Yaxchilan – Chiapas

Location

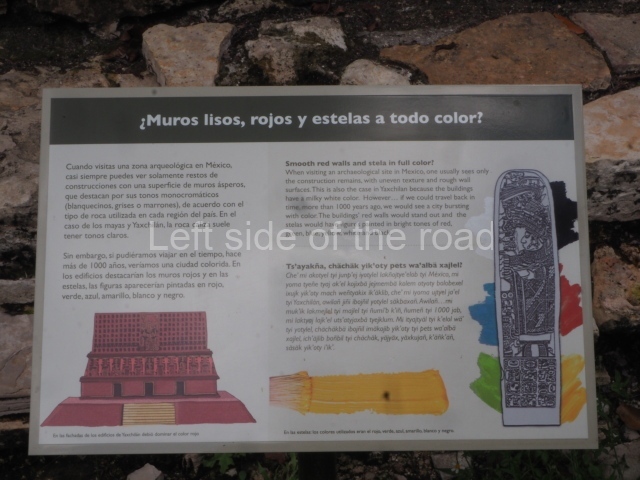

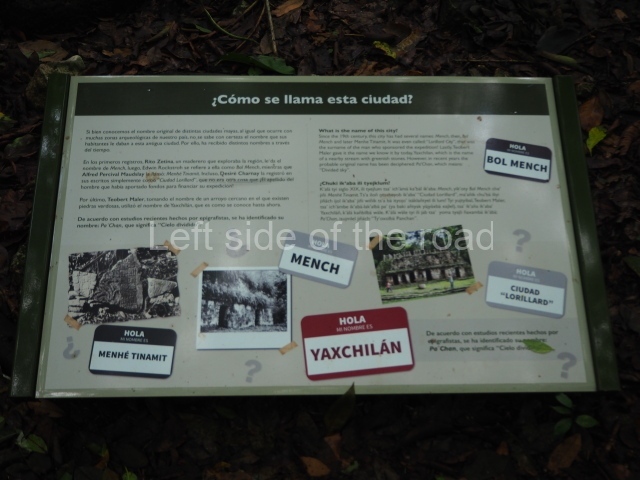

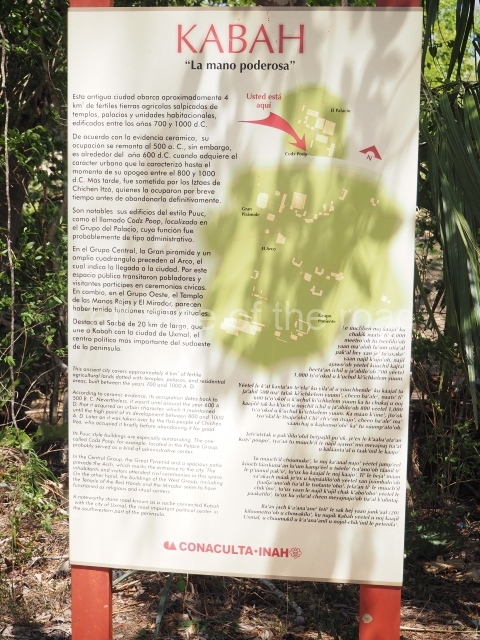

This site is located amid a thick blanket of tropical rainforest on the banks of the River Usumacinta. It emerged around AD 350 and survived until 810. In pre-Hispanic times it was known as Pa’ Chan (Divided Sky). Its architectural layout is adapted to the topography of the terrain and the river, with the buildings arranged from east to west on a large plaza delimited to the south by elevations that served as foundations for the constructions. Yaxchilan is famous for its numerous finely carved monuments, which tell us something of the life of a long sequence of rulers and dignitaries over the course of six centuries. The principal means of representation is the stela, although there are also 58 carved lintels. The nearest towns are Palenque in Chiapas and Tenosique in Tabasco. There are access roads from both places, but only Palenque offers a bus route and travel agencies. Take the road to Chancal, from there to Frontera Corozal or Frontera Echeverria, on the banks of Usumacinta, and then hire a motor boat to cover the rest of the journey to Yaxchilan. From Frontera Corozal the journey downstream by motor boat takes approximately 30 minutes. The motor boat service runs all year round and can be booked on the spot through indigenous cooperatives or at any travel agency in Palenque.

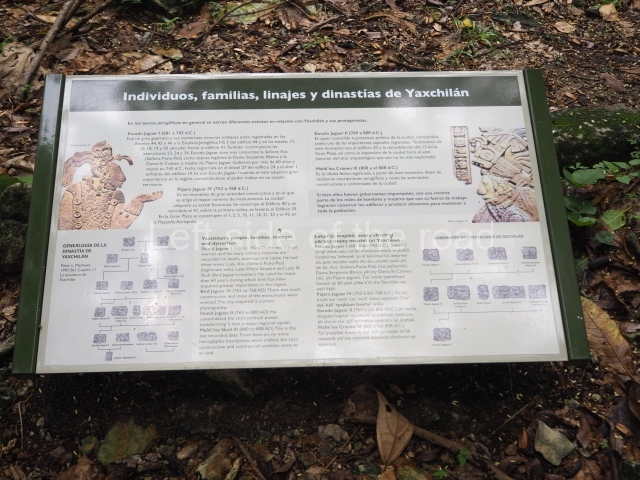

Pre-Hispanic history

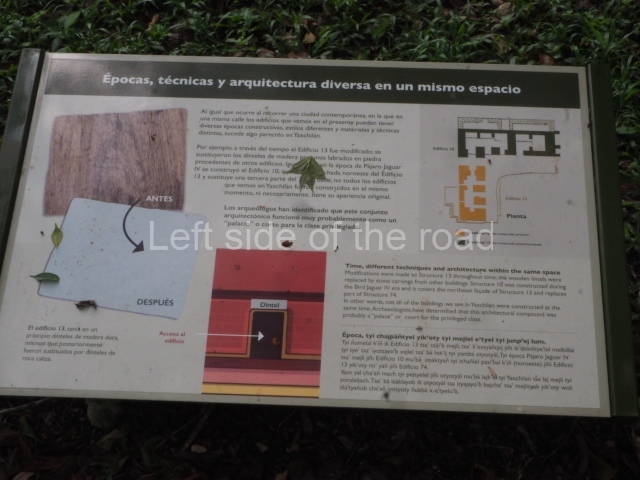

Yaxchilan is one of the great Maya sites from the Classic period, evolving from a tiny village of farmers and hunters into a prominent city. It is thought to have gained importance during the rule of Mahk’ina Skull I, who was lord of Yaxchilan around AD 410. When Mahk’ina Skull II acceded to the throne in 526 the city became a regional capital, as evidenced by the presence of its emblem glyph at other sites. It also exerted a certain political influence over sites such as El Chicozapote, Anaite, La Pasadita, El Cayo and La Mar. Amund AD 600 the rulers suddenly began to erect stelae, undoubtedly reflecting a period of political Instability. Thereafter, the record of rulers was renewed in 630, when Bird Jaguar III acceded to the throne. His son, Shield Jaguar II, who took the throne in 681, was responsible for the most important expansion of the city and his reign was characterised by constant struggles with other cities, over which he managed to maintain control. Shield Jaguar II had three wives: Fish Nst, Snake White and Lady Ik Skull, who was the mother of the next ruler, Bird Jaguar IV. Following the death of Shield Jaguar II (around 742), it would appear that his third wife ruled for the next 10 years. Under Bird Jaguar IV, Yaxchilan acquired its definitive appearance and consolidated its hegemony. This ruler commissioned buildings and monuments representing himself and his wives and deputies, which suggests the need to strengthen and expand political alliances to guarantee Mobility. In 757, when Shield Jaguar II was five years old, his father Bird Jaguar IV named him his official heir. Shield Jaguar II is shown taking a prisoner (around 787) on the central lintel of the Temple of the Pointings at Bonampak. In the final record for this dynasty, Lintel 10 (c. AD 808) shows Mahk’ina Skull III, who was apparently the son of Shield Jaguar II. Of this long line of rulers, Bird Jaguar IV (Yaxun Balam IV) is perhaps the best known. He acceded to the throne ot the mature age of 44 on 29 April 752 and became one of the most dynamic rulers of the Classic period (AD 250-830), creating numerous sculptures and texts In his 16-year reign: stelae 1, 3, 6, 9, 10, 11 and 35; lintels 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 16, 21, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 38, P), 40, 50 and 59; the hieroglyphic stairway of Temple H; and altars 1, 3, 4 and 9. He sought important marriage Alliances with a number of high-ranking women from neighbouring kingdoms – Lady Great Skull, Lady Wak Tun from Motul de San Jose, Lady Wak Jalam Chan Ajaw from Motul de San Jose and Lady Mut Bahlam de Hix Witz – and proclaimed his legitimacy as ruler by commissioning numerous public texts. He was also responsible for the Architectural transformation of the site. The area around the Main Plaza, composed of several natural differences In the level of the terrain, was levelled and turned into a single monumental architectural group. At least 12 different buildings were erected or modified during his reign.

Site description

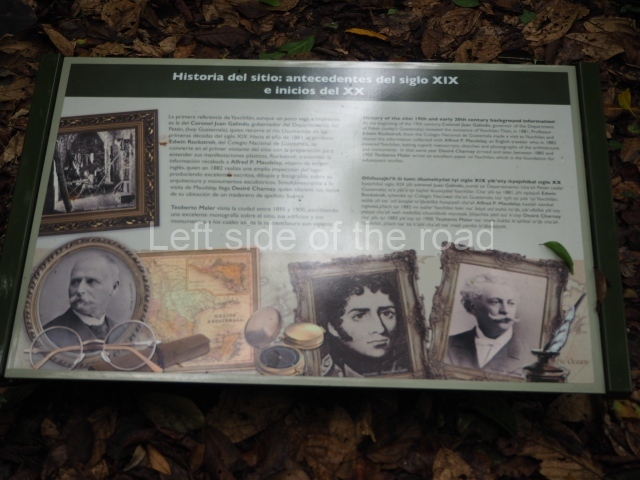

The present-day classification of the structures at Yaxchilan is based on the system devised by Teobert Maler, with adaptations by Silvanus Morley in 1931 and Roberto Garcia Moll in the 1970s. It adopts an ascending sequence of Arabic numerals. The association of buildings with stelae, lintels and monuments is particularly complex And the most orderly tour of the site is as follows:

- Structures situated along the banks of the river and In the Great Plaza: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 66, 67, 68, 74, 80 and 81.

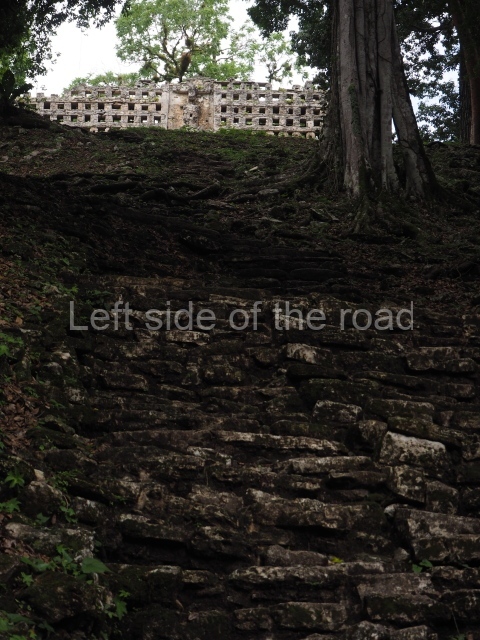

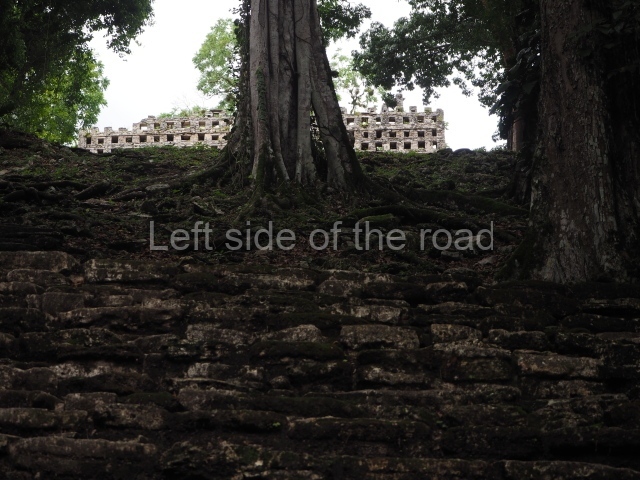

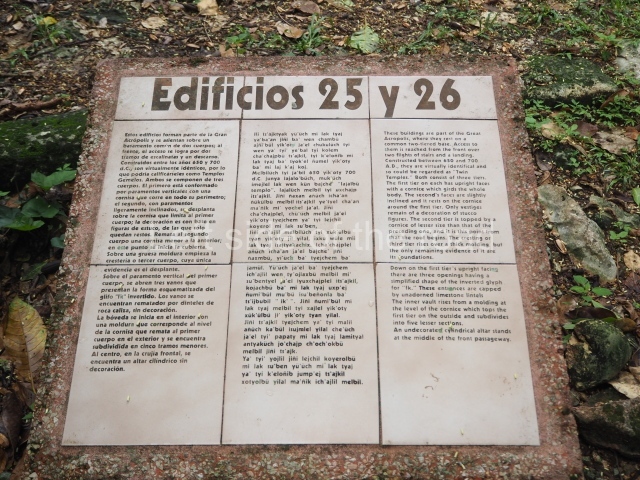

- Structures on the second terrace: 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30.

- Central Acropolis: 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38.

- South Acropolis: 39, 40, 41.

- West Acropolis: 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 87.

- North-West Group: 84, 85, 86.

- South-East Group: 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 88.

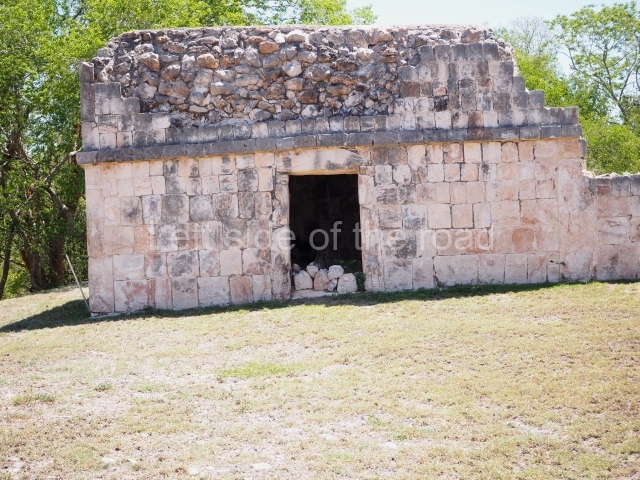

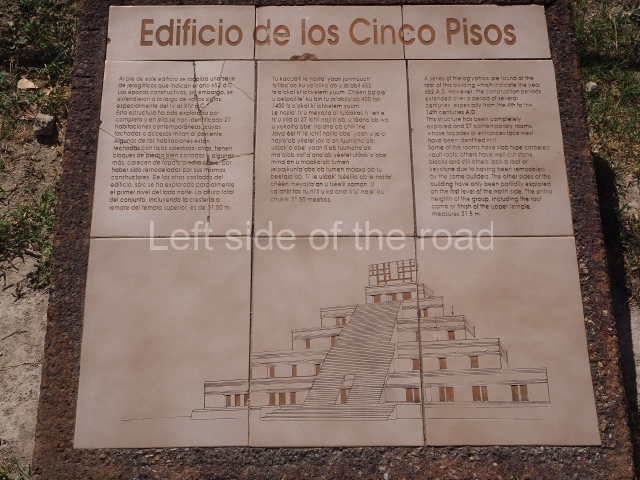

Structure 1.

This overlooks the Main Plaza from a natural terrace standing approximately 3 m high. Situated in a short passageway leading to the South Acropolis, it accommodates four stone lintels (5, 6, 7 and 8) with inscriptions, which Maler removed from their original position in the building to record and photograph. Lintel 8 is situated towards the east. All of the lintels commemorate a date at the end of a Katun (9.16.0.0.0) and the protagonist is Yaxun Balam IV.

Structure 2.

This building has not been consolidated. In 1900 Maler found the remains of two monuments underneath a mound of rubble: Lintel 9 and Stela 30. In 1964 the lintel was taken to the National Museum of Anthropology and History, where it remains on display, the stela (fragment) is associated with an unnumbered mound to the east, near Structure 2. It was found by the first keeper of the archaeological area in 1934. Morley published a minor reference to it in 1937. The fragment comes from the top of a stela and depicts a cartouche with a figure.

Structure 3.

In 1897 Maler reported two lintels, one of them completely eroded. Lintel 10 is in a good condition and nowadays protected by a film. It refers to the blood relationship between an unnamed ruler and his father, Shield Jaguar II, whose mother was Lady ‘Perforator’.

Structure 5.

This is a low, elongated platform running parallel to the south-east end of the Main Plaza. It is surrounded by three other low platforms (4, 5 and 8) and no remains of an upper structure have been found. The rear of the building is narrow and falls steeply down to the river. Next to it stands Hieroglyphic Stairway 1, which is composed of 188 individual blocks of stone. Only the risers of the steps are sculpted. Maler described this stairway as ‘the most magnificent he had ever seen’. The glyphs are extremely difficult to read and many of them are completely eroded. The reading order begins at the top left with step 1 and continues across and down. The first step mentions an individual from the Jaguar family, while the next step shows the verb Chum wan (sat on the throne) but the date is totally illegible. The first and second steps display at least another four illegible glyphs regarding accessions to the throne. The events recorded on this stairway would appear to narrate the deeds of an individual called Jaguar and they culminate while Bird Jaguar IV was still alive. This monument seems to be the only complete list of rulers known to date at Yaxchilan. It was built during the reign of Yaxun Balam IV.

Structure 6.

The excavations conducted in 1976 provided a partial interpretation of the function of this building: to connect the Main Plaza to the area near the river. Numerous examples of Lacondon ceramics were found, the product of rites conducted by this group in recent times. The latest incense burning ceremony was recorded in 1985. Nowadays, Structure 6 is situated on the banks of the river, which flowed further to the south in the pre-Hispanic period. Some of the structures at the site were destroyed when the river was diverted in recent years. The excavations identified a 5-metre stairway leading down from the Main Plaza to structures 6 and 7.

Structure 7.

First recorded by Maudslay (1889) and consolidated and restored by Garcia Moll (1976), this structure is composed of two parallel galleries accessed on the east side. Like Structure 6, its facades overlook the river and the Main Plaza. Discernible on the frieze are the remains of a mask representing a supernatural creature, while the cream colour that once covered the internal walls is still partly visible. It is very similar in style – thick walls and wide access at the front – to Structure 6, which suggests that it was built around the same time.

Structure 9.

This structure is covered by thick vegetation and therefore barely visible. According to Maler, it has three entrances and two parallel galleries, and there are two associated altars. It is also associated with Stela 27, which bears one of the oldest inscriptions in the Usumacinta region. It mentions a ruler called Knot-Eye Jaguar, who is also named on Lintel 12 at Piedras Negras.

Structure 10.

Situated on a 3-metre-high platform, this structure consists of two more or less adjacent rooms, each one a different size. The north-west room has three entrances and the south-east one two entrances. Three carved lintels were found. The north-west room only has a lintel above the central entrance (Lintel 29), while the south-east room has two (30 and 31). The INAH excavated these buildings in 1979. Lintels 29 and 31 were found by Maler and Maudslay in situ. However, the archaeological project conducted in the 1970s found them on the floor and broken. All three lintels were restored and put back in their original position. They mention the date of the birth of one of the last rulers, Yaxun Balam IV. The three lintels record an 819-day count prior to his birth, the date of his birth, the date of his enthronement, and the end of two important cycles.

Structure 11.

This corresponds to a small residential group with a central courtyard. Three entrances give on to a small courtyard formed by the rear part of structures 10 and 74. The rooms overlooking the river are completely in ruins, although the floors are still visible. This building originally accommodated Lintel 56 which Maudslay reported and sent to Europe for display in the British Museum. However, it ended up by mistake at the Museum fur Volkerkunde in Berlin and was destroyed during the bombing in the Second World War. Fortunately, there is a copy at the British Museum. Nowadays, the structure has been reconstructed with three bare stelae in situ. The text mentions the inauguration of the building by one of the most important women in the history of Yaxchilan: Lady Xoc.

Structure 12.

This is situated in the Central Plaza, next to the Ball Court. Maudslay was the first to report the building and mentions the existence of two lintels. Maler reported having entered the building and found another two. On its 14th mission to Central America, the Carnegie Foundation excavated it and found another three lintels. Finally, Garcia Moll of the INAH found the last of a series of eight lintels that provide a continuous inscription commissioned by Ruler 10 of Yaxchilan; this mentions the nine previous rulers, his own date of enthronement and the kinship ties that link him to this line of rulers.

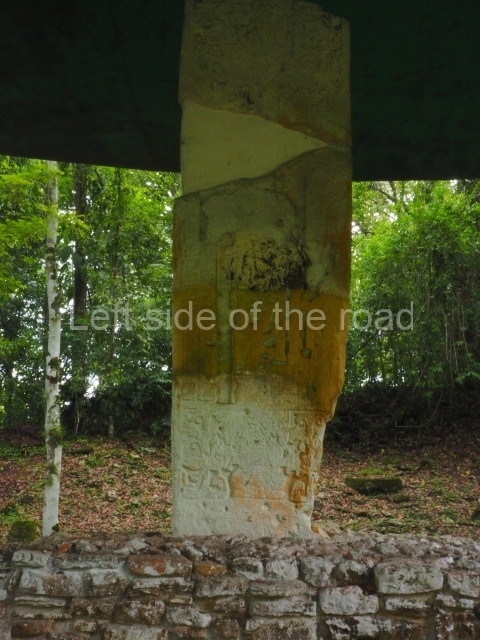

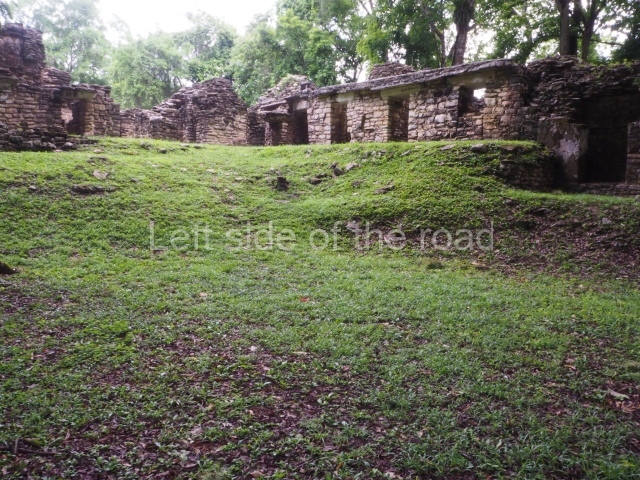

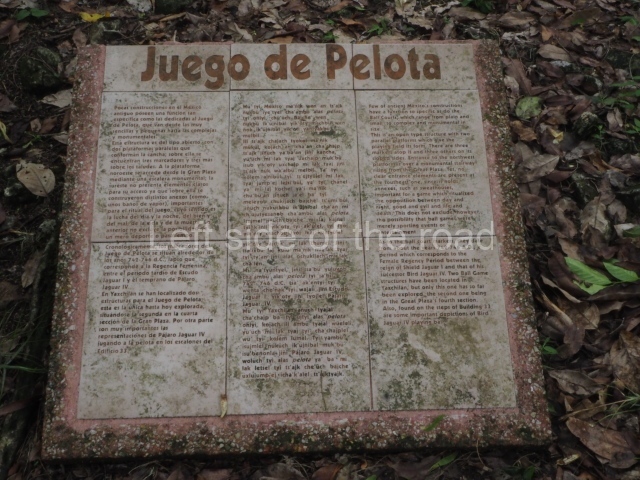

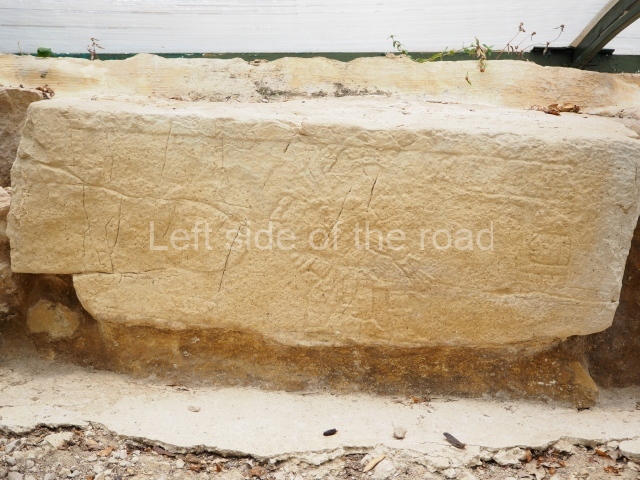

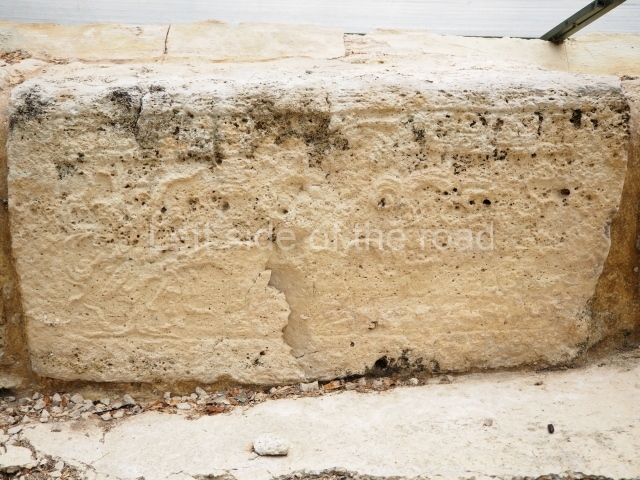

Structure 14 or ball court.

This is situated in a large area of the northern part of the Central Plaza. The group is composed of two parallel platforms, about 2.5 high, but asymmetrical: one is 13.8 m long and the other 18 m long. Five stone discs associated with this structure were found, all with a similar diameter (65 cm) and height (45 cm). They were distributed at the level of the playing area, so the stucco cladding did not conceal them. Although in a poor state of preservation, their design seems to show an individual seated in a cross-legged position on a throne which bears the image of a mythological creature. Cartouches around the central image depict images of what are probably important ancestors.

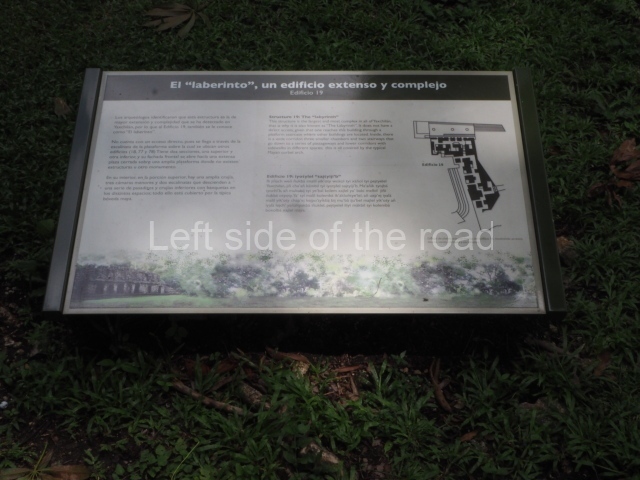

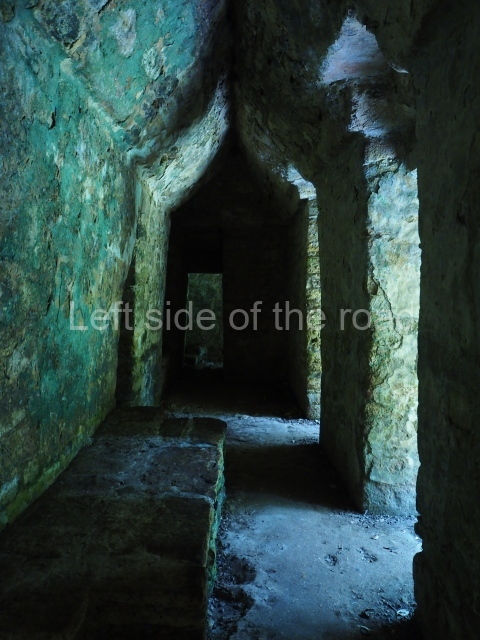

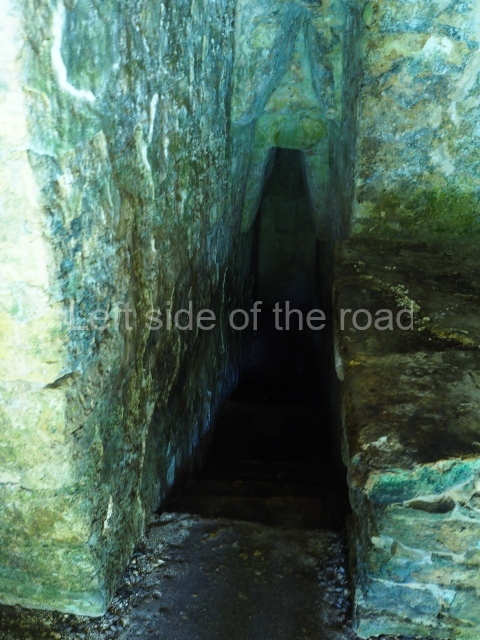

Structure 19.

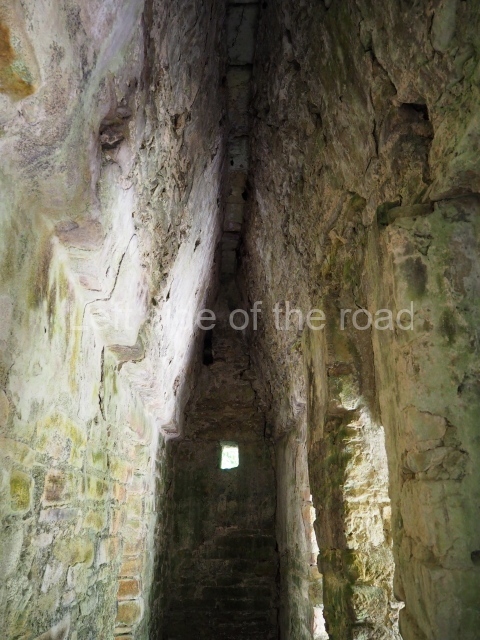

This now serves as the main entrance to the site and a tour of this structure is an unforgettable experience. The ground plan is extremely complex and we do not know what the original plan was like. It is composed of nine vaulted chambers connected by 16 galleries, also vaulted, situated on three different levels. The two lower passages are practically below ground level. This group of chambers and passageways, now home to insects and bats, was filled in with pebbles and mud during the pre-Hispanic period and excavated during the 1970s by Garcia Moll. The top level overlooks the Main Plaza. The main facade displays four doorways. Between the openings are a series of niches embedded into the wall, creating the effect of yet more entrances. Running above them is a frieze with a double cornice. The doorway at the west end leads to a stairway and a lateral chamber occupied almost in Its entirety by a large bench. A small vaulted room leads to a stairway with seven steps descending to the lower levels of the structure. Maudslay was the first person, in 1882, to report and describe Altar I, a circular sculpture opposite the main entrance to the top level of the structure. Nearby is another very similar altar, although nowadays in a very poor state of preservation. The greatly eroded texts on this altar make a fleeting mention to the date 61 x 12 Yaxkin (AD 742) as the death of Itzamnaaj Balam II. Although produced after this ruler’s death, it nevertheless records important events from the latter days of his reign. The architecture of the building is similar to that of structures 20 and 30 in terms of the height of the vaulted ceilings and the width of the walls. This suggests that it is a slightly later building.

Structure 20.

This is situated on the first terrace on the north side of the Central Plaza. Opposite it, in the plaza itself, are five stelae commissioned by Itzamnaaj Balam II, each with a circular altar. This group of monuments is the focal point of a group of structures: 4, 5, 8 and 20. Flanking the access stairway are another three structures. The top step, in front of the threshold to the building, is carved (Hieroglyphic Stairway 5). Three doorways lead to a vaulted chamber. The facade is organised in such a way that the doorways divide the wall surface into three sections, all identical in size. Above the doorways is a frieze composed of three niches which contain the remains of human figures wearing armour, carved in stone and covered with stucco. These remains suggest that the figures formed part of a scene composed of human figures surrounded by supernatural figures (the monster Cauac) and aquatic plants, alternating with niches containing human figures seated on zoomorphic thrones. Six stelae (3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 33) stand opposite Structure 20 and there are three carved lintels above the doorways. Stela 3 was transferred to a platform at the south-east corner of the Central Plaza, very close to Structure 20. This is the best preserved stela but all of them are fragmented. Stela 33, a recent find, is carved on both faces like the rest of this group. The longest text appears at the top of one of the faces and mentions the end of a Katun. It was commissioned by a ruler whose name has been completely eroded. The second text mentions Itzamnaaj Balam II and his son Yaxu’un Balam IV. Visible on the other side is a cartouche with the image of an ancestor and what looks like a celestial monster. Of the three lintels that adorned the entrance, two remain in situ while the missing one was transferred to the National Museum of Anthropology and History in 1964. The hieroglyphic stairway was excavated during the consolidation works, photographed, drawn and then covered up again for its protection.

Structure 21.

The consolidation and restoration of this structure in 1983 yielded two important monuments: a small stela carved on both sides and a well-preserved stucco mural on the rear wall of the inner chamber. The mural displays traces of red and blue paint. The Interior of this structure must have been completely covered with stucco decorations. The three doorways lo the building had carved lintels (15, 16 and 17) but Maudslay sent them to the British Museum in 1883.

Structure 23.

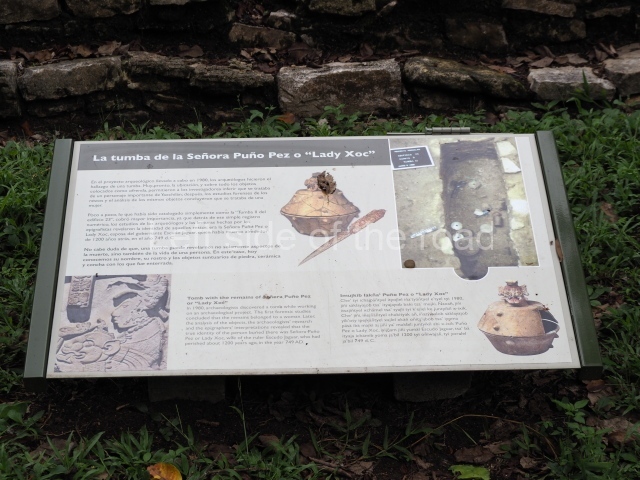

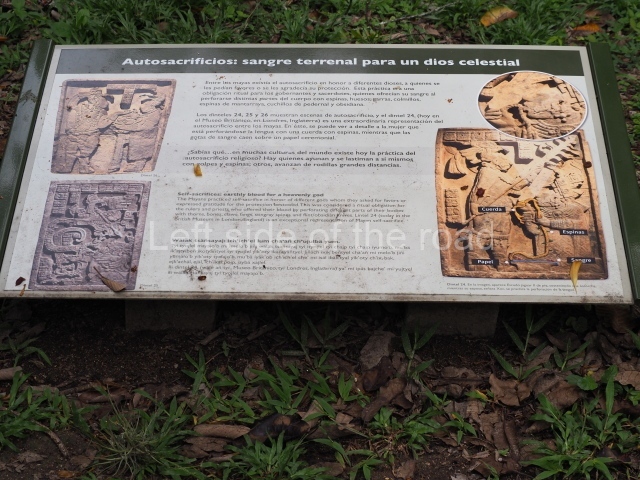

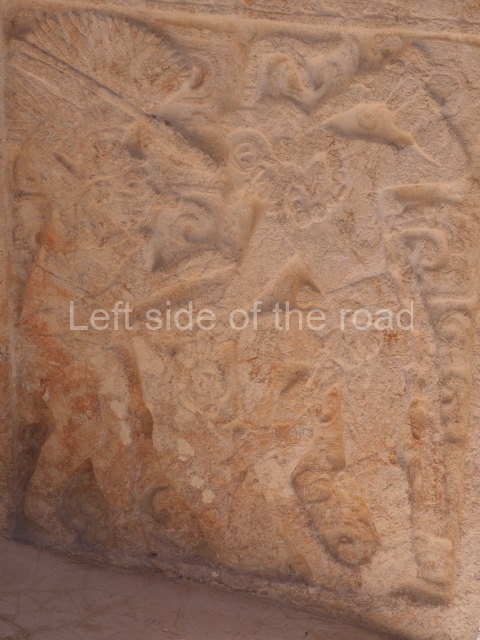

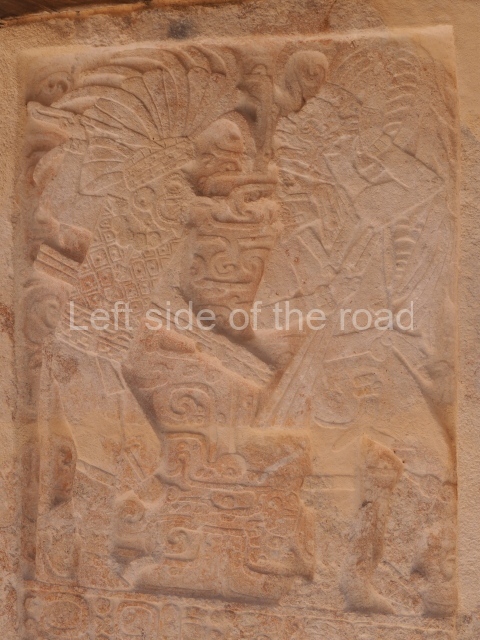

This is one of the most interesting structures because it yielded three of the most fascinating reliefs ever found in the Maya area: lintels 74, 25 and 26. The structure is mentioned in these loxts as yotoot, meaning ‘house of the Lady Xoc’, the principal wife of King Itzamnaaj Balam III. The ruins of this ‘house’ are the second towards the west of the great stairway leading to Structure 33. They consist of two parallel galleries, each divided into several sections. Except for the south-east corner, the vaulted ceiling has all but collapsed. This is a massive construction whose exterior walls measure 2.59 m from base to cornice. The vaults add another 4.2 m to the already high walls. Opposite the central entrances nre various U-shaped benches abutted to the wall behind, above which are a series of 30-cm niches, traces of stucco can be discerned on the central pilaster of the rear wall of the central chamber representing the remains of a snake’s body – and there are also traces of red and blue paint in certain details beneath the vault. In 1889 Maudslay tiansported lintels 24 and 25 to the British Museum, where they remain on display today. Maler excavated l Intel 26 near the north door of the structure and in 1964 the INAH sent it to the National Museum of Anthropology and History. Lintel 23 was found during the excavations in 1979 and returned to its original position. The narrative on the three lintels begins on l intel 25, with Lady Xoc celebrating the enthronement of her husband Itzamnaaj Balam II in 681 and Invoking an important ancestor by performing a bloodletting ritual on her tongue. The ancestor is shown in the mouth of a mythological creature, half serpent half centipede, garbed in the characteristic elements of the Teotihuacan god Tlaloc. The associated text identifies this personage as a dedication to the patron god of Yaxchilan, Aj K’ahk O’Chaak, probably an allusion to Itzamnaaj Balam II himself as the city’s protector. Lintel 24, dated 709, shows Lady Xoc threading a barbed rope through her tongue. The blood runs down the woman’s face and is caught in a basket covered with paper at her feet. Itzamnaaj Balam illuminates and accompanies Xoc with a torch.

Lintel 26 shows the same lady presenting her husband with a jaguar-shaped helmet in 724 as part of a ritual that has yet to be fully interpreted. This building is important for two reasons: it was the first project commissioned by Itzamnaaj Balam II and it has yielded a number of finds. In 1979 Garcia Moll discovered two tombs inside it. Tomb 3 opposite the main entrance contained the remains of an elderly woman with a rich offering comprising over 400 jade beads and 34 ceramic vessels. A text mentions the date of the death of Lady Xoc as 749 and makes reference to a ‘fire’ ritual conducted in her muknal or ‘final resting place’. Tomb 2 contained the remains of a mature man accompanied by an even richer offering, with needles and deer horns carved with inscriptions that mention Itzamnaaj Balam and Lady Xoc.

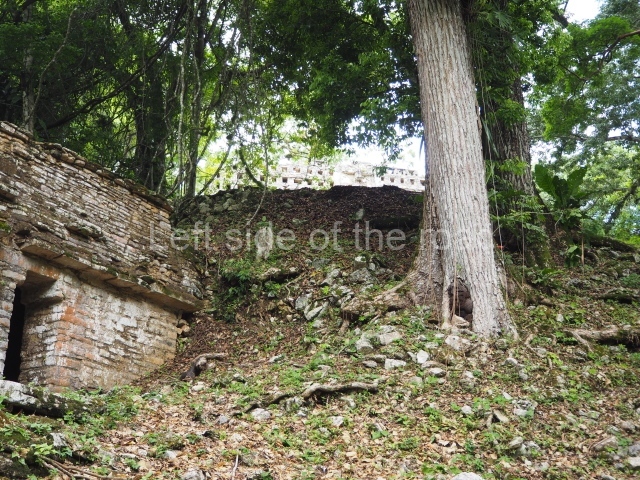

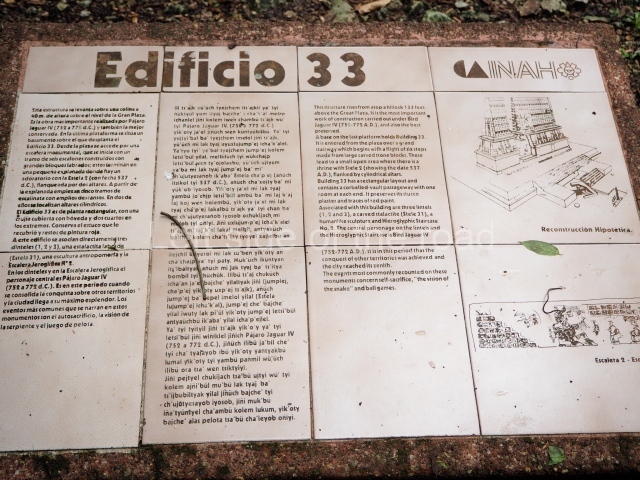

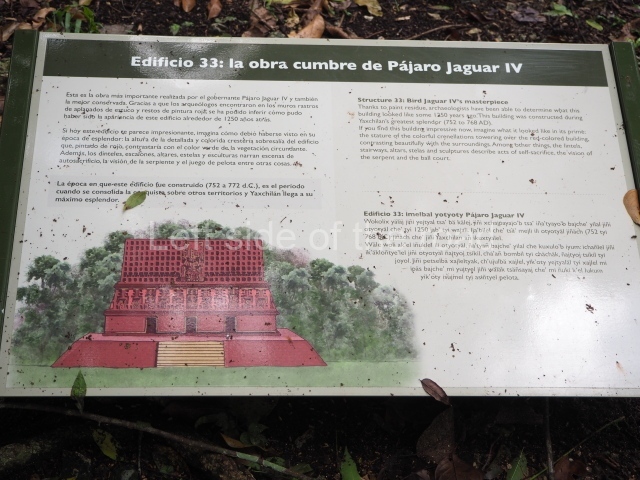

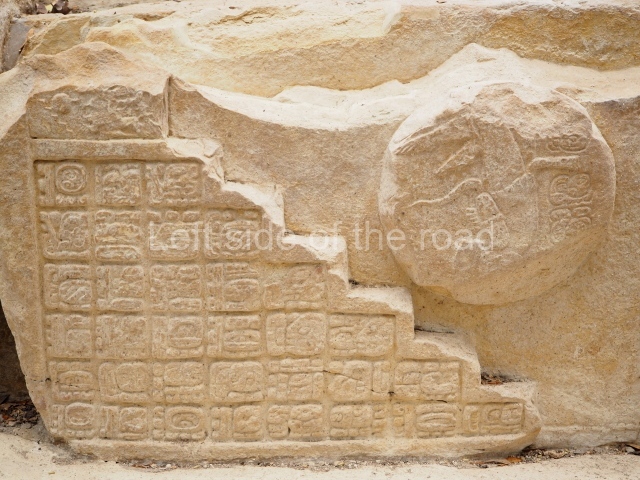

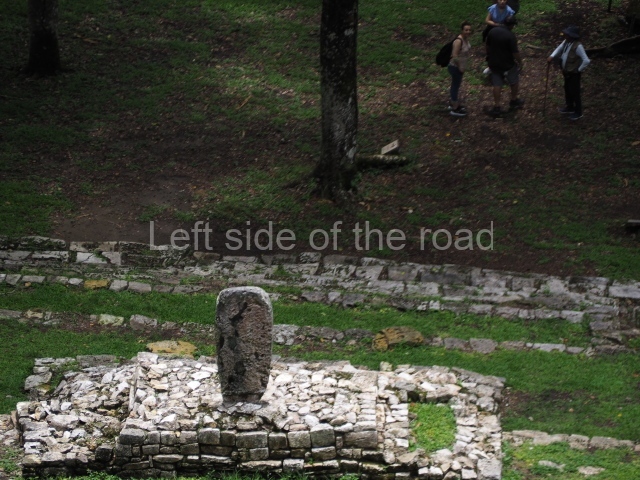

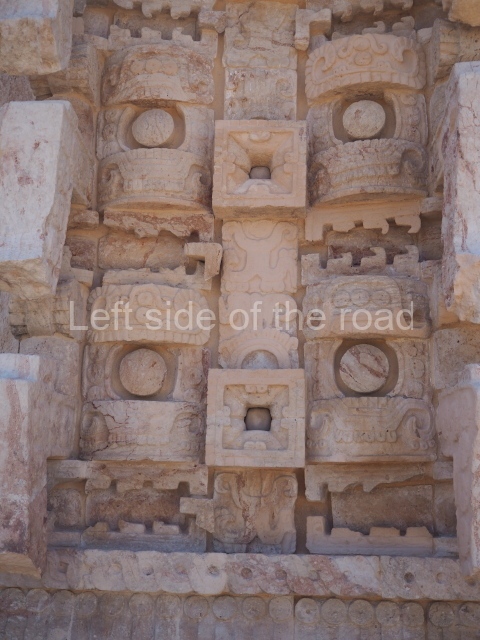

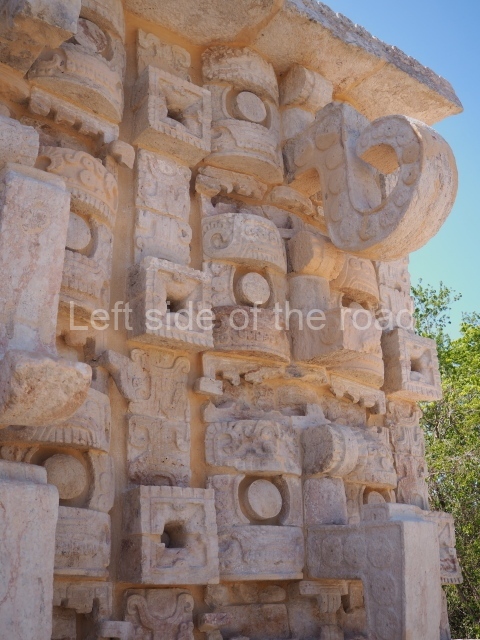

Structure 33.

This is the most important building at Yaxchilan and has attracted visitors ever since it was completed during the reign of Itzamnaaj Balam II’s son, Yaxun Balam IV. Restored and consolidated by the INAH in 1975, the group to which it now belongs also includes Structure 9, situated in the Central Plaza, stelae 27, 1, 2 and 31, and the sculptures around Stela 1. The building was a place of worship for many years after it was abandoned during the 9th century. At the end of the 19th century, Maler reported large quantities of copal near the building, the product of activities conducted by groups of Lacondon people. Maler also lived at the building during his sojourn at the site. When the city was occupied, the roof comb of this building must have been a landmark for travellers sailing up the river or journeying from Yaxchilan. The stairway is 13.5 m wide and Stela 2 is situated on a small 2-metre terrace belonging to the Central Plaza. As one climbs up the central stairway, different parts of the building appear before the visitor’s eyes, such as the two lateral structures to the left. The great stairway leads to a small plaza measuring 30×15 m. Approximately 5 m from the central entrance to the building, a pit created during the 1975 excavations reveals another level of the earlier plaza. Situated inside the pit is a carved stalactite (Stela 31). Behind the stela is a small 2-metre-high platform leading to the hieroglyphic steps (Hieroglyphic Stairway 2) that constitutes a platform for the building. Ten of the steps mention members of the ruling family playing ball. Three show female figures holding sceptres shaped like supernatural creatures (K God). The room in the middle of the building is accessed via three doorways. The facade is articulated around three spaces: the main section, the frieze and the roof comb. The walls in the main section are very simple. Maler reported a red band running along the facade beneath the cornice and around the doorways, although nowadays there are no traces of this. At the top of the main section we see a cornice that projects some 40 cm from the plane of the wall, forming a surface from which rises a sloping plane that once displayed stucco figures in relief, which formed the frieze. Above each doorway we see a niche, aligned with the frieze. Along the lower part of the frieze is a stone frame which once supported a stucco figure, probably serving as a type of throne for a seated dignitary. Above the frame we see parts of the stucco human figures in the niche over the central and right doorways, and the remains of a seated figure in the niche above the left doorway. The roof comb comprises eight rows of stone that create a variety of tiny openings, probably designed to accommodate stucco figures. At the centre of the roof comb we see the remains of a large figure, seated and wearing a grand headdress. The three doorways display carved lintels (1, 2 and 3) and lead to a vaulted gallery. In the middle of the chamber are the remains of a seated sculpture; his head and headdress were removed from the main figure and now lie near the statue. The height of this figure with the now removed head is 2 m. On the wall near the lower part of the figure are four columns with glyphs, nowadays greatly eroded, which must have identified the individual represented on the monument. It is only possible to distinguish one title: ‘He of the 20 Captives’, one of the titles used by Yaxun Balam IV. Building 33 was probably finished by his son, Chel Te’ Chan K’inich, as a tribute to the father. Each of the three lintels that decorate the entrance show Yaxun Balam IV performing a ritual dance. Lintel 2 shows the same figure as a child, being assigned a series of royal titles, including the emblem glyph of Yaxchilan. In the 1970s Garcia Moll found the remains of a tomb with an extremely rich offering underneath Building 33, although the identity of the individual has yet to be established.

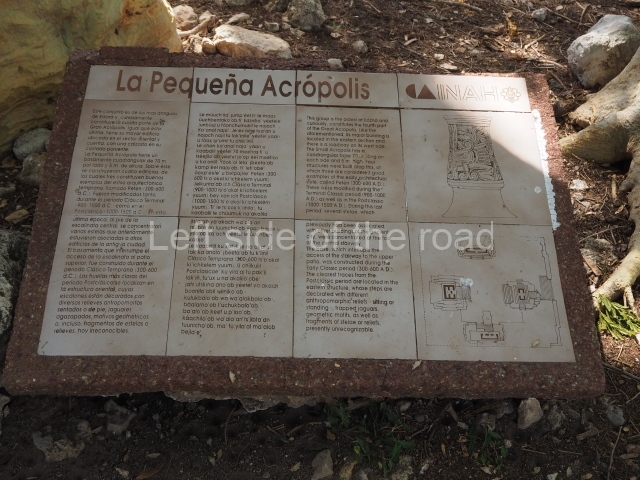

South Acropolis (Structures 39, 40 and 41).

The entrance to this complex is via the rear part of Building 33, following the path that leads to Structure 34, past buildings 38 and 37 and up to the top of the hill. This is the present-day route, but in pre-Hispanic times access must have been via a stairway behind Structure 1, leading to the front of Structure 41. A long platform in front of Structure 39 served as a base for Stela 10. The building rises from a seven-tier platform. Three doorways near the centre of the facade generate a dark interior space. Nowadays, most of the decoration, divided into three sections, has been lost. None of the stucco sculptures on the frieze have survived, although a few geometric designs are discernible at the top. Structure 39 was discovered by Maler in 1897. Stela 10 was found in situ at the time of the discovery but is now on display in the National Museum of Anthropology. Opposite the stela stood Altar 6, and altars 5 and 4 not far away. All of them still occupy their original position, although their carvings have disappeared completely.

Structure 40.

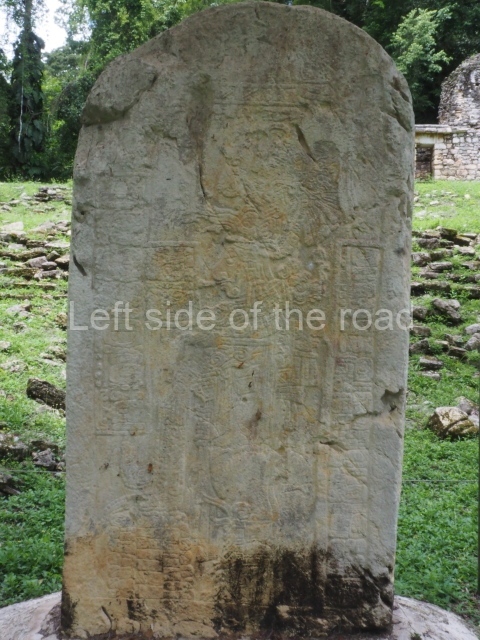

This is the central building in the South Acropolis. It was probably the second one to be constructed, after Building 39. It consists of two platforms rising directly from the level of the plaza. The associated monuments were aligned with the centre of the main facade. Altar 14 actually occupied the central doorway, while Stela 11 stood further back, but in a straight line, on the first platform. Altar 12 was situated on the left, accompanied by Altar 13, and to the right of the latter was Altar 15. Like most of the buildings at Yaxchilan, the central facade was divided into three sections: a section devoid of all decoration, covered in a simple white stucco, followed by a richly decorated frieze with stucco figures, now lost, and an ornate roof comb with stucco figures in relief. The interior consists of a dark, vaulted chamber whose rear wall displays the remains of three small stucco figures. There are also traces of polychrome paint on the walls. Maler reported ‘leaves, volutes, flowers interspersed here and there’. The colours reported by Maler are light and dark red, light and dark blue, different shades of yellow, coffee, white and green. Most of this mural has disappeared over the last century. Maler also reported having found Stela 11 in situ opposite Structure 40 in 1897. In 1964 this piece was removed along with 19 other stelae for transportation to the National Museum of Anthropology and History. However, due to its size, it could not be transported by air to its final destination and was returned by river to Yaxchilan, where it was placed on the banks of the river near Structure 5, its present-day location. Maler found two fragments from Stela 12 inside Structure 40 and a third fragment just south of the main facade, in what is thought it have been its original position. The stela has been restored and placed in front of the building’s main facade. In 1900 Maler discovered Stela 13 on the central terrace, situated north-west of Stela 11. It was consolidated by the INAH and put back in its original position in front of the building. Stela 11 was probably one of the first stelae commissioned by Yaxun Balam IV in 741, commemorating the first year {tun) of his accession to the throne. It celebrates his enthronement as an event carried out after a long series of ceremonies, including one to commemorate the death of his father Itzamnaaj Balam II.

Structure 41.

During the pre-Hispanic period, the main entrance to the South Acropolis must have led directly to Building 41. In 755, the year of its construction, the city’s inhabitants would have climbed up a great stairway and been confronted by three imposing stelae, each showing Shield Jaguar (Itzamnaaj Balam II) in military garb, humiliating a prisoner. Situated on a terrace 1.5 m higher up were two additional, albeit smaller stelae. Visible on the right are structures 40 and 39. Along the facade, a series of architectural elements form two parallel walls 1.5 m high with a cornice providing the support for the seated stucco figure of a dignitary. A band of stucco glyphs formed an inscription underneath the cornice on all four sides of the building. The frieze was decorated with zoomorphic masks and its surface was prolonged by a roof comb that projected the composition upwards to the sky. The structure was consolidated in 1979 by the archaeologist Roberto Garcia Moll (INAH). The building reveals two construction phases, like the platforms on which it stands. Stela 15 was discovered In 1900 by Maler. On falling to the ground it split into two pieces. One contained the image of the captive Ah Ahaual and the other section is on display in the National Museum of Anthropology and History. Stela 16, also found by Maler on the first terrace, again broke as it fell to the ground. It shows a figure holding a stick, with his head in profile. Unfortunately, this stela has been lost. Maler found Stela 18 laying on the lower part of the terrace from which the building rises. It had broken into four pieces. Stela 19 was found in numerous pieces and has never been reconstructed.

West or small acropolis.

This is accessed via a short path that commences just 200 m from the copper hut at the main entrance to the site and then veers right. The climb is a steep one but nevertheless worthwhile for the view of the buildings and the river from top. Excavated by the INAH at the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, it comprises two important buildings:

Temple 44.

This was dedicated in 732 by Yaxun Balam IV to commemorate his military victories and reveals details of the revival of Yaxchilan as an important power in the region. Its main facade faces north to north-east. The building is composed of a single vaulted chamber, divided by a lateral wall. Maudslay was the first person to record and photograph it with the associated monuments. In 1931 Carl Ruppert excavated the entire main facade and in addition to the lintels mentioned by Maudslay found two carved steps. There are at least six stelae that may have been associated with Temple 44 during the pre-Hispanic period (stelae 14, 17, 21, 22, 23 and 29). All of them were reported by the 14th mission to Central America conducted by the Carnegie Foundation in 1931. Stela 14 was found in six pieces on the slope in front of the building’s main facade, along with stelae 17 and 21. Structure 44 was built and the inscriptions carved to exalt the military prowess of Yaxun Balam IV. The lintels and hieroglyphic steps emphasise the victories of the king and his ancestors. This emphasis on acts of war and the absence of references to important dates in the ritual calendar lend Temple 44 a different status from Building 23, whose texts emphasise Lady Xoc’s sacrificial acts and the corresponding astronomical associations, and from Building 41, which emphasises the ritual dates associated with important acts of war rather than the acts themselves. Each of the three doorways on the main facade is decorated with a carved lintel and two steps with carved texts. The texts narrate a series of consecutive events in which Itzamnaaj Bahlam is the victor of various battles between AD 681 and 732. The events begin with the capture of Aj Nik, which occurred before his enthronement as ruler of Yaxchilan. That Itzamnaaj Bahlam attached great importance to this capture is revealed by the fact that he adopted ‘Captor of Aj Nik’ as one of his titles for the rest of his life. However, we do know that the prisoner was not a high-ranking individual in the political context of the region, but a lesser nobleman from a small site, such as Maan or Namaan, near Yaxchilan. The second prisoner mentioned is Aj Kan Usja, lord of the unidentified site of Baktun, in 713. These events are also described in the texts on the stelae in front of Building 41 in the South Acropolis.

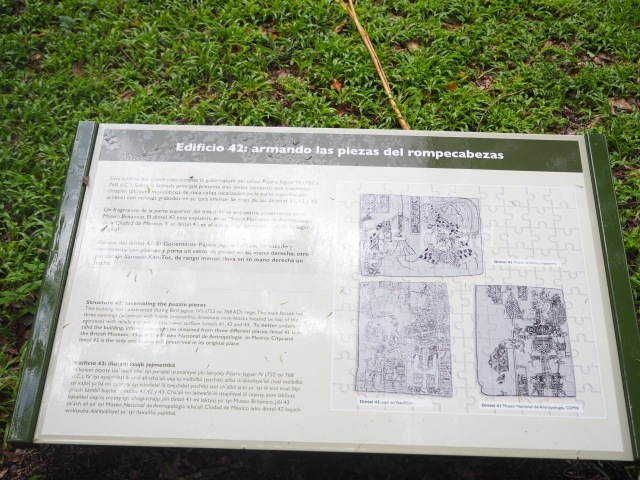

Temple 42.

This building has three doorways, each with a lintel, and two hieroglyphic steps that narrate important aspects of the life of Yaxun Balam IV (lintels 41, 42 and 43). It was restored in 1982 by the INAH. The upper part of Lintel 41 was first reported by Maudslay who sent it to the British Museum, where it remains on display. Its lower part was found in 1931 and restored to its original position. In 1889 Maudslay photographed Stela 42 and a copy was made. Nowadays, it can be viewed in situ. Stela 43 was recovered by the INAH and sent to Mexico City in 1964. Nowadays, it is on display in the Maya Room of the Museum of Anthropology and History.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp160-171.

1. The Main Plaza; 2. Hieroglyphic Stairway; 3. Ball Court; 4. Structure 1; 5. Structure 3; 6. Structure 20; 7. Structure 21; 8. Structure 22; 9. Structures 23 and 24; 10. Central Acropolis; 11. Structure 33; 12. South Acropolis; 13. Structure 40; 14. Structure 41; 15. West Acropolis; 16. Temple 44; 17. Temple 42; 18. South-east group.

Getting there;

It is possible to get to Frontera Corozal by combi from Palenque but to visit the site and then return the same day might be problematic. There is accommodation at Frontera but some of it will be very expensive. The other issue is negotiating a launch to take you the 30 minutes down river (and then back again). Guide books say try to join a group but most of the groups are those organised by tour companies and the chances of getting on any of their launch is minimal. This is where taking an organised tour makes sense (which would normally be combined with a visit to Bonampak). The costs and hassle of doing this yourself outweighs the extra cost.

Entrance:

This, for me, was all part of the tour cost.