El Rey – Quintana Roo

Location

The pre-Hispanic settlement is situated on Cancun Island. Measuring 21 km in length and 400 m at its widest, this is a long strip of land delimited by the Caribbean to the east and by Lake Nichupte to the west. It is surrounded by vast wetlands and mangroves. No one knows the original name but the present-day one is a reference to a sculpture of a human face with an iguana headdress found at the site. El Rey is the largest and most important of the 12 pre-Hispanic sites on the island and chronologically corresponds to the Late Postclassic. It coexisted with San Miguelito, the second largest, Yamil Lu’um (‘undulating land’), Punta Cancun and Pok Ta Pok. However, some of the settlements on the island date back to the Late Preclassic, the most important of which are Coxolnah or ‘house of the mosquito’, situated on a peten or island in the lake area, and El Conchero, a mound of shells and conches left by mollusk-gathering human groups.

History of the explorations

The first geographical reference to the Island of Cancun or Cancuen can be found on a map from 1776 drawn up by the cartographer Juan de Dios Gonzalez. During the 19th century, the island was visited by Captain Richard Owen Smith, John L. Stephens and the Englishman Frederick Catherwood, Alice and Augustus Le Plongeon, William H. Holmes, C. Arnold and F. J. T. Frost; the latter two produced the first drawing of the anthropomorphic head that lends the site its name. In the 20th century, Thomas Gann and Samuel K. Lothrop produced descriptions of various structures as well as several maps and photographs. In 1954, William T. Sanders conducted the first excavations in an attempt to find ceramic materials that would indicate a timeline for the sites of El Rey and San Miguelito. Nine years later, Wyllys Andrews IV led excavations at El Conchero. In the 1970s, Pablo Mayer Guala of the INAH launched the first official research and consolidation project at El Rey. In the subsequent years, the same institution has conducted various consolidation and maintenance works, led by Enrique Terrones G.

Pre-Hispanic history

When the Spaniards arrived with Francisco Hernandez de Cordoba in 1517, the Yucatan Peninsula was divided into 19 chieftainships and Cancun Island belonged to Ecab. The principal economic activities were fishing, farming and the production of salt, honey, copal (a type of resin) and cotton. Between the 13th and 16th centuries, these products were traded via a vast network of terrestrial and maritime routes covering every coast on the peninsula, from Campeche to Central America. Thanks to its location on the edge of the island and status as just one of several coastal enclaves in the pre-Hispanic commercial network, El Rey was able to trade its marine products: dried fish, stingray spines, utensils and ornaments made of shell and conch. In the same way, various foreign goods were imported into the region: basalt grinding stones, knives and flint projectile points, obsidian cores and daggers, beads and earrings made of jadeite and quartz, rings, ornamental bells and copper tweezers. The limited terrain and saline soil shaped the economy of the ancient inhabitants of Cancun Island. Farming alone could not support a large population where scaly fishing, gathering mollusks and turtles provided the staple diet. The island’s occupants build underground pits (chultunes) to store rainwater and supplement the natural sources of fresh water from cenotes and sinkholes.

The pre-Hispanic occupation of the site is denoted by the Tases ceramic group, essentially composed of the Payil, Mama, Navula and Matillas varieties, the latter obtained through trade with the Gulf region of Campeche and Tabasco. The Spanish Conquest led to the disintegration of the trade network on the Caribbean coast, with serious consequences for communities such as El Rey. All the coastal settlements entered a population decline and between the 16th and 18th centuries became prey for English, French and Dutch pirates.

