More on the Maya

Nim Li Punit – Belize

Location

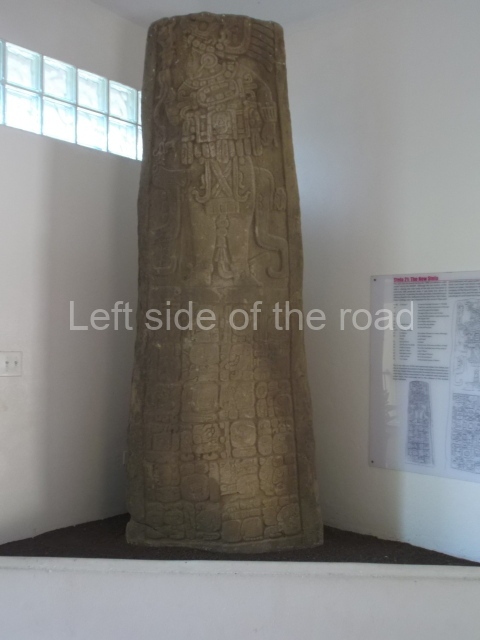

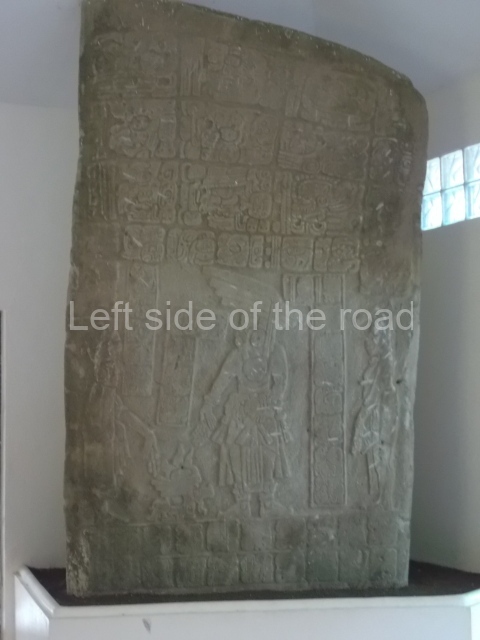

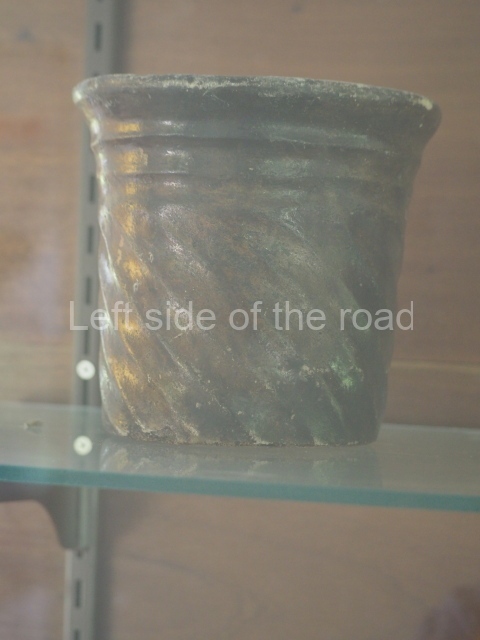

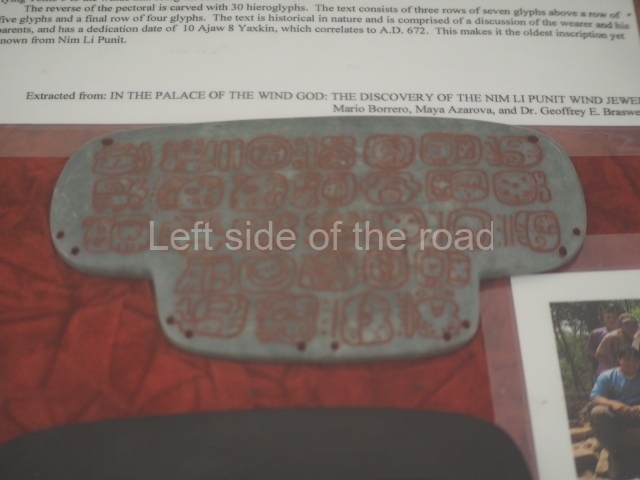

This settlement from the Late Classic period (AD 600- 800) is situated south of the Golden Stream basin on a natural elevation in the Maya Mountain foothills known as the Toledo Beds, a complex series of sedimentary, sandstone and slate rocks from the Oligocene and more recent limestone from the Cretacious period. Towards the east, the coastal plain stretches to the Caribbean and there are maize fields with hardly any rainforest in the area around the site; running along both ends of the hill on which it sits are small streams that the ancient Maya used for their own consumption and for irrigation purposes, just like their modern descendants today. The site is located near the village of Indian Creek, some 50 km from the town of Punta Gorda in the Toledo district, and 1.5 km west of the Southern Highway, mile 75. The site has a small museum for safeguarding the stelae with reliefs and hieroglyphic inscriptions, earthenware vessels and figurines, and other minor discoveries.

History of the explorations

The initial investigations in 1976 were undertaken by Norman Hammond of the University of Cambridge and Barbara McLeod of the University of Texas at Austin, who studied the iconography of the sculpted monuments and their hieroglyphic inscriptions; as a result of this research a map of the pre-Hispanic settlement was drawn up, the monuments were classified and the principal group was excavated. In 1983, as part of his survey of southern Belize, Richard Leventhal excavated the upper plaza on behalf of the Belizean government and with foreign funding. In 1986 he identified another stela and a royal tomb containing the remains of five individuals as well as over 35 ceramic vessels and countless grave goods.

