More on the ‘Revolutionary Year’

Ukraine – what you’re not told

Independence Day – 29th November – in Gjirokaster

Albania celebrates two ‘independence’ days. The first, on 28th November, is the anniversary of when Albania ‘gained’ its independence from the Ottomans with the signing of an agreement in Vlora in 1912. But this was sham independence (although it was still celebrated during the Socialist period and Enver Hoxha was very much involved in the design of the huge lapidar to commemorate the event which exists in that city) as nothing significantly changed for the vast majority of the population. The second was much more meaningful and that occurred on the 29th November 1944. That was the date when the last of the Nazi invaders of the country were either dead or had surrendered.

There’s very much a political divide when it comes to celebrating these respective dates.

The ‘right’, the reactionaries, will make a big deal out of the 28th as all countries need something to which they can attach their identity. For them the period between 1944 and 1990 was a disaster as the Party of Labour of Albania led the people in the construction of Socialism and that necessarily meant stamping down on private wealth and selfishness. They will, therefore, ‘ignore’ any commemoration of the 29th.

The ‘left’ will probably celebrate both days but the one on the 29th will be of more significance. Much of what was gained in the country following that date in 1944 has now been lost. Even the ‘left’ governments that have been in power since 1990 have merely presided over the restoration of capitalism and all governments have effectively given up any independence the country had, either the 1912 version or the true independence of 1944 – to not even the highest bidder. Anyone, be it the European Union (EU), the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance (NATO), the various brands of mysticism or companies from anywhere in the capitalist world can come in and do whatsoever they like. The only response from the political parties (and, it must be said, the population in general) is ‘please sir, can we have some more?’

But, sadly, neither of these dates seem to be of any importance to the vast majority of the population. Certainly when it comes to attending any formal celebration.

In Gjirokaster, in 2021, the 28th involved a wreath laying ceremony at the lapidar to the Cajupis. These were independence fighters against the Ottomans in the 19th century. Even this innocuous lapidar was submitted to vandal attacks at some time after the victory of the counter-revolution in 1990 but a few years ago it was cleaned up and access to it made much easier so this is why the town now has a rallying point for pre-Socialist celebrations.

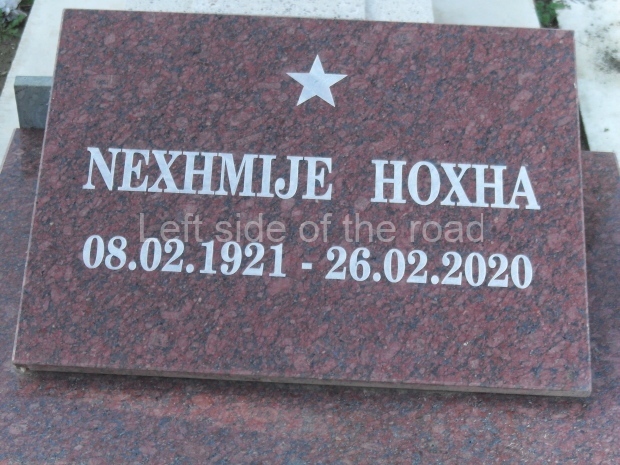

On the other hand the commemoration of the 29th takes place in the Martyrs’ Cemetery, which is on the edge of the new town, close to the north-south main road. This was the place where the commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of the town took place on 18th September 2019.

In 2021 the commemoration was no more than a wreath laying ceremony – so not significantly different from the event the previous day. There were formal wreaths from the local municipality and a number of political parties on the ‘left’ – but nothing from the so-called ‘Democratic Party’, a bunch of fascist inclined individuals who regret that the Nazis lost the battle for Tirana. There were also a couple of individual offerings.

In the past, during the Socialist period, such events would have been crowded and highly organised. The tradition was that members of the Young Pioneers would be standing next to the (empty) tombs and would be charged with laying a single flower on each of them at one point in the ceremony. (Even though these monuments to those who died in the fight against fascism are called ‘cemeteries’ no bodies are interred there, the vast majority of those who died having done so high in the mountains throughout Albania, their remains being lost to nature.)

However, now at such events the individuals who receive a token of respect are only those who still have family members close by and who respect the sacrifice they made. This meant that only a handful of tombs received a floral tribute.

Amongst the ‘tombs’ are two of the young female Partisan fighters, Bule Naipi and Persefoni Kokedhima, who were murdered by the Nazis in a public execution on July 17th 1944, a few short months before the liberation of the town. These young women were 22 and 21 respectively. However, their sacrifice wasn’t remembered in any significant way with only a single flower being laid on Bule’s tomb.

And the ‘commemoration’ was over in less than 15 minutes – about the same time of the event the previous day.

One interesting thing that happened, when most people had left, was that a wreath laid by the local police was removed from the collection of wreaths at the centre of the lapidar and moved so that it stood alone. I assume some sort of political comment but don”t know exactly what.

I assume that such commemorations will take place in other Martyrs’ Cemeteries throughout the country but that could well be dependent upon which political faction controls the local municipality.

More on Albania …..