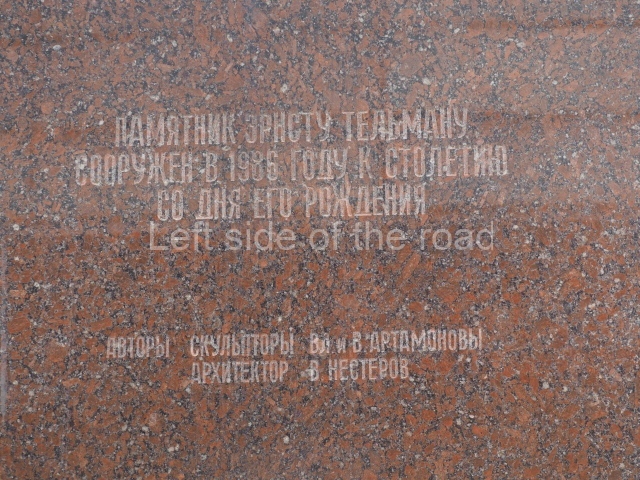

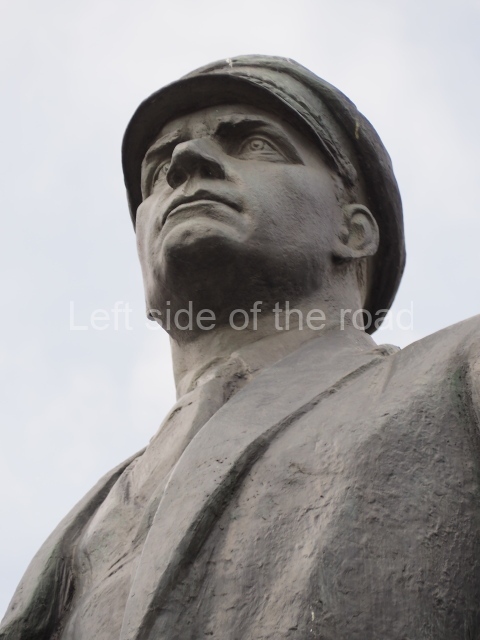

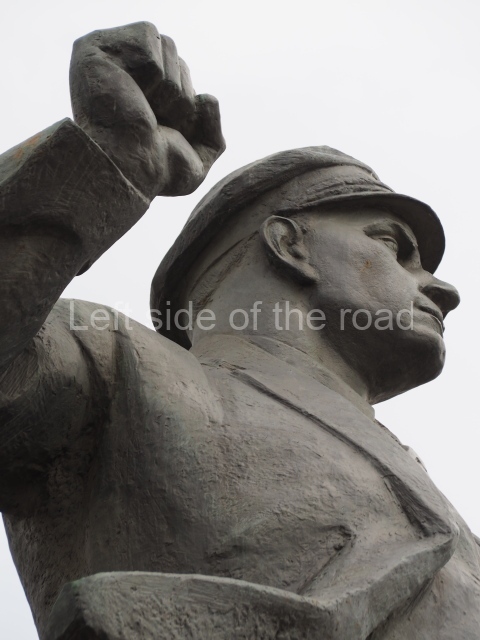

Ernst Thaelmann – German Communist leader – statue in Moscow

It’s difficult to work out the thinking in the early days after the collapse of the (then Revisionist) Soviet Union in 1991 when it comes to revolutionary monuments. They display an element of schizophrenia, not knowing how to deal with the Soviet, Socialist past. But if you take something away with what are you going to replace it? Prior to the October Revolution of 1917 Russia was a backward, undeveloped, country with a population in the countryside that had barely moved from serfdom. The working class was small – yet highly organised and with a political understanding far exceeding that of their companions in the countries of the ‘west’ – and militarily it was of no consequence.

It was the construction of Socialism from 1917 to 1953 that built the country that turned the Soviet Union from a backward, peasant dominated country to an industrialised country with a sophisticated infrastructure and, after the re-construction following the Great Patriotic War, one of the most powerful nations on earth. And, of course, it was the Soviet Union that played the pivotal role in the defeat of Nazism.

