More on the Maya

Mixco Viejo

Location

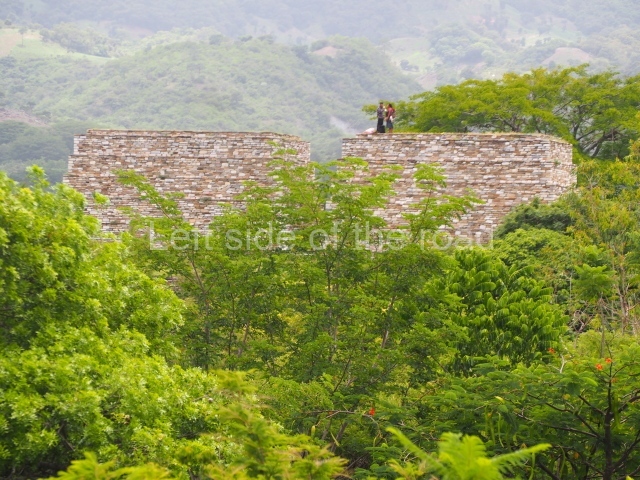

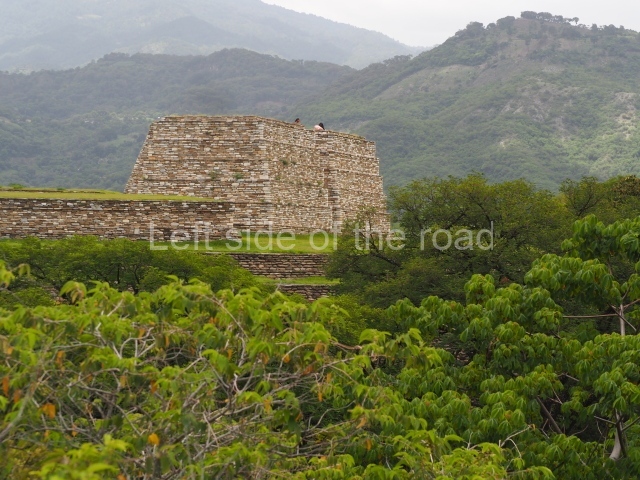

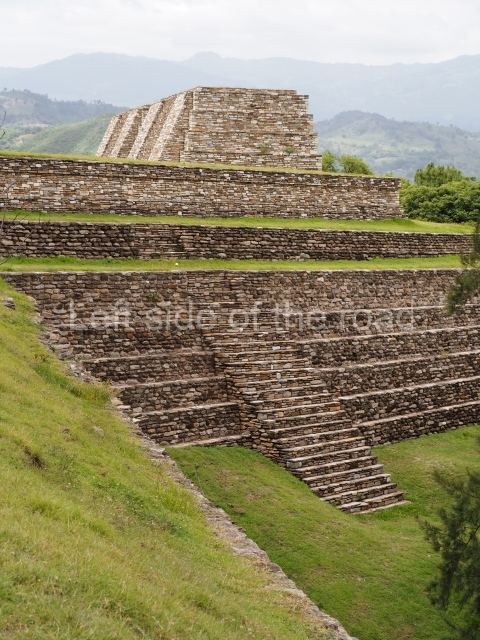

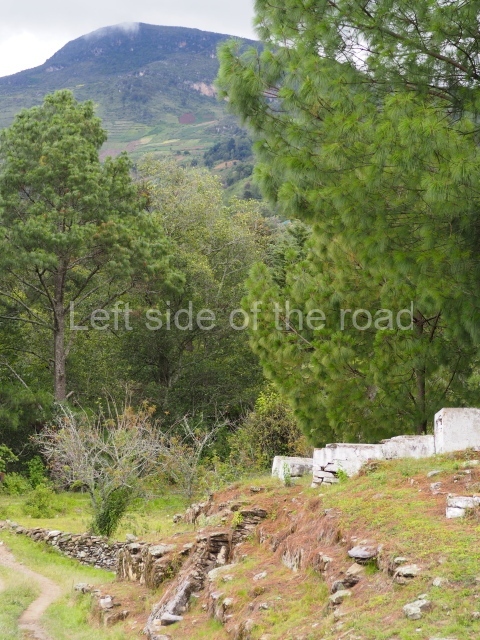

This is one of the most representative Postclassic archaeological sites in the Guatemalan Highlands. Its architecture and landscape combine to make it one of the finest exponents of a defensive site or fortress city from the last period of the pre-Hispanic period. It is situated on a plateau surrounded by deep ravines, 61 km north of the present-day Guatemala City.

