Facade of Vlora Palace of Sport

More on Albania …..

The bas reliefs and mosaics of the Vlora Palace of Sport

Although they are being neglected, and sometimes need dedication and determination to view them, there are still a number of artistic works from the Socialist period on many of what would have been public buildings. The most impressive (and becoming one of the most neglected) is the grand mosaic on the facade of the National Historical Museum in Tirana. Another example, which can easily be missed, is the bas-relief on both the north and south sides of the Palace of Sport in the town of Vlora. Even more easily missed are the two interior mosaics on either side of what would have been, in the past, the main entrance to this sports centre.

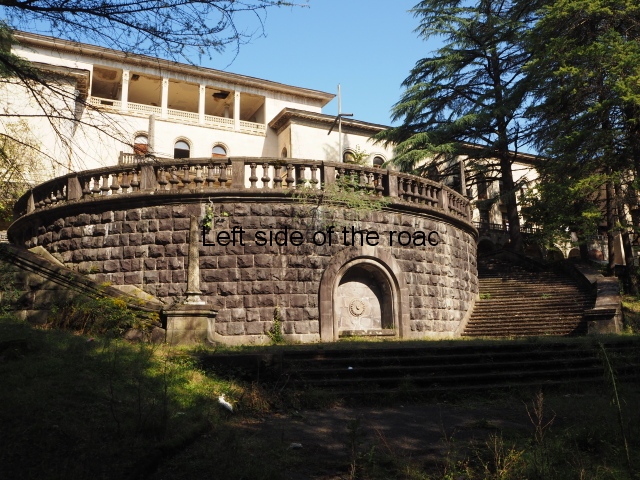

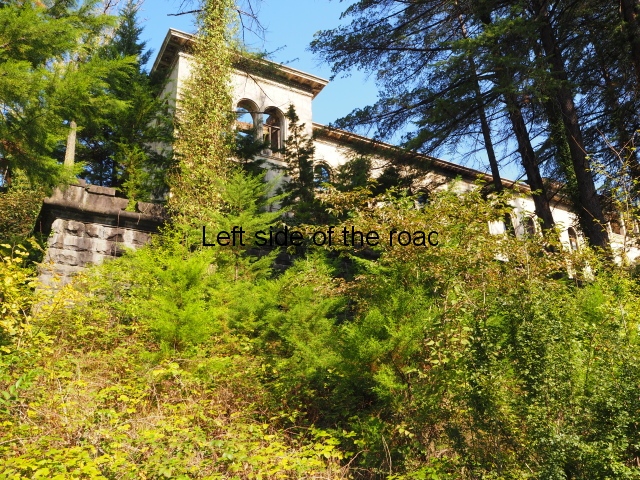

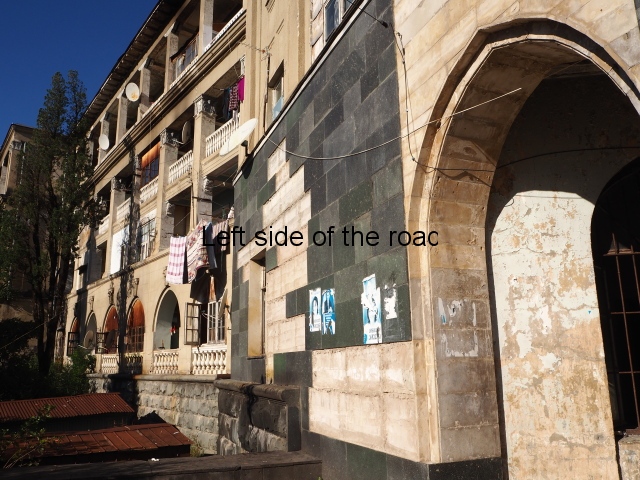

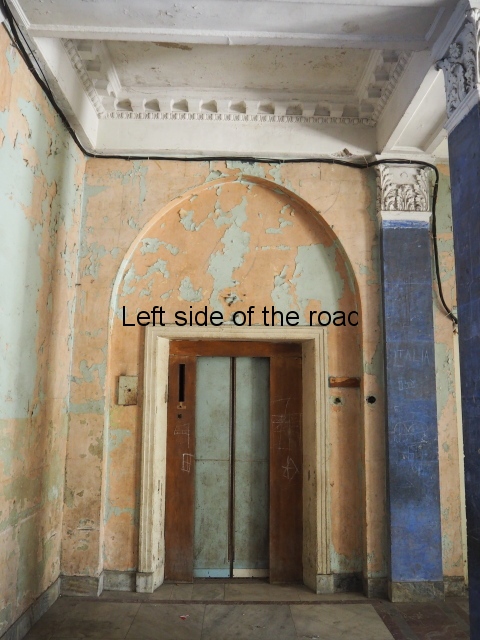

The Palace of Sport (now the home of the town’s basket ball team, Flamurtari – the same name as the football team whose home ground is in the long-established stadium less than a hundred meters from the hall) is located at the bottom end of Rruga Sadiki Zotaj, the main street running from north to south through the town, at Sheshi Pavarësia (Independence Square). Although the facade, and the square in front of it, has had some cosmetic work done in recent years the money seems to have run out for any further modernisation of the interior of the main entrance. For this reason, to the casual visitor, the building looks abandoned – like so many public buildings dating from the 1970s and 80s – with graffiti scaring the white paint work and entrance to the court is now at the back of the building.

Flamurtari signifies ‘flag bearer’, not in the personal sense but in the figurative sense. Vlora ‘prides’ itself as being the town where formal independence was declared in 1912, hence the very large monument to the event at the northern end of the main street. So it’s the town that is the standard-bearer. This was emphasised during the time of Socialism but now gets formal acceptance by most of the so-called ‘democratic’ political parties whilst they preside over the very real giving away of that very independence so hard-fought for. For the workers and peasants the day of true independence was achieved on 29th November, 1944, when the Fascists were defeated throughout the country. That celebration is now sidelined and ignored by the bourgeois parties as it would mean a recognition of the role of the Communist Partisans in the National Liberation War.

The Bas Reliefs

Southern Bas Relief

Of the two the bas-relief in the best condition is the on the southern face of the building, on the right as you look at the main entrance. This is probably solely down to the fact that it looks down upon one of the expensive bars attached to one of the hotels that are mushrooming throughout the country. The bas-relief is high up and as with all such of the Socialist period it tells a story.

Starting from the bottom we have a number of athletes taking part in various sports, both representing sport in general as well as some of the activities that would have taken place in the building. On the extreme left is a male in the act of about to throw a discus. Next are two males wrestling. These images represent those sports that were practised in classical antiquity to date.

Matters are brought up to date with the next images of two females. One is in the act of leaping to throw the ball, clasped in both her hands, into an unseen netball ring. Her opponent is also leaping, her right arm high above her head, in an attempt to prevent the goal.

Next in line is a return to antiquity with a male with his back to us. His right arm is stretched behind him and in his right hand the he holds the shaft of a javelin. He is running forward and the tension can be seen in his body as he is just about to put everything into his throw. Finally, amongst this group, we have another female facing towards the back of the building. She has her arms outstretched, her right leg raised and bent at the knee whilst she stands on her toes on her left. The element of grace in this image indicates that she is a gymnast, following a floor exercise.

