More on Moldova – on the Post-Socialist Countries – Eastern Europe and Asia page

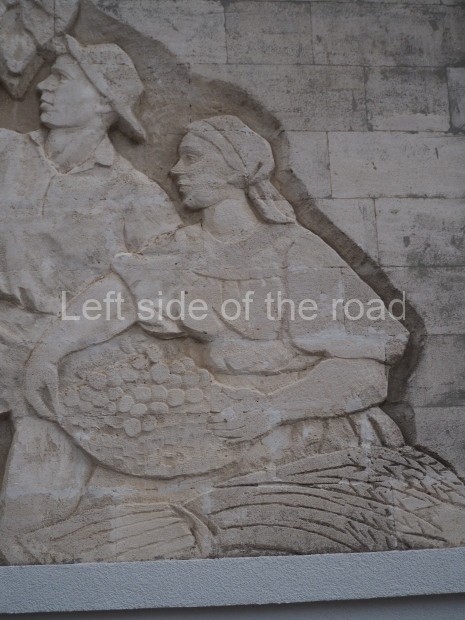

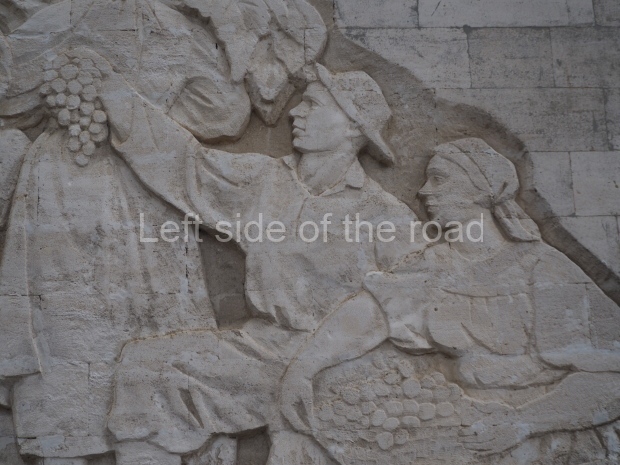

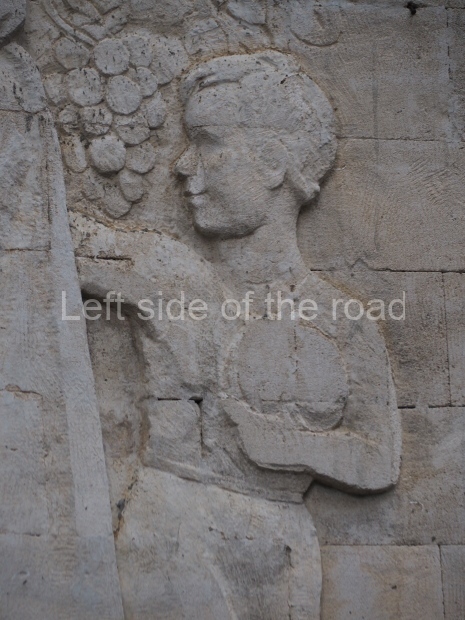

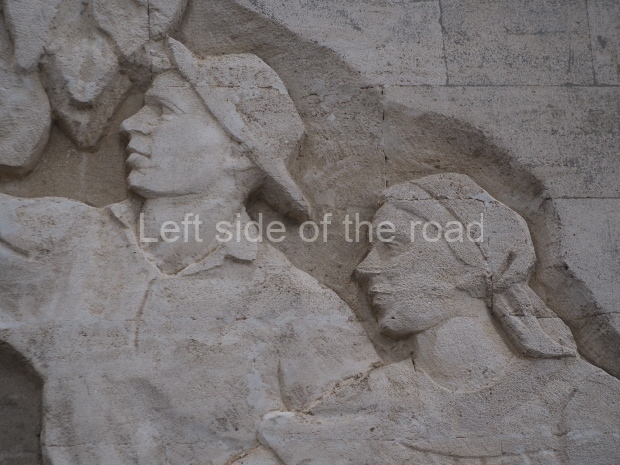

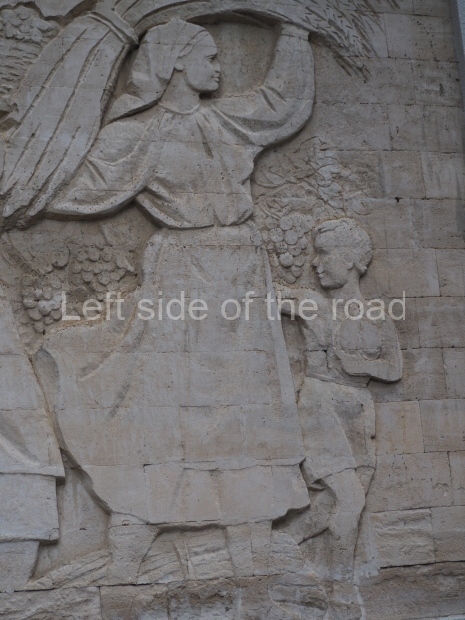

Agricultural bas reliefs – Valea Morilor Park – Chișinău – Moldova

There’s a limited amount of Soviet decoration still visible in Moldova and only one example of this art work in the form of bas reliefs (so far) in Chișinău, the capital of the country.

This is on the façade of a building which is now some banal events venue but which must have had a more official function in the Soviet past.

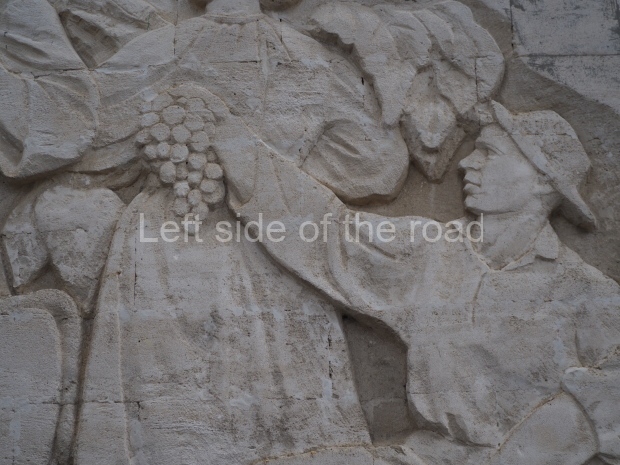

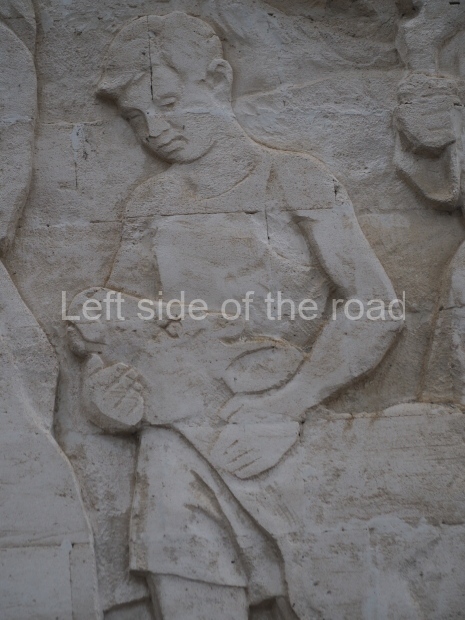

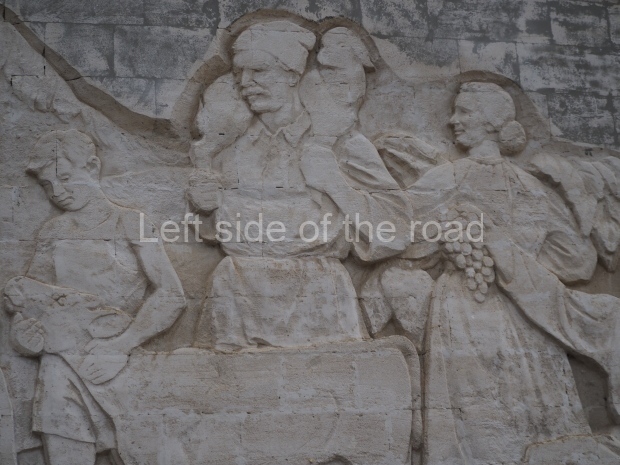

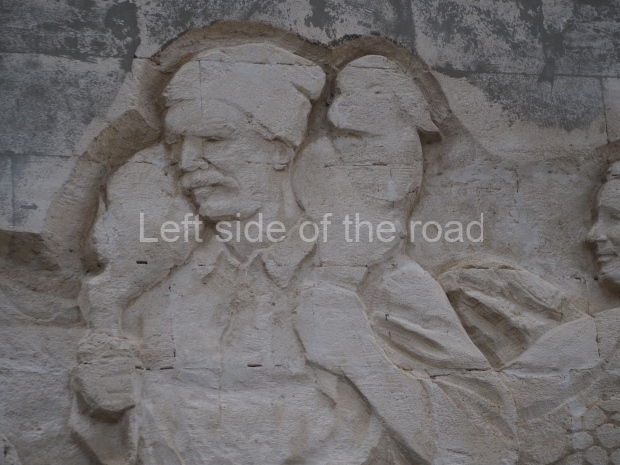

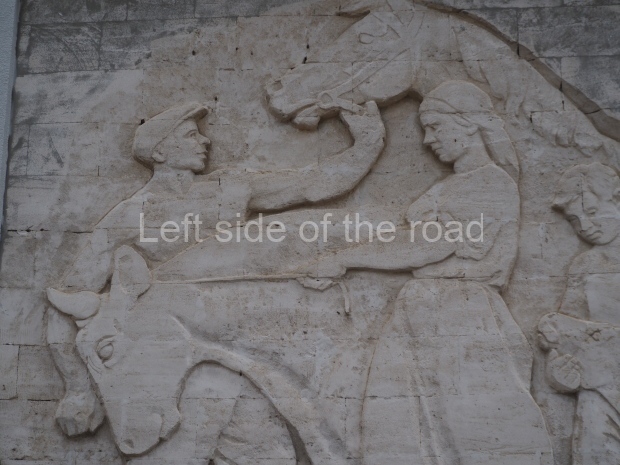

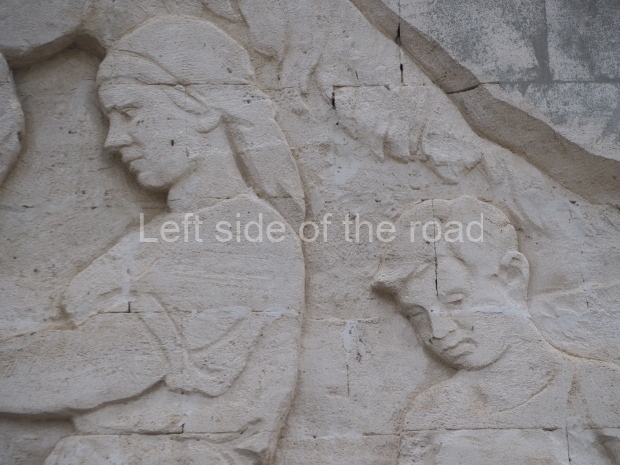

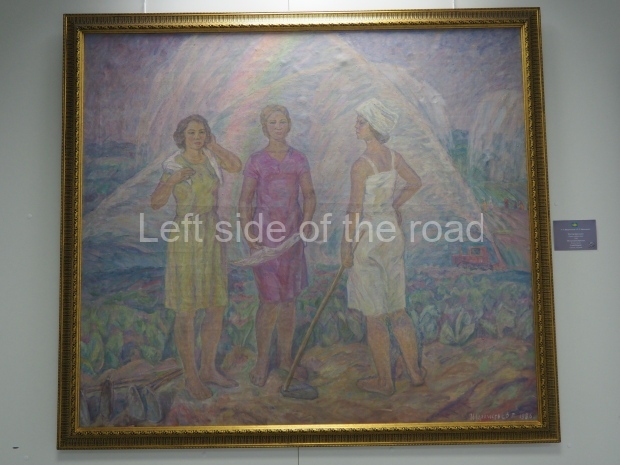

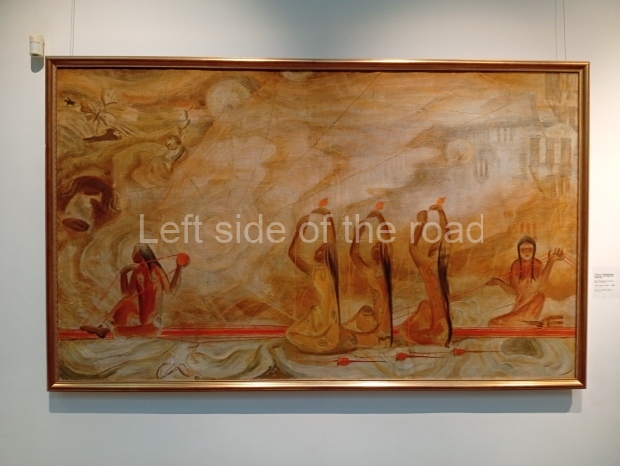

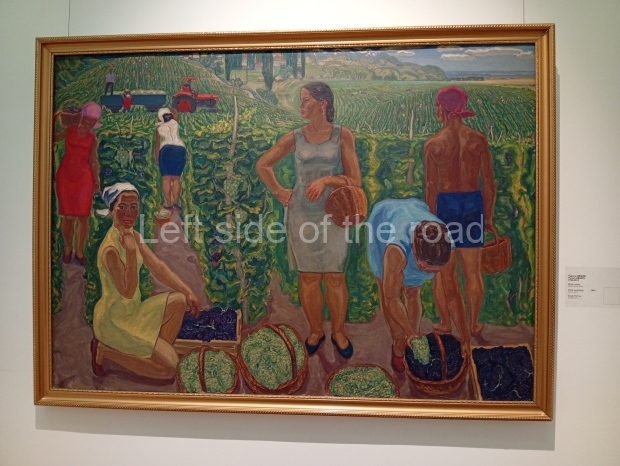

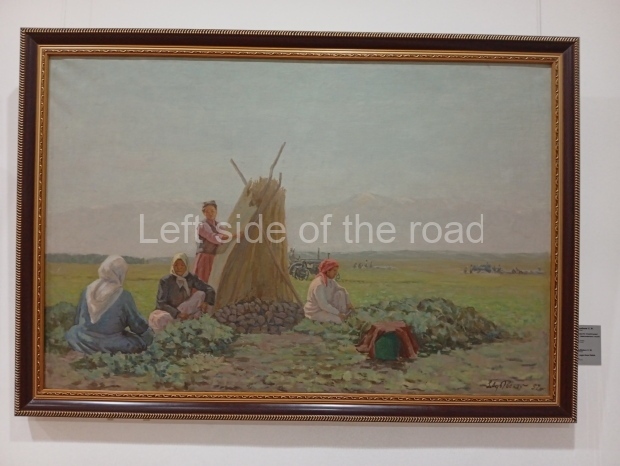

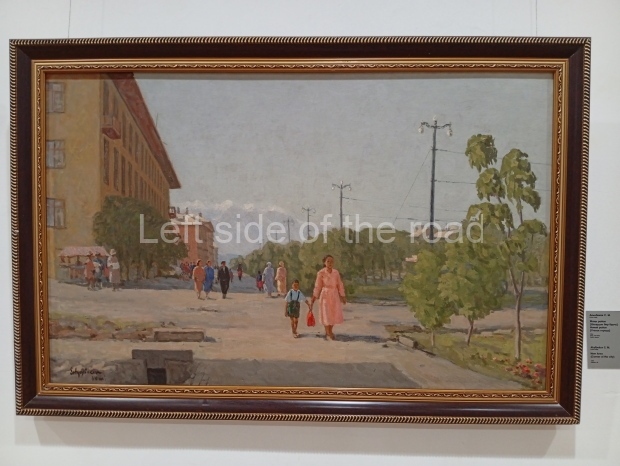

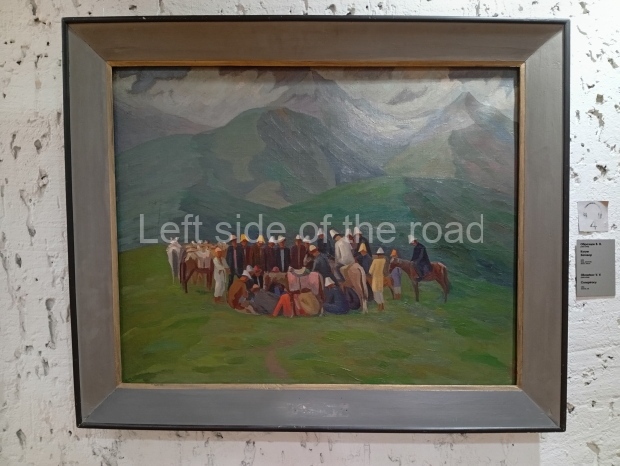

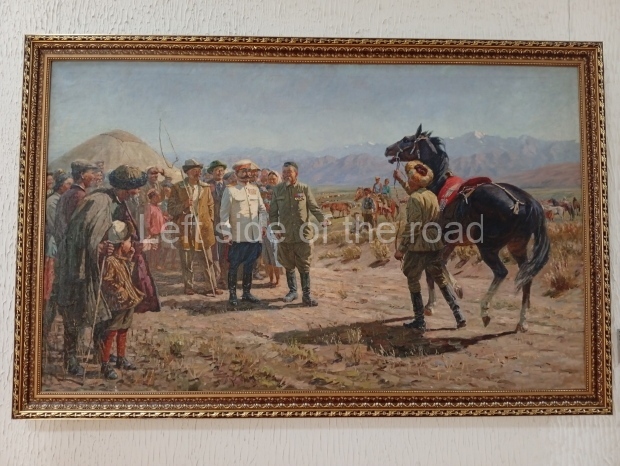

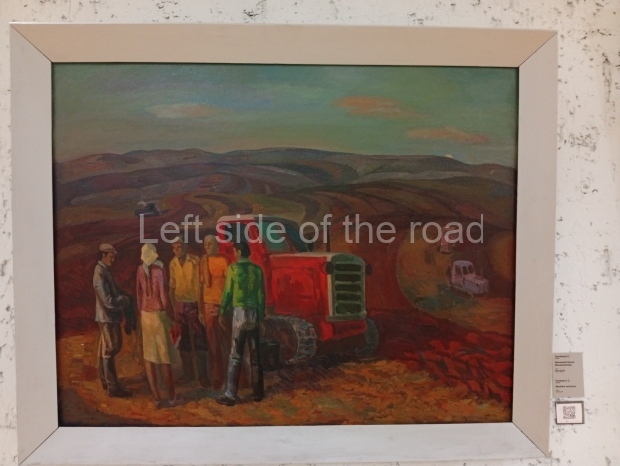

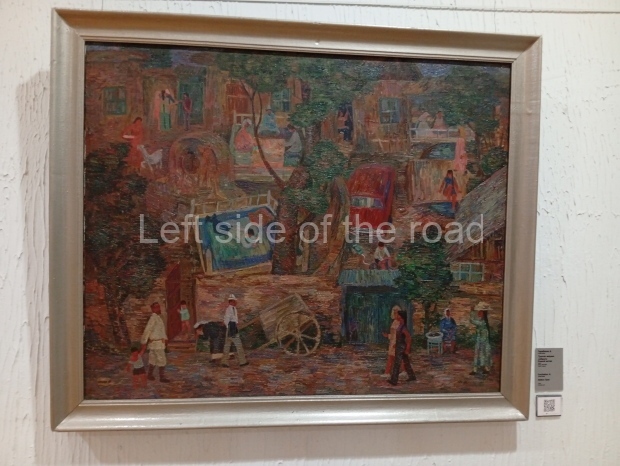

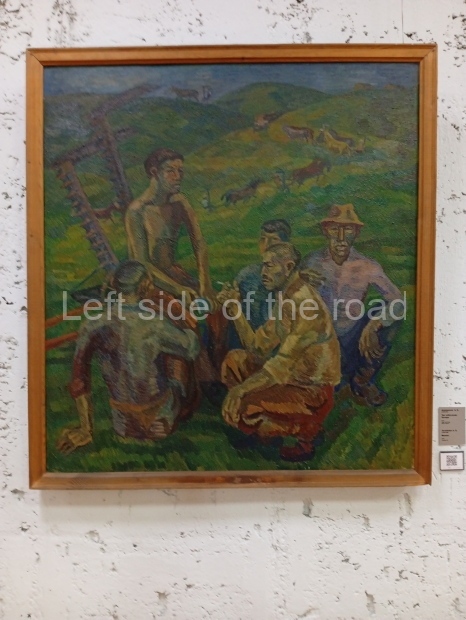

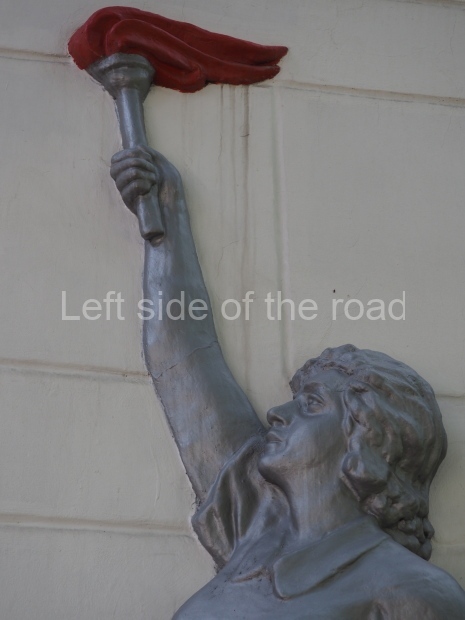

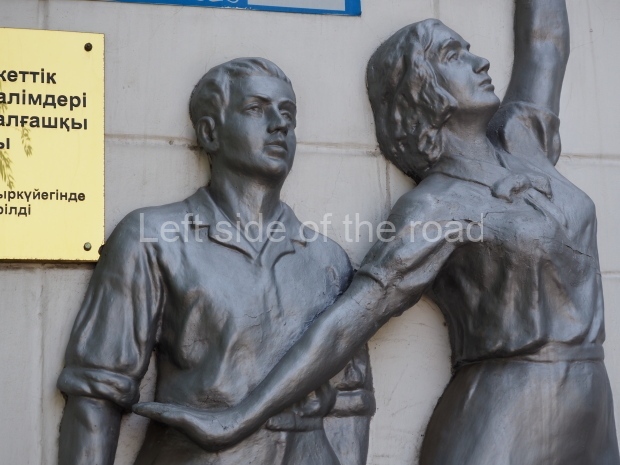

What we have here are two tableau depicting agricultural, collective farm, life during the period of the construction of Socialism in the Soviet Union.

These are very reminiscent of the images that can be seen on the external walls of the Republic pavilions at the Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy (VDNKh) in Moscow, but I didn’t – at the time of my visit – note exactly what images were representing which Republic.

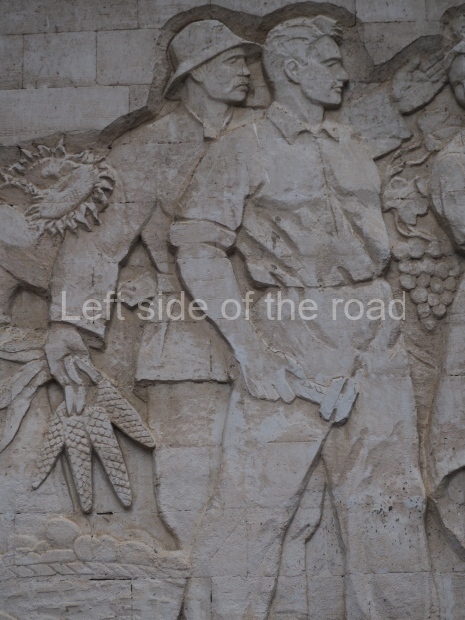

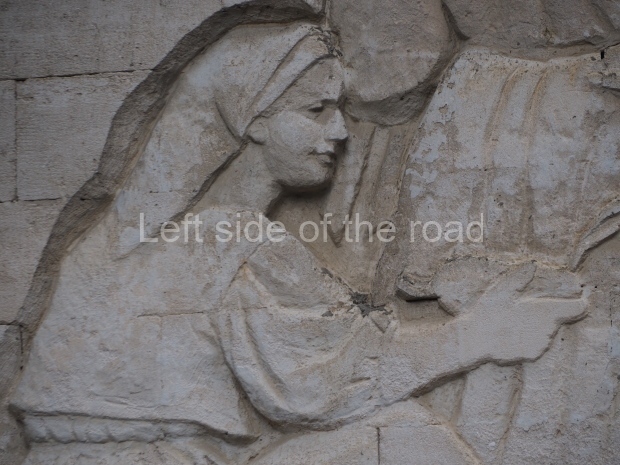

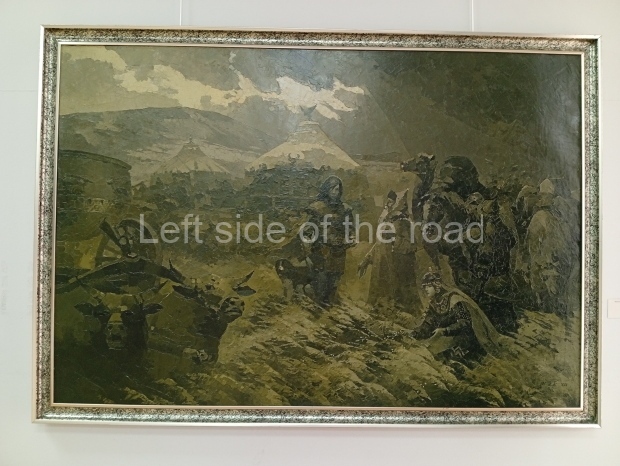

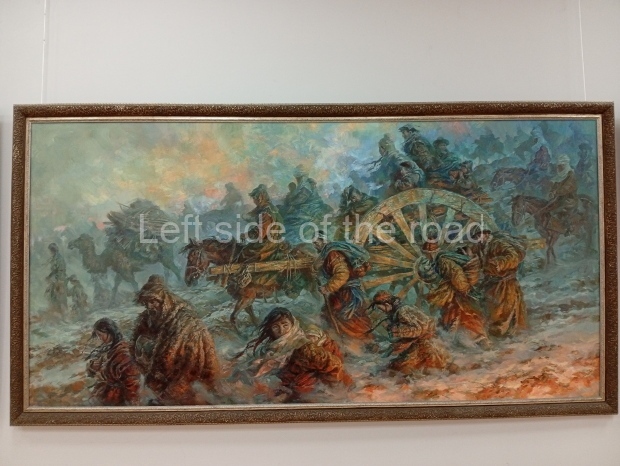

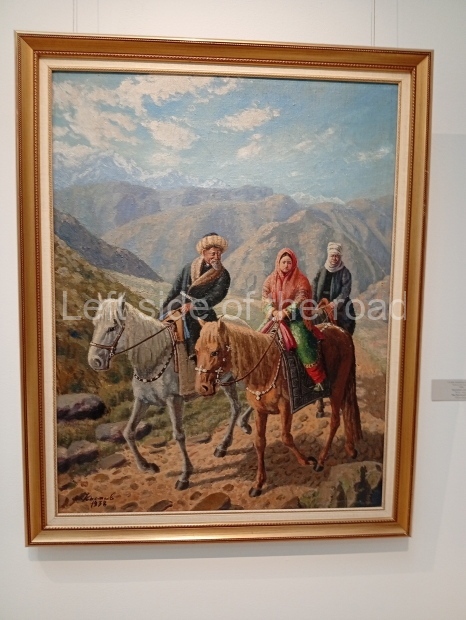

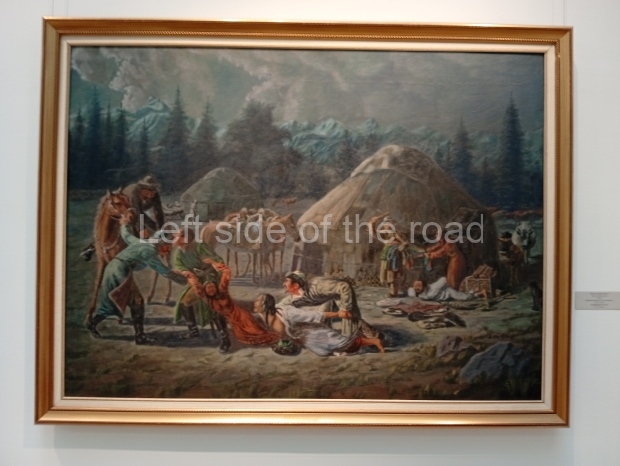

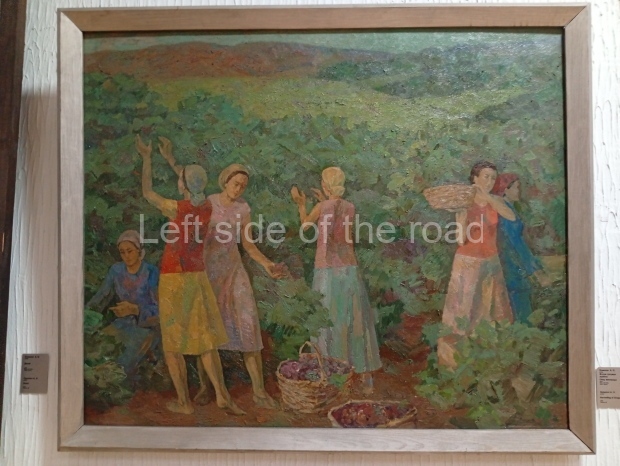

What we have in all such bas reliefs is a respectful representation of working people, productive and working not just for themselves but for the benefit of the collective. We have men, women and children all involved in the productive process from which all will receive the awards and not having the fruits of their labour stolen by the capitalist owners of the means of production. There was a time when the workers of the USSR (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) had the reins of power in their hands. The fact that they allowed those reins get into the hands of the exploiting class following the death of Comrade Stalin (in 1953) is, for the sake of this discussion, irrelevant. For a time they had the power – why they allowed that power to be taken away from them is an important matter but not something which can be covered here. (That ‘debate’ is available on other pages of this blog.)

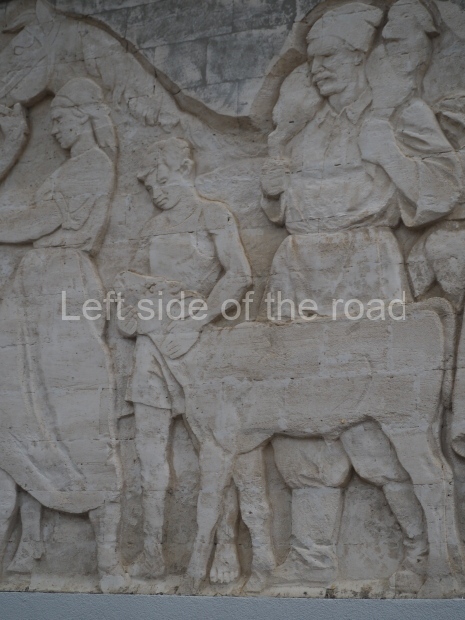

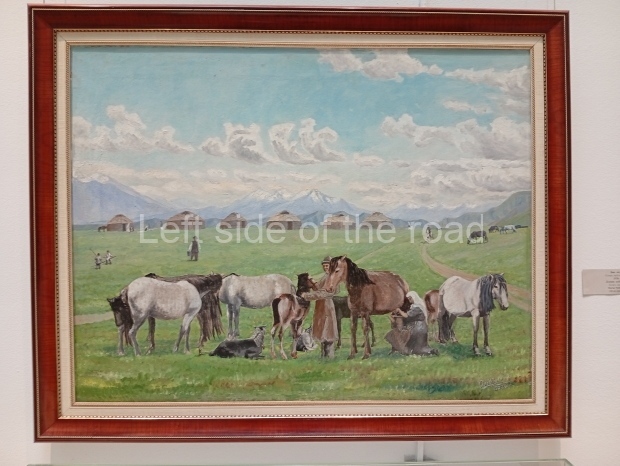

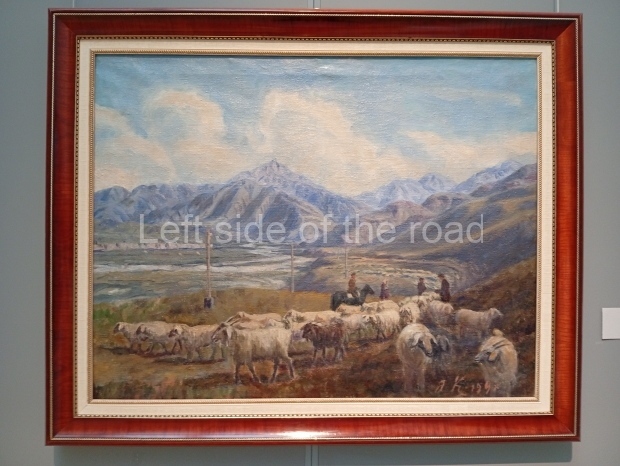

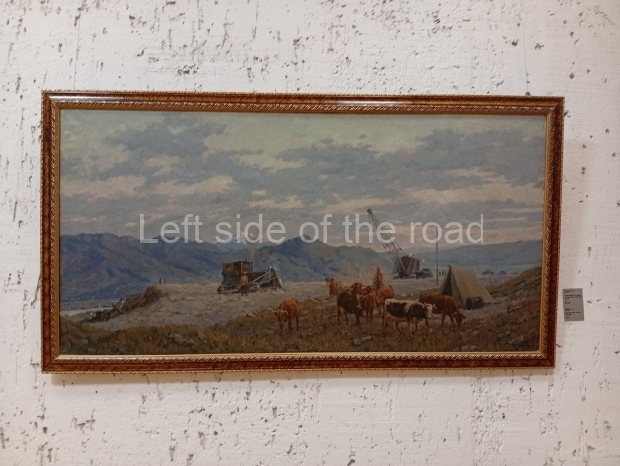

In these images there’s always a gentle relationship between the collective farmers and the animals they tend. This would always be an idyllic representation. Farm life, when it comes to livestock, is invariably cruel. The animals are there for one reason – that it to be exploited for what they can produce whilst alive and to provide protein on their deaths. But even though that would have been the reality on any Soviet State/collective farm it would have lacked the industrial slaughter that exists under capitalist food, factory production process. I don’t want to romanticise Soviet agriculture but I don’t believe it ever reached the level that was already a long established norm in the ‘killing fields’ of the like of the Chicago stock yards as was depicted in Upton Sinclair’s ‘The Jungle’. In that capitalist environment it was (and is?) difficult to work out who was the more abused, the animals or the human workers.

Whether that situation would have arisen even if revisionism and the restoration of capitalism had not occurred in the Soviet Union is a moot point. Whatever the future might have been the past of a gentile relationship between man and animal is still preserved in the bas reliefs on the building close by the Valea Morilor Lake in Chișinău.

These images also tell the history of the country, in that those agricultural products that were important in the country in the 1960s/70s (when I assume the bas reliefs were produced) are there on the wall – the grapes (for the wine), the sunflowers (for the oil), the maize (for the cobs) and wheat (for the flour).

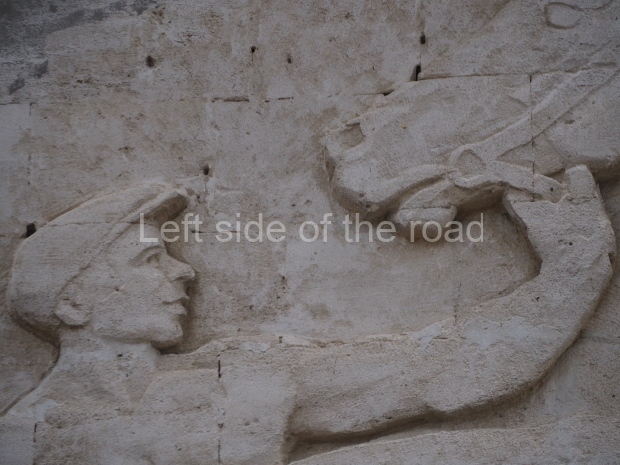

Somewhat surprising (to me) is the lack of a significant reference to industry. The unique representation is in a male with spanner. No mechanisation, no tractor/combine harvester in the imagery, no indication that agricultural production was moving away from a situation of ‘idiocy of rural life’. This is not meant as a criticism of the skills of agricultural workers but of the fact that their working life had traditionally led them to an existence of isolation and a lack of organisation which was forced upon industrial workers with the development of factories and the concentration of hundreds (and thousands) of workers in a restricted area. They wouldn’t have chosen that move if given free will – they would have preferred working in a ‘cottage industry’ with their cow, pig and chickens on common land and a small vegetable patch – but that was stolen from working people by the first major privatisation of the modern age with the Enclosure Acts (where the rich stole from the poor in a blatant act of ‘legalised’ theft).

So these public works of art told a part of the history of the common people in Socialist societies. When they were/are obliterated in a purge of the past because capitalism doesn’t want the working class to even remember what the construction of Socialism (with the potential to lead to Communism) had meant to their lives then they will just accept the ‘norm’ that capitalism offers – to stay in your place, to accept what is given and allow the billionaires to rake in unbelievable amounts of wealth whilst the poor get poorer and as their ranks are increased.

That is why the images of Socialist Realism are being destroyed and, in an attempt to combat that revision of history, why that imagery that remains is being documented on the pages of this blog.

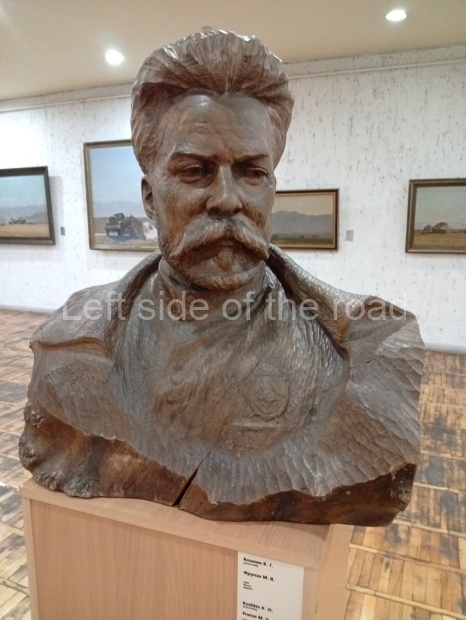

If you head to the lakeside to see these bas reliefs then you cannot but avoid also visiting the tableau of the three outstanding Communists – Karl Marx, VI Lenin and Georgi Dimitrov.

Location;

Strada Ghioceilor 1, Chișinău,

By the Moldexpo International Exhibitions Centre and at the edge of the Valea Morilor Lake.

GPS;

47.01631 N

28.80432 E

More on Moldova – on the Post-Socialist Countries – Eastern Europe and Asia page