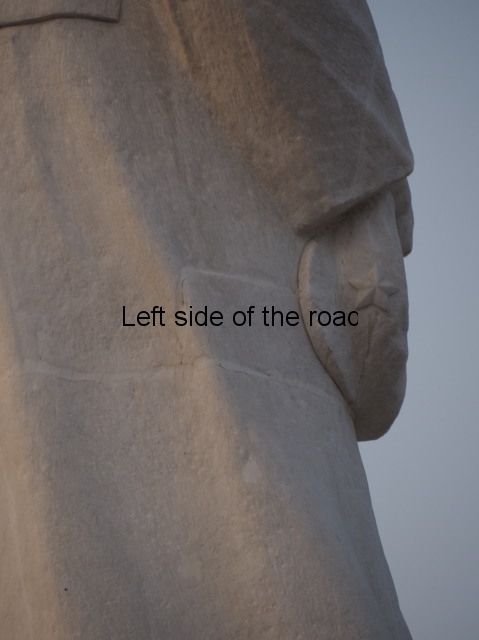

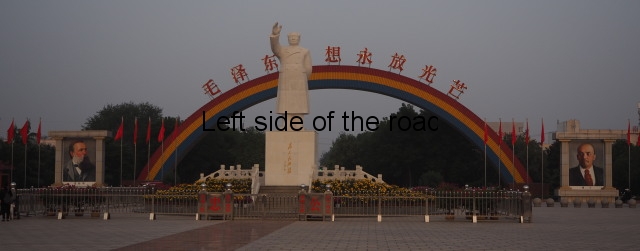

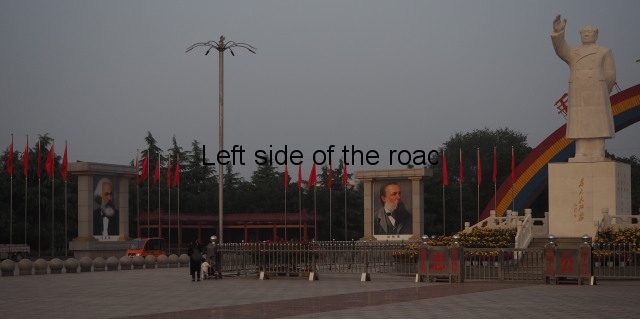

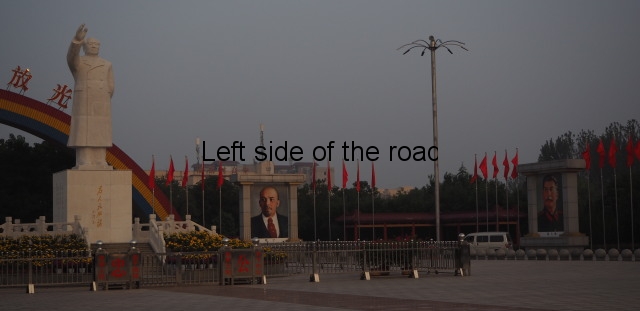

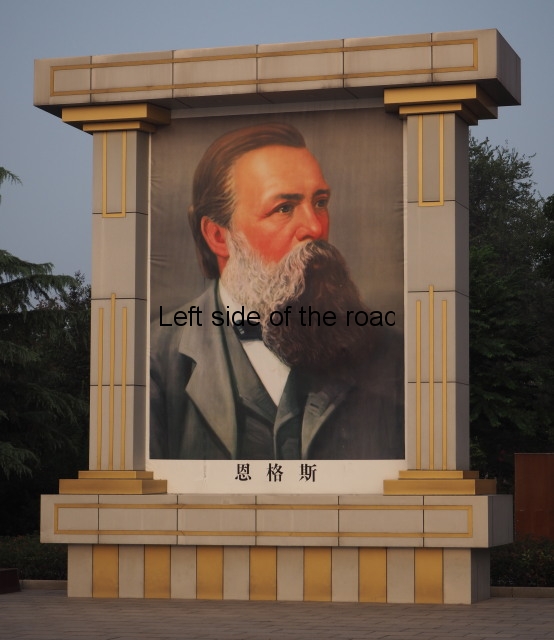

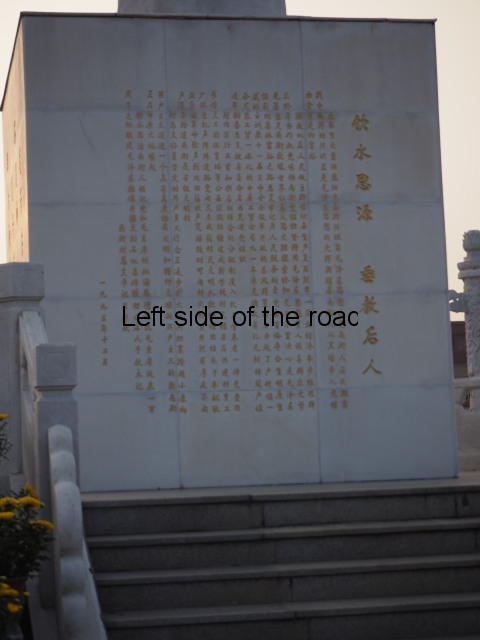

