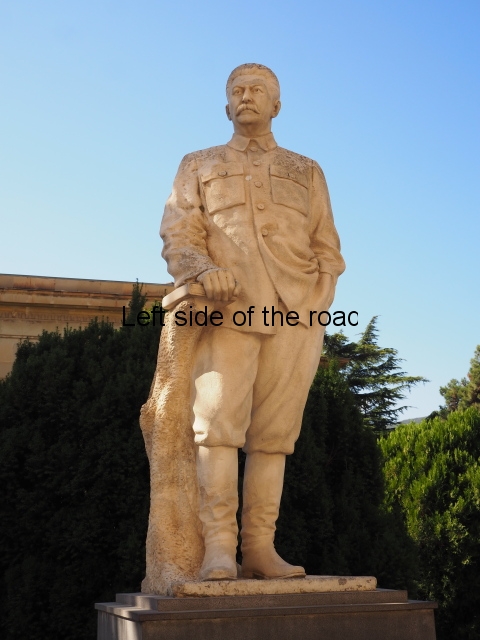

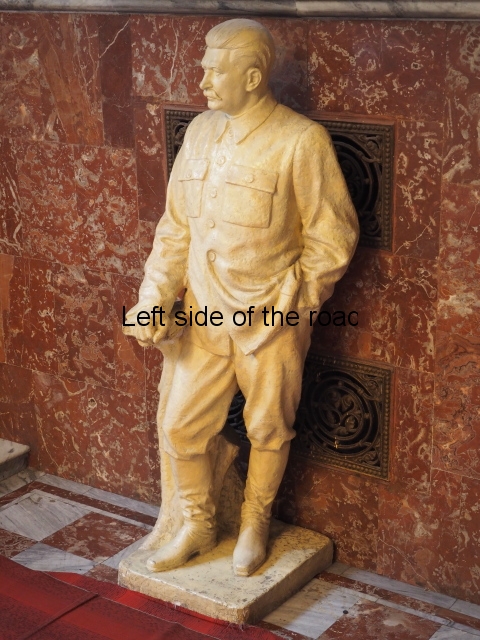

Stalin – outside entrance to Museum

More on the Republic of Georgia

Stalin Museum – Gori

The Stalin Museum in his birthplace of Gori, in the centre of Georgia, is one of the few places in the erstwhile Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) where you will see any reference (let alone a positive reference) to the leader of the world’s first socialist state.

(Before the success of reaction in the Soviet Union, in the 1990s, there used to be a much larger museum dedicated to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, just off Red Square, in Moscow. This was called The Central Lenin Museum. That museum space is now devoted to the successful war against the Napoleonic invasion of 1812 – by ignoring their Soviet past the Russian people have had to go back more than 200 years before they can hold their heads high.)

