Museum of the Mayan World

The Petén Regional Museum of the Mayan World

Tayasal Archaeological site –

…. is very much a working site and, in the summer of 2023, there was little for the visitor to see. However, a very complex walkway was close to com0pletion at the time of my visit so there are obviously plans to make the area more visitor friendly.

Location

This site played an important role in the history of the region and is situated at the end of a peninsula, immediately north of the island of Flores. Tayasal lies north of the village of San Miguel, some 150 m above sea level.

History of the explorations

There is some controversy about the location of Tayasal, the ancient capital of the Itza group. Maler was the first person to identify it, in 1910, on the peninsula of the name, although other researchers defended the hypothesis that it must have been situated on the island that the present-day city of Flores occupies. Although there is still a certain amount of doubt, the majority now believe that the island of Flores is too small for the number of settlers that the Spanish conquistadors described in the ancient city, while Tayasal is a much larger and more imposing city with plazas and groups of buildings that accommodated dwellings for thousands of people. The balance is therefore tipped in favour of the Tayasal peninsula.

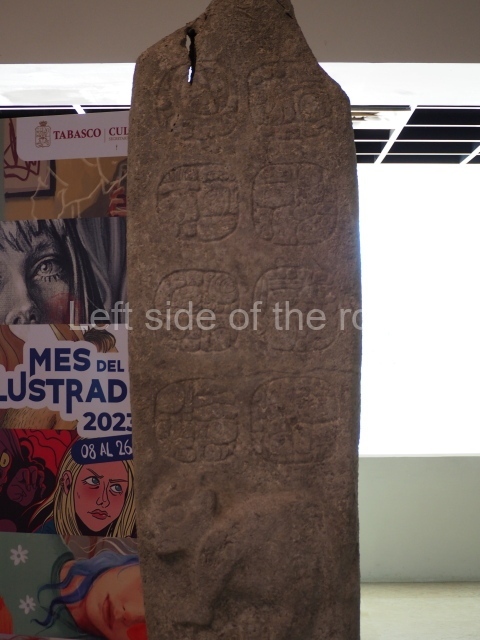

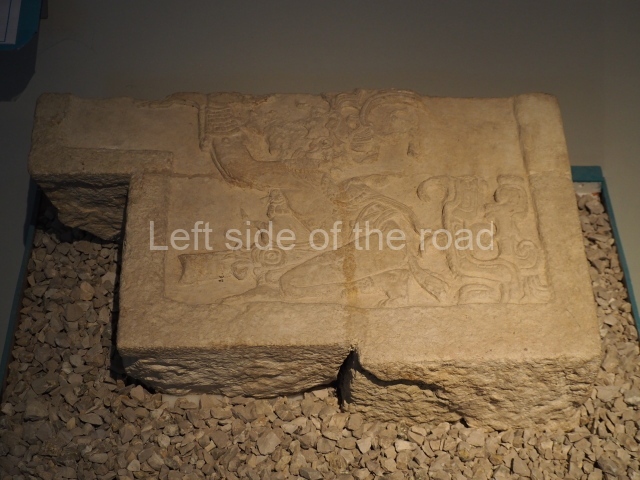

Thanks to the Fifth Letter of Hernan Cortes to the Emperor Charles V, we know that he and his army passed through Tayasal in 1525, en route from Mexico to Honduras to quash a rebellion. Subsequently, there were several forays by Spanish monks and spokesmen to conquer the land, which were all to no avail until 13 March 1597 when Martin de Urzua conquered Tayasal and the environs, subjecting the population to the new political order of the Spanish crown. We also know that prior to this conquest the Spaniards made several visits to the central area of Peten, including an exploratory phase, a propaganda phase and a commercial and military phase, and that all of these took place between Cortes’s visit in 1525 and Urzua’s arrival, the first investigations at the site were conducted in 1910 and 1938 by Teobert Maler, followed by an expedition from the Carnegie Institution in Washington and another by Sylvanus Morley. All of these reported the existence of pyramid temples, temples on platforms mid simple platforms, palaces, astronomical observatories, ball courts, platforms for dancing, plazas with columns, steam baths, adoratoriums, monumental stairways, platforms for theatrical events, causeways, bridges, aqueducts, cemeteries, tombs, ossuaries and stadiums for public entertainment. In 1921 and 1922 the researchers at the Carnegie Institution determined that the structures at the west end of the peninsula were mainly from the Late Classic, although they also recovered odd materials from the Post classic. This was reaffirmed in 1986 when Miguel Rivera Dorado excavated Structure T-100 in Group 23 and determined the existence of construction and funerary features from the Early and Middle Post classic. During the same campaign Stela 3, dated to the Early Classic, was uncovered north of T-100.

Various studies have related the architectural features of the Post classic structures with those at Mayapan, based on the fact that they include benches along lateral and rear walls that were used for family fidoratoriums. The elongated buildings and open, more elaborate halls have masonry columns that once supported roofs made of perishable materials. These were found near the main temples. In 2004 new excavations were conducted in Group 23, specifically structures T-95 and T-99B, and the conclusion was reached that both contain Post classic architecture. T95 is a rectangular platform on which stands a room with three west-facing entrances, while T-99B is also a rectangular platform but with C-shaped benches and open at the front. Burial 1, discovered under the central stairway, contains a fragment of a vessel that confirms the site’s occupation in the middle or late Post classic. Other similar constructions have been found in central Peten, at sites such as Topoxte, Zacpeten, Macanche, Ixlu, Candelaria and Punta Nictun.

Pre-Hispanic history

This site represents the last enclave in the Maya region which after several failed attempts was finally subjected to the Spanish army in 1697, much later than the conquest of the Guatemalan plateau region in 1524 and the north of the Yucatan Peninsula in 1531. Tayasal, the capital of the Itza group, therefore had a much later occupation that the other sites in the region. Archaeological research supports the hypothesis of a long occupation stretching from the Middle Preclassic (800 BC) to the beginning of the 18th century.

Site description

The site was declared a National Monument by government decree on 24 April 1931. It comprises 11 sections: 1. Tayasal Main Group. 2. North Central Tayasal. 3. Tayasal Cove. 4. North-West Tayasal. 5. West Tayasal. 6. South-East Tayasal. 7. Trapiche Point. 8. West San Miguel. 9. San Miguel Aguada or natural depression. 10. East San Miguel. 11. El Jobito. The protected area is bounded to the north and west by Lake Peten Itza and to the east and south by the village of San Miguel. The site boasts more than 200 structures associated with ceremonial plazas and residential groups. There are plazas with large, open courtyards for public spaces, palace-type buildings, pyramids, residential precincts, fortified walls and a cenote or natural well.

