Hungarian Railway History Park, Budapest

To the north west of the city centre, situated in what used to be the principal maintenance and repair workshop for the Hungarian National Railways in Budapest, is a railway ‘theme park’ giving visitors a glimpse of the development of the railway system in the country.

Obviously a mecca for train enthusiasts it also is a place for anyone with an interest in industrial history in general. There are many examples of early East European steam engines as well as redundant passenger, goods and maintenance units. In many ways it also appears to be a bit of a dumping ground for one of every working vehicle from the relatively recent past of the Hungarian railway system. That means that some of the exhibits are in a sorry state of disrepair and whether they will ever be returned to their former glory is debatable (or really very unlikely) considering how long it takes, and how much it costs, to get these massive pieces of machinery back to their original condition.

Some of the things that stood out to me;

- the two locomotive turntables, both of which, I think, are still in working order and one of which, the one furthest from the entrance, is regularly used to turn engines around as part of the entertainment of visitors;

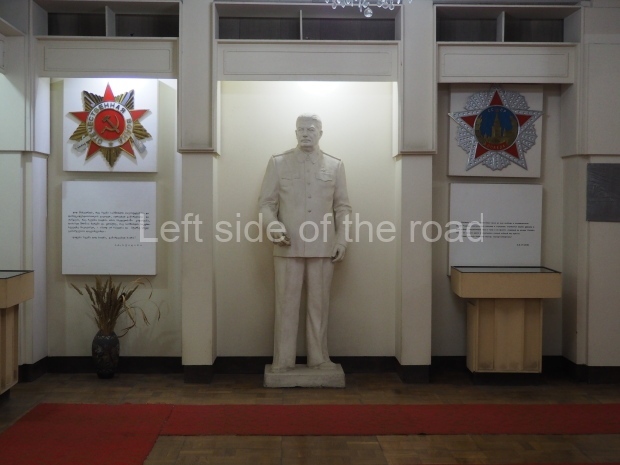

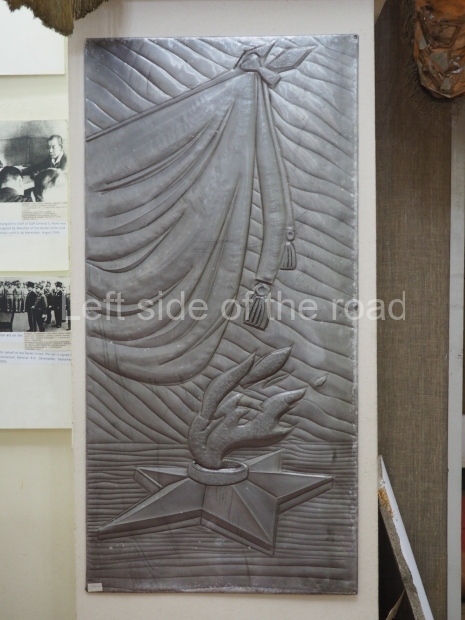

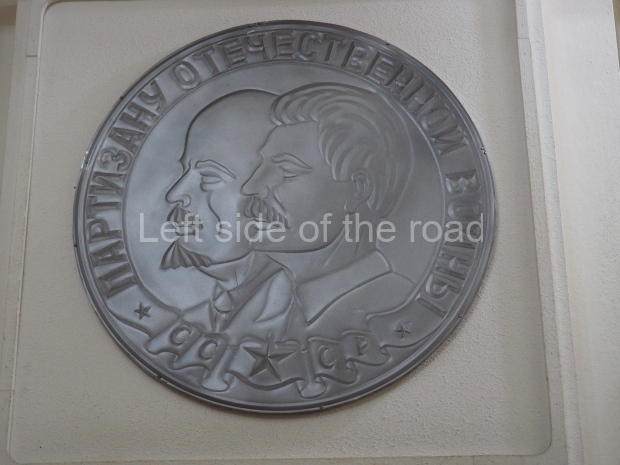

- a couple of statues of railway workers, near the entrance, which during Hungary’s Socialist period would have been display in a more communal space and not relegated to a museum;

- the distinctive shape of the steam engine funnels;

- and the way that some of the components were outside the frame of the engine;

- an old snowplough, which was attached to a the front of a steam locomotive, with a huge bladed fan which would throw the snow to the sides of the tracks, all encased in a wooden frame. It would have been a wonder to have worked in it – but also, I would think, a bit like working in Hell;

- getting up and close to the only regularly working steam engine which, I thought, strangely was one made for the US Army in the 1940’s, incongruously, sports a large Red Star on the front of the boiler. You don’t normally get that close to these spitting and sometimes angry wonders, the result of the first industrial revolution;

- the smells of the cinders in the air when the steam engine is in motion, for those old enough to remember, a smell that indicated you were getting close to the museum;

- the ability to get a relatively close view of the maintenance and refurbishment workshops, the smells and all that it entails to get locomotives up and running again;

- the distinctive style of mid to late 20th century local passenger trains of Eastern Europe (all such modern units are homogenised);

- as in all transport museums the class difference displayed in the comfort of the passengers in the various short and long distance carriages.

I went there on a Saturday, which meant crowds of children, but at the same time there was probably much more going on due to the fact there were many people in the park. For example, I don’t think the demonstration of the workings of the turntable would have been so extensive on a quieter day in the week.

Apart from the demonstration of the turntable it is also possible, for an extra payment, to ride on the footplate, and at the ‘controls’, of a steam or diesel engine, something that would be totally unacceptable in anal fixated Britain.

One slight drawback for a non-Hungarian was the fact that there was little information about the exhibits in English.

It is hoped the slide show below will provide a taste of what’s on offer.

Location;

Tatai út 95, Budapest

GPS;

47.54243064388407º N

19.095641067204674º E

How to get there by public transport;

From outside the Keleti palyaudvar (railway station) take the blue bus number 30 or 30A and get off at the Rokolya Ucta bus stop – indicated on the scree, and announced over the speaker, in the bus. Walk in the direction the bus was going and at the first junction turn right. Two blocks down come to a T-junction and the entrance to the park is across the road in front of you.

Opening times;

Tuesday to Sunday 10.00-18.00. Closed Monday.

Entrance;

Adult; 2,700 HUR (advertised price but I was charged 3,000 HUR for some unknown reason)

Various pricing arrangements for children and families.