Site description and monuments

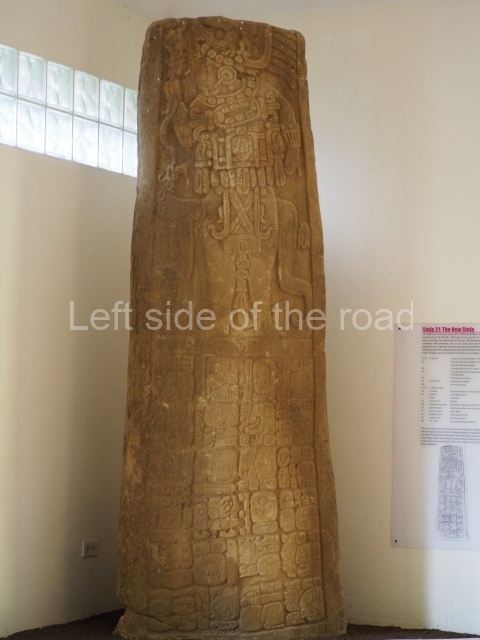

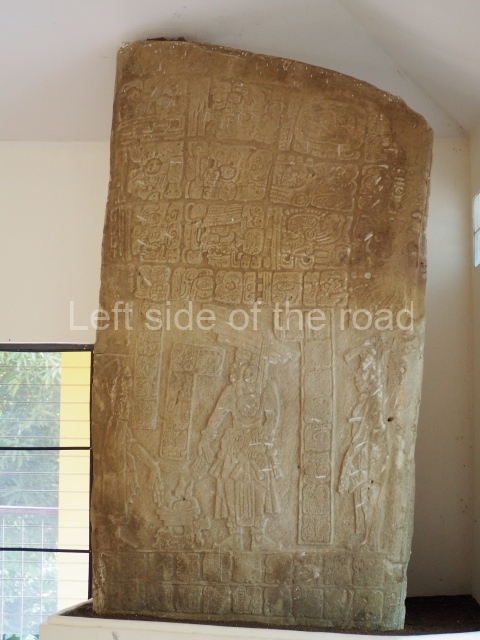

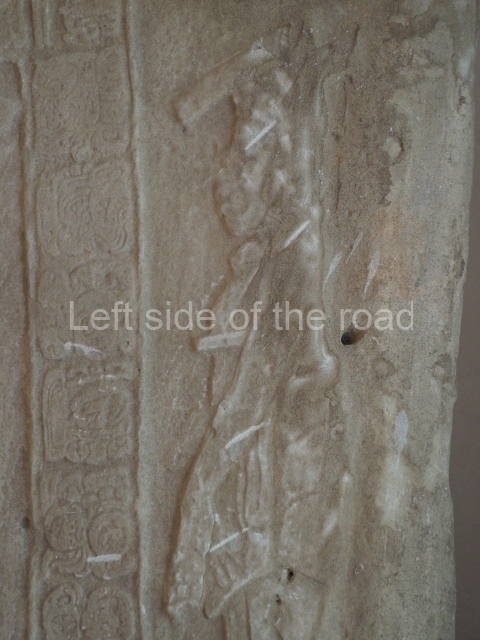

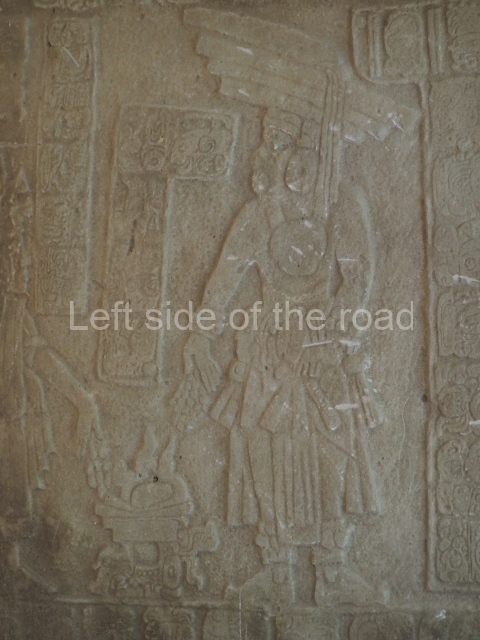

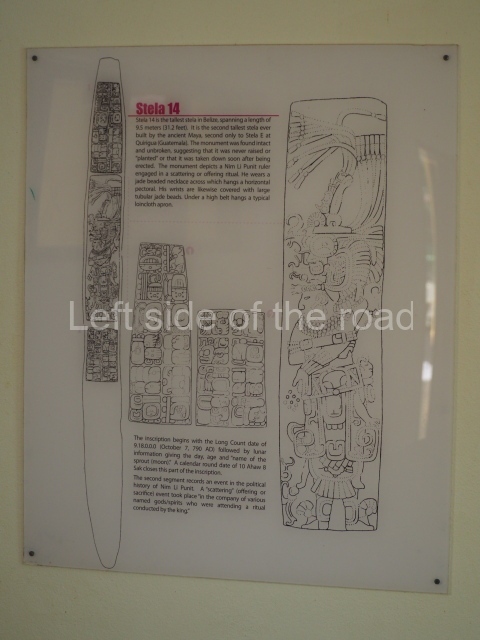

The name Nim Li Punit is Kekchi Maya for ‘Big Hat’ and was assigned by Joseph Palacio, the Archaeological Commissioner for Belize at the time the site was discovered by oil company workers in 1976. It makes reference to the prominent headdress of the figure depicted on Stela 14. Although Nim Li Punit has neither the impressive architecture nor the exquisite stonework to be found at Lubaantun, it is relatively similar in general terms and compensates for these omissions with a collection of 26 stelae, seven of which are sculpted; the largest is Stela 14, which at 9.5 m is the longest discovered in Belize and the second longest monument in the Maya area after Stela E at Quirigua. This site was initially believed to be a secondary centre dependent on Lubaantun, but archaeological studies have demonstrated that it was a large settlement and must have served as the ceremonial centre for the surrounding population. Even so, its relationship with other large centres in Belize and southern Peten remains unclear.