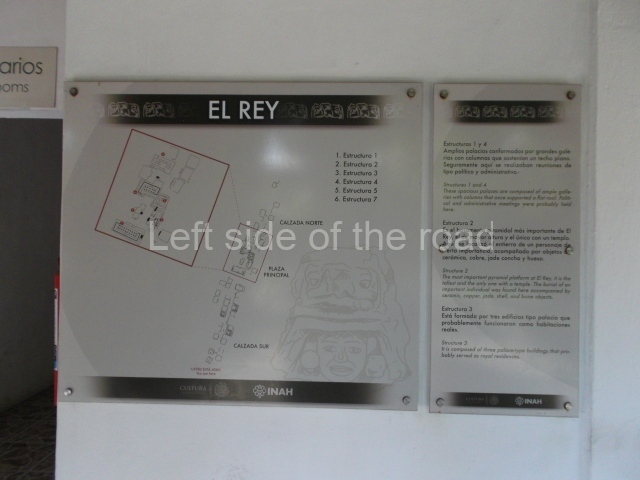

Site description

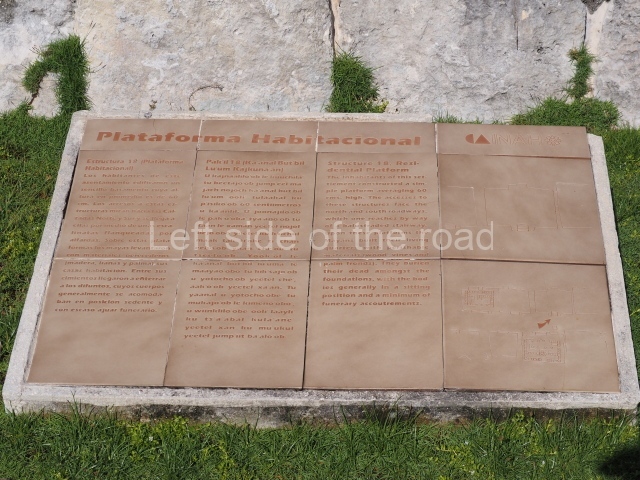

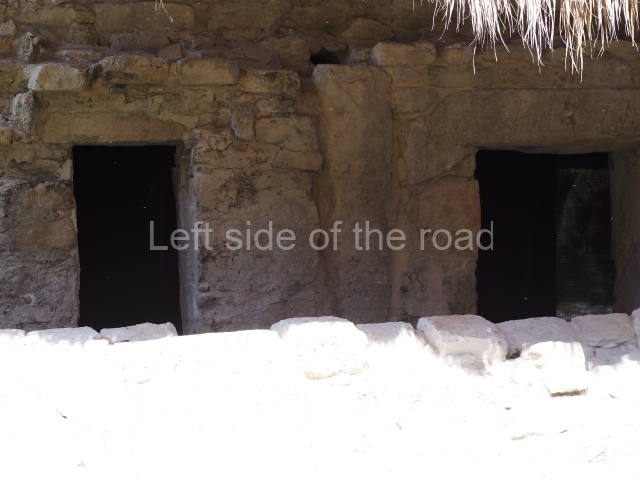

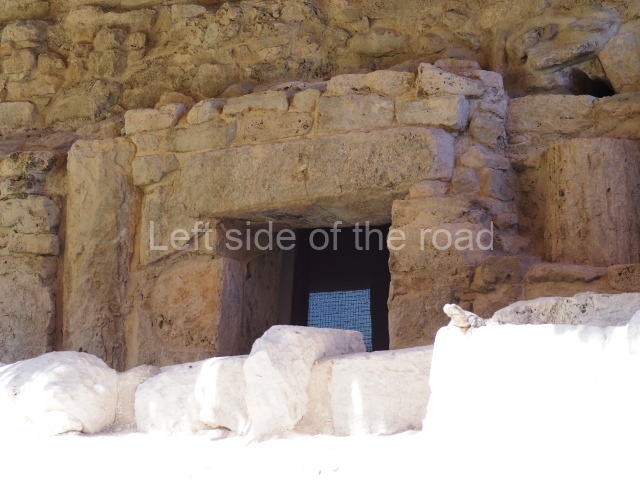

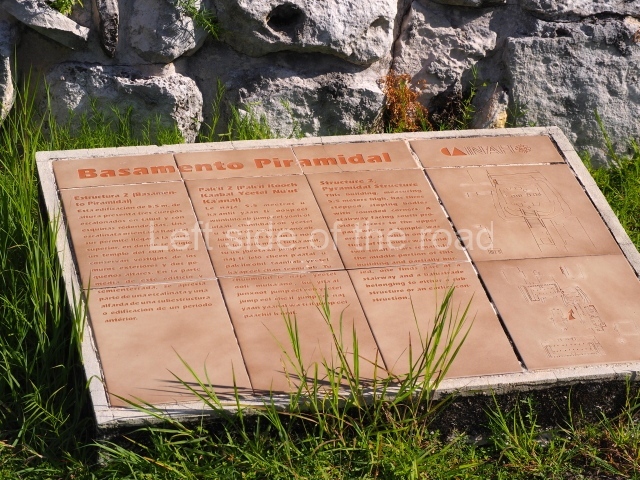

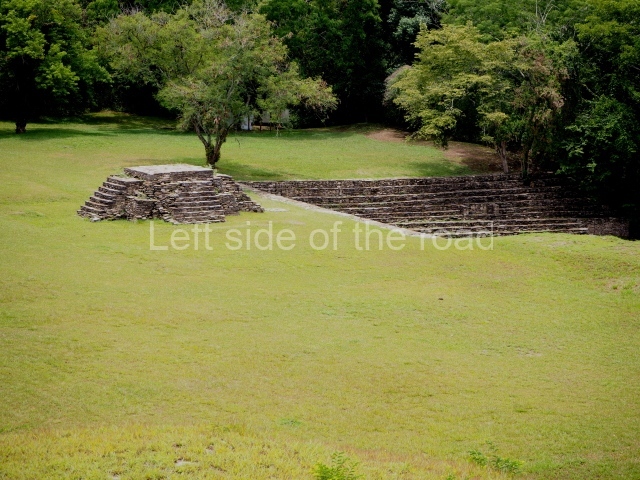

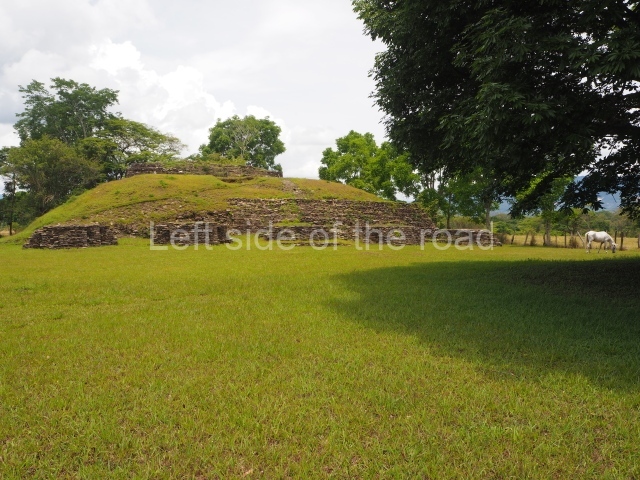

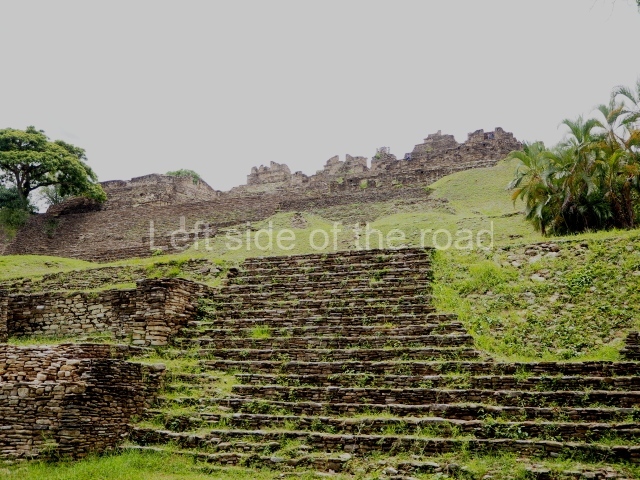

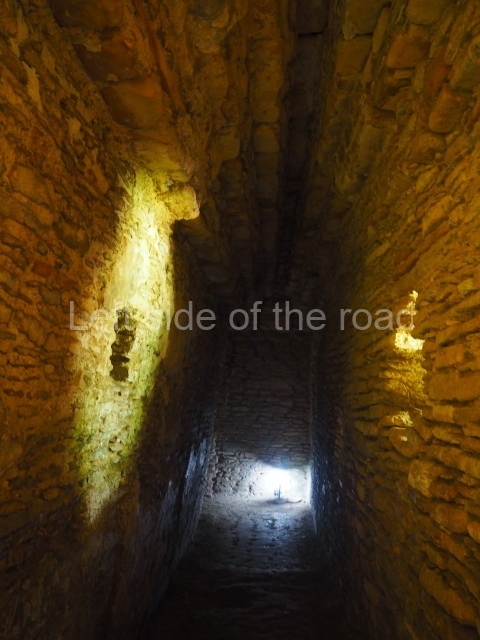

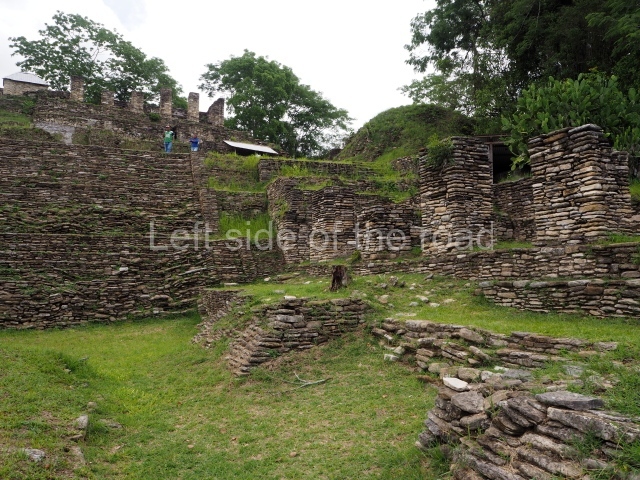

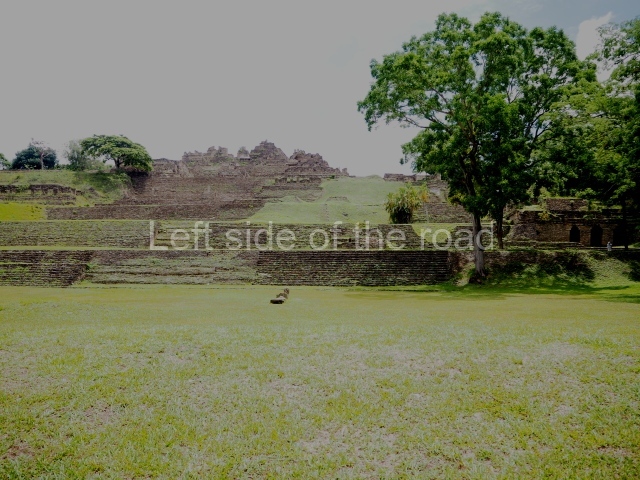

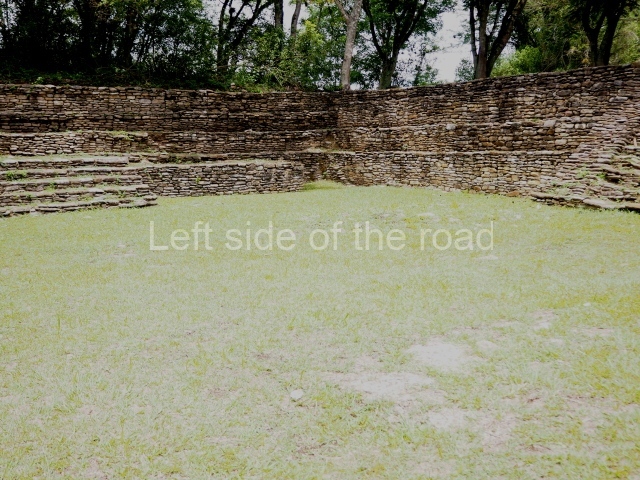

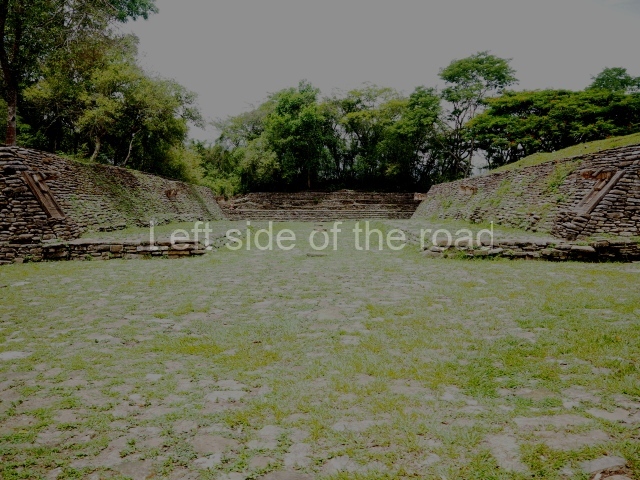

