Mushqete Monument – Berzhite

In the last days of the fight for the National Liberation of Albania by the Communist led Partisan army a crucial battle took place along the road from Elbasan to Tirana, south-east of the capital. To commemorate this battle the Mushqete Monument was erected at Berzhite.

The battle for Tirana had begun at the end of October (after much of the southern part of the country had already been regained by the liberation forces) and the Hitlerite forces decided to make a last desperate attempt to put off the inevitable by sending a column of about 3000 soldiers, with tanks, artillery and other armoured vehicles, from Elbasan. In the original plan they also wanted to send a similar force from Durres, on the coast, to create a pincer movement but that second force never materialised.

Four brigades of the National Liberation Army, consisting of about 1,200 men and women partisans, ambushed this column along the road (now the SH3) between the villages of Mushqete and Petrele on the 14th November 1944. The battle continued into the following day but by 18.00 of the 15th the battle was over. The German forces had suffered 1,500 dead and wounded and the remaining forces were captured. There is no information on the number of Albanians killed or wounded.

This was a no holds barred battle and contemporary reports talk about the route between the villages of Mushqete and Petrele being littered with corpses, of both men and horses, with the road and grass verges painted red with blood.

Victory in this battle, just 10 km from the capital, ensured that by 17th November Tirana was under the complete control of the liberation forces and within another two weeks the war was all but over for the German forces when they suffered another defeat in the northern city of Skhoder on the 29th November. That day is now celebrated as the date of the liberation of the country and the beginning of true independence.

On the occasion of the 25th Anniversary of the battle of Mushqete a monument to this important encounter was inaugurated in 1969.

The sculptor was Hektor Dule who worked with the assistance of the architect K Miho. Dule will appear on this blog again as he was the sculptor of a number of important works of the socialist period in Albania’s history but, unfortunately (so far) I have been unable to find out anything more about Miho.

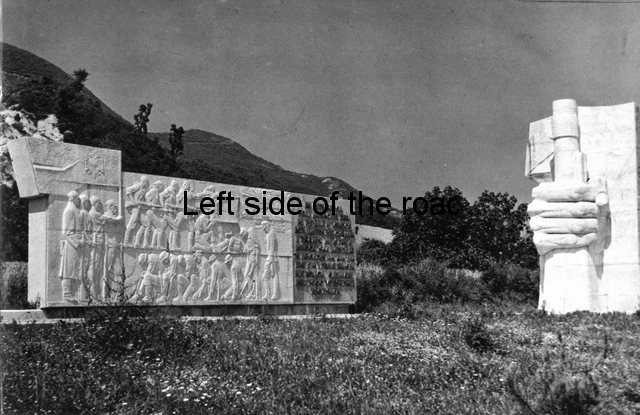

It’s quite a unique piece of work in the Albanian context as the monument is in two, very distinctive, parts.

The first part is a large, rectangular panel depicting the symbolism of the Communist Partisan forces as well as the specifics of the conflict. This would have been made from a mould into which the concrete was poured and then set upright in its present location.

Many of the Socialist Realist monuments in Albania were made of concrete (beton in Albanian). This was a readily available and relatively cheap material (which accounts for its popularity) but I can’t think of any monuments in the UK which use the same basic material. At the same time lifting such a large panel must have been a complex and difficult task, fraught with difficulties. Concrete can be robust and durable but it does have its weaknesses and this particular piece would have been vulnerable as it was being manoeuvred from the horizontal to the vertical.

The panel is, roughly, 3 by 10 metres (not counting the panel with the text). When I visited in November 2014 it looked as if it had been recently whitewashed. As far as I can tell the original was just the bare concrete and there was no paint at all involved, i.e., no highlighting of the red stars as was the case, for example, on the Dema Memorial close to Saranda.

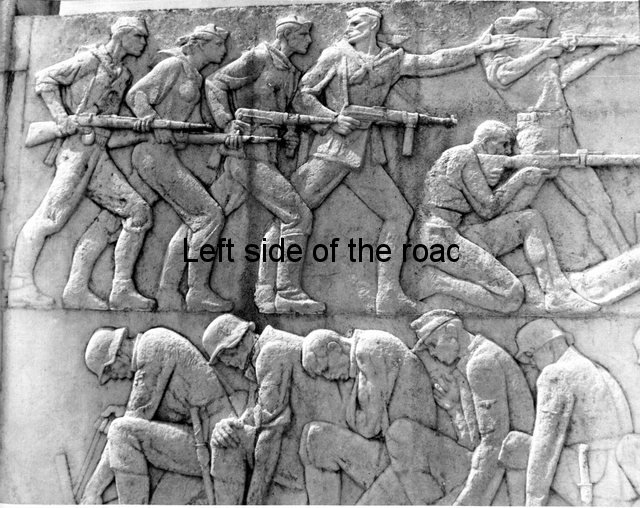

There are two distinct stories being told in this one image, one of victory and the future, the other of ignominious defeat. These two narratives are separated on the horizontal plane.

