Kukull to ward off the ‘evil eye’

The dordolec, the ‘evil eye’ and superstition in Albania

You think that when someone buys a soft toy or a blow up Tele Tubbie it’s destined for a baby or a young child. In Albania it could well be for another purpose. This is all part of the ‘tradition’ of the dordolec, the ‘evil eye’ and superstition in Albania.

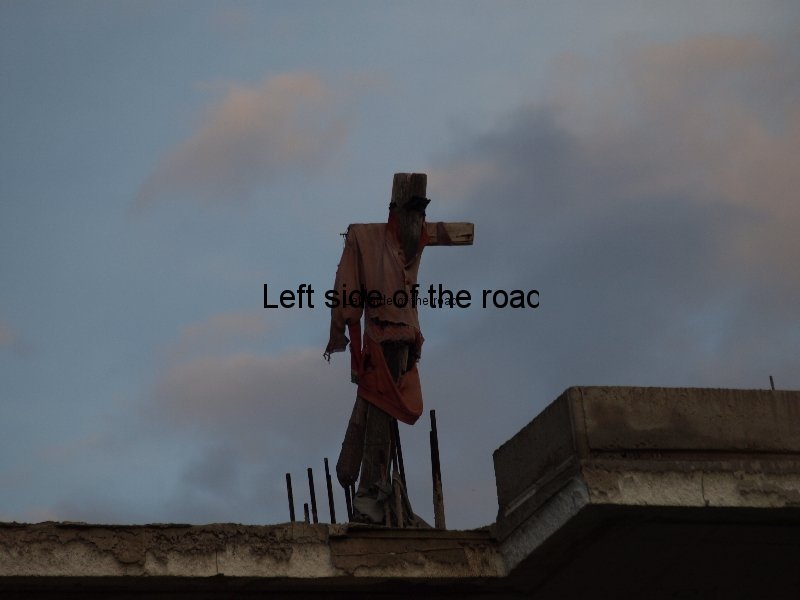

No one who travels around Albania, especially in the part of the country south of Tirana but to a lesser extent all over the country, can avoid noticing scarecrows in places you don’t normally see them, e.g., on the top floor of an unfinished building. Or soft toys hanging from balconies, fences, fruit trees and vines.

This is all related to the ancient superstition of the ‘evil eye’ and the attempt by the superstitious to retain what they have. And the instrument that is used to provide protection is the dordolec, whose meaning in Albanian covers scarecrow, doll, or guy (as in Guy Fawkes). Traditionally this would have been a figure, in the shape of a human, made out of old clothes stuffed with straw, and many of these can be seen in your travels.

Dordolec in Delvine

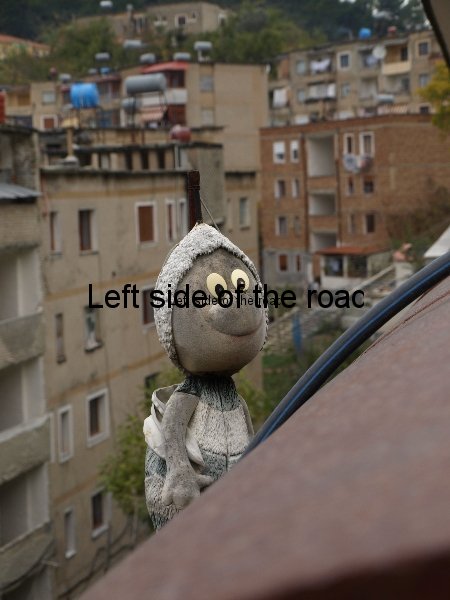

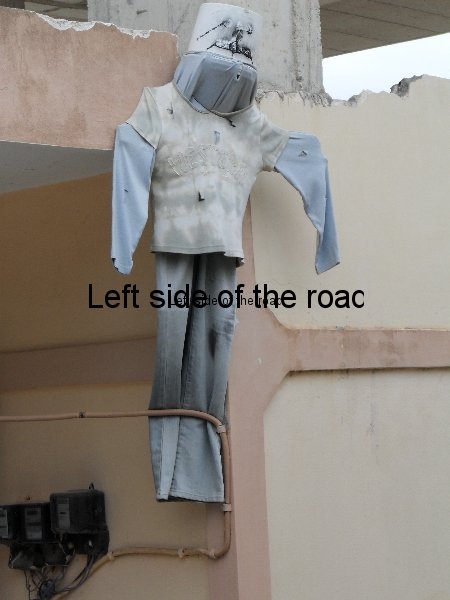

But there has been a reduction in what is necessary and anything that looks, sometimes only vaguely, like a human figure will suffice. This minimalist approach even goes down to just a shirt, arms outstretched and tied to a fence. However, new consumerism has been recruited into the 21st century version of this old superstition and you will often see soft toys (teddy bears, Smurfs, monkeys, etc.,) as well as blow up plastic toys of animals, Tele Tubbies or even Spiderman – one of the most surprising to me (on my first visit and before knowing what they symbolised) was a life-size version of Spiderman attached to the outside of an unfinished building. In Albanian kukull is the word for a store-bought soft toy and might be one of the words you hear if you ask the locals.

Kukull Smurf in Polican

It’s on buildings, either in the process of construction or perhaps not occupied as they are up for sale, that you are most likely to see the dordolec. But not exclusively. When travelling by road this is the impression you get but once you walk around Albanian towns and villages you begin to understand that they’re more ubiquitous. A small soft toy might be hanging from a grape-vine or from a fruit tree, a citrus or perhaps an olive, or just near the entrance to a family home.

The idea of the dordolec is not to frighten away people as the scarecrow ‘frightens’ birds, it’s more complex than that. The idea is the passer-by ‘fixates’ on the dordolec and in that way doesn’t covet the property on which it’s attached, it’s there to prevent envy which might lead to someone taking action to acquire that particular piece of wealth. It’s there to help reinforce one of the strictures of the Ten Commandments, the one about coveting your neighbour’s house, wife, servants or ox.

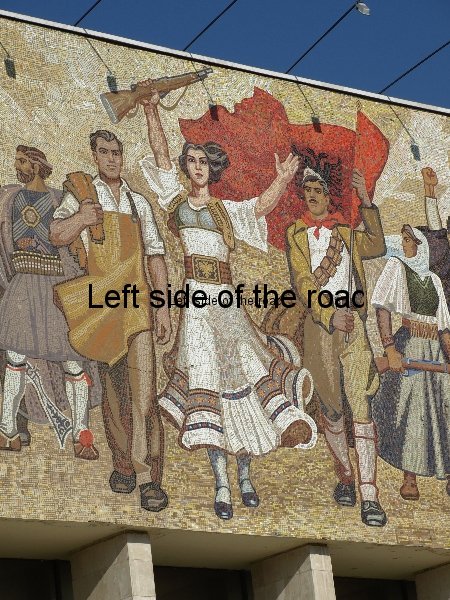

However, there is no direct correlation between this superstition and religious beliefs. In Albania such beliefs can be found in all religious communities, Muslim, Orthodox or Catholic – in fact I encountered less examples of the dordolec in the north, in the area around Skhodër, where the Catholic Church is particularly strong. And knowing the intolerance of the Catholics I’m sure that they would have come down on such superstitions with an iron fist in Albania’s feudal past and would be very wary if signs of it were to return with the end of socialism and the openly atheistic state authority.

There are a couple of theories as to why this tradition has again become prevalent. One is the stratification that has developed since the early 1990s between the rich and the poor means that people have a greater fear of losing what they have. This was not an issue under Socialism when land was the property of all the people but this all changed when land was privatised. And now that the population is caught up in the mire of consumerism they might have more to ‘lose’. This is a bit like the way homes in Britain are increasingly becoming like fortresses whilst at the beginning of the 20th century many houses didn’t even have locks, merely a latchkey. In the UK people install expensive locks and security systems, in Albania a soft toy suffices, so I suppose they are using a cheaper option.

Another theory is that this ‘tradition’ has been imported from Greece, where many Albanians have been forced to go to in order to find work after the wholesale destruction of industry in their own country in the last 20 years or so. Greece is not a country I personally know very well so can’t compare the situation between the two countries. This theory has some credence when you consider that the scarecrows and toys are more in evidence in the southern part of the country, especially around the town of Saranda.