Juan Antonio Valdes and Miriam Salas

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp226-228

Getting there:

From Flores. Take the colectivo launch from the closest point of the island to San Miguel. Cost – Q10. The site is off the road that comes up from the dock. Turn left at the corner of the football pitch and then left again after about 200m.

There’s not a great deal to see at Tayasal as what is of interest is currently a working archaeological site. There are many ‘explorations’ taking place around the central area. There are obviously plans to make the site more visitor friendly as in the summer of 2023 the authorities were in the process of constructing a very extensive wooden walkway system which would allow visitors to look down on what had been already uncovered.

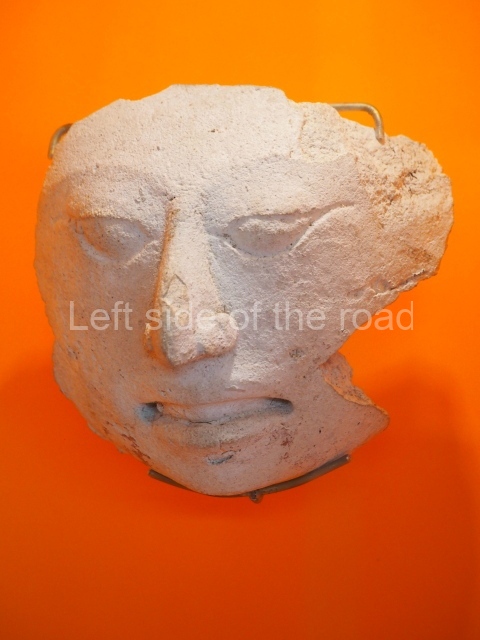

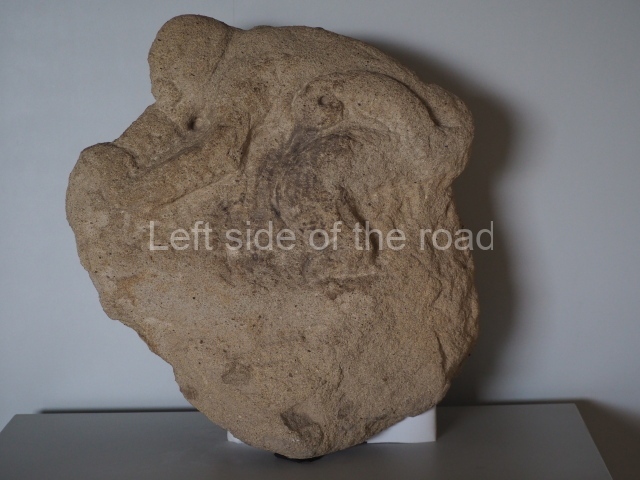

