Tulum – Quintana Roo

Location

Built on a clifftop on the shores on the Caribbean Sea and surrounded by mangroves and sand dunes, Tulum is situated 131 km south of Cancun on federal road 307 between Puerto Juarez and Chetumal. Tulum was the name given to the city in 19th century and it means ‘wall’ or ‘palisade’, a reference to the defensive wall that surrounds it on three sides. According to 16th-century sources, the original pre-Hispanic name appears to have been Zama (‘dawn’).

History of the explorations

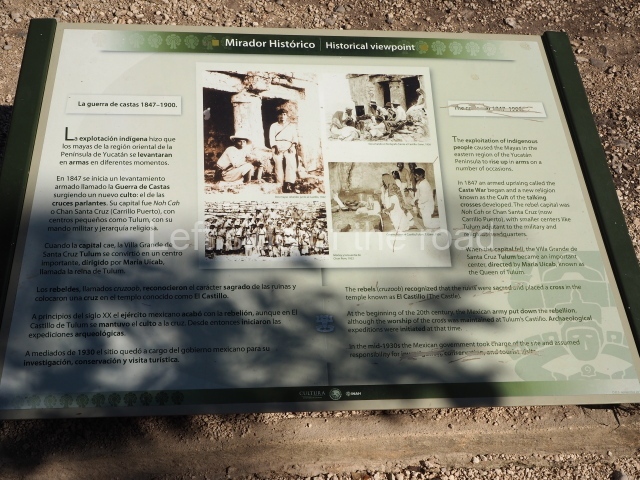

The first reference to Tulum was probably made by Juan Diaz, the chronicler of Juan de Grijalva’s expedition, as they sailed along the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula in 1518. In his account, he recalls having seen a city as large as Seville. In 1579, in his Relaciones de Yucatan, Juan de Reigosa refers to Zama as a walled city in ruins. At the beginning of the Caste War in 1847, Tulum lay in rebel territory and by 1871 had become one of the sanctuaries for the worship of the ‘talking crosses’, with Maria Uicab as the main priestess.

Pre-Hispanic history

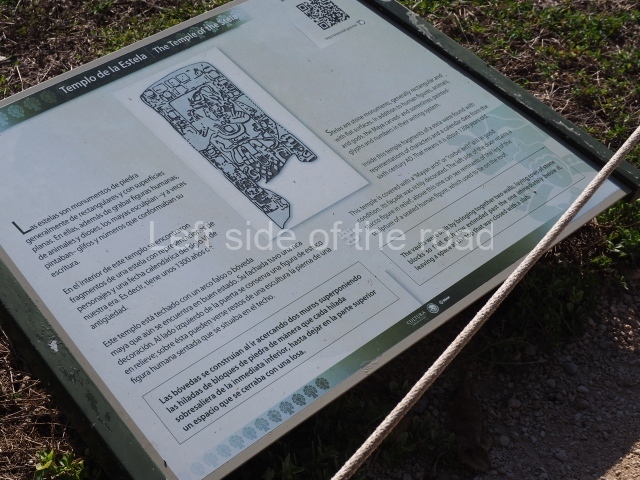

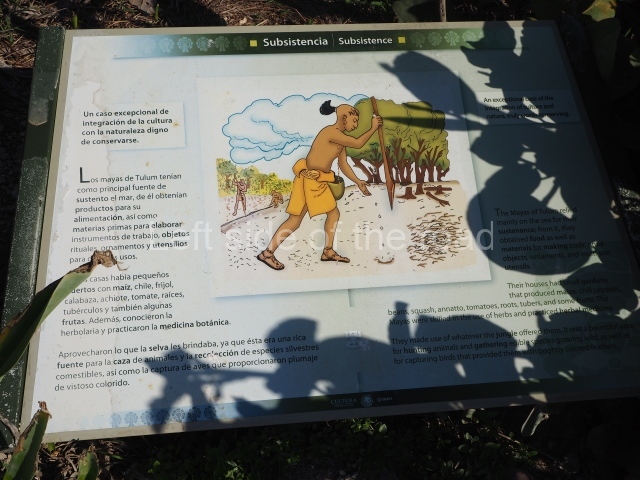

Tulum is the most representative site of the East Coast architectural style. Although it was built between AD 1200 and 1550, it contains elements such as Stela 1 (AD 564) and Structure 59 with architectural characteristics from the Classic era, which suggest an earlier occupation. Tulum is regarded as one of the principal Maya cities of the 13th and 14th centuries, during which time it was a key site on the trade route and a strategic location for exploiting the rich marine resources of the eastern Yucatan coast. Because of its strategic location, some researchers believe that during its peak Tulum must have been an important nexus between the maritime and terrestrial trade of the Yucatan Peninsula. It is also thought to have enjoyed political independence from other provinces until the arrival of the Spaniards and its subsequent abandonment in the 16th century. Some of the architectural characteristics observed at Tulum denote influences from other regions in both the Maya area and Mesoamerica. For example, there are reminiscences of Toltec elements like the ones found at Mayapan and Chichén Itzá, most notably the use of serpent columns. Similarly, although the style of the murals on the buildings has Maya iconographic elements, it is nevertheless very similar to the Mixteca codices from the central plateau.

Site description

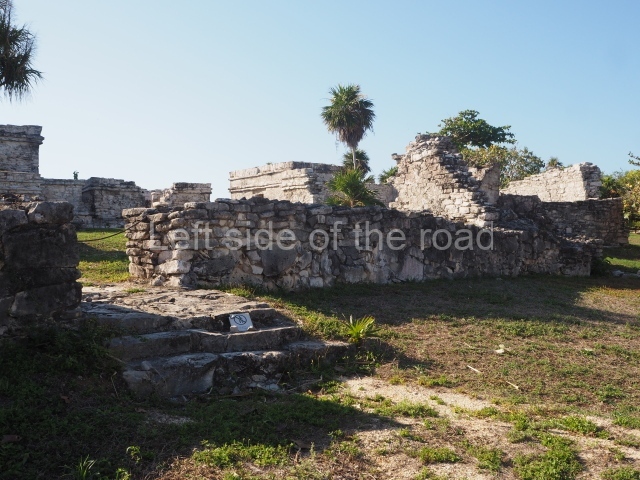

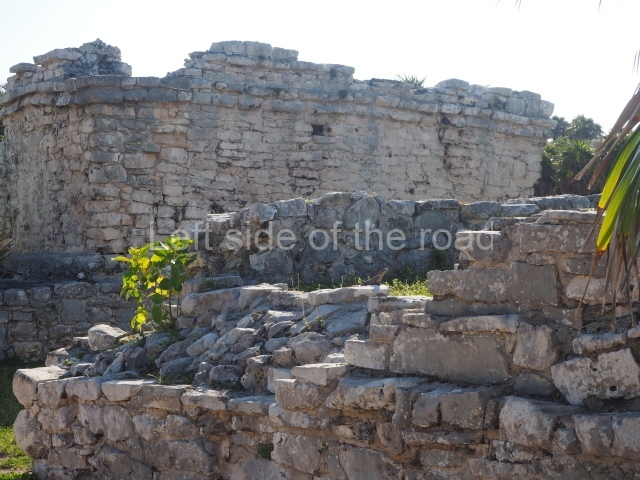

The ruins of the ancient city of Tulum are scattered on a band of some 6 km along the coast and include the core area as well as the simple wood and palm dwellings of the ordinary citizens. The core area is approximately 400 m long and 170 m wide, and is surrounded by a fortified wall on three sides; the fourth side is a cliff overlooking the sea, which provided natural protection. The walled enclosure displays a certain urban layout of its buildings and is crossed from north to south by a causeway. In addition to is defensive function, the fortified wall also turned Tulum into something of a sacred precinct with restricted access. This large wall may well have stood over 4 m high and its five vaulted gateways are still visible today: two on the north side, two on the south side and one in the middle. There are also two watchtowers at the north-west and south-west corners.

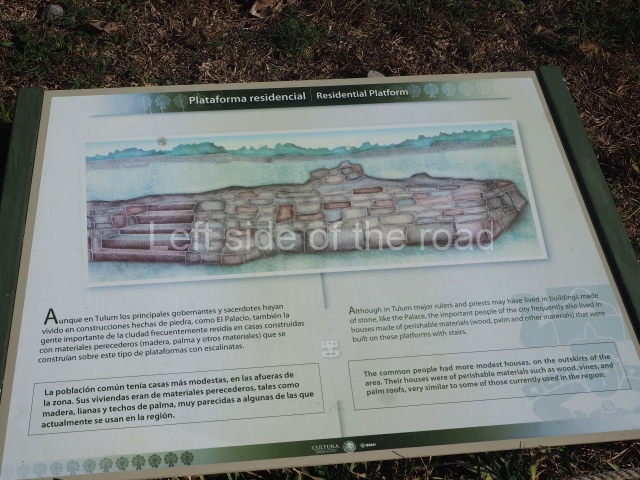

Interior precinct.