There is a suggestion of gender difference here as the males are involved in trials of strength whilst the women are following those sports which in the past were considered more appropriate for females.

This traditional idea is challenged somewhat in the image above the first group. Here we have a group of ten runners, seven male and three female. The fact that the two genders are introduced in the same race seems to indicate that here is represented something akin to the modern-day marathons where gender plays no role in the entry qualifications. It also represents athletics in its purest and most basic, running needing no special equipment – despite what the sports manufacturing companies spend a fortune in promoting.

The three women are at the back of the group and for some reason one of them is actually looking backwards. As they are all running at full pace this is difficult to explain. The only time an athlete would be looking backwards would be at the time of changeover in a relay race but this doesn’t make sense here.

The idea of any gender difference gets blown out of the water in the final panel on the left hand side of this bas-relief. Here we have a group of five standing males (with their left legs forward) and four kneeling females (their right knees on the ground, the foot being bent, whilst the left leg is bent at the knee and the foot firmly place on the ground for stability) all in the act of firing, or about to fire, their weapons. The rifles are pressed against their shoulders, their left hands on the barrel and their right fingers on the trigger.

Rifle Practice

The figures are presented in a row, the one behind slightly in front of the one before, the symmetry of their stance being demonstrated by the left legs of the males stepping forward and the left, bent, leg of the females. This all gives an impression of depth on a flat plane.

As is almost always the case in Albanian Socialist Realist Art there is an indication that Socialism is something that represents all the people, from whatever part of the country they might come call their homeland, whether they be peasants or workers. The male closest to the viewer is dressed in the jacket and hat that is most associated with the mountains. He also seems to have a brez (a wide cloth belt) around his waist, as seen on the statue of Bajram Curri in the northern town which bears his name. We only really see the heads of the figures behind the first but all the faces are different and they all display different characteristics but it’s not easy to define ethnicity. What can be seen is that two of the others are wearing caps, the last two being bare-headed.

From the images of the women we can get no idea of their background, all of them being dressed in what, at the time, would have been, more or less, the uniform of the militia. This, for women, meant a step away from tradition as although it might be very attractive in its own right such clothing was not entirely practical for modern warfare – although there are images of fighting women in traditional clothing in lapidars such as the Arch of Drashovicë. All four of the women are wearing caps and we can see the long hair of the female closet to the viewer.

Here I don’t think that the rifle shooting is being introduced as a sport as it might be considered nowadays. However there is a link between sport and the armed militia. Physical activity would have been encouraged during Socialism and such Palaces of Sport built in all towns and villages to promote the well-being of the people. After centuries when the vast majority of the population would have been living a subsistence existence the last thing on the minds of the ruling class would have been the promotion of a strong and healthy working class or peasantry – especially one that knows how to use modern weapons. On the other hand a Workers’ State depends upon an armed and trained militia to defend itself against the many attacks made by the defeated capitalists.

(Witness the hysteria in capitalist countries about any weapon in the hands of ordinary people whilst at the same time the state spends billions on weapons which are accessible only to their puppet armed forces in times of conflict – which can just as easily be used against their own population if the workers ever decide to get up off their knees and oppose oppression and exploitation.)

When it comes to nutrition things haven’t changed a jot in the present day. The cheapest foods available in the vast majority of countries tends to be the most unhealthy in the short and long-term. Just consider the proliferation of fast food outlets throughout the world and in present day Albania the cheapest food is the fatty meat and ‘E’ numbers laden sauces that make up sufflaqe, or its local variants.

It has to be remembered that military service was obligatory for all young people in Albania during Socialism and there is no point in having weak and sickly soldiers (of whatever gender) to defend the homeland. The poor health of so many young men after a century and a half of the Industrial Revolution in capitalist Britain showed how badly the working class had fared in that time and was dramatically demonstrated when they were expected to go to the front in the murderous, imperialist war of 1914-19 (euphemistically called the ‘Great War’ by some).

Another aspect that should never be forgotten, and a matter I have constantly stressed when writing about Albanian Socialist Realist Art, is that in these images the women are armed. Armed with modern weapons but also with an ideology that uses that armed force for the benefit of women within the general society. So far, on this blog, when describing the lapidars, when weapons are an integral part of the image, the only one where the women have NOT been armed is on the bas-relief in Bajram Curri, a later piece of art which, in some ways, presaged the future.

Even though armed and provided with more equal rights than in any other country worldwide the Albanian women, just like the men, threw away those conditions in favour of short-term material gains and so-called bourgeois ‘freedoms’. This has led to the present situation where the country has lost any semblance of independence and with an economy that is totally at the whims and mercy of international financial interests and investment.

Although the primary focus of this bas-relief is towards the front of the building, looking from right to left, the firing men and women are directing their anger towards the back of the structure, otherwise they would be shooting their comrades in the back.

All of the images so far have been placed on a background in the shape of a lower case J. I have tried to work out the meaning of this but without success. Working on the basis that all aspects of such a work of art mean something this one has got me beat.

What is relatively clear, however, is the grouping of the flags at the top of the image, above the sporting and military figures. There are an uncountable number of them, at the top of flag poles whose serried ranks again give an impression of depth. However they are fluttering in both directions. This is obviously impossible. As I’ve stated elsewhere Socialist Realism doesn’t mean realistic imagery, it’s allegorical and attempts to tell a story in a new and innovative manner.

Banners above the military

One interpretation of this image is that it’s a transitional stage to what we see as part of the main image to the left, that they are leaves of a book and, by extension education in general. Sporting expertise without education just provides society with such as the rich, mindless and illiterate footballers in the modern game, unable to string two words together in any known grammatical structure. Being able to kill people without an understanding of the political situation in which this killing takes place only produces mercenary killers and not liberation fighters.

The main subjects of this bas-relief are two athletes, a man and a woman, running flat out, their legs as wide apart as is possible when in a race. They are running on the bottom curve of the ‘J’ and their hands reach as high as the flags. There’s obviously a classical reference here, the only difference being that the two figures are clothed, the man with shorts but bare-chested whilst the female wears shorts and a T-shirt (female public nudity not being an element of Socialist Realism). On their feet it is easy to make out that they are wearing running shoes.

They are runners but not only runners. Within this image there are a number of ideas. We have the fact that they are healthy and fit, capable of strenuous activity that is not connected with work but for pleasure.

The woman is closest to us. She has her left arm fully outstretched behind her and her right arm is fully extended above her head. In that right hand she holds a rifle close to the end of the barrel, the rest of the weapon hidden by her arm and body. Her face is in semi-profile and her long hair flows out behind her by the force and speed of her forward movement.

Allegory of Socialism

The male is partially hidden by the female. His left arm is fully extended above his head, parallel and just behind the right arm of the woman. His hand grips the handle of a pickaxe just where the shaft meets the metal cross-piece. To all intents and purposes the rifle and the pickaxe are touching. This is in reference to the revolutionary slogan of the Party of Labour of Albania ‘advancing towards Socialism with the pickaxe in one hand and the rifle in the other’. This is interpreted as meaning that work alone will not achieve Socialism unless it is protected by the same level of force of those capitalist and imperialist forces who seek to deny working people the control over their own lives and the wealth of their country.