So going back to the ‘pre-revolutionary’ period for imagery and options wasn’t really an option so, at least initially. As time moved on the defeat of the Napoleonic imperialist invasion was promoted to greater importance and the iconography of the Orthodox Church appeared in more public spaces.

Statues and other representations of JV Stalin had been removed in the 1950s after Khrushchev’s denunciation at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. This culminated in the removal of his body from the mausoleum he had shared with VI Lenin, for more than seven years, in October 1961. But even then this removal was carried out in the dead of night and at a time when the announcement could have been ‘buried’ by news of a successful nuclear test. However, such a radical move with the body of Lenin, the new capitalists feared, would almost certainly have been met with substantial public opposition.

Nonetheless, there are still images of, or references to, Stalin in public places in Moscow, such as; the roundel which depicts both VI Lenin and JV Stalin in the external decoration of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic pavilion at the Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy (VDNKh); a young woman carries a copy of Stalin’s written works at the Kievskaya, Line 3, Metro station; and he also appears on a bas relief on the platform of Ploschad Vosstaniya Metro station in Leningrad.

There have been continued suggestions about the removal/destruction of the Lenin mausoleum (as was the fate of Georgi Dimitrov in Sofia, Bulgaria) but I would think that such discussions will get nowhere the longer the structure remains in its prominent location in Red Square.

In the early days of the collapse of the Soviet Union, when confusion reigned and any remaining Communist organisation was less than functional, a number of statues and monuments were either removed or destroyed with some of those that were taken down later re-appearing at the Muzeon Art Park.

At the same time there are still almost a hundred statues of VI Lenin in the Greater Moscow area, mostly in local communities but only a handful in the city centre (including the sculptural assembly in Oktyabrskaya Square); Karl Marx still gives a speech just across the road from the Bolshoi Theatre; Frederick Engels stands in a small square near the rebuilt Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, across the road from the ornate entrance to Kropotkinskaya metro station; and there’s a somewhat strange monument to Uncle Ho (Ho Chi Minh) close to the entrance to Akademicheskaya metro station south of the city centre.

And then there’s the statue to Ernst Thaelmann, the German Communist Party leader who was imprisoned by the Nazis and eventually murdered in their custody.

Fifty years old by Wilhelm Pieck

Ernst Thaelmann will be fifty years old on the sixteen of April. There is hardly a corner of the world where the name of the imprisoned leader of the Communist Party of Germany is not uttered with warmth and emotion by all workers and friends of peace and liberty and where his release is not insistently demanded. Ernst Thaelmann, whom the bloodthirsty hangmen of the German proletariat have already kept in prison for three years, whom they are torturing and ill-treating, has become the symbol of the struggle against war and Fascism, the struggle for Socialism, all over the world.

It was a long journey, rich in sacrifice and struggle, that the Hamburg docker, Ernst Thaelmann, had to make before he grew to be the great leader of the producing masses of Germany and one of the most popular leaders of the Communist International.

As the son of a class-conscious worker organised in the Social-Democratic Party, Ernst Thaelmann came into the Socialist movement in his early youth. He was hardly sixteen years old when he joined the Social-Democratic Party. The indigent circumstances of a proletarian family drove him very early into the drudgery of capitalist exploitation. These circumstances prevented him from following the well-meant advice of his teachers that this talented working-class boy should continue his education.

Ernst Thaelmann began his independent proletarian existence as a porter in the Hamburg docks. He made a trip to America as a coal trimmer, and worked as a daily labourer on American farms. Thus the international character of capitalist exploitation was hammered into him in early youth – but at the same time it taught him militant life of the international working class. Arriving back in Hamburg, he devoted his whole energy and all his spare time to work in party and trade union. After a heavy day’s work and an evening spent in the service of the organisation, he voraciously read and studied the Socialist literature. At first his activities were mainly in the trade union field. Very soon his work for the organisation, his personal courage, his self-sacrifice and the successful way in which he stood up for the workers’ demands, won him the confidence of the workers. They elected him to the local executive of their trade union, they sent him four times as delegate to the congress of the Transport Workers’ Union. And already in those days Ernst Thaelmann began his open and determined fight against opportunism.

In Hamburg, Germany’s largest city serving international trade, all the shady sides of the capitalist system were in evidence in their most blatant forms. Besides the strata of labor aristocrats corrupted by colonial surplus profits, it was the circumstance that Hamburg was the seat of a number of central trade union and co-operative institutions with their large bureaucratic apparatus which, more than anything, supplied a firm foundation for opportunism. Among other things it is also noteworthy that after the Revolution of 1918 these opportunist elements in Hamburg became the representatives of the most reactionary and right-wing opinions in Social Democracy. In order to indicate their attitude, it is enough to mention that it was one of the leaders of reactionary Hamburg Social-Democracy (Sarendorff) who replied to the united front proposals of the Communists before Hitler’s assumption to power with the provocative statement that he would ten times rather go with the bourgeoisie than once with the Communists.

In the struggle with these reactionary elements in the working-class movement Ernst Thaelmann became an uncompromising fighter for revolutionary Marxism.

When the slaughter of the nations began, and opportunism went over with banners flying to the camp of chauvinism and imperialism, the revolutionary worker, Ernst Thaelmann, did not waver one minute. From the very first days he fought resolutely against the war policy of Social-Democracy. In the first few weeks of the war he was ordered to the front. As an internationalist he set out to enlighten the troops, circulating illegal leaflets and newspapers and making a stand against the brutal treatment of the soldiers by Prussian militarism. For this he was deliberately victimised by the officers and given the most dangerous duties in the front line. Even from the trenches he kept in close touch with the illegally operating Hamburg opposition. Together with it he joined the Independent Social-Democratic Party. After the outbreak of the Revolution in November 1918, Ernst Thaelmann fought in the foremost ranks of the revolutionary workers against the counter-revolutionary troops which Ebert and Noske had sent to crush the workers of Hamburg and Bremen. The revolutionary workers of Hamburg, who recognised Thaelmann’s personal courage and daring, elected him to represent them in the City government of the port. It was due to him that out of the 42,000 members of the Independent Social-Democratic Party’s organisation in Hamburg, 40,000 declared their allegiance to the principles of the Communist International.

After the Party, following the defeat of the German proletariat in 1923, had devastatingly settled the opportunists, Ernst Thaelmann, as one of the most popular left-wing leaders, was summoned to the Central Committee of the Party, where he very soon rose to be leader of the Party. Under his leadership, the Party quickly and definitely rid itself of the ultra-left group of Ruth Fischer and Maslow, whose pseudo-radical, fatal policy had done immense harm to the mass-influence of the Party, threatening to isolate the Party from the masses.

With the help of the Communist International, he welded all the healthy and valuable forces of the Party in the leadership and in the organisation as a whole into an iron phalanx, which first flung the Trotskyist gang out of the ranks of the Party, only later to cleanse it with equal thoroughness of the Right opportunist and conciliators.

To all of us in the leadership, and to every single Party comrade, Thaelmann became a model revolutionary loyalty and devotion to the Communist International, the World Party of Lenin and Stalin. He taught us absolute devotion and passionate love for the Soviet Union and for our great leader Stalin. Thaelmann never wavered on this question. At the October Conference of the C.P.G. in 1932, he addressed the following words of warning to the Party:

‘There were sometimes in our own ranks comrades who thought themselves cleverer and more capable of judging various questions than was done in the definite decisions of our World Party. Here I stress with the greatest emphasis: our relations with the Comintern, this close, indestructible, firm confidence between the C.P.G. and the C.I. and its Executive – this is one of our Party, the inner-political struggles and disputes in the past and of the higher political maturity of our Party generally.’

The latest war-provocation by German Fascism recalls to our mind Thaelmann’s passionate struggle against war, against Fascism, for an international understanding among the nations, particularly between the working masses of Germany and France. Under Thaelmann’s leadership the Communist Party of Germany resolutely took over and resolutely continued the militant policy of the Spartakus-Bund against the Treaty of Versailles. In contrast to the criminal war-policy of the German-Fascists, however, the policy of the Communist Party is founded on international solidarity among the nations, on peaceful understanding between them, on the alliance of the working class of the whole world. This attitude was forcibly expressed by Thaelmann at that historic mass meeting of the French workers in Paris, at which he had to appear illegally because the French police tried to prevent him from attending. There Thaelmann said:

‘Even more boldly and more courageously we shall hold out our hands over frontier barriers to our militant comrades in France, joining with them in fraternal solidarity in a fighting alliance against the war-criminals and their accomplices. We shall not allow the German and French workers to be goaded again into mutual fratricide.’

The Bolshevist policy of the Communist Party under Thaelmann’s leadership led to a steady, constant increase in its mass-influence. At the elections to the German Reichstag in November 1932, six million working people voted for the Communist Party of Germany. The Party numbered more than 300,000 members, and it was fulfilling with ever-increasing success its great historic task of preparing the working masses of Germany for the struggle for and winning Socialism.

The development of the Party to a mass-party with a vigorous Bolshevist character was largely due to Ernst Thaelmann. He was more than usually sensitive to the temper of the masses, especially the Social-Democratic workers. For this reason he was accused by the group Nuemann of ‘running behind the S.P.G. Workers’. But Ernst Thaelmann’s work was anything but this. Quite the reverse: he tried to make the Social-Democratic workers realise the necessity of the united front in view of the rising wave of Fascism. He tried also, however, to create the conditions for this in the Party itself. At the meeting of the Central Committee on February 19, 1932, he said:

‘We say that the revolutionary united-front policy forms the main link in the proletarian policy in Germany. Comrades, a formulation like this is one of great moment; we have chosen it on mature reflection.’

And at the Berlin Anti-Fascist Unity Congress on July 10, 1932, Thaelmann said: ‘The question of the united front against Fascism … that is the question vital to the German proletariat.’ On the initiative of Ernst Thaelmann the ‘Anti-Fascist Action’ was inaugurated by the Communist Party in May, 1932, bringing the Communist and Social-Democratic workers closer together. And yet there were still present in the Party very powerful sectarian inhibitions among Communist workers against the united front with the Social-Democratic workers, chiefly caused by the struggle conducted against the Communist Party by the Social-Democratic leaders, especially the Social-Democratic Prussian Government, with the use of terrorist methods.

In these circumstances a number of grave errors were made by the Party, to correct which, on the strength of experience gained in the meantime, Ernst Thaelmann would naturally have acted with the utmost vigour if he had not been prevented from doing so by his arrest. The most serious error was that the Fascist menace was under-estimated and the main blow was not aimed at the Fascist menace as it became more and more clearly manifested.

On the bold initiative of Comrade Dimitrov, the Seventh World Congress decided to divert our tactics to the creation of the united front and the People’s Front, and set the Communist Party of Germany, in view of the altered situation in Germany, the special task of revising its relations with Social-Democracy, so that the rapid creation of the united front should become possible.

The working masses in town and country are beginning to revolt against their Fascist oppressors, although under the severe terror this result takes at first the simplest forms. The tasks facing the Communist Party of Germany in such a situation are great and fraught with responsibility. Now is the time, in spite of Fascist rule to terror and the suppression of all free expression of opinion in Germany, to counteract the mass chauvinist infection and to rally all available forces for the overthrow of this mad rule of the war-mongers, the oppressors and murderers of the working people of Germany. It is necessary to unite quickly and boldly all the opponents of the Fascists rule of terror against all reactionary attempts at sabotage and against all sectarian inhibitions; but above all to heal the split in the working class and to lead the Communist and Social-Democratic workers together into a united fighting front.

The C.P.G. lives on and is working despite the tremendous sacrifices it has to make under the Fascist terror. The heroic struggle, full of sacrifices, which tens of thousand of Communists and revolutionary workers are waging at the cost of the lives of thousands of their best, has shown that the Fascist terror and the reformist policy of capitulation were not able to demoralise the ranks of the proletariat. The fact that the Communist Party has been successful in this is due primarily to the heroic cadres raised by the Party under Thaelmann’s leadership.

For more than three years Thaelmann has been lying in a Fascist gaol. During all this time it has only been possible once – through the workers’ delegation from the Saar – for the proletariat to establish personal contact with Thaelmann. The Fascists allow the visit on that occasion in order to confuse the workers of the Saar, because they thought that the long period of terrorism in prison would have cowed Thaelmann and that he would not dare to speak openly to the workers. But Ernst Thaelmann bade farewell to the workers in these words: ‘I have been and I am being tortured! Greet the workers of the Saar from me as I would greet them!’ With that he showed that the brutalities of Fascist imprisonment could not break his revolutionary fortitude.

The indictment against Thaelmann published the other day is no more than a miserable declaration of bankruptcy of the part of the Fascist prosecution. That explains why the Fascists for three whole years have been continually postponing the trial and now want to abandon it all together. The latest report concerning Thaelmann’s fate should arouse the international proletariat the utmost vigilance. Thaelmann has been transferred from the custody of the remand authorities to that of the terrorist Gestapo gangs. This increases the mortal danger in which he is. But, on the other hand, in view of the publication of the indictment against Thaelmaan, the present moment is also favourable for the struggle for his release. If we succeeded in raising a tremendous storm of protest throughout the world, it will be possible to break down the prison walls and as in the case of Dimitrov, deliver Thaelmann from the clutches of the Fascist hangmen. The fact that Ernst Thaelmann has got to spend his fiftieth birthday in the gaols of Hitler-Fascism is an urgent reminder to all the anti-Fascists of the whole world that they must intensify to the utmost their campaign for the release of Thaelmann and the many thousands of imprisoned victims of the White Terror.

We greet Ernst Thaelmann on his fiftieth birthday! Freedom for him and for all anti-Fascists! Long live international solidarity! Long live the joint struggle of the workers of the entire world under the leadership of our great Stalin for peace and liberty for World Communism!

Originally published in The Communist Review, Vol. 3 No. 7, July 1936, pp.12–17, of the Communist Party of Australia. Reproduced in the Marxist Internet Archive.

Ernst Thälmann

April 16, 1886 – August 18, 1944

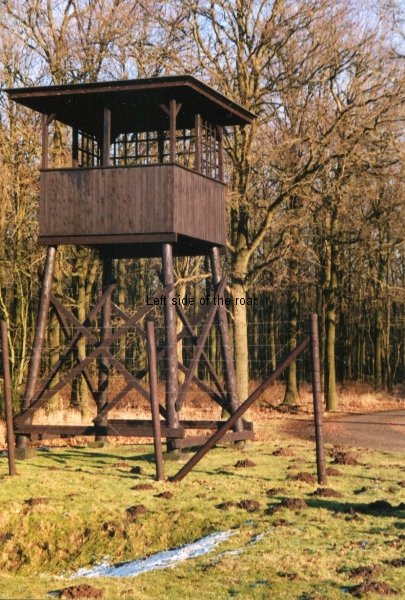

The Hamburg harbour worker Ernst Thälmann was a Social Democrat and organized in the transport workers’ association from 1904. Drafted as a reservist in January 1915, he experienced the horrors of war on the Western Front. In the fall of 1918, he did not return to the troops from leave in Hamburg, remaining in the city until the revolution. He joined the USPD and was elected onto Hamburg’s city parliament in 1919. Along with the majority of the Hamburg USPD, he was in favour of joining the Communist International in 1920 and was a delegate at the party conference in Halle in October of that year. From 1921 he was chairman of the Hamburg KPD district and a member of the party committee for the Wasserkante region. A popular figure in Hamburg, Thälmann was employed as a party secretary there from 1921 and was an uninterrupted member of the city parliament until 1933. He was on the KPD’s central committee from 1921 on and was elected into the party’s leadership at the IXth party conference in Frankfurt in 1924, remaining a member from then on. Representing the party in the Reichstag from 1924 to 1933, he was the KPD’s candidate for the Reich presidential elections in 1925 and 1932. Arrested on March 3, 1933, he remained determined in prison. Thälmann spent twelve years in solitary confinement, first in Moabit, then in Hannover and Bautzen. After being transferred to Buchenwald concentration camp, Ernst Thälmann was murdered on August 18, 1944.

Reproduced from the German Resistance Memorial Centre website.

Related – other statues of revolutionaries in Moscow

Park of the Fallen/Muzeon Art Park

VI Lenin

Location of statue;

At the entrance to the Aeroport Metro station on Line 2, (the dark green one), Khoroshyovsky District, Moscow.

GPS;

55.8003°N

37.5329°E