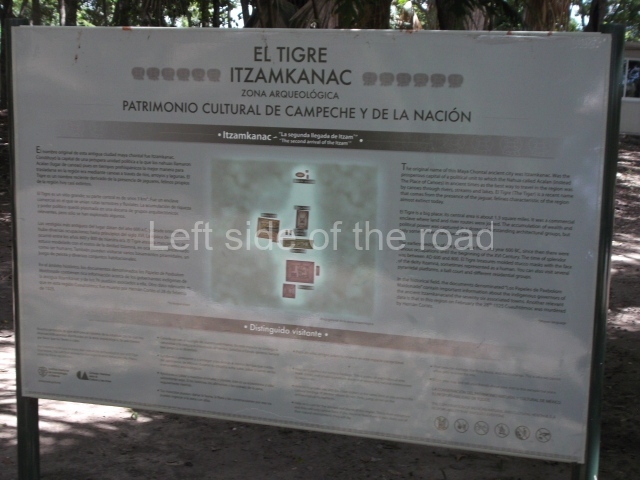

El Tigre – Itzamkanac

More on the Maya

El Tigre – Itzamkanac

Location

This is a fairly large province encompassing the River Candelaria and part of the Terminos Lagoon and Sabancuy Estuary. To reach the capital El Tigre (Itzamkanac) from Ciudad del Carmen or Champoton, go to Escarcega, take the turn-off to Candelaria but before you reach it follow the sign to El Tigre, on the banks of the Candelaria. This river is formed by two large tributaries, the Caribe and the San Pedro: the former rises in the Calakmul lowlands and the latter near Flores in Guatemala. It is associated with the two great Maya capitals – Tikal and Calakmul. As it flows past El Tigre, the river is 150 m wide and is navigable throughout its course, although a few kilometres beyond the village of Candelaria numerous waterfalls complicate navigation but enhance the beauty of the landscape.

History of the explorations

Itzamkanac was first visited by Hernan Cortes in 1525 and subsequently received visits from Alonso Davila, the first encomenderos (Spanish settlers to whom the Spanish crown granted control over a certain number of indigenous people) and various monks. In 1557 the population was obliged to abandon the place and move to Tixchel. In relation to more recent explorations, the earliest of these was conducted by W. Andrews IV (1943), who sailed up the River Candelaria and recorded El Tigre and other sites. We then have the extraordinary work carried out by Scholes y Roys (1948), who described the region and identified Itzamakanac in the ruins at El Tigre and Tixchel on the coast. Pina Chan and Pavon Abreu visited El Tigre in 1959, publishing photographs and a brief description in an article in which they conclude that the site is the Itzamkanac of the historical sources. It was thanks to the interest shown by Pina Chan that a project affecting various structures was conducted in 1984. Prior to that, Lorenzo Ochoa had toured the Candelaria basin with Ernesto Vargas P. and Sofia Pince, and they subsequently made separate tours to shed a little more light on the whole province. Since 1996 Ernesto Vargas P. has been conducting tours of the whole Acalan-Tixchel province based on several of the approaches laid down by Pina Chan, and he has also worked on various structures at the site in collaboration with the State Government, Petroleos Mexicanos and the INAH and UNAM. The site is open to the public, who can view the masks, a ball court and several of the structures.

Pre-Hispanic history

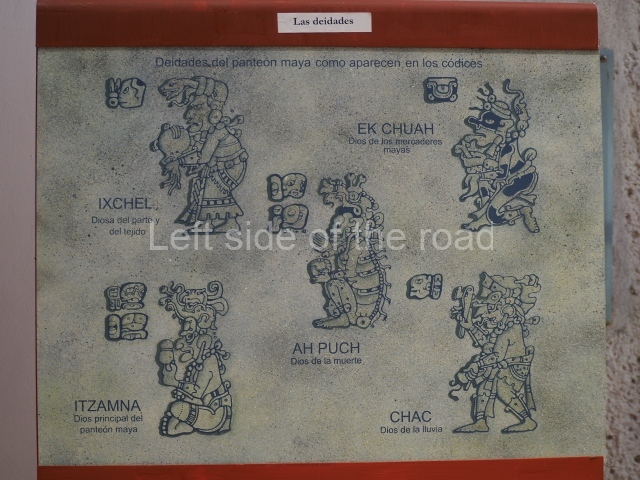

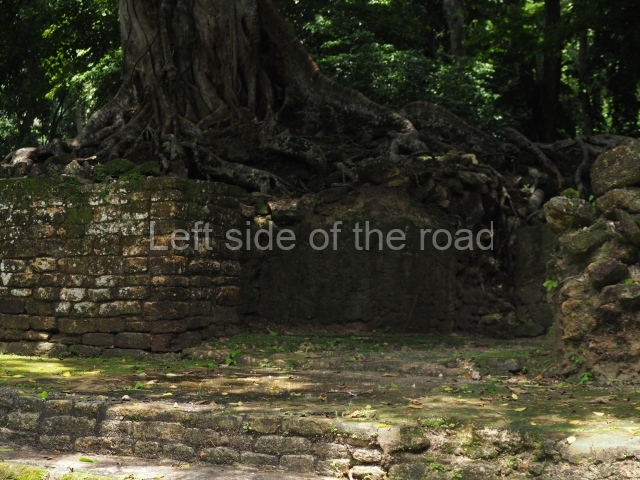

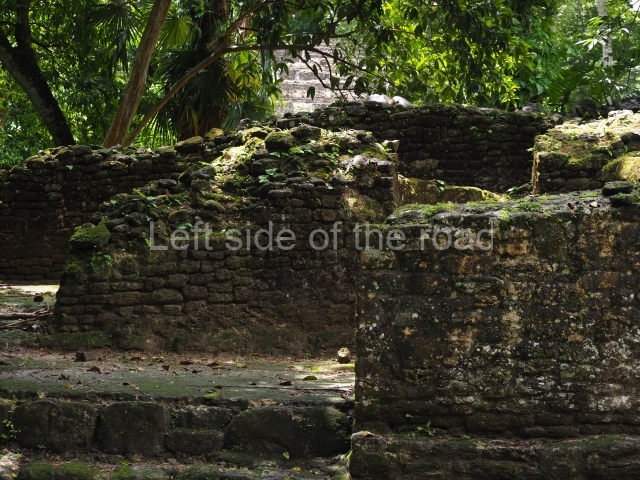

According to historical sources, the Acalan province stretched from Tixchel by the sea, along part of the Terminos Lagoon and the entire Candelaria river basin, to Tenosique. Various researchers have identified Itzamkanac, its capital or administrative centre, with the archaeological site of El Tigre-Campeche. Hernan Cortes passed through the place en route to Las Hibueras in 1525; later on, Alonso Davila re-established the town of Salamanca de Itzamkanac, although it was rapidly abandoned. Neither of them reached the place by the known routes, but we do know that various fluvial and terrestrial routes passed through the Acalan province. The principal one was the River Candelaria, which permitted trade with distant places such as Tixchel, Xicalango, Potonchan and even Nito and Naco in Honduras. A tour of the basins of the rivers Candelaria, Caribe and San Pedro revealed over 150 archaeological sites, proof that the area enjoyed great importance during the pre-Hispanic period. The largest sites are El Tigre, Cerro de los Muertos and Santa Clara on the banks of the River Caribe. Situated on the hills overlooking the River Candelaria, El Tigre was clearly a strategic enclave. The settlement is dominated by a main precinct with structures that stand over 20 m tall, the residential area and a road. Its occupation dates from the Late Preclassic, as demonstrated by several of the masks that have been analysed at Structures 1 and 2. However, the site experienced its heyday during the Terminal Classic and survived until the Late Postclassic, as shown by the finds uncovered at the top of these same buildings.

Site description

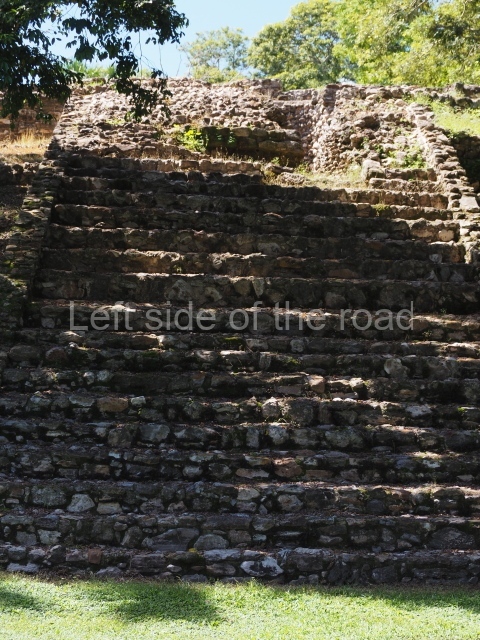

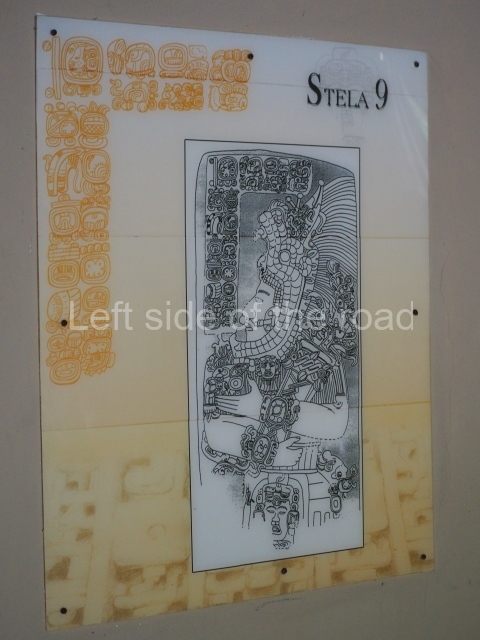

The Ceremonial Precinct is composed of 4 large structures, 6 smaller structures, 2 plazas, 13 altars, 3 stelae and the access roads to the site. The most work has been conducted on Structures 1, 2 and 4. Structure 1 is bounded to the south by the great plaza and measures approximately 150 m along the north-south axis and 135 m along the east-west axis. It is approximately 8 metres high and is surmounted by four platforms, two of which face the front; a 23m-high pyramid rises at the rear of the structure; access to the top of it is via stairways which have been consolidated and reveal the three principal constructions phases of the building: Late Preclassic, Terminal Classic and Postclassic.

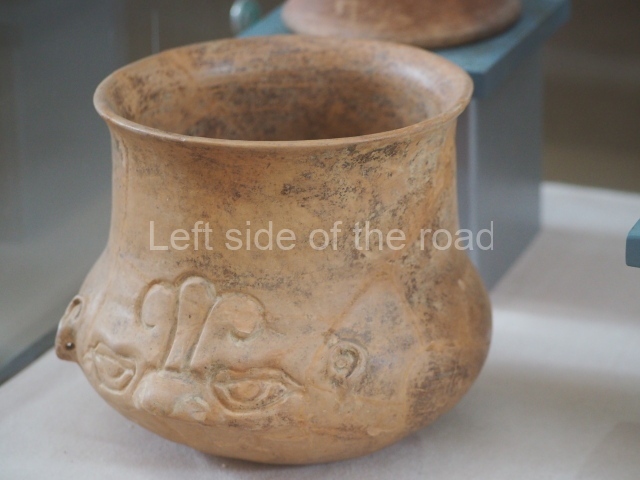

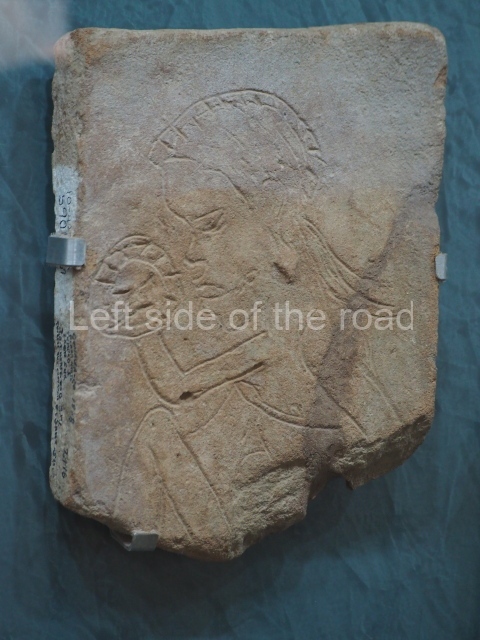

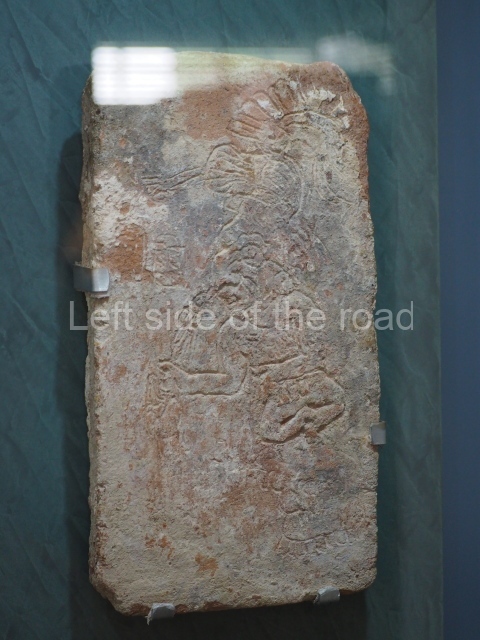

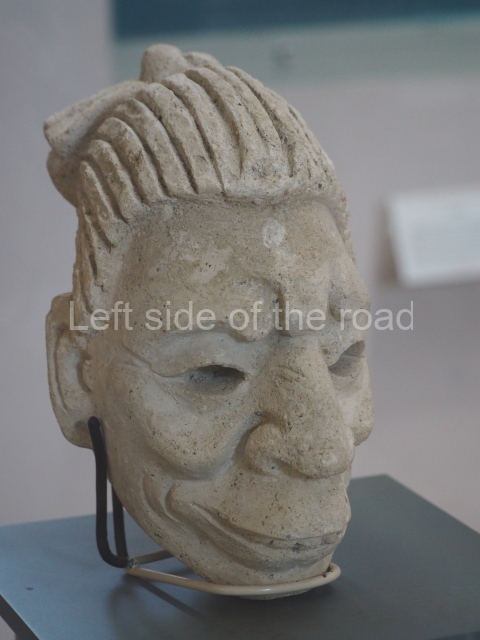

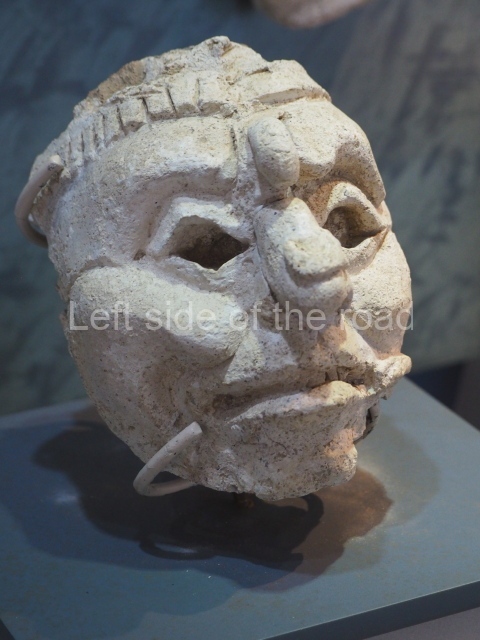

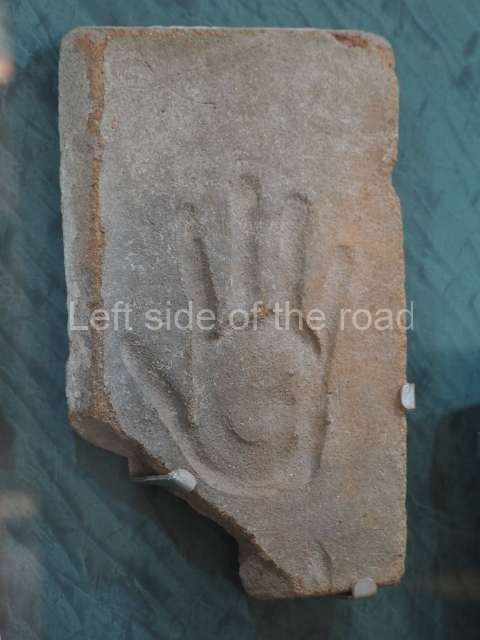

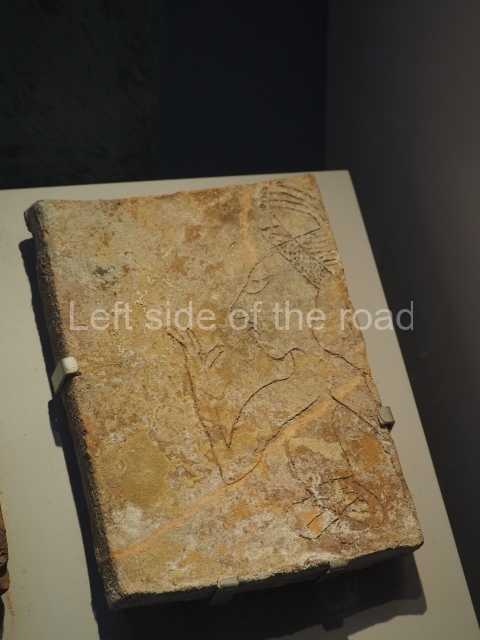

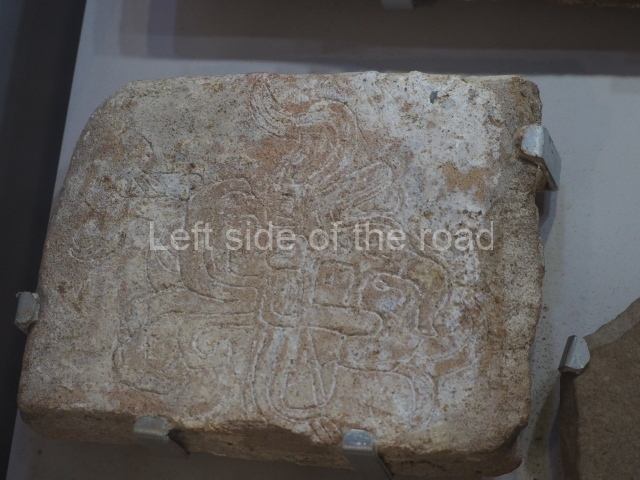

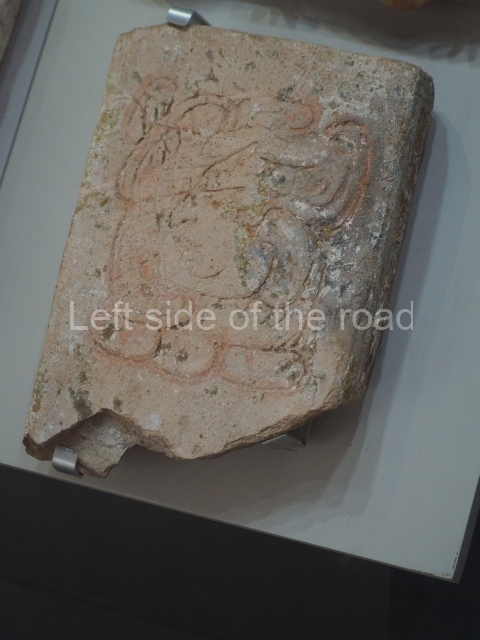

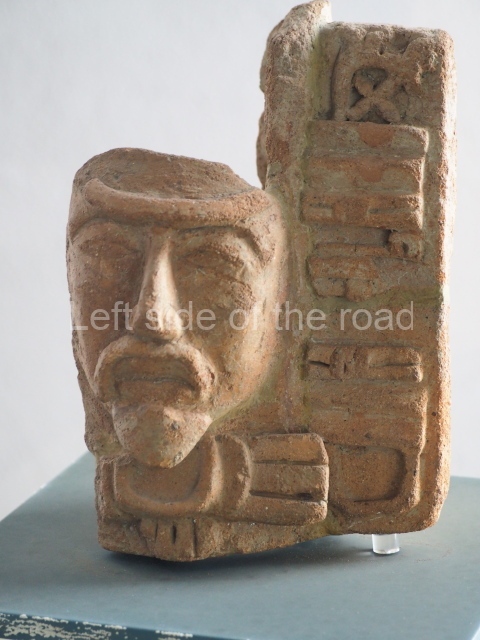

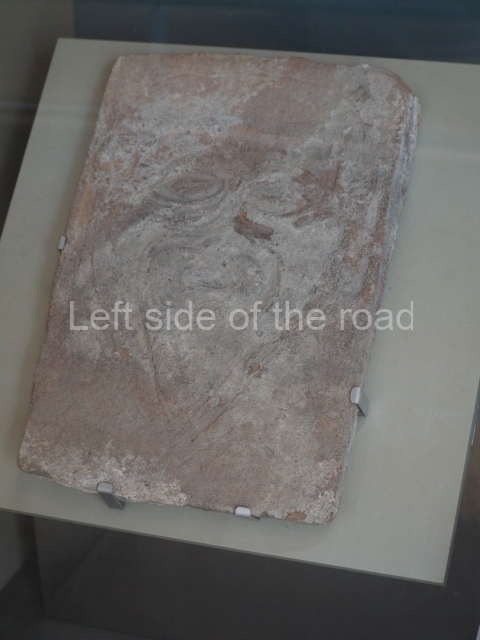

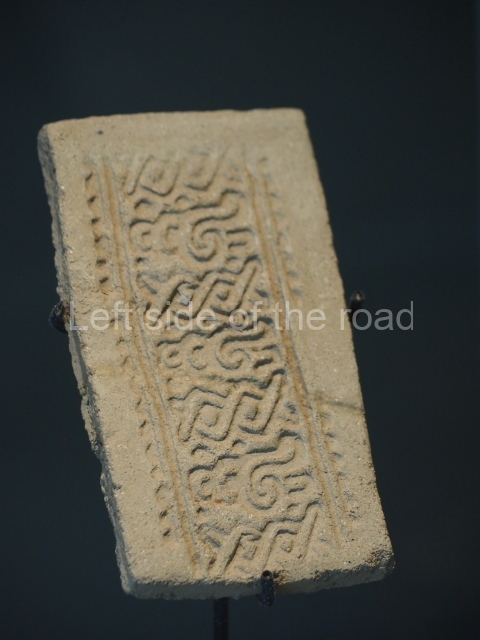

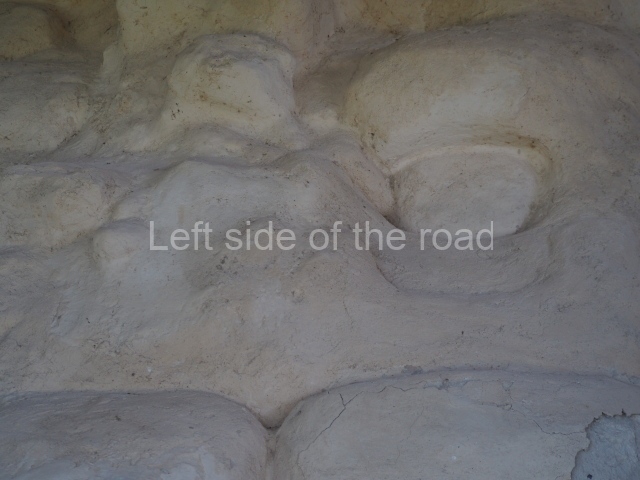

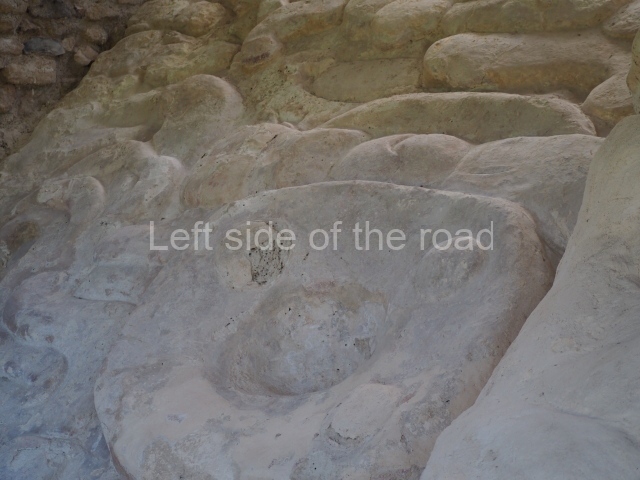

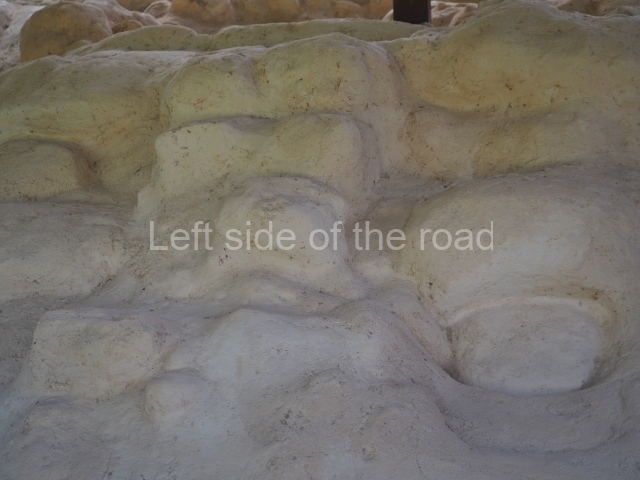

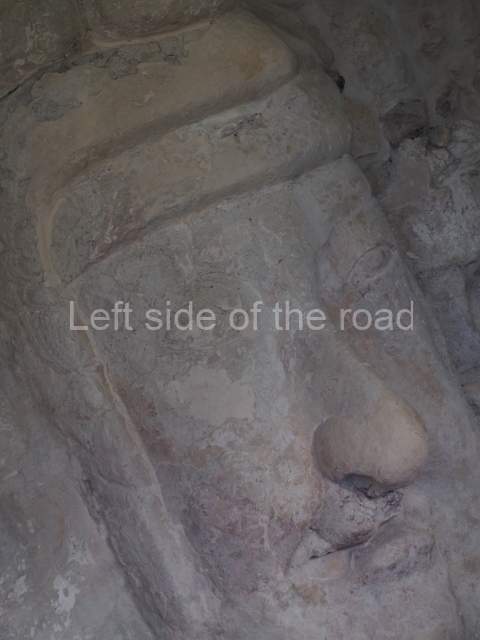

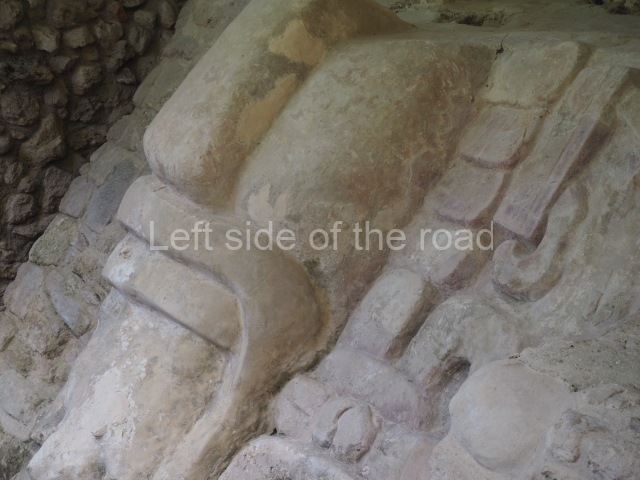

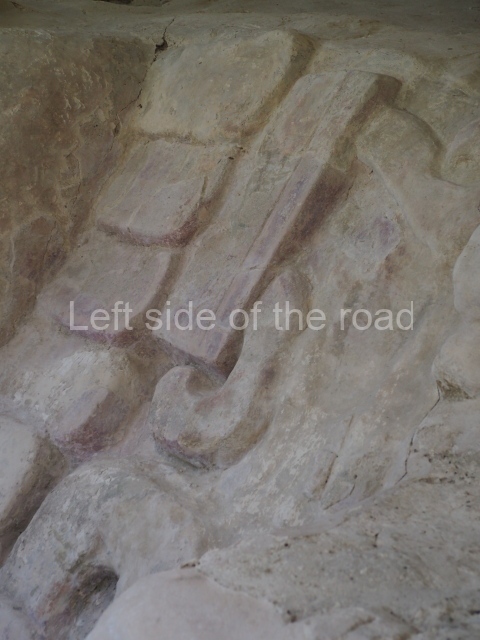

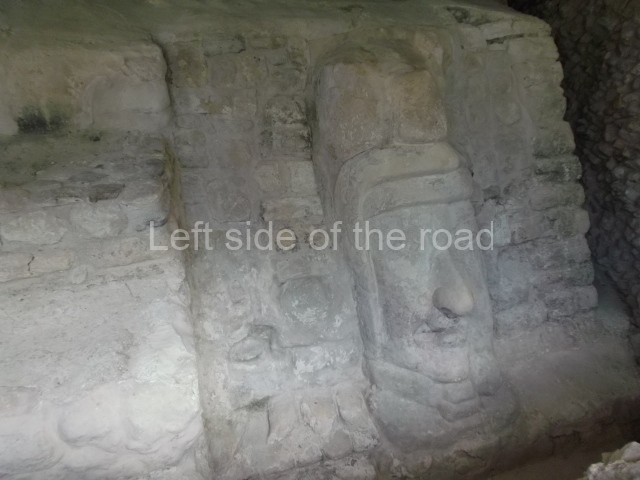

Masks 1 and 2 are located on Platform 1c Sub and belong to a substructure which, judging from the ceramics found and other characteristics, corresponds to the Late Preclassic. Various anthropomorphic and zoomorphic masks have been identified; the former are human faces with a clearly discernible chins, mouths, noses, eyes, plumes and ear ornaments. All of them are painted in red and cream and show traces of black paint. Mask 1 is well preserved and must represent an important figure as it is painted red, the colour identified with power. The head and the sides of the face were covered by a type of helmet – partly destroyed – with three bands and what appears to be an ornament at the centre. Ear ornaments flank the face. These are very simply decorated, showing a large circle with bows or knots and decorative hooks. The entire mask rests on a talud or sloping wall and is divided by a stairway with three steps but no balustrades; intertwining knots or bows can be discerned both above and below the ear ornaments. Below these, what appear to be three leaves reach down to the level that supports the platform and create the impression of being extensions of the ear ornaments. Another design can be discerned above the knot. The symbols presented are associated with royalty, which in subsequent times would appear in Maya iconography and sources.

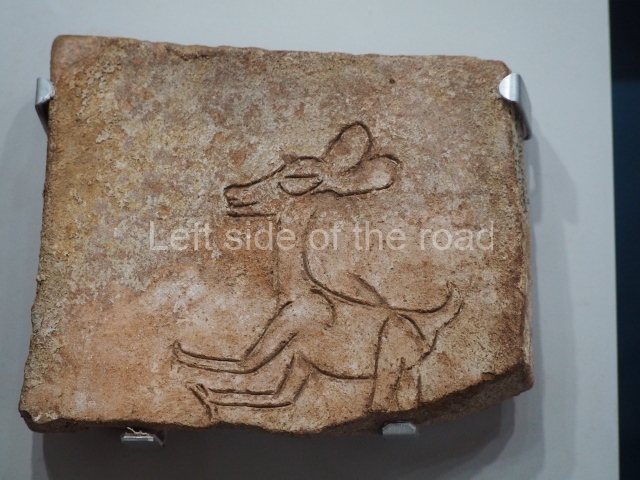

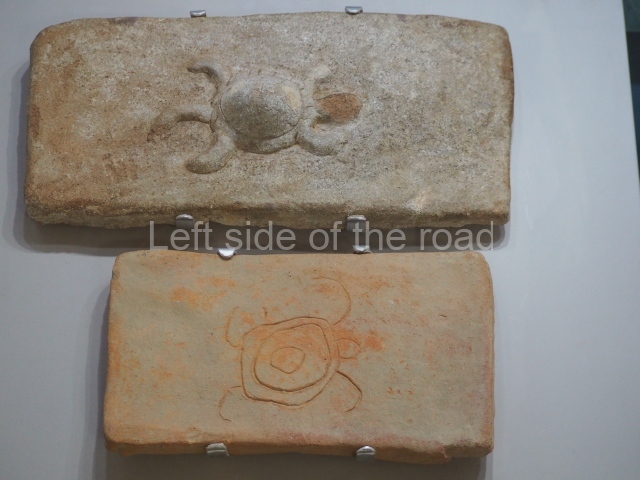

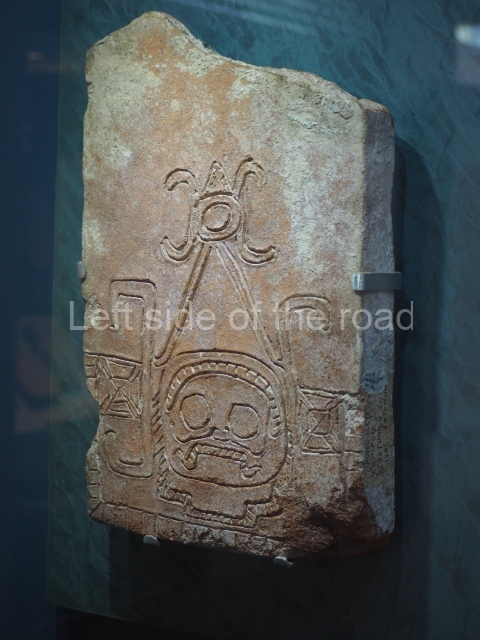

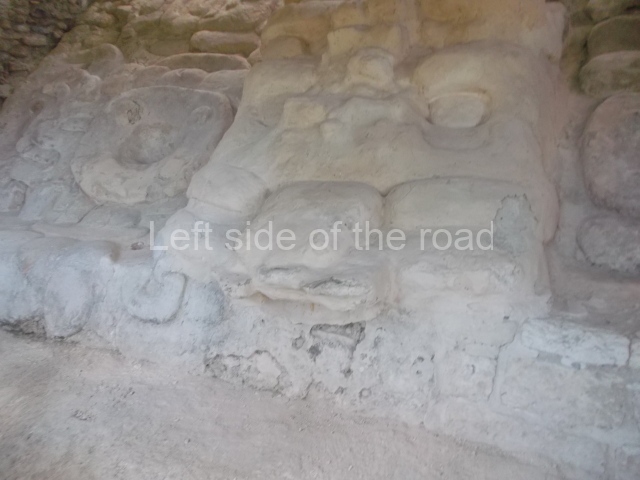

Mask 3 is characteristic of the Late Preclassic: a figure at the centre, probably an iguana-crocodile, with large ear ornaments sprouting serpents on both sides, two figures at the top looking up to the heavens and below a series of plant-like elements. It measures 4 m in height and 7 m in width, and is abutted to the wall of the building in the form of a talud. There are two such masks flanking a broad stairway, but only one of them has been consolidated. This can be divided into three broad sections: a central section featuring the main figure with ear ornaments and serpents on both sides; and above and below these, knots or bows joining the top to upwardly-looking human faces. The face of the mask is that of a mythical animal, possibly a lizard-iguana-feline creature – the elements above the eyes are very characteristic of lizards, as are the double lidded eyes. The nose is flat – the Maya were either unable or unwilling to represent a realistic nose – and it has nostrils at the sides. The mask itself is divided into three parts: the ear ornaments on both sides, the serpents and the human faces. The two sides can also be divided into three parts: the underworld, the earth and the sky, connected by the knots. In addition to symbolising royalty, the ear ornaments might also signify the terrestrial plane, divided into four large sections distributed around a specific point at the centre of the world, the fifth direction. The bows above and below the ear ornaments might well signify the connection between the different worlds – the earth, underworld and sky. These masks conveyed important religious messages for the Maya inhabitants in Preclassic times.

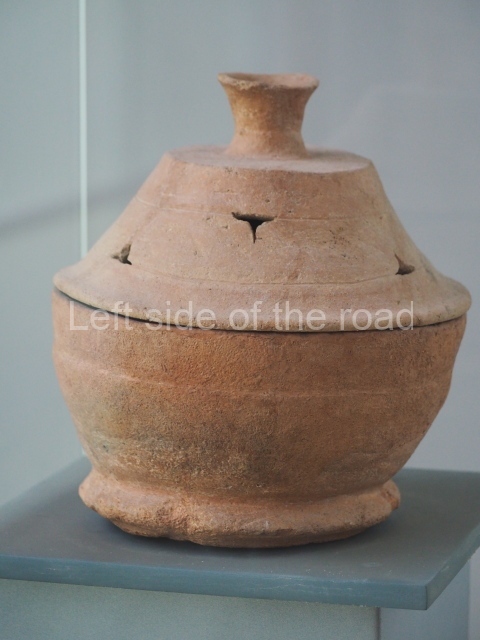

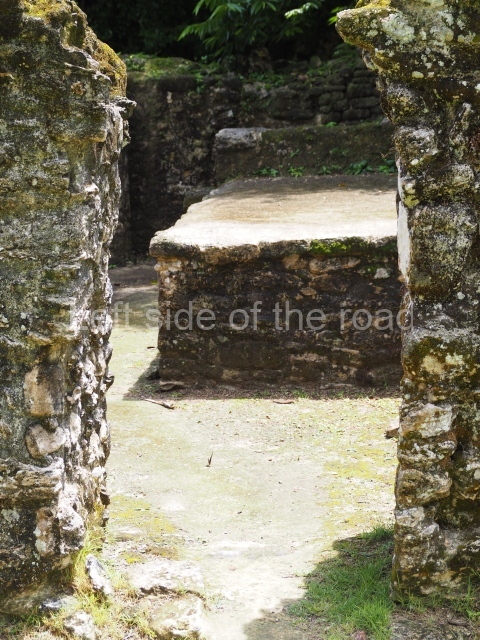

Platform 1a is round and composed of a circular wall which must have subsided due to the weight of the flat roof, causing part of the walls to collapse outwards. The only entrance door faces east. According to the Papeles de Paxbolom Maldonado, one of the principal gods venerated at Itzamkanac was Kukulcan and this temple may well be dedicated to him. The residential palace stands at the south-east corner of Structure 1; the rooms have decorative moulding and the perfectly-preserved walls still stand just over a metre and a half high. The residential unit is composed of various rooms at the top of the building, all of them inter-connected by doors and fronted by a corridor accessed by a stairway. This residential unit is flanked by two independent rooms. The decorative mouldings in the building are in the Rio Bec style, as are the curved walls and the stonework. This building is very important for El Tigre, not only because of the Rio Bec influence but also because it corresponds to the Terminal Classic (AD 900-1100) and boasts Balancan and Altar ceramics, as well as a few examples of the Tinaja Red ceramics characteristic of the region of Calakmul and Rio Bec. There are signs that the building was deliberately destroyed. Part of the mouldings were reused and the rooms were filled with another material.

Structure 4 is the largest construction on the site, measuring nearly 200×200 m and adopting a quadrangular plan. This large platform stands some 10 m above the plaza, forming a type of raised plain on which sit seven mounds of varying sizes and shapes. The main one rises 28 m above the plaza, commencing at the base of the structure, and is possibly the highest mound on the site. Oriented east-west and aligned with the mounds of Structures 2 and 3, it stands 15 m above the base of the large platform, at the middle; it is preceded by a smaller 3-m-high mound. There are other elevations both to the south and north, the most important ones being those of the latter direction – some of these are 3 m high, while the elevations to the south are barely delimited. This is also true of the ones in the north-west, where even the remains of the base can be discerned. The work conducted on Structure 4A can be summarised as follows: the lower part has been delimited and several subsequent platforms covering earlier stages have been found. We believe that the building has had at least four construction phases: the oldest dating from the Late Preclassic, followed by the Early Classic, Terminal Classic and the Postclassic. The stairways also reveal various stages. Opposite Structure 1, in the middle of the Great Plaza, is Structure 5 or the ball court, where the sacbe culminates. This comprises two buildings and a court, the flat space between them. The two parallel structures have a vertical inner wall followed by a talud of varying gradient and stairways or ramps to access the upper part: this is an example of the socalled open variety of ball courts. We believe that some of the walls are from the Late Preclassic, although the construction we see today corresponds to the Terminal Classic and the extensions on the east side to the Late Postclassic.

Importance and relations

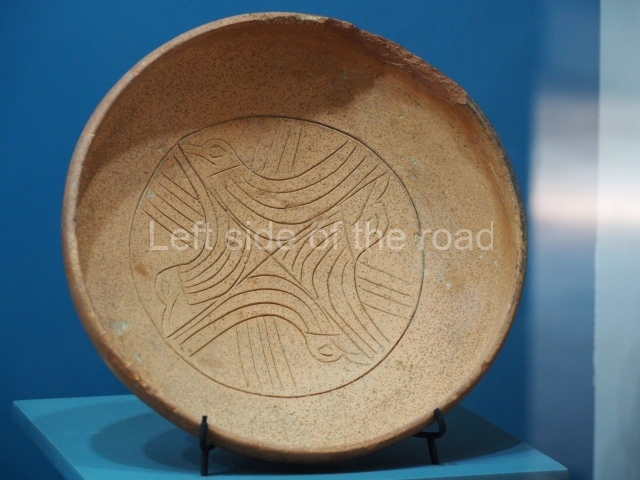

Despite the relatively scant exploration of this area and the fact that it is largely unknown to travellers, the River Candelaria nevertheless played an important role during the pre-Hispanic age as a channel of communication between the two great Maya capitals – Calakmul and Tikal. In the Preclassic period the region appears to have maintained vital links with Peten in Guatemala, as evidenced by the ceramics found and the characteristic masks adorning the architecture. During the Classic period it had greater links with the coast and other Chontal ports such as Xicalango and Potonchan. These links were maintained in the Postclassic, when trade was also pursued with the Yucatan Peninsula. Itzamkanac was a very important fluvial port, albeit situated inland, and its role differed from that of other Chontal ports.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 285-288.

El Tigre – Itzamkanac

1-4. Structures 1 to 4.

How to get there:

From Candelaria. El Tigre is a long way from the nearest major town of Candelaria. There are plenty of taxis that have their rank at the bottom of the main square, opposite the main church. If you are good at bargaining you might be able to get a decent rate to take you there, wait while you visit and take you back to town. You would really need at least an hour for a visit.

GPS:

18d 07’ 15” N

90d 15’ 13” W

Entrance:

M$70

More on the Maya