Avtozavodskaya – Line 2 – Ludvig14

More on the USSR

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery

Moscow Metro – Avtozavodskaya – Line 2

Avtozavodskaya Metro station – now on Line 2 – was one of the seven stations completed during the anti-Hitlerite War and was opened on 1st January 1943. It’s original name was the Stalin Works Station, after the armaments factory that was above ground at that time. This name was changed in 1956 as part of the campaign against Socialism. Avtozavodskaya translates as ‘Car factory’.

Often the art work inside the Metro stations had a relationship with the area that the station served. In 1943 this area was one of heavy industry and some of the images reflect that fact. As time goes by areas change their use and importance in the economy of the country – especially in Russia as so much fell apart with the chaotic destruction of the Soviet Union. This creates a certain disconnect from the immediate area but the art can give pointers to the past.

It’s also common for there to be military references in those stations completed during the years of the Great Patriotic War as a way of increasing awareness of the need for the people to bear in mind the dangers the country was facing. There’s a permanence with the military references in the Soviet Metro stations but this would have been mirrored in the London Underground with its ‘public information’ (the British don’t use ‘propaganda’) posters.

All the Moscow Metro stations are bright but Avtozavodskaya is even more so as the columns are narrow and there are no walls between the central corridor and the two platforms. Together with the light bouncing off the tiles and marble that was used in the construction this means that when you come off the escalator you enter a large, bright and airy space, not really what you expect underground. According to the architect’s wife he got his inspiration from reading a book about plants whilst at the same time listening to Bach’s music.

On the Platform

On the platform level there are eight, long, narrow mosaics and four square stone bas reliefs – four and two on each side respectively. Between the bas reliefs there’s an empty space. This is the result of political vandalism that probably goes back to the latter part of the 1950s. If there’s nothing on show now then it almost certainly had a reference to Comrade Stalin, perhaps a mosaic with a meeting with workers, a Party celebration or perhaps, as the station was completed during the war, a reference to Stalin’s role in that war. Whether whatever was there was removed and destroyed or merely covered up I have no idea. There must be photographic records of the stations at the time of their opening but these remain elusive.

The Eight Mosaics

Armaments Factory

During wartime virtually all industrial production is given over to those products which support the war effort and for that reason half of the mosaics depict industrial scenes. Whereas the others show aspects of industry in general this one shows a tank production line – this could possibly be the famous T-34.

In the centre, and dominating the scene, are three, large completed tanks. In the foreground, to the side of the tanks are two groups of workers who are in the process of assembling the chassis of the next generation of tanks. In each group there are two men and one woman, all carrying out the same type of work. Three of the men are using hydraulic bolting tools. This indicates that women were working in industry in an equal capacity as the men, showing how the society had developed in just a generation.

Before the Revolution Russia was just a peasant economy with little industrialisation. That all changed with the rapid development of agriculture and industry in the 1930s. Without that development the Soviet union wouldn’t have been able to confront, and finally defeat the invading Nazis. At the time the mosaic was created the tanks would have been driven out of the factory and then immediately sent to the front.

Collective Farm

The growth of industry would not have been possible without the mechanisation and collective reorganisation of agriculture – in fact the development of one depended upon the development of the other. The next mosaic shows a scene from the countryside at harvest time at either a large collective or State farm.

In the centre we see the level of mechanisation with a tractor (with caterpillar tracks) pulling a combine harvester and a lorry alongside to collect the separated grain. Also to show how the role of women had changed since the Revolution a woman is operating the harvester. There’s another harvester slightly behind and to the left of the main subject – this one operated by a man, indicating the interchangeability of roles in the new society.

On the right hand side there’s a man and woman in conversation. She is holding, and reading from a sheet of paper. he is dressed in overalls and holds a wrench in his right hand. At their feet is a set of wheels. He is almost certainly a mechanic, a necessity in the countryside to keep the machinery in working order – especially at the busy time of harvest. She could well be a Brigade leader going through the progress of the jobs he has been allotted or telling him what he should do next.

Here it’s important to stress that it was only in the Soviet Union, at this time, where women were in positions of responsibility and authority. I’m not saying that complete equality existed in the Soviet Union in the 1940s but at least there was an effort to create such a situation. It took the capitalist west more than a generation to get even close.

