Calakmul – Campeche

Location

The site lies 155 km from Escarcega. Take Federal Road 261 to Conhuas and then, a few kilometres further on, the turn-off to Calakmul in the south. On this road there is a toll to enter the Biosphere Reserve and another one to enter the archaeological area. The journey from Campeche is approximately 310 km. This major Maya city is situated inside the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve. The Calakmul archaeological area was declared a UNESCO world heritage site in 1999. The name is a neologism composed of Yucatec Maya words meaning ‘mounds together’ or ‘mounds adjacent’. The name is a reference to the largest structures on the site, visible from the air or a distance as two great protruberances looming above the surrounding green landscape.

Timeline, site description and monuments

The earliest evidence of the site dates from the Late Preclassic, several centuries before the Common Era. The city reached its peak between the 6th and 8th centuries AD, before gradually losing its political influence and population, which migrated to other places. During the Postclassic, Calakmul was occasionally visited by pilgrims bearing offerings in recognition of its former glory.

Great plaza.

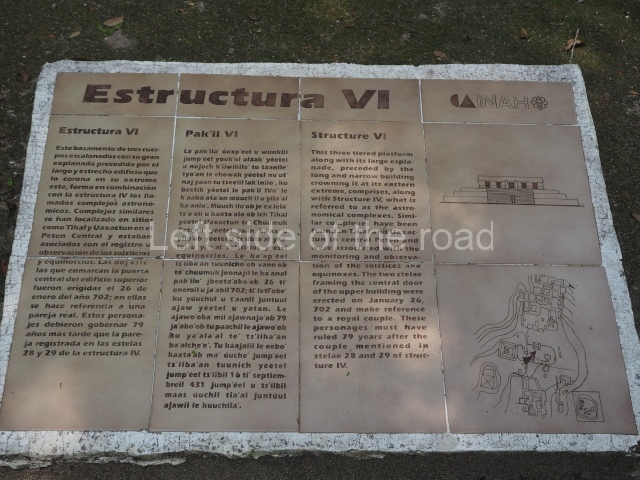

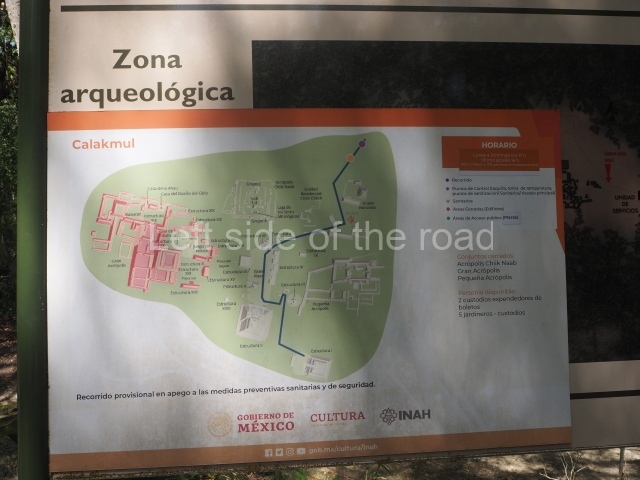

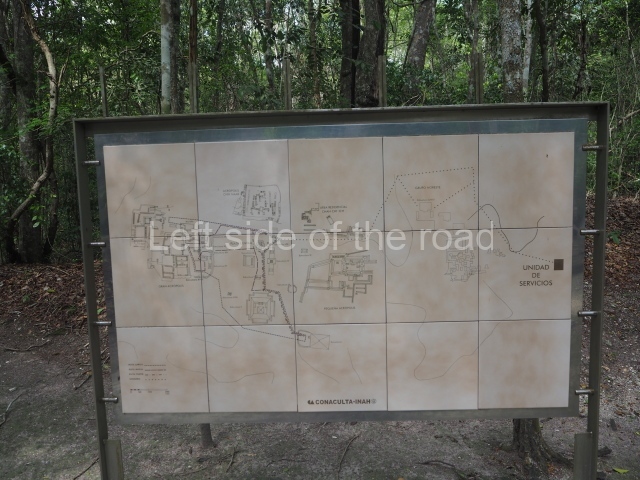

The tour of this site begins at the heart of the ancient metropolis. This plaza is 200 m long (north-south) and 60 m wide, and is delimited by Structures IV (east), II (south), VI (west) and VII (north). Structure V stands inside the plaza. Buildings IV and VI form a single structure used for astronomical observations, especially at the solstices and equinoxes. Building V is surrounded by 12 stelae that record important events in the life of various 7th-century-AD rulers, which suggest that it was used for the ritual celebration of commemorative ceremonies. Building VII measures approximately 40×47 m at its base, has an average height of 25 m and is surmounted by a shrine with three parallel rooms. The excavations uncovered the first tomb and grave goods of one of the Calakmul rulers, Yuknoom Took Kawiil, who was buried around AD 735. His jadeite mosaic mask, with its shell and obsidian eyes, became an emblem of the site.