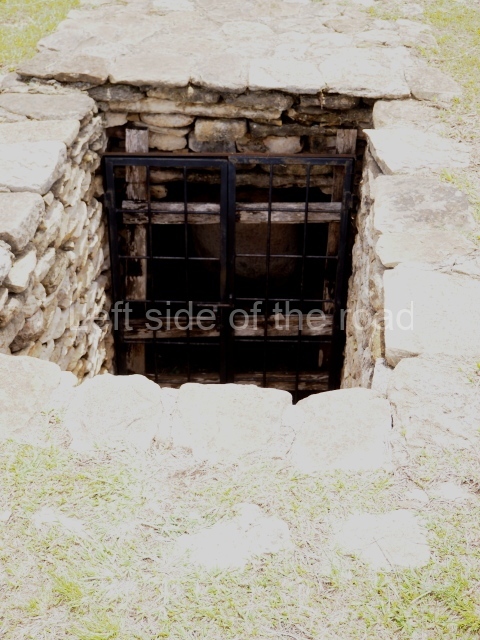

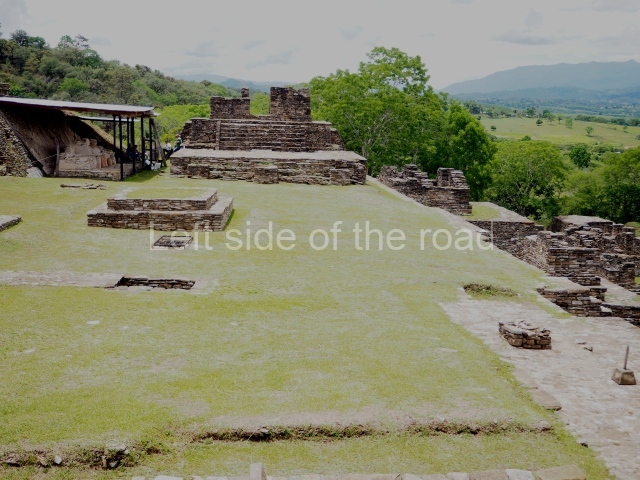

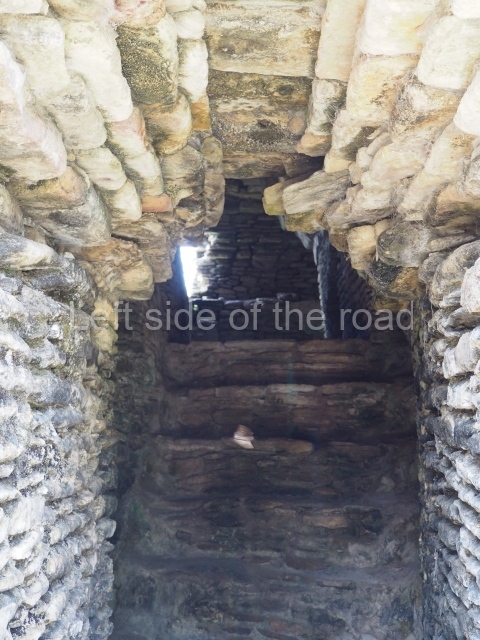

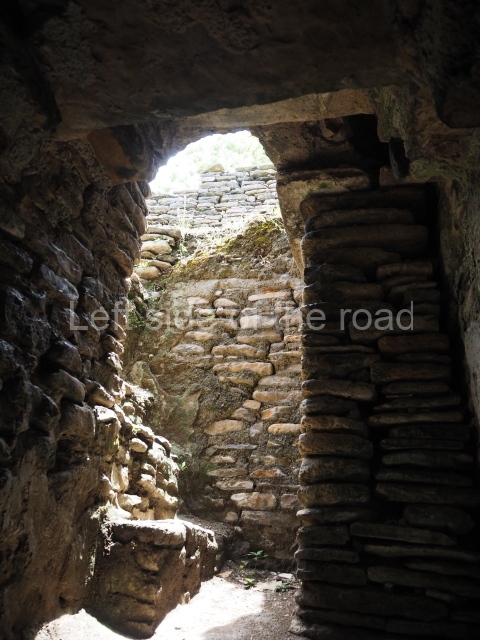

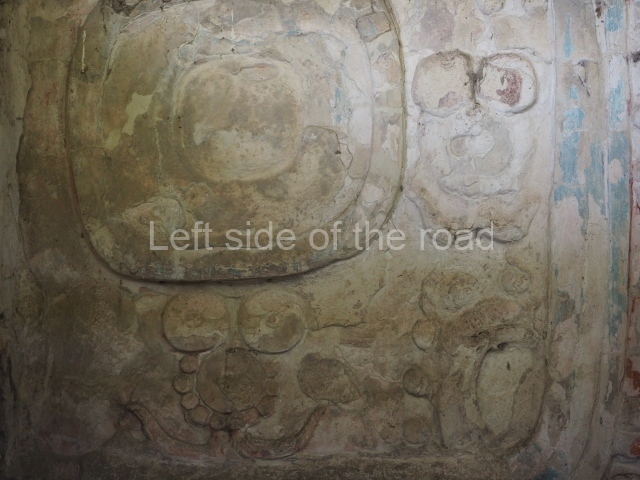

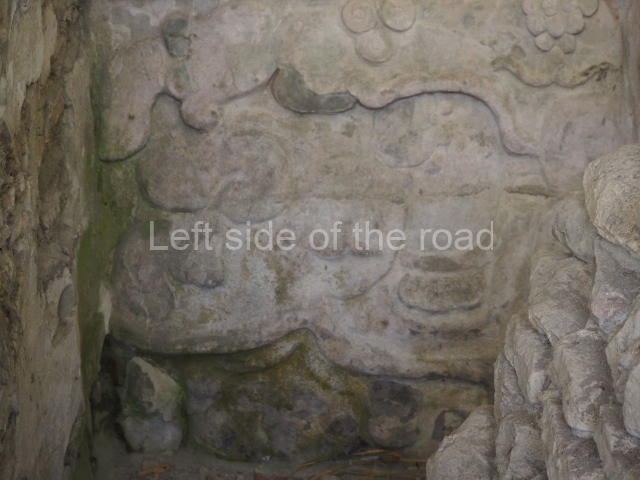

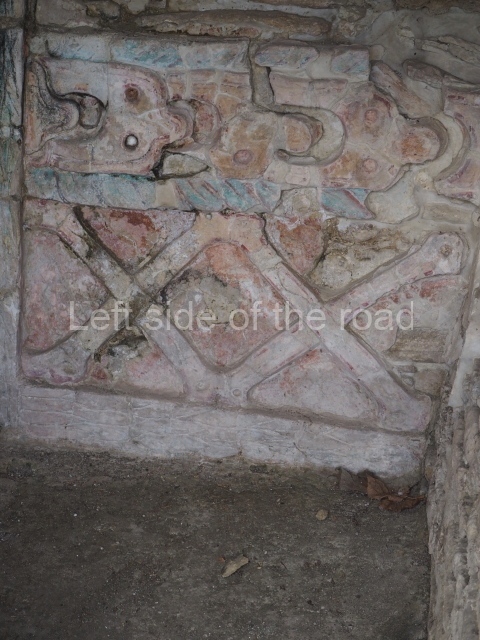

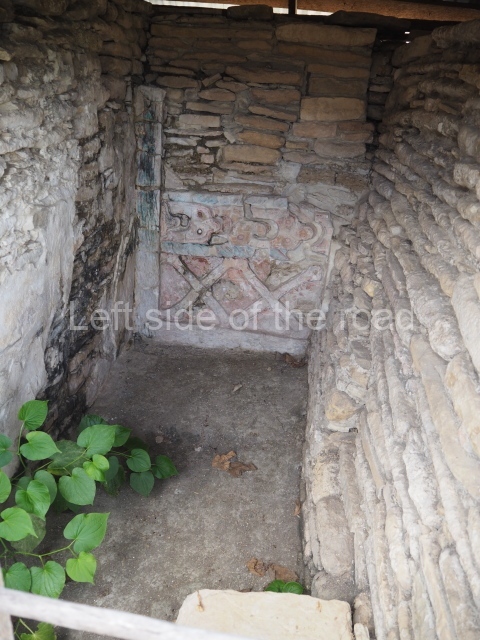

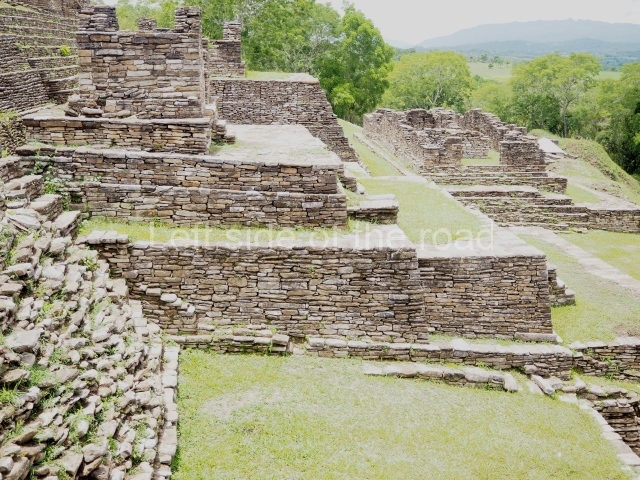

The architectural ruins at El Rey correspond to the Late Postclassic and the East Coast style, and coexisted with the constructions at Tulum, Tancah, Xelha, Xcaret, San Gervasio, Playa