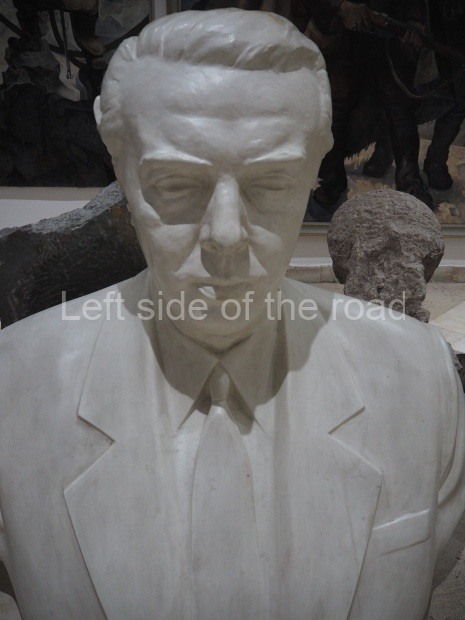

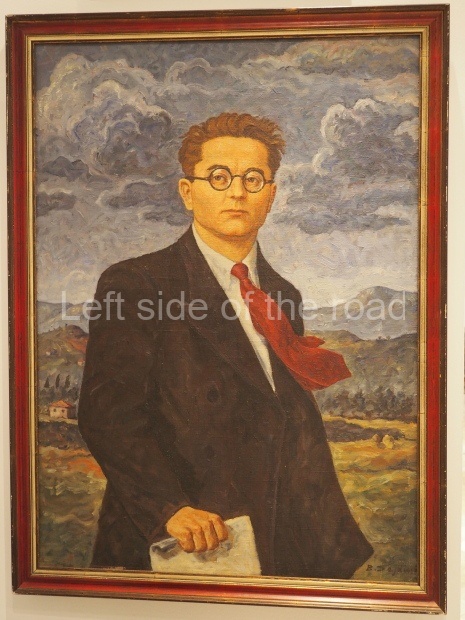

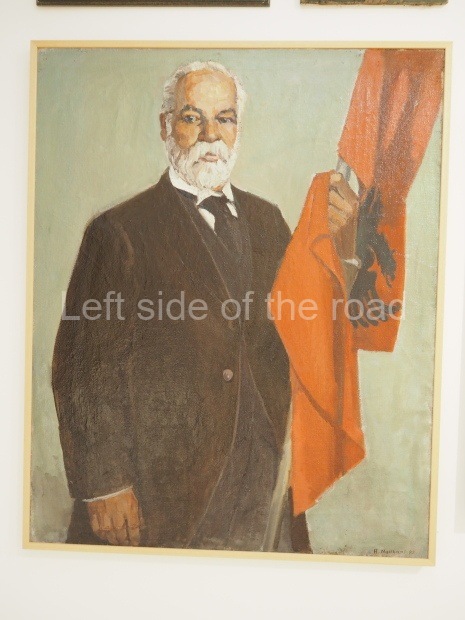

Enver Hoxha

More on Albania …..

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told

Enver Hoxha – The need for a Cultural Revolution in Albania

Introduction

The section below entitled ‘The further deepening of the ideological and cultural revolution’ comes from the Report of the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania presented by Enver Hoxha at the Fifth Congress of the Party, held at the beginning of November 1966.

It’s presented here to remind people that the concept of an ‘ideological and cultural revolution’ had existed since (and even before) the October Revolution in Russia in 1917. The works of both VI Lenin and JV Stalin make reference to the need to change the way people think and act as an integral component in the construction of Socialism. The development of the economy to suit the needs of the vast majority of the population, the taking of the means of production by the people from private owners with the collectivisation (and nationalisation when collectives were further developed to the situation of State owned farms) of agriculture and the building of a modern industry would not automatically lead to Socialism. What needed to change were people’s ideas.