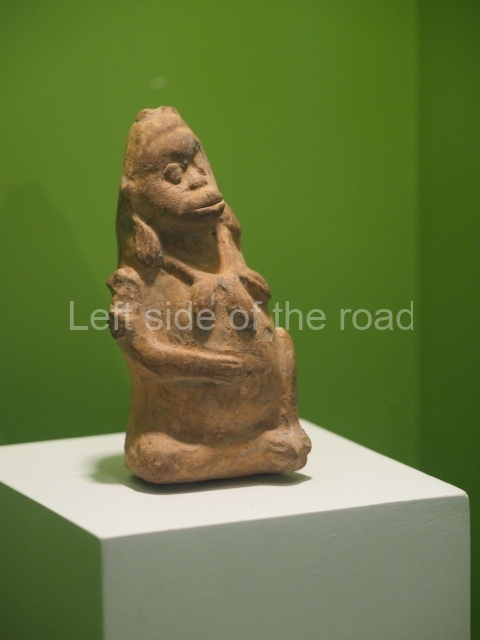

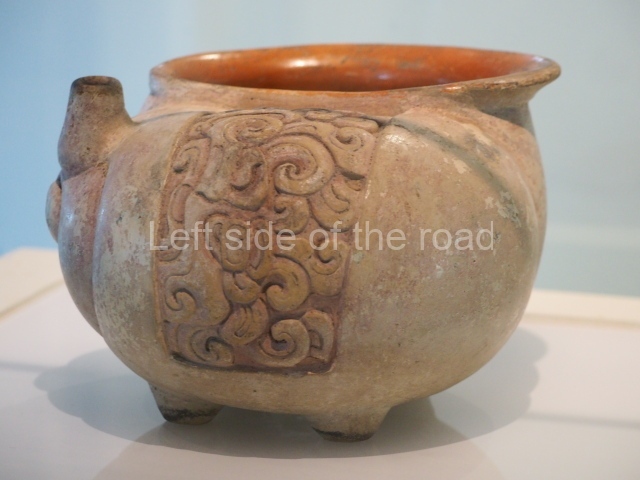

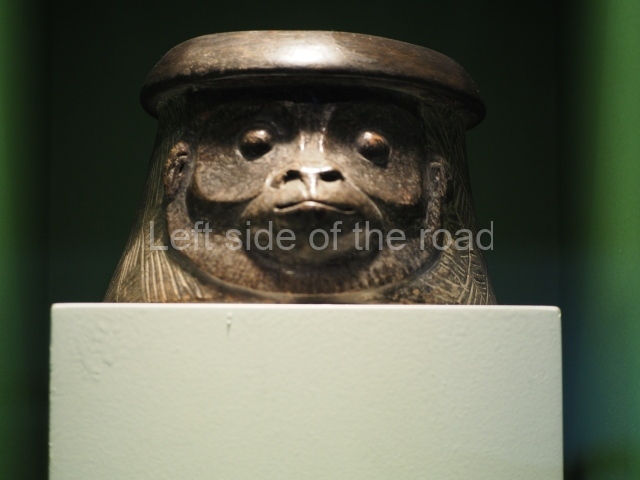

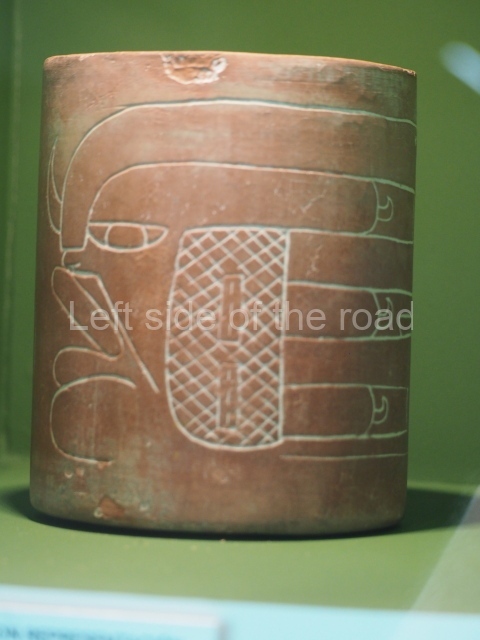

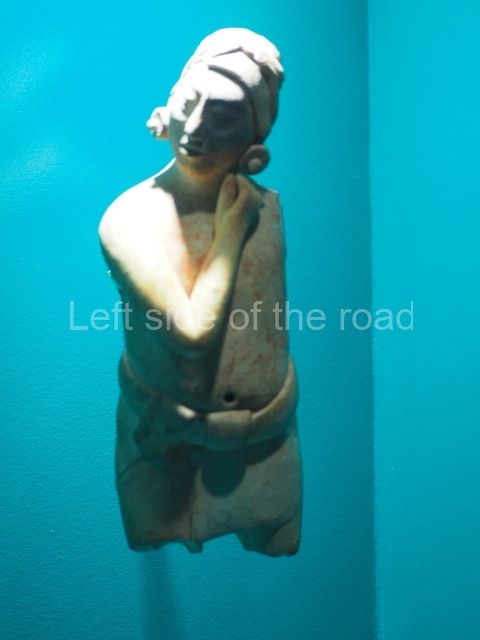

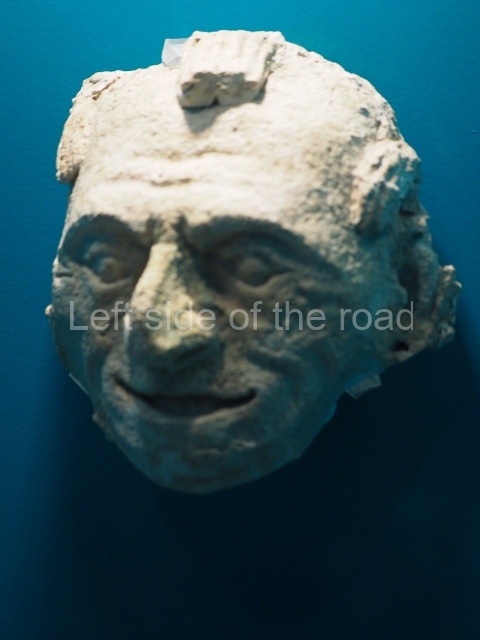

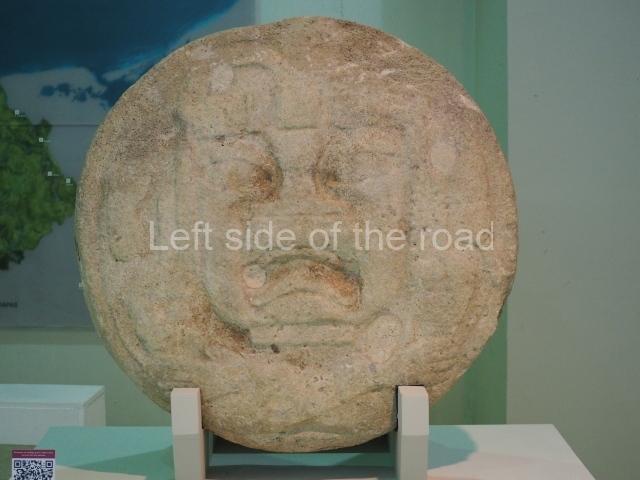

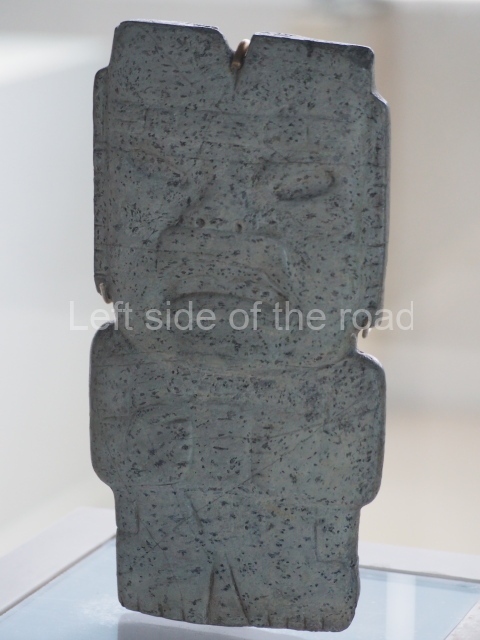

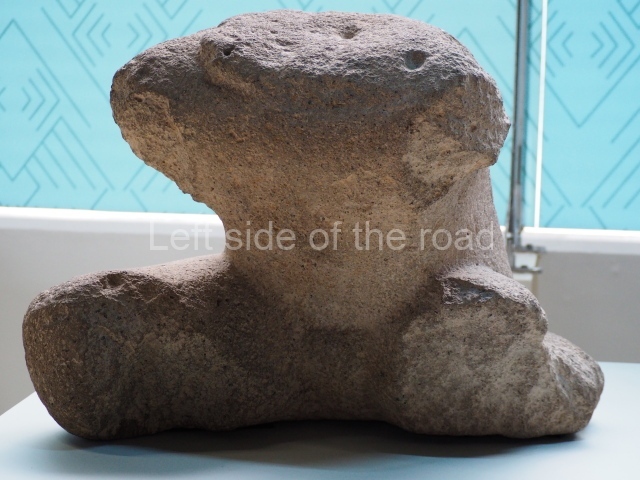

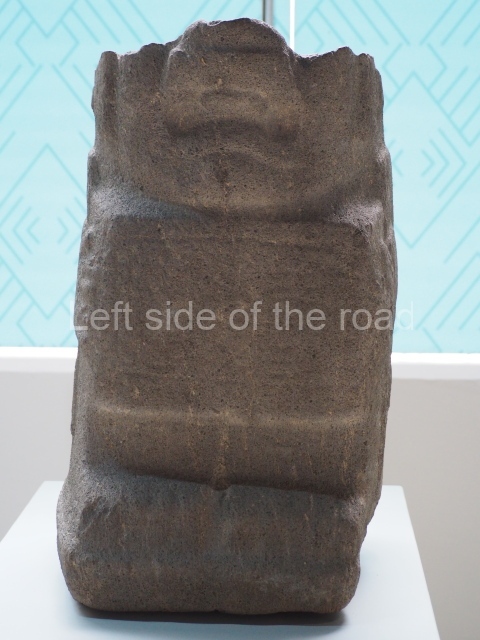

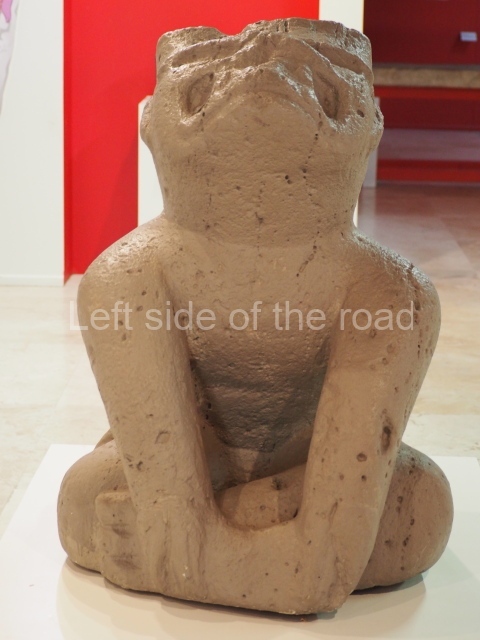