del Carmen and even certain buildings at Coba. There are 47 structures at El Rey, which itself covers an area measuring 520 m along the north-south axis and 70 m along the east-west axis. The principal unit or Civic-Ceremonial Precinct is composed of two plazas surrounded by religious constructions comprising temples, altars, adoratoriums and a pyramid platform with architectural evidence of a sub-structure. There are also hypostyle constructions with palatial columns and benches, used as beds, adjoining the interior walls. Situated north of the core area is a 200-m causeway, flanked by residential platforms on which wood and palm dwellings were built. Just south of the core area, three colonnaded temples flank another causeway, this time 300 m in length. Over 500 human burials were found beneath the residential platforms; most show that the humans were buried in a kneeling position. The offerings vary from a simple obsidian or conch knife to ceramic pots and jadeite beads and necklaces. A high ranking dignitary was buried on top of the pyramid platform and the offering associated with this tomb includes a ceramic goblet, two copper tweezers, an arrow shaft made of deer, a conch bracelet and a jadeite necklace. Cranial deformation and dental mutilation can be observed on several skulls, and pathologies such as arthritis and osteoporosis have also been detected, as well as a high degree of vitamin C deficiency. The average lifespan of this population has been estimated at 35 to 40. Like other coastal settlements from this period, El Rey had a texcatl or stone slab for sacrificial use, which confirms that this practice was conducted at the site. The temple known as Structure 3B still contains traces of murals on the interior walls of the vaulted chamber.

Enrique Terrones Gonzalez

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 436-437.

1-6. Structures 1 to 6.

How to get there;

El Rey is located almost towards the end of the long spit of land which houses the so called ‘hotel’ district of Cancun. It’s to be found just over a kilometre after the Museo Maya de Cancun (Cancun Mayan Museum). Buses R1 and R2, to and from downtown Cancun, run regularly along this road. M$12 per journey.

Entrance:

M$70