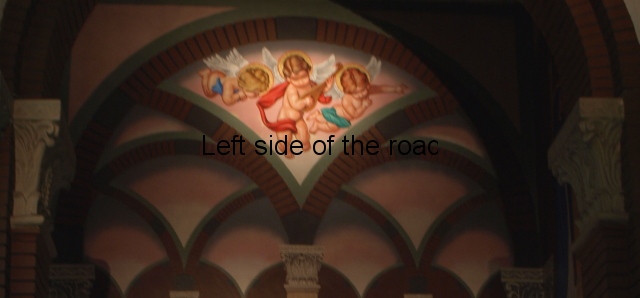

Ram’s Horns and Garlic, Saranda

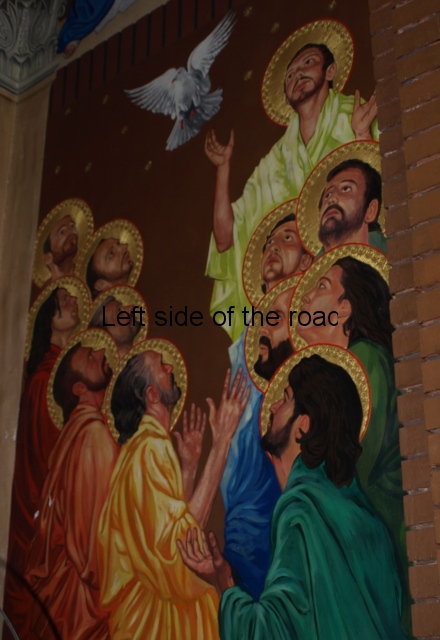

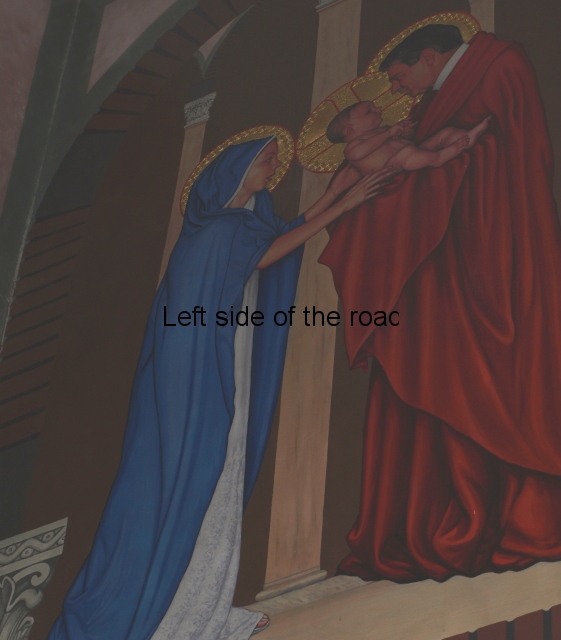

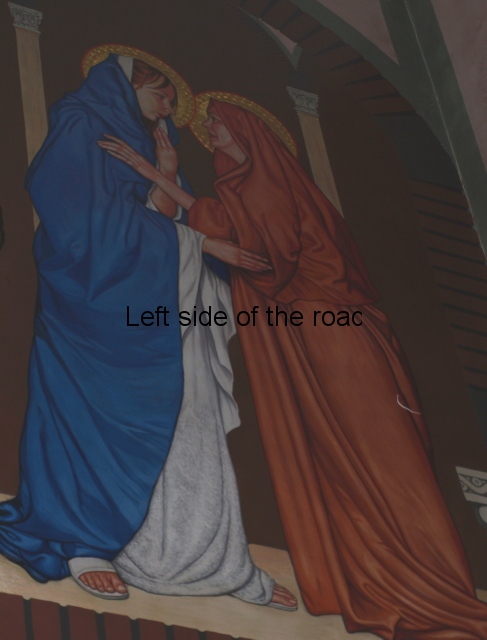

Whatever the exact reason for such an upsurge it seems to fit into a society that is looking for something to protect itself from the hostile world outside. In the same way that there has been an explosion in the construction of religious buildings (although I never experienced hoards of people going into those buildings in the way I would have expected if there was a true religious revival – I seemed to be entering more churches that the general population) perhaps the dordolec is a belt and braces approach to (divine or pagan) protection.

The positioning of such effigies on property goes along with other manifestations of superstition. Travelling around the country you’ll see a number of people, surprising to me especially older men, who walk around with worry beads in their hand. As well as that garlic, animal skulls/horns and horseshoes will adorn working businesses, especially shops or restaurants. Bunches of garlic sit on the dashboard of cars and other vehicles and once I even noticed a dordolec with a string hanging from it which had both a horseshoe and a rope of garlic, so they were definitely bringing out the big guns at that place.

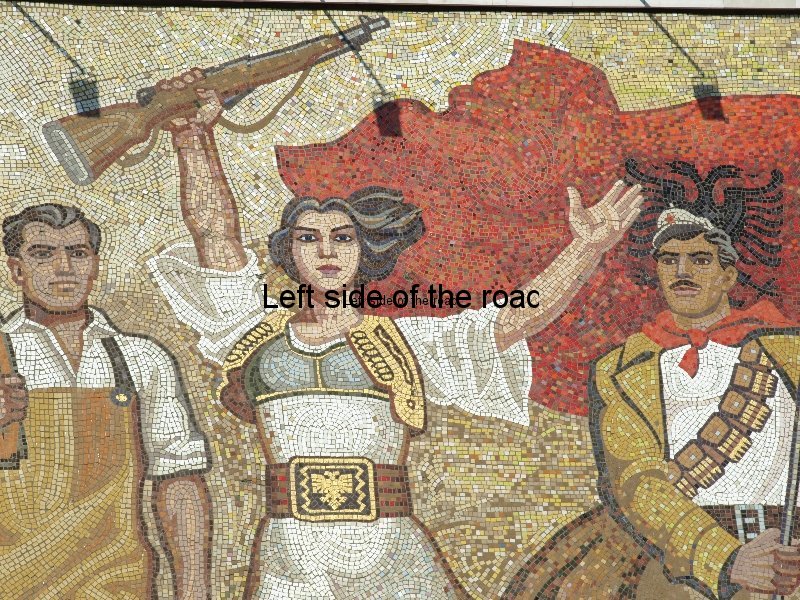

Religion in Albania

If you are interested in how beliefs in Albania currently manifest themselves you might like to click on these links for some other observations and comments: