Librazhd Martyrs Cemetery

More on Albania …..

Librazhd Martyrs’ Cemetery

Like many of its kind in Albania the Librazhd Martyrs’ Cemetery sits on a high location over the town. This is both to give due reverence to those who gave their lives in the National Liberation War as well as to reflect that the war itself was very much one that was won and (for the Fascists) lost in the mountains.

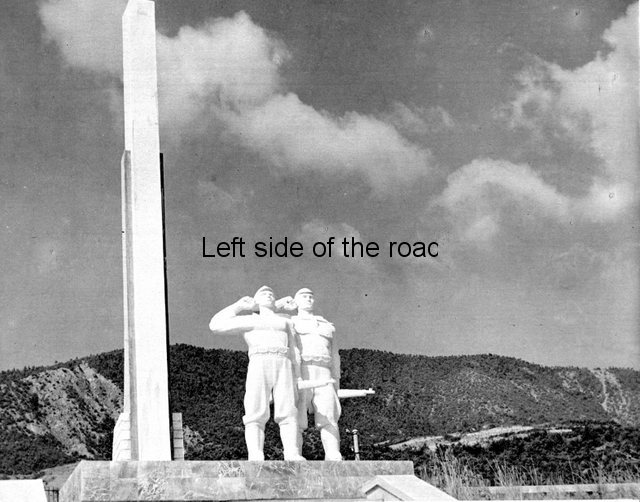

Here the idea was to commemorate the Partisans by installing a statue of two of them, a male and a female, and is the work of M Turkeshi and L Berhami. Although not common this idea was used on a number of occasions throughout the country, for example in Lushnje, Fier and Korça.

They stand close together on a marble faced plinth on a plateau which is reached by a flight of steps from the small road below. The idea of equality is expressed in the very similar manner in which they are presented. Apart from their gender the only significant difference in that presentation is the fact that the women is slightly shorter than the man.

ALS 34 – Librazhd Martyrs Cemetery – 03

The woman is on the left and is in full Communist Partisan uniform. This means that her cap bears a star at the front and she wear a scarf (which would have been red) around her neck. Although not all those who fought against first the Italian and then the German Fascist invaders were Communists a significant number of them were and this is the way to distinguish them in any artistic representation.

Over her chest, running from her right shoulder to her left hip, is a strap and around her waist she has a belt to which are attached ammunition pouches which completely fill the belt, there being more than a dozen – each one containing five bullets, so well prepared for action. Over the shins of her trousers are what looks like puttees and on her feet are a stout pair of shoes.

In a sense this is an idealised depiction of the Partisan uniform. By the end of the war some of the Partisans might have been dressed in such a formal manner but for the majority of the fighters their clothing would have been anything that was available. By its very nature a Partisan army is a guerrilla force and the constant change of circumstances and its role in that war meant that their clothing would reflect those developments.

Also here we have quite an austere, a very simple representation of the uniform. It is functional and has no other ornament nor imperfection. It’s the sort of uniform a fastidious sergeant major in the British imperialist army would be proud, all the creases in the right place.

She looks directly in front of her and her right hand is raised in a clenched fist, Communist salute, her hand touching the right side of her head. Her left arm hangs straight down and she holds her rifle between the firing mechanism and the butt so that it is horizontal and at 90 degrees to her body.

She is standing to attention in respect to her fallen comrades but also, by her preparedness, showing that she is ready for action at any time in the future.

The presence of the female was an important aspect of the statues and monuments created in the 1970s and 80’s. These works of art placed an emphasis on the role of women both in achieving the liberation of the country from the Fascists in the Second World War as well as in the task of building Socialism for a better future. The article by Ramiz Alia, on page 33 of Vol 1 of the Albanian Lapidar Survey, goes into greater detail about the reasoning behind this decision.

Her male comrade is dressed in exactly the same manner, as is his stance, stressing the equality between them.

Behind them is one story building which curves behind the statue in a partial arc. This would have been the local museum to the Partisans but as in the overwhelming number of cases throughout the country these are now abandoned and derelict, and to a greater or lesser state of dereliction – at least here they are abandoned but not used a local rubbish dump.

On the border above the entrance gates to this building are the words ‘Lavdi Desmoreve’ meaning ‘Glory to the Martyrs’. These two words are in red but in a completely different font so I assume that at least one of them is not original. The letters look like they’ve been recently painted but I don’t understand why, if the cemetery is being looked after in a respectful manner, someone hasn’t realised that these two conflicting fonts look very strange.

ALS 34 – Librazhd Martyrs Cemetery – 09

On the plateau that this building creates sits a stone monolith. This is in two parts but sections which are joined together, the one on the right being slightly lower than that on the left. From the point where they join the stones curve away gently to form a pleasing variation on a straightforward monolith. Often such a monolith would have a red star placed at the top but the design of this one would mean that wherever a star was placed it would look in the wrong place.

A monolith is common in Martyrs’ Cemeteries throughout Albania and is both an indicator of the location of the cemetery as well as representing the soaring heights of the sacrifice of those commemorated.

On either side of the structure and the statue stands a palm tree. Palm trees appear in a number of other martyrs’ cemeteries including Lushnje and Elbasan. Over the centuries (and through many cultures) the symbolism of palm trees has come to represent – amongst others – values such as truth, honour, valour, freedom and victory, all which would make them appropriate here. The trees also often grow to be tall, soaring to the sky, just as the monoliths do in the cemeteries.

This is the arrangement now but it hasn’t always been like this. As with many lapidars the one at Librazhd has gone through an evolutionary process. Originally there was just one level and on that stood plaster versions of the existing bronze statues. These are dated to 1971, so some of the earliest statues of Albania’s Cultural Revolution. Close to and just behind the sculpture was a simple, tall monolith.

Librazhd Martyrs’ Cemetery – 1971

At a date of which I am presently unaware there was a decision to rearrange the top of the cemetery and as well as building the museum the statue was cast in bronze.

The tombs of those from Librazhd are in rows in levels below that of the statue and the monolith. In general they are in a good state, as is the whole surrounding area, the only sign of neglect being that of the museum, which has probably now been empty and unused for a couple of decades.

Location:

The hill on which the Martyrs’ Cemetery is located is only a few minutes walk to the north-west of the town and is reached by taking a turn-off to the left from the main road heading towards Përrenjas.

GPS:

41.17833001

20.32066704

DMS:

41° 10′ 41.9880” N

20° 19′ 14.4013” E

Altitude:

299.3 m

In the centre of Librazhd is another lapidar that commemorates the Partisans who operated in the area and who were instrumental in the liberation of town in November 1944. Very recent buildings now surround this lapidar but originally it would have been much more prominent.

20th Brigade – Librazhd

Up a flight of a dozen steps from the road a simple, tall, marble faced monolith is flanked by two concrete panels. On the left hand panel are two large X’s, now painted red. These are the Roman numerals for twenty, symbolising the 20th Brigade that was formed and would have often fought in the Librazhd region. On the right hand panel, inscribed on a rectangular piece of marble, are the names of 32 members of that brigade who died in the war.

The first, Qibra Sokoli, has the word ‘heroine’ written beside it, this means that she is officially considered a ‘People’s Heroine’, someone who went that extra distance and died as a consequence in the war against the Fascist invaders. (The more I write about Albanian lapidars the more I feel that this hierarchy in death is somewhat unnecessary. Surely ALL those who died, in whatever circumstances, as part of the partisan army are ‘People’s Heroes/Heroines’?)

Qibra Sokoli – 1924-1944

Qibra (sometimes written Qybra) was born (1924) in Korça, a town to the south-east of Librazhd. Her father was killed by collaborators in 1942 and from that time she started to do clandestine work in support of the Partisans. At the end of that year she was accepted as a member of the Albanian Communist Youth. In January 1943 she joined the 20th Brigade and was appointed it’s Youth Secretary. She was killed on the front line, fighting against the Nazis, by a mortar that exploded close to her, in 1944.

The final name, Francesko Sula has the word ‘Italian’ written next to it. It is, perhaps, a little known fact that after the defeat of the Italian invaders in September 1943 a considerable number of the erstwhile invading troops stayed in Albania, joining the Partisans and fighting against the German Nazis. This is the first time I can remember seeing this being commemorated although I’m sure a closer look at the names on either plaques or tombs in other Martyrs’ Cemeteries in the country would uncover other internationalist fighters.

A plaque on the forward face of the monolith has the following inscribed:

‘Lavdi partizaneve trima te Brigades XXte S de luftuan me heroizem per Çlirimin e Librazhdit 10 Nentor 1944’

This translates as:

Glory to the brave partisans of the 20th S[ulmuese] (Guerrilla) Brigade who fought heroically for the Liberation of Librazhd, 10th November 1944

In November 1944 the German Nazi invaders were rapidly in retreat towards Tirana and then the coast. That meant that the towns along the road to Tirana were liberated in stages, that liberation speeding up after the important battle at Berzhite. The final liberation of Tirana being achieved on 29th November 1944.

Location:

GPS:

41.17860602

20.31470298

DMS:

41° 10′ 42.9817” N

20° 18′ 52.9307” E

Altitude:

259.4 m

More on Albania ……