‘The Sun’ Concert Hall – Palau de la Música Orfeó Català

Catalunya/Catalonia

A collection of posts covering various aspects of the Spanish (although many Catalans don’t want it to be) region. Some of the early posts might now be out of date but are included here for whatever historical merit they might have.

History

The Roman City of Baetulo, Badalona Museum

I’d think I’d be fairly safe in saying that the overwhelming majority of people who visit Barcelona aren’t there for what remains from the Roman period – many not being aware that the Romans had actually been there in the first place – most coming to view the Modernist architecture of the likes of Antonio Gaudí and Lluís Domenech i Montaner. That’s a shame as the city has remnants from 2,000 years ago, although admittedly some of them need to be searched out. Even fewer people would be aware that just a few kilometres down the Metro line to the north-east of Barcino (the Roman name for Barcelona) is the Roman City of Baetulo at Badalona Museum, one of the most important Roman archaeological sites in Catalonia.

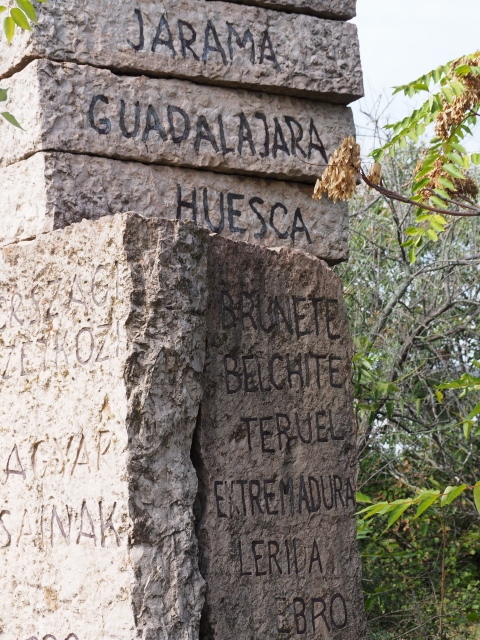

The Spanish Civil War

Refugi 307 – A Spanish Civil War air raid shelter in Barcelona

Refugi 307 (an air-raid shelter during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39) is one of the few existing shelters from that conflict which it’s possible to visit. Situated in the working class district of Poble Sec it’s very close to Montjuic Hill. The opening of these places to the public throughout Catalonia was part of a project called Memorial Democràtic, started under a more left leaning regional government. The right, who’ve regained control of Catalonia, have messed around with the organisation and I’ve found it impossible to discover exact details of the present state of affairs. This shelter is now under the control of the Museu d’Història de Barcelona.

The air raid shelter of Placeta Macià, Sant Adrià de Besòs

The air raid shelter (refugi antiaeri) in Placeta Macià, Sant Adrià de Besòs, Barcelona, provides an insight to what life was like for ordinary, working class, people during the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39.

Rosanes – a military airfield during the Spanish Civil War

Memorial Democratic, a programme to spread information about the history of the Spanish Civil War, tells the story of the small Republican airfield of Rosanes, just outside La Garriga in the hills just to the north of Barcelona, Catalonia.

Modernismo

Santa Creu i Sant Pau Recinte Modernista

The largest, and in many ways the most impressive, of the Modernist sites in Barcelona, indeed in all of Catalonia, is probably also one of the least known and visited. This is the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, designed by the architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner who was also responsible for the Palau de la Música Orfeó Català.

Arenas de Barcelona – Placa de Espanya

Arenas de Barcelona, the bull ring right next to one of Barcelona’s busiest roundabouts at the Plaça de Espanya, had been closed for years. Bull fighting has its supporters throughout the Iberian Peninsular but it never had such a fan base in Catalonia as it did, and still has, in the likes of Andalusia and Extremadura. Come the 1970s and it’s owners considered it wasn’t a viable concern. For bull fighting fans that wasn’t such a total disaster as there was another large ring only a few kilometres east along the Gran Via de Les Corts Catalanes at Monumental.

