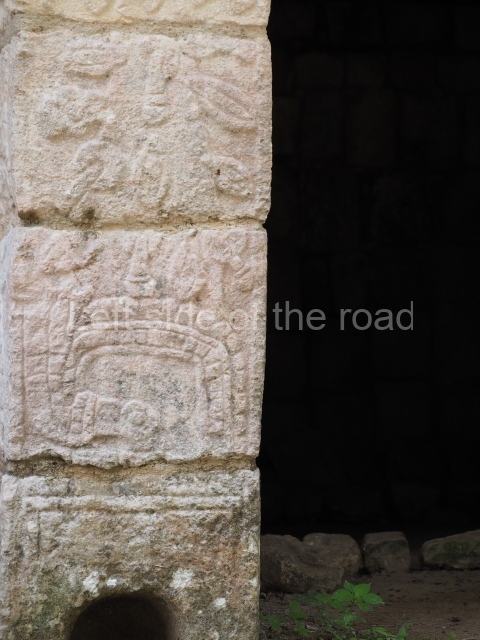

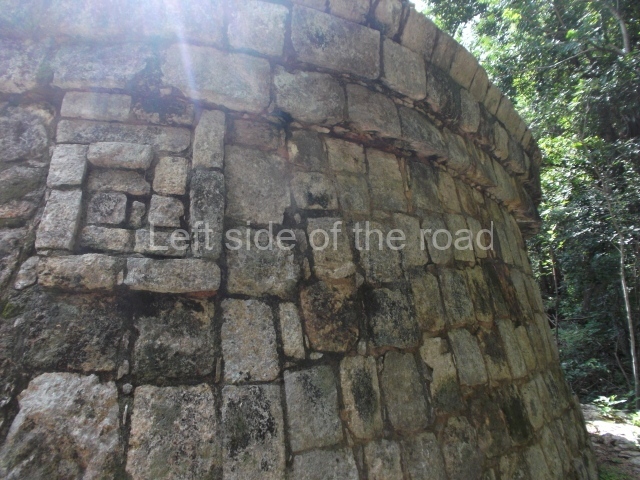

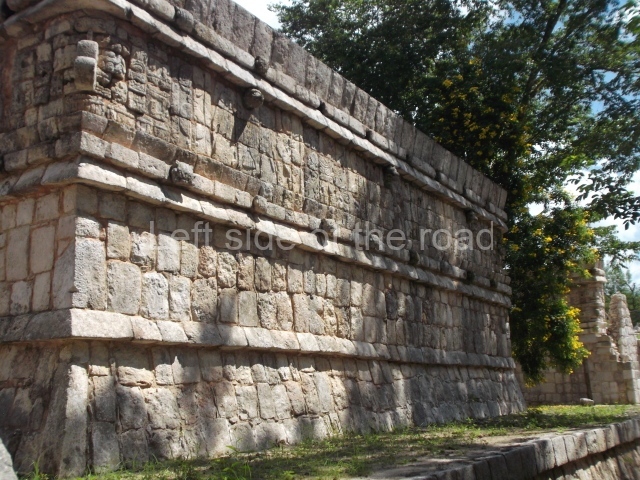

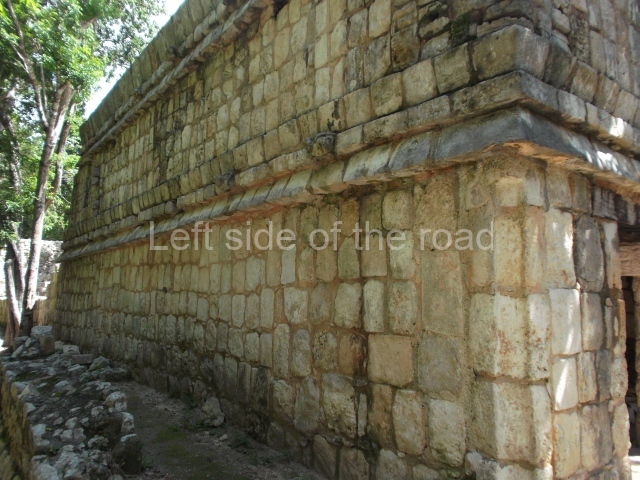

The South structure is rich in prehistoric art, including bas-relief sculpture depicting spirals and animals. The domesticated animals depicted include goats, bulls, pigs, and a ram. [The originals of these are now on display at the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta.] The large number of animal bones discovered in this complex, most of which were found in specific areas, indicates the importance these animals played at the time. The eastern building follows the traditional design of these megalithic structures, with a central corridor flanked by a semi-circular chamber on each site. Evidence of arched roofing in the unique six-apsed Central Structure, the last of the four to be built, helps visitors imagine how these temples might have looked when covered.

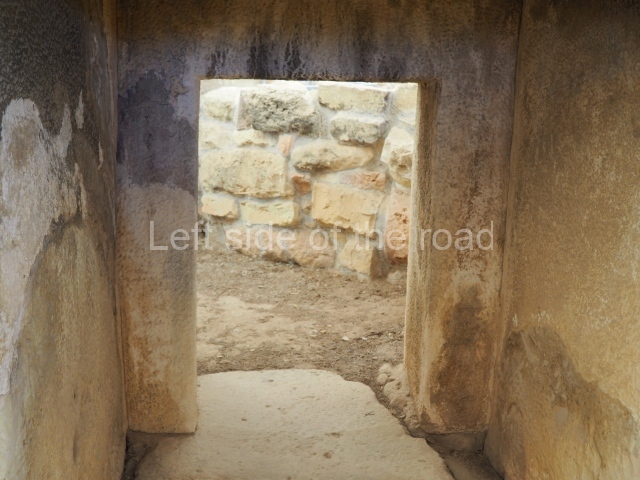

Passages between different areas of the complex are sometimes blocked by physical barriers, suggesting that parts of these buildings were accessible to only a part of the community. A large hearth in the corridor between the first apses and a smaller one in the corridor between the second pair of apses of the central structure are evidence of the use of fire within. Although we know little of what took place within these buildings, evidence suggests that they were important structures central to the lives of the Neolithic inhabitants of the island. In the early Bronze Age (after 2,000 B.C.), new arrivals to the islands turned some areas within the site into a cremation cemetery, leaving a rich record of customs and objects.

The text above from Heritage Malta.

Now a few comments by me;

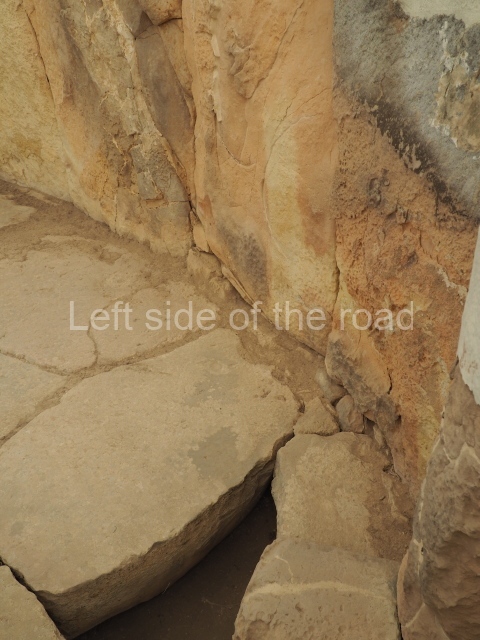

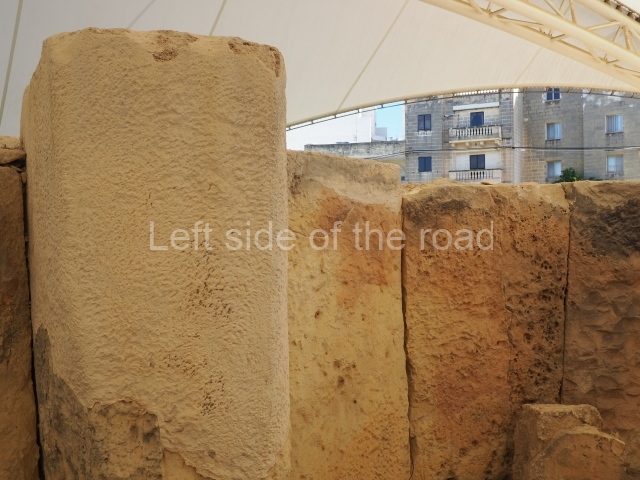

As with many archaeological sites world wide those which were excavated in the early 20th century underwent what would now be classified as vandalism. In place of just re-positioning fallen stones those that were broken were ‘repaired’ with modern materials, in this case concrete. Although much of the time this is obvious at others the thinking of the time of the use of the structures meant that assumptions were made using ‘modern’ prejudices and this might have distorted the restoration.

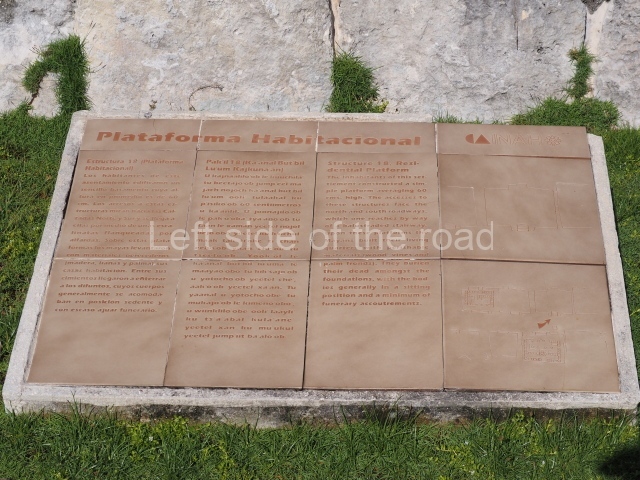

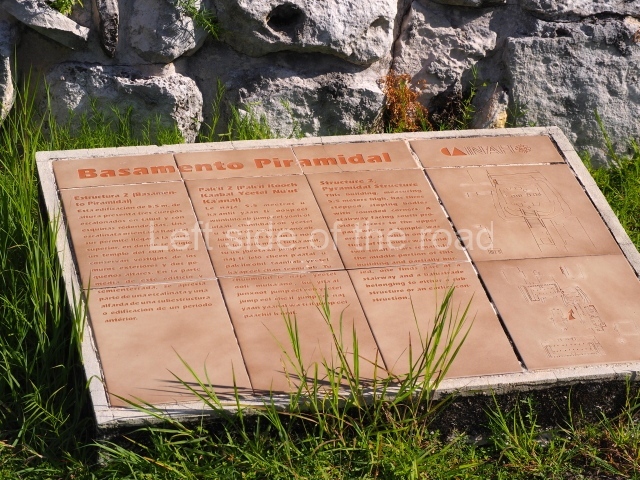

Late 20th and early 21st century thinking started to consider that the best form of maintaining these ancient structures was to remove any especially unique artefacts, e.g., some of the carved stones, and replace them with contemporary copies – the originals being placed, in this case, in the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta. Where that has happened at Ħal Tarxien the information boards inform the visitor of such.

In fact, to get a full appreciation of this site (and the others on the islands) a visit to the National Museum of Archaeology is invaluable as it puts the finds into context with the other sites that have already been excavated.

Location;

Ħal Tarxien, TXN 1063, Malta

GPS;

35º 52′ 9” N

14º 30′ 43” E

How to get there;

Buses 81 and 82 leave from the Valletta bus station. From the Ħal Tarxien bus stop walk back on yourself, take the first road on the right and the entrance to the complex is about 150m away.

Opening;

09.00 – 17.00

Entrance;

Adult; €6

Over 60; €4.50