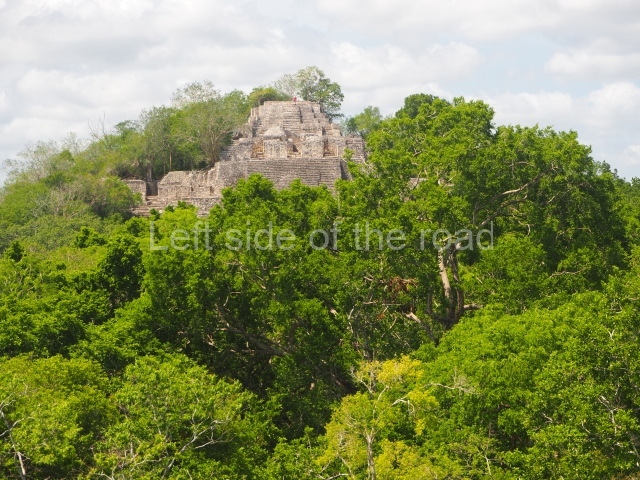

Structure II.

This is an enormous pyramid platform measuring approximately 140 m around the base and 50 m in height. It contains several sub-structures, having been added to over the course of 10 centuries to become the highest and largest construction on the site. At its base is a group of stelae dating from the AD 702 to 731. These are followed by several buildings and then three stairways, two at the sides and one in the middle. Flanking the latter stairway are the remains of four giant anthropomorphic masks, whose stucco cladding has now been lost. Two thirds of the way up is another tier, on which stands a large room with three entrances. The pyramid continues after this, again with three stairways, culminating in a flat section where a great temple must once have stood. Excavations inside Structure II have dated the earliest construction phase to the Late Preclassic (250 BC-AD 100). It contains a platform 107 m long (north-south), 75 m wide and approximately 8 m high, on which stood several buildings, all of them approximately 5 m high. One of them acted as the entrance to the inner precinct and its frieze still displays a stucco mythical allegory: two supernatural birds with human faces accompany a deity, possibly the rain god, who descends or advances towards the building entrance. The scene is covered and framed by a light blue band at the ends of which we see the head of a crocodile, the Celestial Monster. This representation has iconographical connections with monuments at Izapa, Takalik Abaj and Nakbe. Another later construction hidden inside Structure II revealed the tomb of the ruler known as Fire Claw (Yuknoom Yichaak Kahk), who was wrapped in a shroud, placed on a wooden dais and accompanied by rich grave goods comprising pieces of jade, ceramic, shell, feathers, stucco and jaguar claws.

