Lavdi Deshmoreve – Glory to the Martyrs – Edison Gjergjo

Evolution of lapidars in Albania – part of the struggle of ideas along the road to Socialism

Introduction

It’s relatively easy to make a revolution – the difficult part is being able to survive the fury of the reaction from capitalism/imperialism and the death and destruction it is prepared to rain on any group of workers and peasants who dare to challenge the established order. If a society survives that onslaught – and many have not – then the building of the of a new, Socialist, classless based society is even more difficult. Of the few workers and peasants revolutions that were successful in the 20th century it’s worth mentioning from the start that they were all led by organised Communist parties which followed, and developed, the Marxist-Leninist ideology – thereby putting the Trotskyites, the Anarchists and any other ‘ideology’ in their place.

It’s also relatively easy to re-organise industry and agriculture in a different, collective manner from that which has existed since the early years of the 19th century. The term ‘relatively’ has to be taken in context. Industrialisation and collectivisation in the Soviet Union, for example, from the late 1920s into the 19030s, wasn’t easy and was fraught with difficulties. But the first step – taking the land and the means of production away from the big landowners and capitalists – was achieved by the organised workers (and especially their leadership) who knew force of arms, used by the majority of the population, was a winning argument.

However, the biggest hurdle a new workers’ state has to face in the effort to construct Socialism, the biggest challenge that has to be taken on and the issue that has to be resolved before a truly new society can be established is in the confronting the ideas of the old society which are entrenched within all who have been brought up in a society relying on oppression and exploitation. Some willingly confront these vestiges of the past, some do so reluctantly, some cling on to them in the hope the new social ‘experiment’ will fail but all within the new Socialist society have to take a stance on this matter – whether they are aware of it or not.

Not only do we need to put capitalism and imperialism into the dustbin of history, to the same wheelie bin we also have to consign the old ideas.

And that’s not easy.

In fact it’s so difficult that no society which has attempted to build Socialism has been able to exist for more than 46 years – barely two generations – but even that was a major achievement when we consider that the country in question was Albania which had a tiny population and was faced, from the very beginning, with the open hostility of the capitalist and imperialist forces who came out of the Second World War weakened (especially in Europe) but still hell bent on destroying those societies that had taken up the Red Banner of Socialism. Whilst overcoming those early attempts at the restoration of capitalism Albania later had to face the chaos, both economically and politically, caused by the revisionist degeneration of once proud Communist, Marxist-Leninist Parties.

In this article I want to look at how the Party of Labour of Albania, under the leadership of Enver Hoxha, sought to use culture, especially those monuments, mosaics and bas reliefs (known as lapidars in Albania) which were on permanent public display throughout the country, as a weapon in the idealogical battle against the old ideas of the rotten and moribund capitalist system as well as counter-acting the ‘new’ ideas of the equally rotten ‘modern revisionism’ which was aiming to destroy the Socialist state from within.

What is a lapidar?

The simplest English translation of the Albania word ‘lapidar’ would be ‘monolith’. It may also be useful to say it’s a word used to represent monuments in Albania long before the victory of the Communist Partisans in the National Liberation War on November 29th 1944. It is also true the vast majority of lapidars created after liberation were in fact simple monoliths which were often erected in locations where there had been a battle with the fascists – first Italian and then German – and where Partisans had been killed and buried (often hurriedly) in the vicinity.

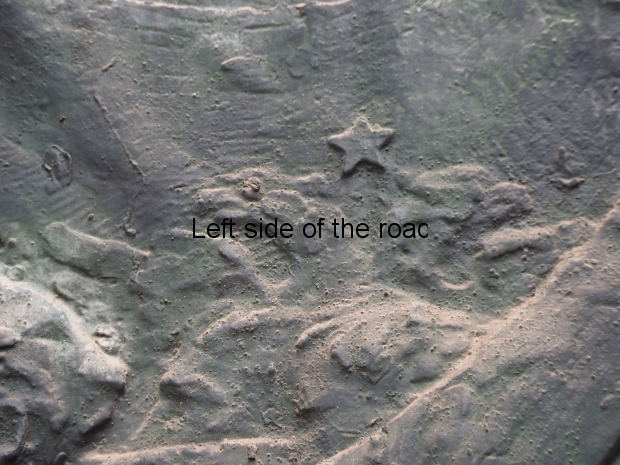

They were normally a four sided pillar with the sides tapering as it got higher but which were truncated long before arriving at a point. These vary in size from ones just over a metre high to ones slightly more elaborate and 5 or 6 metres high. Normally there would be a plaque attached with the names of the Fallen and often a Red Star at the top indicating these were Communist Partisans. (As you will see later these red stars were like a red rag to the reactionary and fascist bulls after the restoration of capitalism in Albania in 1990.)

But as the revolution and the construction of Socialism in Albania developed, as the issues the country had to face became more difficult and complex, so did the lapidars evolve to encompass more statuary and architectural elements.

To get a visual idea of this evolution in Albanian lapidars it would be useful to have a look at a short film, called ‘Lapidari’ (Director: Esat Ibro, Screenplay: Viktor Gjika, 1984–6) which shows the evolution of a single lapidar in the countryside. From being a simple grave it evolves into a more elaborate structure as the society becomes more wealthy so that at the end it is faced with marble slabs.

There are a couple of interesting touches in this short video which put matters into its historical context. One is the capture of renegades who had attempted to subvert the society with the assistance of the imperialist nations, particularly the British. This is the scene where we hear aircraft noises at night and then the capture of these traitors. As they are led away in handcuffs the villagers surround the lapidar in a symbolic move of protecting what had been fought for in the past.

This lapidar sits in the middle of the community and ‘observes’ the changes that take place over the years with the collectivisation of the land, which brings with it machinery and at the very end we see an image of an electricity pylon which indicates the electrification of the country. Being at the centre of the community it also is the focal point for public holidays and this was an aspect of all the lapidars in the country, in the cities as well as the countryside, where children would play an integral part of the celebrations.