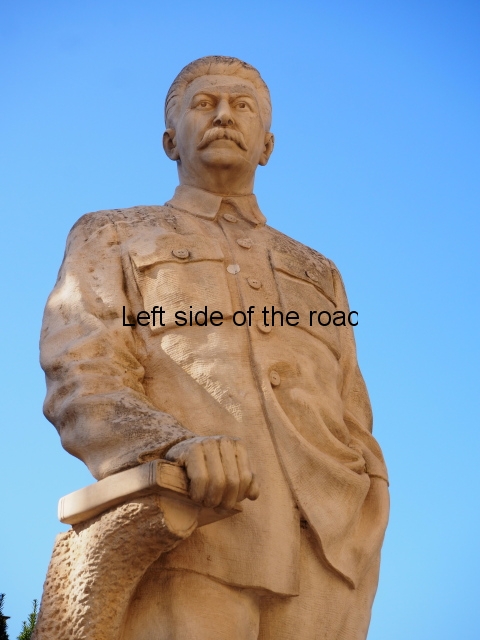

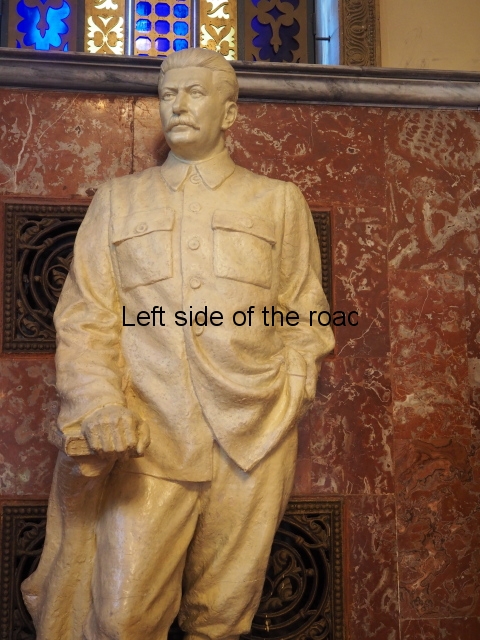

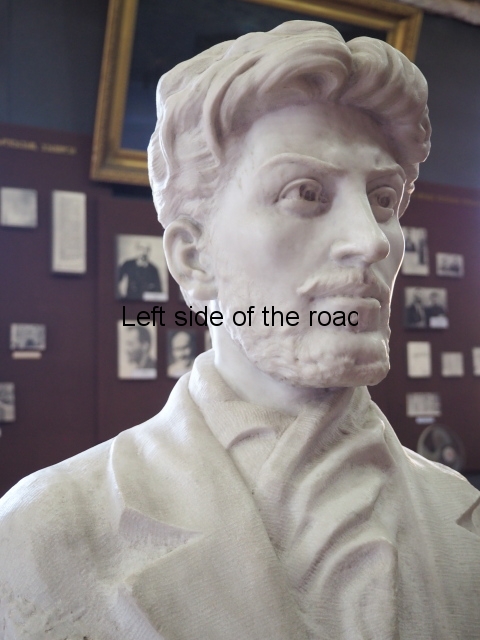

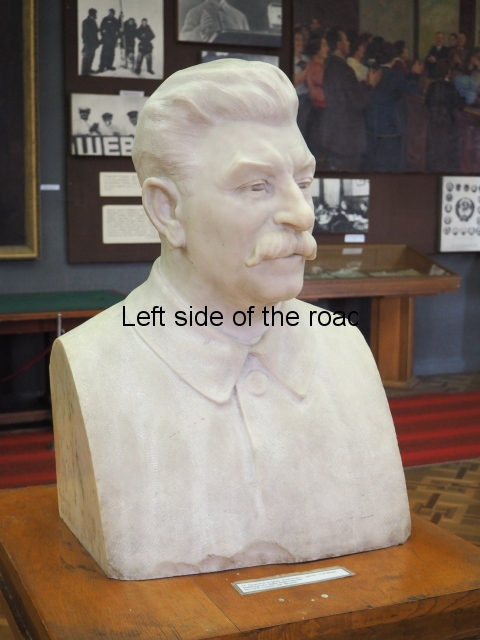

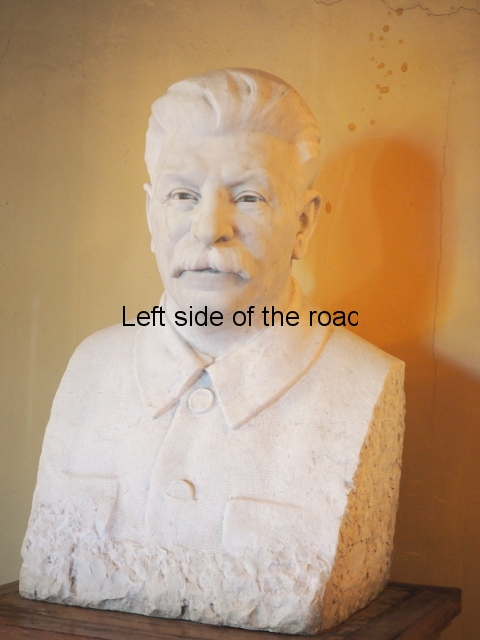

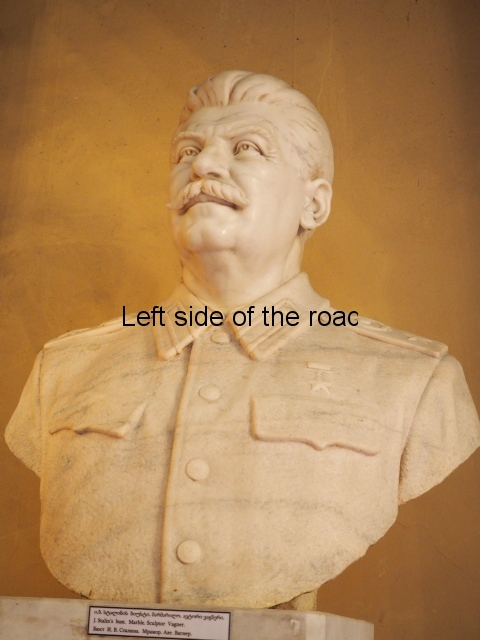

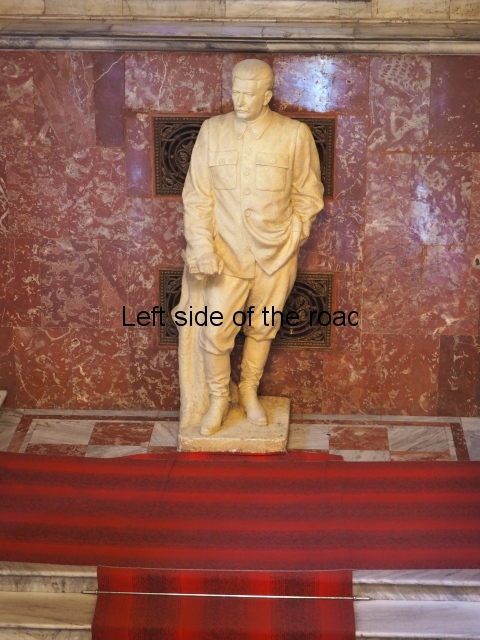

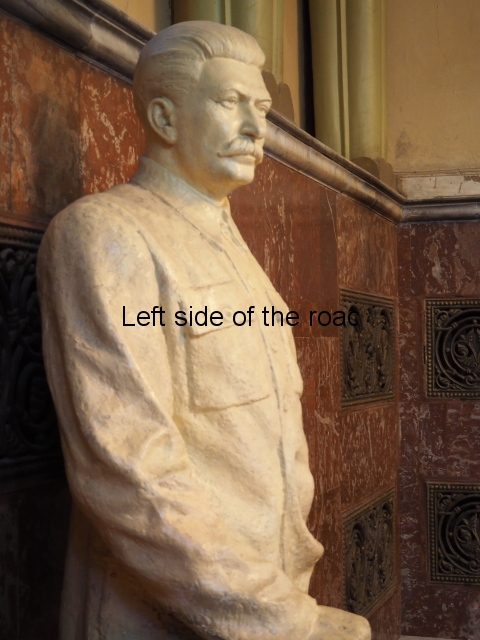

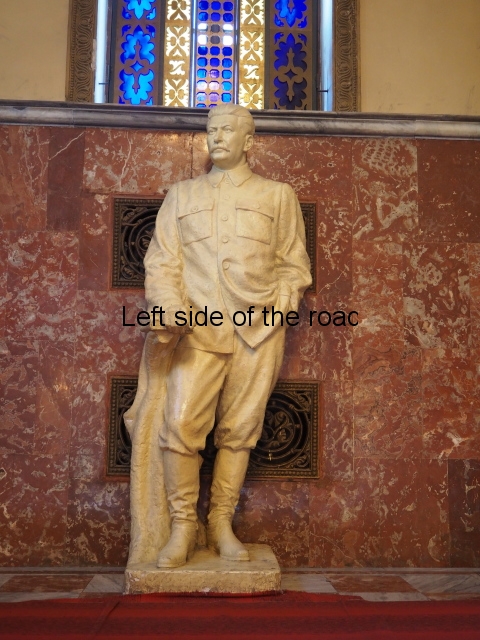

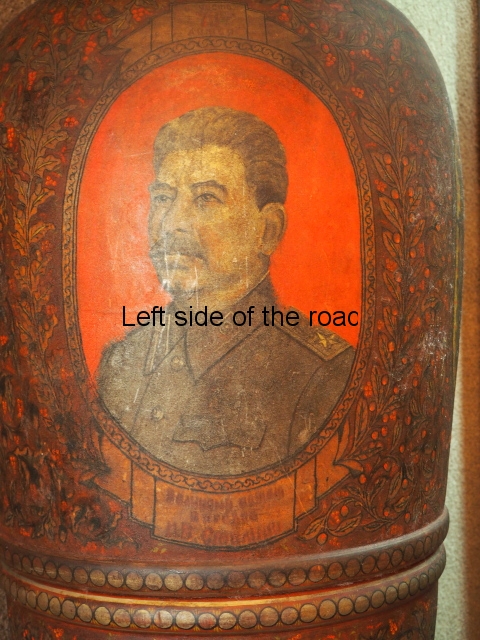

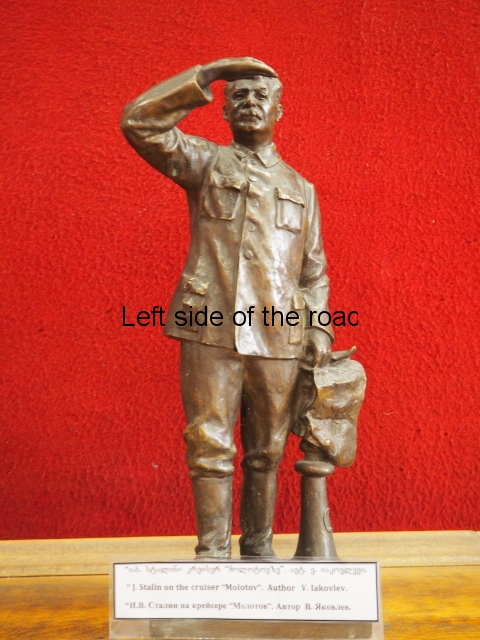

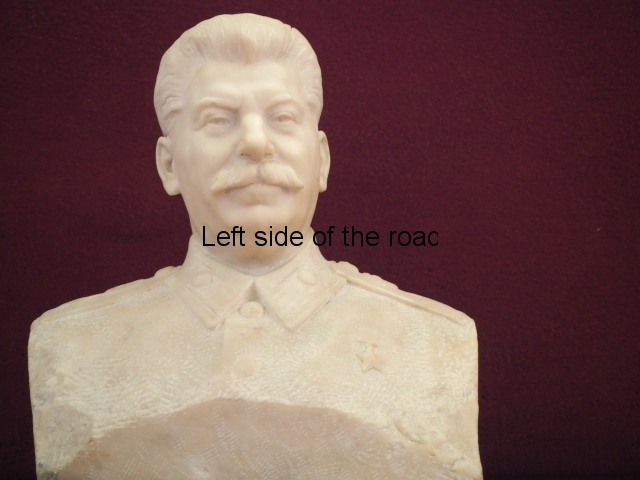

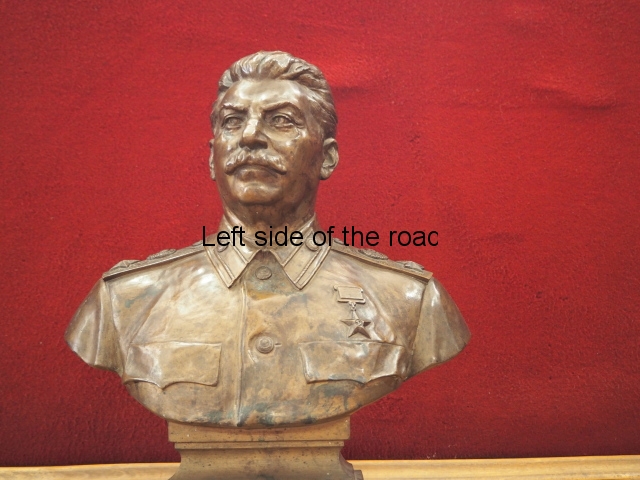

I don’t know when they were created but the life-size Stalin statues – one outside the museum and the copy which stands on the first landing of the stairs to the exhibition halls – are probably some of the worst likenesses of JV Stalin to be seen – apart from the terracotta wine container I obtained in Tbilisi. This, I can only assume, is deliberate. Georgian sculptors are no less able than those in different parts of the world to re-create an accurate image of an individual. To not do so is not a matter of artistic incompetence but a political statement attempting to erase the past.

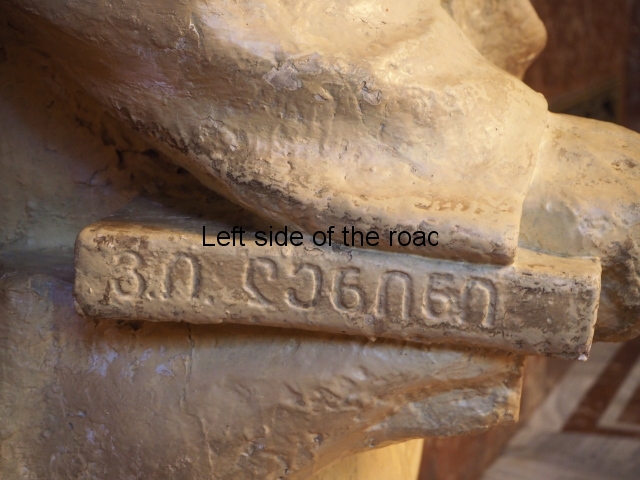

And one thing that demonstrates the dis-ingenuousness of these statues is the fact that Stalin’s right hand is resting on a book of his own writings, with his name in Georgian script on the spine. Never in his lifetime would Stalin self-reference in such a manner. If his hand would be on a book it would have been either on one of Marx, Engels or Lenin – never himself.

(However, though not widely known by visitors or really publicised anywhere in Gori itself, there are two ‘proper’ and ‘realistic’ statues of Uncle Joe still in existence within the city.)

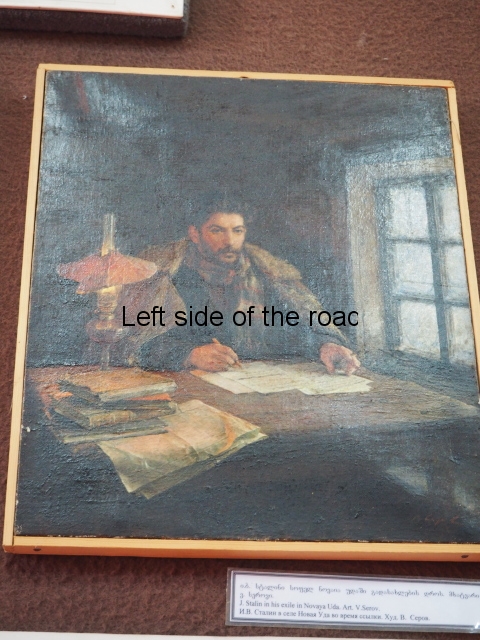

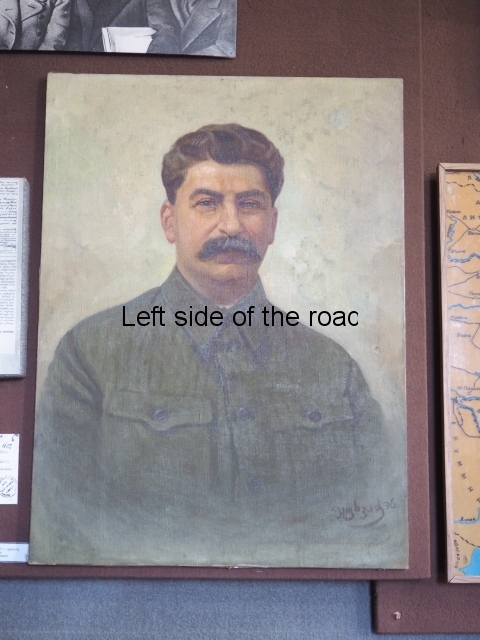

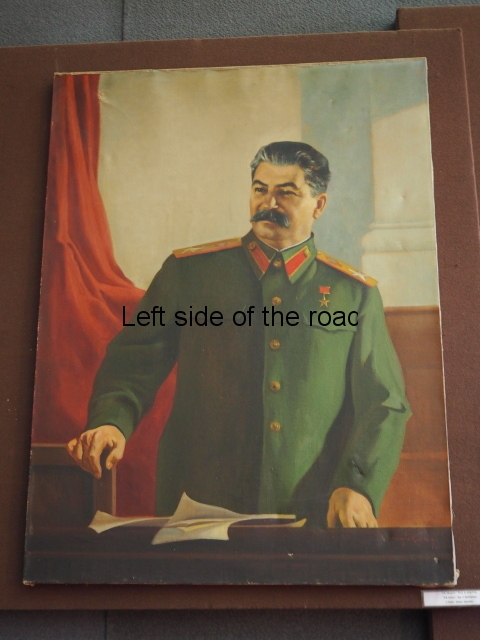

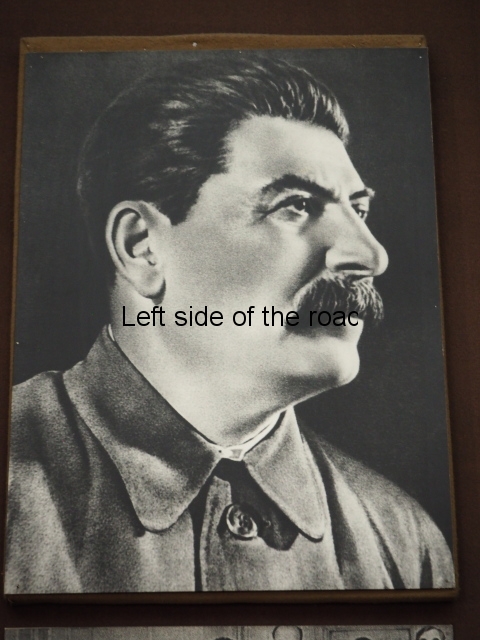

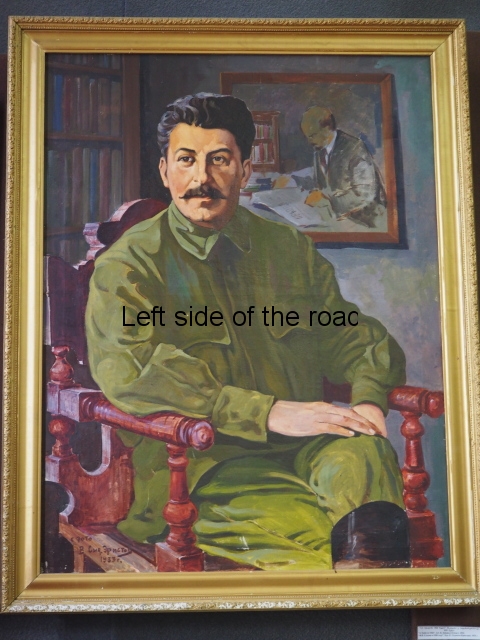

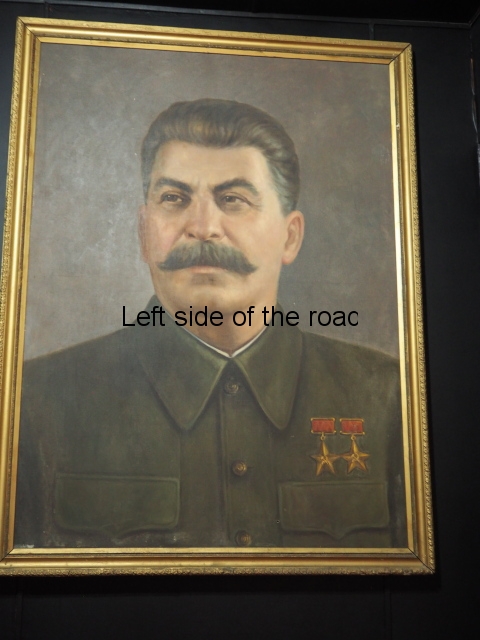

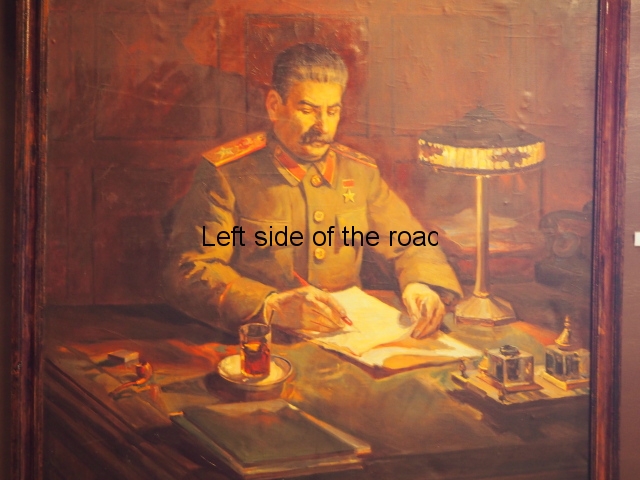

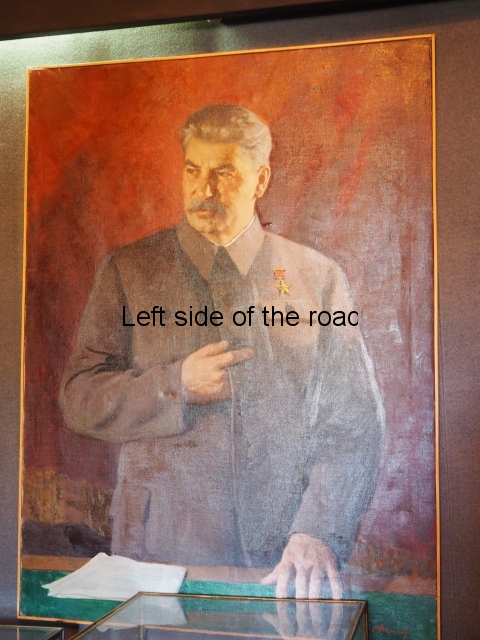

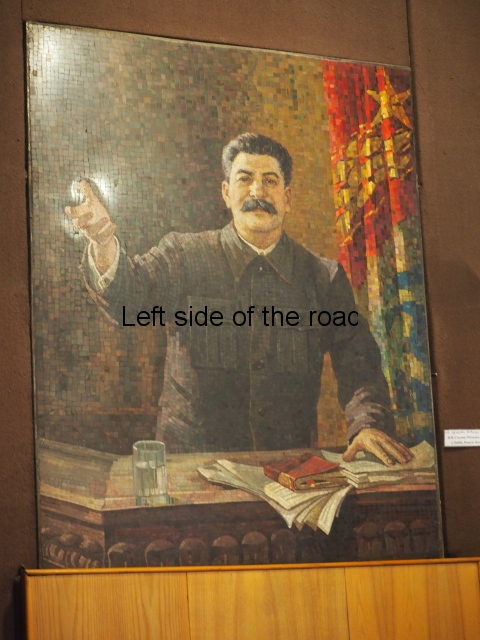

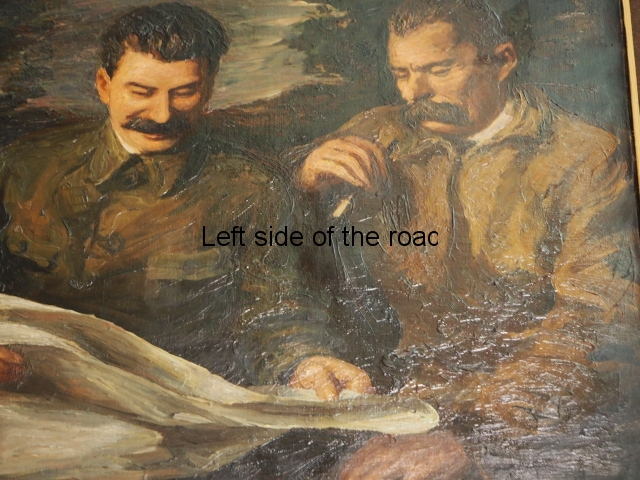

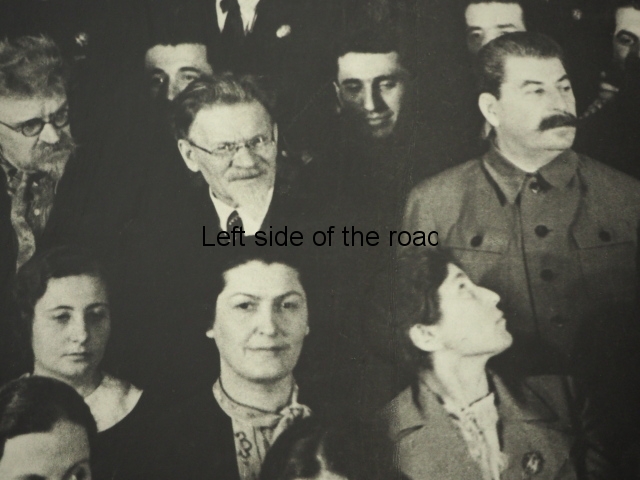

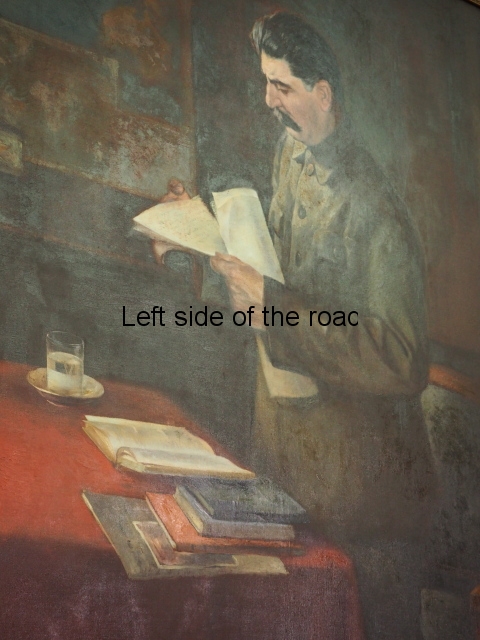

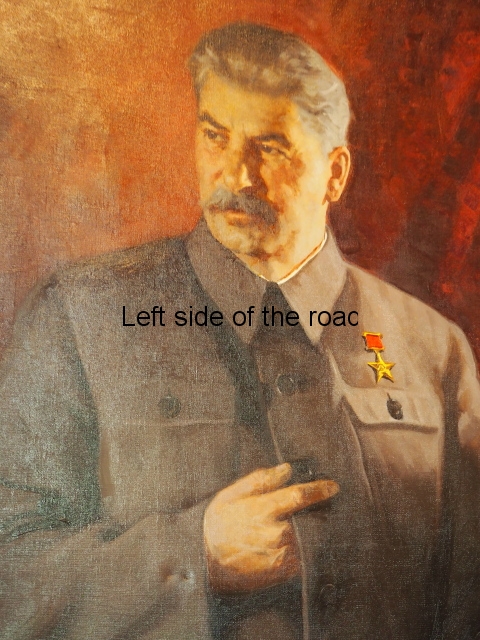

Comprising mainly of artistic representations of Stalin’s life (paintings and statues) and reproductions of photographs – many of which anyone with an interest in the period would have seen before – there are also a few personal artefacts. Uncle Joe wasn’t really into ‘consumerism’ and so there are few of the latter.

The aim of this post is to provide a video and photographic impression of the museum for those who have not yet had the opportunity to visit this unique location. To go to a video of the various parts of the museum click the link on the individual Rooms (numbered from 1 to 6, plus the Illegal printing press in Tiflis (Tbilisi), the reconstructed Kremlin Office and Stalin’s Birthplace). (Apologies for the low quality of the videos – no Oscar for me this year.) Then there’s a quite extensive photographic slide show/gallery at the end of the post.

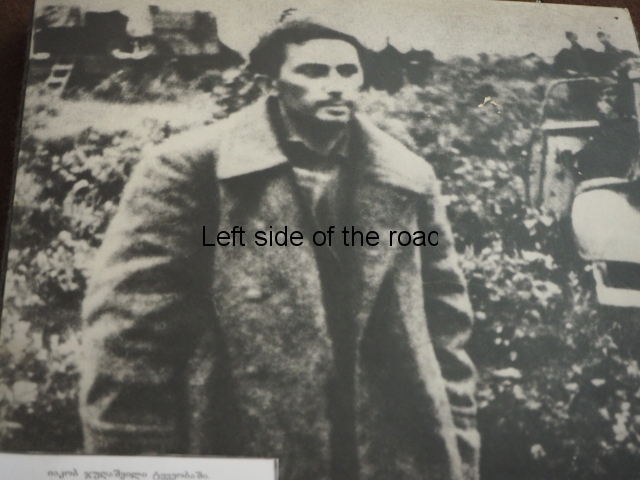

Young Stalin

Room 1 – Early life, through Revolution and Civil War to the death of VI Lenin

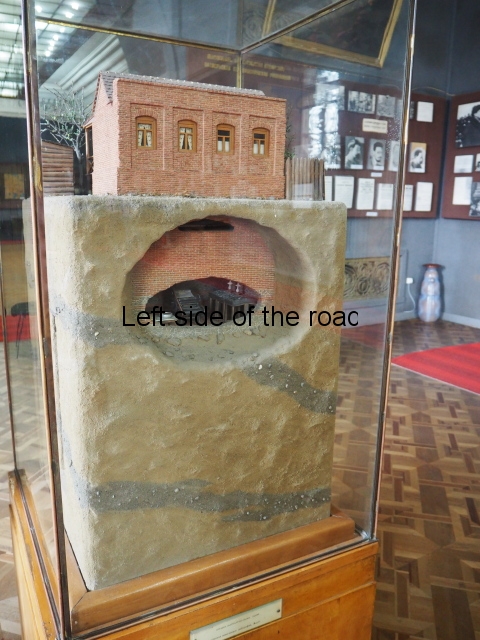

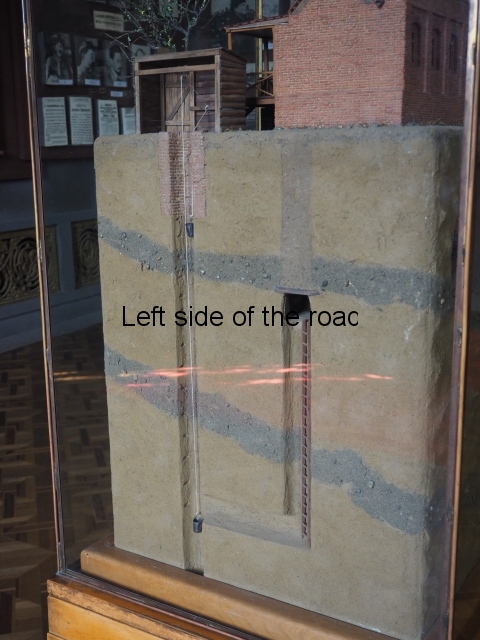

Highlights of this room include: a full size statue of the young Stalin; a maquette of his birthplace; a bust of the young Stalin and a maquette of the illegal printing press (see below).

The house of the illegal printing press, Tiflis

The illegal printing press in Tiflis (Tbilisi) 1906

Just before the entrance to the second room, in the middle of the floor, can be found a maquette of the building which hosted the illegal printing press that Stalin was instrumental in establishing (and for which he wrote many articles and leaflets) that existed for a short time from November 1903 to April 1906 in Tiflis (present day Tbilisi). From looking at this model you can appreciate the amount of effort and planning that went into the hiding of this press from the Tsarist reactionary forces (and especially its ‘secret’ police, the Okhrana). It also makes you think about the determination of the Georgian/Russian revolutionaries to defeat the exploiting class. Such imagination, determination and dedication of present day ‘revolutionaries’ would be more than welcomed.

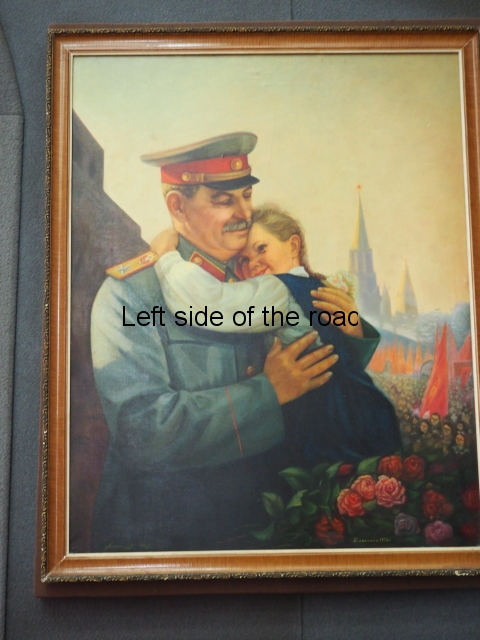

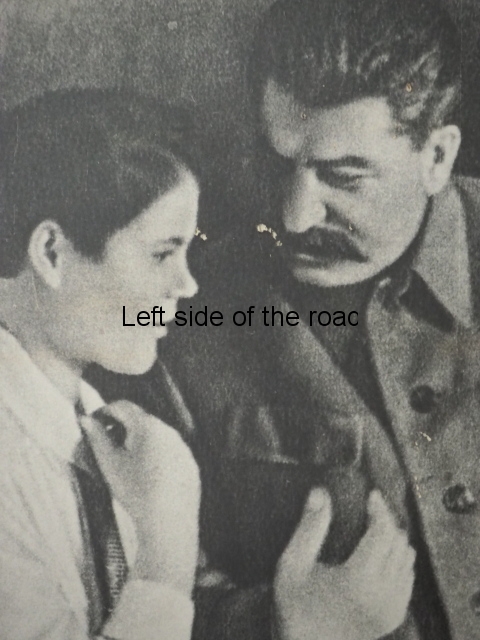

Stalin with the future

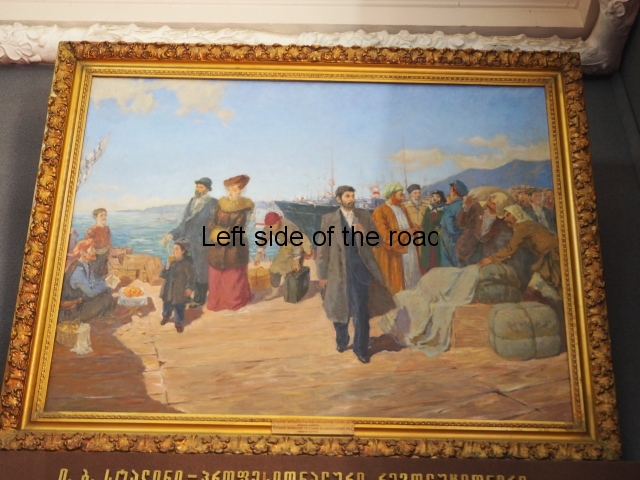

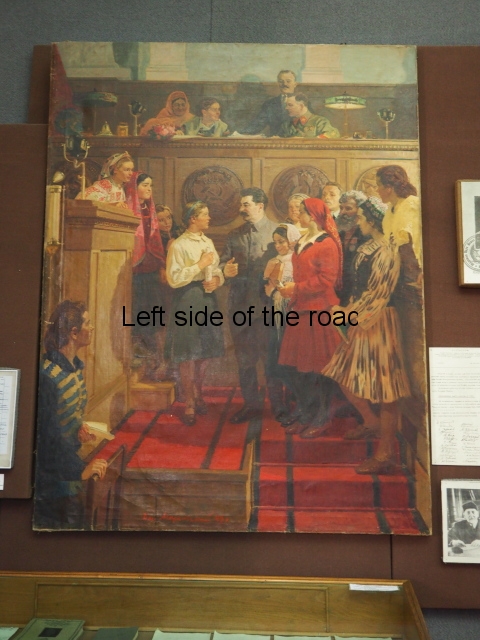

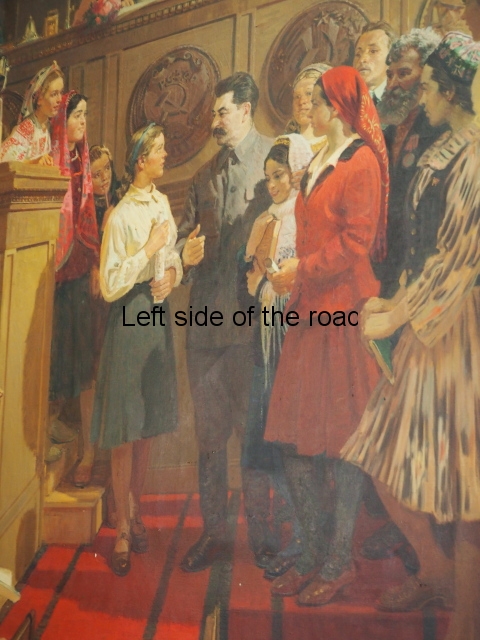

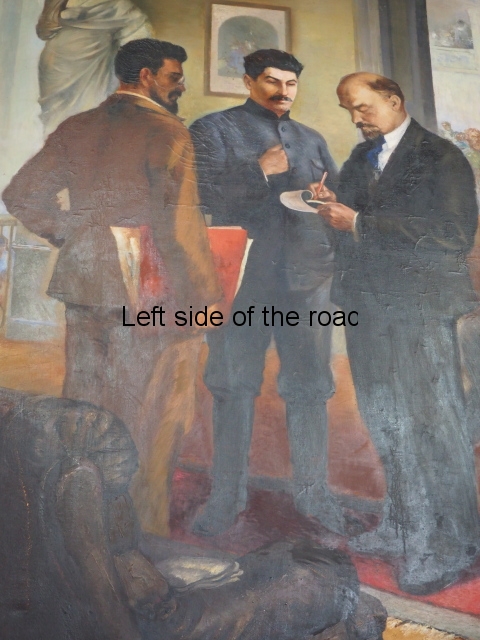

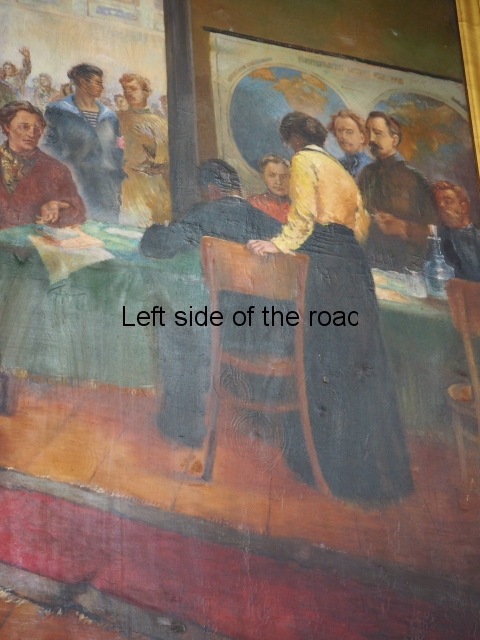

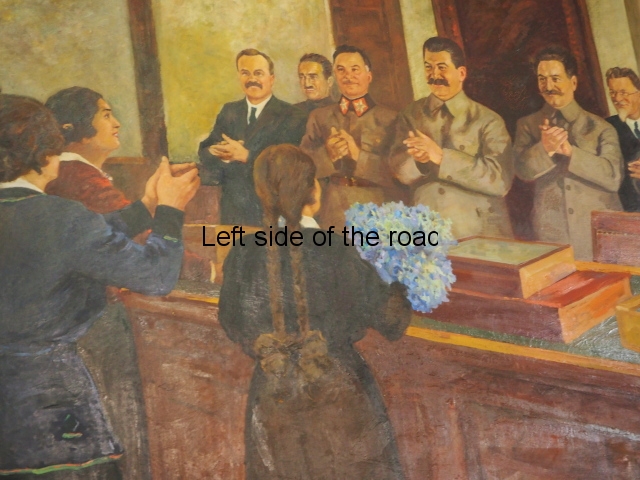

Room 2 – From Collectivisation and Industrialisation to the beginning of the Great Patriotic War

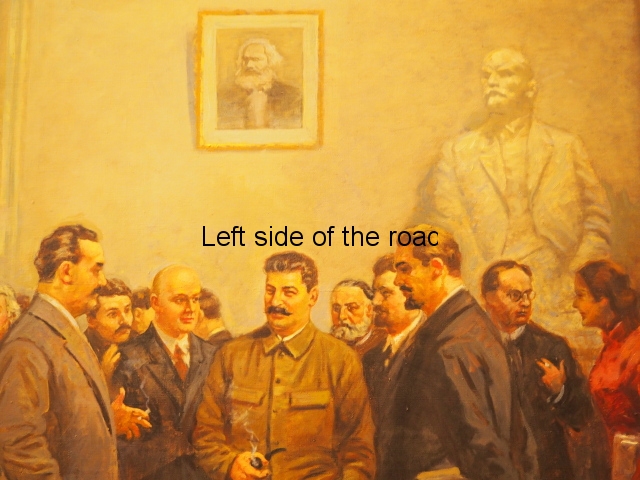

Highlights in this room include: Stalin at a meeting with workers in a locomotive works; Stalin with Collective Farm workers; Stalin greeting a young female collective farm worker; a series of postcards produced in the 1930s and a large bust of an older Stalin.

Stalin tank lamp

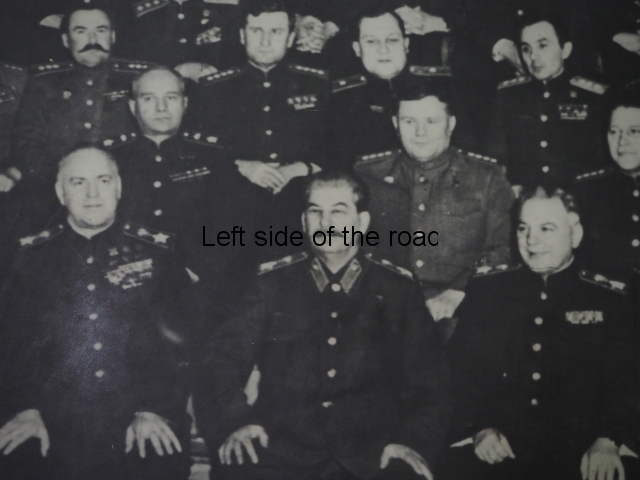

Room 3 – The Great Patriotic War

Highlights in this room include: a lamp incorporating a Stalin tank; a section on Stalin’s family (his wives and children); military maps describing some of the major campaigns of the Great Patriotic War and Stalin with his generals.

Soviet power annihilates Nazism

Room 4 – A review of his life and the 19th (final) Congress

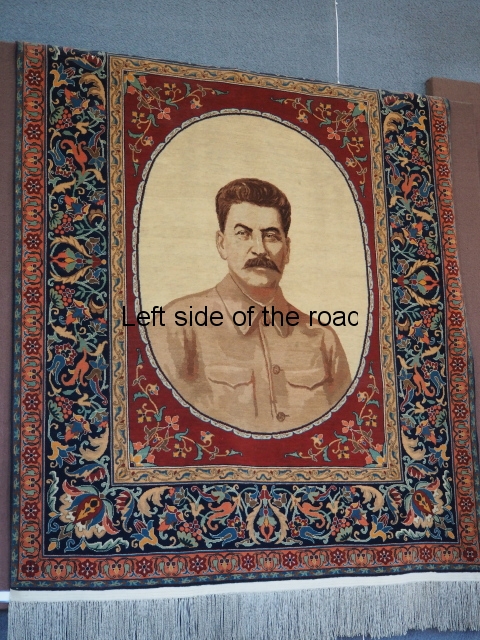

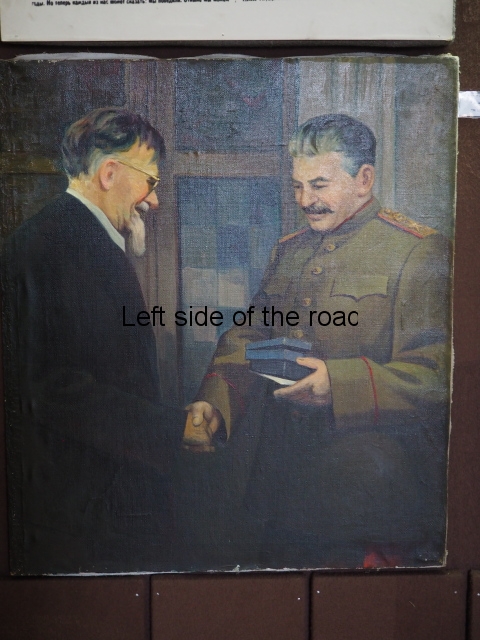

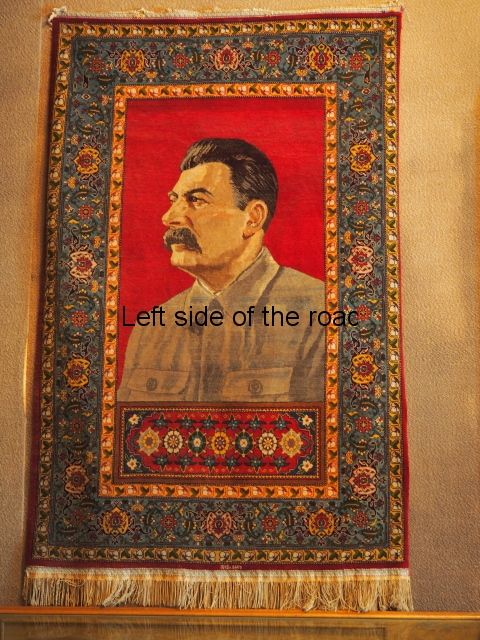

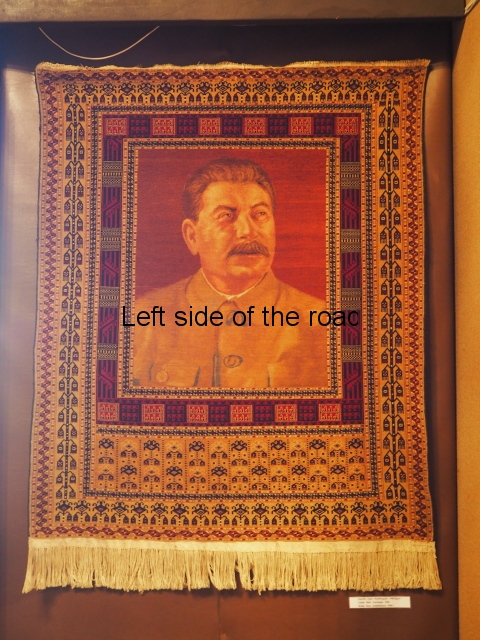

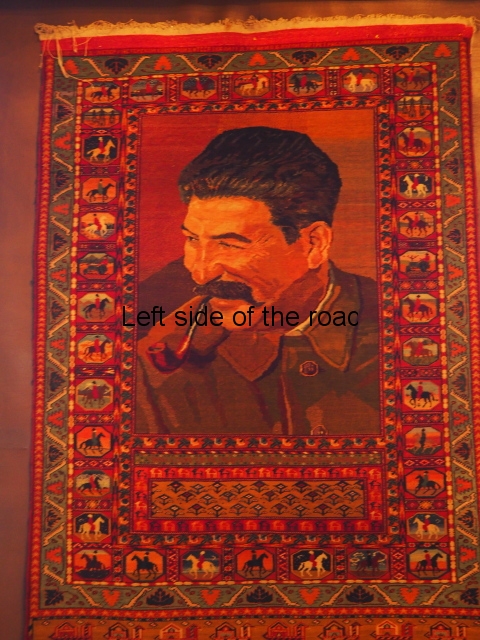

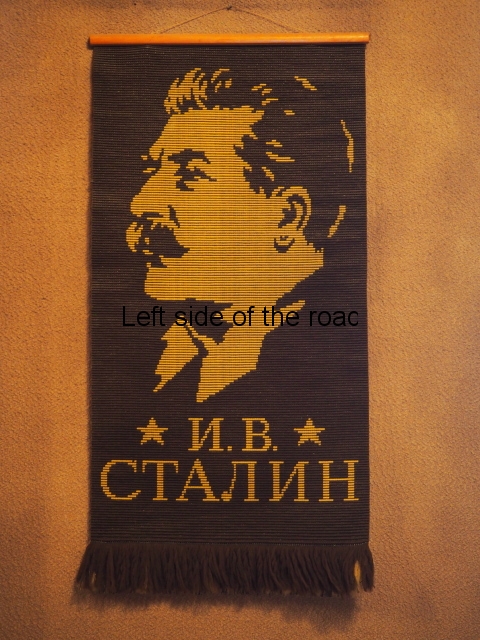

Highlights in this room include: a carved wooden shield with Stalin in profile amongst a number of symbols representing the Soviet Union and the image of a Russian sword smashing through a swastika at the bottom right; pictures taken a various stages of Stalin’s life; two large carpets with an image of Stalin (one of them also with Kliment Voroshilov); an image of Nazi banners being dragged through the dirt of Red Square in front of the Lenin Mausoleum and a picture of one of Stalin’s last public appearances at the 19th Congress of the CPSU.

