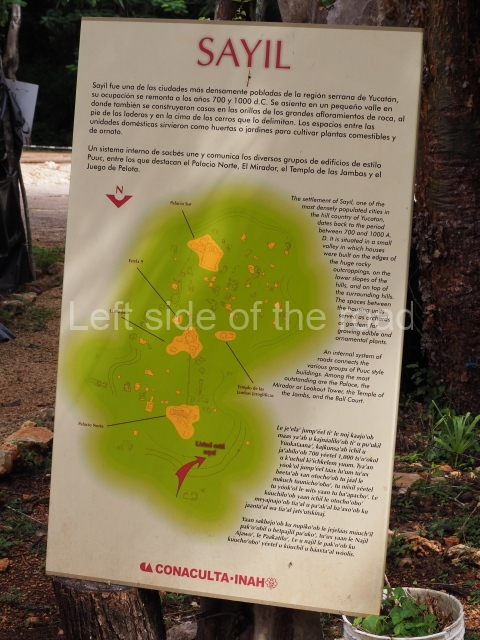

Sayil

Sayil – Yucatan

Location

The archaeological area of Sayil is situated 25 km south-east of Uxmal, Yucatan. To reach it, take federal road 180 and then state road 131 to the site. The Puuc region is characterised by karst landscape and uneven topography, with no sources of surface water, only cenotes and aguadas, natural wells and depressions. One of its principal cultural traits during the pre-Hispanic period was the development of a technology to store rainwater in chultunes or cisterns dug out of the rock. The vegetation in the Sayil area is at different stages of growth, giving rise to a thick layer of secondary vegetation that makes it relatively inaccessible. This vegetation is the produce of the last 400 years of seasonal farming characterised by the cultivation of small plots of land which are rotated every so often when the nutrients of the soil have been depleted. This modern farming method, combined with the low levels of population it sustains, is a stark contrast to the high population levels in the Puuc region during the pre-Hispanic period, especially the Terminal Classic (AD 750-950.)

Pre-Hispanic history

The size of the civic-ceremonial precinct at Sayil was only eclipsed in the region by Uxmal. Near Sayil are various minor sites, including Kabah and Labna. These civic-ceremonial cities are situated at regular intervals of between 10 and 12 km, with dense human conglomerates between larger centres. The density of the pre-Hispanic population was such that in certain areas of the Puuc region it was continuous, leaving very few places without any human presence. The growth of Sayil as an important centre was probably the result of the collapse of other centres and the population decline in the southern lowlands during the 8th and 9th centuries AD. Over the course of the following centuries, the majority of the population in the southern lowlands probably moved to areas with a greater stability in terms of resources or to less populated regions, such as Puuc. The rapid population increase in northern Yucatan is therefore almost certainly related to the decline in importance of Peten in the political and economic history of the Maya area, but also to a major change in rainfall levels and improved farming potential in the Puuc region at the end of the Classic period. Based on the capacity of Sayil to accumulate water in chultunes and on the number of rooms per building, some historians estimate a population of between 4,000 and 8,000 during the Terminal Classic (AD 750-950) and a possible area of influence of 70 sq km with a total population of 16,000.

History of the explorations

Sayil was first visited and its ruins presented to an international public in 1841, after it had been recorded by John Stephens and Frederick Cartherwood. Although numerous travellers and researchers have published their impressions about their respective visits, relatively little is known about this archaeological site beyond the architecture of the core area. Until recently, the most complete perspective of this site, and indeed of any other site in the Puuc region, was the map drawn up by Edwin Shook in 1934 showing the layout of the buildings and documenting some of the most notable structures. Evidence of the principal period of occupation was limited until a few years ago to the existence of certain calendric dates on inscriptions and on the ceramics uncovered during minor excavations conducted at the site by Brainerd in 1958. Most of these pots correspond to the Cehpech ceramic group, which dates from between AD 800 and 1000. Between the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, the University of New Mexico conducted a longer and more detailed archaeological project at the site.

Site description

At its peak, Sayil may well have comprised four architectural groups of varying sizes and importance: one to the north, another two along the causeway running north-south through the site, and the largest to the south-east. The main settlement is concentrated in the bottom of the valley, where five main groups are arranged in an approximate north-south axis along the main causeway. The location of the settlements not directly associated with the causeway is determined by the presence of limestone rocks, which were required for the construction of chultunes. The site continues, practically in all four directions, to the foot of the hills that form the valley

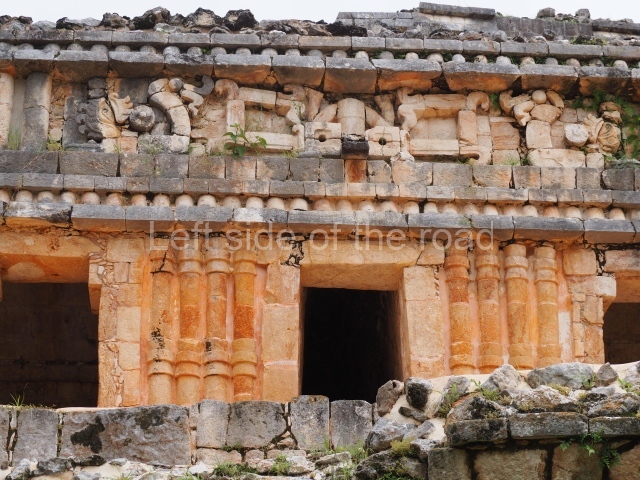

Palace.