On the left hand side is a small group of three, two men and a woman. One of the men is much older, with a white beard and wearing glasses. He is not dressed for working in the fields as he is dressed in a white suit. He’s inspecting the ears of the corn which is in the sheaf that the woman is holding. He would be a scientist checking the quality of the harvest. The third member of the group is a younger man, taller than the older man, dressed in farm clothes and sporting a black mustache. He’s looking on the inspection process awaiting for the verdict.

The whole scene is a reference to the way in which Soviet agriculture had to advance. It was bringing mechanisation and industry to the countryside together with advances in science to ensure a bountiful and healthy crop. This is the basis for modern agriculture and was a million miles away from the feudal level of agriculture before the Revolution.

Commercial Port

The next scene is of a busy commercial quayside – almost certainly not Moscow – which is a hive of activity.

The centre of the panel is the background, across the dock from the quay on which the people are standing. Here we see a large crane in the process of loading (or unloading) a cargo ship, whose mast is right of centre. Behind is the outline of quayside warehouses and on the right there’s steam billowing out from an electricity station cooling tower.

On the right hand side the background is created by the black stern of a large ship that’s tied up to the dock. There are what looks like two chains coming down from the (unseen) deck of the ship to two bollards on the dockside. This is strange as you would never tie up a ship, of whatever size, with chains. I can only surmise that the artist knew nothing about the actuality of a port and guessed at what would have been used. There’s no problem with artists (and intellectuals) not knowing the facts, it’s another that no one sought to enlighten him/her.

Standing on the quay in front of this ship are two people, a man and a woman, involved in fishing. He is still dressed in his oil skins and is holding up a large fish in both his hands. He’s smoking a pipe. The woman is bent over emptying a large basket of fish on to the quay at the same time as looking at the fish the man is holding as if to say ‘It’s been a good catch’. At the extreme right hand edge a number of barrels are stacked and I would think this is for the salted fish that would have been the main way that fish was preserved in the 1940s. Laying parallel to the bottom of the panel is a large fish – this will almost certainly be a sturgeon, long time associated with Russia (for its caviar).

On the left hand side a group of three men are in the process of loading barrels on to a lorry. The man at the rear of the vehicle is guiding a barrel, which is hanging from the hook on a cable from an unseen crane, on to the flat back of the truck. To his left the other two men are in the process of connecting another barrel to the hoist line.

The man on the left is older, is dressed in a white suit (a bit inappropriate for dock work I would have thought) , is wearing a cap and holds the hook end of the loose line in his hands. The other man, to his right, is standing behind a barrel ready to help him connect the line. All the three men are wearing large, white protective gloves.

Behind the lorry, and on the edge of the quay, are what could be bales of rope. On the extreme left hand side of the panel is a small stack of sacks, waiting to be loaded on to the next truck, perhaps.

Behind this scene a small, two-masted sailing boat is in the process of coming into the picture.

Foundry

There are flames everywhere in this scene from a foundry. On the right hand side we see two men guiding a large crucible of molten metal, hanging from an unseen gantry crane. which they’ve just taken from the furnace, the metal giving off a glow at the top. They are taking this over to the left hand side where two other men are in the process of pouring metal into a cast. With large casts the process has to be continuous and organisation is the key. At the cast you can see the white stream of metal leaving the crucible and the whole process is being supervised by a woman who is on the other side of the cast to the men. She is wearing protective googles and a hat but otherwise seems to be wearing ordinary clothes.

The only other person in the scene is a woman who is standing in the middle, between the activity of casting. In her hand she is holding a small piece of testing equipment. It’s close to her eye as if she is looking through a small glass window to inspect whatever is inside. There’s a small hopper at the top of this device which would allow the insertion of what she wants to test. In a foundry everything depends upon the quality of the sand and the moulds into which the metal is poured and I assume that it’s somewhere along the line of this testing process that is her responsibility. She has a clip board tucked under her left arm and she is wearing ordinary working clothes.

There’s a nice little touch at this point in the mosaic. As I’ve said there are flames all around and what the artist has done is to give her a shadow so to her right is a larger silhouette of herself.

Assembly Shop

The next mosaic is another industrial scene – this time in an assembly shop. On the right a woman is riding on an early electric fork lift bringing in a container of links for the production of caterpillar tracks. This appears to be an assembly shop for small tracked vehicles, putting these tracks together seems to be what is happening on the left hand side. The size of the tracks are far too small for military use so it’s likely that this part of the factory is making agricultural equipment – as important in the war effort as armaments.

It’s difficult to work out what’s the two men in the centre are doing but it’s obviously another process in the production line. This is only one small part of a very much larger factory as can be seen from the large presses in the background.

Forge and Pressing Shop

We are in another part of the factory for the next mosaic – this looks like the pressing shop. On the right hand side a man is taking a long, heavy piece of metal from the furnace, looking over to his left to see if they are ready for the next piece to process. He grabs the white-hot metal with a long pair of tongs, the weight of the metal being born by a rod that hangs down from a pulley system.

In the centre two men are in the process of the initial shaping of another piece of metal, standing in front of a hammer press which gives the metal close to its final shape. The metal still being hot from the furnace the sparks are flying in all directions. One of the men, on the right, is wearing goggles whilst the other, his right hand holding the long tongs, uses his left hand to hold a welders mask in front of his face. The man on the right seems to be holding a hose which is directed to where all the sparks are flying. Is this a jet of air? i don’t know enough about these processes to be able to say.

The other worker, on the far left, is working alone at another, perhaps smaller press. The metal is still white but it’s shape is now more defined, getting closer to its required format. Standing slightly facing the viewer we can see that he wears full protective gear and goggles.

So here the artist has sought to present three stages of the pressing process. Perhaps these are meant to be the presses seen in the background of the assembly shop.

The Red Air Force

Most of a Soviet twin engine medium bomber dominates the mosaic that refers to the Red Air Force. We know it’s a Soviet plane by the large red star on the tail fin. It’s possibly an Ilushin Il – 4 or a Tupolev Tu – 2.

Standing behind the wings are two airmen (of a three man crew), one with a map in his hands as if they are discussing the upcoming mission. They are possibly the pilot and navigator.

The bomb bays are open and two of the ground crew are loading large bombs by way of a hoist into the aircraft. Standing at the front of the plane, looking up into the air with a pair of binoculars, is possible the third member of the crew – the gunner.

In the background is another bomber sitting on the apron and looking underneath the belly of the aircraft can be seen a truck.

The Red Navy

The last of the mosaics commemorates the Red Navy and is a very busy picture. In the background, and taking up the full length of the mosaic is a large battleship in full steam – with smoke coming out of its twin funnels and creating significant waves. There’s a red flag flying from the bow with a large golden star.

Dwarfed by the battleship a small, two man speedboat is racing alongside, its bow up out of the water. There’s a red flag from both the bow and the stern.

On the right of the scene two men appear to be on the top of a coning tower of a submarine. One is already in place and is sending a semaphore message. His comrade is climbing up the steps to join him.

On the left hand side, in the foreground, are three sailors at a bow gun on yet another ship. One of them has a shell cradled in his arms and is about to push it into the open breach. The second sailor is looking ahead as if to work out the settings to make on the gun. Another sailor stands behind the gun but we only see parts of his uniform.

A couple of things stand out in these mosaics. One is that the skill of the artist is such that all the faces are distinctive and unique. You get an idea of what they are thinking as they carry out their tasks. Another is that women were always represented in an equal manner apart from those images which show the armed forces. Women did take an active and front line role in the Great Patriotic War (I’m not too sure about the Navy) but very often in women only squads.

Four Bas Reliefs

The bas reliefs are divided equally into rural and industrial scenes but one thing that unites them is the way they have been constructed. They are very large (I can’t say exactly as they are high up and on the other side of a railway track) but instead of being carved on to one piece of stone they are very much like a jigsaw puzzle – but a puzzle that has different sizes of blocks each time.

Aircraft Production

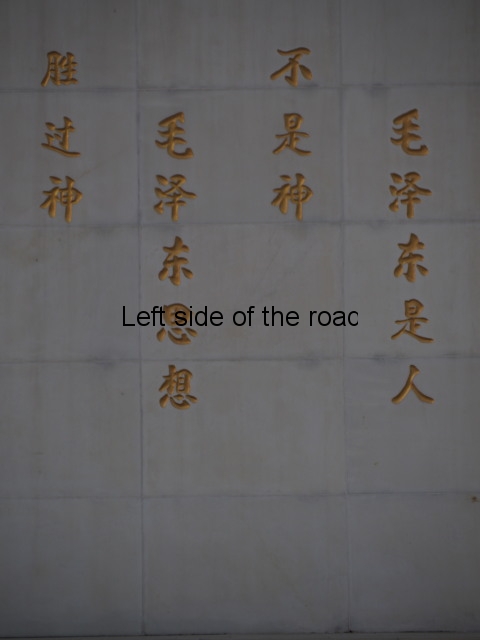

Socialist Realist Art is not always realistic. It’s a way of telling a story about the life of the workers and how they are attempting to build a new society. It’s an art form which places workers and peasants at the centre of public images which does not exist anywhere outside of those societies that have made a revolutionary change to the previous exploitative and oppressive society. And we have an example here which introduces unreality into a Socialist Realist image.

The male kneeling is in the process of servicing an aircraft piston engine, the engineer standing on the right hand side is making notes on a clip board. The hook at the top is ready to take the engine for repair. But in 1943 how many Muscovites would have known where the engine came from? How could they relate to an important part of the defence of their city and country?

That’s easy. Add a couple of men dressed in pilots uniforms and give one of them a propeller which is taller than himself. It’s not very sophisticated but it’s no more strange than Catholic martyrs being depicted with the instruments used in their death. And there’s nothing strange in works of art being produced in a Socialist society which bears the hallmarks of the old society, including its religious imagery. I discussed this in the post about the statue by Odhise Paskali (Shoket- Comrades) in Permet Martyrs’ Cemetery.

Until a new form of art, which has been able to develop outside of the influences of capitalism, then Socialist art will always exhibit aspects, tropes, of that old society. It may look strange but that is all part of the development of ideas and how those ideas can be communicated in a way that ordinary people can understand and appreciate. We must remember that the Constructivists, at the beginning of the 1930s, moved into design and away from painting because ‘paintings could not be understood by the masses’.

Harvest Time

This is another harvest scene – but it’s difficult to work out which part of the vast Soviet Union the scene is set. I thought perhaps in the Ukraine – as the bread basket of the country – and then Georgia – due to the connection with Joseph Stalin. But couldn’t come to a definite conclusion. The head-dress of the young woman on the right is quite distinctive as are the boots of the woman on the left.

This is the harvest as the woman on the left is dragging a sheaf of grain in both her hands and the woman on the right is plucking fruit from a tree and has a basket of fruit balanced on her right shoulder. One of the children is ‘helping’ the other looks bemused – as does the young foal in the centre of the image.

Life in the Tundra

This is another rural scene but this time from the tundra. But I’m not sure how to interpret what we see. On the far right we have a young woman who’s holding a somewhat struggling goose. Sh’e got a grip of the goose’s left wing under her arm but the goose’s right wing is flapping and fluttering above and in front of her face. She’s also dressed in light summer clothing, as is the little girl at her feet.

The man appears to be putting on a heavy winter animal skin coat and is half dressed for different seasons. When we go further to the left both the woman and the small child (are they the same as on the right but at a different time of year?) are dressed for the harshest of winters, complete with a reindeer.

Precision Engineering

Finally, we have another industrial scene – a little bit more straightforward than the first bas relief, but only a little bit. Here we seem to have different aspects of production brought together but with little clue as to how they fit together.

Of the two central characters the one standing is dressed in a suit and is using a set of dividers on a sheet of paper that’s resting on the knee of the man sitting. This could be a designer explaining to one of the workers what the nature of the task he is asking him to carry out.

On the right hand side we have a standing worker who is dressed in the same sort of protective gear we saw in the mosaic about the foundry – together with the large tongs to be able to manoeuvre the white-hot metal.

On the left hand side there’s a female worker cradling a cannon shell in her arms so that indicates that the action is taking place in an armaments factory.

There is a tenuous connection between the mosaics and the bas reliefs but I don’t think that in Avtozavodskaya the connections had been fully thought through. There is much more of a unified theme in many of the other stations.

The more I look at these bas relief the less I like them – a shame when there are so many wonderful examples on the Metro network in general.

At the top of the escalators

The Defence of Moscow

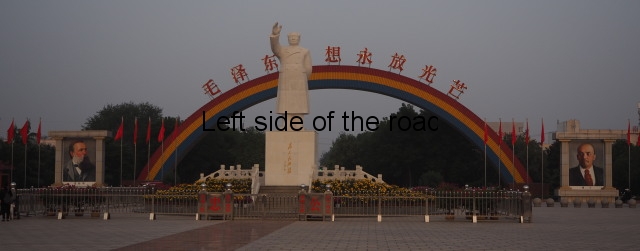

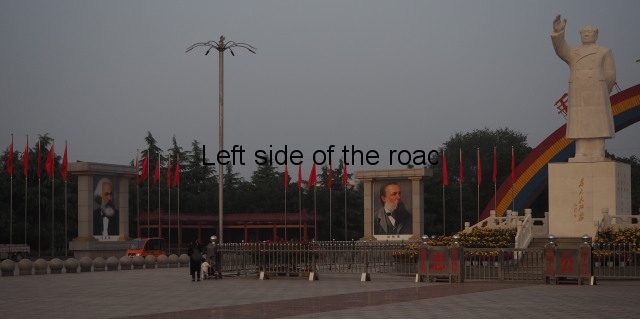

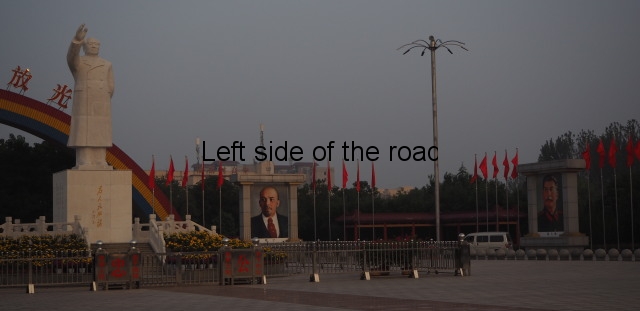

The large mosaic at the top of the escalators is very different, in many ways, from those that run alongside the platforms below. The materials that make up the mosaic are different; here they are much larger pieces of cut stone, which covers a range from brown through to green and on to yellow. The feel is also different in that this is one of celebration, the celebration of the end of the blockade of Moscow (that lasted from October 1941 to January 1942) and the beginning of the counter-attack which would eventually lead to the destruction of the Hitlerite forces in their own lair in Berlin in May 1945.

I have no idea of the artist of this mosaic – it’s certainly not Frolov, he would have been trapped in Leningrad when the decision was made to create this celebratory work of art and it’s so very different in style from his other designs in the station.

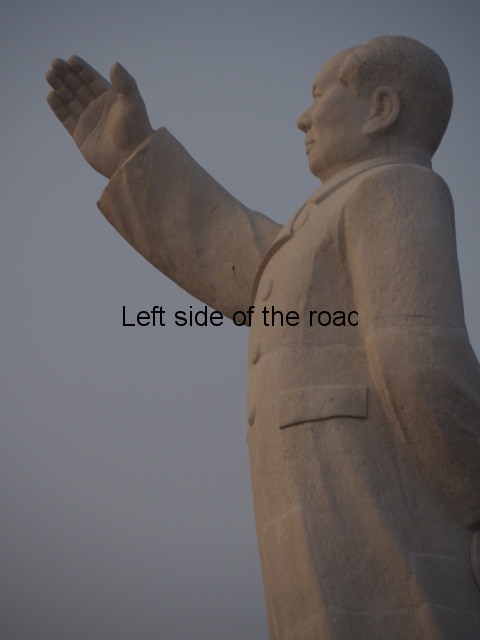

The design is on two planes. In the foreground we have the Russian Red Army. In the centre, coming straight at the viewer, with its gun barrel pointing at you, is an almost life-size depiction of a tank.This is quite probably one of the many versions of a T-34 tank – the most produced and most successful tank of the Second World War (although the drivers gun should be on the right hand side at the front). However, this tank is not in fighting action, more as part of a celebratory parade as the central figure of three who is standing on top of the tank is saluting.

Presumably he’s the tank commander and on his right, slightly behind, is another tank crew member, wearing the classic Russian ribbed tank helmet. In his hands he holds a gun of some kind (a little indistinct) and he is looking over to his right. Below him, and on the cowling over the right hand caterpillar track, is another soldier behind a heavy, wheeled, machine gun. This is probably a PM M1910 Maxim Machine Gun. (This weapon seems to have had an even greater longevity that the AK47 Assault Rifle – having been produced first in 1910 and versions reported to have been seen in the Ukraine in 2017.)

To the left of the commander is another soldier, facing forward and probably not from the crew, who has the butt of his long rifle – with bayonet attached – resting on the cowling over the tracks of the tank. He’s wearing a greatcoat and has the straps of a dispatch pouch, which rests on his left hip, across his chest. It’s possible to make out a star on the front of his fur hat. To his left is another soldier, kneeling with one knee on the cowling of the tracks, and in his hand he holds a tommy gun – the circular ammunition magazine clearly seen. He also has a star on his hat.

On either side of the principal tank are two other tanks with their gun barrels fanning out. Here we move away from the idea of a celebratory parade and get the impression that these weapons are ready to cover all areas in defence of their city and State capital. There are no people seen on these defensive tanks.

And what they are defending is the city of Moscow. Whereas the tanks and soldiers were in yellow and brownish stone the city itself, in the background, is constructed of gradations of green stone. We know it’s Moscow as three of the iconic towers of the Kremlin are shown with their distinctive red stars. Those stars, lit up at night, still shine to this day. During Soviet times the ‘Hammer and Sickle’ was attached to the stars but unfortunately they have been removed now. The other towers in the image have flags flying from their summits.

Kremlin Star with Hammer and Sickle

In the centre of this representation of Moscow is a strange figure. Merging into the buildings is the upper torso of what looks like a warrior from the 16th century as we have a mustachioed and heavily bearded face and he wears a Turban helmet on his head. Although no hand is visible a large spear is on his left side, the point extending as high as the stars on the Kremlin towers. To make matters even more strange this figure is saluting, mirroring the action of the (smaller) tank commander below.

I can only guess who this is supposed to be. My suggestion is that this is a representation of Tsar Ivan IV ‘The Terrible’. He fits into the time scale and he had a relationship with Moscow (as ‘Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533-1547, before he became Tsar and it was in this period that the St Basil’s Cathedral – the multi coloured, domed building at the end of Red Square – was built). But why he should make an appearance in a celebration of a victory by revolutionary workers and peasants I don’t know.

Ceiling mural

If many of the thousands of travellers who pass through this station don’t notice ‘The Defence of Moscow’ mosaic before jumping on to the escalator down to the platform even fewer will be aware of the large ceiling mural that covers most of the area above the vestibule.

It is a circular design with a sun effect, offset from the centre, which has lines radiating out in all directions. Cupping underneath the sun is the arc of a huge sickle which is made up by different red coloured, parallel sheaves of grain, the staggered heads creating the serrated effect found in most representations of the peasantry in the Soviet emblem. The handle of the sickle is made up of a combination of a maize cob, some more sheaves of corn (flowering) and a sunflower head.

Passing underneath the sickle, close to the handle, and also in red is a large hammer – the representation of the proletariat. This is a geometric presentation of industry with symbols for electricity (the zigzag design and a couple of insulators), coal mining (a couple of underground trucks), girders, cogs and diagrammatic representations of different machinery.

Just above the ‘sun’ and close to the edge of the main design is a large red, five-pointed star – the symbol of Communism. If we go clockwise from that star we come across different aspects of Soviet society, related to work, leisure and science, all in a simple, basic (even primitive) style.

First there’s an oval sports stadium. from inside this structure a very tall flag pole emerges and it flies a flag with the letters ‘CCCP’ (USSR). Below the stadium is another symbol I haven’t yet been able to work out.