Stalin lying in state – 1953

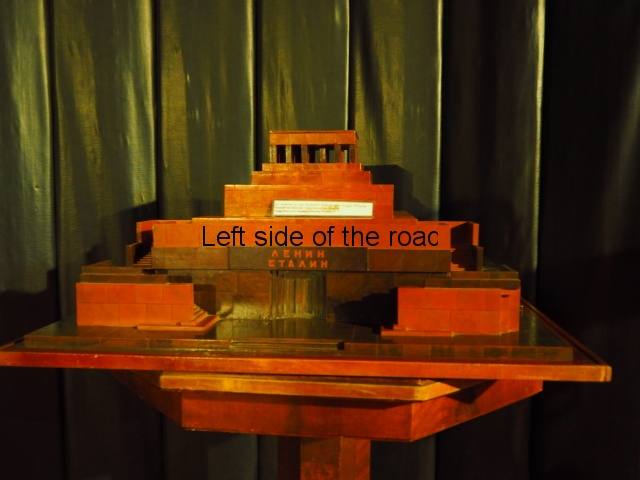

Room 5 – Stalin’s Death

Highlights in this room are: Stalin’s death mask; a painting of Stalin lying in state and a maquette of the Mausoleum in Red Square bearing the names of both Lenin and Stalin.

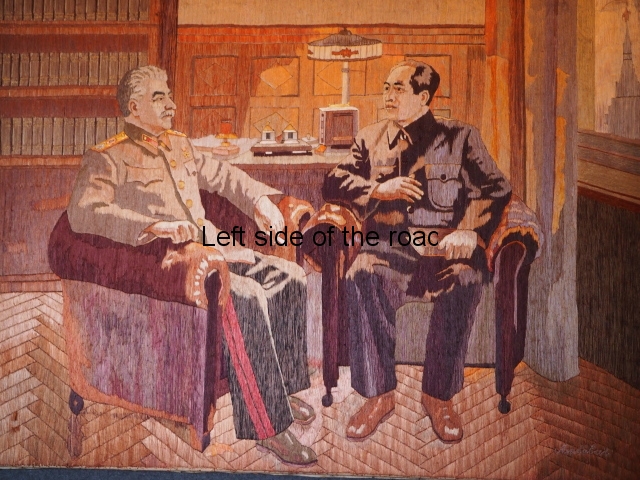

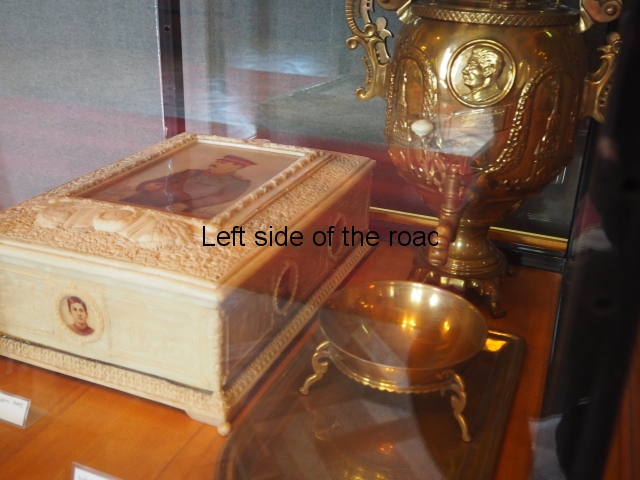

Stalin and Mao

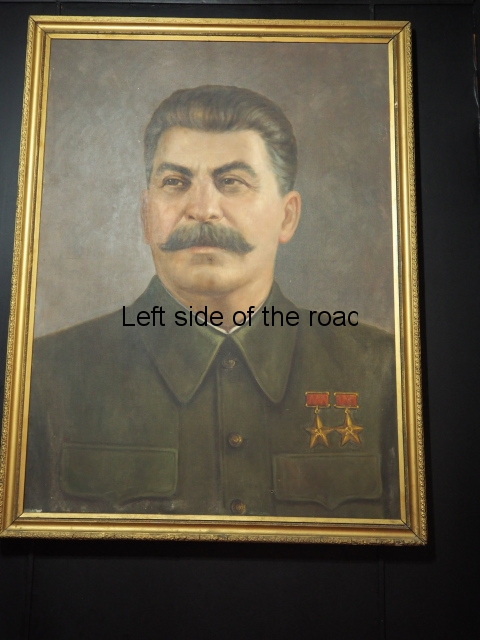

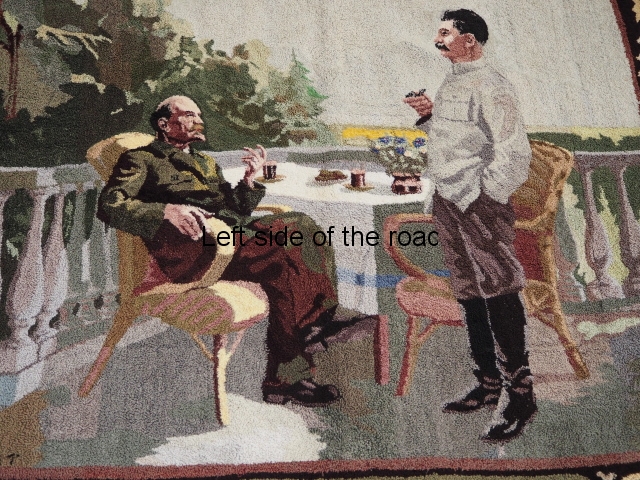

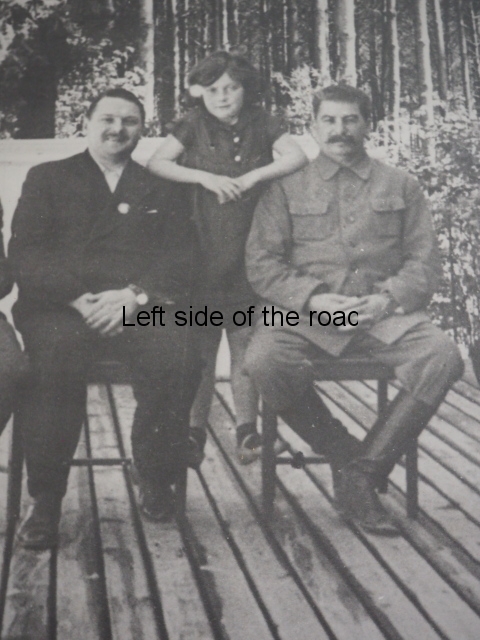

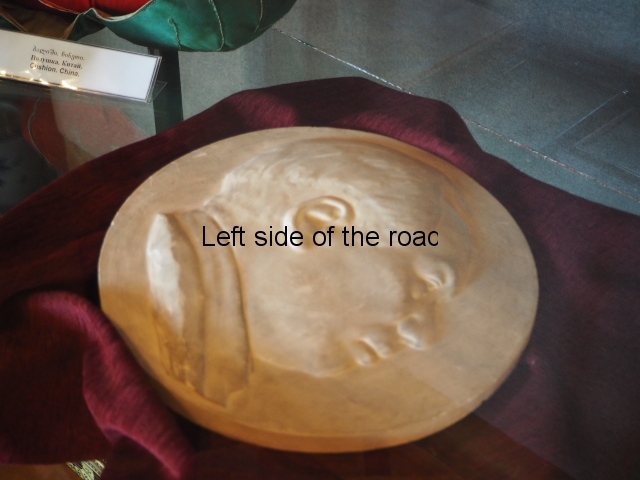

Room 6 – Presents

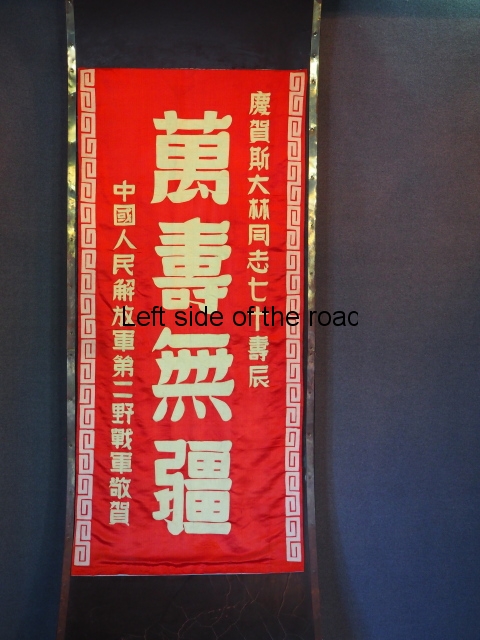

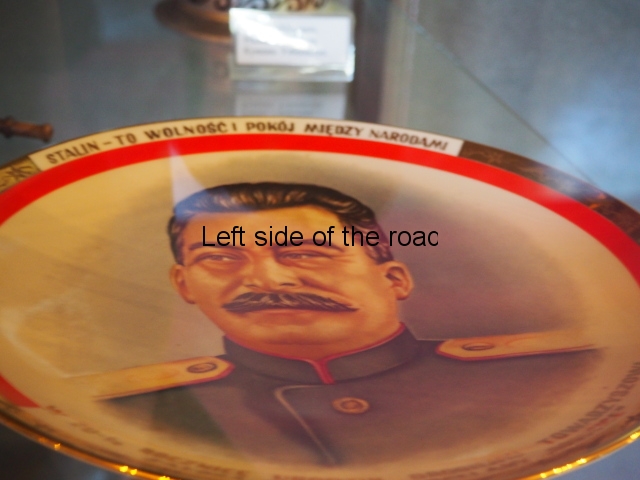

It’s in this room where there are more artefacts and this consists of presents and other objects bearing the image of Stalin, of other Communist leaders and items brought from former Socialist countries representing their culture. There are many objects (many depicted in the slide show) but it’s worth mentioning a picture of Stalin and his daughter, Svetlana, as a young girl; a textile print of a meeting between Stalin and Chairman Mao Tse-tung; a number of large carpets with Stalin as the central image; a couple of images of Stalin with his mother; a large, Chinese silk portrait of Stalin and a large, circular, metal plate with a mosaic of Stalin in the centre.

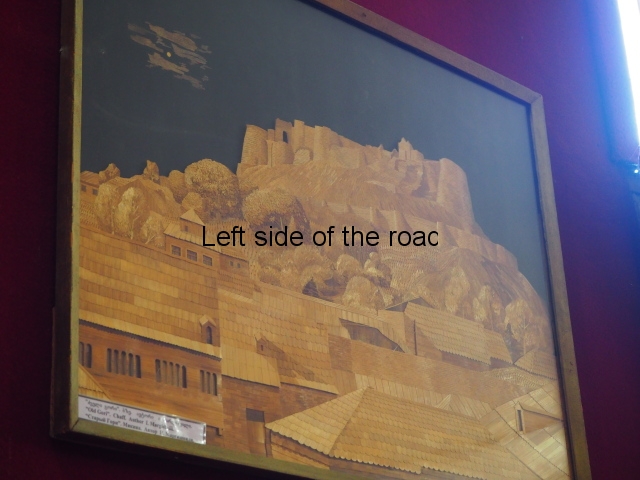

Stalin’s office in the Kremlin

Stalin’s Kremlin Office Reconstruction

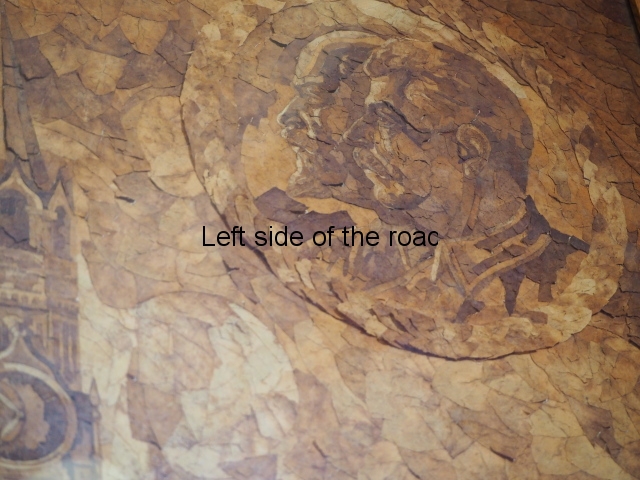

On leaving the first floor, where the majority of the exhibits will be found, by taking the right hand staircase this will lead you to the reconstruction of Stalin’s Kremlin Office (the first door on the right). Really the office is just the collection of chairs and sofas with a desk immediately on the right as you walk through the door. The rest of the space is taken up with further images of Stalin, both in paint and intricate marquetry; one of his ceremonial uniforms; two maquettes of the Stalingrad War Memorial and (quite unique) an image of both Lenin and Stalin made from tobacco leaves (just above the piano).

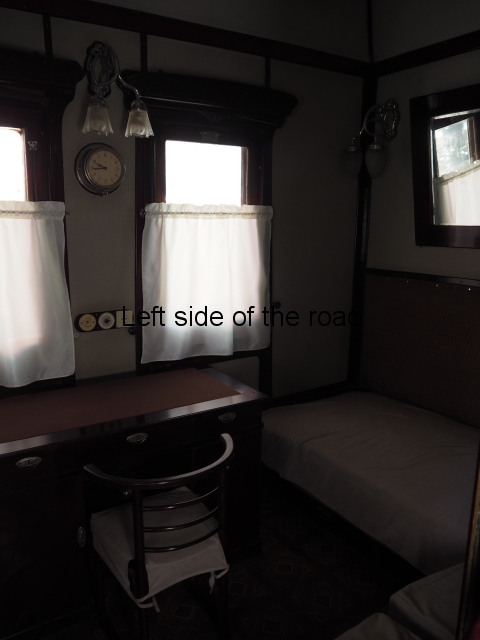

Stalin’s armoured carriage

Stalin’s Armoured train carriage

Outside the museum, to the left of the building, is Stalin’s armoured carriage. He didn’t like to fly and travelled to the major conferences with the US and UK ‘allies’ at Tehran, Yalta and Potsdam in this carriage. This can be visited as part of the general ticket to visit the museum.

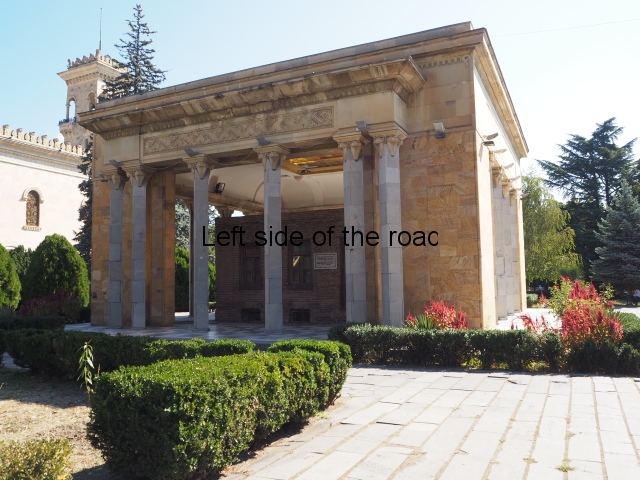

Stalin’s Birthplace, Gori

Stalin’s Birthplace

The humble building in which Stalin was born is almost unrecognisable now. Although restored to an almost new condition the two room building – of which on the tour you only see one – has been surrounded by a grand and almost temple like Doric structure. This is topped by a glass dome on which is a magnificent star and in each corner there’s a hammer and sickle symbol. This was erected in 1939. This is lit up at night and looks quite impressive with the various light temperatures, giving off a golden and green glow at the same time.

Related;

Rediscovered statues of Joseph Stalin

The Great Patriotic War Museum and War Memorial

Practicalities

Location

The Museum, Stalin’s Birthplace and the railway carriage take up what is the top of an inverted triangle of Stalin Park, with Stalin Avenue on either side and Kutaisi at the top. It’s right in the centre of town and not difficult to find.

Opening times

1st November – 1st April 10.00-17.00

2nd April – 31st October 10.00-18.00

Closed 1st January and Easter Sunday

Entrance

Visit of exhibition halls, memorial house and Stalin’s Railway Carriage:

General 15 GEL

Students 10 GEL

Schoolchildren 1 GEL

Under six Free

It’s not necessary to take the tour but for that extra bit of information it’s worthwhile. Unfortunately there doesn’t seem to be any set time for the tour but English tours take place quite regularly, at least between April and October. They take about 45 minutes so if you miss a tour my suggestion is that you find out the time of the next tour, more or less, have a walk around the museum and then head back to the entrance of Room 1 at the time the next tour will be starting. The tour takes in both the train carriage and Stalin’s birthplace as well as the museum.

GPS

N 41.98683

E 44.11330

DMS

41° 59′ 12.588” N

44° 6′ 47.88” E

More on the Republic of Georgia