Pioneers stand as guard of honour on Martyrs’ Day May 5th

Children would lay flowers on the lapidars and stand guard at the tombs in the larger cemeteries on those national occasions. This was in an effort to educate children about the past, where their family members had fought against the invading fascists and had provided for the first time in Albania’s history a true liberation for the working people reinforcing the connection between the present and the past.

The Albanian Lapidar Survey

I first became aware of the lapidars on my first visit to Albania, in 2011, when I travelled extensively around the country encountering some of these remarkable structures from the window of a bus or a train. Once I realised what a treasure trove there was of these monuments I decided I would start a project to make a photographic record of these unique structures as the amount of deliberate vandalism I was seeing, together with general neglect indicated they would soon disappear from the landscape. The problem was there were only so many I could visit just based on chance encounters as I went around the country.

In Tirana I met, by chance, some people who were able to direct me to certain sources, especially the National Archive, but the problem is there you need to know what to ask for before you can get it – and then there’s the matter of the Albanian language – which I don’t have.

Then, by sheer chance and extremely fortuitously, I came across the Albanian Lapidar Survey project.

This was where members of the Department of Eagles (a project following artistic development in Albania) obtained funding to go the width and breadth of the country in order to record the locations and document as fully as possible those lapidars still in existence.

As a result of their work three volumes were produced recording the results – all available as downloadable pdfs. Volume One contains a number of introductory articles, some contemporary some historical, surrounding the lapidars. It then lists around 650 lapidars with their location and any other pertinent information, such as any wording on the lapidar, dates of of inauguration and artist/s involved (if known). Volumes Two and Three contain (normally) two images of each of the lapidars surveyed.

For me this was a godsend as in one fell swoop I was provided with a huge database that meant finding these (sometimes) artistic gems was much more than a chance encounter – although it did mean I often had to travel long distances in local transport just to have a few minutes to capture images for my own project and also having to walk long distances along deserted roads to get to, or back from, some of the most remote.

I’m also pleased to be able to say I was also able to make some additions to the list as the information the researchers were working on was never totally complete. Also, for reasons I will go into later, there was a cut-off point in what was considered a lapidar so there are many other artistic works from the Socialist period which I have identified in my travels and which I consider to be ‘lapidars’ but which are not part of the ALS catalogue. These included, especially, mosaics and bas reliefs – sometimes outside and sometimes inside buildings.

Sculptors and architects get involved

Why there was a move (or more exactly a development) from the simple, local, community lapidars to some amazing, truly monumental works of art I will address later. What is clear, however, is from the middle of the 1960s – and for a period of twenty years – the lapidars that appeared in Albania were the creations of trained sculptors and architects.

As was seen in the short video ‘Lapidari’ what might have started out as a simple grave became more elaborate as the wealth and skills in the community increased. Making a monolith higher and facing it with marble was well within the skills of local builders. If there was any decoration it would be in the form of a carved stone which might depict the eagle, the symbol of Albania, with the addition of a star to celebrate the Socialist Revolution. Yes, this needed skill and practice but this was the sort of artistic work which could be produced at a local level by a local artisan.

When it came to producing more than life size human figures, monumental arches or 10 metre high concrete stars, large bas reliefs, mosaics that cover an area of 400 m² or when you cast something in bronze the task and the skills needed rise to a new level.

Lapidars before the mid 1960s

However, as far as I can see there wasn’t a great deal of demand for such skills much before the mid-1960s. From all I have been able to gather (sometimes finding information about Albanian lapidars is like looking for a needle in a haystack) the development of the traditional lapidars depicted in the film ‘Lapidari’ was left very much to the local communities. Apart from a carved memorial stone there appeared to be little decoration – and certainly nothing as ornate as the monuments erected from the late 1960s into the 1980s.

When it came to state involvement in monuments it was very much limited to a few statues of the great Marxist-Leninist leaders, particularly VI Lenin and JV Stalin, as well as some busts of Enver Hoxha.

The first reference I have come across of any of these is a small painting by Abdurrahmin Buza called ‘Voluntary work at the ‘Stalin’ textile factory’ which is dated 1948. This depicts activity in the square in front of the entrance to the factory in the town of Kombinat, just to the south-west of Tirana (along the ‘old’ road to Durrës).

Voluntary work at the Stalin textile factory – 1948

In the middle of the square is a large statue of Joseph Stalin. This is probably the statue which now stands in the ‘Sculpture Park’ at the back of the National Art Gallery in Tirana. I say ‘probably’ as there was an evolution of many of the statues erected in Socialist Albania that started out in plaster or concrete and which were subsequently cast in bronze. This was the work of Odhise Paskali, probably the most famous (and quite prolific) pre-Liberation Albanian sculptor. An exact copy used to stand in the oil producing city of which was called Stalin City, now renamed Kuçove, in the centre of the country, not far from Berat. Unfortunately, I think that one was completely destroyed. It was created in 1949 and originally of concrete – I’m not sure if it was ever replaced by a bronze version.

Joseph Stalin – Kristina Hoshi – Kombinat

Consider the chunky nature of this statue and compare it with the Russian made statue of Joe, that’s also now in the ‘Sculpture Park’, which was presented to the Albanian people in 1951.

Joseph Stalin – Soviet – 1951

For about 17 years this statue stood in pride of place in the centre of Skenderbeu Square in Tirana until it was replaced by the 1968 version of Skenderbeu himself, the work of Paskali, with Janaq Paço and Andrea Mano. It was around this statue of Uncle Joe crowds gathered in March 1953 when news broke of the great leader’s death.

JV Stalin – Skenderberg Square, Tirana

In 1954 Kristina Hoshi (Albania’s very first female sculptor) created the statue of VI Lenin – this now (sadly) vandalised and damaged statue is also behind the National Art Gallery. This was originally made of concrete, later a bronze version was cast, and it stood in the garden that was between the National Art Gallery and the Hotel Dajit, on the road leading from Skenderbeu Square to the Tirana University. (When Uncle Joe was moved from the main square he was placed across the road from Vladimir Ilyich.)

Hotel Dajit with Lenin statue

I’ve also seen a number of old pictures with various busts of Stalin in Tirana

Stalin bust – possibly Tirana 1990

and Durrës.

Bust of Stalin, Durres, main mosque, early 1960s

After his death there were a number of statues erected of Enver Hoxha in various parts of the country but I am only aware of one full statue and that was also created soon after Liberation, in 1948 and in concrete, by Odhise Paskali – though not quite a monopoly in the 20 years after Liberation Paskali never seemed to be short of work. This statue stood outside the Tirana Military Academy.

Enver Hoxha, Tirana (Military Academy)

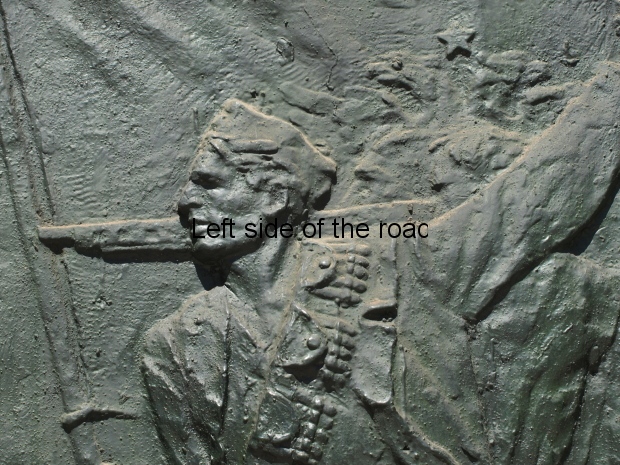

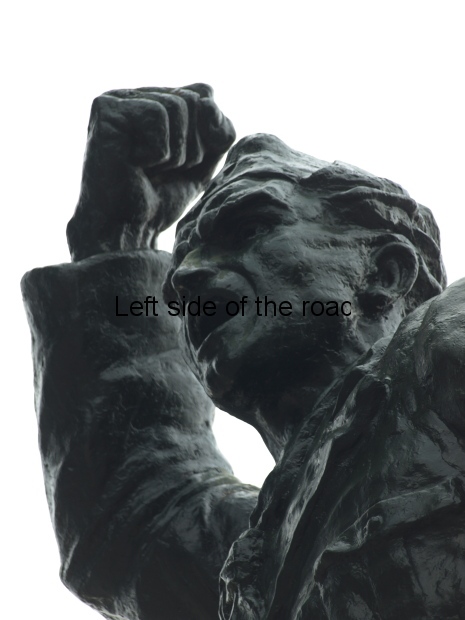

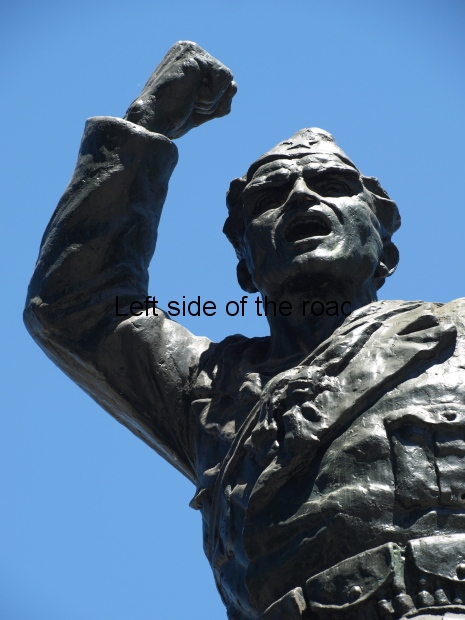

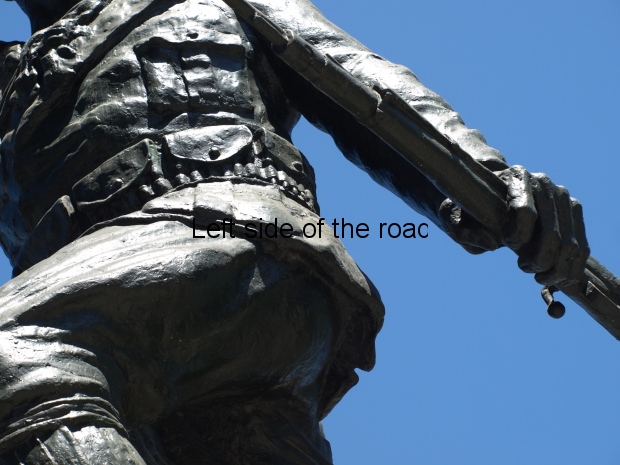

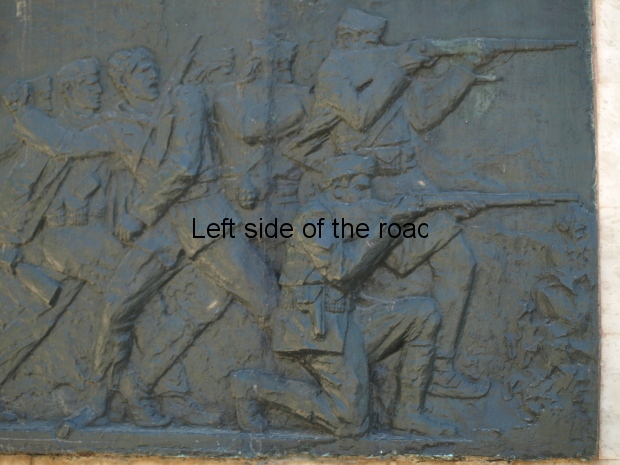

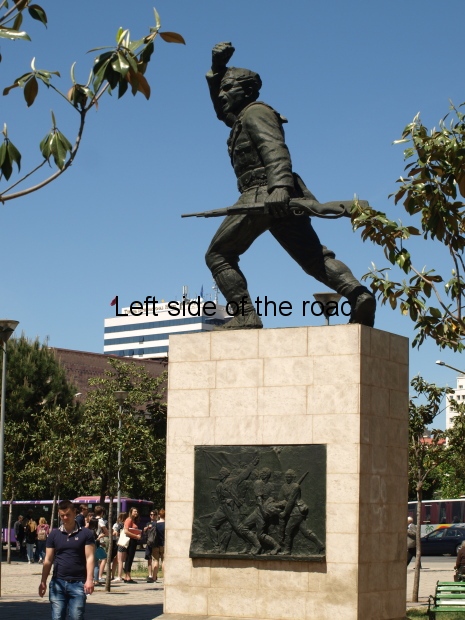

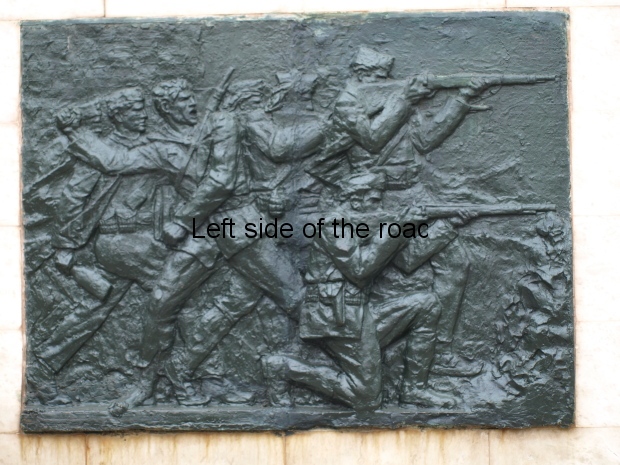

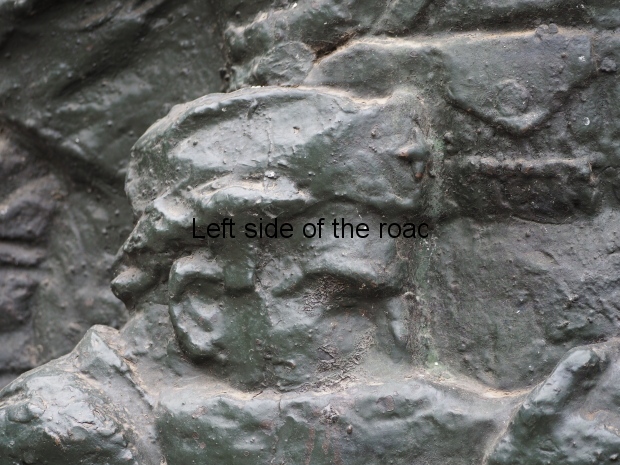

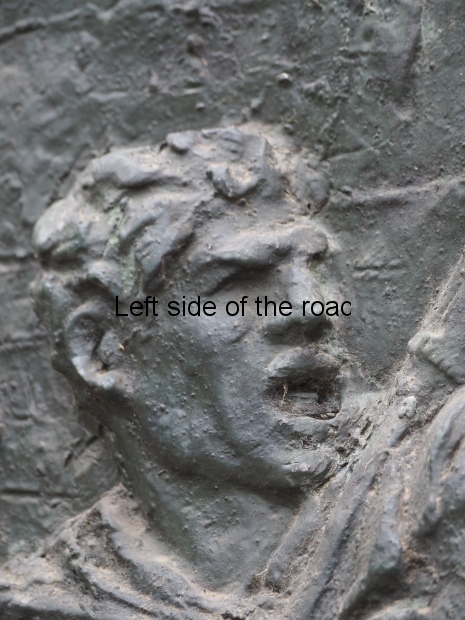

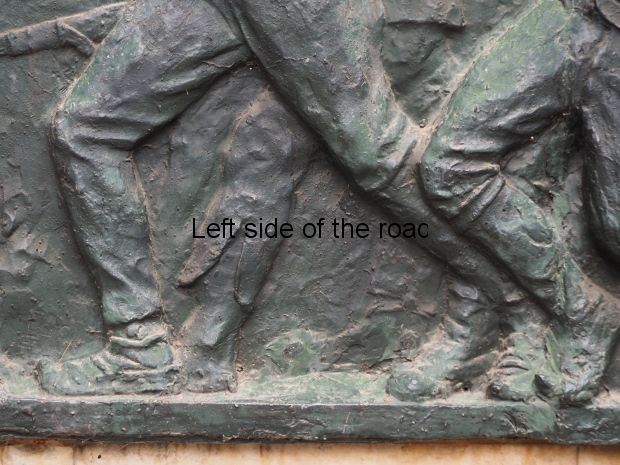

There was another statue which appeared in 1949 and that was the ‘Monument to the Partisan’ by Andrea Mano (another of the ‘old school’ of Albanian sculptors). This still stands in its original location, in the square behind the library and Opera House in the centre of Tirana. This is not one of my most favourite statues. He’s too angry. I’m not against anger but this Partisan seems to be putting all his energy into his anger and not saving it to defeat of the fascist invader.

Partisan, Tirana

Although the work of a pre-Liberation artist it does contain, in the two panels on the sides of the plinth, many of the ideas and images which were later developed and improved upon by those young artists who were the product of the new, Socialist education system. Many of the ‘old school’ artists (Kristina Hoshi, Odhise Paskali, Janaq Paço, Abdurrahmin Buza, amongst others) became teachers in first the Tirana Artistic Academy and later (from 1960) the Higher Institute of Art – part of Tirana University.

Before moving on it might be pertinent to mention here that in the immediate years after Liberation Albanian artists didn’t have access to foundries to cast any metal statues and therefore depended upon their work finally being realised, and Budapest seemed to be the place of choice. By the 1950s things had changed but artists didn’t use commercial foundries but ones specifically for artists which made the structure in pieces, which were then welded together.

And this was the state of Albanian public lapidars until the middle of the 1960s. So what happened to make a significant change in emphasis in Albanian Socialist Realist Art?

The emergence of the unique Albanian lapidars

The short version of the chronology of events. March 5th 1953 Joseph Stalin dies. February 25th 1956, on the very last day of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khruschev gives a ‘secret’ speech denouncing Comrade Stalin – modern revisionism was now entrenched in the first Communist Party to achieve success in a Socialist Revolution. This caused confusion in many Communist Parties world-wide but there was more clarity in the Party of Labour of Albania and also in the Communist Party of China (as well as groups within various parties in some other countries).

From February 1956 until the end of 1960 meetings were held, letters went back and forth and the debate got more acrimonious. This all came to a head at an extended Meeting of 81 Communist and Workers’ Parties in Moscow in November and December 1960. At this meeting Enver Hoxha gave one of the most courageous speeches in defence of Marxism-Leninism (Speech delivered at the Meeting of 81 Communist and Workers Parties, in Moscow, on November 16th 1960), with a stinging criticism of the revisionists in their own home.

Enver at 81 Communist Parties Meeting 1961

But for such a stance there were consequences – and a price to pay. Within days any support from the Soviet Union withered away and links with China had yet to be strengthened. For a while Albania was virtually alone – surrounded by hostile forces – whether capitalist or revisionist. A new approach was needed.

Albania’s Cultural Revolution

The new approach was what can best be described as a Cultural Revolution. People know more about the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China but it had an equally important impact upon Albanian society. It’s also no coincidence both countries arrived at the same conclusion at the same time.

The events of the previous five or six years had shown the problems facing the world’s proletariat and the International Communist Movement. If the Soviet Union, the first ever Socialist state, with its achievements in collectivisation and industrialisation, with the huge sacrifice the nation had made in the destruction of the Nazi beast, could succumb to revisionist betrayal then matters were not as secure as all had thought in the heady days of the late 1940s when the number of people attempting to construct Socialism had increased exponentially.

Any comparison with Albania and China in respect of their Cultural Revolutions would serve no purpose here and would be a vast topic. But if I were to choose a particular event when the decision on the way forward for Albania was laid out for the future it was at the 15th Plenum of the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania which was held in October 1965. Ramiz Alia gave the main report (which I haven’t been able to track down) but Enver Hoxha made a contribution towards the end of the meeting where he made (to date) his clearest and most succinct analysis of the role of culture in the next stage in the development of the Revolution.

Enver Hoxha on the Cultural Revolution

The cultural activity with the masses should aim at propagating the ideas of our Party, at creating the materialist world outlook. In this field, attention should be given to the struggle against meaningless prejudices and faiths, by spreading scientific knowledge among the working masses.

[Enver Hoxha, Selected Works, Volume 2, p550. Report to the 3rd Congress, May 25th 1956]

The speech in October 1965 was later published as ‘Literature and the arts should serve to temper people with class consciousness for the construction of Socialism’, but the page numbering to the quotes below refer to Enver Hoxha, Selected Works, Volume 3.

I won’t comment on what Comrade Enver says in this speech, just list those sections which I think are most relevant in the context of the development of the lapidars.

From this stems the great role which literature and the arts should play in the inculcation and development of this consciousness, closely linked with the period we are going through, with the efforts, the struggles for the construction of socialism, with the struggle on a world scale against imperialism, the bourgeois ideology and its variant, modern revisionism, etc.

The consciousness of man and that of society is not something petrified, unchanging, formed and developed once and for all. It undergoes positive and negative changes, it alters in accord with the material-economic forces, with the class struggle, the revolutionary situations, the relations between the antagonistic and non-antagonistic classes, with the ideas which inspire the class struggle, the revolution, and so on. p833/4

In such conditions the tasks of the Party, and those of literature and the arts in particular, in tempering the people with working class consciousness, with the morality of the working class, in order to go ahead successfully with the construction of socialism, are glorious, but by no means simple. p835

I want to turn to the concrete reality and to emphasize with what a sacred duty and a heavy burden of responsibility our Party and people have charged you writers, poets, artists, composers, painters, sculptors, etc. Like everyone else, you, too, must carry out these tasks conscientiously, with your struggle and toil. Your valuable and delicate work must be inspired by the Marxist-Leninist ideology, because only in this way and by basing yourselves on the people, on their struggle and efforts, will your militant and revolutionary spirit display itself and burst out in your creative works and activity, and thus you will become educators of the masses who accomplish great works. p836

There are some who think, and think mistakenly, that by making a flying visit to the base, by sitting in a cafe, cigarette in hand, in order to see the various types whom they want to put in their work passing in the street, or who think that by walking through some factory or plant, they have gathered the necessary material and go home, where they start to write superficially, and sometimes entirely back-to-front, about those things and people that they ‘photographed’ in passing. Thus the world of such a person is restricted by the narrow petty-bourgeois concept of the role of the writer, and he thinks that his head is capable of doing great things. But can it be said that the engineers of the hydro-power stations or those who drain the marshes do not work with their heads, and that the writers alone have this privilege? No! But the engineer, quite correctly, works with the people, studies the environment, the nature, draws plans, checks them again with the people, with the best experience of others, encounters difficulties, struggles with them till he overcomes them. But should not our writer and artist work in this way, too? Then why do we have to point this out to him so many times? p838

You cannot become a real writer simply because you have talent, if you do not develop this talent, this means, by learning, if you do not work on it, test it, and hammer it into shape on the great anvil of the people and if you do not study a great deal, and first of all, the social and economic sciences. Only in this way will the writers provide the working class and the peasantry with worthwhile works. p839

I do not want to repeat anything of what was said in the report delivered by Comrade Ramiz in regard to the range of themes and our objective of tempering the new man of the new socialist Albania, of inspiring him with the heroism of the National Liberation War, with the heroism and the sacrifices of the people and the Party, with the ideas of the partisans, with their aspirations and dreams, in order to inspire and educate him with the rich, exalting, living reality of the construction of socialism in our country, this period which is one of the most brilliant in the history of our people. p840

The aim of the Party is to create new values. p842

In order to combat the negative consequences of the past, we have to explain to the younger generation the origin, the reasons that caused the development of these things. Our fathers and our generation have experienced those situations, but the others have not. p843

A great inspiration is urging onward a new generation of wonderful writers and artists, who are winning renown and becoming dear to the people. Our Party, through its work and maternal care, must protect, educate and encourage these young people with all its means. p843

The Party’s policy in the field of art and literature has been and is clear to everybody. It will always give powerful support to the good works, the correctly inspired works, those that educate, mobilize and open perspectives. p846

In regard to literature and the arts which are developing in our country, as in regard to the other issues, there are not two moralities, but only one, the proletarian morality of the working class. The ideas expressed in the works should conform to this morality. p847

The Cultural Revolution and lapidars

However, there were a couple of more elaborate lapidars which proceeded this 1965 meeting. Both were inaugurated in 1964, both were in Përmet and both were by the same sculptor, Odhise Paskali. They also gave an indication of what was to come – both in a positive and in a (possibly) negative sense.

The first one to discuss is called ‘Shokët – Comrades’ and is located in the town’s Martyrs’ Cemetery – a short distance from the town centre along the road to Tepelenë. The image is instantly recognisable by anyone who has ever entered a Catholic church. The ‘inspiration’ for the image was that of the ‘Pietà’ which first appeared in Germany in the 14th century but really took off during the Italian Renaissance.

This is the image of Christ after he had been taken off the cross and is in the hands of his mother – and often the Magdalen or others. In Përmet a wounded/dying Partisan is tended by two of his comrades, one male one female. His situation is desperate and he is unlikely to survive but his comrades attempt everything they can. This is an image of comradeship but, I would argue, too close to the imagery of Christianity. You could even argue there’s a suggestion of ‘resurrection’ in the final Liberation that occurred within a year or two of the death of the Partisan.

Shoket – Comrades

I don’t think it is surprising Paskali came up with this image. He stayed in the country after Liberation and produced works of art for the Revolution as well as passing on his knowledge to a younger generation. But he was born in a different world where religion held sway. I think it’s certain no such image, even one produced by such an esteemed sculptor as Paskali, would have been produced after 1968 – when Albania pronounced itself the first atheist state in the world. I also think this sort of image falls into the category Enver was thinking about in 1956 when he wrote about ‘the struggle against meaningless prejudices and faiths’. Putting a Partisan uniform on the subjects and a Red Star on their caps doesn’t make the image any less Christ-like. But as an indication of the way forward the placing of such a monument in a Martyrs’ Cemetery was something repeated throughout the country and there is no town of any size which doesn’t have a sculpture of some kind.

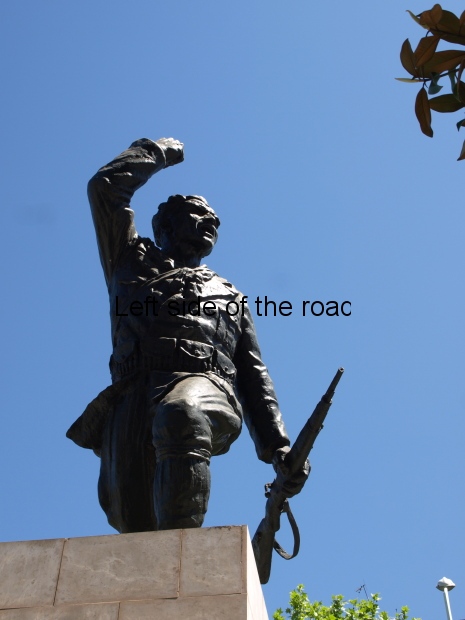

The second work by Paskali is a bronze statue of a Partisan, fully armed and looking very determined, which is part of the lapidar commemorating the Përmet Congress of May 24th 1944 – where the Albanian Communists decided on the Provisional Government structure six months before their eventual victory over the Nazi invaders in November of that year. It was inaugurated on the 20th anniversary of the Congress.

Permet Congress

The trend which this sculpture started was the commemoration of the sacrifice and achievements of the Albanian Partisans and their defeat of the Italian and German fascists. Now I’m not against this trend necessarily. As a tool in the education of future generations they should be made aware of what their (now) great grandparents fought for to finally achieve true liberation of the country and lapidars had a role to play in the process.

But Socialist Realist Art has two functions; remembering the past and indicating the road for the future. It’s a matter of proportionality.

Alongside this celebration of the more or less recent past in the 1960s was also the celebration of the life and Skanderbeu, the 15th/16th century nationalist leader. There are many monuments to him and his acheivements throughout Albania, virtually all erected during the Socialist period including the large equestrian statue which stands in the centre of the main square in Tirana bearing his name. When this statue was first erected in 1968, the 500th anniversary of Skenderbeu’s death (the work of Odhise Paskali, Janaq Paço and Andrea Mano) the Russian made statue of Joseph Stalin had to make way and he was moved down the road to accompany VI Lenin. Most, though not all, of these statues to the mediaeval leader are some of those which get the most attention in the present day capitalist Albania – with one, in Krujë, being totally reconstructed in 2012 (but it’s far from one of the best lapidars.)

Obelisk of the Battle of Zidoll (April 24, 1467)

Whatever was to become the trend through the 1970s into the 1980s 1966 did see the inauguration of a lapidar representing the new, Socialist future. This was the Monument to Agrarian Reform (that is the commemoration of the first Cooperative farm established, in 1946, in the area of Krutje, just south of the town of Lushnjë). The lapidar is the work of the sculptor Kristaq Rama (whose son, Edi, is presently Prime Minister of the country) and was unveiled to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the event. Representing a Socialist and collective future it has not been treated with a great deal of respect in the last twenty years.

Monument to Agrarian Reform – Krutje

The movement of monumental lapidar construction takes off

There are close on 200 lapidars, still in existence, in Albania which have some artistic and/or architectural significance (whilst in no way denigrating the simple monoliths commemorating the fallen Partisans), some in better condition than others. I’m in the process of producing a ‘close reading’ of the many I have had the chance to see but it’s a long process and the project has yet to be finished.

Some tell a simple tale, some a more complex one. Here I’ll chose one of each as a means of an introduction to the uniqueness of the Albanian lapidars.

For me the most truly monumental of the monuments is the Arch at Drashovicë, which is located in the beautiful valley of the Sushicë River, which runs parallel to the coast on the other side of the mountain range above the port town of Vlorë. It is the work of one of Albania’s finest post-Liberation sculptors Muntaz Dhrami (with the assistance of architects Klement Kolaneci and Petrit Hazbiu) and was constructed in 1980. It tells the story of two victorious (for the Albanians) battles against the Italian invaders, first in 1920 and then in 1943.