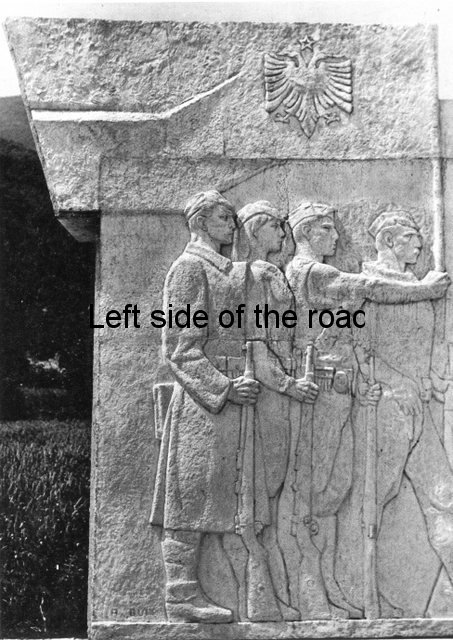

Starting from the left we have a group of four Partisans (three men and one woman), about life-size, all with the barrel of a rifle in one hand. The man at the front also holds a flag pole and the national flag then goes back over their heads, extending behind the group. The way it has been designed giving the impression it is fluttering in the wind. On the flag is the double-headed (black) eagle with the star (which on the cloth flag would have been in gold) sitting just above and between the two heads of the mythical raptor.

From here the panel is divided into two. On the top section, the one representing victory, there are six Partisan fighters, 4 men and two women. The first four (three men and one woman) are marching to the front, all armed, the first man looking back and urging them on. They are going towards two fighters (one of each gender) who are already firing at the enemy, the woman standing and firing a rifle, the man kneeling with a light machine gun. The machine gun is resting on a box with the letters WH but I’m not sure what they stand for. Lying on the ground under the machine gun is a male in civilian dress and this has been suggested to me to represent the Quislings (those collaborators and traitors which infected most of the countries invaded by the Fascists). This one will no longer be a problem as he has suffered the same fate as had been meted upon the 1,500 Hitlerites at the end of the 15th .

They are all heading, or shooting, towards the German Tiger tank which has been disabled and is on fire. This represents the armoured German column that had started out from Elbasan.

There are a few points to stress about this depiction of the Albanian Communists. They are all moving forward not only in battle but also in the sense of the Socialist future of their country. They show determination and a sense of dignity and purpose. They are marching and looking towards their capital of Tirana with their heads held high. On their caps they proudly display the star of the Communist Party. And, as I’ve mentioned before, not least in the post about the Albania Mosaic on the National History Museum, the women depicted are fighters, armed and prepared to use their arms, in the fight for their own liberation – these are no shrinking violets who wait at home for the men to ‘give’ them freedom.

The representation of the Nazi invaders couldn’t be any different. They occupy the lower part of the panel.

Starting from the right there’s a German officer, head bowed, standing in front of the useless, burning tank with his head between the tracks. In front of him is a standard-bearer, bent even lower and in his left hand he holds the regimental banner, with the swastika which is now being dragged in the dirt. Just the opposite of the Albanian flag which flies so proudly at the far left of the panel. This is also reminiscent of the Nazi standards being thrown down on the cobbles of Red Square in Moscow, in front of the Lenin Mausoleum with Stalin on the podium in May 1945.

Next we have a group of six men, all on their knees and now underneath the marching and fighting Partisans. They are all looking in the direction they had come, i.e., away from Tirana which was their goal when they left Elbasan. Five of them wear either a military helmet or cap but the one-fourth from the right is bare-headed. I can’t see anything defining him as a soldier so this might possibly be another representation of a collaborator.

Some of the faces of the defeated fascists look quite skeletal. In November 2014 I thought this was the deliberate intention of Dule but after seeing the black and white picture (taken no later than 1973) I believe this is just a consequence of time, whether deliberate damage or the ravages of the weather it’s impossible to say.