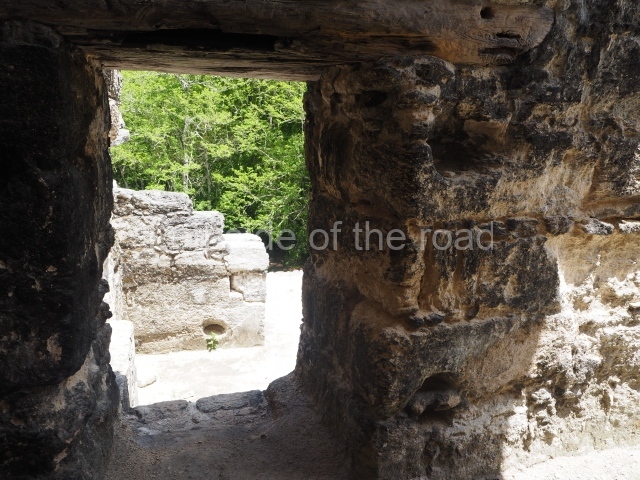

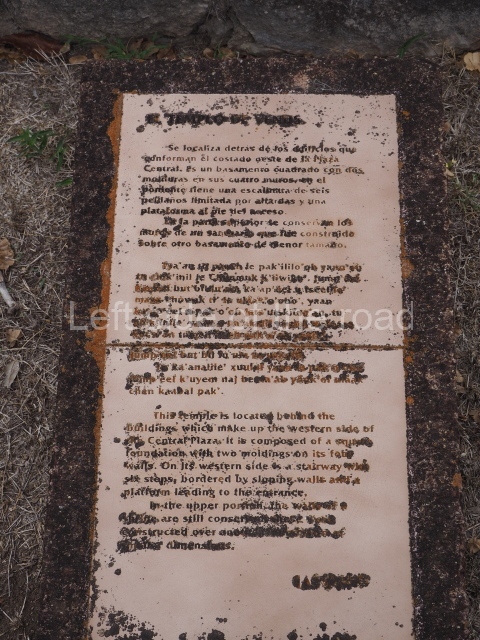

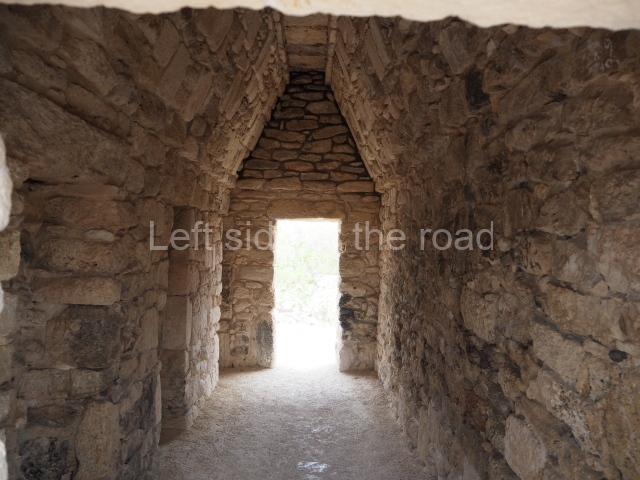

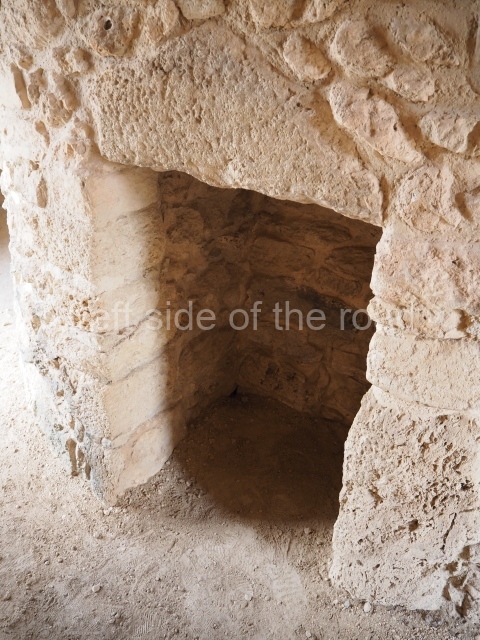

Structure III.

Situated 50 m north-east of Structure II, this was an elite dwelling with a broad stairway on its west side leading to 12 rooms. It is further enhanced by a platform 36 m long (north-south), 32 m wide and 5 m high. Both its architecture and narrow interior spaces confirm that it was built during the Early Classic, perhaps between AD 370 and 400. Some of the rooms had small windows and holes in the jambstones to hang curtains. The excavations also revealed a rich burial with three jadeite mosaic masks, one for the face and the others for the waist or breast, jadeite necklaces, shells, pearls, a stingray spine and a number of vessels. The remains of a piece of wood covered with stucco were also found.

Structure I

To the south of Structures II and III a path leads to the second-highest pyramid platform at Calakmul, measuring 100 m along each side and 40 m in height. Its main facade faces west and at its base and on several levels there are various stelae, some of which were mutilated in the mid-20th century. Fortunately, at the foot of the structure it is still possible to see three large monolithic altars forming a triangle; these symbolise the Uxte Tuuri (literally, Three Stones) or ‘primordial hearth’, one of the ancient names for Calakmul. At the top of the building is a shrine with a small room. The central stairway also appears to have been flanked by giant stucco masks; two examples were found but have been covered to preserve them.

Ball court.

Situated in the west group at Calakmul, in the section known as the Great Acropolis, is a ball court (Structure XI) of modest proportions and a north-south axis, built around AD 750 with materials recycled from a previous construction, possibly during the reign of Bolon Kawii.

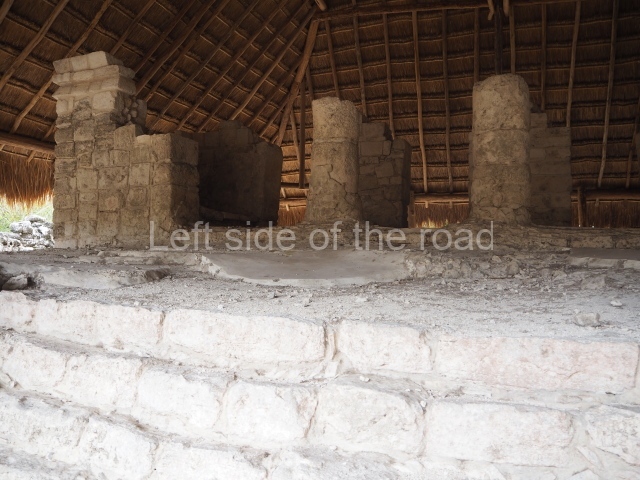

Structure XIII.

This is visible before you get to the Ball Court and is situated to the north of the latter structure. It takes the form of a pyramid platform, 43 m long and just over 8 m high. Its four tiers are fronted by a broad stairway. At the top is a two-storey building corresponding to two different construction periods. The associated stelae and altars indicate that it was built in the 8th century AD. To the west is a gallery with seven entrances formed by pilasters, erected before the platform, which now partly covers it.

Altar of the prisoners.

Just west of the Ball Court, the pre-Hispanic sculptors used an outcrop of limestone to form part of the urban design of the settlement. They gave it a semicircular shape (approximately 5 m in diameter) and carved the images of seven kneeling individuals with their hands tied, no doubt defeated in battle. Nowadays, the scene no longer visible, having been covered up to preserve it. It may have been used in the nearby Ball Court, where two teams competed and the losers were decapitated.

Structure XIV.

This stands east of the Ball Court with its main facade facing west. It contains several rooms from the 8th century AD and clearly marks the difference in height (approximately 3 m) between the east section and this structure, which was the entrance to the Great Acropolis.

Structure XV.

This is situated south of the former structure and is the product of several construction phases in the 7th century AD. The archaeological excavations revealed three funerary chambers. One of them seems to have contained the remains of the wife of Yuknoom Cheen the Great (600-686), also the mother of Fire Claw, who ruled Calakmul between 686 and 695. Her grave goods included numerous jadeite objects, shells and ceramics. The corpse was wrapped in strips of chicle or gum, which explain why it is exceptionally well preserved and also why it so fascinating to us today.

Structure XVI.

This is situated opposite the previous structure, facing west of the latter. The platform measures 100 m long (north-south) and 80 m wide, and behind it is a large courtyard with various rooms. A palatial complex with restricted access, it has only been partly excavated and to date only eight stelae have been associated with it. Some of the dates inscribed on these go back to the end of the 7th century and beginning of the 8th century AD.

Structure XVII.

We are now in the south-east section of the Great Acropolis, in a partly excavated building, approximately 50 m in length with a broad stairway leading to a two-room construction. An associated stela is inscribed with the date AD 790.

Structure XX.

This lies west of the Ball Court and the Altar of the Prisoners. It is approximately 36 m long and almost 4 m high. The excavations have uncovered evidence to suggest that this section of the Great Acropolis has a long history, commencing in the early centuries of the Common Era and with successive modifications virtually until the city was abandoned. The view from the top provides a good idea of the control exercised by the few families who had access to the Great Acropolis.

Structure XIX.

Situated north of the previous structure, this has been excavated and partly restored. It contains several rooms, some of them with benches. The main facade has a broad stairway and faces north, which suggests that it was the main entrance to the Great Acropolis from this side.

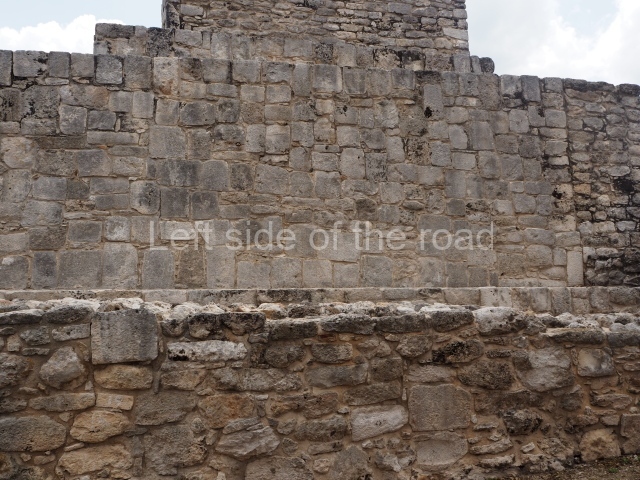

Wall.

To the north of Structure XIX a path leads to the remains of an ancient wall, just over 6 m high when viewed from the outside and approximately 2 m thick. There is no evidence to suggest that it was a defensive structure as it does not surround the core of the site. It may well have acted as a boundary for the city’s ceremonial precinct, to control access from the northern sections.

Residential units.

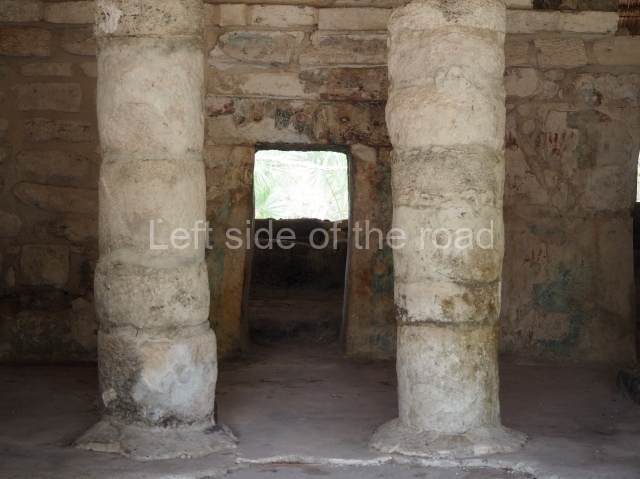

The north-east and north-west sections of the Great Acropolis offer an overview of the housing occupied by the families closest to the rulers. The unit known as the House of the Owner of the Sky (Utsial Caan) has a small open space at the centre, approximately 75×50 m, with an underground tank for rain water (chultun); its only access is via two narrow entrances on the south and west sides (the east side was open to facilitate the flow of people). The space comprises 13 rooms, many of them with benches, arranged around three interior courtyards. The entire complex was surrounded by a wall some 4 m high. A little further to the west is the residential unit known as the House of the 6th Ahau (Wac Ahau Nah), a similar but smaller complex, thus called because of the discovery of a capstone inscribed with the date 6 Ahau. This unit has a 65 sq m courtyard surrounded by eight large rooms and a smaller one, possibly a storeroom, each with its own entrance. The rooms have a surface area of between 10 and 15 sq m, mainly taken up by benches. Their occupants may have obtained water from an open tank or the aguada situated some 300 m from the Great Acropolis.

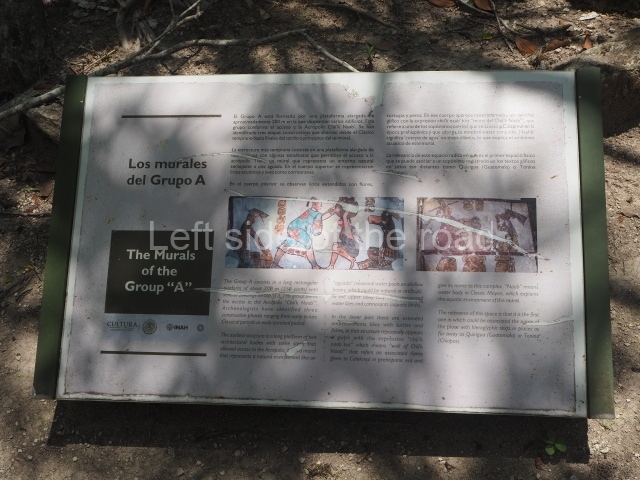

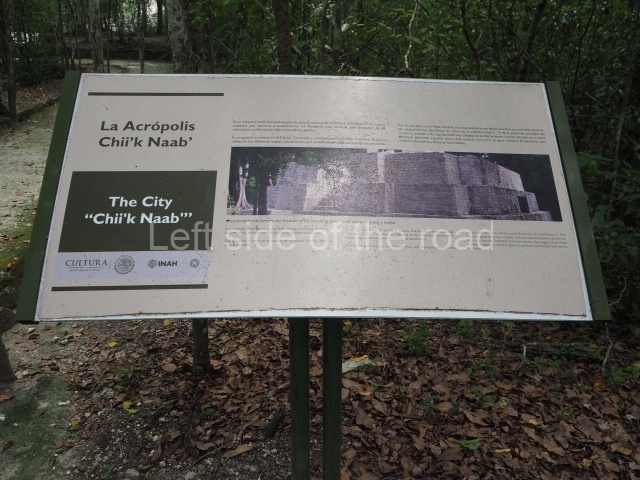

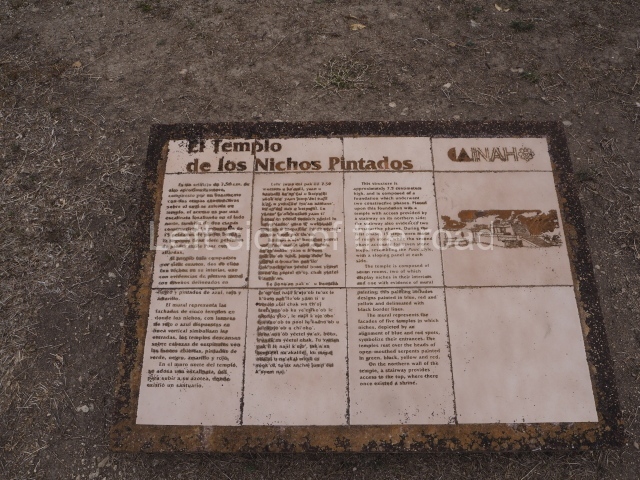

Chiik Naab acropolis.

This group of buildings lies 150 m north-west of Structure VII. Many of the buildings face the cardinal points, and all of them surround an irregular quadrangle which for a time functioned as a market. The excavations have shown that several of these buildings were actually residences. Another interesting find was a construction that seems to be half-walkway and half-bench. Over 200 m in length, it displayed traces of mural paint in the sections that had been covered by subsequent works. The motifs represented show an aquatic setting: small waves, herons, turtles, snakes, fish and water lilies. There are also large hieroglyphic cartouches inscribed with the toponym Chiik Naab or water lily, a term that appears to refer to the core area of Calakmul. In another building in the eastern section traces of mural paint were detected on a construction that had been carefully covered in ancient times. This is a small three-tier pyramid platform whose walls display various scenes in a naturalistic style, like that of many polychrome plates and vases. Different people are depicted participating in a festivity at which atole is drunk, tamales are eaten and tobacco is smoked. The associated glyphs confirm these activities. There may also be scribes and a bearer with a large cooking pot on his back. Like the vessels depicted in the paintings, the analysis of the associated ceramic materials suggest that they date from the 7th century AD. Outside the core area of Calakmul there are thousands of remains from more modest dwellings, which must have once had stone foundations and walls and roofs of perishable materials. These correspond to the population at large, the people responsible for providing water, food and labour to those of a higher social rank.

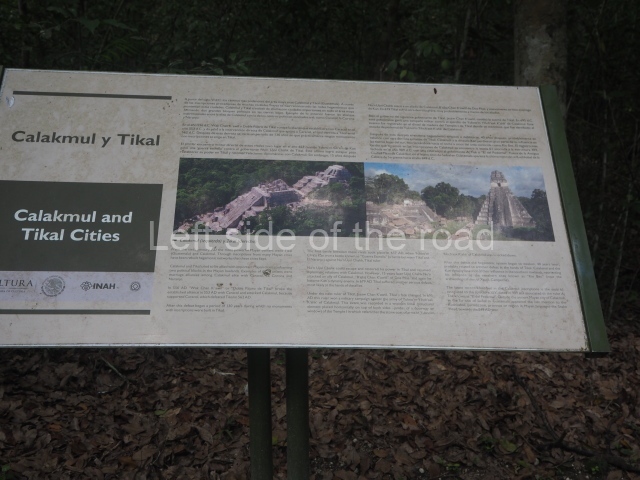

Importance and relations

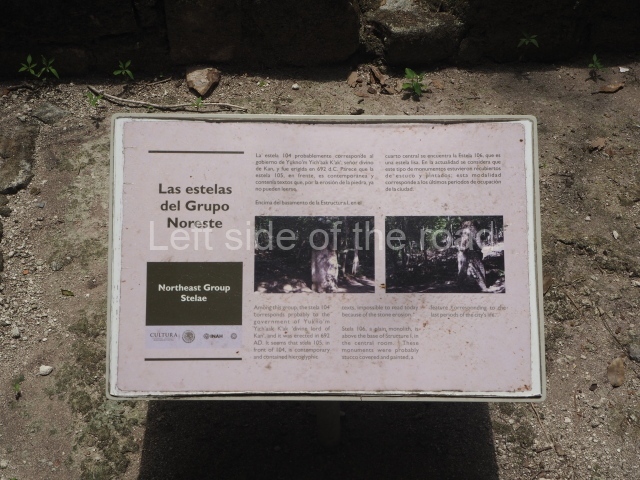

The kingdom of Kaan or the Serpent was one of the most powerful polities in the Classical period. During AD 500 to 800, it eclipsed Tikal, its great rival. Calakmul also boasted two emblem glyphs: one to denote its territorial power, Kaan, symbolised by a serpent’s head, and another to refer to the core area of the city, Chiik Naab, which means something along the lines of ‘place of the water lily’. Like the serpent and its mythical connotations, the water lily (Nymphaea ampla) is a flower typically associated with the Maya world and it had an important symbolic role, evoking the waters that provided access to the underworld. The water lily was often represented in the grave goods or the headdress of high-ranking dignitaries. The importance of Calakmul lies not only in its monumentality and vast surface area (over 30 sq km), but also in the rich history contained in its material remains. It boasts several jadeite mosaic funerary masks, vessels inscribed with hieroglyphic texts and symbolic images and mural paintings, all of which have outstanding aesthetic and cultural merits, as well as enriching our knowledge of the Maya civilisation. Calakmul is the site with the largest number of registered stelae: 117 in the year 2000. Some of them were smooth (25), others mutilated or stolen in the first half of the 20th century, and others with inscriptions and images that have enabled us to reconstruct most of the dynastic history of Calakmul and other places associated with it. Numerous vessels have been found in funerary contexts at Calakmul, as well as a variety of elements that formed part of the attire of the officials interred: jadeite masks, breastplates, ear ornaments and necklaces; pieces of shell and conches, objects made of obsidian, stucco, etc. Most of these materials are now on display in the Archaeology Museum in Campeche City.

From: ‘The Maya: an architectural and landscape guide’, produced jointly by the Junta de Andulacia and the Universidad Autonoma de Mexico, 2010, pp339-344.

1. Central Plaza; 2. Structure II; 3. Structure III; 4. Structure I; 5. East Group; 6. Great Acropolis; 7. Ball Court; 8. West Group; 9. Acropolis Chiik Naab.

Getting there:

There is basically no way you can get to Calakmul either without your own transport or by taking one of the many versions of an organised tour. There are presently no places to stay any closer than about 60 kilometres (although a very expensive resort is in the process of being constructed – as part of the Tren Maya project).

GPS:

18d 06′ 23″ N

89d 49′ 01″ W

Entrance:

M$270 – the combined cost of entrance to the National Park and entrance to the archaeological site, paid in two parts, the first just off the main road 60 kilometres from the site, the second at the site itself.