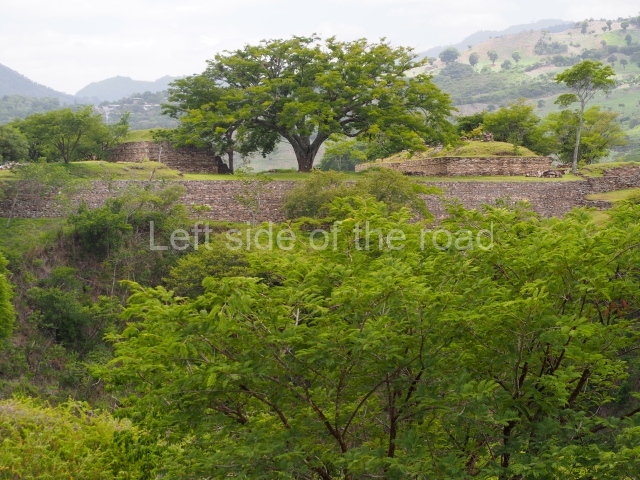

The confluence of the rivers Motagua and Pixcaya flows in deep ravines all around the site. The predominate climate is hot and dry, and the vegetation is of the thicket type. The site, which covers an area of approximately 1 km and stands 880 m above sea level, contains over 100 structures distributed in several groups designated by letters. Each group consists of one or more temples, several platforms for supporting large houses or palaces, and a ball court, all situated around enclosed or open plazas.

Pre-Hispanic history

According to Fuentes and Guzman, the fortress at Mixco Viejo was a virtually impregnable military bastion due to its location and magnificent defensive position. However, following cruel battles waged on the plains around the site, a group of prisoners revealed a secret access to the Spaniards, enabling them to take the defenders of the fort unawares and defeat them in a campaign led by Pedro de Alvarado.

The ruins of Mixco Viejo were identified by Karl Sapper, who visited the site at the end of the 19th century. The next visitor was A. L. Smith, who included it in his book Archaeological Reconnaissance in Central America, and in a chapter in his Handbook of Middle American Indians. The first excavations were conduced by Henri Lehmann of the Franco-Guatemalan Mission in 1954. According to historical records, the site was the capital of the Pocomam kingdom, whose present-day descendants live in the town of Mixco. However, a detailed ethno-historic research project led by Robert Carmack proved that Mixco Viejo was the capital of the Chajoma Maya, a group belonging to the Caqchikel race, whose present-day home is the town of San Martin Jilotepeque. Carmack believed the correct name of the site to be Jilotepeque Viejo, and that the Pocomam capital was the ruin known as Chinautla Viejo, not far from the present-day Zone 6 in Guatemala City. However, out of habit, this important site has continued to be known as the ruins of Mixco Viejo.

Site description

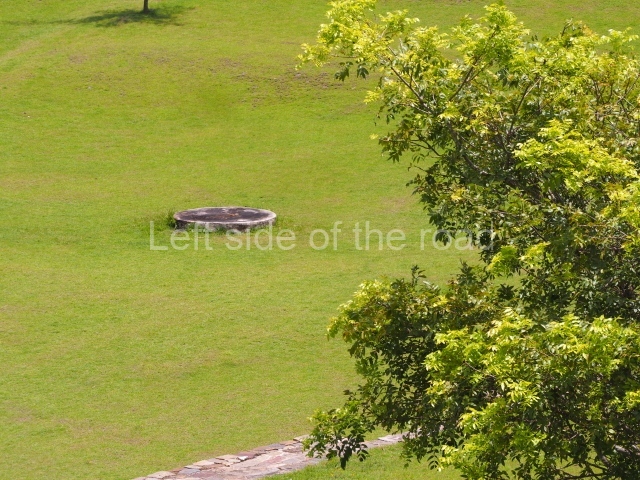

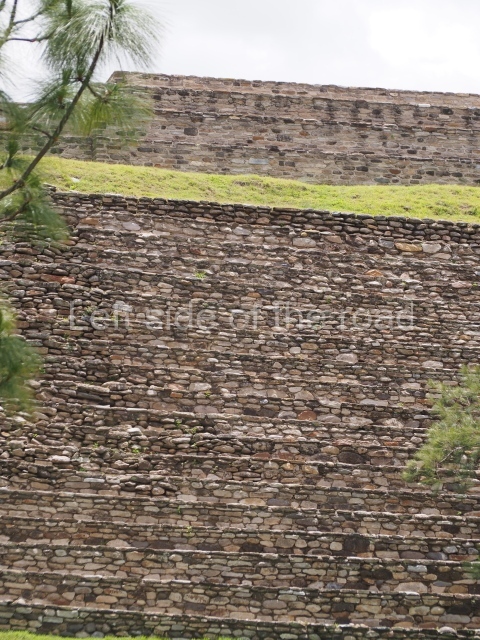

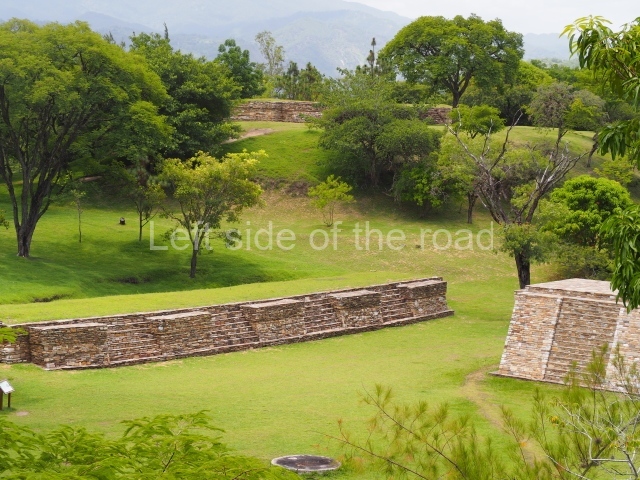

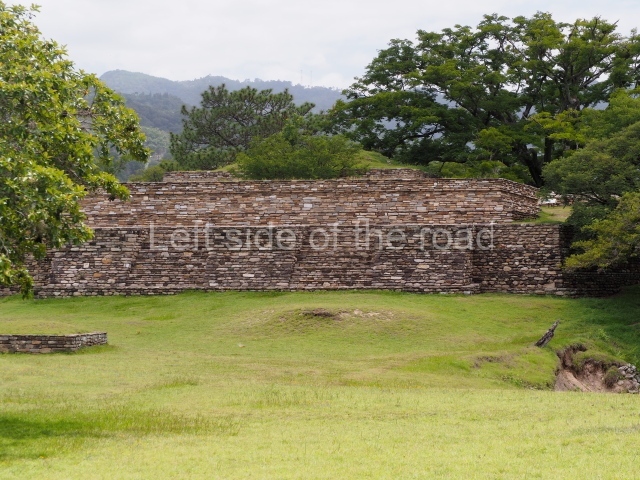

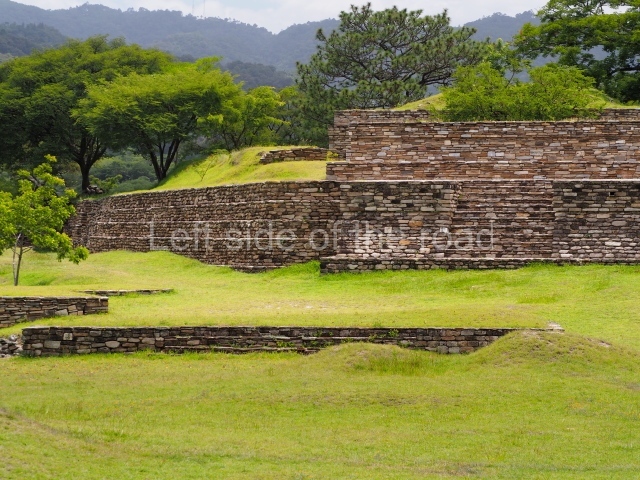

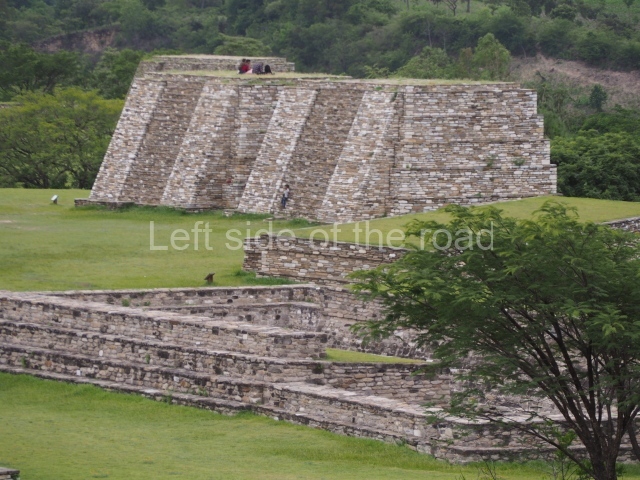

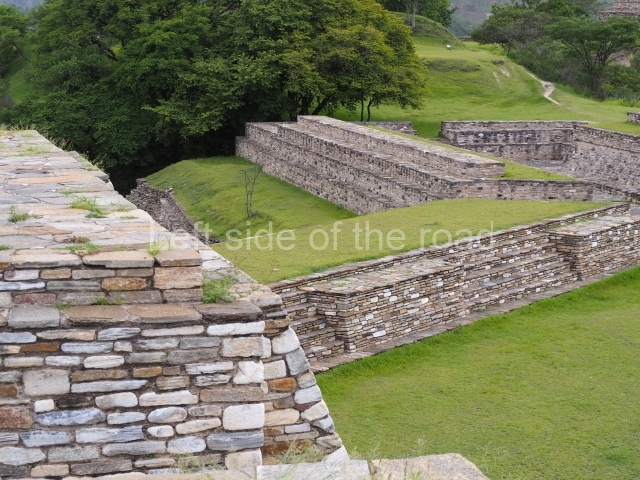

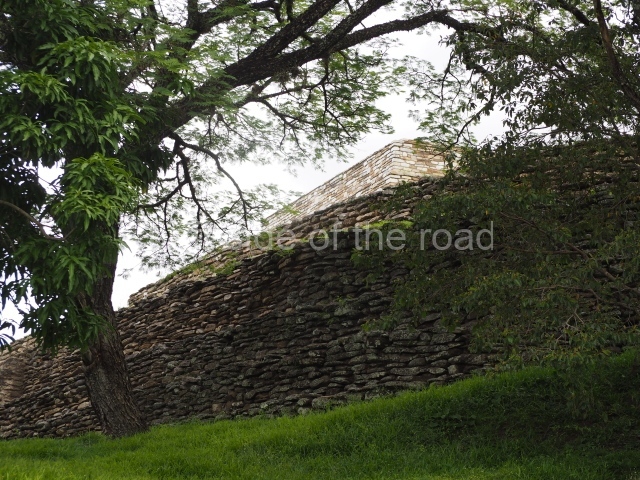

The site is divided into groups designated by the letters A to F, the principal precincts being A, B and C, corresponding to the most important lineages. The other three groups were largely peripheral. Another six groups, smaller in size than the former, are scattered around the edges of the site. In general, the temple structures faced the west, although there are variations, while the platforms supporting the largest houses faced the banks of the ravines. Both the temple structures and the elongated platforms were surmounted by constructions made out of perishable materials. The principal material used at Mixco Viejo was slate or schist for the external face of the walls and a clay and pumice mixture for the filling. The facades of the most important buildings were decorated with stucco and then painted, and in certain cases there must have been murals, although none of these have survived. Even the floors of the ball courts may have been covered by a layer of stucco. The tallest buildings corresponded to the temples – nine in total – some of which stood 8 m high. The most representative were the double temples or twin pyramid platforms, which recall the architectural style of