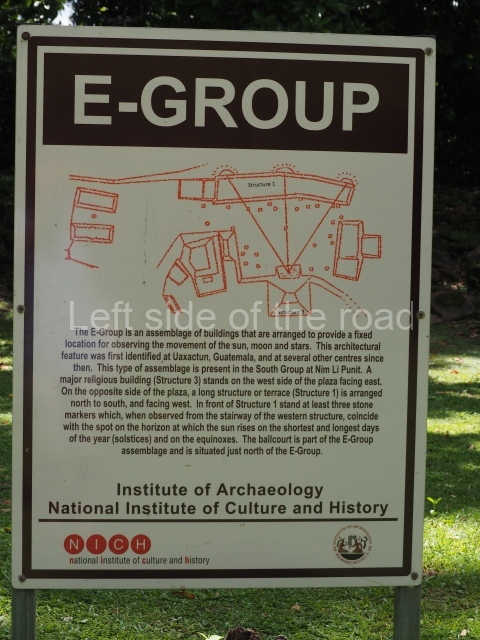

The principal constructions are distributed on the crest of a group of low hills and comprise three groups: a ceremonial complex and two civic-residential groups for the ruling elite, situated north of the main group. The ceremonial precinct is composed of two plazas, one of which stands 4 m higher than the other. The stelae were erected in the lower, and larger, of the two plazas. This plaza is in turn situated approximately 5 m above the natural level of the terrain and the various stepped sections of the platform provided access to the main group via a ramp or stairway. The largest pyramid structure stands some 11m high, while another measures 65 m in length and 3 m in height. The upper, smaller plaza is delimited by the large pyramid, two square-plan pyramid structures – one of these (structure 7) contained a rich collective tomb excavated by Leventhal in 1985 – and three elongated platforms, two small ones and a longer one at the west end measuring 40 m in length and 2 m in height. The north-east end of this plaza opens on to the Ball Court, situated a few metres below these two platforms. The court is open-ended and approximately 20 m in length, with a smooth, circular marker at its centre. North-west of the Ball Court, in the West Group, the hill slopes were levelled with retaining walls to create two terraces on which stand low platforms and a pyramid structure 6 m high, which due to its topographical position is the most imposing construction of the group, despite not being excessively high. East of the West Group and north of the Ball Court lies the East Group, composed of various stepped terraces on which are numerous residential structures; the highest terrace resembles a small irregular plaza, delimited by four pyramids and various smaller mounds.

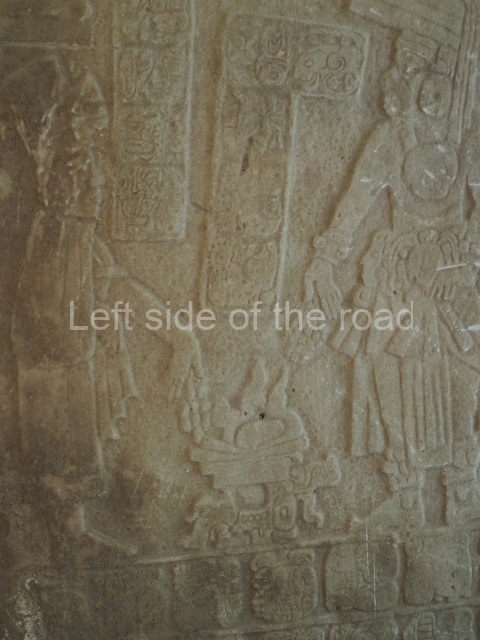

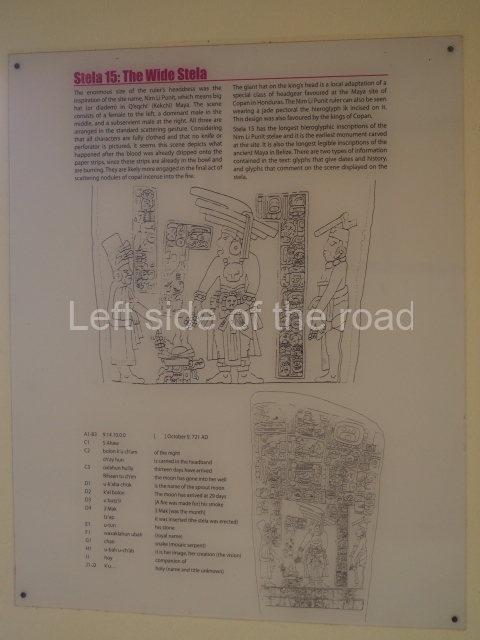

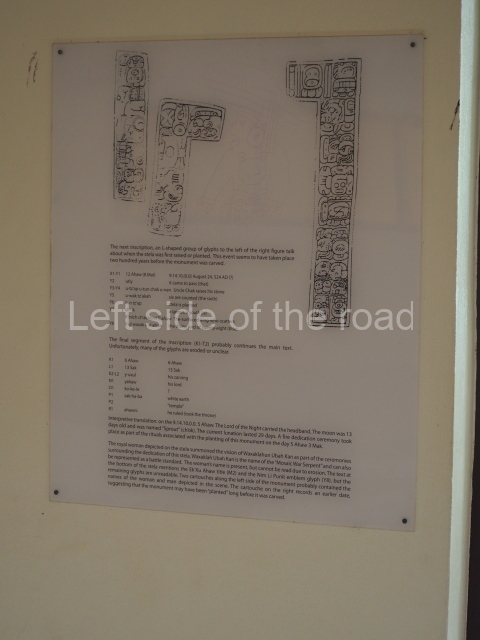

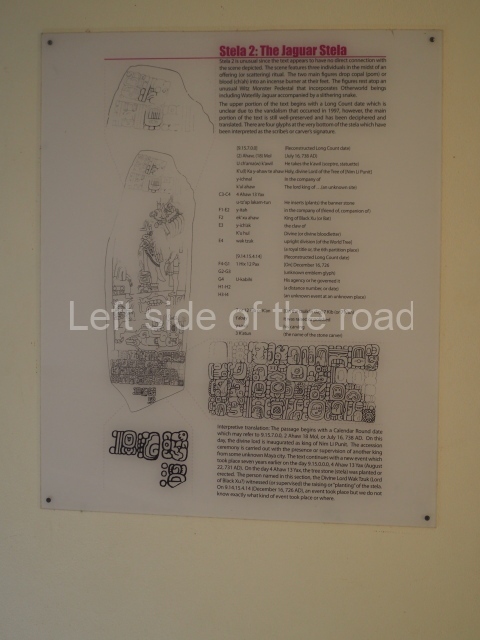

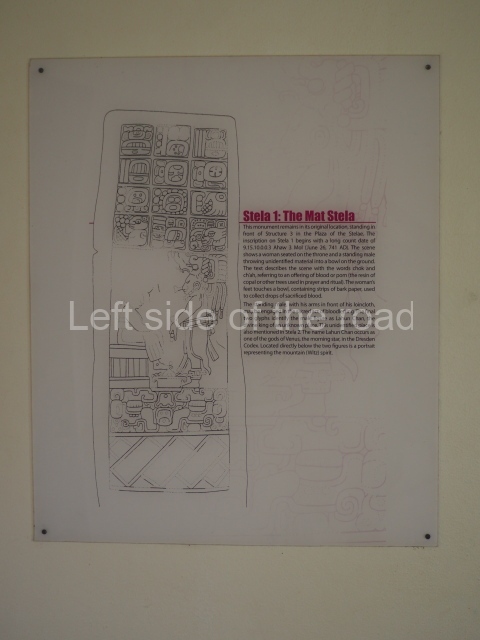

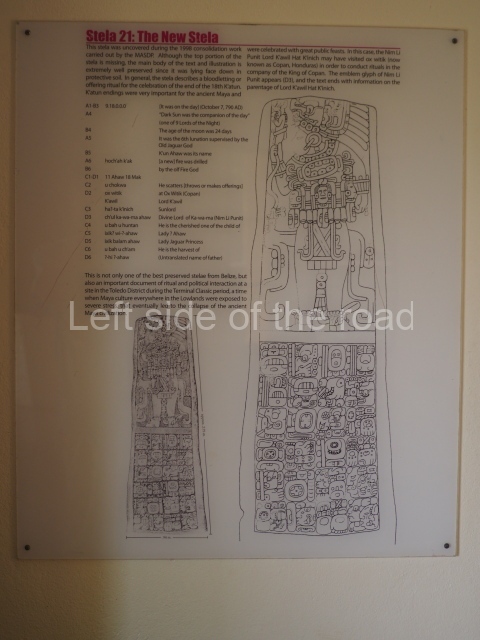

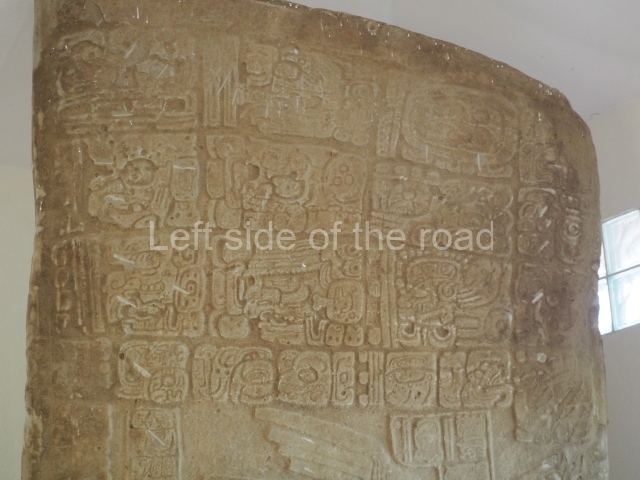

The main group contains 26 monuments – carved in the sandstone and slate found in the geological strata of the Toledo district – although this figure may change if the stela butts are included; these are still embedded in situ and surrounded by the fragments of a few scattered stelae. Seven monuments have reliefs and hieroglyphic inscriptions (stelae 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 14 and 15). No altars or stone slabs have been found, only the smooth ball court marker. The earliest monument, Stela 15, is inscribed with the Long Count date 9.14.10.0.0 (AD 741), while the latest, Stela 3, possibly corresponds to the Maya date 10.0.0.0.0 (AD 830). A distinctive feature of the monuments is their wide range of sculptural styles and formats, each one displaying a different treatment in terms of its inscriptions, apparel and other details. The sculptural tradition lasted approximately four katuns (80 years), but the sculpted monuments reveal great creativity for a centre that was apparently secondary in the hierarchy of settlements in southern Belize; besides, the site even has its own emblem glyph. Uxbenka, a smaller site, and Lubaantun, larger than Nim Li Punit, as well as other sites in the region formed the sociopolitical mosaic towards the end of the Classic era. The sudden emergence of small polities seeking to legitimise their ruling elites gave rise to instability and political fragmentation in the southern area of the Maya lowlands.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp254-256.

How to get there:

From Punta Gorda. The Belize bound bus leaves the centre of Punta Gorda at 08.00 and 10.00 (there are later departures but these are the best for visiting the site). The road leading to the site is on the north-eastern edge of the settlement of Indian Creek – about an hour from Punta Gorda. Bus fare B$5. The site is about 800m metres up a steepish hill from the main road. You might have a long wait to get back as the bus from Belize passes at around 11.30 and 12.30.

GPS:

16d 19’ 16” N

88d 49’ 27” W

Entrance:

B$10