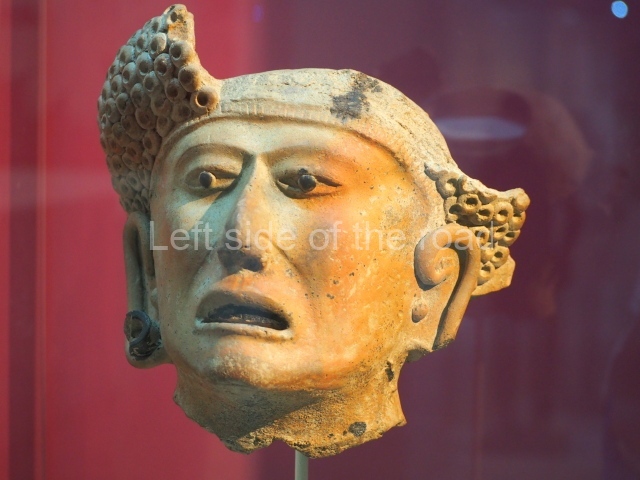

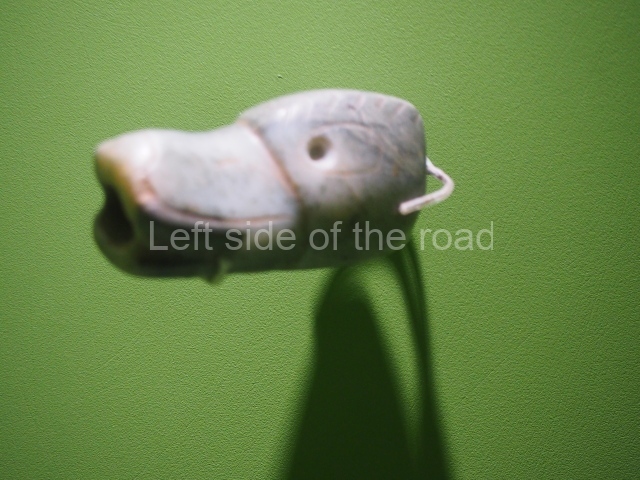

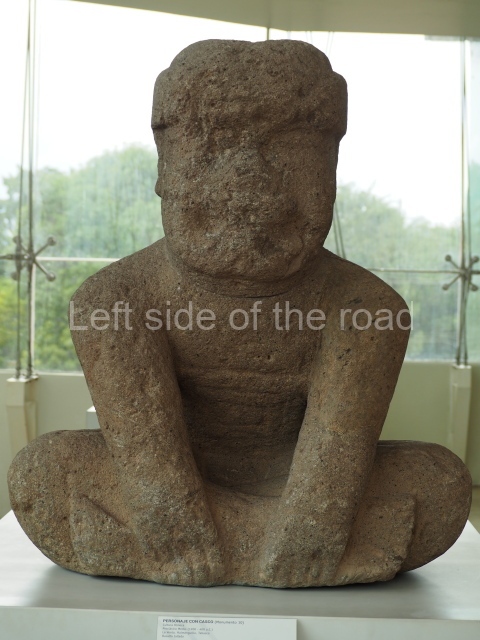

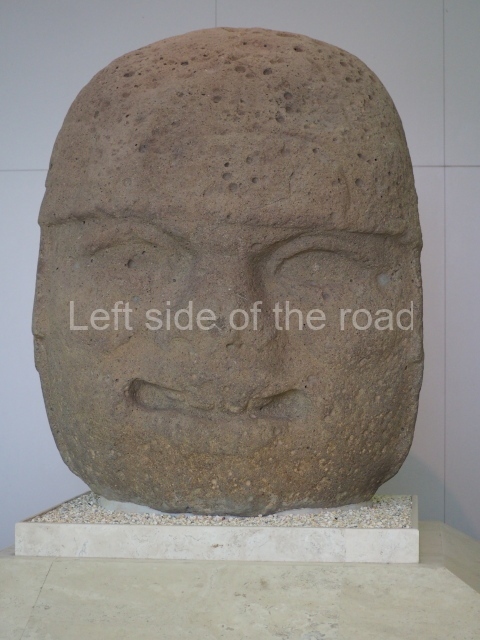

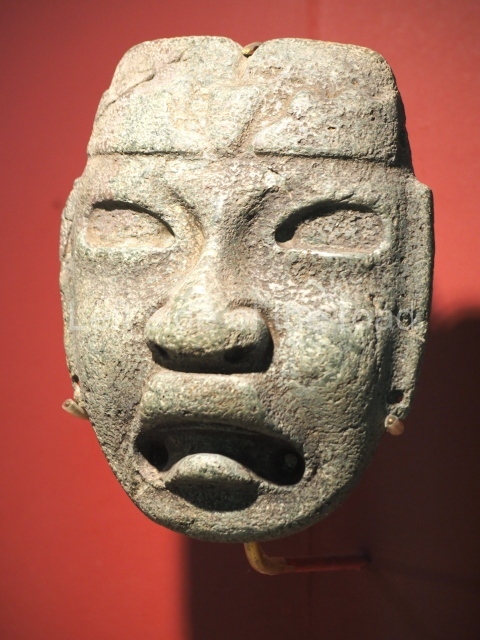

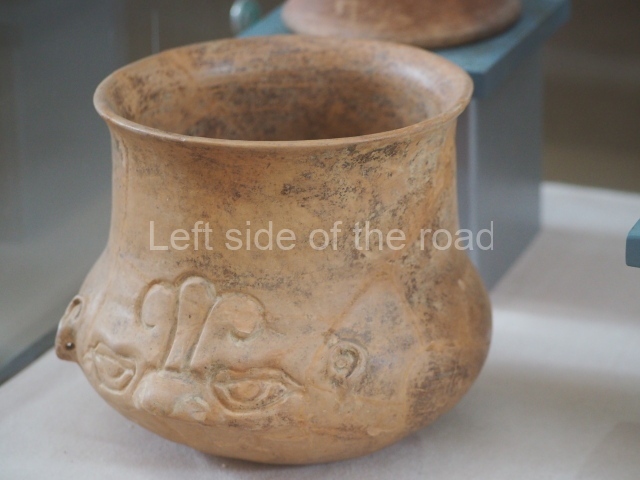

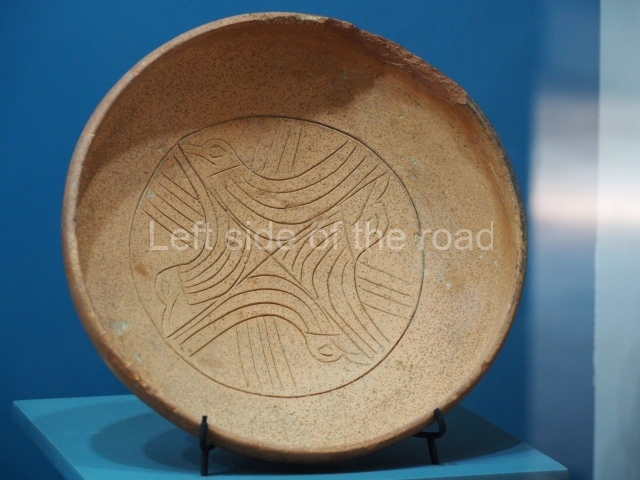

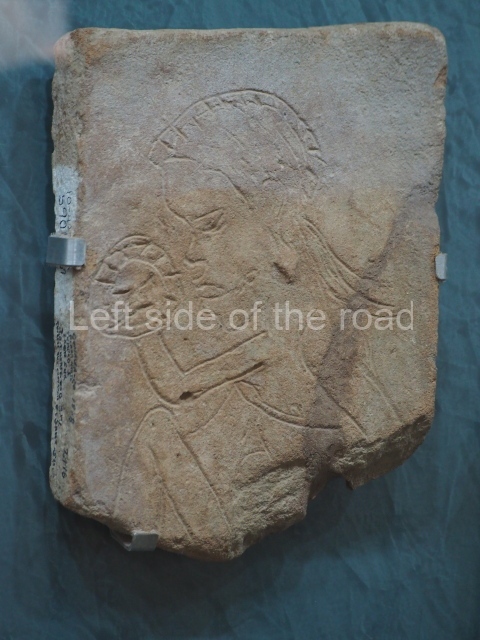

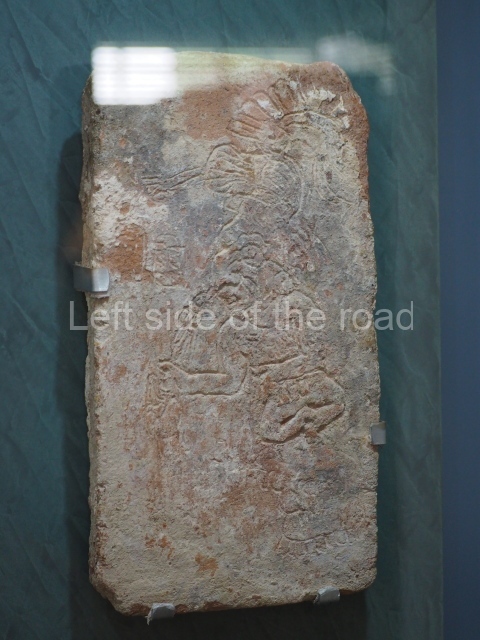

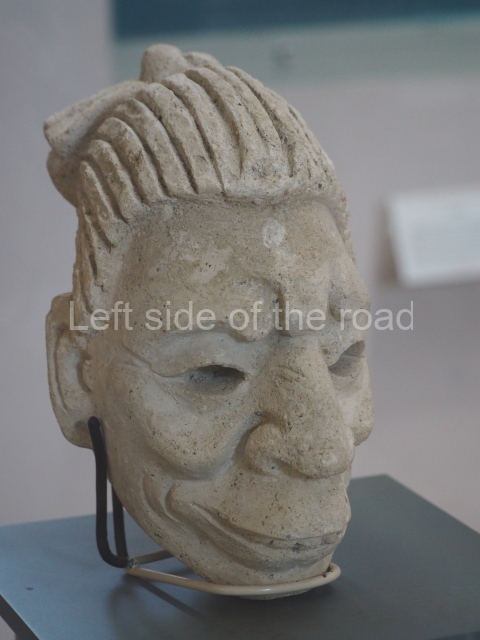