As if it is not enough to run with a heavy pickaxe held high he is also carrying a large book in his right hand, pressing it against his waist.

The whole combination of elements surrounding these two young people is an attempt to show how the society – at the time of its creation – was going forward towards Socialism. This relief was almost certainly inspired by the statue of the ‘Worker and Kolkhoz Woman’ (1937) by Vera Mukhina, presently situated at the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy in Moscow.

This bas-relief is in a good condition and it looks like it has very recently been cleaned and repainted. As I’ve already stated it faces down on a fancy cafe attached to a new 4 star hotel. It’s good that this ‘public face’ has been respected – but as so few people actually look up higher than their own eye level I don’t know how many have actually noticed this unique and interesting piece of history.

Unfortunately fate has not been as kind to the mirror image that is in a similar location on the north side of the building. I say a ‘mirror image’ but that’s not quite the case.

Northern bas-relief

Most of the elements on the south facade are repeated but with a few minor differences. On the bottom panel where five different sports are represented, new ones have been inserted. From left to right we have; discus throwing, weight lifting, netball, wrestling and a female gymnast. Those which are repeats are the same as on the south side apart from the stance of the gymnast. She is still engaged in a floor exercise but here her left leg is on the ground, her right leg raised high behind her. Her right arm is raised high above her head and her left stretched out behind her with her head bent back.

The weight lifter, a male, looks like he has just achieved success in the jerk technique, his left leg bent and his right out behind his body, providing the balance.

The running group above is also slightly different. It’s still a mixed gender group, bunched up as in the early stages of a distance race but this time there are only seven runners.

At the front are two males running almost together, there being little seen of the runner behind apart from his legs. The runner fourth – as is the one in fifth, sixth and seventh – place is a female, we know this by their long hair, flowing behind them. It’s impossible to make out any of the facial features of the runner in fourth due to deterioration of the image.

Long hair for males wasn’t common in Socialist Albania and the press and governments of the capitalist west made a big issue of this in the 1970s when visiting young people were ‘obliged’ to have a haircut at the border if they wanted to get a visa. Whether this was more of an urban myth, promoted to denigrate Socialism, is more than likely it being almost impossible at that time to arrive at the border and obtain an entry visa – very much like it is at present on seeking entry into the belly of the capitalist beast, the United States of America. Stones and glass houses comes to mind.

Anyway, the length of the hair is still the clue to the gender of any person on any public Albanian art from before 1990 – their being no comparative artistic endeavour produced under capitalist controlled Albania. That’s not a surprise, how can you represent the idea of hope and a future when the measure is the amount of material goods one has and in a system that is prone to economic crisis. The image of a rich man or woman surrounded by all they can possess would be seen more as a parody rather than an aspiration for those without anything.

In the panel that shows both men and women firing rifles the stances are very much the same, the men standing and the women kneeling, but here the number of women has been reduced to three whilst the men stay at five.

However, the ethnic element is still present with the male who is most visible being dressed in a traditional country jacket and hat whilst the other four sport modern caps or go bare-headed.

The arrangement of the flags is the same and the only significant difference between the two main characters of the story is that what they held in their right hand on the south facade they now hold in their left, and vice versa.

Deterioration to north facing bas relief

As I’ve stated before his bas-relief is not in as good a condition as the one on the other side of the building and hence is sometimes difficult to read clearly. It’s north facing and doesn’t get the same amount of sunshine and that has led to a proliferation of black mould. Lack of cleaning and maintenance also means that the plaster is starting to come away in places. This deterioration is quite noticeable in the five and a half years between my visits to the Vlora Palace of Sport. It also suffers from looking out over a dusty, dirt car park and probably not noticed by the vast majority of people who might pass by. A little bit of tender loving care wouldn’t go amiss – although I think that’s highly unlikely to happen in the near future.

Of the artist I have no information whatsoever. Normally such works would have been created by local sculptors, especially in the late 1970s early 80s when I estimate this building was constructed. But who I have yet to discover.