Drashovice Arch

This is history written in stone and it’s a joy to look at all its elements and try to interpret that story – a story too long to tell here. However, although the lapidar is really in the middle of nowhere, Drashovicë is only a small country village, there is obviously a great deal of respect for the story it tells and the way it has been told as on my various visits I have never noticed any serious damage or blatant vandalism – something which can’t be said for many monuments whether in towns or in the countryside.

The simple story is represented by a statue of a Partisan and a young girl in the village of Borovë, in the south-east of the country, not far from the mountainous border with Greece. In July 1943 a Nazi convoy was attacked not far from the village and, as was their wont, the fascist retaliated three days later, on the 19th, and ended up killing a total of 107 people (some being burnt alive locked in the local church) and all the buildings were destroyed.

Partisan and child – Borove

In 1968 a lapidar was erected to commemorate this massacre but it underwent radical changes a number of years later and the statue of the Partisan and child was separated from the main memorial and placed on a plinth beside the main road running south. Although the separation does take away somewhat from the story (the main monument to the atrocity now being on top of a hill and can easily be missed if you didn’t know what you were looking for) I still think it is one of the most charming of the Albanian lapidars.

Before I move on from the story of the sculptural lapidars it might be of interest to know that until some of the later monuments (basically those constructed after the death of Enver Hoxha) it wasn’t the norm for sculptors to ‘sign’ their work. Although that, today, makes identification of the artist sometimes difficult I’ve always thought it was a good trait in the history of Albanian Socialist Realist Art.

Enver Hoxha and the Vlorë Independence Monument

I’ve already said there was a great emphasis on the historical, pre-Socialist Liberation struggles in the construction of the lapidars from the mid-1960s. One of the largest of these – both in size and in importance to the Albanian nationalist movement – is the Vlorë Independence Monument which commemorates ‘Independence’ in 1912 from the Ottoman Empire. The reason I mention it here is because Enver Hoxha took a personal interest in the design of this monument, visiting the sculptors in their studio to have a look at the proposed maquette and then sending the artists a letter with his ideas.

I have no problem with this as I don’t see why artists who depend for their livelihood upon the rest of the working population shouldn’t be directed and monitored in the work they produce. Although I’ve come across little concrete evidence such discussions took place before some of the lapidars were installed it would have seemed bizarre, to say the least, if a monument was to sometimes dominate a locality was not first discussed with and became a matter of consultation with the local people.

When it comes to the involvement of the leader of the country, from the time of Liberation in November 1944 till his death in April 1985, I think it was Enver Hoxha’s personal enthusiasm for such monuments which pushed their construction after 1965. The latest lapidar I’m aware of is the large statue ‘Toka Jone – Our Land’ in the middle of the main square of Lushnjë, which is dated 1987. Lapidar construction seemed to stall after Enver’s demise.

Mosaics and bas reliefs

As I’ve said before it’s not just in the public monuments and statues the story of Albania, its nationalist past, its victory over the fascist invaders and its hopes for the future, are on display – although as with the lapidars there physical state varies depending where in the country they are found and with what respect they are held by the local community.

The mosaic seen by virtually all visitors to the country is the ‘The Albanians’ on the facade of the National Historical Museum in Skenderbeu Square in Tirana. Images depicting a couple of thousand years of Albanian history covers a space of around 400m². Unfortunately this is starting to feel the effects of neglect and every time I see it the damage looks worse. My real fear here is that one day a catastrophic accident will occur with pieces falling off and it will be removed ‘for safety reasons’.

One point to stress about the images in this mosaic, and which is repeated in virtually all the lapidars I’ve seen, is that when women are represented they are almost invariably armed, when often the men aren’t. Here the policy of the Party of Labour of Albania attempting to overcome the traditional, secondary role of women in Albanian is reinforced by showing them the way to achieve equality.

National Museum Mosaic – original

Of the other mosaics of interest one is on the side of the town hall building in Ura Vajgurore, not far from Berat,

Bashkia Mosaic – Ura Vajguror

and those on either side of, what used to be, the main entrance to the Vlorë Palace of Sport.

The Pickaxe and Rifle – Vlora Palace of Sport

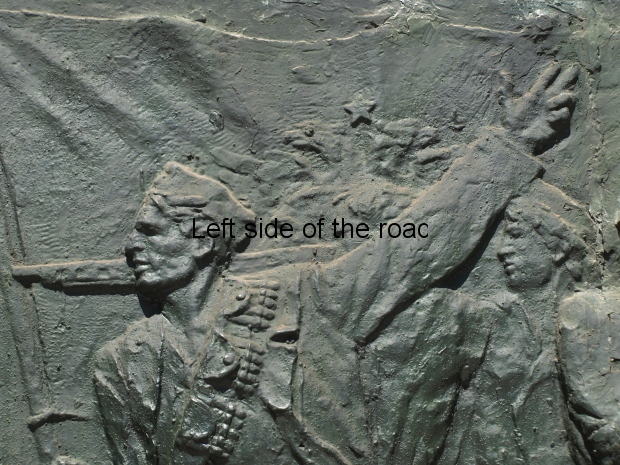

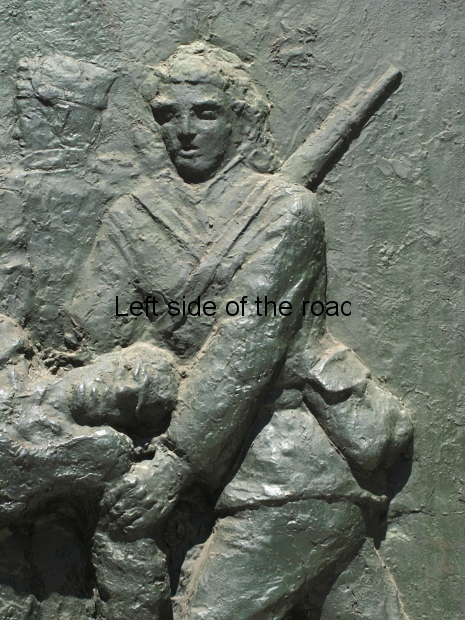

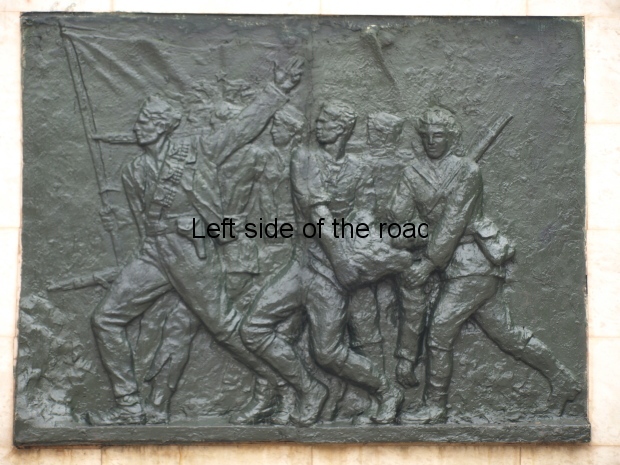

When it comes to bas reliefs a few examples are:

the one commemorating a demonstration by high school students and their teachers against the occupying Italian fascist forces in Gjirokaster,

Gjimnazi School Revolt – Gjirokaster

one with a completely different approach, the bas relief on the front of the Radio Kukes building in the north-eastern town of Kukes, not far from the border with Kosovo,

Bas relief on Radio Kukesi

and the magnificent panel beside the entrance to the historical museum in Ersekë.

Erseke Museum Bas Relief

Then came 1990

Immediately after the success of the counter-revolution it was the statues of Enver Hoxha, most of them only having been erected after his death in 1985, in various parts of the country, which were the target for those who hated Socialism.

The first one to go was the large statue erected in Skanderbeu Square, on a platform created between the National Historical Museum and the Bank of Albania. This went down on 20th February 1991.

Enver Hoxha in Skanderberg Square – Inaugaration

Others were to follow in different parts of the country (although the actual chronology is uncertain). Perhaps the biggest of all was the marble statue placed in Gjirokaster Old Town, Enver’s birth place. This huge statue was destroyed by local reactionary forces from the Greek community in August 1991. The platform created to hold the statue is all that now remains – the site being turned into a bar area in the summer.

Enver in Gjirokaster

I don’t agree with the destruction of these statues or the ransacking of the Enver Hoxha Museum (often called the Pyramid) in Tirana. However, I don’t consider these statues fitted into the concept of Socialist Realist Art. There were many busts of Enver in public buildings and there was a small industry (based in Kavajë) producing ceramic busts for peoples’ homes. But I think it was a political mistake to have created these very big (many times life size) statues after his death.

Or perhaps it wasn’t a mistake. The enforced isolation of the country had been putting strains on the system for a while and as happened in the Soviet Union after the death of Stalin and in the People’s Republic of China after the death of Mao it was obvious reactionary forces would come out of the sewers to sow dissension and reap the harvest of discontent. The anger directed at the statues of Enver at least meant they didn’t break the head of Ramiz Alia – who seemed to bow down to any pressure to save himself when the reactionaries were able to convince the enough disaffected of the working class to take to the streets. (He has gone down in my estimation during the process of writing this.)

But once the reactionary wave gained force the lapidars which celebrated the achievements of the Socialist past were soon to be fair game. Statues of Uncle Joe were taken down on the orders of the gutless and traitorous Ramiz Alia on the night of the, then considered, anniversary of Stalin’s birth, 21st December 1990. Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was spared that night but was taken down on the June 21st 1991.

And those few that had images of Enver Hoxha also became targets of concerted political vandalism. Such was the fate of Monument to the Berat Meeting (held in October 1944 to decide on the structure of the Government after the imminent defeat of the Nazi invaders). This large lapidar was in the centre of town and was inaugurated in 1969.

Monument to the Berat Meeting, 1969

Another tragic loss was the statue of the Four Heroines of Mirdita. This was a monument to four women from the area around the town of Rreshen, in the northern part of the country, who had played a part in the defeat of the fascist invaders before Liberation in November 1944. They were assassinated by reactionary (often foreign supported) forces operating in the north of the country for their continued efforts in both the construction of Socialism (in 1948 and 1949) and in attempting to build a society where women played a full and equal part with men, thereby challenging the old ideas and thinking.

The Four Heroines of Mirdita – and the sculptors

As an example of the hatred in which pieces of bronze are held by the reactionaries in charge of present day Albania is the story of the statue of the Five Heroes of Vig. The original statue stood in the centre of a roundabout in the centre of Shkodra. It was later moved to be beside the town’s Martyrs’ Cemetery – which originally would have been a glorious site, right beside the River Kir but, for a time, it became the town’s rubbish dump. Here the statue was subject to mindless theft vandalism as the pieces of bronze easily removable were stolen for scrap. After a long, and sometimes heated debate, the statue was moved yet again, this time to a roundabout on the northern edge of town on the main road north. Not the place of honour it once occupied but at least a dignified location – for the time being.

5 Heroes of Vig – plaster, 70’s

And that’s not to mention Red Stars. Obliterated, damaged or painted over. If there was a target second only to Enver Hoxha it was the stars.

What has ‘democracy’ offered in its place?

The simple answer; not much.

When the sitting right-wing government in 2012 realised it was on its way out they went on a spending spree when it came to the commissioning of public monuments. I have no intention in discussing what was produced here, merely to give an idea of what the capitalist Albania considers is the art for the people.

Words aren’t really necessary.

This was placed in the middle of the roundabout close to the bus station for buses and furgons to the south in Tirana;

Fascist Eagle – Tirana

And one to make you wonder where the present day Albanians have placed their dignity and pride is a statue of the coward Zog – he ran away when the Italians invaded on April 7th 1939. This one is in Burrel, in the centre of the country, there’s at least one more in Tirana.

Zog in Burrel

By way of a conclusion

I believe the Albanian lapidars (and the other public works of art) produced between 1964 and 1990 were a unique and distinctive addition to the catalogue of Socialist Realist Art. It served its purpose but other factors meant it didn’t achieve, or maintain, what it set out to do – the creation of a socialist mentality.

Whether matters will change in Albanian such that they recover the respect they had in the past is unlikely in the short term but they do provide, at least, an example of what is possible when art and culture is created for the working class.

March 2020