Continuing around next are a couple of male football players, tackling each other for the ball just in front of a goal mouth, part of the net is shown in blue. Below the lower player there are three flowers in front of what might be the outline of a building.

The other side of the handle of the sickle is a large building which might be a school or a Palace of Culture – it’s certainly not anything to do with industry. The building has a large main entrance with steps coming up from street level. There are clouds in the blue sky and to the left of the building there’s a tall tree, and below that are a couple of smaller shrubs. Scattered around the grass in front of the building are numerous flowers. In the bottom corner of this sector is a mask, a common symbol used to denote theatre in general so whether this is suggesting that the building is a theatre or reinforcing the idea of the arts I’m not sure.

The next segments introduce the world of work and industry, more specifically the production of automobiles – which gives the present name to the station. I can’t work out exactly what is happening in the first bit but it seems to me all part of the production line process. The first man seems to be moving things on the line and in the second segment two men are moving a completed internal combustion engine on to a chassis. Next we have a man and a woman beside a milling machine. He seems to be holding a piece of paper in his hand, perhaps the design specifications for the piece of work she is about to create. She is on the point of putting on safety goggles indicating that she is the skilled person to be doing the work – again an example of how advanced the Soviet Union was (even in its Revisionist stage) in moving towards equality between the workers – not perfect but at least heading in the right direction.

That’s the scene inside the factory the next image is of the exterior of the factory, with its smoking chimneys, the smoke being blown in the wind.

The story then moves on to scientific advances. A male is sitting at a what looks like an early computer control console. In his left hand he holds a board, perhaps with data he’s inputting or a series of instructions. This might be a reference to the nuclear industry as the next symbol is one of those for nuclear energy, with three protons circling around a neutron. On the edge of the circle is a meter so this could well be a Geiger-counter.

Finally, as we come almost full circle, we come to the exploration of space. Following the curve of the circle we have the trail of the launch of a rocket (in red). This trail bisects the atmosphere between that of space and the Earth’s. In the darkness of space we see a satellite and crossing between the two we see a capsule returning to Earth, with its parachute deployed to slow it down in the heavier atmosphere. In the background are the stars.

There’s little text in this image but what is there declares the aims of Socialism; CBOБOДA (Liberty), PABEHCTBO (Equality), БPATCTBO (Fraternity) and CУACTЪЮ (Happiness). Also on some of the red lines that swirl around the space around the design can be seen the word MЍP (Peace).

It’s difficult to date exactly this design. It looks to have been heavily influenced by the designs of the likes of Andrey Gulobev and Daria Preobrazhenskaya, who both worked in textiles, in the early 1930s. Looking at the state of the technology I would guess at the late 1970s. The Moscow Summer Olympics took place in 1980 and with the messages in the text it would make sense that this, relatively new addition to the decoration of the station, was created in readiness for this event with many foreign visitors using the Metro.

Avtozavodskaya station plaque

In many of the older and impressive stations there will be a plaque giving information about when the station was opened and who was involved in the construction. These plaques are normally found at the bottom of the escalators to the platforms.

In Avtozavodskaya we know it opened on January 1st 1943 and that it had a name change – as stated at the beginning. Also the architects were Alexey Dushkin and N Knyazev. Dushkin (24th December 1904 – 8th October 1977) also worked on Kropotkinskaya (1935), Ploshchad Revolyutsii (1938), Mayakovskaya (1938) and Novoslobodskaya (1952) as well as the Red Gates Administrative Building (1953) – one of what are known as ‘The Seven Sisters’, the huge buildings which sour into the sky in the centre of Moscow which were built after the war. I’ve not been able to find out anything about Knyazev.

The mosaics were created by a V Frolov. I think this must be Vladimir Alexandrovich Frolov (1874, St. Petersburg – 1942, Leningrad) as he is the only Frolov mosaic artist I have identified. If this is the case then he would have died (of starvation in the 872 day Siege of Leningrad during the Great Patriotic War) before the work was completed. This would be possible as plans for the construction and the decoration would have been made long before the actual opening of the station. Whether he ever saw any of his designs in actuality is unlikely but it’s almost certain he never saw the completed art work.

When I first started to investigate the history of the Moscow Metro I thought that all of the early stations were built well underground. That’s not the case. Why I don’t know – as yet. Especially as this station would have served the workers of an important armaments factory.

More information on the station;

Avtozavodskaya

Date of opening;

1st January 1943, known as Zavod imeni J.V. Stalina till 1956

Construction of the station;

deep, column, three-span

Architect of the underground part;

A. Dushkin

The architect of Avtozavodskaya A. Dushkin wrote: ‘I like this station because it is made with one breath. It clearly manifests the constructive essence and, a s with Russian temples, the clearness of the working shape’. However, as his wife revived, the design of station ‘Zavod imeni Stalina’ required considerable creative efforts from Alexey Nikolayevich: ‘I remember well how the project of station ‘ZIS’ (now Avtozavodskaya) was developed. My husband made some drafts, which did not satisfy him, he put off the work and was deep in the book of Timiryazev ‘Life of Plants’. He ignored my questions why he needed that and only asked to play Bach’s fugue. When finished the book, he sat down at the drawing-board. He made eleven drafts of the station but chose only one, which was realized. For me the character of the station is music and polyphony. While going down by the escalator, the columns appear one by one and then as if combine in common sounding – as the finale of the cadence brought to key…’.

The design and architecture of Avtozavodskaya is a variation of Kropotkinskaya. The high thin columns support the flat vaults. Starting from the caps, the columns broaden upward and form ribs, which flatten, as if dissolve in the vault, without closing in. The columns are faced with marble of the Altai Oroktoyskoye Deposit – light with black and lilac veins. The walls are faced with marble of the Prokhoro-Balandinskoye Deposit – light, mostly cream-coloured, baked-milk-coloured, ivory-coloured. The floor is covered with black diabase with the geometrical ornamental pattern made of square inserts of red and grey granite.

There are smalt mosaics ‘Soviet people within Great Patriotic War’ (designed by F. Lent and V. Borodichenko, craftsman V. Frolov), forming broad friezes, above the facing of the walls – four on each side. The mosaics of the eastern wall are devoted to workers of ZIS (now ZIL). The western wall glorifies battle and peaceful work of the peoples of the USSR, which is possible due to implements manufactured in the ZIS plant.

The pair bas-reliefs made of greyish-yellowish Moscow limestone are on the walls in the central part of the station – ‘Pilots and constructors’/’Metallurgists and engineers’ (eastern wall) and ‘Peoples of the North’/’Peoples of the Caucasus’.

Southern ground vestibule

The two-storied southern pavilion is coeval with the station. The front is adorned with the semi-columns of Labrador and very high decorative glassed arches of doorways with figured cast bars. The rectangular entrance hall of the station is behind the doors. It is connected with the round hip escalator hall by the wide bow-shaped passageway. Four doors to service rooms are decorated with marvellous cast-iron bars with florid ornament in the Russian ‘grass’ style. The walls of the vestibule are faced with whitish marble of the Uzbek Gazgan Deposit, while the walls of the passageway and entrance hall are with snow-coloured and cloud-coloured marble of the Ural Koelga Deposit. There is a big mosaic panel of many-coloured marble on the wall opposite the escalators – Parade on the Red Square. A partisan with a Maxim machine-gun, pilot, tank commander, soldier with a Mosin rifle, fighter with a Shpagin submachine-gun are on the armour of the tank, forming a pyramid. The central figure of the composition is the saluting tank commander. An epic hero with ancient Russian helmet as a mount rises behind the defenders of the Motherland. He covers his eyes with his hand looking at onlookers who seem that he also salutes. The Kremlin on the background is reliably protected.

The vault of the entrance hall is decorated with painting on plaster – ribbons, orders, sparks of salute, sketches of work and rest of ZIL workers. There are also words: Peace, Labour, Freedom, Equality and Brotherhood.

Text from Moscow Metro 1935-2005, p82/3

Location:

Danilovsky District, Southern Administrative Okrug

GPS:

55.7074°N

37.6576°E

Depth:

11 metres (36ft)

Opened:

1 January 1943

More on the USSR

Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery