Comalcalco

More on the Maya

Comalcalco – Tabasco

Location

This site is situated north of the city of Comalcalco, in the state of Tabasco, on the country road leading to the village of Independencia.

History of the explorations

The site was first reported by the French explorer Desire Charnay in 1880. Many of his impressions were based on the descriptions provided by Carl Berendt, who visited Comalcalco and other sites in the region in 1869. Frans Blom and Oliver la Farge described the site again in 1925 following explorations funded by Tulane University. They drew up a provisional map and their impressions of Comalcalco can be found in the hook Tribus y Templos, obligatory reading for anyone Interested in the archaeology of the Maya lowlands and the Usumacinta Basin. The first archaeological Intervention was carried out by Gordon Ekholm in 1956-57 and was funded by the American Museum of Natural History. The researchers were particularly surprised by the use of brick as a building material and their discovery of bricks with inscriptions and graffiti. In 1960, the INAH embarked on a series of archaeological explorations that have continued to this day. That year, Roman Pina Chan led the excavations In the Great Acropolis and consolidated several of the more poorly preserved buildings. From 1972 to 1982, the archaeologist Ponciano Salazar directed the excavations and building consolidation, providing us with the knowledge we have today of the city’s architecture and timeline. In the last five years, Ricardo Armijo and the INAH have conducted more detailed excavations in the areas already explored, placing great importance on the use of the rich epigraphic corpus to understand the history of the site and its archaeological significance.

Pre-Hispanic history

Comalcalco has benefited from the rapid development of Maya epigraphy in recent years, as evidenced by the fact that we now know much more about the genealogy of rulers. Although this does not correspond entirely to the long period of occupation, it does shed light on court life at the site during the 6th, 7th and 8th centuries. We also know that that the pre-Hispanic name for Comalcalco was Joy Chan, and that in AD 649 the city was defeated in battle by Bahlam Ahaw, the ruler of Tortuguero, an important site mid-way between Comalcalco and Palenque. Our knowledge also extends to certain aspects of the lives of eight successive rulers, commencing with Chan Tok’ I in the 6th century and terminating with the reign of El-Kinich (Burnt Sun) at the end of the 8th century.

Site description

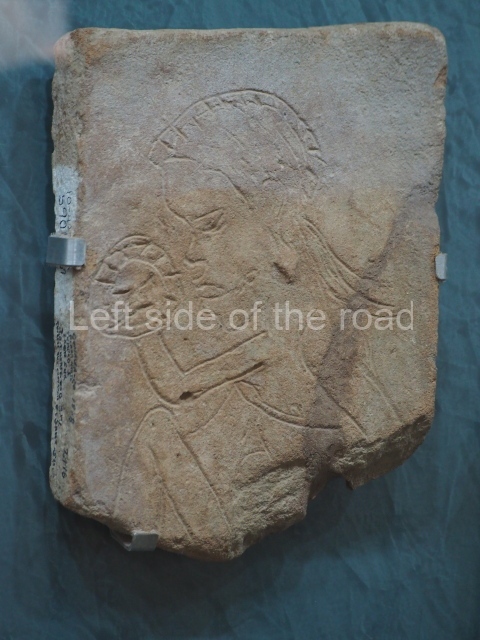

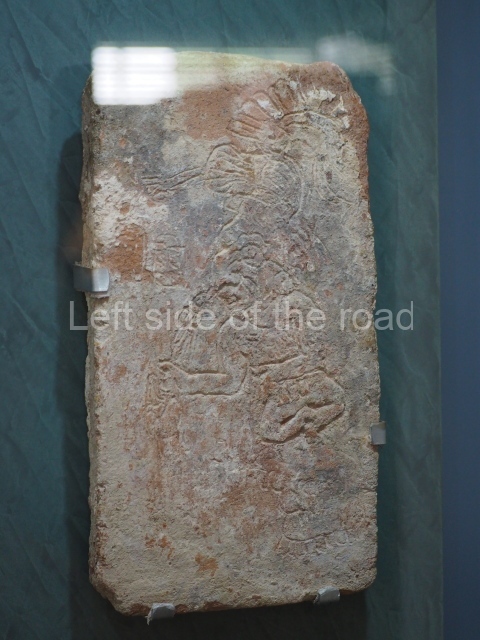

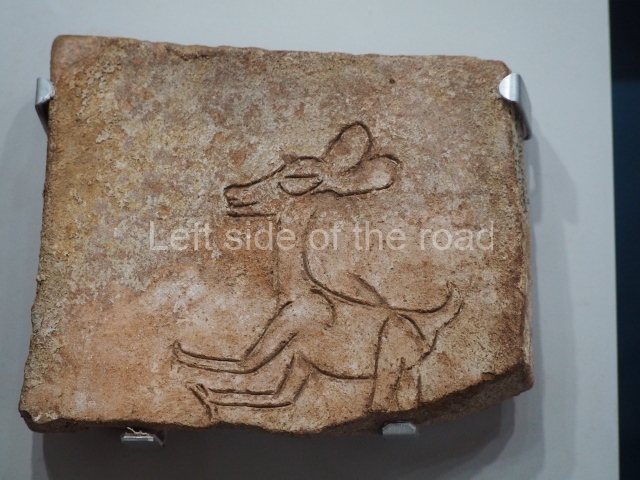

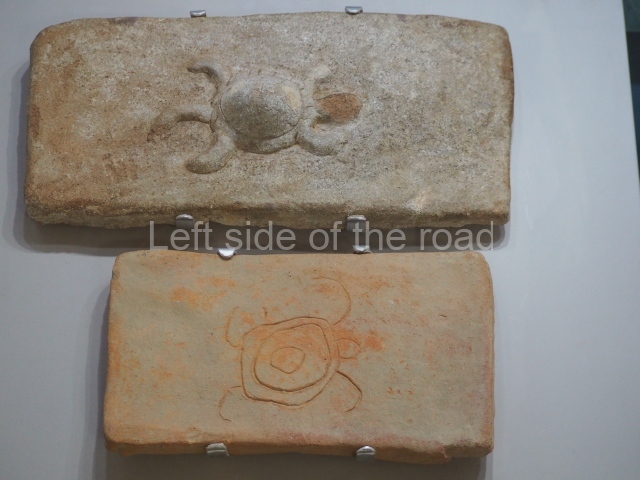

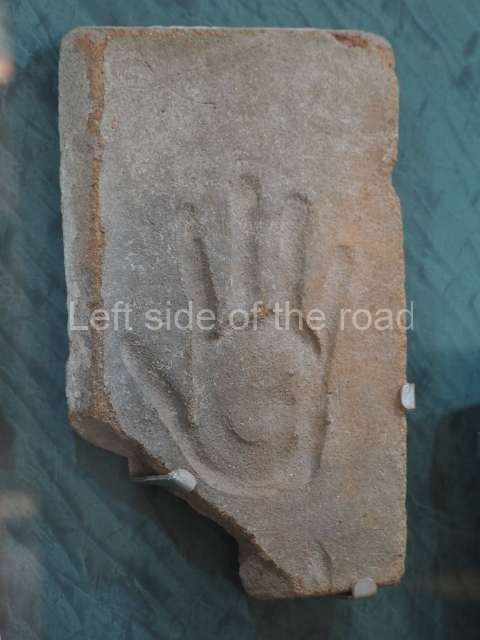

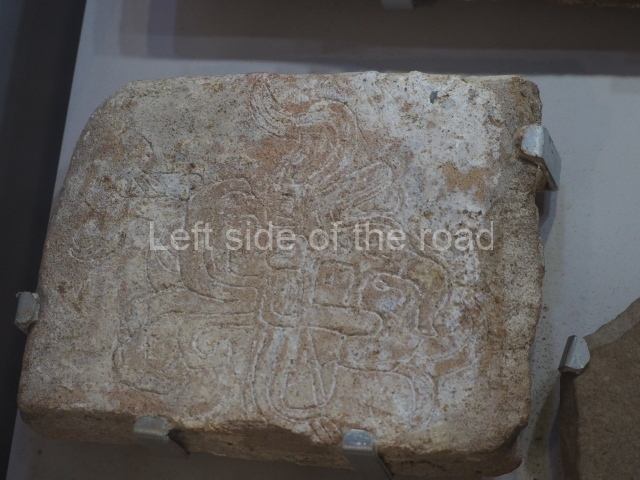

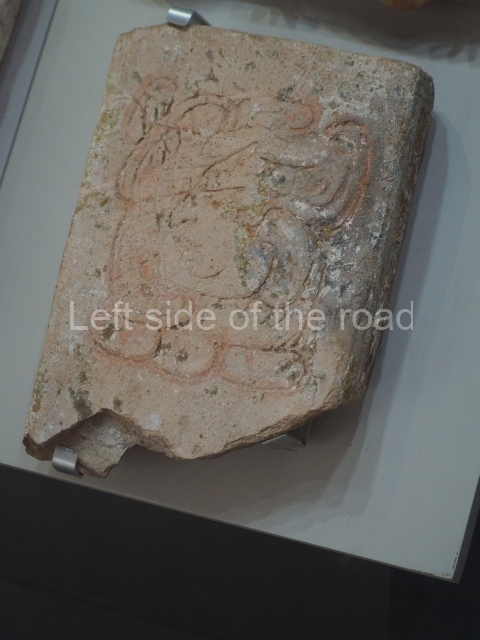

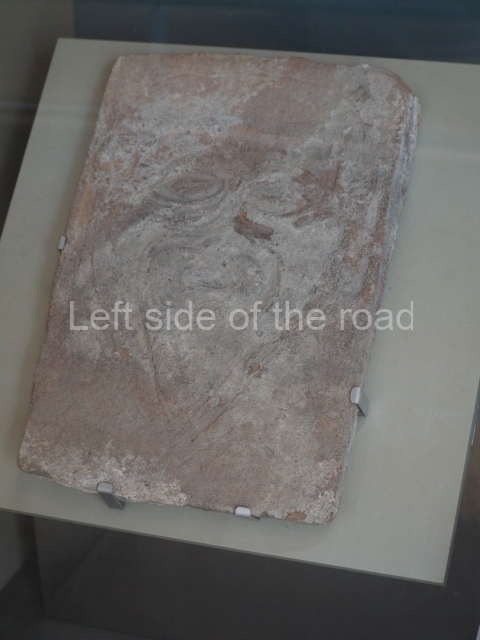

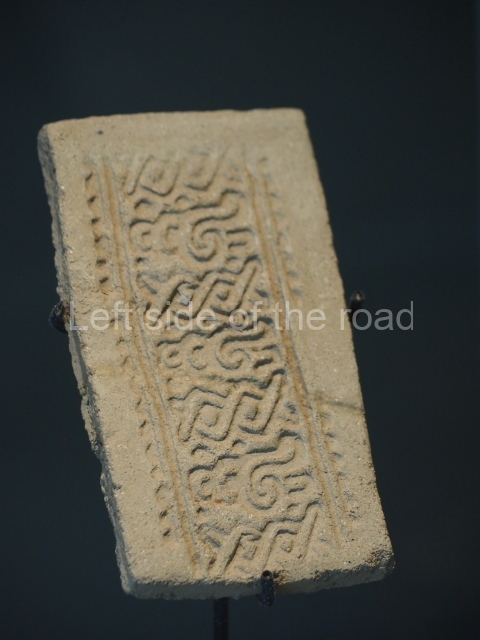

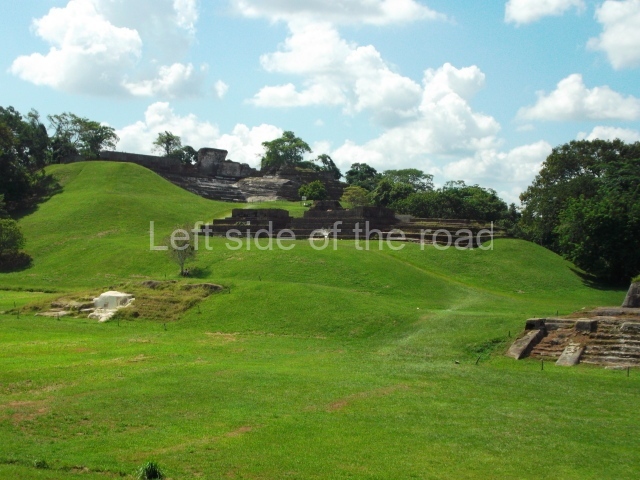

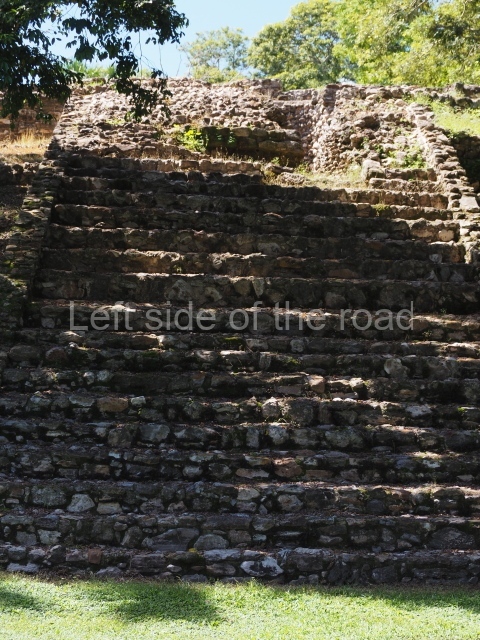

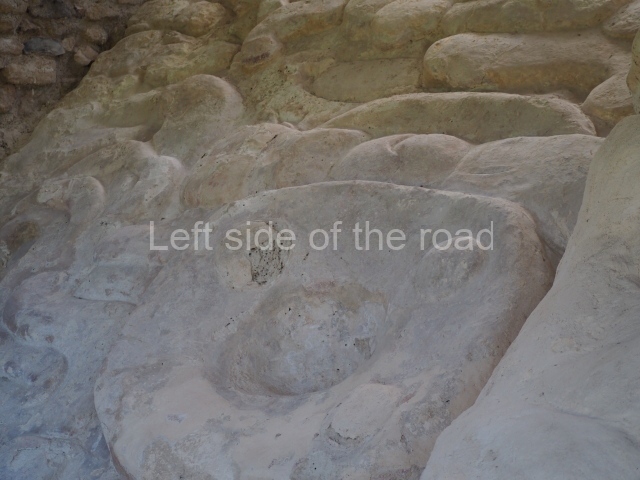

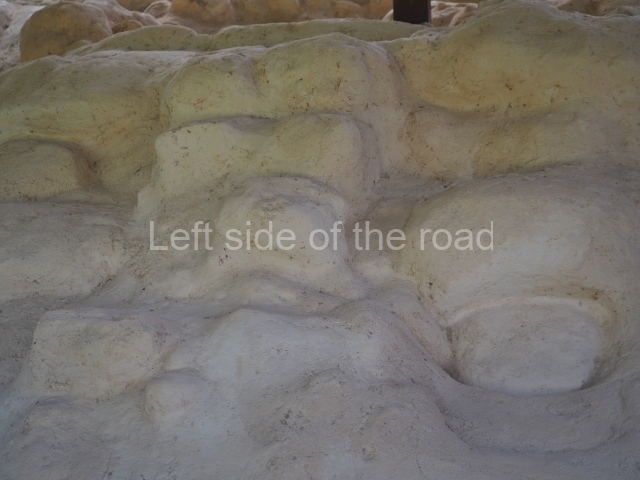

The city is situated on slightly elevated ground with panoramic views of the alluvial plain, very close to the River Mazapa-Dos Bocas, also known as the River Seco (‘dry’). The size of the city is subject to debate. It would appear to have been more dispersed and less populated than Palenque. Altogether, 432 buildings have been recorded, distributed between three Architectural groups: the North Plaza, the Great Acropolis and the East Acropolis. The city’s original name, furnished by the phonetic interpretation of its emblem glyph, is Joy Chan (Surrounded Sky). Although it was developed over a long period, from the middle of the Preclassic to the Terminal Classic, the Introduction of bricks for the buildings in the North Plaza and the Great Acropolis dates from AD 500. Excavations have yielded a brick with the calendric date of 10 August 561, which is probably when construction of the Great Acropolis commenced. Between the 1st century BC and the 6th century AD, the buildings were made of rammed earth and then covered with stucco, while the temples, situated on weak pyramids, were wattle-and-daub constructions complemented with tree trunks and roofs of palm or guano. In the 7th century AD, the lack of stone obliged the Maya to build their monuments out of fired bricks. Comalcalco is also noted for the elongated buildings with parallel bays on tiered sloping platforms, very like the ones to be found at Palenque. The fact that these buildings are so well preserved today is owing to their excellent mortar, masonry, fine execution, drainage systems based on fitted fired-clay pipes, and a skilful spatial layout. Another characteristic of Comalcalco is the use of a variety of techniques. There are buildings made out of rammed earth and others made out of adobe bricks. Meanwhile, the building facades were covered with a lime stucco and then a thick coat of paint. They used perishable materials such as guano, lianas and wood to build roofs and cover the walls of both public and domestic buildings. The mortar, principally obtained from ground oyster shells rather than the lime obtained from ground limestone, as at Palenque, served as a binder for the clay bricks. The main buildings were covered with decorations modelled in the round, representing a great variety of themes: richly garbed dignitaries, mythological creatures, glyphs and natural motifs.

North plaza.

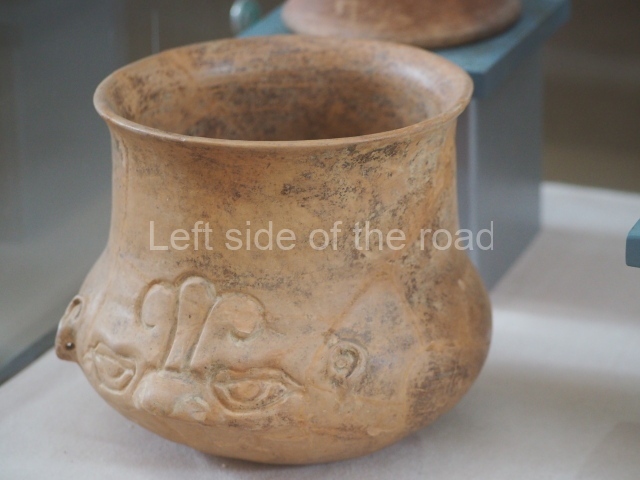

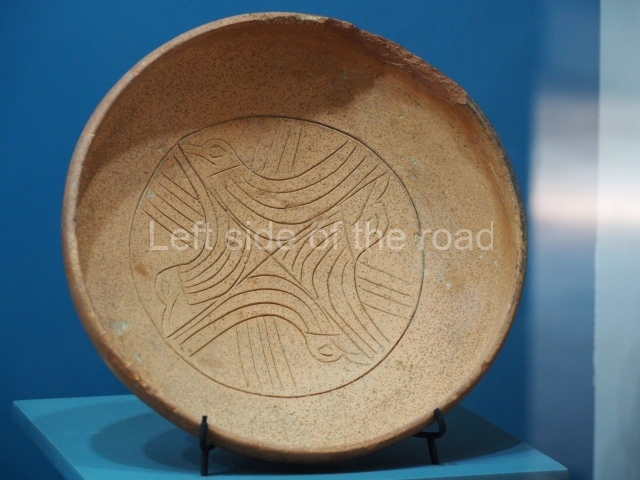

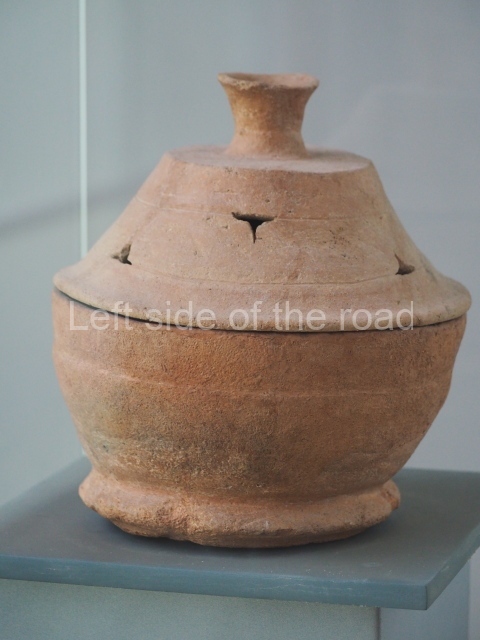

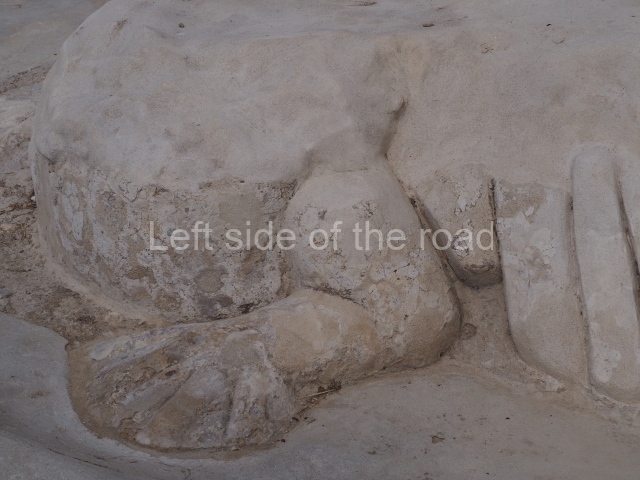

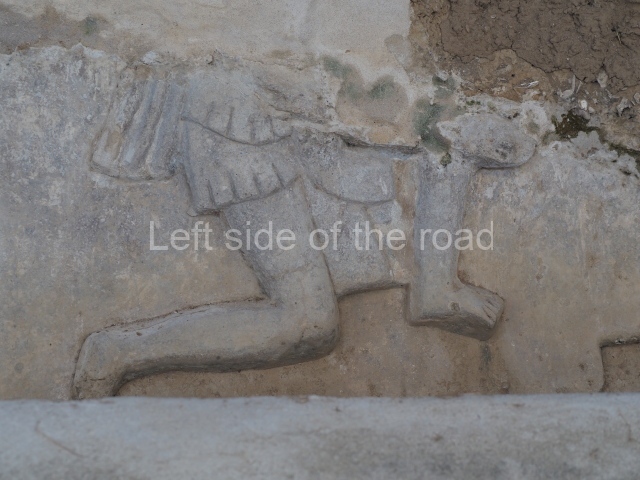

This group displays a simple, axial arrangement. The constructions surround a large rectangular plaza, with the long side running east-west. The north side of the plaza is delimited by a long platform, at the west end of which once stood Temple I. The south side is delimited by another elongated platform with the remains of Temple III at its west end. Both are modest constructions built out of small bricks and comprising two bays, the front one occupied by the portico and the rear one by the shrine, like the Temples in the Cross Group at Palenque. Temple I is the most important monument in the North Plaza and because of its vast dimensions (standing nearly 25 m tall) the only one on the west side. It consists of a ten-tiered pyramid surmounted by a plinth and temple, the latter reached by the stairway on the facade overlooking the plaza. The first section of the stairway (36 steps) corresponds to the first construction or stucco phase and the remainder to the brick phase. The central part of this space yielded three radial altars aligned in a row. Very little evidence remains of the decoration that once covered the main facade, and only a few stucco models on the first slope of the platform have survived in a recognisable condition. It is possible to discern the figure of a toad accompanied by three dignitaries seated on a band, although only the torso and legs have survived. This same slope or talud also displays an individual pinned down on a bench by another figure, no doubt his captor. Temple I is accessed via a wide ramp or balustraded stairway culminating in a series of narrower steps with a basalt sculpture of a skull. Numerous funerary urns have been discovered in this group. This burial practice has been described in connection with other Maya areas (Guatemalan Highlands, the Balancan region, Tabasco) and at Comalcalco it was used for burying high-ranking dignitaries. The urns are enormous vessels made out of modelled clay and deposited inside buildings. They furnished the remains of shrouded individuals in a sitting position accompanied by a rich offering of ceramic objects, earrings, figurines, shark teeth, jaguar and crocodile bones, tortoise shells, shell earrings and obsidian or flint knives. Of the 31 urns discovered, 23 were found in the North Plaza. The most important offering in terms of the quantity and quality of the objects is Funerary Urn 26, deposited between Temples II and Ha, which contained the incomplete remains of an adult male accompanied by 52 shark teeth, 90 shell earrings and 30 stingray tails. Many of these objects were inscribed with long texts that made reference to important events and dates in the life of Aj Pakal Tahn, a high-ranking dignitary who lived at Comalcalco between AD 765 and 777.

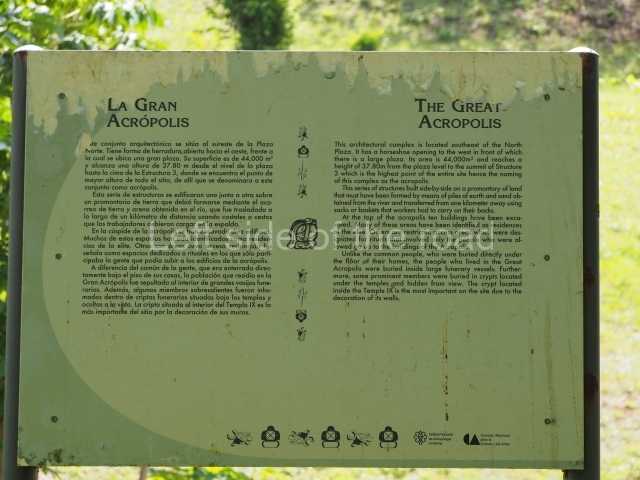

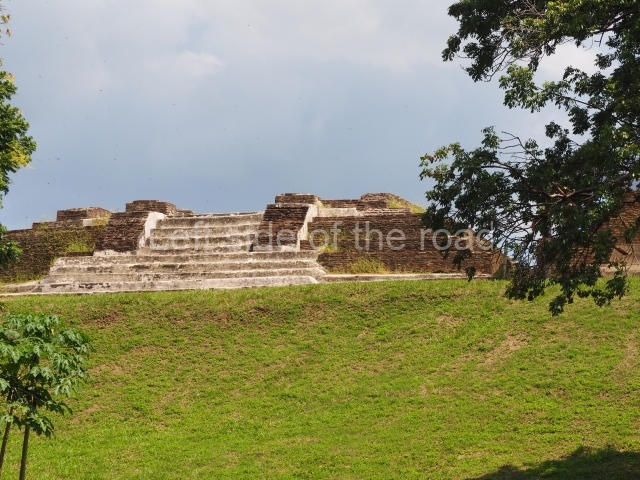

Great Acropolis.

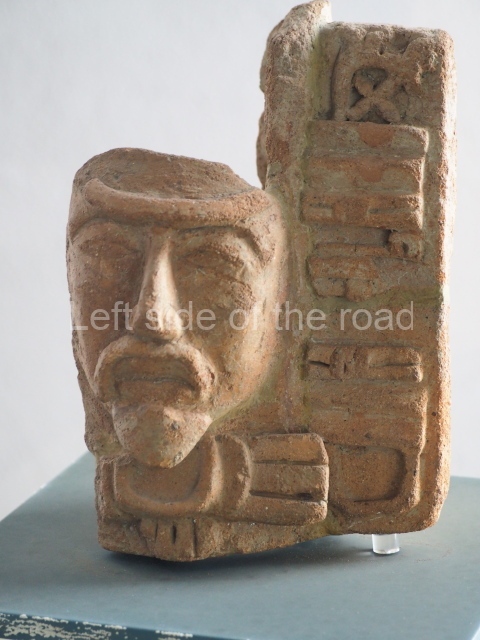

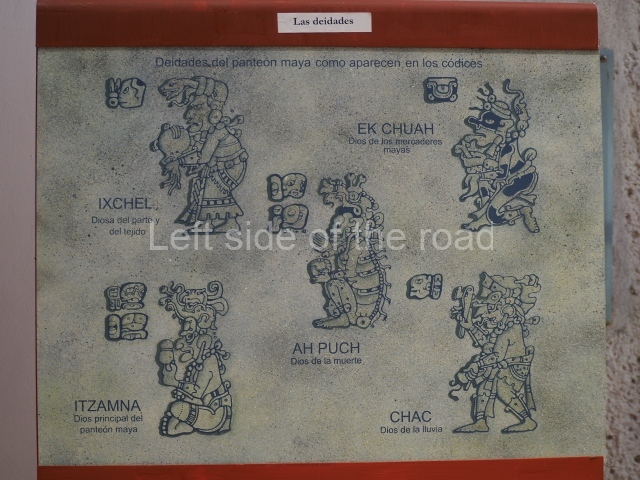

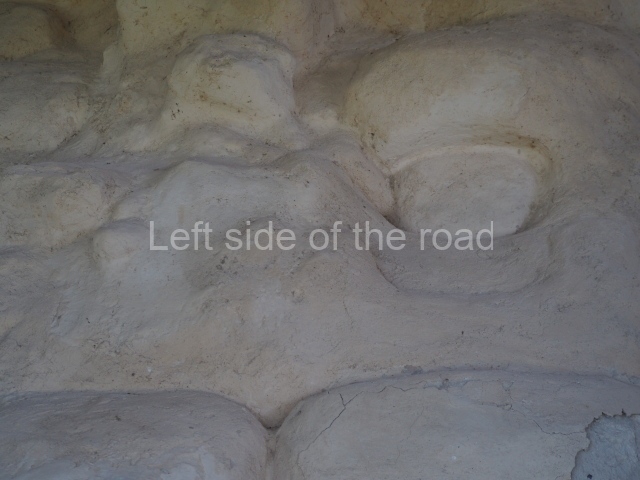

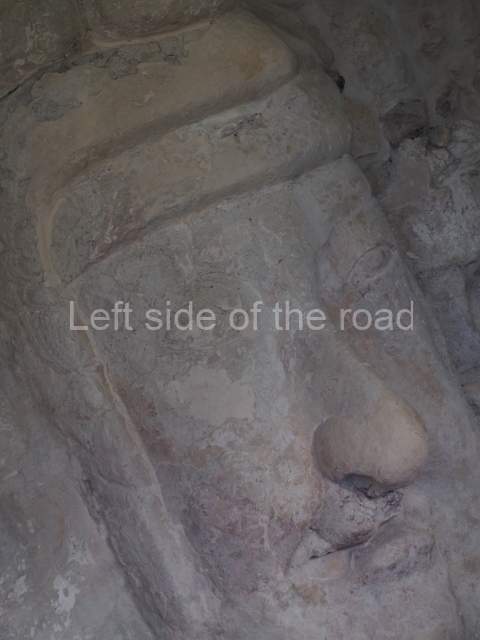

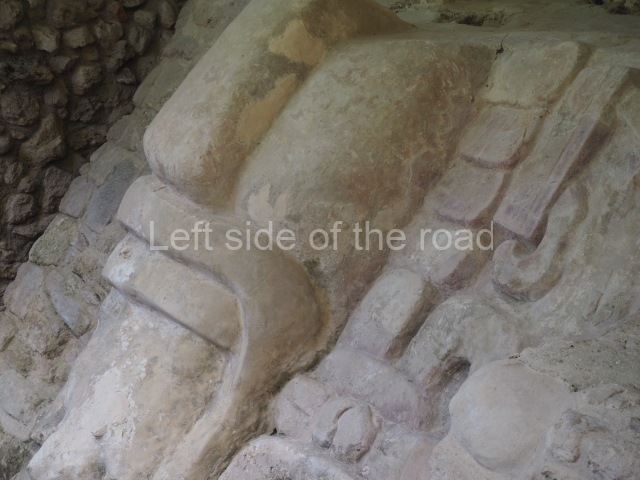

This is the largest architectural group in the city, covering a surface area of 43,878 sq m and standing 39 m tall. It comprises several buildings on different levels and the main entrance is situated on the west side. Three funerary buildings, a palace, two temples and four residential units have been excavated. The excavations at temples VI and VII reveal a short occupation sequence and two construction phases. This is not representative of the group overall because the Acropolis has ceramic remains from a much earlier date. Visible on the main facade of Temple VI is a stucco sculpture of one of the principal deities in the Maya pantheon, Itzamnaaj, a celestial deity identified by his front band decorated with flowers and his curved nose. The three buildings that have been excavated are tiered platforms with funerary crypts inside them. They are surmounted by double-bay temples with interior shrines. The excavations have shown that the entrance to the funerary crypts was sealed and hidden by stairways. Temple IX (the Tomb of the Stuccoes or the Nine Lords of the Night) still contains the funerary crypt as well as the bases of the temple walls. The crypt walls display the stucco-modelled figures of nine individuals. The remains inside the tomb belong to one of the city’s rulers and the dignitaries in the scene probably represent important members of the court. This tomb is situated south-east of the Palace, on a lower level than the artificial platform, and is regarded as the most important of the three tombs found at Comalcalco. It measures 3×3 m and is approximately 2.8 m tall. Situated in the uppermost section of the Great Acropolis is an architectural group comprising the following constructions:

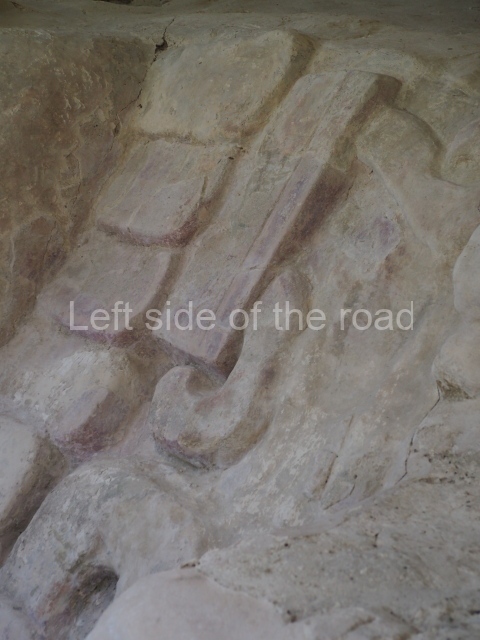

Popol nah or House of the mat.

This contains the remains of stucco-modelled bands which according to Ricardo Armijo represent the ‘royal mat’ or pop, the symbol in Mesoamerican cultures of the political and religious power wielded by the rulers.

Palace.

This imposing structure measures 80×8 m and stands 9 m tall. The largest construction at the Acropolis, it is an excellent example of what are known in the colonial sources of the Guatemalan Highlands as ‘elongated houses’ or nim ha, which served as the rulers’ residences. The facade of this construction is defined by pilasters with stucco-modelled images, reminiscent of Palenque, and it contains two long galleries of rooms along the west and east sides. The galleries are interconnected and roofed with brick corbel vaults covered in stucco, while their walls display the remains of niches or openings. Some of the rooms contain low altars in the fashion of abutted benches;

Sunken Court.

Situated south-east of the Palace at a lower level, this space measures approximately 23×11 m. The north side is delimited by Structure 2, a residential construction of which only the main facade has been explored. Visible today are two pilasters and three entrance openings, as well as the remains of what was probably a dividing wall. The south side of the court is delimited by Temple IV or the Tomb, a platform measuring approximately 18.5×7.50 m and standing 10 m tall. A central stairway leads to a temple at the top of the platform containing two bays, one for the portico or vestibule and the other subdivided into three cells with a shrine in the middle one. Also at the centre of the temple is a tomb whose walls are decorated with stucco figures. Flanking the east side of the court is another platform with a central stairway containing an altar with a hieroglyphic Inscription in the stucco. This construction is situated at an angle to Structure 2 to the south-east, which consists of an altar measuring 2×2 m and standing 0.6 m high, with vertical walls and light moulding. The other buildings that have been excavated in the Great Acropolis are:

Temple V.

Situated west of the south side of the Palace, this north-facing structure is similar to Temple IV. At Its base is a tomb whose entrance was sealed by the stairway.

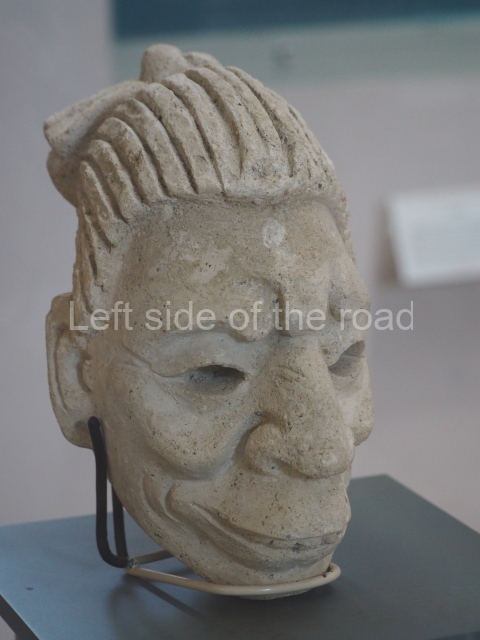

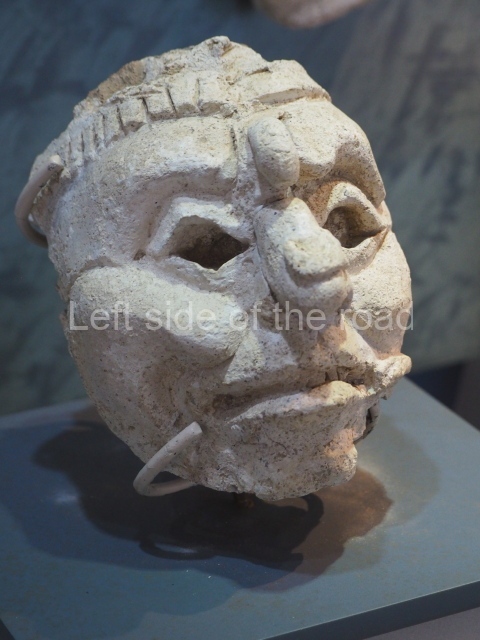

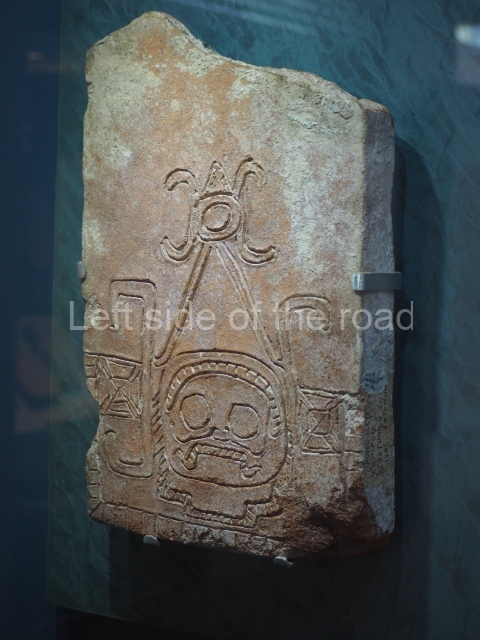

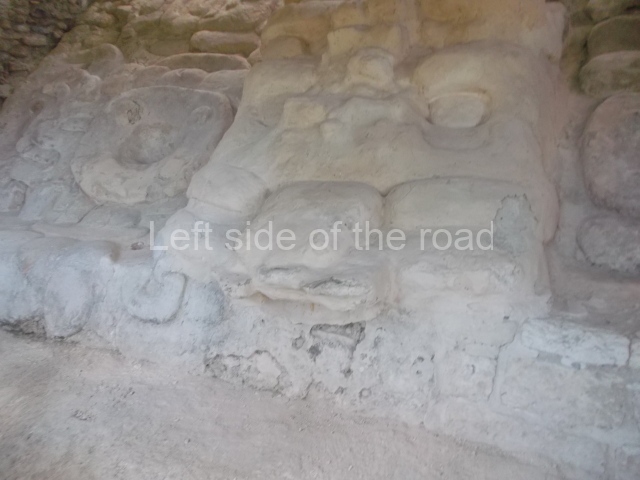

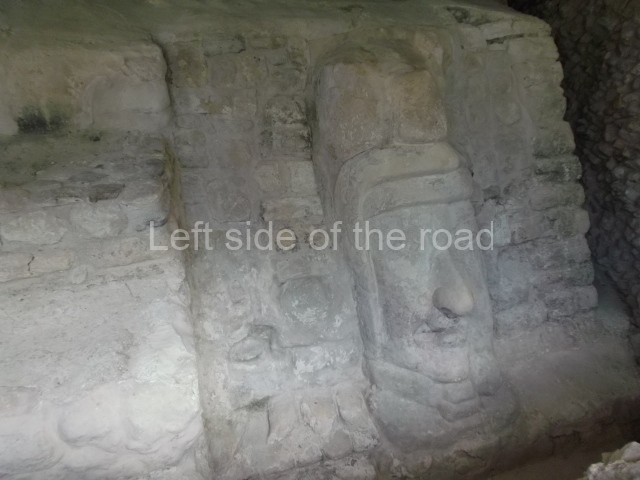

Temple VI or Mask platform.

This elongated monument oriented east-west measures 15×12 m and stands approximately 10.5 m tall. It displays two construction phases, the first characterised by the use of stucco and the second by the use of brick. The south-facing facade corresponds to the first phase and overlooks the Great Acropolis Plaza. It is a three-tier platform with a central stairway flanked by balustrades, also tiered, at the base of which is a handsome stucco mask with the effigy of the sun god. The north, east and west facades belong to the second construction phase, as does the temple at the top of the three-tier pyramid. The temple rests on a low plinth and adopted the same layout as temples IV and V: a portico with three openings formed by pillars and in the rear bay the shrine and two lateral cells. The roof was the typical Maya vault.

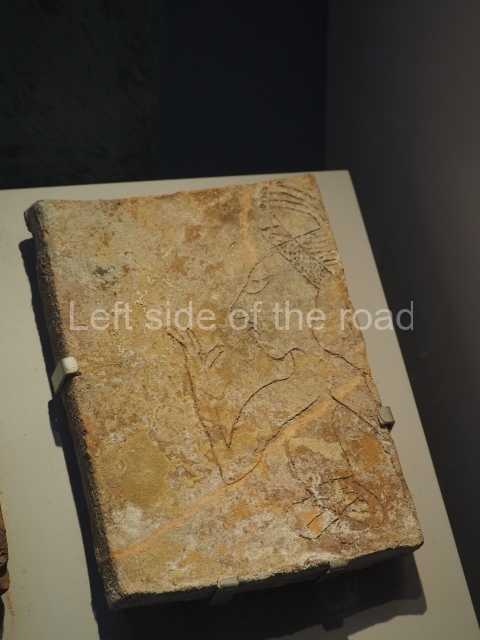

Temple VII or Temple of the seated figures.

This is situated on the west side of Temple VI. Its main facade is south-facing and the first two tiers display various seated figures, as if depositing an offering; the third tier shows a stylised serpent and a band of hieroglyphs. The central stairway, which is flanked by balustrades, led to the temple, the first version of which was made out of wattle-and-daub and the second out of brick. It adopted the typical format of a portico and shrine with lateral cells.

Temple VIII.

This has not been explored but it must have resembled the previous temples as it constituted the third element on the north-west wing of the Great Acropolis.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 131-134.

Comalcalco

1. North Plaza; 2. Temple I; 3. temple II; 4. Temple IV; 5. Temple IIIa; 6. Great Acropolis Plaza; 7. Great Acropolis; 8. Palace; 9. Temple VI; 10. Temple VII; 11. Temple V; 12. Temple IX; 13. Temple IV.

How to get there:

From the town of Colmacalco. Take a bus or combi from the corner of Nicolas Bravo and La Paz, opposite the new structures of the Mercado 27 de Octubre, going in the direction of Paraiso. Get off at the big junction at the end of the long approach (urban) road to the site, less than 3kms from the town.

From Villahermosa. Take a bus or combi that is heading to Paraiso and get off as described above.

GPS:

18d 16’46” N

93d 12’ 04” W

Entrance:

M$75

See also; Comalcalco Site Museum

More on the Maya