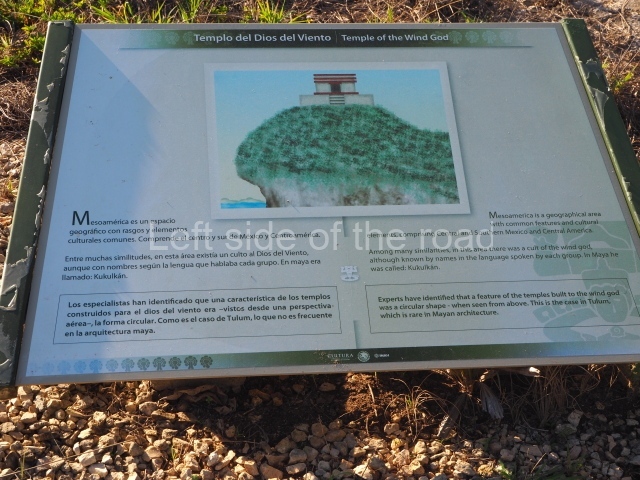

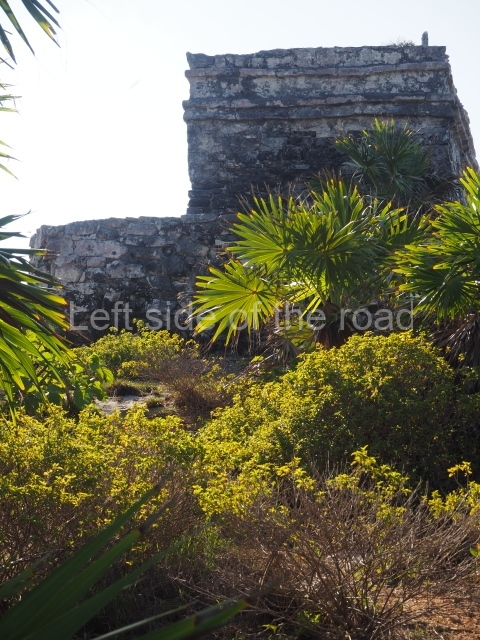

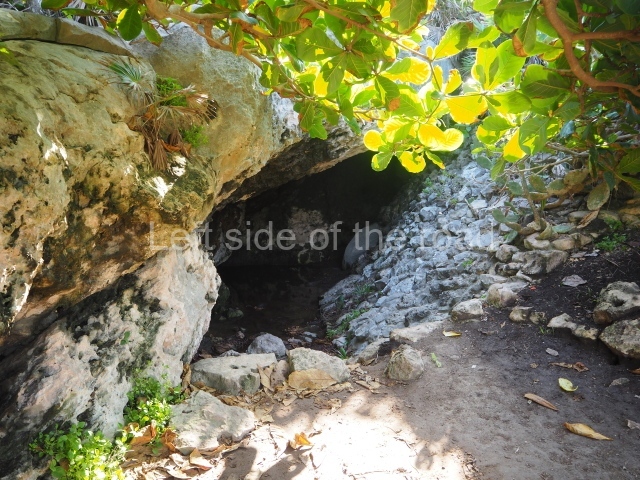

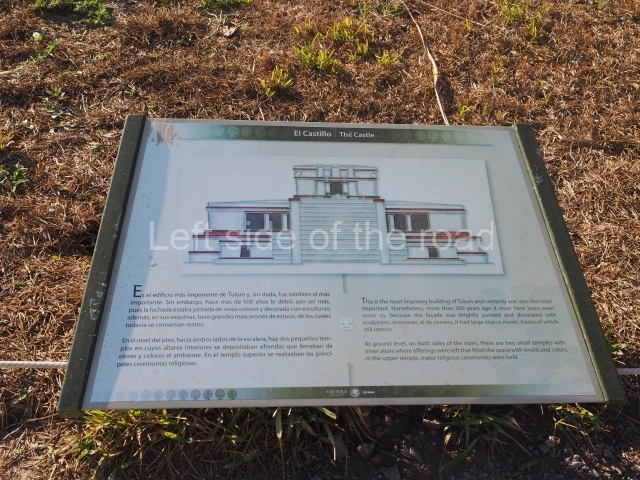

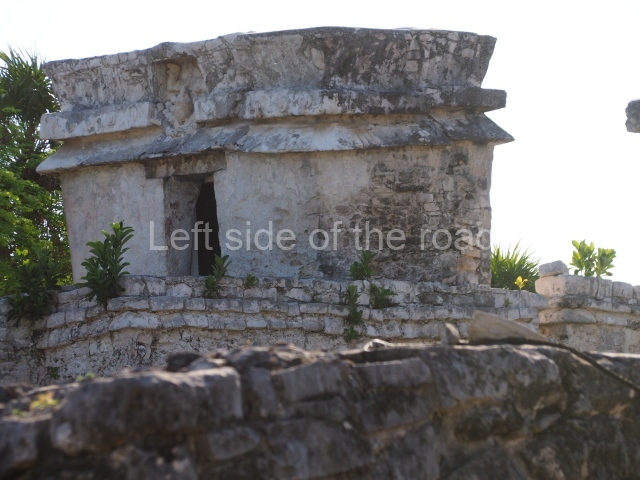

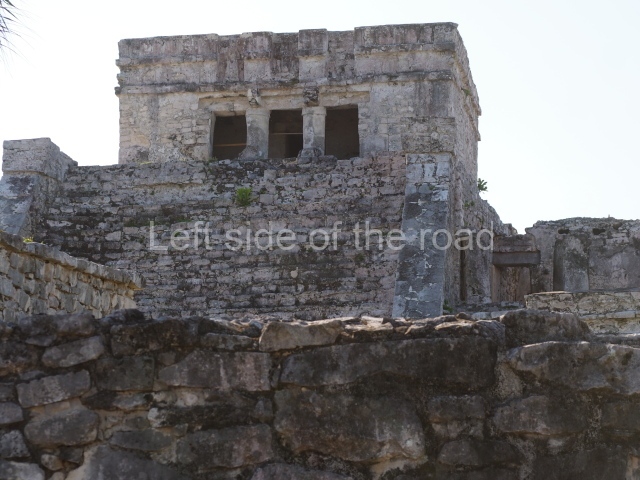

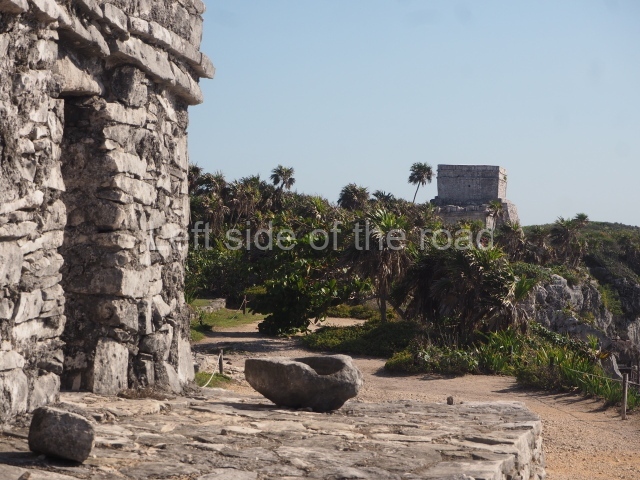

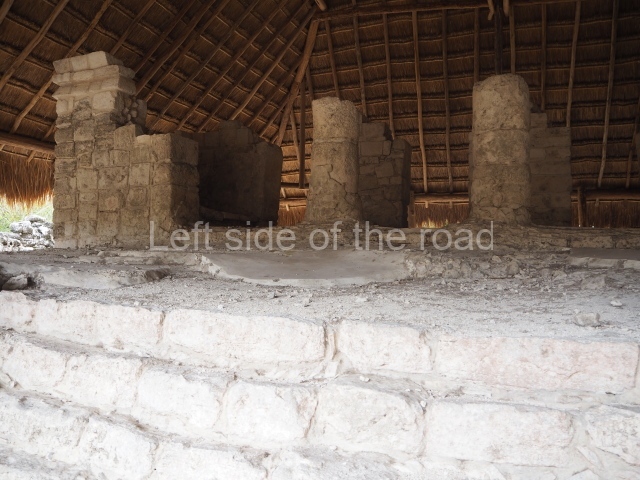

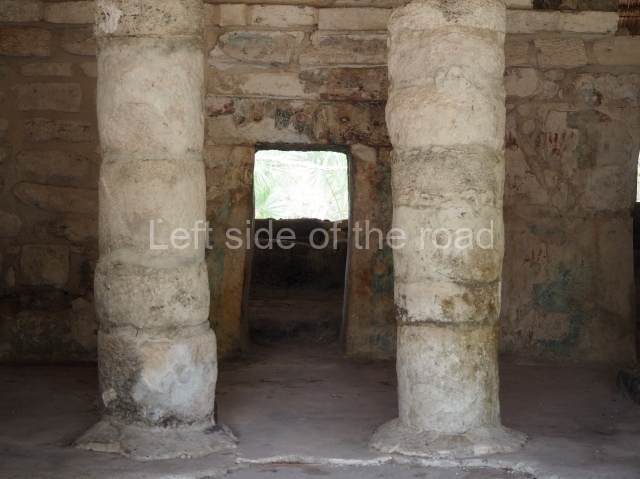

This is the name of the group of 12 buildings surrounded by a second, albeit smaller, defensive wall that restricted access. Inside this area is the Castillo, the most important building at Tulum, built with its back to the sea on the highest part of the cliff. The product of several construction stages, it is higher and larger than any of the other buildings at the site. A wide stairway with balustrades leads to the temple at the top, which contains two room accessed via three serpent columns. The façade displays two zoomorphic masks at the corners and three niches, the middle one of which contains the figure of a diving god. Flanking the stairway are two adoratoriums and at the foot of it a platform that was probably used for dance rituals. Another important building in this group is the Temple of the Initial Series, where the earliest date thus far recorded for Tulum was found. Also of great importance is the Temple of the Diving God, which is composed of a platform and a single-room building with interior benches. This temple is a good example of the ‘fallen wall’ characteristics of the architecture from this period. The main façade and the interior still display traces of paint, and the former a niche with a diving god. Flanking the causeway or main path in Tulum are a series of primarily residential constructions, such as the house of the columns, an L-shaped building with a large interior and a colonnaded entrance that once supported a flat roof. Another interesting example is the palace of the halachuinic, ‘great lord’, with a portico, three rooms and shrine within. The façade of this building also displays a niche with an image of the diving god and traces of the original paint. In the centre of the city, almost opposite the Castillo, stands the Temple of the Frescoes, one of the most interesting buildings in the Maya area in terms of its pictorial representations. It is the product of several construction phases; the original building was a room with an altar and richly painted walls, and a diving god in the central niche on the façade. It subsequently gained a portico or gallery on three of its sides, which is the construction we see today; it has four columns at the front and two pilasters to the south, flanking the entrance. The main façade contains three niches with representations of the diving god and figures with feathered headdresses. At every corner of the building is a giant mask of the god Itzamna, the lord creator of all things. The small temple on the roof of this building corresponds to the final stage of construction. The paintings inside make reference to different gods, mainly associated with farming and the underworld. In front of it stands Stela 2, nowadays greatly eroded but which once displayed the profile of a dignitary wearing a bird headdress. Situated opposite the former building is the House of the Chultun, a residential construction. The three entrances, defined by columns, lead to a large interior space which once had a flat roof made of wooden beams and lime concrete. Like most the buildings at Tulum, the façade displays a diving god. At the south-west corner of the building we can see a chultun, a type of cistern for collecting rainwater, from which the house takes its name. Situated in the northern section of the settlement are the House of the North-west and the House of the Cenote, as well as various adoratoriums near the coast the temple of the wind god. The former construction has three entrances flanked by columns, while the House of the Cenote stands on the natural vaulted roof of a cenote and also has three colonnaded entrances. Both constructions are thought to have served as family tombs. The Temple of the Wind God stands on a natural elevation at the edge of the cliff. Its semi-circular platform and the small altar inside suggest that it may have been dedicated to the wind god. Six small adoratoriums are situated to the north-east, so tiny that they must have fulfilled some religious function. Finally, situated at the south-east corner of the city is a group of elite residences.

Jose Manuel Ochoa Rodriguez

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp445-447

Further Information:

How to get there:

From Tulum town. The entrance to the site is about 3 kilometres from the centre of the modern tourist town of Tulum. You might want to consider hiring a bike for the visit. The actual entrance to the site is a long way from the entrance on the main road, having first to pass what sounds like an horrendous ‘theme park’ and then you have to run the gauntlet of a huge shopping and eating complex. A bike will allow you to pass quickly through all this tat.

GPS:

20d 12′ 52″ N

87d 25′ 44″ W

Entrance:

First there’s a charge of M$58 to enter the ‘biosphere’. This at a control on the approach road to the site. Then it’s M$90 to actually enter Tulum ruins.

It starts to get busy very soon after opening (at 08.00) and by 09.00 small guided groups start to arrive which soon make the small and quite compact site feel crowded.