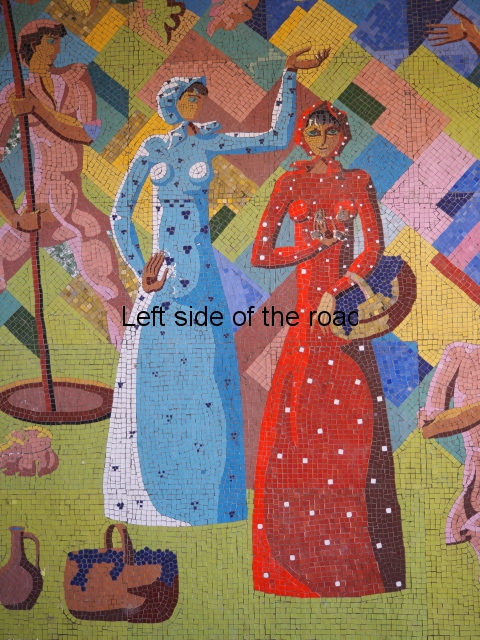

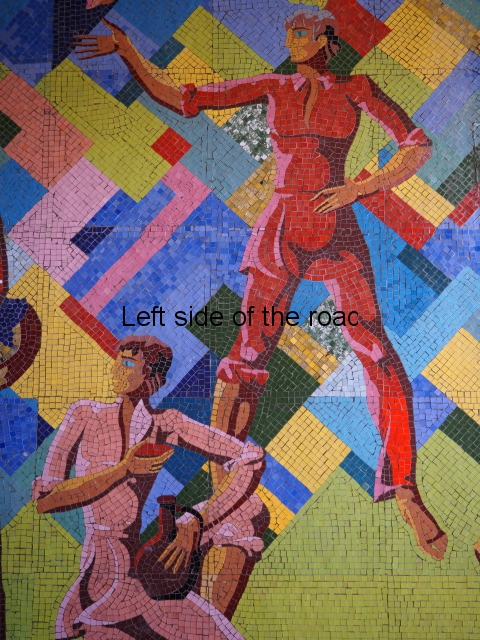

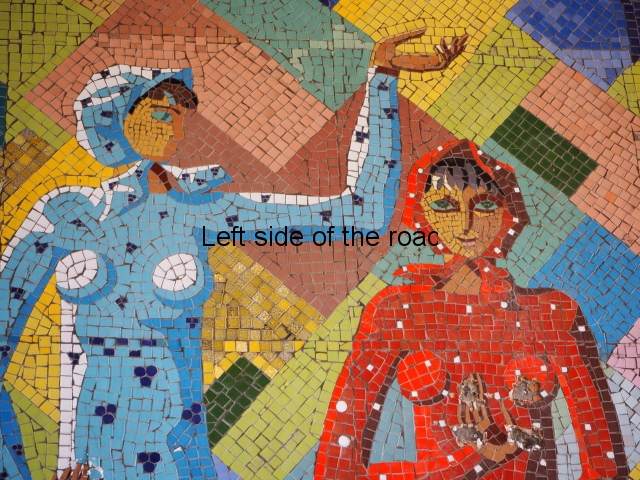

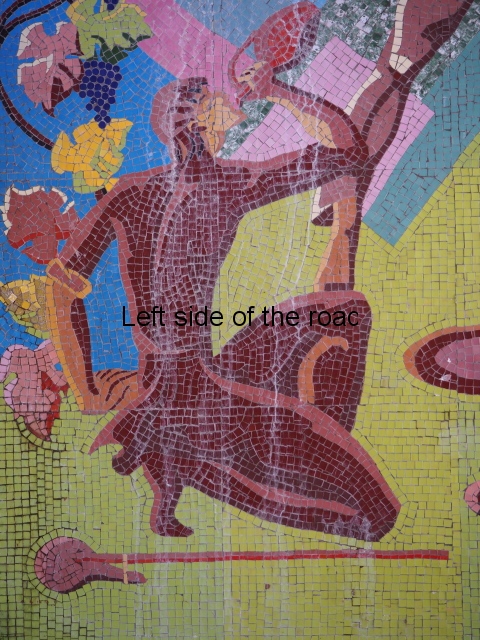

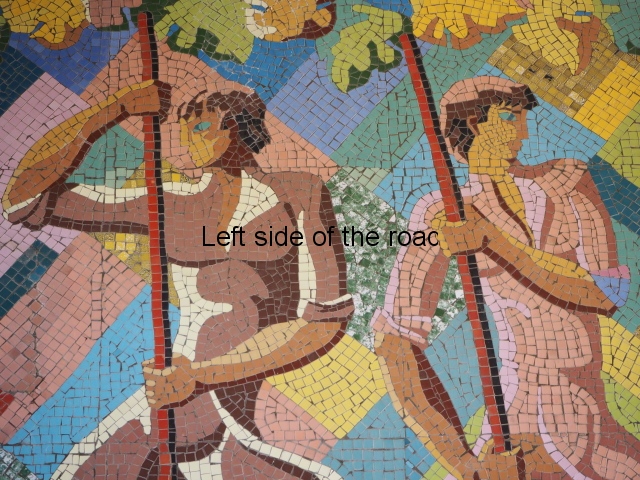

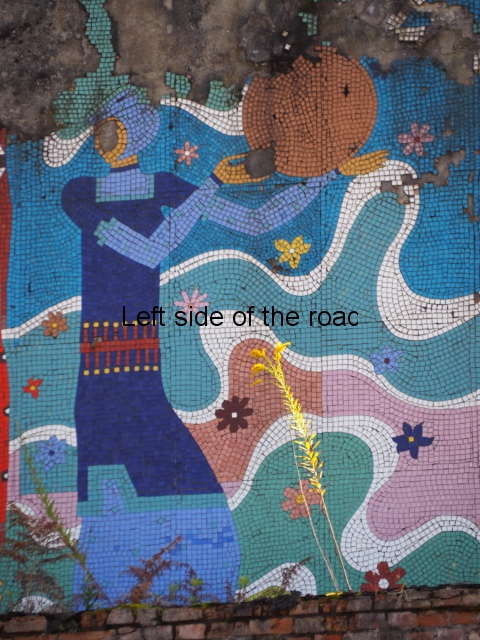

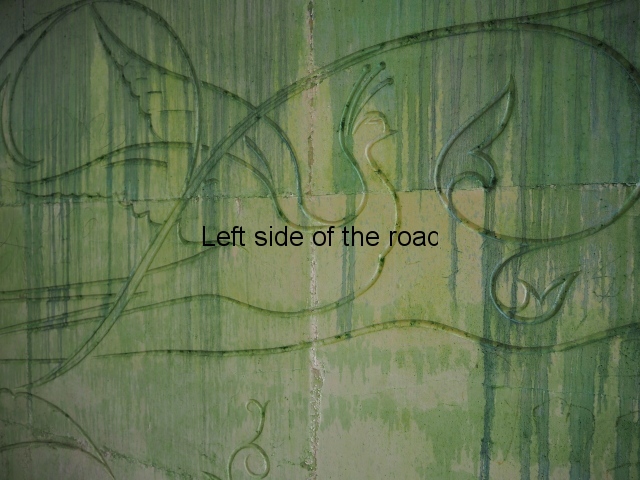

The Mosaics

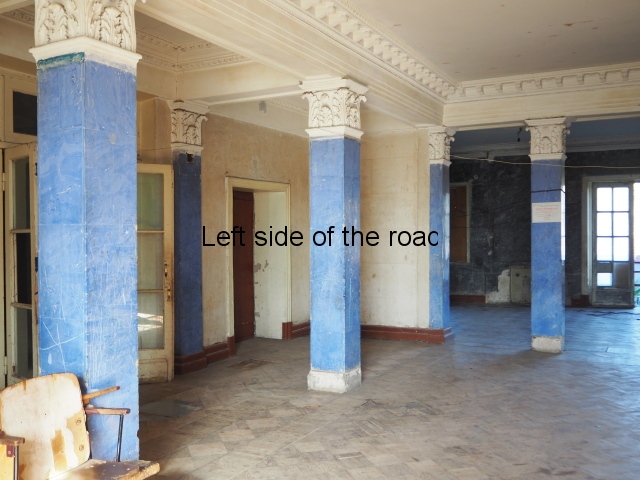

Traditional Sport

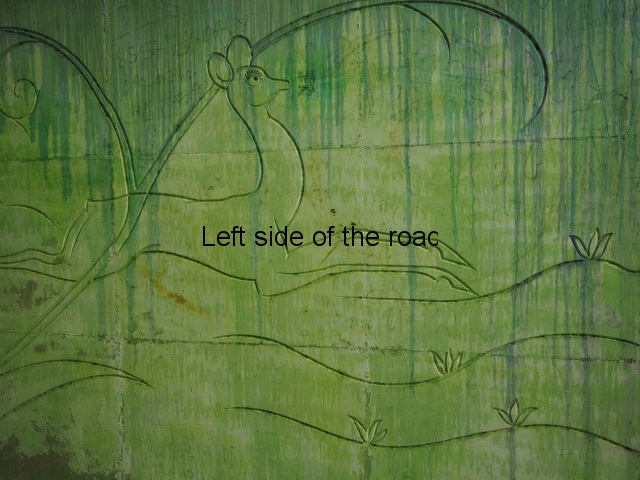

To appreciate the bas reliefs you only have look up from the street when passing by, close to the ferry port. However, there are a couple of gems that can only be seen by looking through the dirty windows of the unfinished renovation of the main entrance hall to the building, fronting on to the main street.