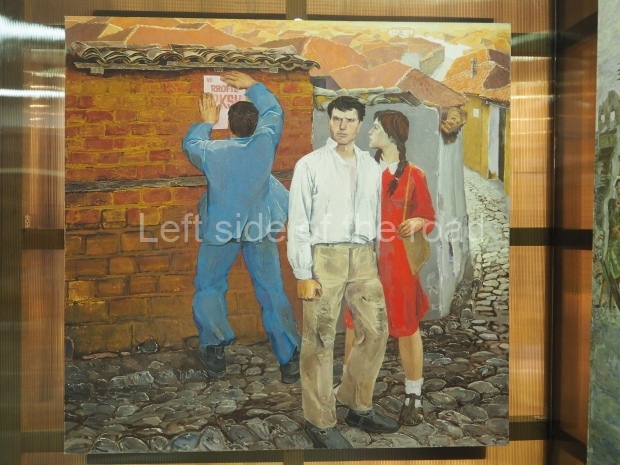

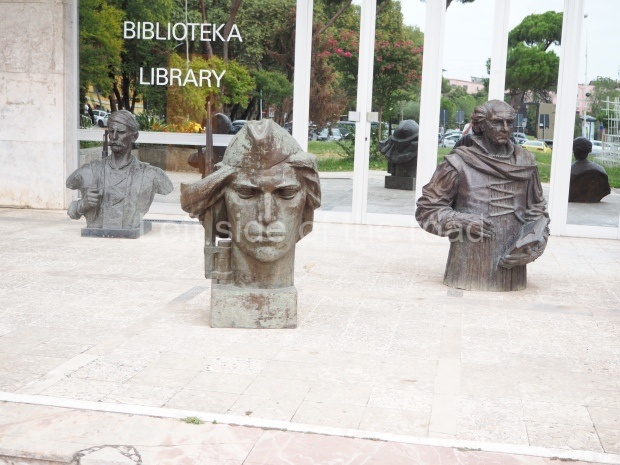

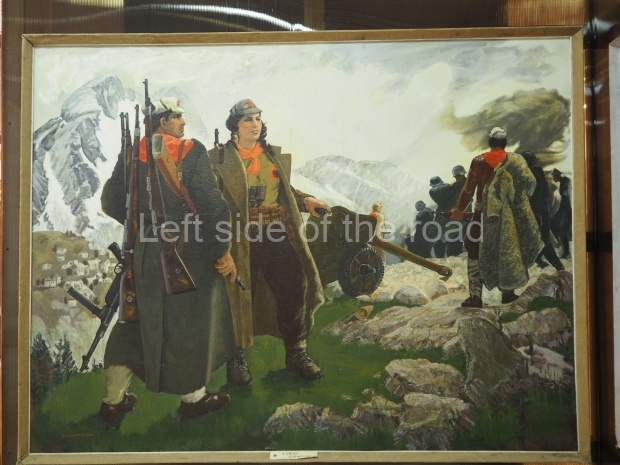

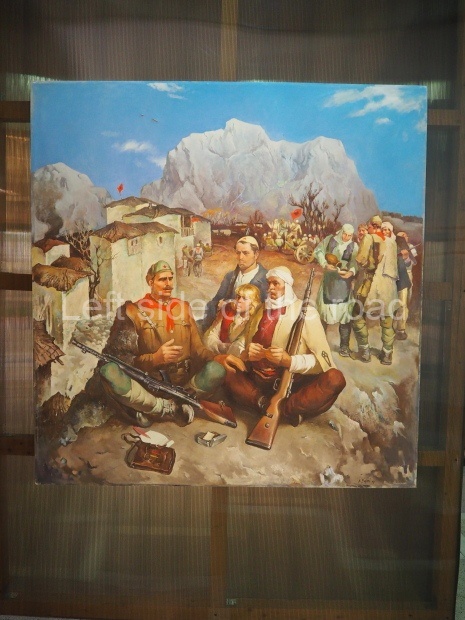

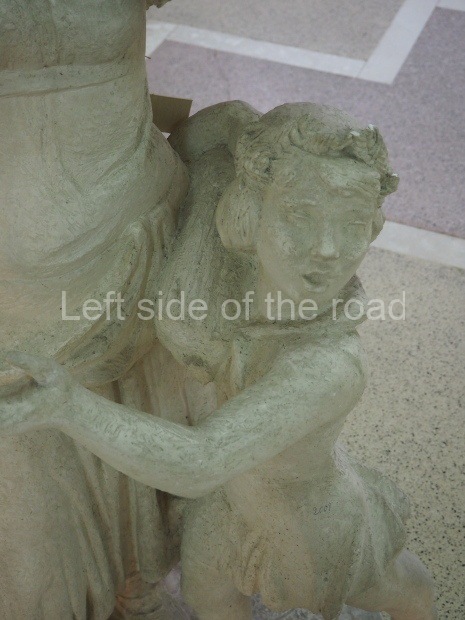

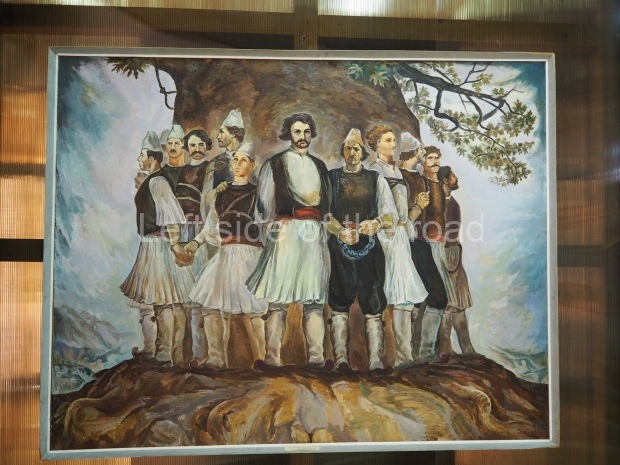

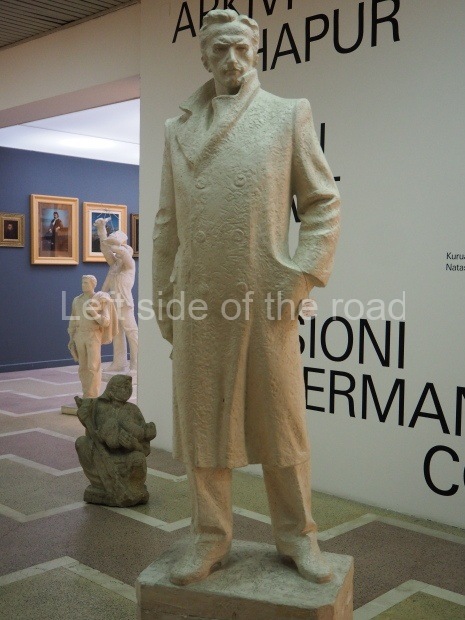

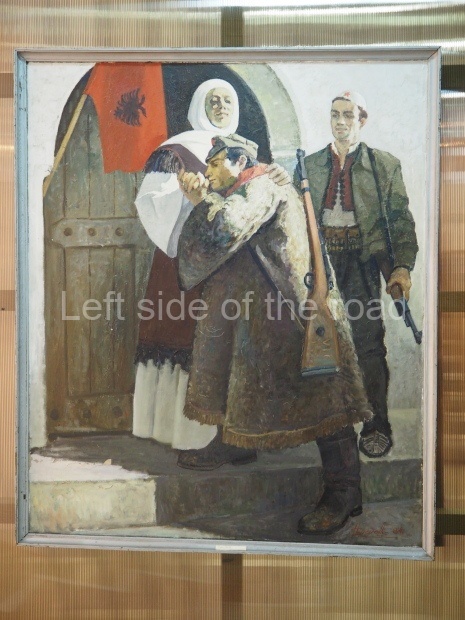

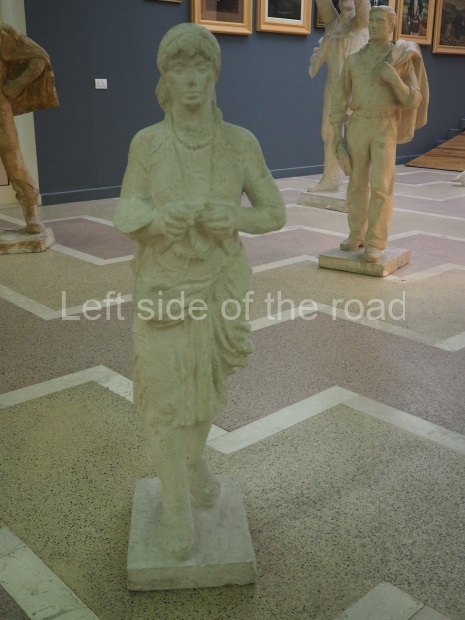

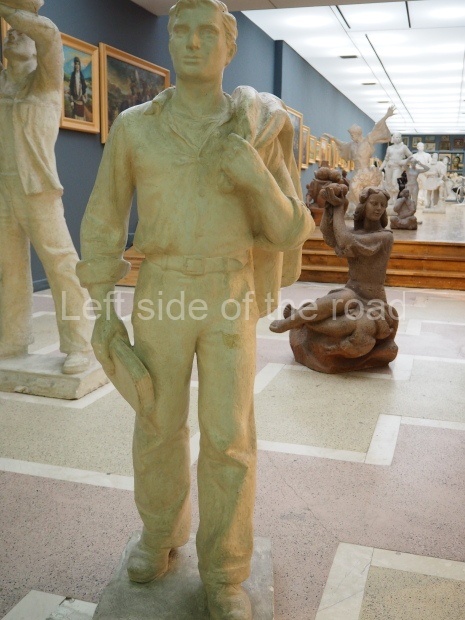

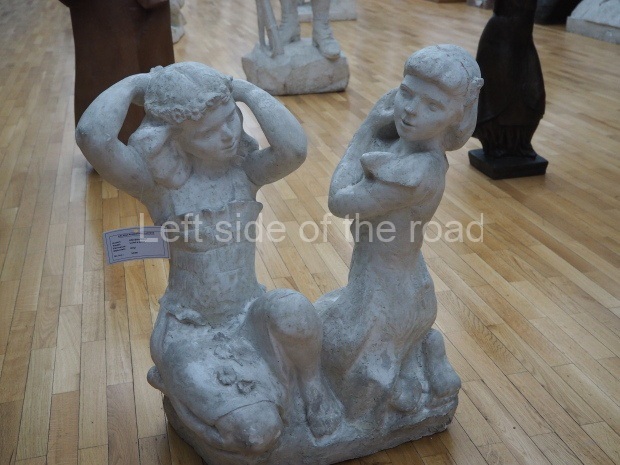

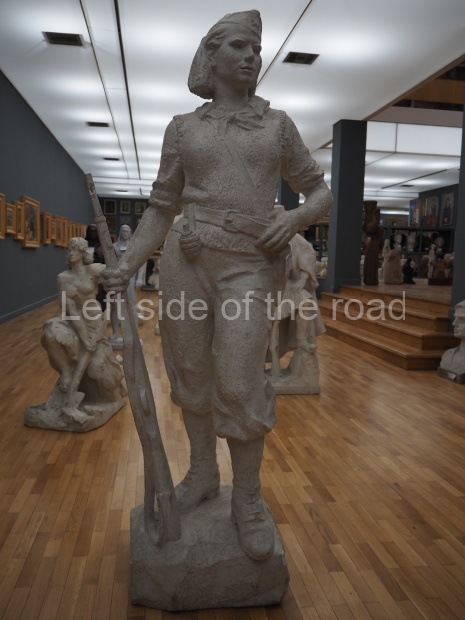

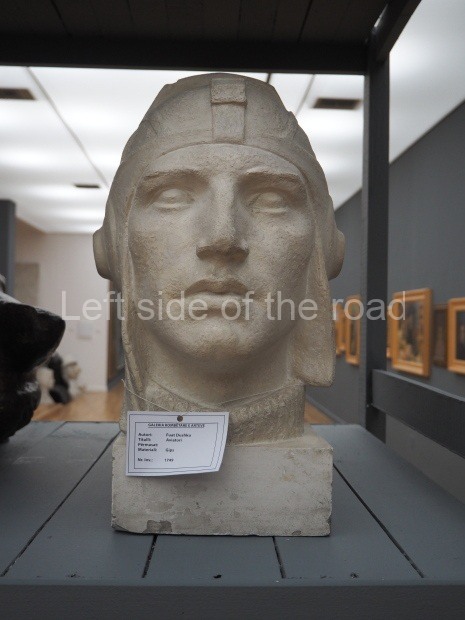

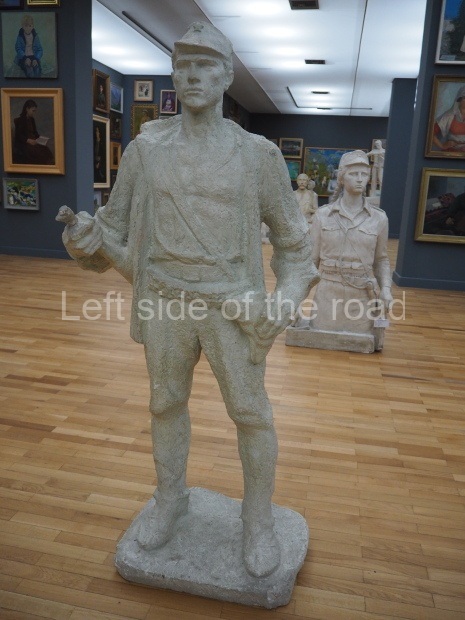

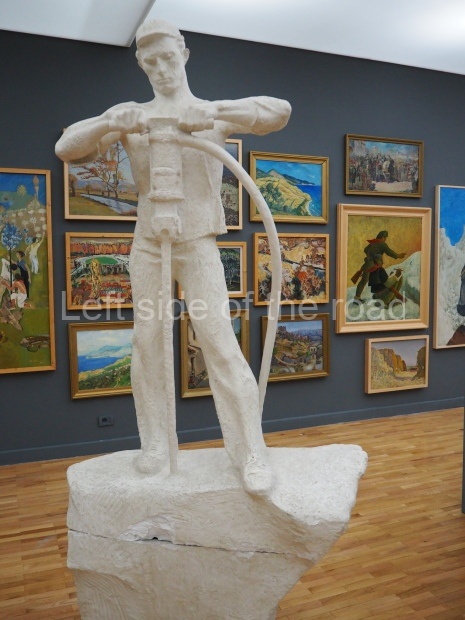

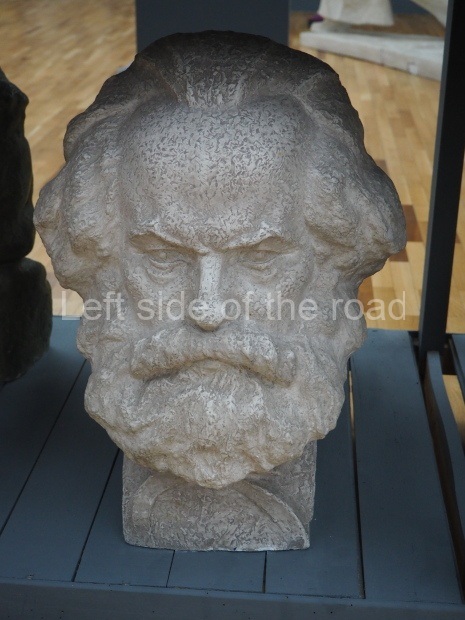

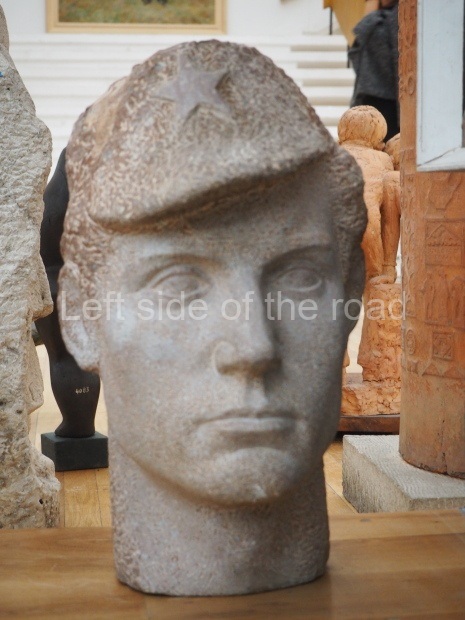

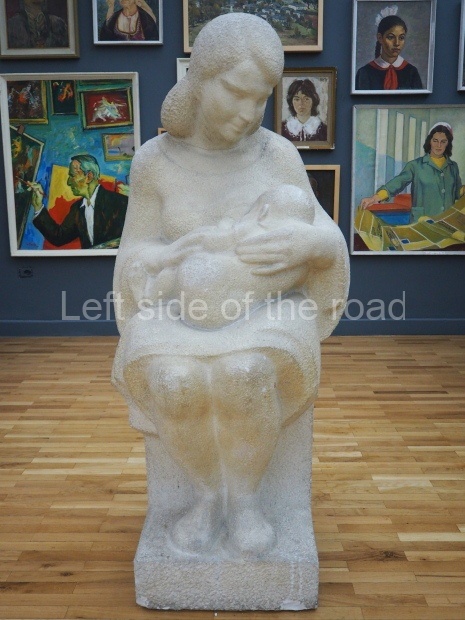

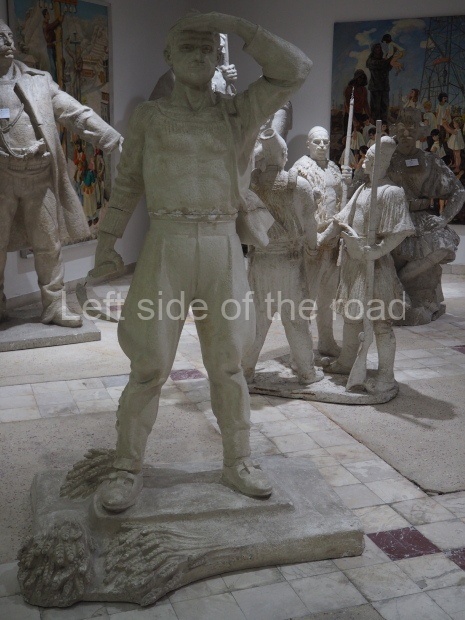

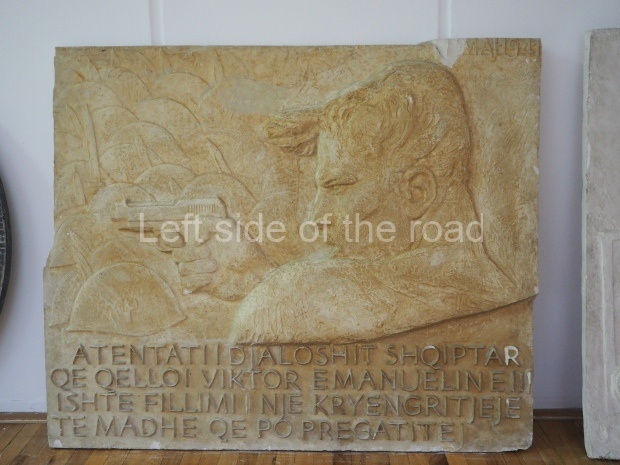

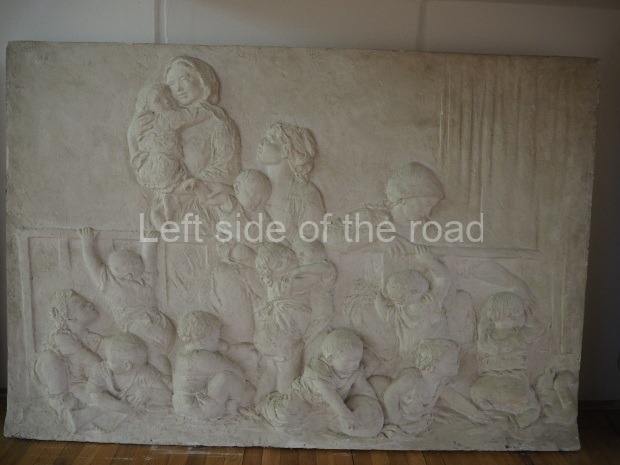

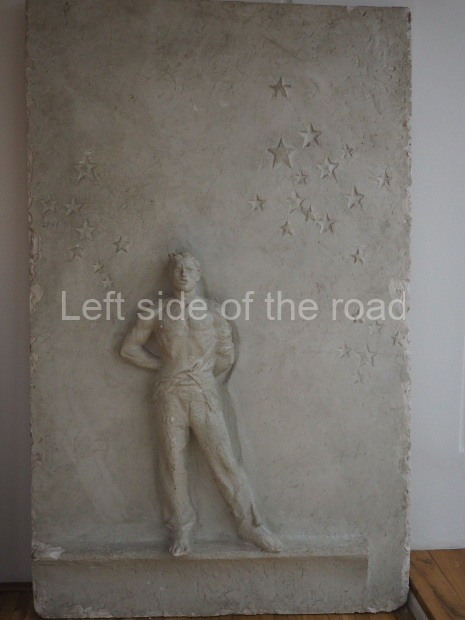

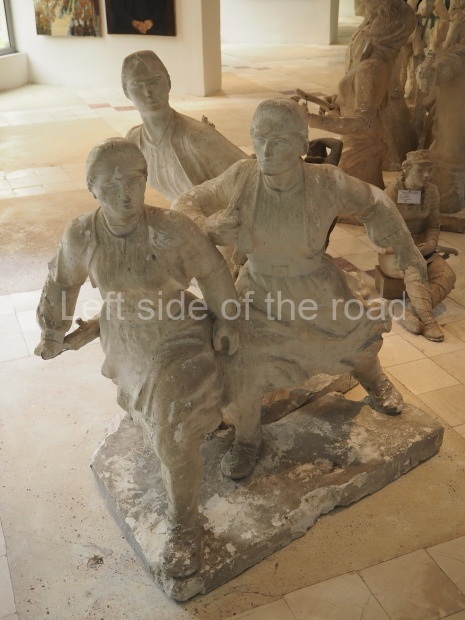

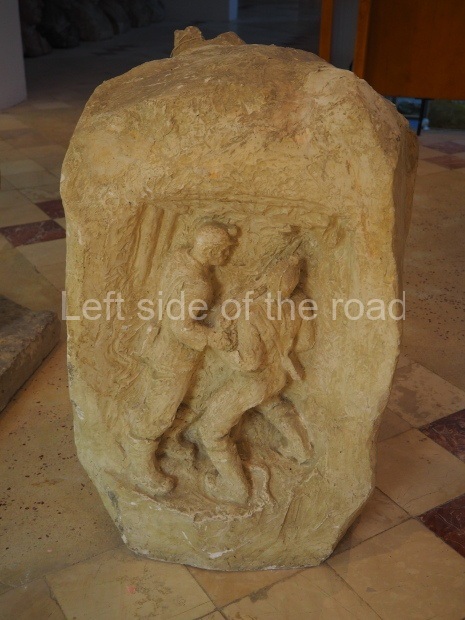

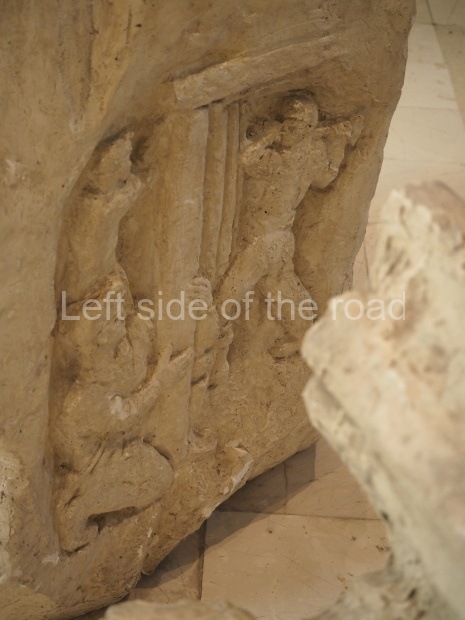

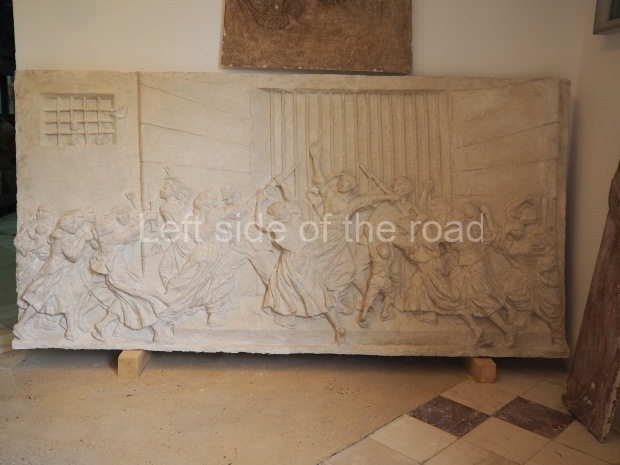

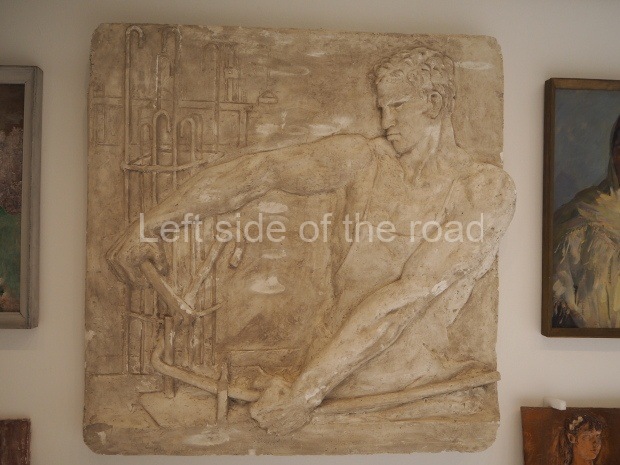

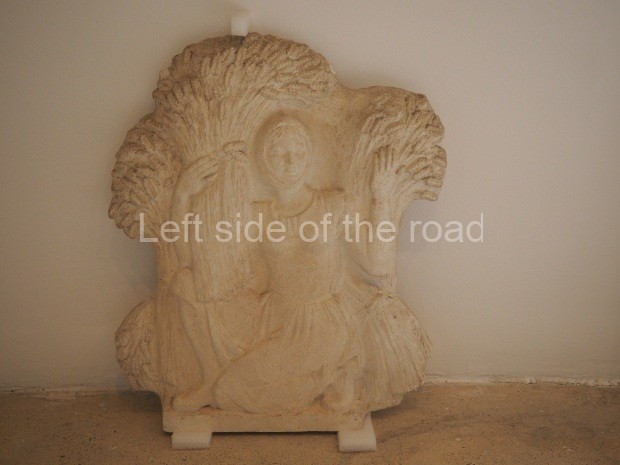

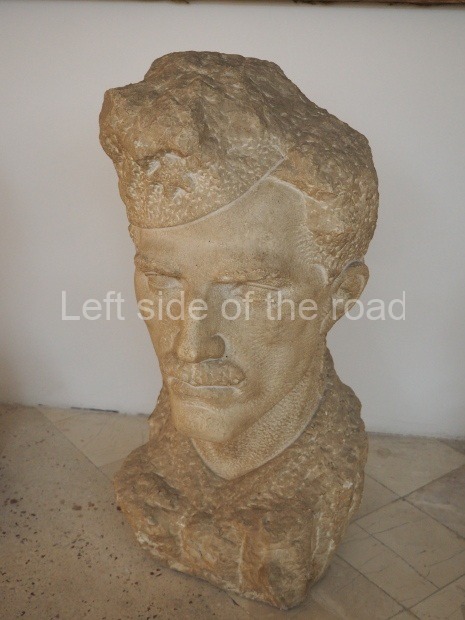

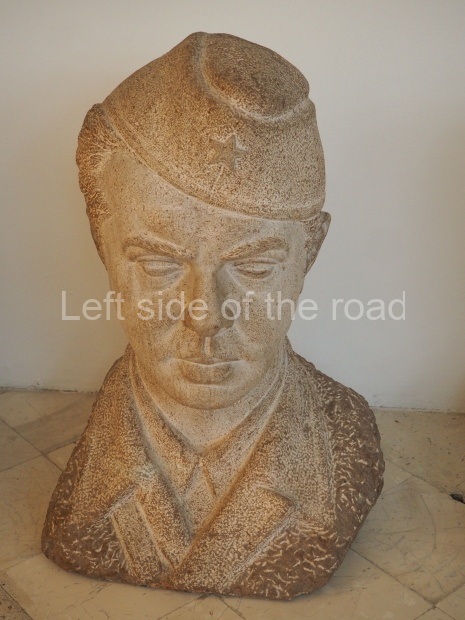

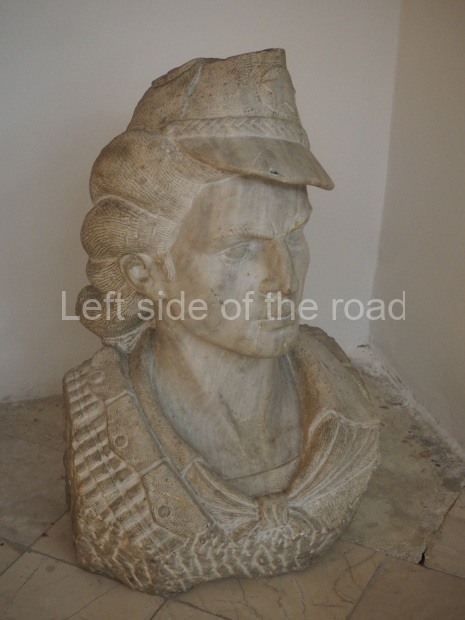

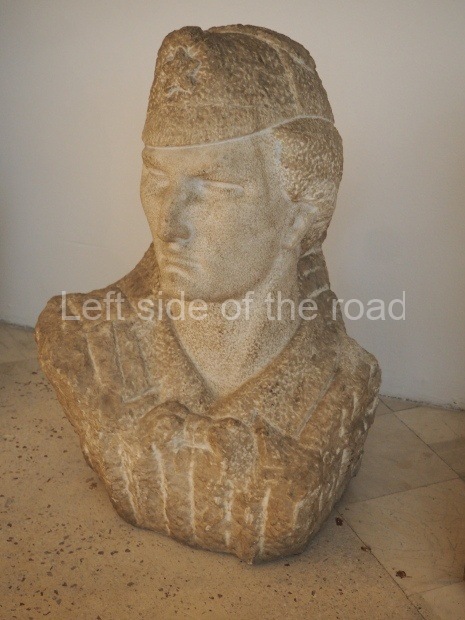

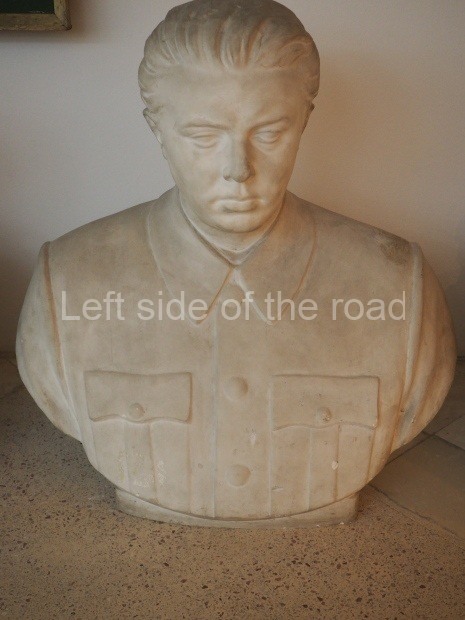

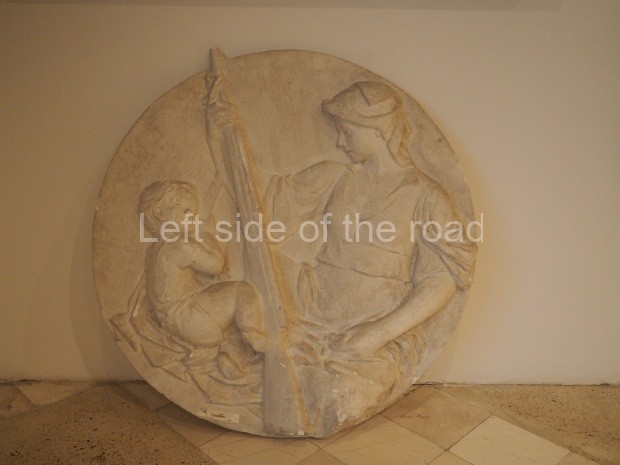

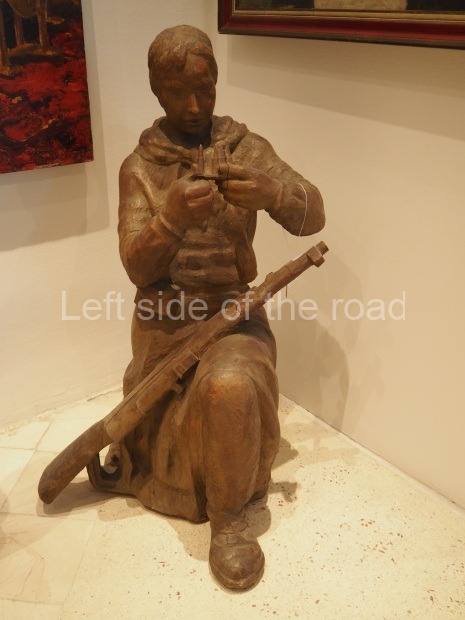

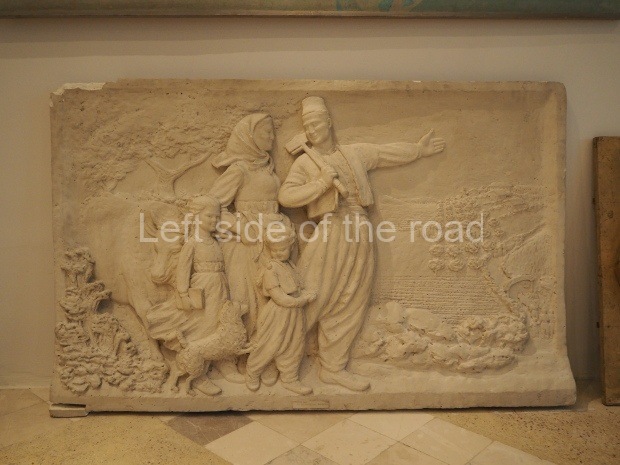

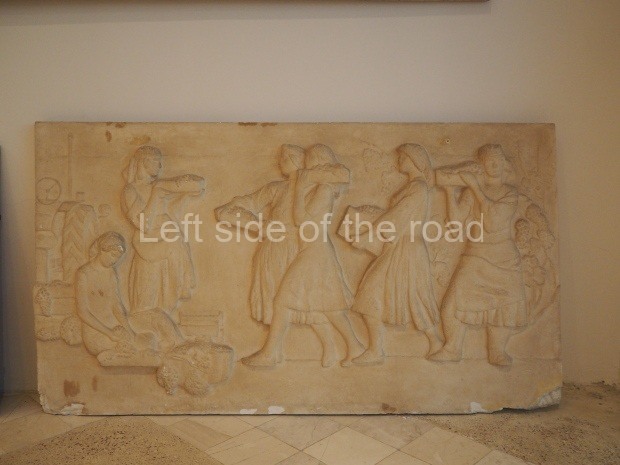

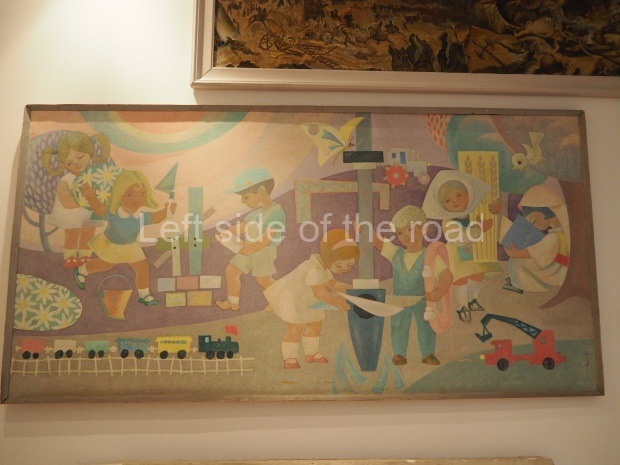

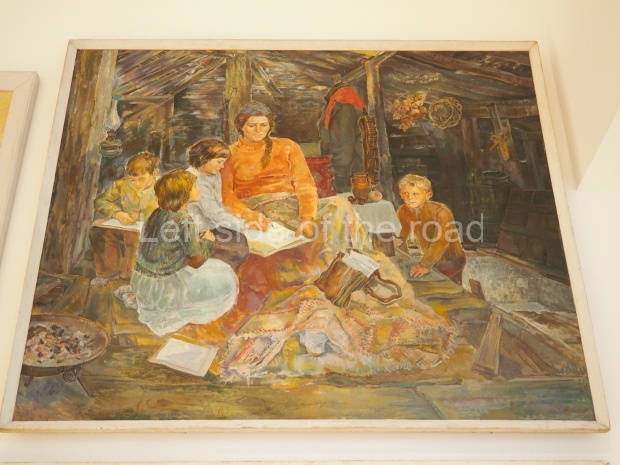

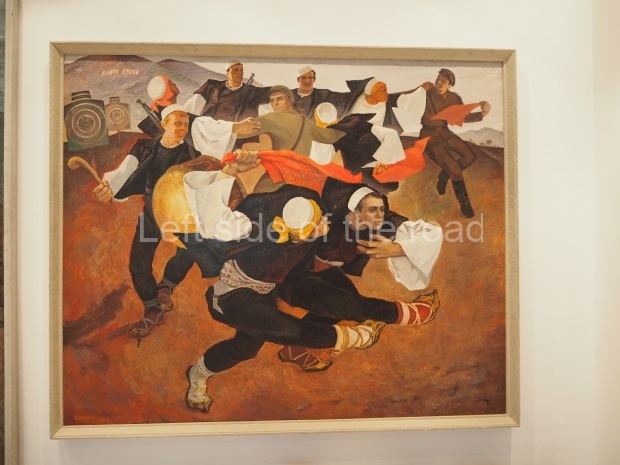

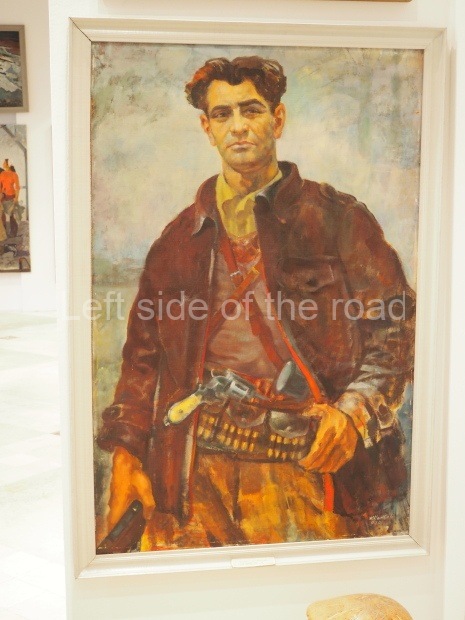

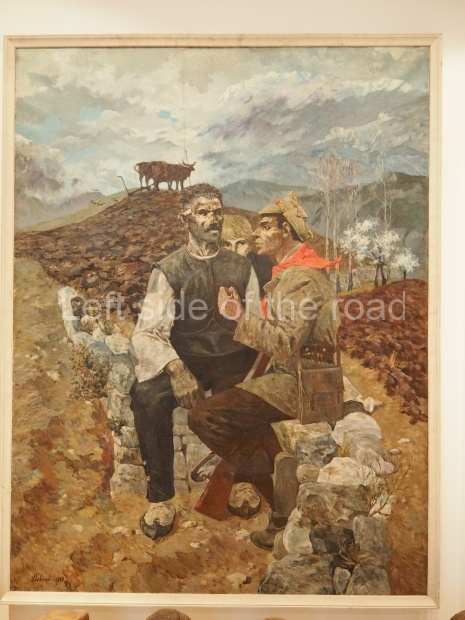

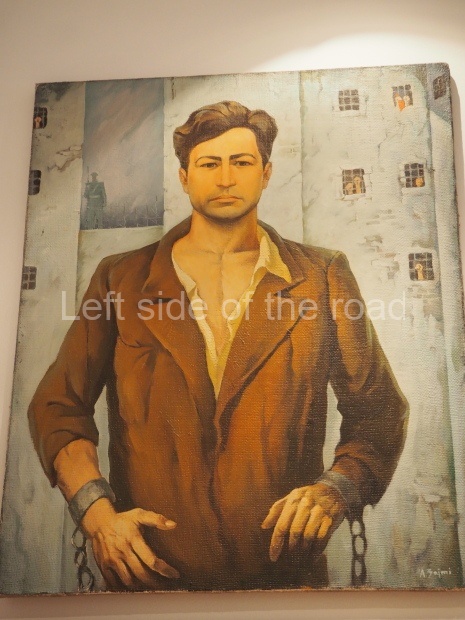

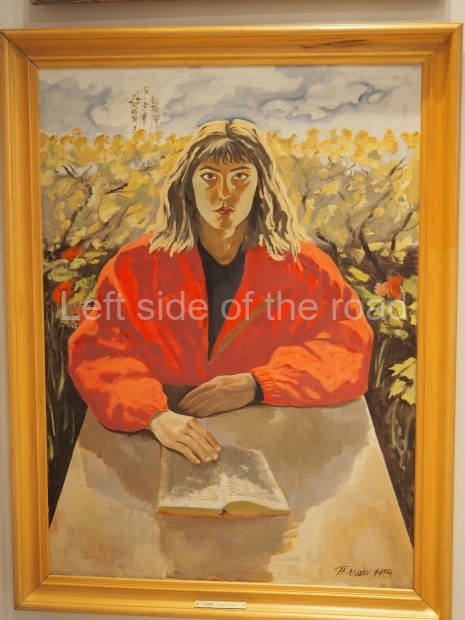

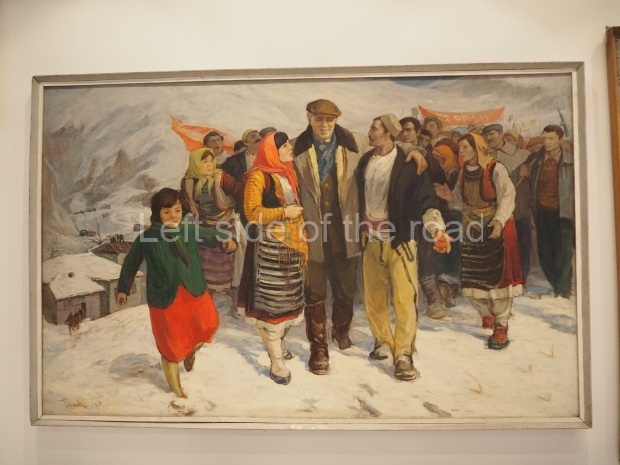

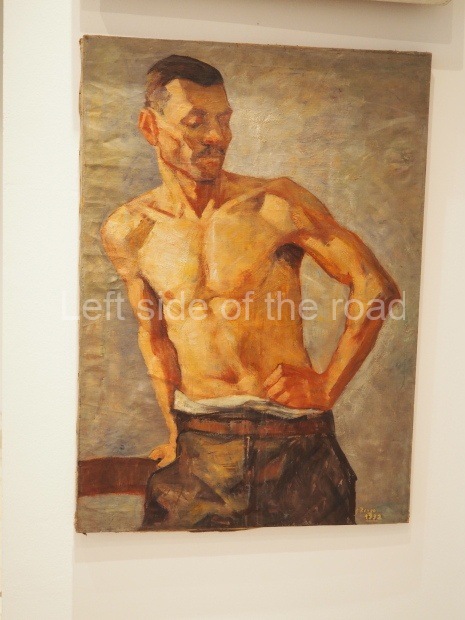

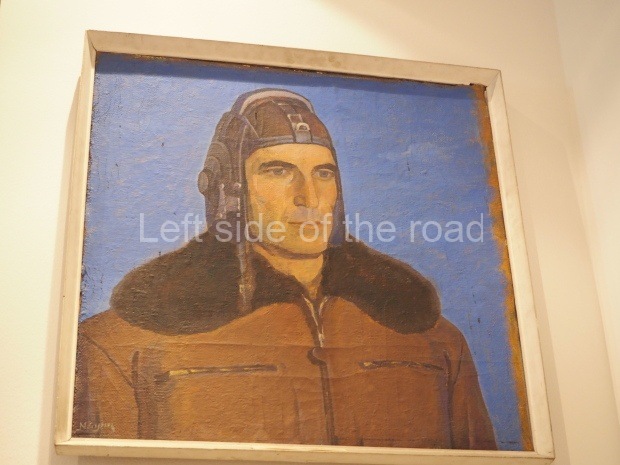

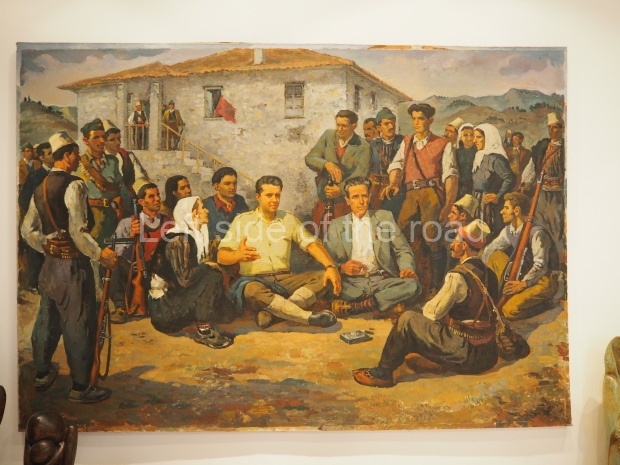

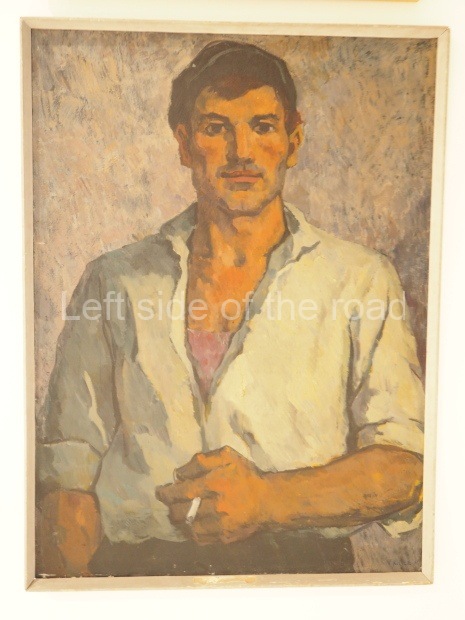

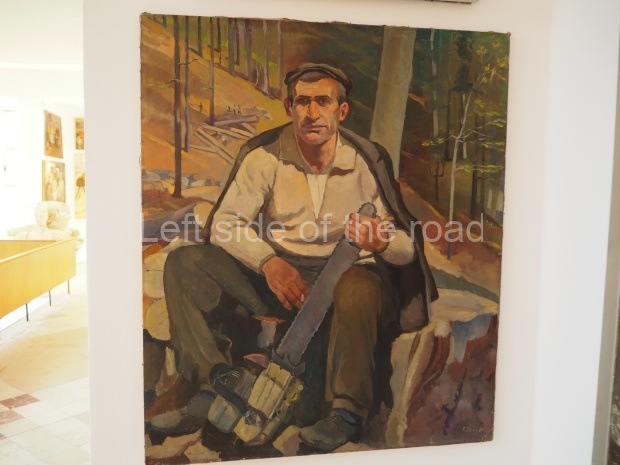

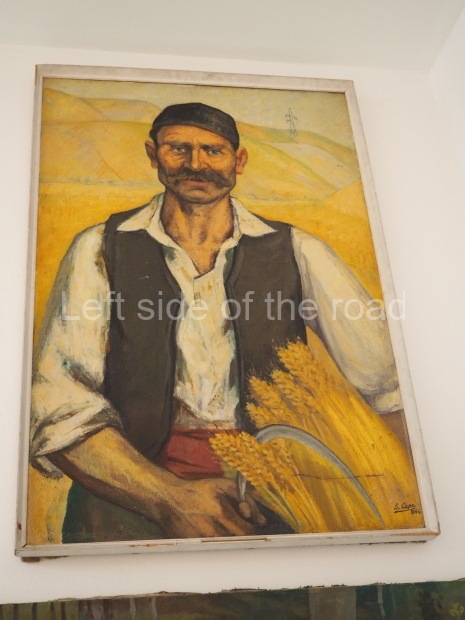

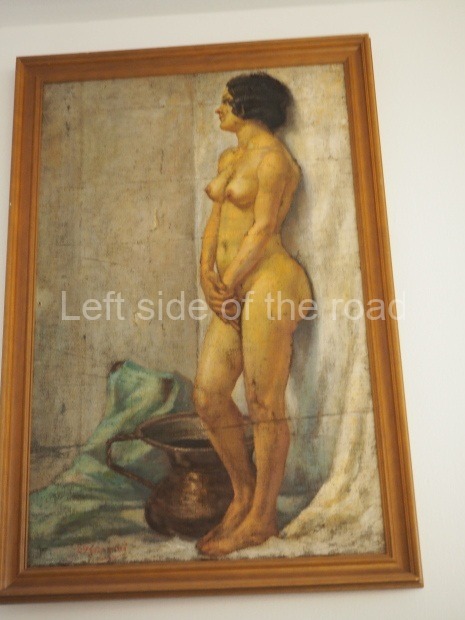

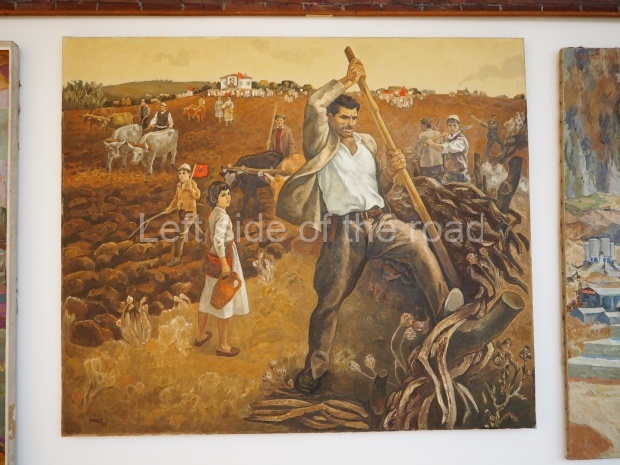

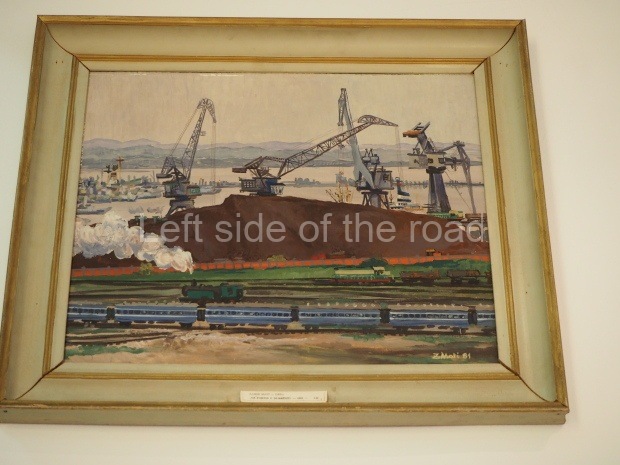

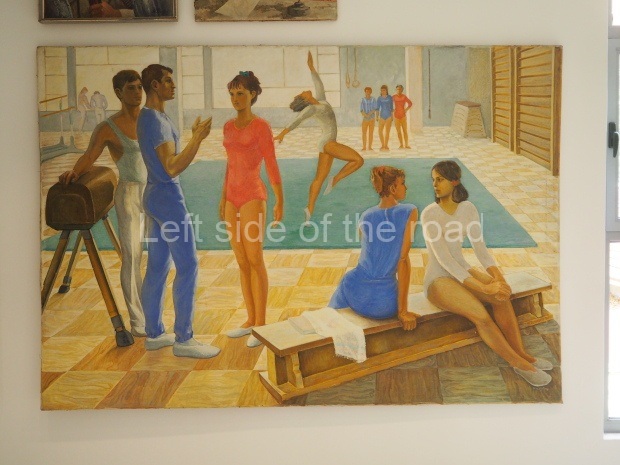

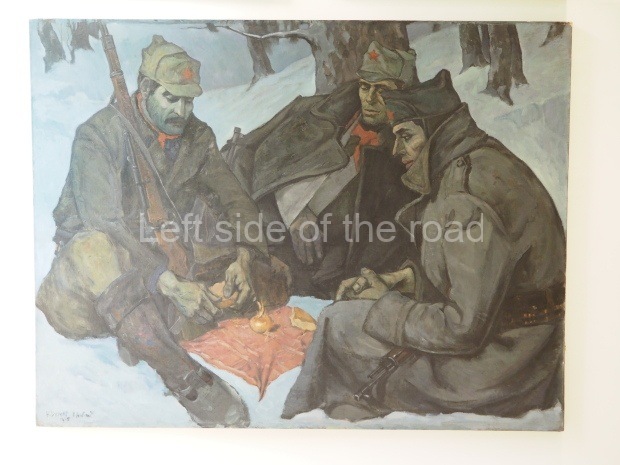

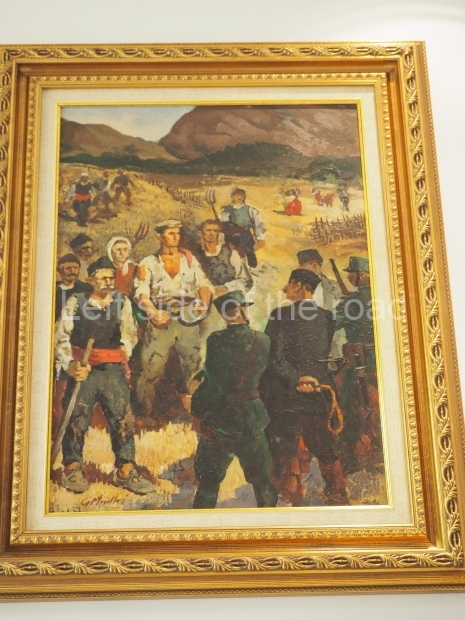

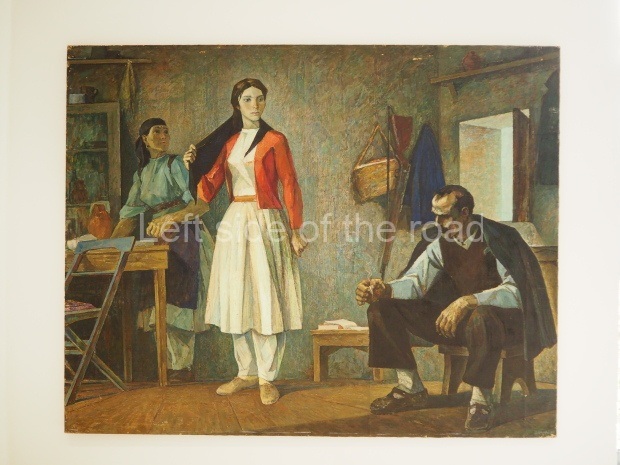

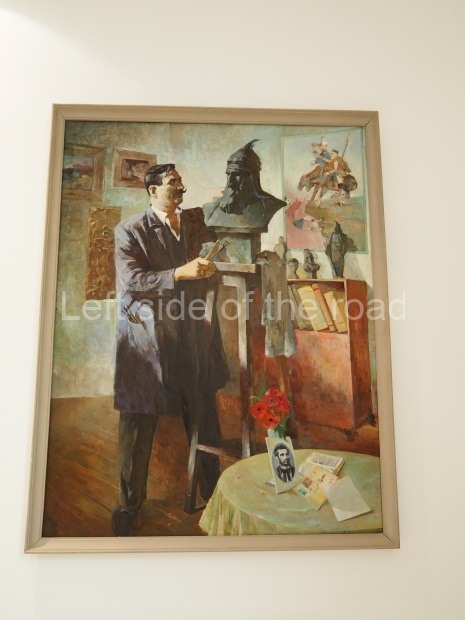

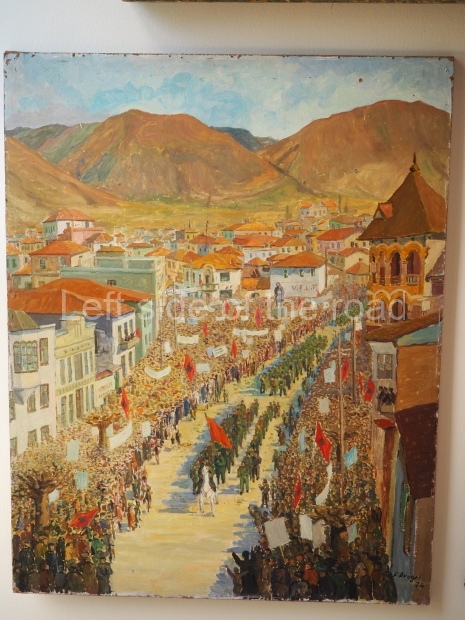

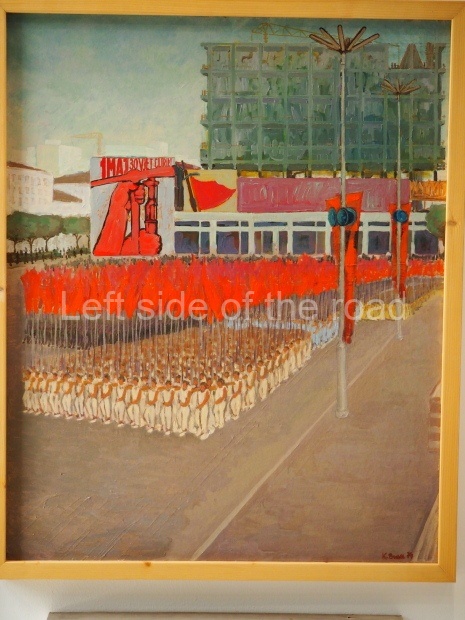

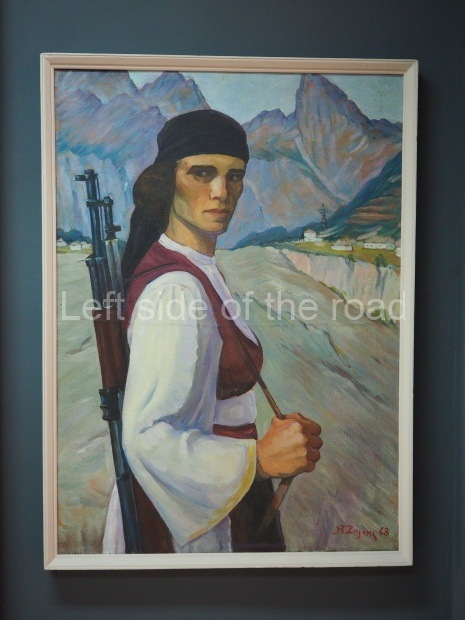

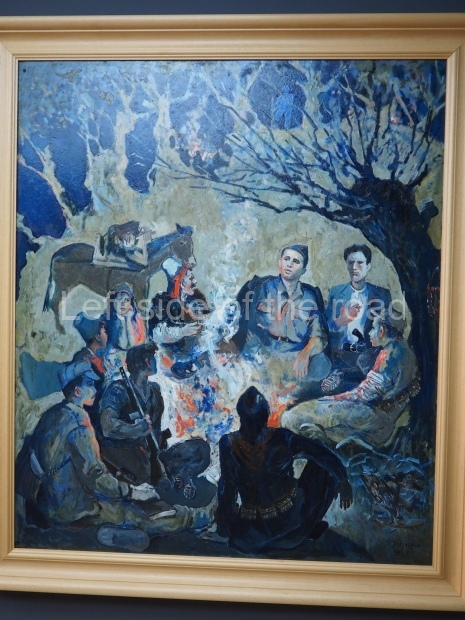

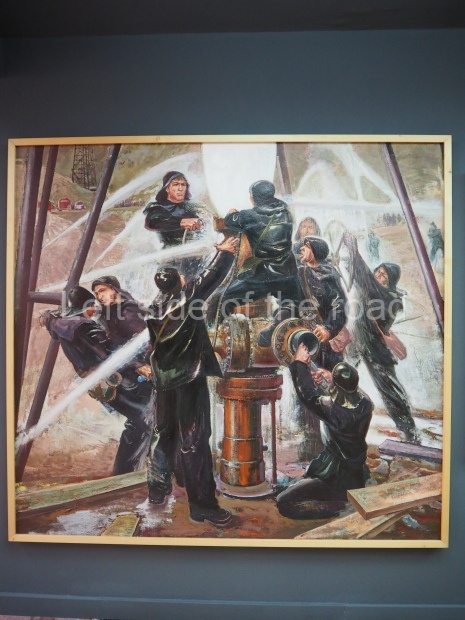

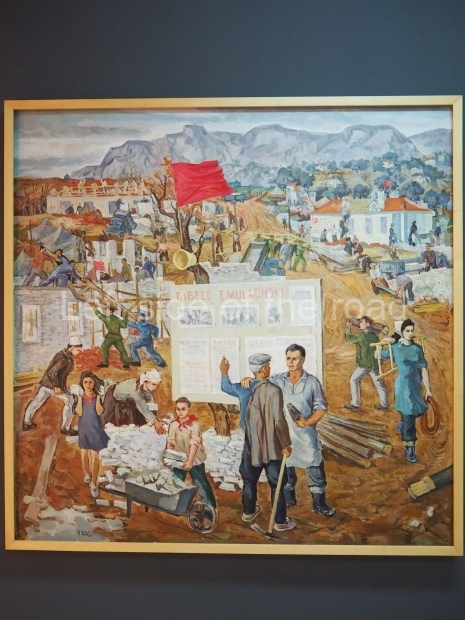

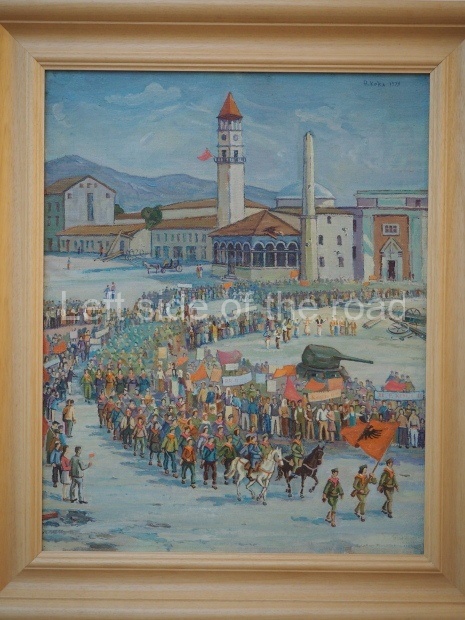

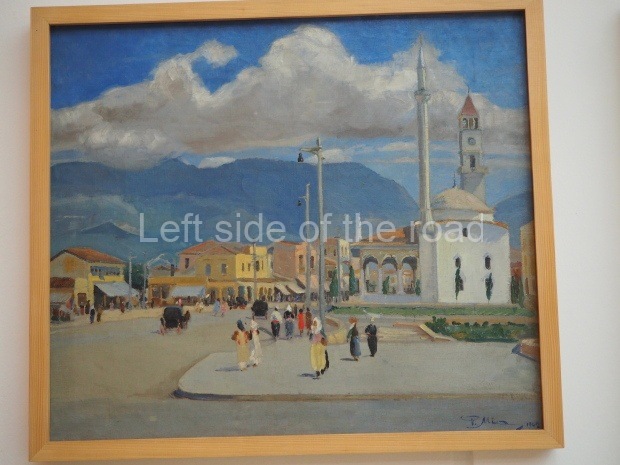

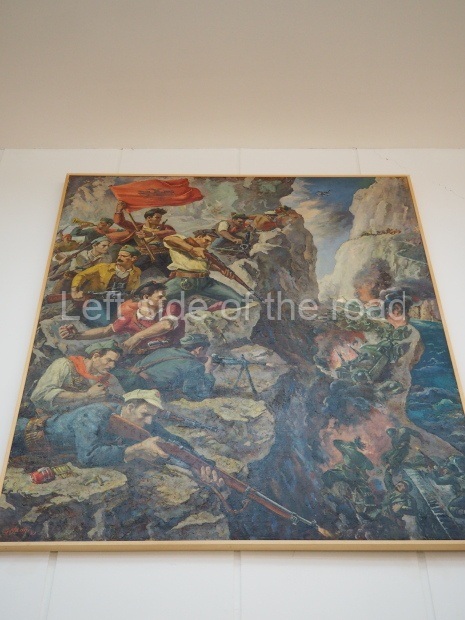

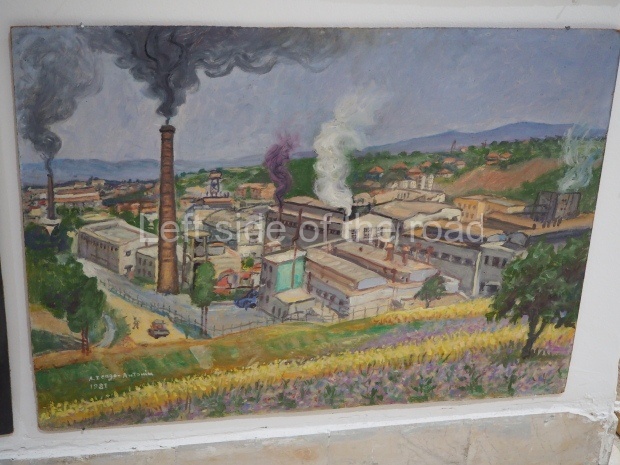

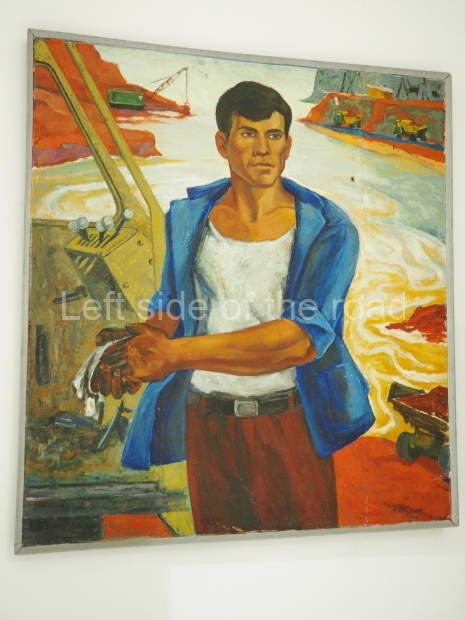

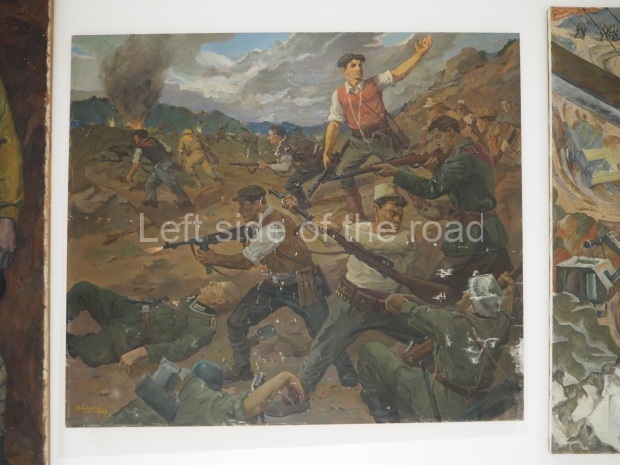

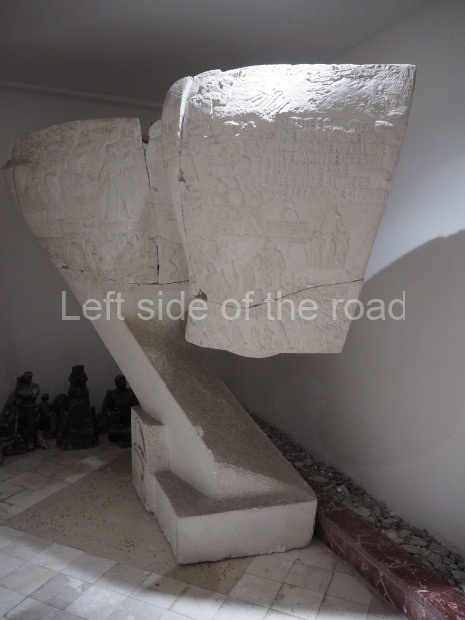

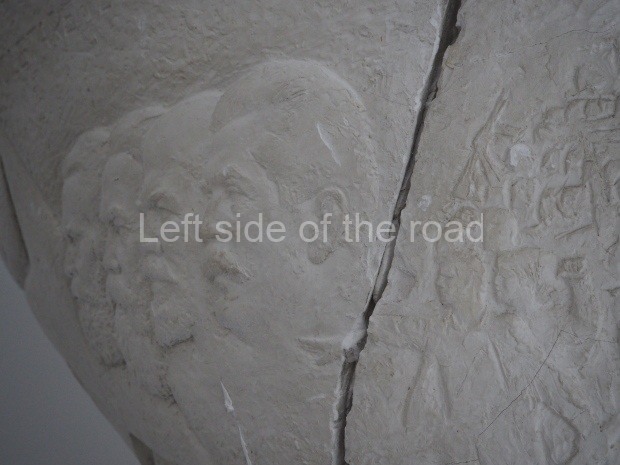

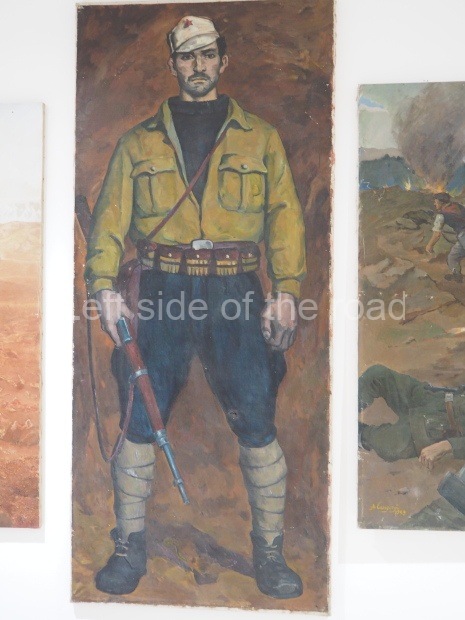

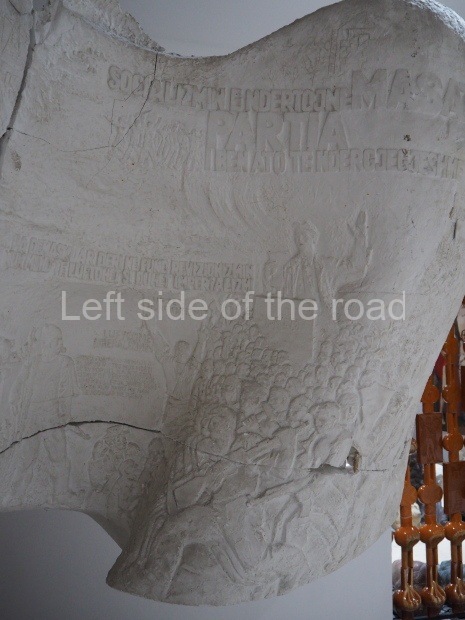

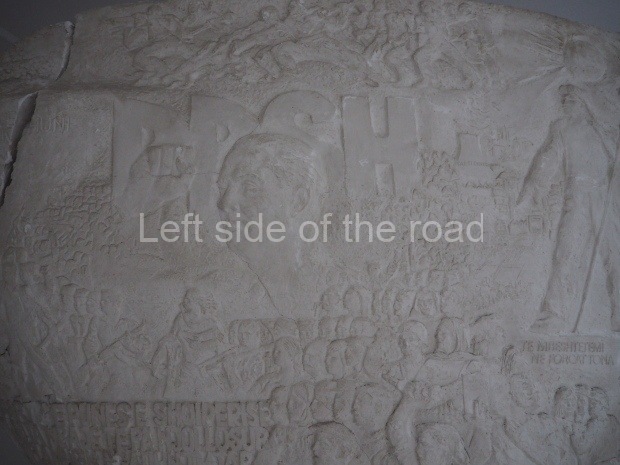

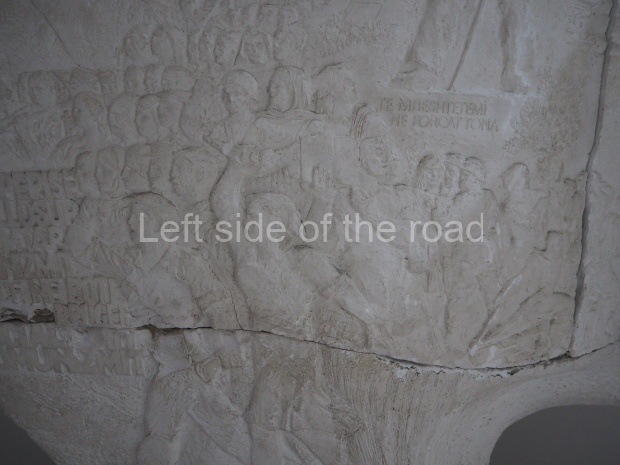

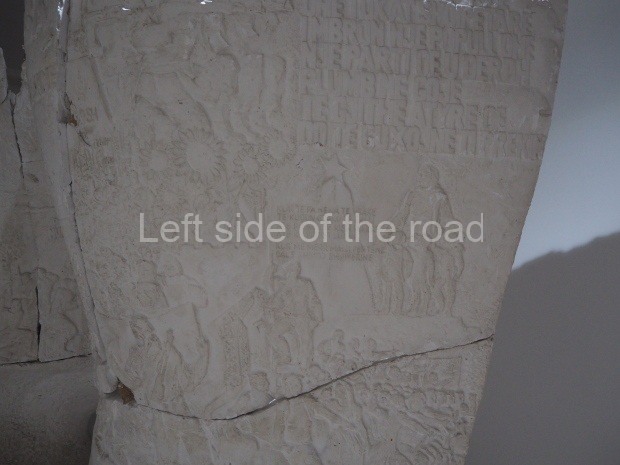

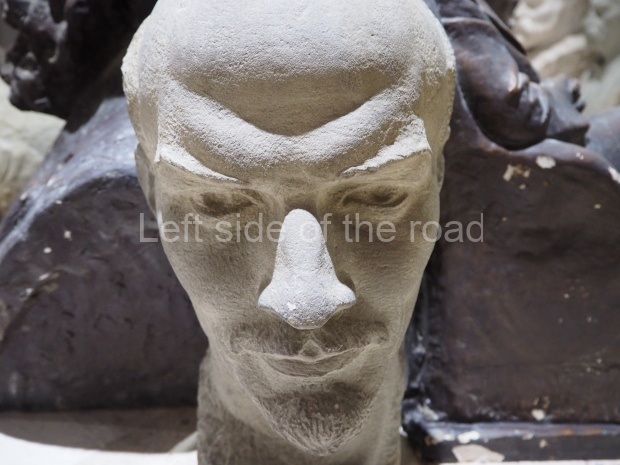

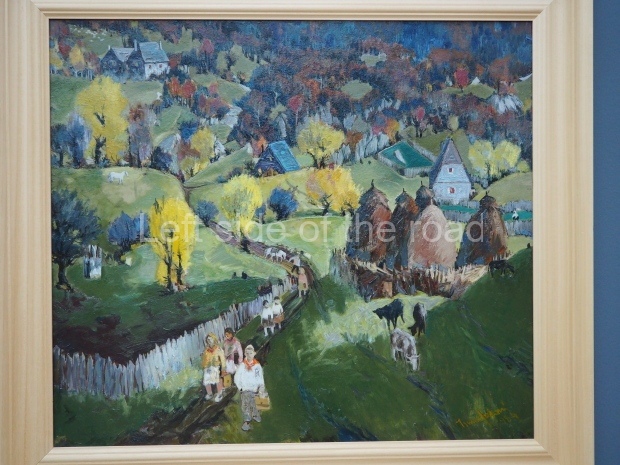

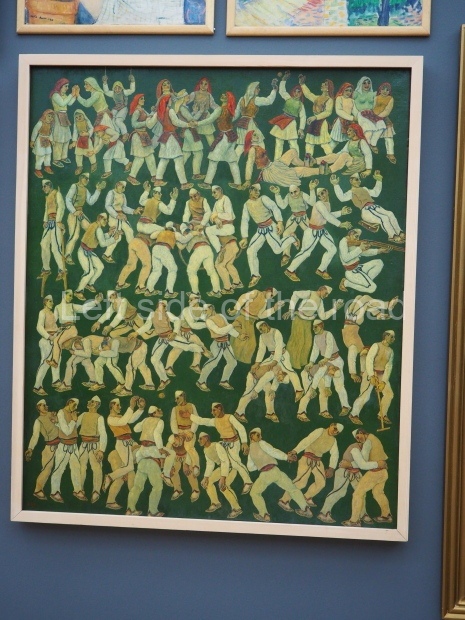

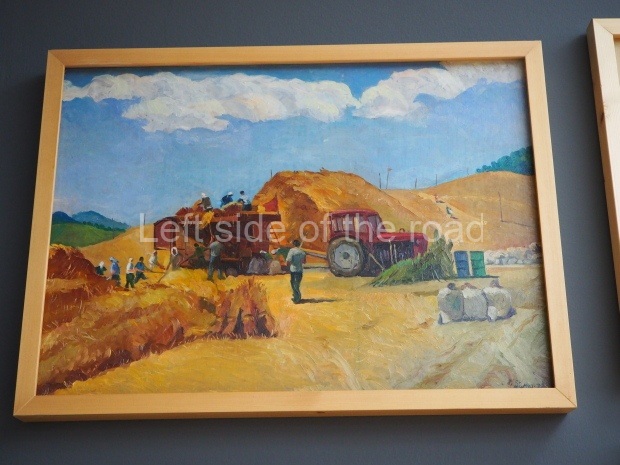

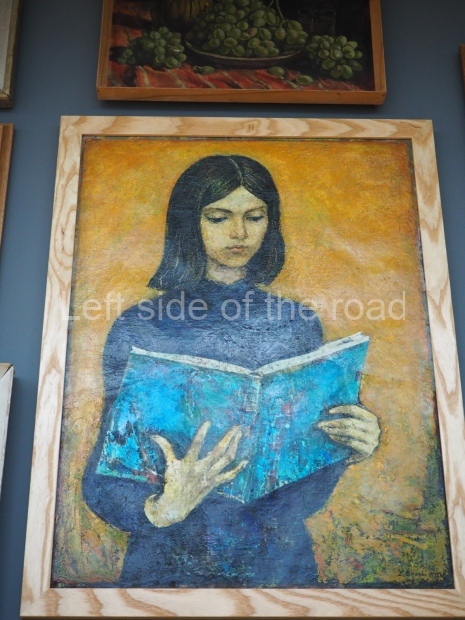

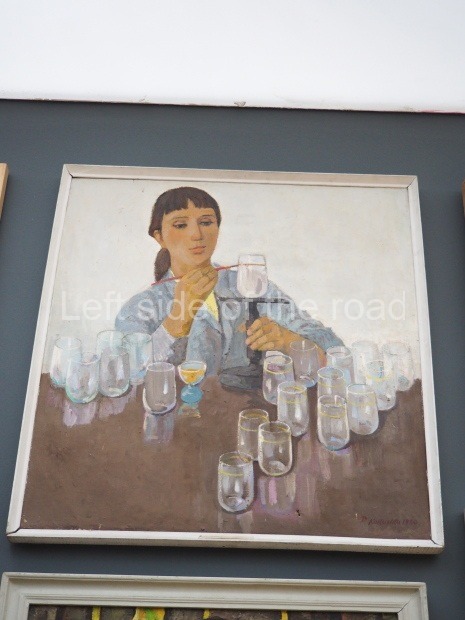

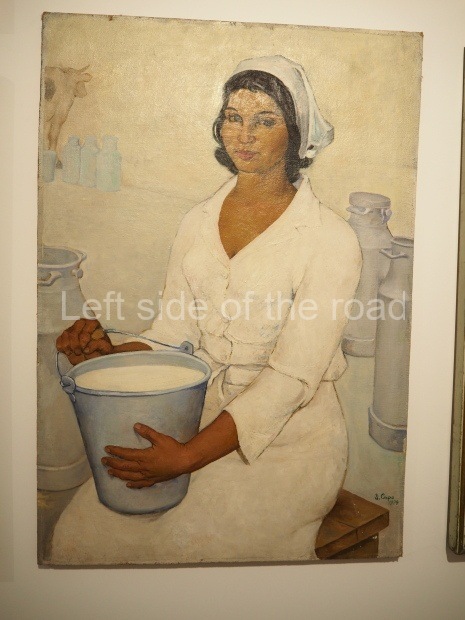

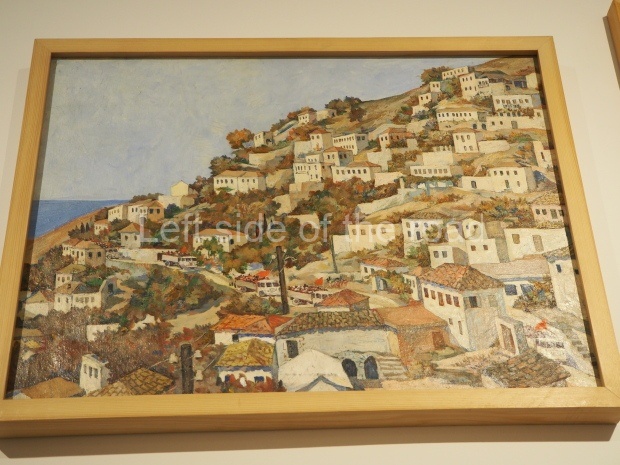

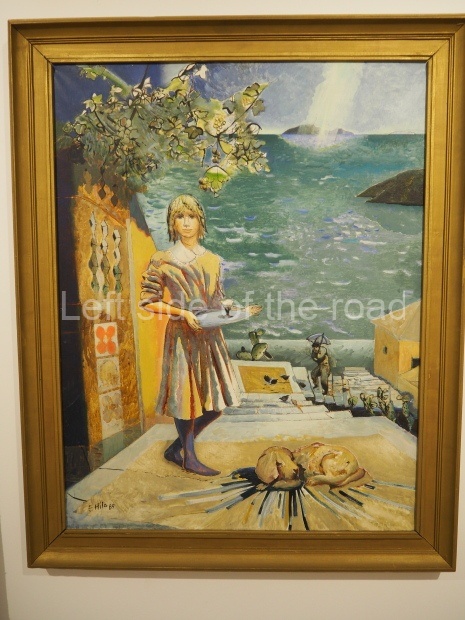

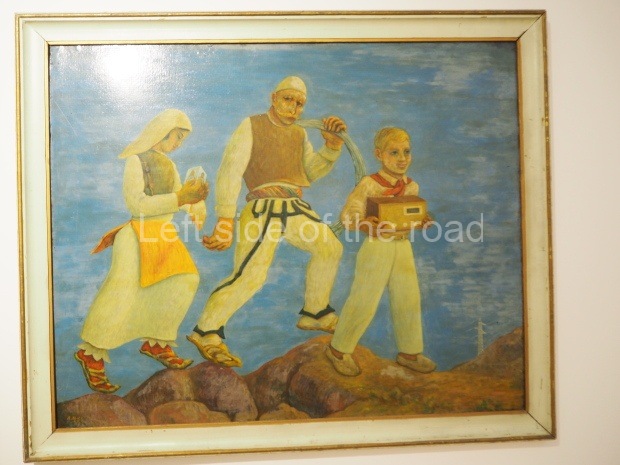

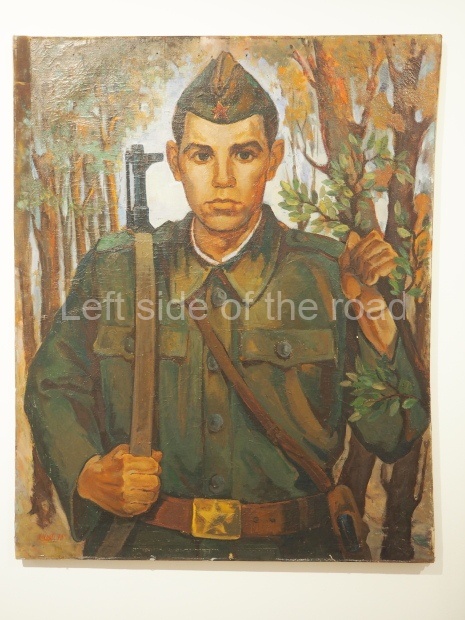

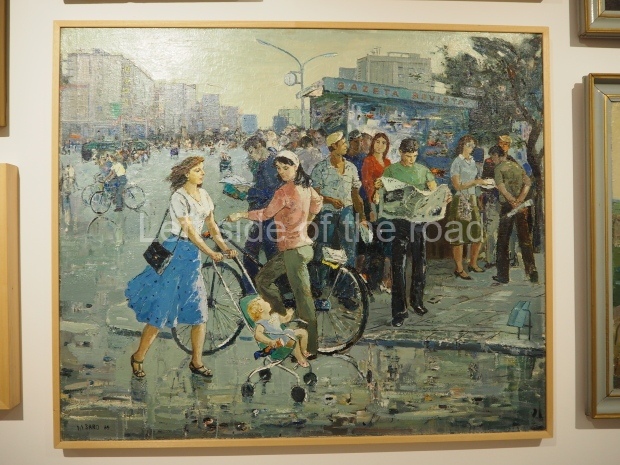

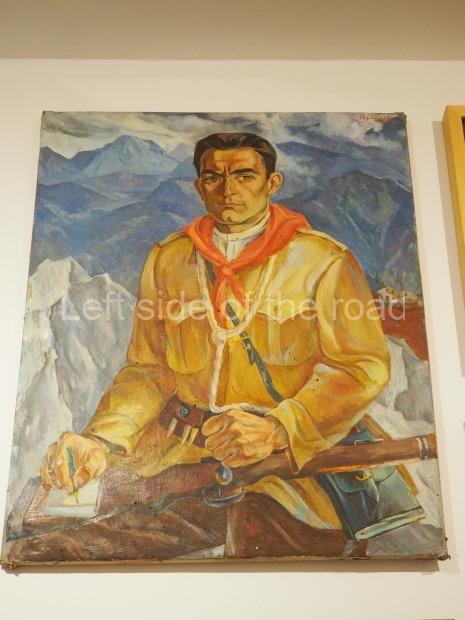

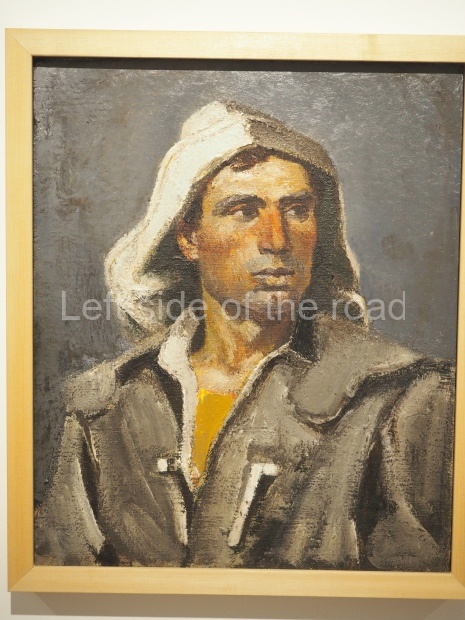

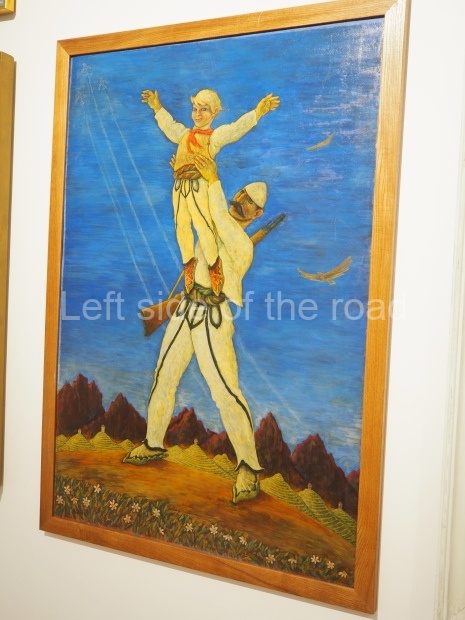

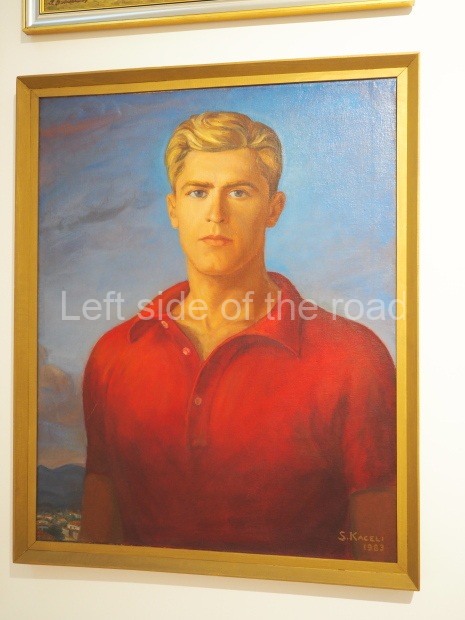

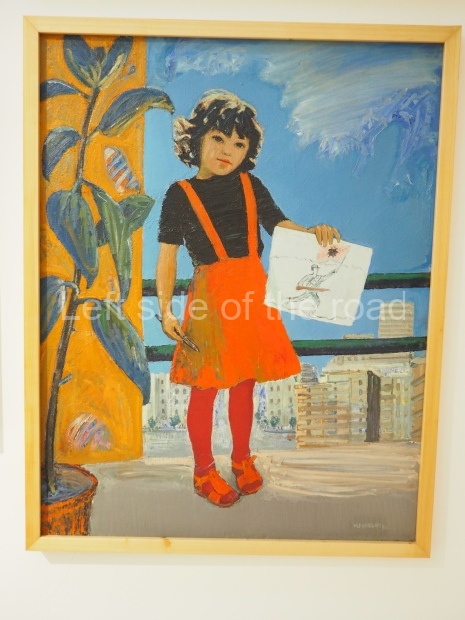

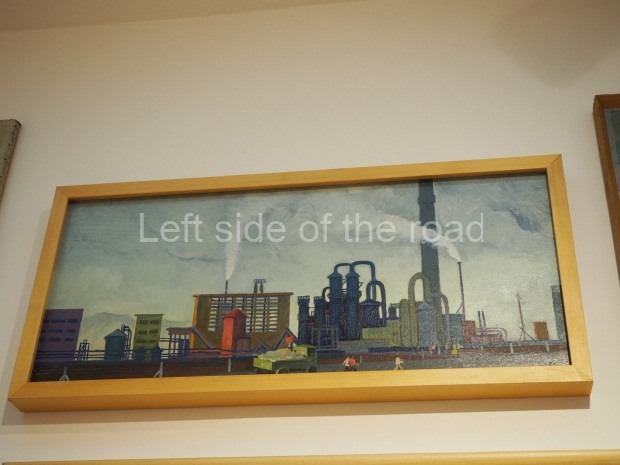

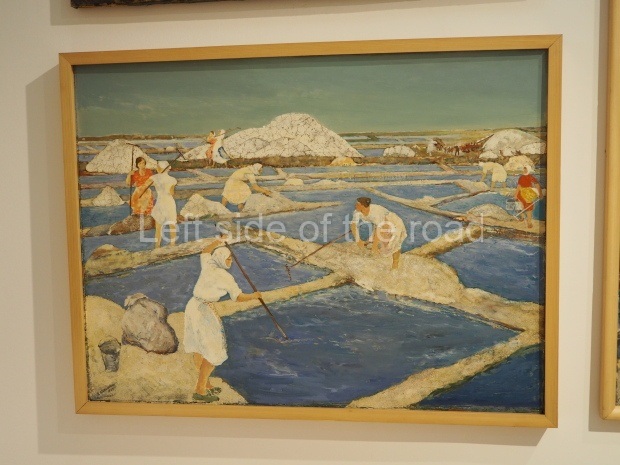

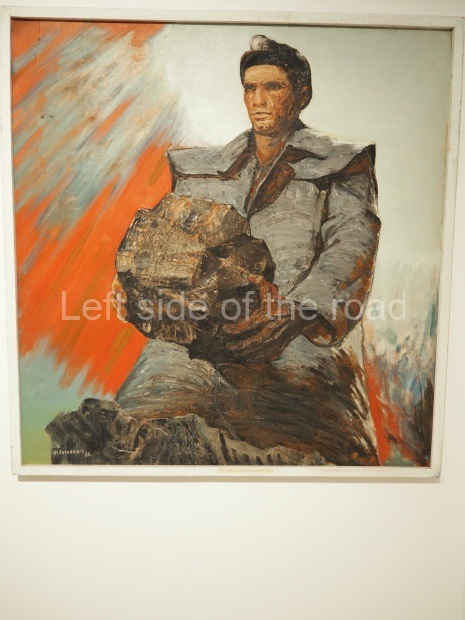

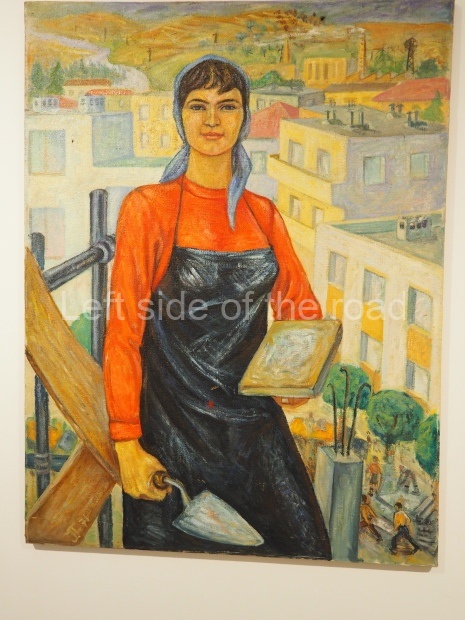

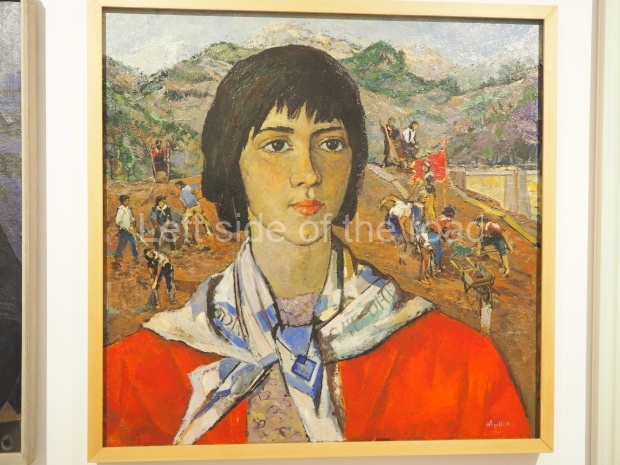

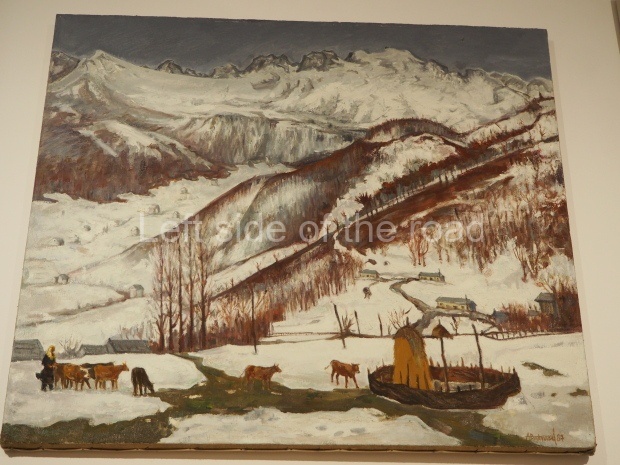

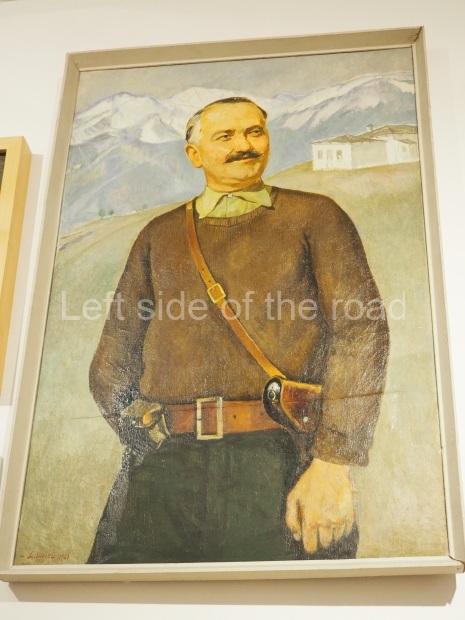

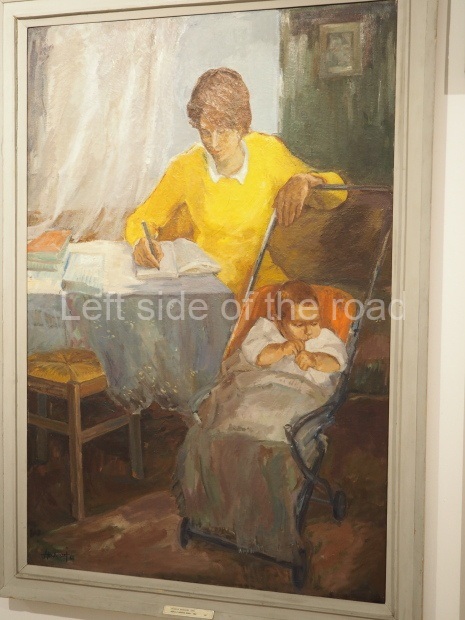

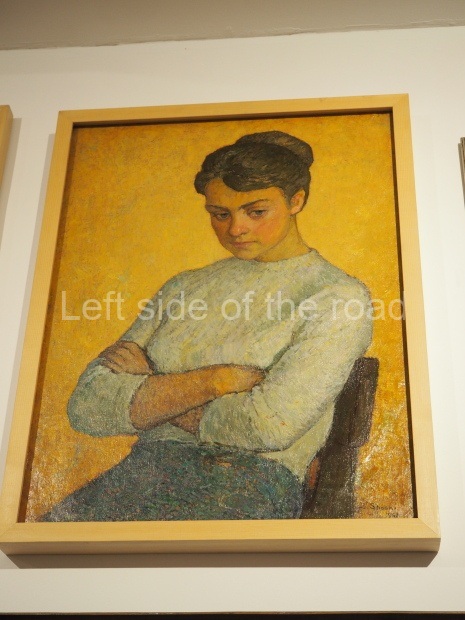

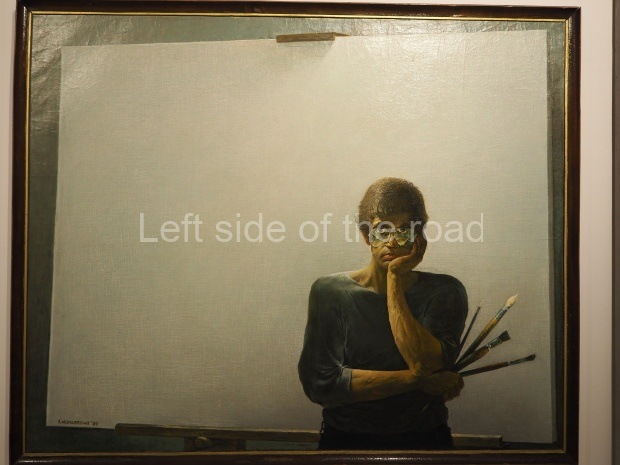

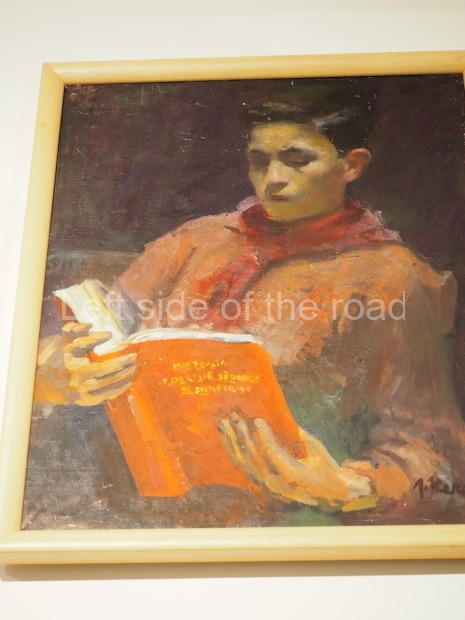

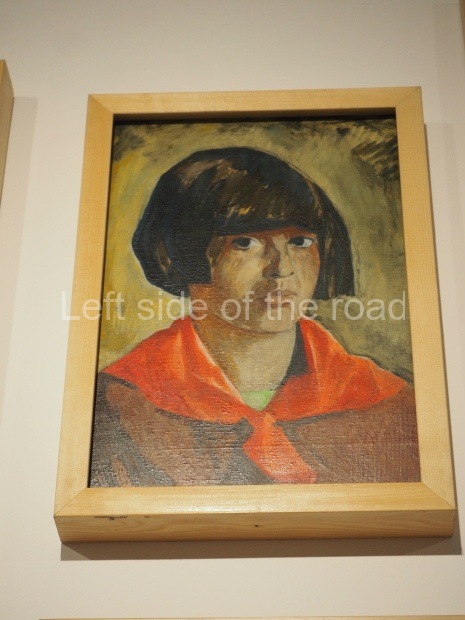

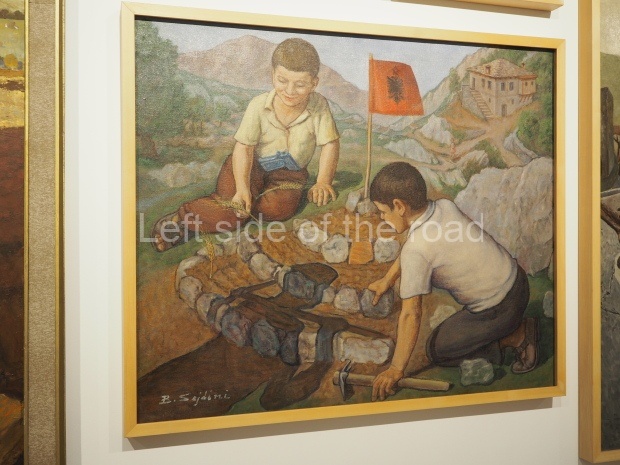

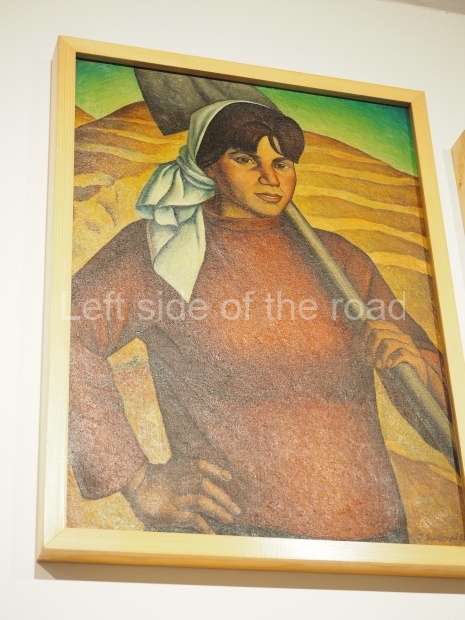

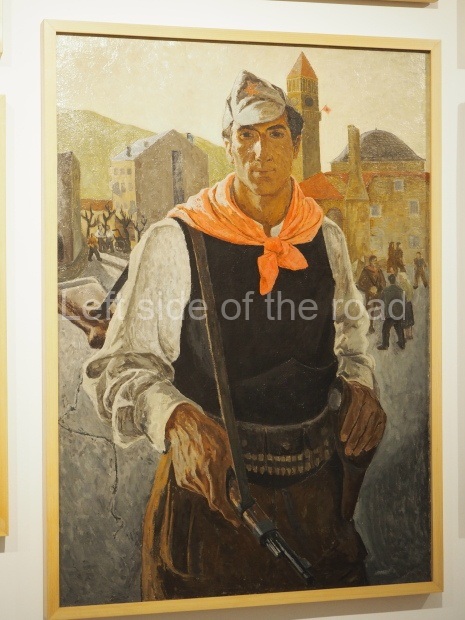

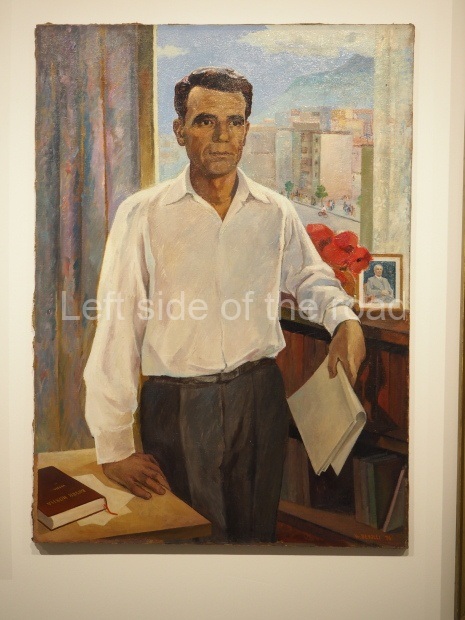

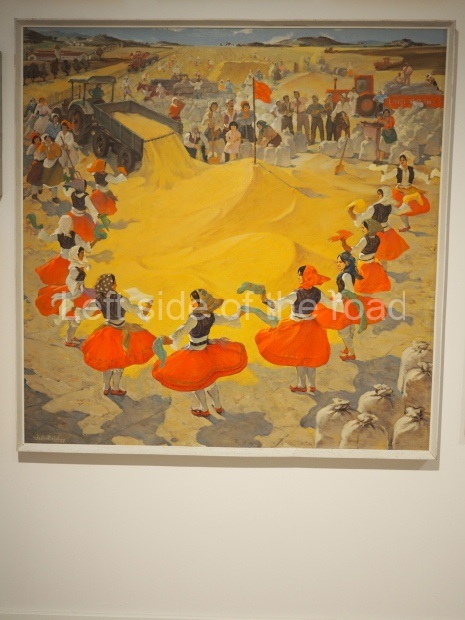

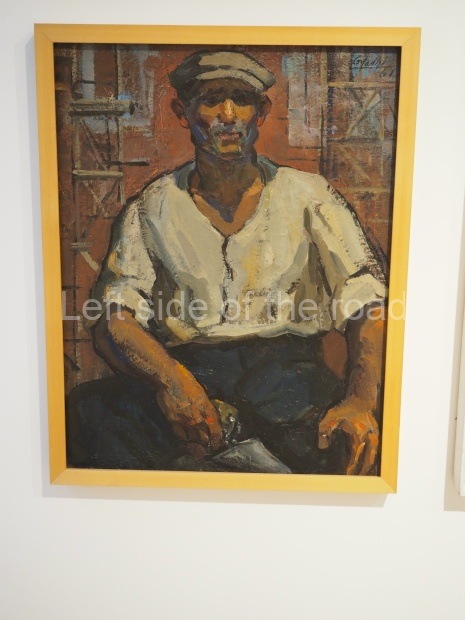

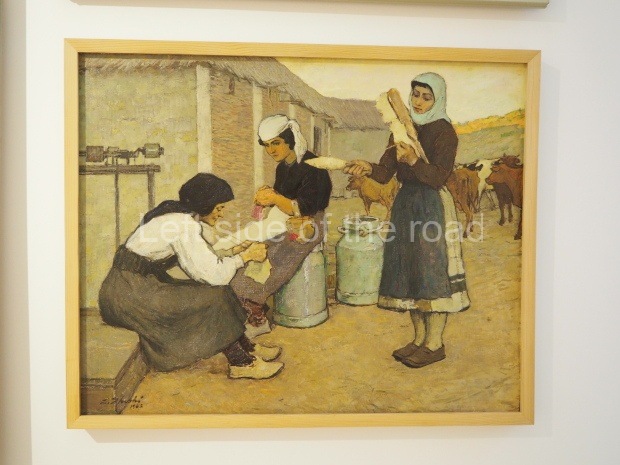

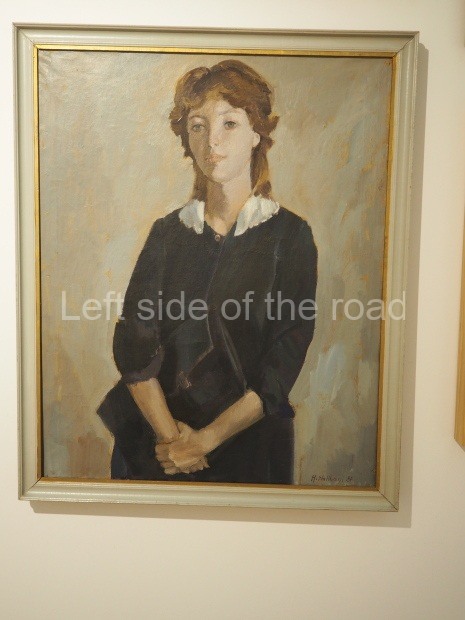

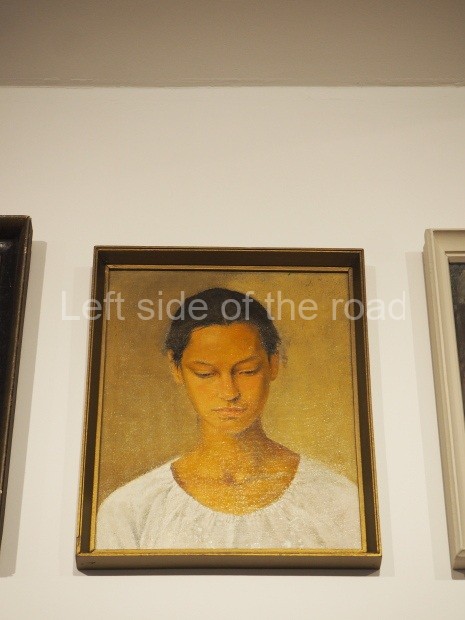

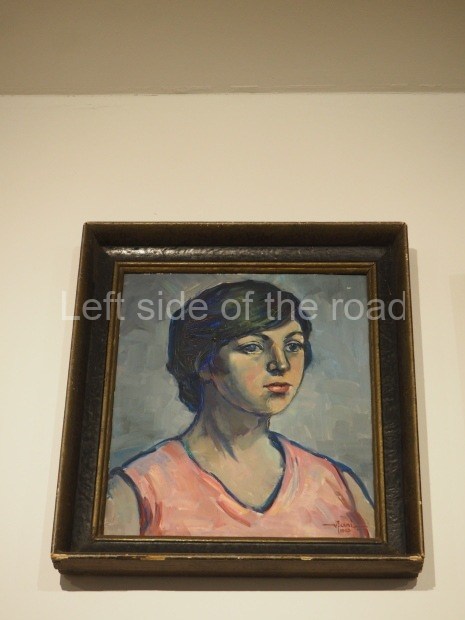

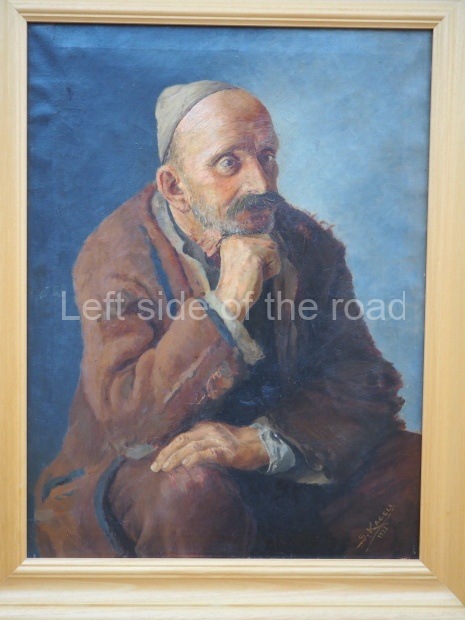

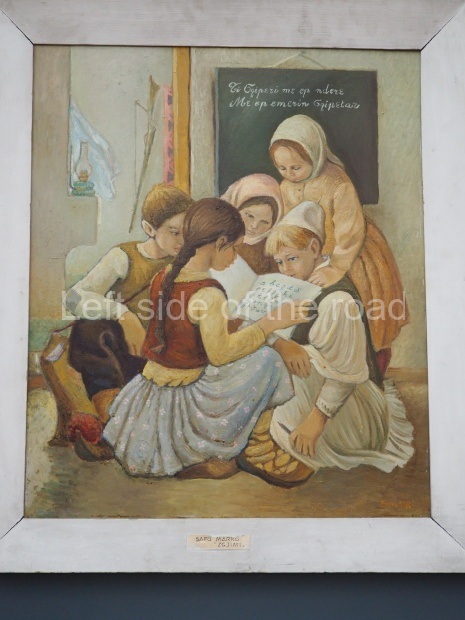

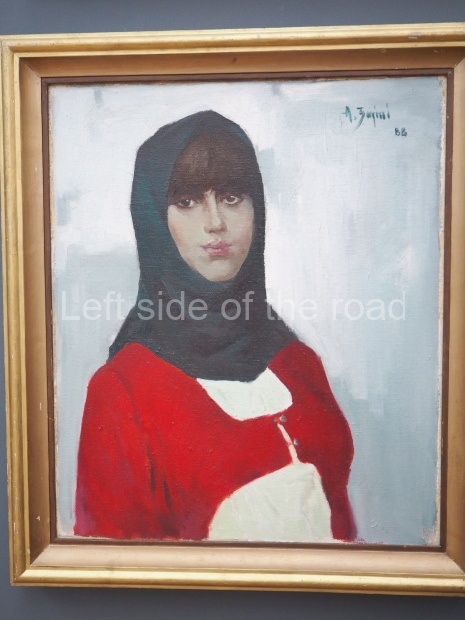

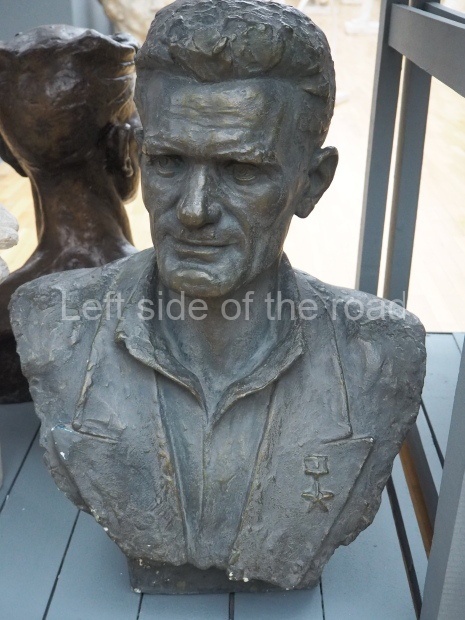

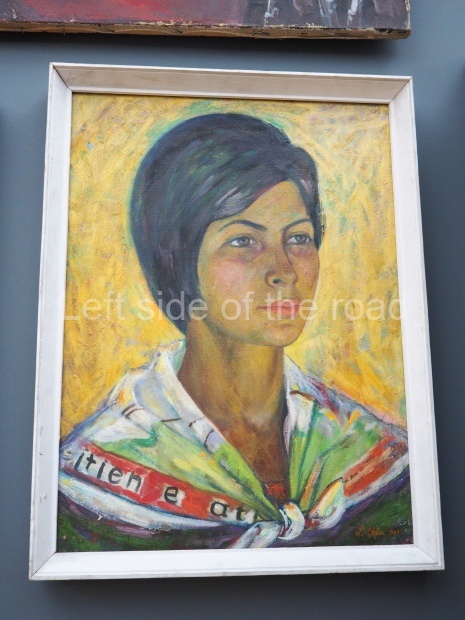

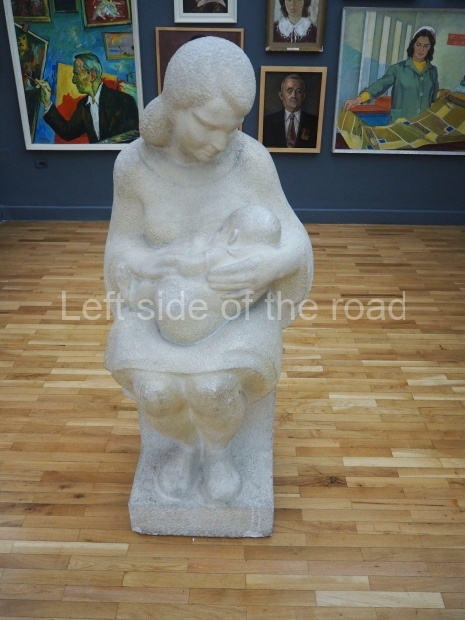

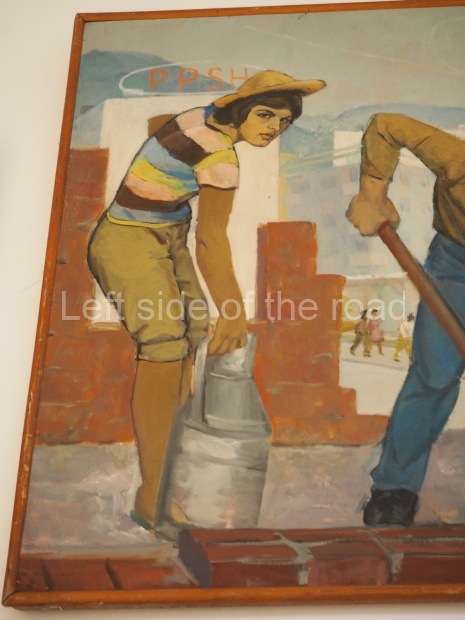

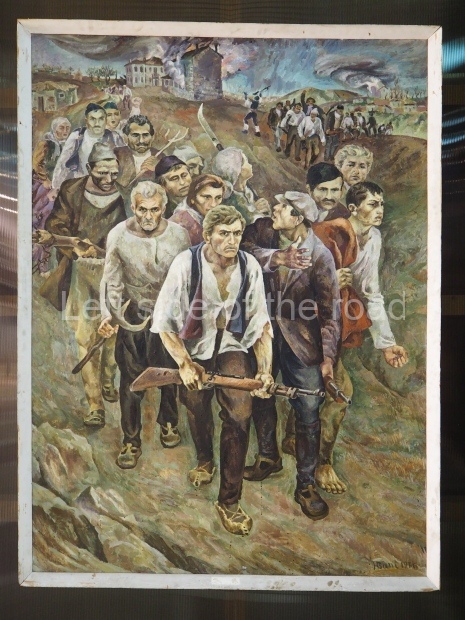

This was the role of the development of the Socialist Realist movement in the arts and was demonstrated in an Albanian context with the construction of the lapidars (which commemorated the past victories and sacrifices of the working people of the country against foreign invaders for national liberation as well as the achievements in the construction of Socialism).

Although the thinking in the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania was the same as that in the People’s Republic of China the way the cultural revolution manifested itself in the late 1960s was not the same – due to the different experiences in both countries.

Many people will be aware of The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (under the leadership of Chairman Mao) and the mass demonstrations and movements that took place in China from 1966 but that doesn’t mean to say the struggle didn’t exist in Albania. The same enemies, both internal and external, had to be confronted in both countries. Those countries, and parties worldwide, that aligned themselves with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union – after the success of Revisionism following the death of Comrade Stalin in 1953 – had failed to initiate this ‘cultural revolution’ and therefore started to follow the capitalist road. They had failed to learn from what Lenin and Stalin had taught.

All Marxist-Leninists who are seeking to established a Socialist state (under the dictatorship of the proletariat) need to study the writings of all the great Marxist theoreticians to ensure that any gains they might make in the future don’t get squandered amongst the euphoria that accompanies the success of the revolution. Capitalism never will rest to regain what it might have lost.

You might also be intested in The Socialist Cultural Revolution and the People’s National Culture.

Report to the Fifth Congress – 1st November 1966

THE FURTHER DEEPENING OF THE IDEOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION

The further revolutionisation of life in our country is inconceivable without the further development and deepening of the ideological and cultural revolution. It is accomplished precisely on the basis of this revolution, the fundamental aim of which is to instil and ensure the complete triumph of the proletarian socialist ideology in the consciousness of all the working people, while thoroughly eradicating the bourgeois ideology, to ensure the all-round revolutionary, communist education and tempering of the new man – the decisive factor in solving all the big, complicated problems of the construction of socialism and the defence of the Homeland.

Throughout its whole existence, our Party has devoted special care and attention to the all-round revolutionary education of the communists and all the working people. Especially since the 4th Congress [Report delivered on 13th February 1961, Enver Hoxha, Selected Works, Volume 3, pp192-283] and on the basis of its directives, our Party has done more persistent work in this direction.

1 – THE STRUGGLE FOR THE TRIUMPH OF THE SOCIALIST IDEOLOGY IS A STRUGGLE FOR THE TRIUMPH OF SOCIALISM AND COMMUNISM

In our country the proletarian socialist ideology is the ideology in power which sets the general tone for all the life and activity of our working people. Despite the successes achieved, however, we are conscious that the struggle in this field is protracted and difficult. V.I. Lenin said;

‘Our task is to overcome all the resistance of the capitalists, not only their military and political resistance but also their ideological resistance, which is the strongest and most deeply entrenched.’ VI Lenin, Collected Works, Volume 29.

The old idealist ideology of the exploiting society still has deep roots and exerts a powerful and continuous influence. When we speak of this influence, it is not just a matter of ‘a few remnants and alien manifestations that appear here and there’, as it is often wrongly described in our propaganda, but the influence of a whole alien ideology which is expressed in all sorts of alien concepts, customs and attitudes, which are retained for a long time as a heritage from the past, have social support in the former exploiting classes and their remnants, in the tendencies to petty-bourgeois spontaneity, and are nurtured in various forms by the capitalist and revisionist world which surrounds us.

As long as the complete victory of the socialist revolution in the field of ideology and culture has not been ensured, the achievements of the socialist revolution in the political and economic fields cannot be secure and guaranteed, either. Therefore, in the final analysis, the struggle on the ideological front for the complete defeat of bourgeois and revisionist ideology has to do with the question: will socialism and communism be built and the restoration of capitalism be avoided, or will the door be opened to the spread of bourgeois and revisionist ideology and the return to capitalism be permitted.

The ideological and cultural revolution is a part of the general class struggle to carry the socialist revolution through to the end in all fields. Contrary to the views of the modem revisionists, who have declared the class struggle in socialism outdated and a thing of the past, our Party holds that class struggle remains one of the main motive forces of society, even after the exploiting classes have been eliminated. This struggle includes all fields of life. It has its ebbs and flows and zigzags, sometimes it surges up, sometimes it falls back, sometimes becomes fierce, at other times more ‘mild’, but it never ceases and dies right away.

As the experience of our country shows, this struggle is an objective and inevitable phenomenon in socialism. It is waged against the remnants of the exploiting classes, overthrown and expropriated, but who continue to resist and exert pressure by every means, first and foremost, through their reactionary ideology, as well as against new bourgeois elements, degenerate revisionist and anti-Party elements, who inevitably emerge within our society. It is also waged against bourgeois and revisionist ideology which is retained and expressed in various forms and degrees of intensity, as well as against the external pressure of imperialism. Thus the internal and external fronts of class struggle are interconnected, now merging into one single front, now operating separately, but always linked by the same objective: to overthrow the dictatorship of the proletariat and restore capitalism.

Acceptance or non-acceptance of the class struggle in socialism is a question of principle, it is a line of demarcation between Marxist-Leninists and revisionists, between revolutionaries and betrayers of the revolution. Any deviation from the class struggle has fatal consequences for the future of socialism. Therefore, along with the struggle to increase production, to develop education and culture, along with the struggle against foreign enemies – the imperialists and revisionists, we must not neglect, must never overlook the class struggle within the country, for otherwise history will punish us severely.

The duty of the Party is not to shut its eyes to this necessity, not to benumb the revolutionary vigilance of the communists and masses, but to wage this class struggle vigorously and unwaveringly until final victory. The progress of our society and the revolutionary education of the working people are inconceivable and cannot be achieved outside the class struggle.

In practice we often come across a narrow concept on the class struggle and class enemy, which regards only the kulaks and other elements of the former exploiting classes, or the imperialists and Titoite and Khrushchevite revisionists abroad as class enemies, and only the struggle against their anti-socialist activities as class struggle. The struggle against these enemies remains, as always, a primary task for our Party, our state and our working people. But we should take a broader view of the class struggle. It is a many-sided struggle which is, first and foremost, an ideological struggle today, a struggle for the minds and hearts of people, a struggle against bourgeois and revisionist degeneration, against all alien remnants and phenomena which still exist and manifest themselves in various degrees among all our people – it is a struggle for the triumph of our communist ideology and morality.

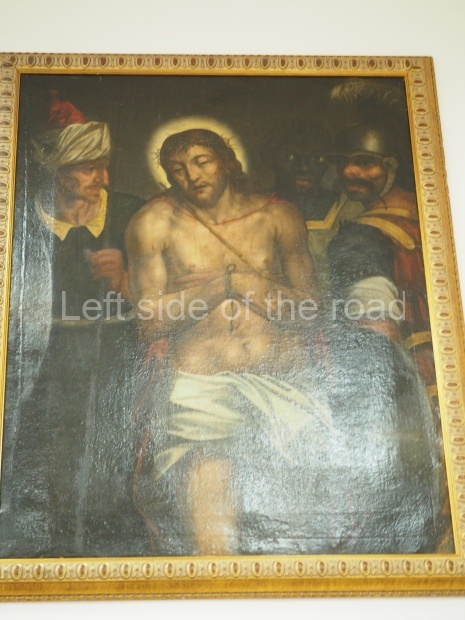

The struggle against theft and misuse of socialist property, against parasitic and speculative tendencies to take as much as possible from society and to contribute to it as little as possible, against putting personal ease, the personal interest and glory above the general interest, against bureaucratic manifestations and distortions, religious ideology, prejudices, superstitions and backward customs, against underestimation of women and failure to respect their equal rights in society, against fashion and the bourgeois way of life, against idealism and metaphysics, against various ‘isms’ of the decadent bourgeois and revisionist art and culture, against the political and ideological influence of external enemies, etc., etc., all these things are parts of the class struggle.

Thus, the class struggle is not only directed against external and internal enemies, but is also waged within the ranks of the working people, against any alien manifestation observed in the consciousness, the thinking, the behaviour and the attitude of each individual. No one should think that he is proof against any evil and has nothing to fight against within himself. A stern struggle between socialist ideology and bourgeois ideology takes place in the consciousness of each person. Everybody ought to look at himself as though in a mirror and clean his consciousness every day, just as he washes his face every day, by taking a communist attitude towards himself.

Class struggle is reflected within the Party, too, because, on the one hand, people from different social strata come into the Party, bringing with them all kinds of alien remnants and manifestations, and on the other hand, the party members, like all the working people, encounter the pressure of the class enemy, especially of the enemy ideology, from inside and outside the country. Consequently, in the party ranks as well as in the ranks of the working people there may and do emerge people who degenerate and go over to alien anti-Party and anti-socialist positions. Moreover, in all their activities our enemies give particular importance to the degeneration of party members in order to bring about the degeneration of the Party as a whole, because only thus can the way be opened to the restoration of capitalism. It should be clear that without contradictions of various kinds and without a struggle to overcome them, the life and development of the Party would not be possible. This struggle should not he covered up under the pretext of preserving unity, but should be waged and carried through to the end, thus strengthening the true unity of the Party, its revolutionary spirit, its militancy and the dictatorship of the proletariat.

It is a primary task of all the ideological work of the Party to form a correct concept about class struggle in our country in all the communists and working people, to educate them in the spirit of irreconcilable class struggle, to instil in them the method of class analysis which is the only method by which to know and correctly solve all the problems, to teach them not only to accept the need for class struggle in words, but to wage it in all fields of life every day. This is not something new. Our Party has always stressed the need to wage the class struggle and carry out class education and has done a great deal of work in this direction.

We must fight indifference and formalism in our political work for the education of the Party and the masses and always link it properly with the active class struggle. We must resolutely combat alien concepts and manifestations opposed to the line of the Party and the interests of people and socialism, combat the tendency to avoid calling things by their true names, but to soften them and smooth them over, concealing their class essence and their social danger.

These shortcomings in the work of party organizations account for the fact that some cadres and party members do not always give priority to the common interests represented by the party policy, but often look at things from the angle of personal, local or departmental interest, look at various problems with the eye of a technocrat and bureaucrat, with the eye of a narrow-minded specialist and neglect the political and ideological aspects. They do not understand that there is politics everywhere, in every work and sector, because there are no cadres or economic, administrative, cultural or military work divorced from politics or outside the policy of the dictatorship of the proletariat. All things are interconnected and interdependent and in this unity politics occupies the main place, and likewise all our cadres, in every sector where they work, should be, first and foremost, political people, should put the policy of the Party first and always guide themselves by it.

Our Party has always been characterized by its stern irreconcilability with the enemies of the people, socialism and Marxism-Leninism and its love for and boundless loyalty to the working people and their revolutionary cause, its wisdom and patience with all those who commit mistakes but can be corrected. Narrow, sectarian attitudes have always been alien to it. Therefore, the party organizations must resolutely combat any manifestation of sectarianism in their work because this damages the links of the Party with the masses, confuses the dividing line between us and our enemies and leads to the use of wrong methods in resolving contradictions among the people, which affect the working people themselves.

The ideological work of the Party must make the nature of the contradictions in socialist society thoroughly clear, as well as the ways to resolve them correctly … Any mixing up of the two kinds of contradictions leads to opportunist and sectarian errors.

It must always be borne in mind that the carriers and spreaders of the bourgeois ideology are not only elements from former exploiting classes but also our own people who are working for the cause of socialism. In these cases, while fighting mercilessly against the disease, the alien ideology, we must strive with all our might to cure the patient, the carrier of that ideology. Only in the case when the carrier and spreader of the alien ideology is or becomes our conscious enemy, only then is the contradiction handled and resolved as an antagonistic contradiction and the method of persuasion replaced by that of compulsion. The Party must do a great prophylactic, educational and political work, patiently and systematically, to prevent anyone from falling into grave blunders, going from blunders to culpable faults and then to anti-state and anti-socialist crimes subject to severe punishment by the dictatorship of the proletariat.

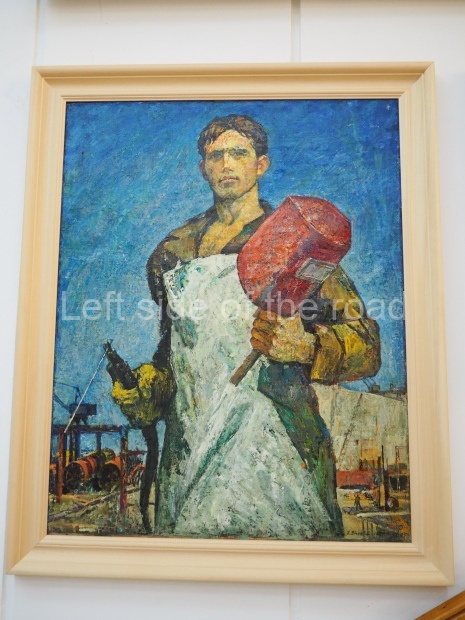

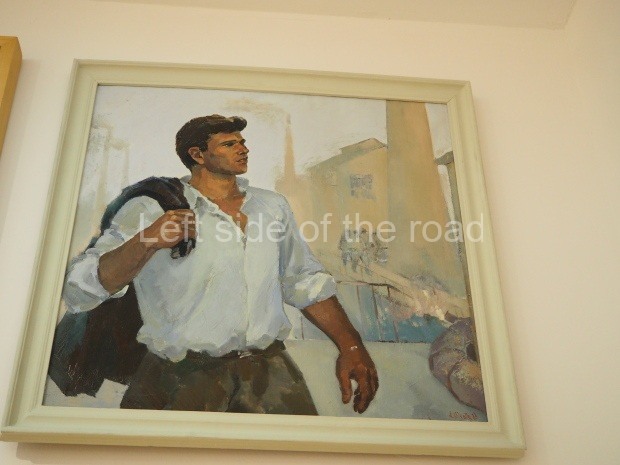

Another very important direction of the ideological work of the Party is the inculcation of the new socialist attitude towards work, so that our people will work as revolutionaries and fight resolutely to put the revolutionary ideals into practice. Only in work and through work is the new man educated and tempered, because work is the greatest school of communist education.

In the atmosphere of great creative work full of selfless revolutionary enthusiasm, which is transforming nature and the consciousness of man, it becomes even more evident how alien and intolerable are the attitudes of those people who dodge work, who are afraid of difficulties and sacrifices, who do not want to disturb their personal ease and comfort, who try to occupy or hang on to some ‘soft spot’, who do their work carelessly and try to grab the maximum from society, who proceed in everything from their own personal interest and material benefit and, with a thousand pretexts and excuses, shirk the duty of working where the people and the country need them. All these are bourgeois attitudes.

The party organizations must carry on a resolute fight against such alien manifestations, incompatible with our communist morality. They must regard the struggle against such manifestations as an aspect of the class struggle, as a struggle against the seed of the bourgeois and revisionist degeneration of people. They must implant the revolutionary socialist concept and attitude towards work among all the working people of town and country, so that everybody regards work as a matter of honour and pride, as a lofty patriotic duty, without which life could not exist. Our people and, first and foremost, the cadres and party members must work with high consciousness and discipline, with military drive and tempo, boldly overcome every obstacle and difficulty, march steadily forward, place the interests of the people, the country and socialism above everything, spare nothing to promote these interests, and be ready even to lay down their lives for these interests. A modest son of our people, son of a family formerly oppressed and exploited by beys and landlords was Hekuran Zenuni, a soldier from the village of Tozhar in the Berat district. He made light of difficulties and sacrifices and went ahead to perform the duty with which he had been charged and, without hesitation, laid down his life in the flower of his youth, just as the 28,000 martyrs did to accomplish their tasks during the National Liberation War. Such are the new men which our Party has educated and tempered.

When we speak about the socialist attitude towards work, the correct understanding of physical work, work in production has first-rate importance. This is a great question of principle to which the organizations of the Party must give special attention in their educational work. The aristocratic concepts about work in production are completely alien to socialism and fraught with dangerous consequences. Any underestimation or deriding of physical work should be condemned as underestimation and deriding of the workers and peasants and the broad masses of the people – a thing that leads to isolation from the people and their work and life, and this isolation is the source of many evils. This should be taken into account especially by those engaged in mental work, the cadres, officials, the technical and artistic intelligentsia, the pupils and students. The overwhelming majority of them have been educated since the liberation of the country and have emerged from the ranks of the working masses, are closely linked with the people and the Party and have displayed and are demonstrating a high level of patriotic and socialist consciousness. Nevertheless, these features should not lead us to underestimate the danger of their becoming infected by bourgeois ideology and, especially, by revisionist views. This is not an imaginary danger, it has a real basis. It is connected with the very nature and conditions of the work and life of people engaged in mental work, and especially the creative, artistic and scientific intelligentsia, who are still very out of touch with physical work and, in many instances, with the working masses and their lives. Among the intelligentsia more favourable ground can be and is found for the spread of individualism and careerism, conceit and haughtiness, unjustified pretensions and an easy life, intellectualism and disdain for the masses.

Our people’s intelligentsia must link itself as closely as possible with the people, must work and live with the workers and peasants and blend themselves inseparably with them. They must reject the bourgeois idea inherited from the past which still has deep roots, that the intellectual knows everything and he alone is able to lead, to guide, to teach and instruct others – an idea which in fact expresses the negation of the role of the masses. It must be clear that the decisive role in all fields of life, including spiritual life, does not belong to particular individuals, no matter how outstanding they are, but to the broad masses of the people. Knowledge does not fall from heaven. All knowledge derives from life and practice and is a product of the struggle of the masses to transform nature and society. Therefore, the men of science, art and culture must listen with attention and deep respect to the opinions of the masses, sum up their experience, always be modest and humble pupils of the great and unmistakable teacher, the people, and make the judgement of the people the fundamental criterion in all their creative work. Some cadres in our scientific institutions are conceited and think that what they say is the last word of science, that any opinion opposed to theirs is worthless; incorrect, and must be rejected, No! Such concepts among the ranks of our scientists must be stigmatized. There is no advance in science or anywhere else without struggle, without clashes of opinions, without class struggle, without debate guided by the Marxist-Leninist principles, by the proletarian ideology, to discover the truth. The idea of the development and progress of science, and not personal glory, must guide each of our scientists in his own work.

The people of the intelligentsia must link their mental work as closely as possible with the physical work of workers and peasants and take part continually, in the proportions laid down, in work directly in production. This duty which has been put into practice widely for all the cadres, intelligentsia, pupils and students, has great theoretical and practical importance. It will help them to become better acquainted with life, to rid themselves of many alien remnants and manifestations and to temper themselves as genuine revolutionaries. This is an important step towards reducing the distinctions between mental and physical work, which, together with the reduction of distinctions between town and country and between the working class and the peasantry, constitutes a major problem which is closely linked with the prospects of our development towards communism. If we do not take measures now to narrow these differences and, willingly or not, allow them to deepen, then our country will not develop towards our final objective and these differences will also become the cause of many evils, of unfair relations between people of mental and physical work, between town and country and between the working class and the peasantry.

Our Party has big tasks to perform also in connection with the inculcation of correct concepts about life so that the moral figure of the communists and all the working people will be the same, not only at work and in society, but also in personal and family life. The cadres, the communists and every worker should live like revolutionaries, lead a modest life of real struggle, they should be the first in sacrifices and the last in pretensions. As the Open Letter reads:

‘… not empty idleness and concern only for oneself, but the ideal of socialism, the struggle to build our socialist Homeland and make it flower with our own hands, the joy of creative work for the good of the people and in their service and the continuous raising of the standard of living of the working masses must be the main objective of their life and struggle, their main preoccupation.’ Principal Documents of the Party of Labour of Albania, Volume 5, p. 38 (Albanian Edition).

The bourgeois and revisionist concept of life, putting money, pleasure, luxury, comfort, personal ease and well being above everything, is alien to our people. The consequences of such a concept have become catastrophic in the countries ruled by the revisionists. Political degeneration, moral corruption, running after money and material gain, selfishness and frenzied individualism, the bourgeois way of life and fashion, and hooliganism are what characterize the life of these countries today, a life which is almost indistinguishable from that of western capitalist countries.

Such alien views on life may and, in fact, do take root in some of our people who are exposed to the strong influence of bourgeois ideology and morality. The party organizations must always be vigilant and carry out a great educational work and struggle to create in the Party, in the collective, in the family and everywhere such an atmosphere as to stifle decadent concepts about the way and purpose of life, sternly condemning all liberal attitudes and laxity in this direction. Through its work the Party must inculcate, especially in the younger generation, our new revolutionary concept of life that is inspired by the lofty ideals of socialism and communism.

All the ideological work of the Party its propaganda and agitation, must be directed first and foremost at ideological and political education, the formation and tempering of people as genuine revolutionaries and communists so that they understand and put into practice the great slogan of the Party: ‘Think, work and live like revolutionaries’ – which constitutes the essence of communist education, the fundamental content of the educational work of the Party.

2 – WE MUST RADICALLY IMPROVE THE METHOD AND STYLE OF THE EDUCATIONAL WORK

Our great objectives in the realm of the cultural and ideological revolution for the education of communists and all the working people in a high revolutionary spirit can not be achieved without further improving the entire content of our educational work and especially the method and style of this work.

It must be said that up to now this work has suffered and is still suffering from dogmatism and stereotypeism, from being out of touch with life, from verbosity, unexplained formulas and a heavy, boring style. Our workers of Marxist social sciences and propaganda have been trying to present our experience in the known terms of theory, reducing it, in the best instances, to examples for illustration, and not enough work has been done to make theoretical generalizations from the Albanian practice, to raise the wealth of factual material that the life of our country during all these years has provided, to the level of science. Therefore, the Party must make every effort to combat this serious shortcoming, and to enliven creative thinking in the field of Marxist social sciences, in our propaganda, and in all our ideological and cultural work.

In addition there are some other weaknesses that have been noticed in the organization and conduct of political and cultural educational activities. In many cases the forms of educational work are standardized and rigid, without spirit or life, little effort is made to adapt them to new conditions and circumstances and frequently nothing is altered until instructions come from above. The fact is that the revolutionary spirit of the Party and masses has far outstripped the propaganda and agitation of the Party. Communists and non-party workers, co-operativists, youth and women are making thousands of innovations and rationalizations which revolutionize their minds and production. However, the same cannot be said about the party workers engaged in propaganda and agitation, or about the workers of the ideological and cultural front, who should advance not alongside, but in the vanguard of all the other working people, to light the way for them, to organize and mobilize them for great deeds. What is the reason for this? Is it that the comrades of the ideological front are incapable, have no ideas and opinions? No. They are some of the best comrades, with a high ideological and political level and tireless workers. The trouble is that they find it difficult to break away from the old stereotyped forms of work and are not closely linked with the work and struggle of the masses.

In the field of ideology and propaganda the Party must struggle also against another serious shortcoming which is seen especially in the daily life of party organizations, as well as of state and economic organs. Here I am referring to the manifestations of empiricism and narrow practicism, the separation of practice from theory, becoming totally immersed in the swirl of daily life, facts and events, the failure to draw general conclusions from the experience of the masses, and the underestimation of theory, which leads to the loss of perspective and deviation from principles. It is regrettable, but a fact, that there are communists in the ranks of the Party who toil day and night but never open a book, that some leading cadres who have neglected their studies, have lagged behind and cannot respond to the great tasks with which life faces them. Some believe that since they have graduated from the University or the Party School they know everything and have nothing more to learn. Others are content with little and think that the study of theory is not necessary for the work they do. All these views must be condemned and sternly combated. The cadres, the communists and all the working people must learn all the time, must learn from life and from school, from practice and theory, from work and from books. This is a never-ending, unlimited job.

The Party has taken and will take measures to improve the work in this field of such importance, combating both dogmatism and empiricism, both lifeless theorizing and narrow practicism. However, these measures will never be sufficient and complete unless the organizations and committees of the Party and the workers on the ideological front use their brains, think and create with initiative, unless they elaborate and enrich the directives of the Party and apply them in a revolutionary way in conformity with the tasks and circumstances. The work of the Party and its ideological work, in particular, is a living and profoundly creative work, which does not tolerate ready-made schemes and stereotypes. The enlivenment of this work is one of the most important tasks of the Party today.

The revolutionizing of all the ideological work, of its content and style, linking it closely with life, must assist, first of all, the more profound and conscious assimilation of Marxism-Leninism by the communists and all the working people of our country. Such an assimilation of Marxist-Leninist ideas and their transformation into a weapon for our working people in their daily struggle is the fundamental distinguishing feature that marks the process of the further deepening of our ideological and cultural revolution. The Marxist-Leninist ideas are the red flag of our Party, its invincible and triumphant banner. They are the foundation of the general line of our Party, they are our guide to action, they light the way for our ideological and cultural revolution, of which they are the basis. Therefore, they must become, and are becoming more and more each day, the property and weapon of the working people.

In this connection we must strengthen and radically improve the study of Marxist-Leninist theory in the Party School, in all categories of our schools and especially in the University and other higher institutes, with the aim that the younger generation and our cadres are formed and tempered as genuine revolutionaries, with broad political and theoretical horizons, closely linked with life and practice. Our schools must give the youth and the cadres profound Marxist-Leninist theoretical knowledge, and give it to them not in a dogmatic way, but creatively, not as an ornament, but as a compass to guide them correctly in life and as a weapon for the revolutionary transformation of the world. The works of the classics of Marxism-Leninism and especially the documents, materials and experience of our Party, which are Marxism-Leninism in action in today’s national and international conditions, must be the basis for the study of our triumphant doctrine. At the same time, we must intensify and improve the propagation of Marxist-Leninist ideas through the press and publications, by printing and publishing more articles, books and pamphlets, works of the classics of Marxism-Leninism, not only complete works but also selections on specific themes, dealing with particular problems on which the cadres and workers need direct help.

Our struggle for the assimilation of Marxist-Leninist ideas, for the deepening of the ideological and cultural revolution, cannot be waged successfully unless the whole Party, the communists and all working masses are drawn into it, unless the line of the masses, the line of thorough socialist democratization, is implemented boldly and in a revolutionary way here, as everywhere else. To put such a line into practice, a stern struggle must be waged against the reactionary bourgeois intellectualist concept that theory, philosophy, science and art are too difficult to be grasped by the masses, that they can be understood only by the cadres and intelligentsia, because the masses have not reached the level necessary to understand them! This means to make theory and science a bugbear for the masses. This means to make Marxism-Leninism a bugbear for the masses, too, because Marxism-Leninism is a theory and science. We must declare relentless war on this concept. Marxism-Leninism is not a monopoly of a privileged few who ‘have the brains to understand it’. It is the scientific ideology of the working class and the working masses, and only when its ideas are grasped by the broad working masses does it cease to be something abstract and is turned into a great material force for the revolutionary transformation of the world. The historic task of our Party is to continually deepen the ideological and cultural revolution and carry it through to the end by relying on the masses of workers, peasants, soldiers, cadres and the intelligentsia and drawing them actively into creative revolutionary activity.

Enver Hoxha, Selected Works, Volume 4, pp 163-180

More on Albania …..

View of the world

Ukraine – what you’re not told