the Mexican plateau during the Postclassic. The elongated platforms that supported the ‘large houses’ can be found in each principal group, forming plazas. These had numerous accesses formed by sloping balustrades with vertical finial blocks. The ball courts were of the closed, I-variety. Wide and extremely long, they were accessed by stairways at both ends. The parallel walls sloped, in the talud style, with vertical finial blocks, and they were lined with benches. The markers, embedded in the top of the walls, were stone carved butts in the shape of a serpent head, with an anthropomorphic head emerging from the open mouth.

Group A

This is situated in the north-eastern section of the site and consists of a series of buildings distributed around two plazas, the most predominant constructions being the elongated platforms. There is a temple platform with a double stairway in the middle of one of the plazas and a sunken ball court in relation to the level of the plaza. One of the plazas contains various small shrines and a series of small platforms for supporting dwellings made of perishable materials.

Group B

This is situated in the middle of the site on a large plateau surrounded by small ravines. It consists of several structures distributed around a large enclosed plaza which includes twin temples, 6 m high, platforms for palaces or large houses, shrines and another sunken ball court. Larger than the former ball court, this construction is 44.5 m long and 9 m wide between the benches and 17 m at the ends. Except for one platform with four access stairways, the others have only two or a single stairway. Its most outstanding characteristic is a large retaining wall to the south, which reinforced the hill on which the group stands.

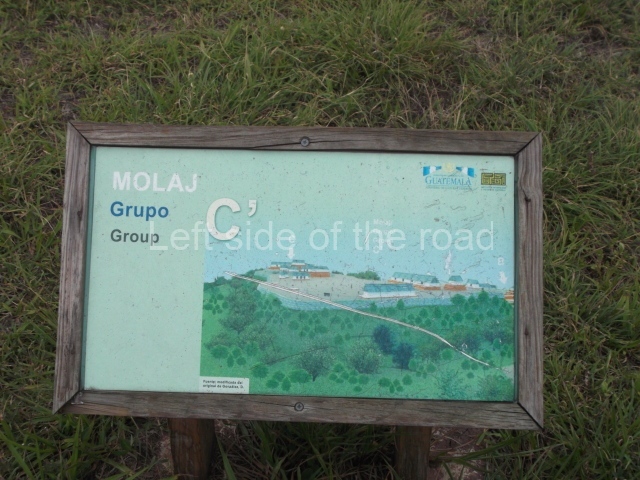

Group C

This is situated further west and has an uneven appearance in relation to the former groups. It is divided into two sub-groups of structures which run east-west, the principal constructions being Pyramid Cl, built in several stages and standing 6 m high, and Platform C2. The latter is the largest building at the site, measuring 47×14 m and standing over 4 m high. It is composed of two tiers with several stairways on the top tier. Further to the north, behind this large platform, are various other structures, possibly corresponding to a residential group.

Edgar Carpio

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp488-490.

1. Group A; 2. Group B; 3. Group C; 4. Group D; 5. Group E; 6. Ball Court; 7. Double Pyramid.

How to get there;

A bus passes along 1A Avenida at its junction with the PanAmerican Highway in Trébol. This is the starting point for buses to Antigua and other routes heading north. There’s a bus whose destination is Pachalum which passes through at around 09.15 (it might be early or late). Ask the lad who’s there everyday (so he told me) for more information. Q25 each way. There’s a bus which passes the approach road to the ruins returning to Guatemala City at 15.00 and 16.30, more or less.

GPS:

14d 52’ 26” N

90d 39’ 45” W

Entrance:

Q50