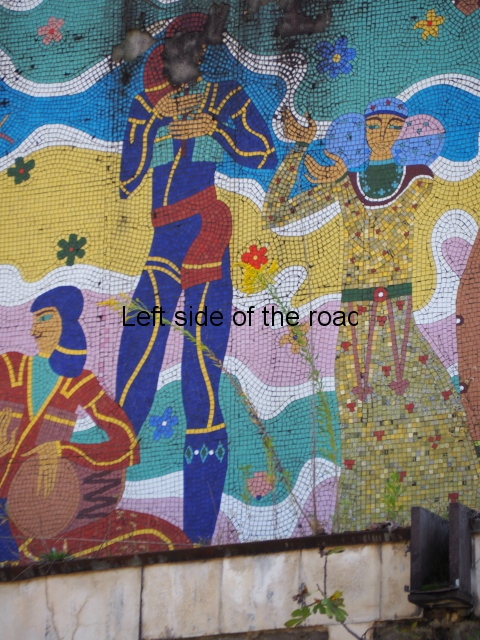

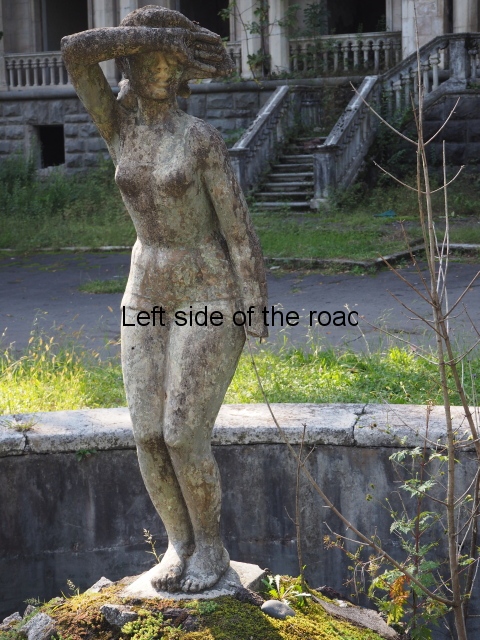

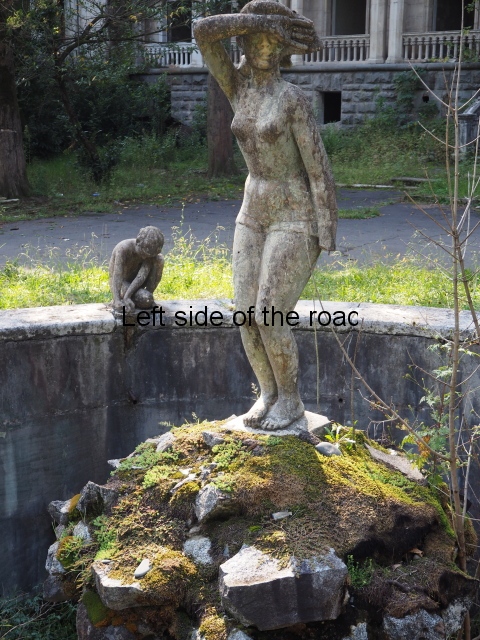

These are two mosaics which tell the story of the development of sport in Albania from the period in the past when ‘sport’ used the technology available at the time to the late 20th century when sport became much more of an organised activity.

The first mosaic is seen inside the left hand entrance to the building. Here all the individuals are dressed in the everyday clothing of the peasantry up to the end of the 19th century. They are engaged in what we now call sport but would have been more a form of local entertainment in the past, as well as competition between the young men to attract the attention of the nubile women as has been the case in tribal societies throughout the world for millennia – there’s only one woman portrayed on this mosaic but she is there as part of a political statement rather than a participant in competitive activity.

This last statement is not made as a criticism of the imagery on the mosaic. Women were involved in the actual fighting against foreign invaders from very early times. This was especially the case from the late 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. The ‘People’s Heroine’ Shote Galica, who is often depicted in photos as heavily armed as any man, died young (at the age of only 32) and was a virtual legend in her time. She was commemorated during Socialism by the marking of her grave in Fushe-Kruja and a large bust of her in Kukës.

The involvement of women, especially those we now call teenagers, in the struggle for the liberation of their country increased exponentially in the anti-fascist liberation war – the example of Liri Gero and the 68 young women of Fier being a fine example. Many fine young women of Albania fought and died for their liberation – one of the reasons their sacrifice and effort was celebrated during Albania’s Cultural Revolution and on lapidars throughout the country.

The ‘progressives’ in capitalism ‘celebrate’ when women crash through the ‘glass ceiling’ – when most of them do exactly the same as the men in the positions they achieve, that is make capitalism function at the expense of the workers and peasants (just refer to the experience under of Golda Meir, Indira Gandhi or Margaret Thatcher). True ‘female liberation’ occurs when women use their bravery, initiative and ability to wield a weapon to gain their freedom and in so doing aid the liberation of all the oppressed and exploited – as happened in China and Albania.

Back to the image. In the top left hand corner there are two men standing and facing one another. Their elbows rest on a flat surface and their right hands are clasped together. They are arm wrestling. The image I have in mind with this activity (for no other reason than this is how it is normally depicted in cinema) is that they should be sitting but, it seems, in Albania it was carried out standing up. But what more simple a test of strength can you get? One on one, no technology involved, and can be carried out anywhere.

Arm Wrestling

As with the majority of the men on this mosaic they are dressed (starting from the top) in a qeleshe (felt skull-cap), xhaqeta (waistcoat), tirq or brekusha (trousers, sometimes tight, sometimes loose), brez (cloth belt), corape (long socks) and opinga (the shoes that have a ball of sheep skin at the toe to keep the water out – this might be more familiar to those who have seen pictures or the reality of Greek ceremonial soldiers) and in all cases here the balls have been dyed red.

Below them, on the left hand side, is a group of men all huddled together in what looks like a rugby scrum. It can’t be a contact game as they are all wearing loose clothing and that’s definitely a disadvantage if you are going to be chased (and a felt qeleshe is certainly nothing like a modern rugby protective cap). But, so far, I’ve been unable to come across a credible explanation of what they are doing.

Next to them is another conundrum. Here we have a young boy with a rope. If you look carefully you can see there’s a loop in the end of the rope that he holds in his left hand. This is reminiscent of a lasso, but that doesn’t make sense (at least to me) in a society where the principal domestic animals were sheep and goats – not much challenge, surely, in lassoing a sheep? It doesn’t appear to be a skipping rope as if the artist wanted to depict skipping surely s/he would have shown the boy actually jumping in some way. (Here I’m suggesting the artist might have been a woman, however, from what I’ve learnt so far about Albanian Socialist Realist art (of whatever kind) there seems to have been a dearth of women artists. Yes, the role of women was to be celebrated but by works created by men.)

This young boy is dressed slightly different from the men so far described. Most Albanian Socialist Realist works represent people from different parts of the country and this boy is wearing a fustanella, the skirt like attire worn by males (again familiar to those who have seen Greek state ceremonies) and more common in the south of the country.

Whatever the sport it was something that was still common during the period of Socialism. Inside the entrance at the back of the building is a statue of a young woman, this time, swinging the rope above her head.

Female Athlete with rope

Two central figures dominate the mosaic. One is a male who is on the point of loosing an arrow from his bow. Although the bow and arrow was the precursor of the gun this weapon doesn’t appear that often in the imagery of the late 1960s to the mid 80s. Yes there are a lot of them shown on the murals in the Skenderbeg Museum in Kruja and might appear as the accoutrements of war in other images, but rarely as a truly aggressive weapon of war. And the Kruja murals are a relatively late addition to the pantheon of Socialist Realist Art and appeared at a time when the politics in the country were starting to undergo major changes.

(If we go to the National Historical Museum, there is only one bow and three arrows on display, indicating it wasn’t that common a weapon of war. The rest of the fighting relics are heavy axes, spears or halberds or pole-axes. Warfare in those times wasn’t in any way sophisticated, you won the battle if you were able to bludgeon to death more of them than there were of you.

For me the cheapest weapon of choice in a mountainous country is the sling shot or the hand-held catapult. Simple to make, as cheap as the surrounding materials, i.e., free, and deadly as any modern rifle in the hands of an expert. David slew Goliath with a pebble and in the early days of the armed struggle of the Communist Party of Peru in the 1980s a sling shot took its toll on the enemy. Or just drop a stone from a great height, images of such activity being common throughout the art galleries of the country. Any guerrilla army uses whatever is to hand to defeat the enemy, the enemy’s technology often being its weakness more than its strength in unfamiliar circumstances.)

He is also dressed in the traditional clothing of the time but with a very loose and long flowing sleeve. Now I’m no expert in archery but I would have thought flowing sleeves are not the type of clothing to be wearing in a war like situation. And if you are going to choose the bow and arrow as your weapon of choice it would seem to make sense to protect the very vulnerable fleshy part of the forearm. The British archers who were so crucial to the victory over the French at Agincourt in 1415 knew this and had leather arm guards.

I don’t think I’m nitpicking on this issue. Socialist Realist Art is not real representation of an event or situation but at the same time it can’t go so far from reality as to cause a suspension of disbelief. As I suggested in the post about the bas-relief in Bajram Curri the greater the period of time between a revolution and its depiction the greater will be the disparity between the image and the accepted reading of the event shown.

The debate about what is truth in history will go on for many more years than I will be around and ultimately depends upon the perception of the victor. If the victor historically is ‘defeated’ many years later then we are into a different ball game. The ‘re-writing’ of history has been going on for a long time and takes place today. However, in a Socialist society which is attempting to write a history for the working people it is incumbent upon artists to get the ‘facts’ correct. After all, however little they might be receiving in recompense compared to their contemporaries in capitalist societies they live a better lifestyle than the vast majority of the working people.

This is not necessarily wrong if they are doing their job because the task they have been given is an important and crucial one. If they are opportunist and just seek an ‘easy life’ they are no better than those artists in history who produced works of art, of whatever quality, for a patron who ‘paid the piper and called the tune’.

It is for this reason that what we can call ‘intellectuals’ have a responsibility over and above that of the vast majority of those in a Socialist society. They are privileged in a way no other section of society is or can be. For that reason they have to be held to account in a way that is different from the majority of people. With rights come obligations. Intellectuals have never understood this and this is why they will always have supporters in the capitalist/imperialist countries. Not because they believe in artistic freedom, just the opposite. They just use this myth of ‘freedom’ to challenge any attempt to undermine their control of the world’s wealth and peoples.

This is a call for intellectuals in any future society to know their place, to take pride in the privileged position they hold and to stay faithful to the people who have put them in that position.

Armed Resistance

The woman is shown with a rifle to her shoulder and she is in the act of firing in the opposite direction to the male, that is towards the right edge of the panel. This is not a modern weapon but something that would have been around during the middle to the end of the 19th century, having a much longer barrel than later weapons. We don’t see much of her face but we are shown her right eye open as she sites her target. Her head is covered in a scarf and she is wearing a white, long-sleeved dress which reaches down to her ankles. Over this she has a purple, sleeveless waistcoat. Around her waist is a belt with a large golden buckle. Over all this there is a long either woollen or sheepskin open jacket, which extends down to her knees. On her feet she has leather shoes with the toe curled upwards. These are a version of the opinga, with the curve upwards at the toe but it was only the men who wore the shoes with the woollen ball attached.

Both these characters stand on a stylised platform representing the hills and mountains of Albania. As in many paintings and lapidars this places the scene firmly in the Albanian context and has been a trope used since the very early days of Albanian Socialist Realism.

The top right of the panel has two males involved in a sword fight. The one on the left has his back to us and is wearing a black xhaqeta (waistcoat) whilst his opponent’s is white – so this could have been the way they delineated the teams – and we see the right side of his face in profile. The other we see his body front on whilst the left side of his face is in profile. There’s no real sense of aggression in this image as the swords, which are crossed at waist height, both point downwards as if parrying an attack. The swordsman on the left has his left hand resting on the top edge of his scabbard, which is worn at his waist and which has a slight curve at the end. This seems to be a bit strange in any contest as a scabbard would only be a hindrance in competition. His opponent, on the other hand, has his left arm extended behind his back (which anyone familiar with present day competition fencing would recognise) aiding in his balance when either attacking or defending. Although it’s not possible to see the end of the swords they look as if they are straight, without any curved ends.

Below the fencers there are two scenes. On the left two males are wrestling against each other, only being able to see the face of the one on the left as the wrestler on the right has his head down, seemingly straining to get an advantage over his opponent.

The other, and last, individual on this panel is of a single male grasping a huge rock to his chest. This is obviously a weightlifting contest, there being an awful lot of rocks in Albania and the only criteria needed in such a competition was to select one that was heavy, no world records being attempted and therefore no strict measurements being needed. This competitor is only the second on this panel to be wearing a fustenella and he is also the only one to be sporting a bushy, black moustache – a sign of his physical age.

Weight Lifter

For reasons I don’t understand some (though not all) of the figures, as well as their instruments, are surrounded by a translucent lilac halo. This seems to have little use as the figures and their sports equipment are clearly delineated from the background, which is a light, reddish-brown throughout, and the fact it is not used all the time is even more of a mystery.

At the top and bottom edge of the panel there are geometric, pyramidal, designs in red, white and black, a pattern which is repeated three times along the length of the mosaic. There are no such designs on either edge, the action scenes going to the end on both sides. The whole mosaic has a red wooden border around the four sides.

It might be pertinent to point out (again) that, apart from the woman with a gun – which is an important statement in its own right – women are not shown as taking part in sporting activities, although there must have been sports or games in which peasant women would have taken part on a regular basis. This just goes to show that it’s a bit of minefield when we wish to represent those things of the past in the present – what you leave out being as important as what is included.

Although the location was a building site (in suspension) when I visited, in the summer of 2016, the mosaic looks in a reasonably good condition, a little dusty, perhaps, but not showing any real signs of damage – either intentional or accidental. I wasn’t able to ascertain what the plans were in completing the renovation of this area but it is hoped that when it is eventually finished and people pass on the way to the basketball games they will be able to appreciate a little of their cultural past (although a local person I spoke to, who had visited the Sports Palace during the period of Socialism, couldn’t remember these mosaics).

I’m not exactly sure of the date of this mosaic but there is a clue (possibly) to the artist as in the very bottom, right hand corner (just below the right foot of the weight lifter) are the letters ‘LNSH’. Who that represents I have yet to discover. If that is the artist it would date the mosaics more towards the late 1980s as it was in the final period of Albanian Socialist Art that attribution, either names or initials, started to appear on the works.

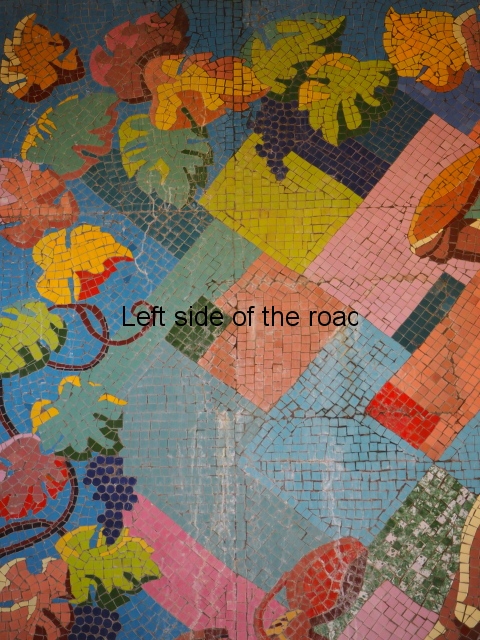

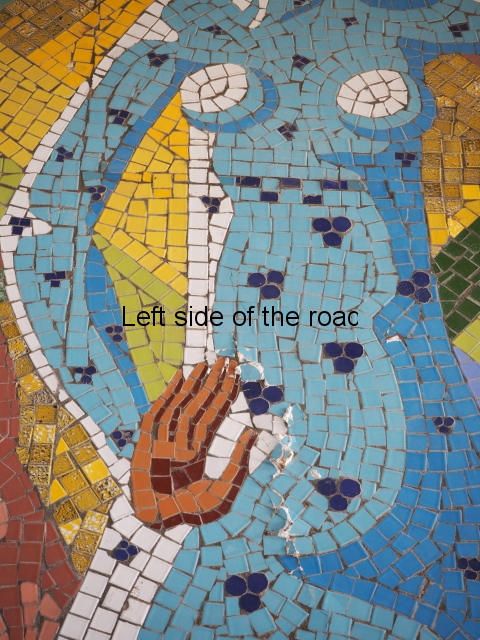

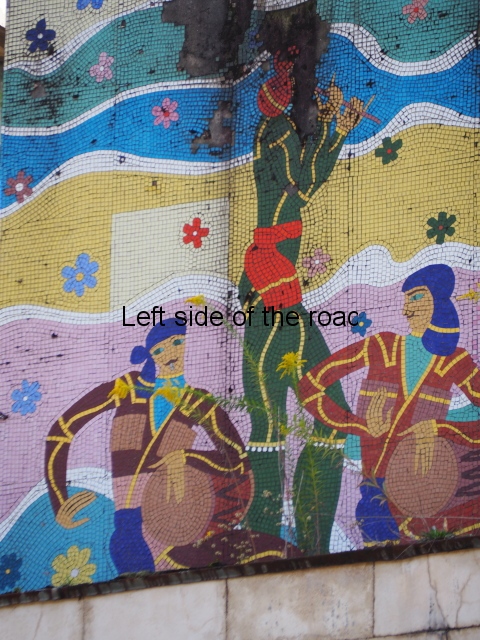

Modern Sport

The panel representing modern sport is of exactly the same size of that depicting traditional sport and can be found on the right hand side of the main entrance hall. (I didn’t measure the panels but a rough estimate would be that they are about 2.5 metres high by 8 metres long.)

This modern panel contains much more movement as well as being more colourful, the athletes wearing clothing appropriate to their sport rather than what was the normal, everyday clothing which is seen in the representation of the traditional sports.

In the top left hand corner there’s a group of seven young women taking part in a medium to long distance run – they’re all bunched up which wouldn’t be the case in a sprint. They are in various colours, both in their shorts and vests. This is a very much more modern representation of women who have come a long way in a short number of years. Pre-liberation the role of women in Albania was very different from what it became under Socialism. After 1944 women were involved in all aspects of society and it should be remembered that there was only one woman depicted in the ‘traditional’ panel so the inclusion of this large group tells the story of how things had changed in a matter of very few years.

Of the seven we see four of the faces in profile, one in semi-profile, one just the hair and one who seems to be looking out at the viewer, smiling. In fact there’s no impression of real effort on the faces of any of the young women. They are running for pleasure not for the victory. This is especially the case of the one in yellow vest who we see in full face. She seems to be saying ‘this is fun, join in’. Whilst all of them have their arms and hands moving in rhythm to their legs she seems to be waving at the viewer, the palm of her hand facing outwards.

The happy runner

And amongst all the colours there’s no sign of the ubiquitous number plate which has become obligatory in individualistic sports, where the winning is all and the participation of those non-competitive are considered a nuisance.

Neither are they running in specialist footwear but simple, light shoes. This has become an industry in its own right, causing all kinds of problems for parents whose children wouldn’t even consider running around a proper track but need this ‘specialist’ footwear just to go to school.

Here we get the representation that sport is something that should be encouraged but not something that becomes the be all and end all. I’ll accept that this was distorted under revisionism where sport was another battlefield in the so-called ‘Cold War’, but that’s not what it should be in a Socialist society.

Following the same pattern as in the previous panel, there is action on two different levels.

Below the female runners we have a couple of males playing football. One of them, on the left, is in a red strip, with a red shirt, shorts and socks, whilst the other is in a blue shirt with white shorts and yellow socks. They compete over a football, both their right feet almost in contact. It’s clearly seen that they are wearing football boots.

To their right is a swimmer just about to leave the starting block in a race. He’s wearing a yellow skull-cap and green swimming trunks and both his arms are thrown back just at the second before he leaps off the block. There’s a bluish-green representation of the water in the pool just where he’s about to jump.

To the right of him is a female netball player, at full stretch as she leaps off the ground attempting a goal, the ball firmly grasped in both hands. She’s wearing a red vest and green shorts.

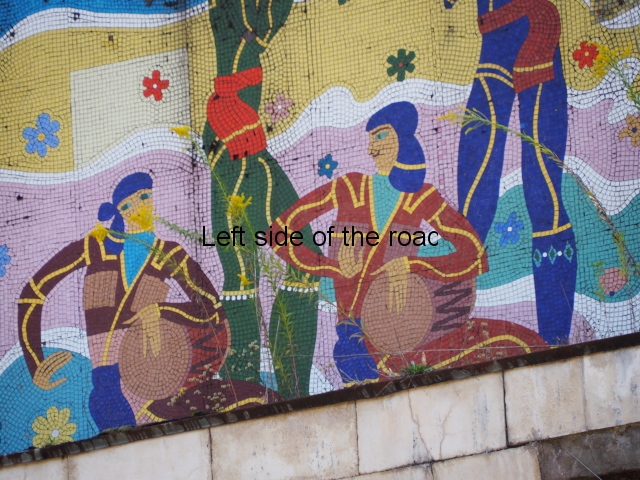

As in the previous mosaic the central figures take up (almost) the whole height of the panel. Here again it is a young man (on the right) and young women (on the left), but in an image that is full of meaning.

The Pickaxe and Rifle

They both face out directly towards the viewer and both are dressed in a red vest and white shorts. They appear as if they are slowing approaching us along a red running track. But these are not ordinary athletes. On her right shoulder a rifle hangs from a strap. We can see the top of the barrel just to the left of her head and the dark, wooden butt peaks out behind her thigh. She grips the strap with her right hand, at chest height.

Her left arm is fully extended and clasps the hand of her male comrade. He is slightly taller than her so is right arm is slightly bent at the elbow. His left arm is also fully extended above his head and he grips a pickaxe handle, at the top of the shaft just before the metal cross-piece. Here, as on the bas reliefs on the exterior of the building, we have the visual expression of the slogan of the Party of Labour of Albania; ‘With a pickaxe in one hand and a rifle in the other, marching forward towards Socialism’. Their clasped hands providing a physical connection between the two parts of the slogan.

Behind their raised arms flutter a group of red flags. The poles of these flags can be seen either side of the male’s head, framed by his upraised arms. These do not carry the symbols of the black double-headed eagle or the gold star of the national flag of the Albanian People’s Republic so these red flags simply represent the Communist movement in general.

Their stance is mirrored in that their right foot is forward and the left close behind, partly hidden. It is here that the first signs of damage, on either of the mosaics, appears. The tiles around the male’s ankle have fallen away and it appears that a somewhat amateurish repair has been made, basically filling the area with plaster. But there is also evidence that this area has had problems in the past as there’s a sizeable area to the right of his feet where the tiles have been replaced but in such a manner that the repair is evident.

Immediately to the right of the two central figures is a male handball player. He mirrors the female netball player on the other side. He is also dressed in a red vest and green shorts, is leaping off the group and is just about to hit the handball with his right hand. The mirror image includes the arching of their backs as they attempt to put as much effort as possible into scoring their goal.

The next image, that takes up the top, right hand corner of the panel contains two parts, one of which is slightly disturbing. The right hand side of this depiction, on the very edge of the panel, is a male and a female, both in the uniform of the People’s Army, including the red stars on their caps, in the act of firing their rifles out of the panel. They have their rifles up to their shoulders and both are kneeling. Behind them, and standing up as she fires, is another female soldier/militia woman firing her rifle. Long, dark brown hair spills out under her cap, which also displays a red star. This little detail says quite a lot as in many parts of the country these small representations of Communism have been vandalised

So far so good. In a Socialist country, constantly being threatened from outside (and by inside renegades and traitors) it’s quite rational that fire arms practice should appear on a panel which is devoted to sport.

Another aspect of defence is that a healthy and fit militia force is much more effective than the sickly individuals that make up so much a proportion of the young population in many capitalist countries in the present day. It’s somewhat ironic that a hundred years after the First World War (where so many conscripts were basically unfit to fight) the health levels of the young people in a country like Britain are at as bad a level as they were following the century of capitalism using, or more accurately abusing, people’s bodies for profit. A hundred years ago it was by exploiting young people in the factories, mills and mines of Britain, now it’s in feeding them cheap, fatty, over-sugered so-called ‘fast’ and convenience foods – and blaming them for their condition.

Being hit by a rifle butt

The disturbing portion of this image is to the left of the rifleman and women. Here we have a militia man hitting, seemingly at full force, another militia man in the face with the butt of his rifle. The militia man doing the hitting wears a cap with a red star (and it’s also possible to see the bayonet fixed, if you look closely enough) but the reaction of the man being hit is real, this is not play acting. I can accept that hand to hand combat is part of military training but this seems to be an extreme manner in which to represent this sort of training. Your aim is to kill or disable the enemy, not your own side.

Finally, in the bottom right hand corner, matters return to the ideal of sport rather than training.

In the same location as in the panel on traditional sport there are two men wrestling. Now no longer encumbered by clothing and constraints of the culture of yore they are shown more akin to the wrestlers of classical times. They wear shorts, one is in red, one in blue, and they are head to head in an exact sense as we only see the tops of their heads, the muscles of their bodies straining to get the better of the other.

The last figure is that of a young female gymnast. She is dressed in a pink leotard and is in the act of performing a routine with a ring. Her left hand is outstretched above her head, her right hand grips the ring whilst her left leg is bent high as she stands on tiptoe with her right – all elements giving the impression of movement and grace.

This panel is the same as the first in that the top and bottom of the action is decorated with similar geometric designs and the whole thing is encased in a red, wooden frame.

As I started to look in a detailed manner at the two mosaics I started to think that the images were so different that more than one artist was involved. Then I realised that the same letters, NLSH, can just be made out on the very bottom frieze, between the feet of the footballer on the extreme left, in an area where there has been some slight damage. This made me think that it’s possible the letters don’t refer to an individual but to a collective, the letters SH being the abbreviation of Shqipëri (Albania). So the letters could stand for an artistic grouping – but that’s just speculation

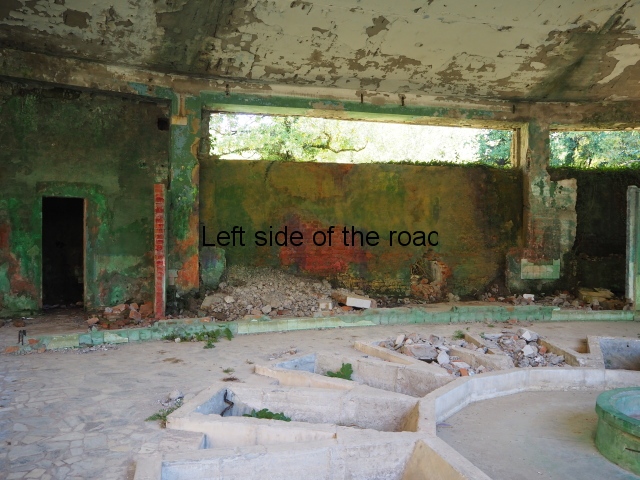

Access to the mosaics isn’t easy. I was able to convince someone in the office (accessed from the entrance at the back of the building) to allow me to see the traditional panel. We went across the basket ball court and then through a temporary barrier to come to an area that is part building site, rubble and debris strewn around.

There is, however, a substantial barrier between the two mosaics at present. Originally all the glass doors at the front of the building would have gained entrance to a common foyer. The stairs up to the main sports hall are located between the two mosaics and the foyer would have served as such places do throughout the world, as a meeting place either before or after the performance.

With the most recent ‘renovation’ this common area has been broken up and a substantial dividing wall now exists between the mosaics. I had to go back early the following morning to meet up with the key holder of the right hand section as this is now the location of the local weightlifting (peshëngritje) club, the mats and weights in the area in front of the Socialist work of art. They could use the image of the weight lifter in the traditional panel as a logo, to give their club a distinctive image but I doubt if anyone has ever thought of that.

Location

The erstwhile Palace of Sport is found set back from the road at the bottom end of Rruga Sadiki Zotaj at Sheshi Pavarësia (Independence Square). This is close to the roundabout that takes you right to the docks and ferry port and straight on to the hotels and beaches (coming from Fier).

GPS

N 40.454991

E 19.487818

DMS

40°27’18.0″N

19°29’16.1″E

More on Albania …..