Arch of Drashovice – Introduction and Statue

A journey along the valley of the Shushicë River is interesting under any circumstances, the road is rough in places (most places) but the view of the mountains and the countryside is astounding and makes the effort worth it. When you add the Arch of Drashovice 1920-1943 it’s almost an obligation.

The Drashovice arch is truly a monumental monument. It attempts to tell a story of two important battles that took place in almost the same location, separated by a period of 23 years, both of which significant in the struggle for the national liberation of the Albanian people.

The monthly political and informative review, Albania Today, published monthly from the end of 1971 until the end of 1990, described the monument thus, reporting a visit that Enver Hoxha made to the region in the beginning of 1981:

The moments of Comrade Enver Hoxha’s visit to the monument ‘Drashovice 1920-1943’ were very moving. This monument, the work of the People’s Sculptor Muntaz Dhrami and the architects Klement Kolaneci and Petrit Hazbiu, is erected in memory of two battles waged in different historical periods in the same place – in Drashovice. It is devoted to the legendary epic of the war of the Albanian people in 1920 for the liberation of Vlora from the Italian occupiers, and another legendary battle which took place in September 1943 after the capitulation of fascist Italy, and in which the partisan forces, led by the People’s Hero Hysni Kapo, routed the German invaders who replaced the Italian troops. The battle went on for more than 20 days and ended in a great victory for the partisan forces.

The monument, which was put up last year, is a work of art which will perpetuate in the centuries the unconquerable strength of the Albanian people in their struggles against the enemy, and their heroism in their legendary wars for freedom and independence. It renders clearly the great idea that freedom is won and defended with blood. With its masterly idea-artistic solution, the monument is a success of their authors and a new contribution to the further enrichment and development of our monumental sculpture.

Albania Today, No 3, (May-June) 1981

Mumtaz Dhrami is the sculptor responsible for some of the finest examples of Socialist Realist sculptural art in the 1970s and 1980s, such as can be found in Peze and Gjirokaster. Many of his works of art have been collaborations with other sculptors but this one is only credited to him, and yet it is by far the biggest and most complex in the country. It was completed in 1980. His name and the date of inauguration can be seen at the bottom of the interior of the arch, on the right hand side.

Each half of the arch would stand as an impressive monument in itself but by bringing the two incidents together Dhrami unites the two battles as being part of the overall struggle. Separate they merely celebrate victorious battles against successive foreign invaders but together they refer to the Declaration of Independence in November 1944, the aim of Albanians over the centuries.

However, it was only under the leadership of the Communist Party that real independence was achieved and at the apex of the arch an image, in bronze, of the Albanian flag is surmounted by a star proudly declaring that reality.

All the decorated Albanian lapidars tell a story but whereas the majority are either short stories or novellas the arch at Drashovice is akin to ‘War and Peace’ with the amount taking place on all the four faces of the arch.

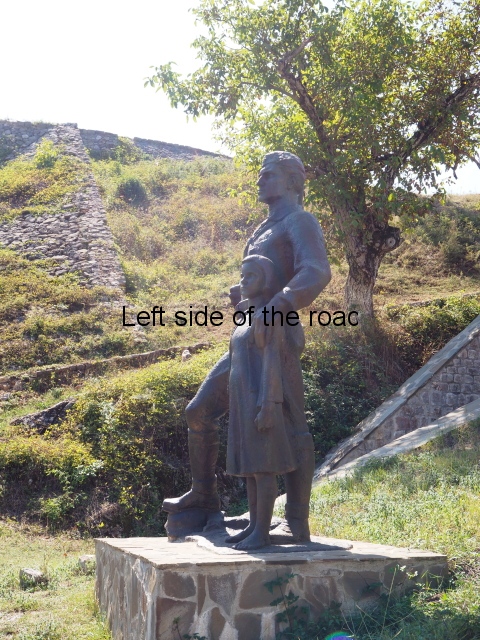

If coming from the direction of Vlora the arch is on the left side, across from the road that takes you over the bridge to the small village of Drashovice itself. There’s a small shop, with an attached bar, at the junction but little else on this side of the river. From the road there are two flights of five low steps which lead to the first element of the sculpture, the a statue, in bronze, of two fighters, one from each era.