Palau de la Música Orfeó Català – Barcelona

If you have any interest at all in Modernisme (the Catalan name for what is called Art Nouveau in Britain) then any visit to Barcelona has to take in the unique Palau de la Música Orfeó Català at the Via Laietana end of the narrow Sant Pere Més Alt. The work of the Barcelonan Moderniste architect, Lluís Domènech i Montaner (whose other great monument to Modernism is the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau) this one building encapsulates all the aspects which arose time and again in the short 20-30 year period of Moderniste dominance which straddled the 19th and 20th centuries. Love it or hate it you can’t ignore it!

Casa Barbey – A Modernist summer house in La Garriga

Modernism is not restricted to Barcelona as many towns throughout Catalonia boast at least a few examples of this late 19th early 20th century architectural style. La Garriga, about 30 kilometres north of Barcelona, developed as a spa town at the same time as the heyday for this fashion and Casa Barbey is one of the best examples in the town.

Architecture

There’s been an open air, general and for a lot of the time unorganised and unregulated market in the area of Las Glories of Barcelona for centuries. Even though I’ve been to Barcelona many times over the last 20 plus years I’ve never made it to that place until this year (2015) – which might be a shame (in retrospect) but then shopping and markets ave never been my thing and my experiences of walking through the Madrid Rastro (never with any serious negative consequences (it’s a pickpockets and general thieves paradise) but coming away wondering why I had gone through the experience of jostling through thousands of people when there was never anything I might have wanted to buy). But I was glad that on my most recent visit to Barcelona I made it an effort to go to Els Enacants Vells, at Plaza de Las Glories.

San Joan de Reus University Hospital

Innovative modern architecture is evident in the recently opened San Joan de Reus University Hospital, on the outskirts of the city in the southern part of Catalonia. This is yet another example of where the countries of Europe lead the way when it comes to modern architecture.

Mies van der Rohe Pavilion, Barcelona

If, after a few days in Barcelona, you’re suffering from a surfeit of Modernism (too much Gaudi or Domenech i Montener) then you could do much worse than visit the Mies van der Rohe Pavilion in the exhibition and conference area, between the Plaça de Espanya and the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

Catalan Culture

The Castellers de Sant Adrià de Besos, Barcelona

Anyone who has travelled around the not totally foreign tourist dependent areas of Catalonia in the summer months might well have come across a group of castellers, the people who construct human towers which vary in height and complexity dependent upon the number, size, experience and expertise of the colle (group). I’ve only seen these towers a few times in real life (although quite a number of times on the television – a similar experience I have to bull fighting) and didn’t really understand much about the practice until I had the chance to attend a practise session of a group that has recently been formed, the Castellers de Sant Adrià de Besos, Barcelona.

Thirty or so years ago Platja d’Aro was just a quiet village on the northern coast of Catalonia. With the development of tourism and the creation of the ‘Costa Brava’ the town mushroomed and now is predominantly a place of hotels, apartment blocks and summer homes for the Catalan wealthy. From the end of the summer season in September/October until Easter the following year the place reverts to its original population levels, summer homes being closed for the winter. Apart, that is, until it’s time for the Platja d’Aro Carnival.

Carrers Guarnits in the Festa Major de Gracia, Barcelona, 2012

Every year the Barcelona district of Gracia organises a street based competition during its Festa Major in August. The carrer guarnits (decorated streets) are a tradition going back just under a hundred years and attracts visitors from all parts of the world.

Eating and Drinking

Can Joan, Carrer del Lleo, Badalona

It’s good to travel alone as it’s possible to take the credit for every achievement but from time to time it’s relaxing to go to a place where you know people who know people. Through this network I had been given a guided tour of Baetulo (the Roman town that pre-dates anything in Barcelona) in the Badalona Museum. Not only that our guide recommended a place near-by to eat and that’s how, on a Wednesday afternoon at the end of February, I went for my lunch in Can Joan, Carrer del Lleó, Badalona.

El Glop – Taverna del Teatre – Barcelona

I had just walked around L’Eixample for three hours or so, following a route that took in various Modernist buildings, and finished down by Plaça Catalunya. I had originally planned to head off to a restaurant recommended in one of the guide books but couldn’t find it on my map and, anyway, it would have been another 10 minute or so walk so decided on one that I passed just before the end of my itinerary El Glop – Taverna del Teatre (the theatre in question being Tivoli cinema house).

Le Nou – Restaurant – Barcelona

If you’re going to eat one main meal of the day in Catalonia the best you can do, in terms of value for money and often in terms of quality, is to go for a ‘Menu’. Although in a place like Barcelona they are used to foreign tourists the pronunciation of this is phonetic, no fancy messing around with the ‘n’ as if it were a Castilian ‘ñ’.

Contemporary Calalunya/Catalonia

As a referendum about Scottish Independence approaches I thought it would be useful to hear about another region of Europe that wants the same thing, Catalonia wanting to separate from Spain. Here are the ideas of a Catalan from Barcelona.

Charity from the Catholic Church or asking for other hand-outs is the suggested way out of the crisis in Catalonia, according to a judge. In Britain and the US the answer is in the growing number of ‘Food Banks’ to provide emergency food aid.

One o’clock in the morning – La Rambla, Barcelona

The Rambla in Barcelona is considered to be one of the ‘must’ places to visit if you are in the city. Publicity pictures and videos will show you hoards of smiling people, brightly dressed, relaxed as they take in the sun at the same time as they take in all the sights the Rambla has to offer. There are cafés aplenty, the human statues (although they were strangely absent when I was there recently), the smell from the flower stalls half way down, the artists waiting to paint your portrait down at the bottom end. But a different form of tweeting now comes from the part of the Rambla where the bird sellers used to be based, the sale of wild birds having been banned since 2010.

IVA increases – small businesses cash in

The level of Spain’s purchase tax (IVA) went up on many goods from 18% to 21% on September 1st 2012. Are small businesses cashing in on this increase and causing inflation in the cost of some of the most basic of everyday purchases?

La lucha continua becomes La lluita continua

The practice of storming supermarkets, filling trolleys with the basic necessities of life and then leaving without paying is spreading. After starting in a couple of places in Andalusia groups with a similar agenda have carried such activities in Merida, Extremadura and most recently in a town in Catalonia.

‘Privatisation’ of Parc Guell?

The Barcelona municipal council are considering charging admission for entry into Parc Guell, one of Antonio Gaudi´s gems, in order to get more money from visiting tourists, without improving access or services. This is opposed both by tourists and the local residents.

Walking in Catalunya/Catalonia

Montseny Natural Park and the Congost Valley

The Montseny Natural Park, just to the north of Barcelona in Catalonia, contains a wide variety of flora and fauna and offers many opportunities for the walker. On its western edge is the Congost Valley, historically one of the escape routes for those fleeing the Fascists towards the end of the Spanish Civil War.

Els Tres Monts – Stage 1 – Montseny-Tagamanent

Els Tres Monts (The Three Mountains) is a waymarked route from the village Montseny (in the Natural Park of the same name) to the hilltop Monastery of Montserrat. In the process it passes through the Sant Llorenç del Munt I L’Obac Natural Park affording an opportunity to experience the diverse landscape in this part of Catalonia, from soaring peaks to sheer cliff faces, from Romanesque churches to Modernist extravagance, from large farmhouses to peasant cottages.

Els tres monts long distance walk starts in the village of Montseny and over a (suggested) period of six days arrives at the mountain top Monastery of Montserrat, 110 kilometres away. On the way you pass through a varied countryside and after some steep climbs you arrive at other sanctuaries seemingly stuck on to hill tops, offering views of the natural parks and as far as the Pyrenees.