Frederick Engels

The Great ‘Marxist-Leninist’ Theoreticians

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Collected Works

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels – Writings, compilations and analyses

Ukraine – what you’re not told

Frederick Engels – pamphlets, books and commentaries

Virtually everything that has been published by Frederick Engels is included in the 50 volume Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.

However, his contribution to the world revolutionary movement has meant that many of his most significant works have been produced as individual pamphlets/books. The intention is to post as many of those as possible on this page.

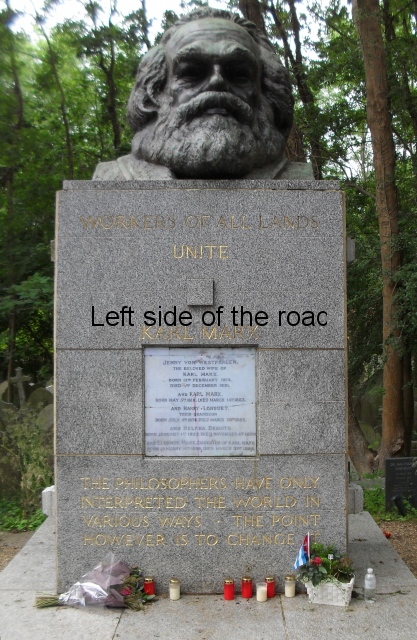

Engels spent many years of the 19th century in Manchester – and a few years ago returned to stand proudly in a public square.

Socialism, Utopian and Scientific, Charles Kerr, Chicago, 1908, 139 pages.

Principles of Communism, The Little Red Library, No 3, Daily Worker Publishing Company, Chicago, 1925, 32 pages.

The Peasant War in Germany, Allen and Unwin, London, 1927, 190 pages.

Germany, Revolution and Counter Revolution, Martin Lawrence, London, 1933, 155 pages.

The Housing Question, Martin Lawrence, London, ND, 1930s?, 103 pages. (Some markings.)

A Handbook of Marxism, with selections from the works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, International Publishers, New York, 1935, 1082 pages,

Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution In Science – Anti-Dühring, International Publishers, New York, 1939, 365 pages.

On Historical Materialism, International Publishers, New York, 1940, 30 pages. Little Marx Library.

Ten Classics of Marxism, Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, International Publishers, New York, 1940, 785 pages.

Ludwig Feuerbach and the outcome of Classical German Philosophy, International Publishers, New York, ND, 1940s?, 101 pages.

The Housing Question, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1942, 100 pages. Volume Seven of The Marxist-Leninist Library.

Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1943, 149 pages. From Project Gutenberg website.

The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1943, 216 pages.

On Capital, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1944, 136 pages.

Dialectical and Historical Materialism, edited by LL Sharkey and S Moston, Current Book Distributors, Sydney, 1945, 152 pages.

Dialectics of Nature, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1946, 383 pages.

The Condition of the Working Class in England, Allen and Unwin, London, 1950, 300 pages.

Anti-Duhring, Herr Eugen Duhring’s Revolution in Science, FLPH, Moscow, 1954, 546 pages.

Engels as Military Critic, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1959, 146 pages. Reprinted from Volunteer Journal and the Manchester Guardian of the 1860s. With an introduction by WH Chaloner and WO Henderson.

F Engels, Paul and Laura Lafargue, Correspondence Volume 1, 1868-1886, FLPH, Moscow, 1959, 407 pages.

F Engels, Paul and Laura Lafargue, Correspondence Volume 3, 1891-1895, FLPH, Moscow, 1959, 635 pages.

Articles from the Labour Standard (1881), Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1965, 53 pages. The Labour Standard was a British trade union weekly published in London from 1881 to 1885, edited by J Shipton.

The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1968, 16 pages.

Socialism – Utopian and Scientific, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1968, 74 pages.

Socialism, Utopian and Scientific, Frederick Engels, November 8th Publishing House, Ottawa 2023, 129 pages.

The role of force in history, Frederick Engels, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1968, 108 pages.

Ludwig Feuerbach and the end of Classical German Philosophy, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1969, 61 pages.