This is the best known building at Sayil, being noted for its sheer scale and decoration. In certain publications it is referred to as the Great Palace or the North Palace. It was built on ground that had been levelled and adopts the form of a vaulted group on three stepped tiers comprising over 90 rooms; its basic function was to serve as the residence of the governor’s family and closest circle. The main facade faces south and rises from a platform which also marks the beginning of the causeway that leads to the other groups that form the urban landscape of Sayil. The first two levels are defined by ‘tripartite’ entrances which eventually lead to each of the rooms inside the building. The width of these opening was achieved by a novel technique in the Maya area: the use of modestly decorated, monolithic columns, which permitted the creation of large, well-lit surfaces covered either by flat roofs or corbel vaults. The facades display a harmonious and balanced combination of various decorative panels: on each level, the facades have a different type of decoration, the most notable being the middle section with its complicated mosaic designs, typical of the Puuc style. On the bottom level, the west facade once displayed medial moulding combined with zoomorphic masks, the latter no longer visible. On the east facade, the smooth panels are combined with a frieze decorated with colonnettes. The second level offers a magnificent example of Puuc architecture at its height, combining simple entrances with much wider ones and a decorative repertoire defined by the use of colonnettes on the lower frieze. Medial and upper mouldings decorate the short sections of these same elements which alternate from wall to frieze between the doorways, the portico openings and the sculptural decoration. The walls are decorated with colonnettes with ataduras or moulded bindings in the middle and at the ends, while the frieze, simple and bare, serves to accentuate the wall decoration. On the frieze above the central openings are robust stucco masks representing the front view of a long-nosed deity, flanked by serpents shown in profile. The decoration of the lower levels of the Palace contrasts enormously with that of the top level, which is much simpler. This level was added at later date and part of the lower levels must have been filled in to support the weight of it.

Mirador.

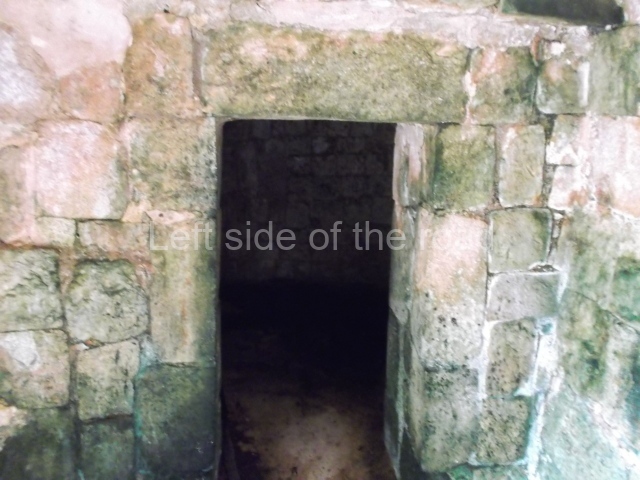

Situated next to the south end of the causeway and built on a stepped platform, the reconstructed building we see today is defined by its high corbel vault and an equally high roof comb. Nowadays, the facade is bare and simple, with medial moulding that must have contrasted with the roof comb which still displays traces of butts for stucco anthropomorphic figures. The building originally contained five rooms, of which only one has survived.

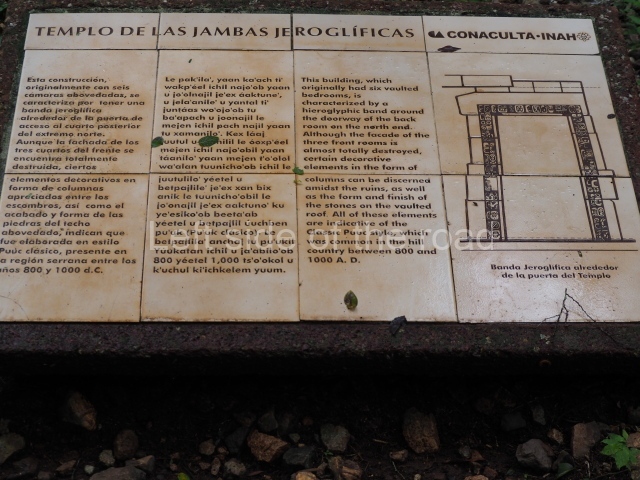

Temple of the Hieroglyphic Lintel.

This forms part of a small quadrangle. It is poorly preserved, with only three of its original rooms still visible today. The north room displays an interesting doorway from the architectural point of view and relatively rare in the Maya area: a band of 30 glyphs, many fairly well preserved, decorates the jambstone and lintel of the main entrance to the building.

South Palace.

This is a fairly simple, three-room structure with a central portico defined by two columns, lintels and capitals with carved figures and anthropomorphic deities. It is the largest building in the south group. A two-level structure, its main facade faces east. On the ground floor the rooms are arranged around a solid volume. The central room on the facade has three doorways. Nearly all of the decoration is articulated by horizontal lines of colonnettes.

Rodrigo Liendo Stuardo

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp 375-378.

Sayil

1. Palace; 2. Temple of the Hieroglyphic Lintel; 3. Mirador; 4. South Group.

How to get there:

Not easy if you don’t have your own transport. There are no buses or colectivos that run along this road. Although the three sites (Labna, Xlapak and Sayil) are all within a 15km stretch of the road unless you hire a taxi from Santa Elena (expensive) you have to depend upon your wits, imagination and good luck.

GPS:

20d 10′ 47″ N

89d 39′ 16″ W

Entrance:

M$70