They are depicted as if standing on a mountain, the one on the right (representing the period of the 1920s) is slightly lower than his more recent counterpart. He is dressed in the costume of a warrior from the mountains at the beginning of the 20th century, that is a qeleshe (felt hat), xhakete (jacket) with a cape, a fustanella (a skirt-like garment worn by men) and on his feet opinga, a hob-nailed sandal, turned up at the toe. Around his waist he wears an ammunition belt and has a pouch at his waist hanging from a shoulder strap.

His left hand grips the barrel of his rifle whilst the right is gripping the top of the firing mechanism. This looks like it’s a Carcano M1891. This was originally Italian made but did get exported to other countries in the Balkan region so this might have been acquired ‘legitimately’ or taken from the Italian invaders – the normal manner in which partisan (and guerrilla) armies arm themselves. On the butt there’s what looks like a carving of the double-headed eagle and a name curving around the top of that carving. It’s difficult to read the exact letters (I didn’t notice the carving when I was there earlier in 2015 but will check it on my next visit) but understand that carving designs, initials or names was a common practice at the time, showing both allegiance and possession. There’s a thick rope shoulder strap for ease of carrying.

His right leg is bent and his foot is resting on the ruins of a small mountain cannon. This is more than likely a Cannone da 70/15, which was produced at the beginning of the century but still in use in the Italian Army up to the time of WWII. (The 70 is the size in mm and the 15 the calibre.) On the arch there’s an image of a partisan pulling this gun apart with his bare hands. (A mountain gun of this sort was used two weeks after the Drashovice victory, in the mountains above Sauk, to attack the Quisling Assembly in Tirana.) Finally, he seems to be looking up to the 1943 Partisan, both literally and metaphorically.

The Second World War soldier is dressed as an officer in the liberation army. As normal he wears a cap with the star at the front and around his neck what would have been a red bandana, both indications that he was a Communist. A lanyard around his neck is attached to a pistol in its holster. Around his waist he’s wearing an ammunition belt, on the right side of which is attached a Mills bomb (British made grenade). The British were always trying to undermine the Communists in Albania, and continued to do so after the war, but according to a number of lapidars they did supply occasional munitions. His uniform is one that would have been able to deal with the cold of the Albanian mountain winter.

In his left hand he is holding what is almost certainly a Beretta Model 38 Sub-machine gun. This was produced in large number in Italy by 1943 and this would have been appropriated from the defeated Italian Army which had given up the war only a few days before the start of the Drashovice battle. This was a good choice of weapon as it was considered to be one of the finest of the comparable weapons produced at the time. (Here it might be worth mentioning that some of those Italians stayed in Albania and fought the Nazis with the Partisans and there are memorials to their contribution in Berat, Krujë and Çerënec.)

I have been told that this is not necessarily a statue of Hysni Kapo, the Partisan commander during the 1943 battle, but if the 1920 fighter is identified as a particular commander in the earlier battle against an invader then, I would assume, that this could, indeed, be Kapo.

Between the statue and the arch itself there’s what looks to me like an ‘eternal flame’ site. If that’s the case I don’t know if it was continually lit or only on special, ceremonial occasions. These aren’t common on Albanian lapidars but there are similar arrangement at the Monument to the Peze Conference and also at the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Elbasan.

As this is such a complex and detailed lapidar I intend to describe its complexity over the course of three posts. These will go under the name of ‘Arch of Drashovice 1920‘ and ‘Arch of Drashovice 1943‘.

Getting there:

I’ve found the best place to pick up a furgon that goes along the Shushicë Valley is by waiting beside the road in the square opposite the Vlora Baskia on Rruga Perlat Rexhepi (the Historical Museum is at the Vlora end of this road). Other furgons leave from this point but you want a furgon that comes the centre of town. Just flag down any one that comes from that direction (possibly going to Mavrovë or Kotë) and ask for Drashovice.

GPS:

40.44681902

19.58655104

DMS:

40° 26′ 48.5485” N

19° 35′ 11.5837” E

Altitude:

64.2m