History of Ireland (to 1014), Irish Communist Organisation, Dublin, 1970, 68 pages.

On an Article by Engels, (Dublin, ICO, 1971), 23 pages.

The Bakuninists at work – Review of the Uprising in Spain in the summer of 1873, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1971, 28 pages.

Critique of the Erfurt Programme, British and Irish Communist Organisation, Glasgow, 1971, 20 pages.

On Marx’s Capital, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1972, 126 pages.

Dialectics of Nature, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1972, 403 pages.

Ludwig Feuerbach and the end of Classical German Philosophy, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1973, 68 pages. Scientific Socialism Series.

Marx, Engels and Lenin on the Irish Revolution, Ralph Fox, The Cork Workers Club, Cork, 1974, 36 pages.

Marx, Engels and Lenin – On the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1975, 41 pages.

Marxism and the Liberation of Women, Quotations from Karl Marx, Frederick Engels, VI Lenin, Joseph Stalin and Mao Tse-tung, Union of Women for Liberation, London, n.d., mid-1970s?, 64 pages. Includes a statement of aims of the Union of Women for Liberation.

Socialism – Utopian and Scientific, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1975, 108 pages.

The part played by labour in the transition from ape to man, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1975, 25 pages.

On Marx, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1975, 26 pages.

The Peasant Question in France and Germany, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1976, 29 pages.

Ludwig Feuerbach and the end of Classical German Philosophy, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1976, 185 pages. Has the same content as the two Soviet Revisionist editions on this page but also has, in addition, Plekhanov’s Forewords and Notes to the Russian Editions of the Engels pamphlet. (There’s a strange comment in the Publisher’s Note at the very beginning of the book. This states, after giving reference to the source material of Plekhanov’s Appendices, that they were included ‘with numerous and often drastic revisions and corrections where necessary’.)

Marx-Engels-Lenin, On Scientific Communism, FLPH, Moscow, 1967, 537 pages.

On Scientific Communism, Marx, Engels and Lenin, Progress, Moscow, 1976, 537 pages.

On Dialectical Materialism, Marx, Engels and Lenin, Progress, Moscow, 1977, 422 pages.

The Woman Question, Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, International Publishers, New York, 1977, 96 pages.

Principles of Communism, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1977, 28 pages.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels – Selected Letters, Foreign Languages Press, Peking, 1977, 133 pages.

Anti Duhring, Progress, Moscow, 1977, 519 pages.

The Housing Question, pp 317-391, Marx and Engels Collected Works, Volume 23, 75 pages.

The Peasant War in Germany, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977, 208 pages.

The Wages System, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977, 56 pages.

Marx and Engels – On Reactionary Prussianism, Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute, Moscow, Red Star Press, London, 1978, 48 pages. Reprint of the original from the Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1943.

Condition of the working class in England, Progress, Moscow, 1980, 307 pages.

On Engels’s The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, IL Andreyev, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1985, 159 pages.

The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, in the Light of the Researches of Lewis H. Morgan, with an introduction and notes by Eleanor Burke Leacock, International Publishers, New York, 1993, 285 pages.

The Condition of the Working Class in England, Marxist Internet Archive, 1998, 187 pages.

Socialism Utopian and Scientific, Foreign Languages Press, Paris 2020, 96 pages.

The Housing Question, Foreign Languages Press, Paris, 2021, 103 pages.

Biographies

Frederick Engels, a biography, Gustav Mayer, Knopp, New York, 1936, 344 pages.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, D Riazanov, International Publishers, New York, n.d., 1940s, 224 pages.

Frederick Engels, a biography, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1974, 511 pages.

Frederick Engels, a biography, Progress, Moscow, 1982, 560 pages.

Frederick Engels, a short biography, Evgeniia Akimovna Stepanova, Progress, Moscow, 1988, 302 pages.

Frederick Engels, his life, his work and his writings, Karl Kautsky, Charles Kerr, Chicago, 1899, 32 pages.

The Great ‘Marxist-Leninist’ Theoreticians

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Collected Works

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels – Writings, compilations and analyses