The extreme right hand side of this large panel is taken up with text. The text is spelt out with metal letters attached to marble panels. This is in a sad state of repair, a number of the letters missing completely and the marble stained, not least from the plants which are starting to encroach upon the monument from the field behind. However, the letters had been attached for so long the weathering of the marble means the shape of the letter is the colour of the stone at the time if the monument’s inauguration in 1969.

A rough translation of the text reads:

“On this road, from Mushqete to Petrele, was decided the fate of the war for the liberation of Tirana. On the 14th and 15th November, 1944 the fighters of the 1st, 4th, 8th and 17th (Partisan) brigades ambushed a German column of 3,000 and exterminated them.”

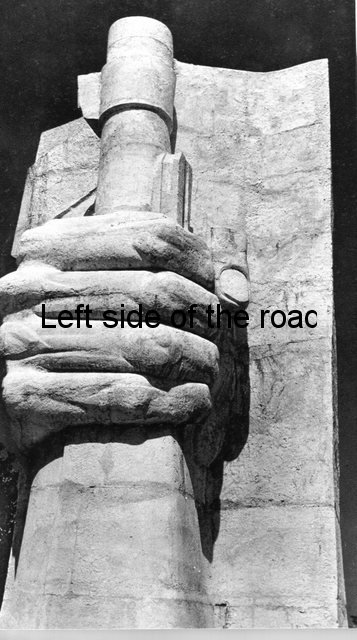

The second part of this monument is completely different in character to the story telling panel. This is a pillar, which must be close to six metres high, depicting a huge human hand holding the top end of the barrel of a rifle.

It stands at right angles to the panel and is facing in the direction of Mushqete creating an L-shaped arrangement. The other panel could possibly have been formed elsewhere and then transported to the site but this column would had to have been made in situ – and presumably this is where the architect Miho comes in.

This hand is so big it begs comparison with the body parts found in Rome, the only remains of the huge statues that once stood in the city when the Roman Empire was at its height. To add the rest of the body to this hand would be to create a colossus indeed. To the best of my knowledge this type of depiction of the Albanian fighter is unique and nothing approaching this sort of scale appears anywhere else in the country.

The largest Partisan statue I’ve seen is the one in the Gjirokastra Castle museum, but even that would be a tiddler beside the giant of Berzhite. The statue of Mother Albania in the National Martyrs’ Cemetery is big but a good half of its height is plinth.

The way I interpret this structure is to consider the size of the hand representing the potential power of the organised working class, being able to swat away the insect that is capitalism with ease, all that’s necessary is the will.

The hand and the rifle look in good condition and the whole of this part of the monument looks as if it had recently been whitewashed, but as with the panel this was not part of the original plan. However, time and lack of decent maintenance since the 1990s has meant cracks are starting to appear at the top of the column, towards the back.

On the flat wall at the back of the hand is the symbol of the double-headed eagle with the star (at the top) and on the flat surface facing the road are the letters VFLP. This is an initialism for “Vdekje Fashizmit – Liri Popullit!” (“Death to Fascism – Freedom to the People!”) a slogan and an oath which Partisans used to express their unity of purpose.

Finally, about the monument itself, in the extreme bottom left hand corner of the panel can be made out the letters H DULE, the sculptor has ‘signed’ his work.

GPS:

N41.252781

E19.89280801

DMS:

41° 15′ 10.0116” N

19° 53′ 34.1088” E

Altitude: 192.2m

How to get there.

Berzhite is on the SH3, what used to be the main road between Tirana and Elbasan. A new motorway is presently being constructed along this route and the long distance buses no longer go along this stretch of road. However, there are two local buses which leave from the bottom end of Rruga Elbsanit, close to the junction with Boulavard Bajram Curri in Tirana. One is signed ‘Lapidar’ which terminates at Mushqete and the other goes a little further to the small and isolated village of Krabbe. The Krabbe bus leaves every half hour, at least in the mornings, at 15 and 45 past the hour. The Lapidar bus slots in between these times. The cost is anything from 50 to 100 lek, depending whether the ‘conductor’ wants to charge local or tourist prices (but as there are 170 lek to the pound (at the end of 2014) either price is not going to break any tourist bank.) The monument is set back slightly from the road, on the right hand side going in the direction of Elbasan, less than 30 minutes from Tirana. The bus going back to Tirana stops outside the cafe and shop opposite the monument.

For an Albanian view of the battle and its aftermath go to What does this monument stand for? The Mushqeta Monument, which is reproduced from New Albania, No 4, 1976.