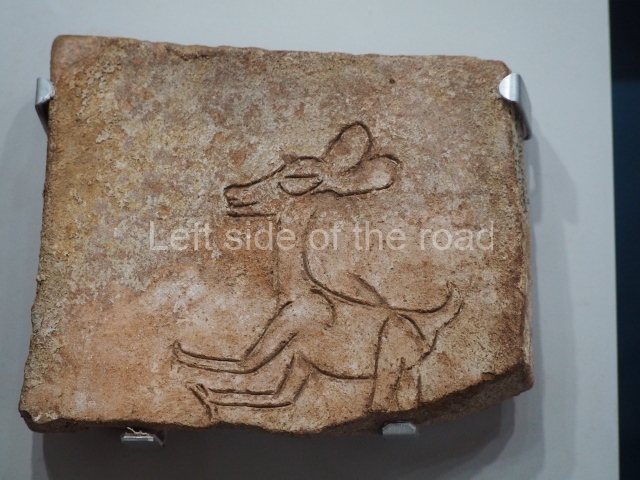

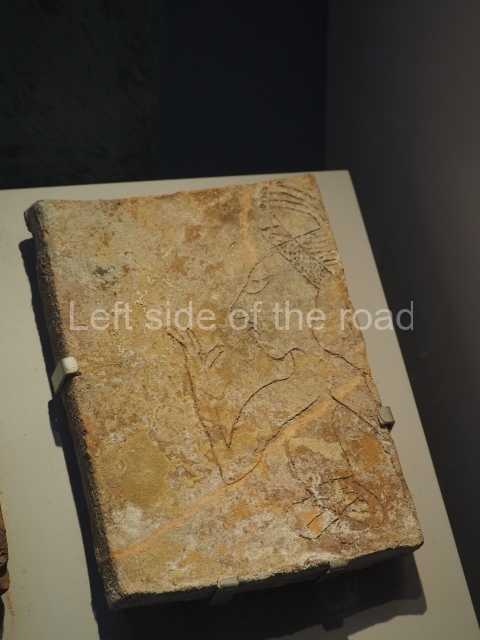

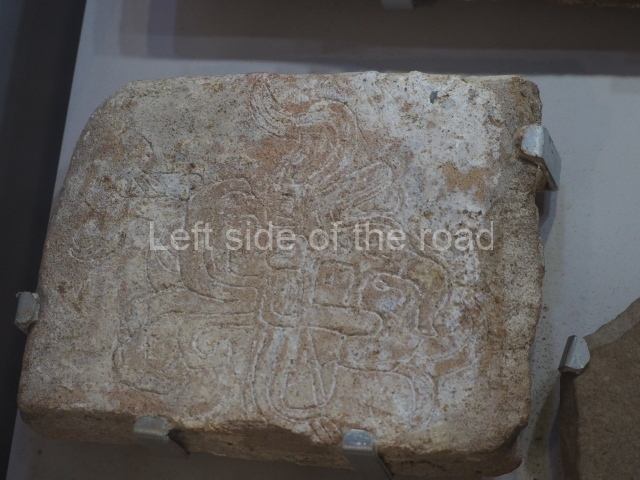

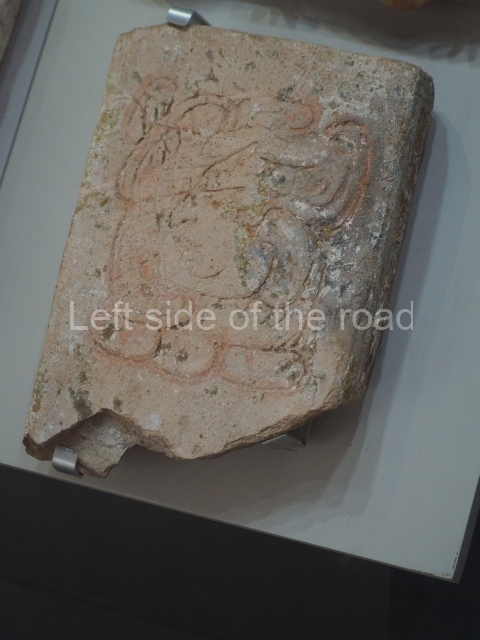

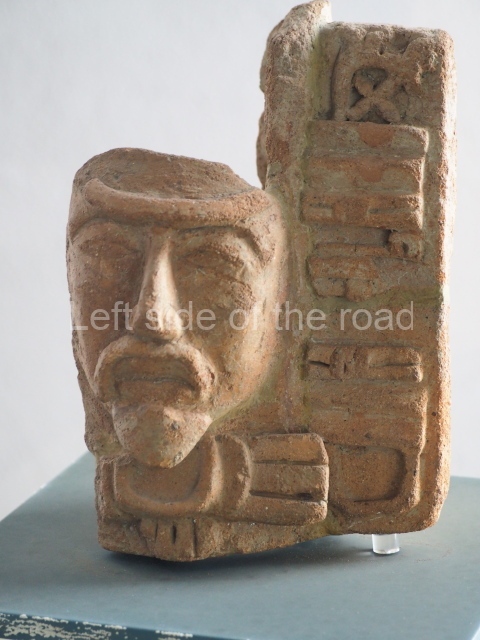

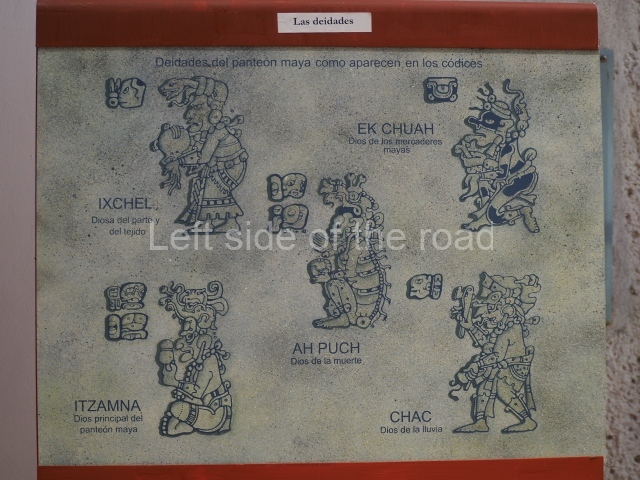

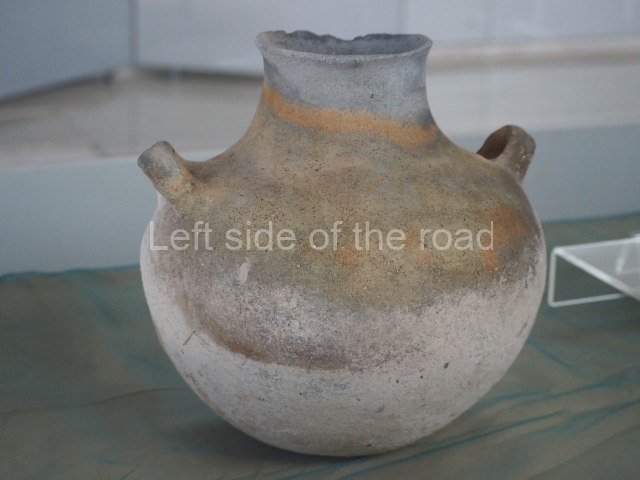

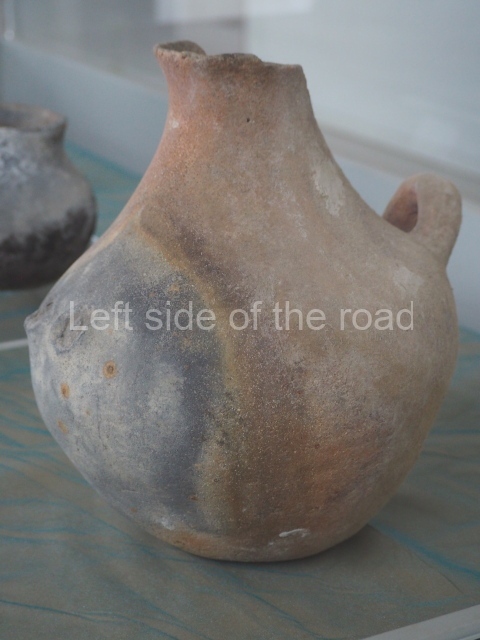

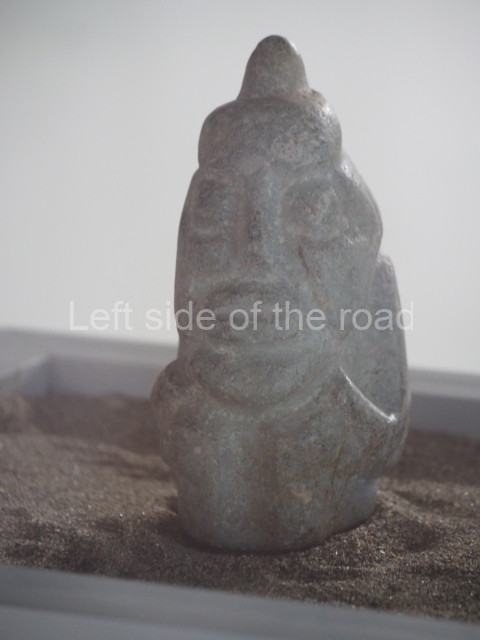

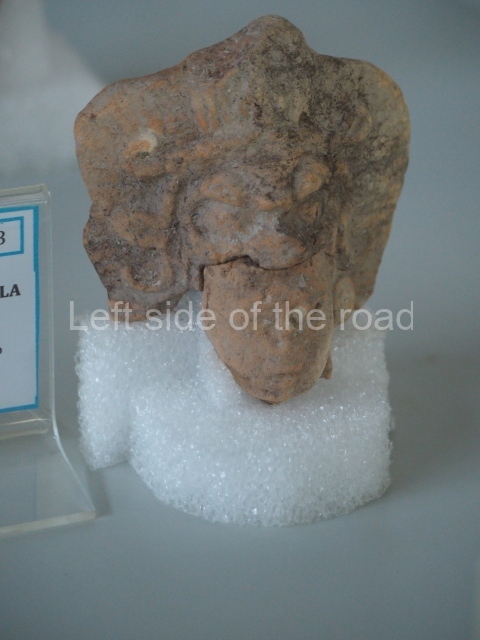

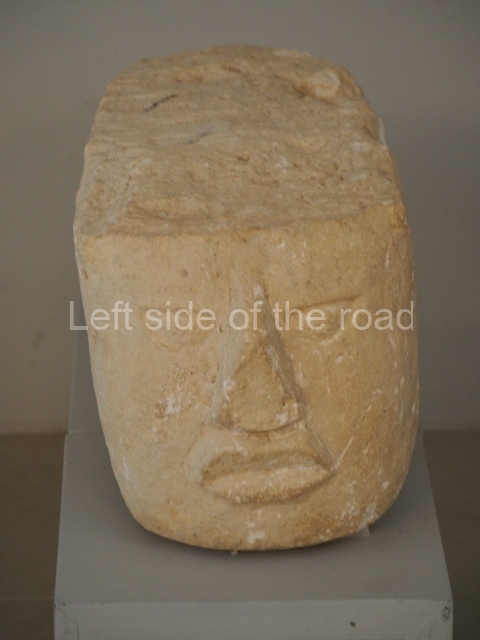

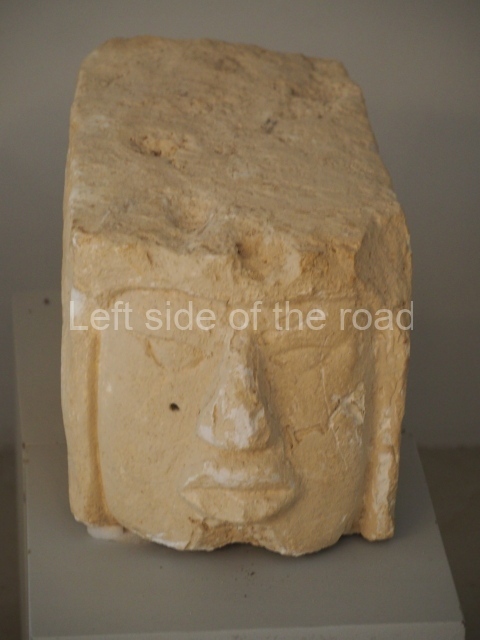

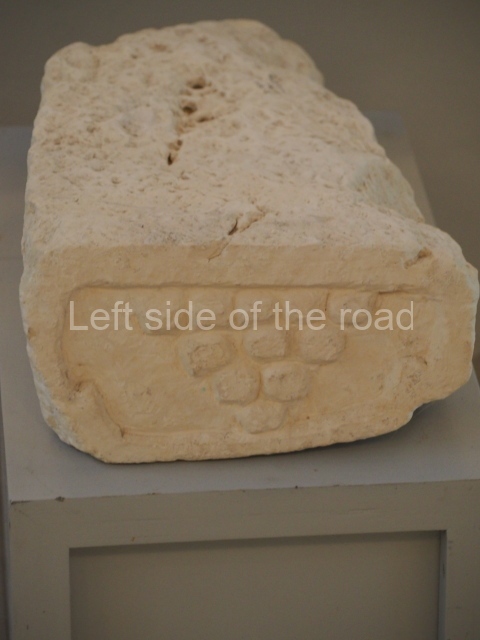

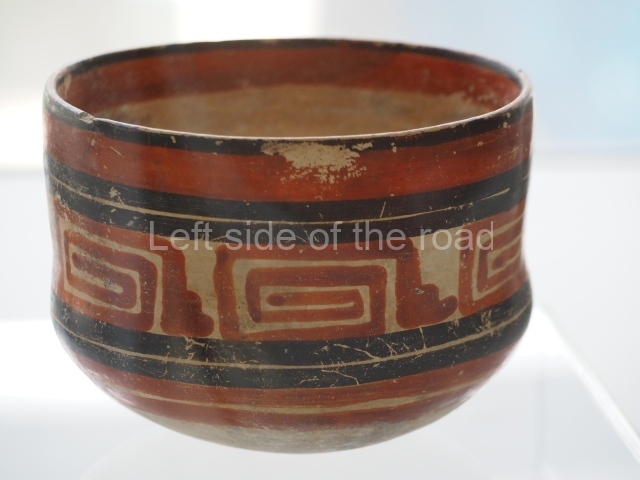

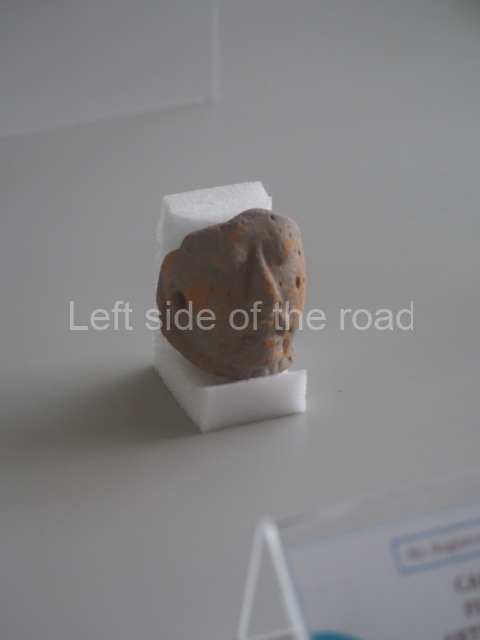

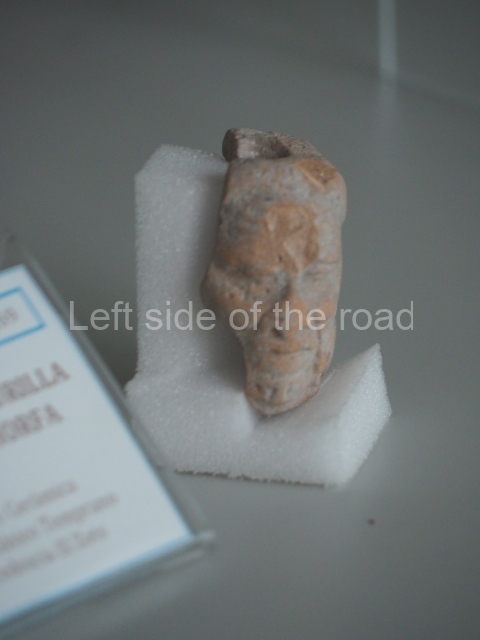

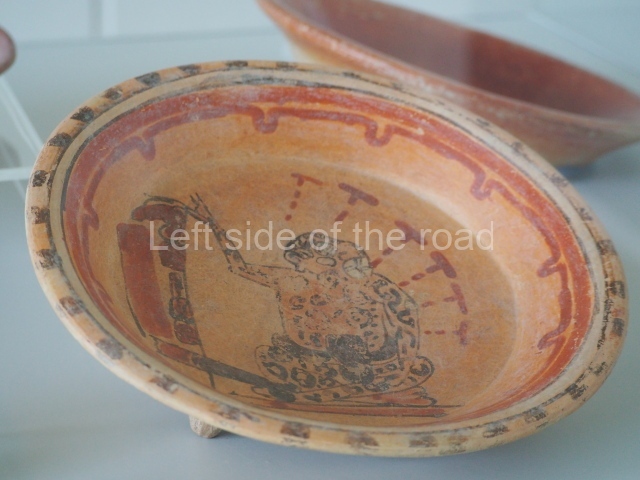

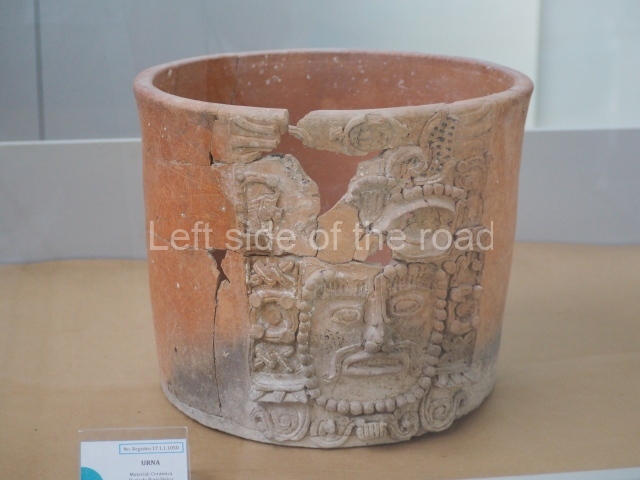

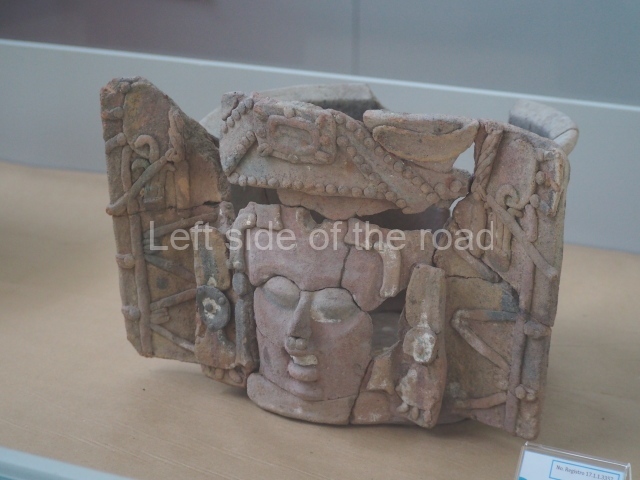

Petén Regional Museum of the Mayan World

However, what is of interest is the town’s museum. This is in a structure which is also the towns cultural centre. This is about a 15 minute walk from the landing stage for the launches from Flores. Go up the steep street directly behind the Stone Horse (at the dock) and keep straight ahead. The Museum is on the left hand side – just after a bar with a Gallo sign outside on the right.

Entrance is free.

Be careful if visiting on a Monday. Most state museums are closed that day.