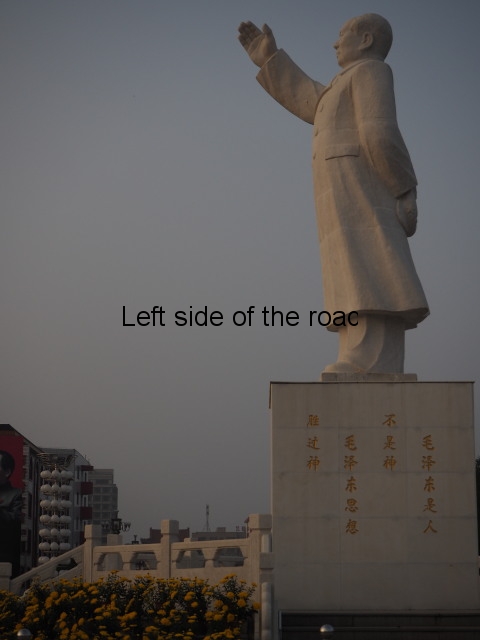

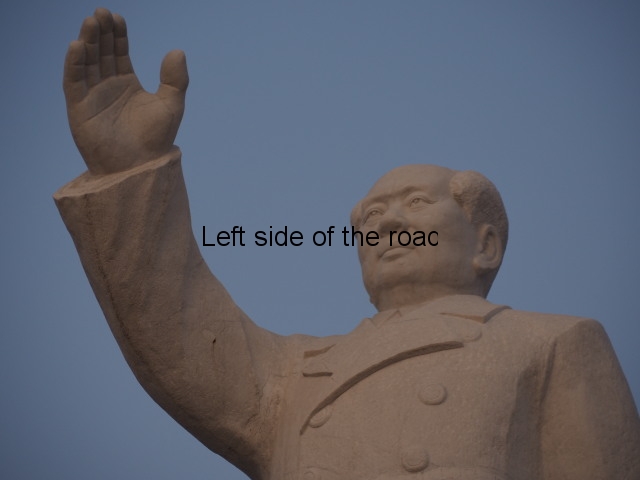

GPCR in Sining, Chinghai Province

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China

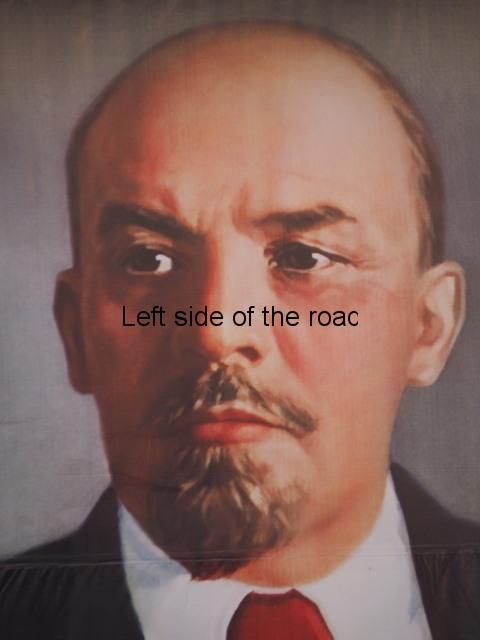

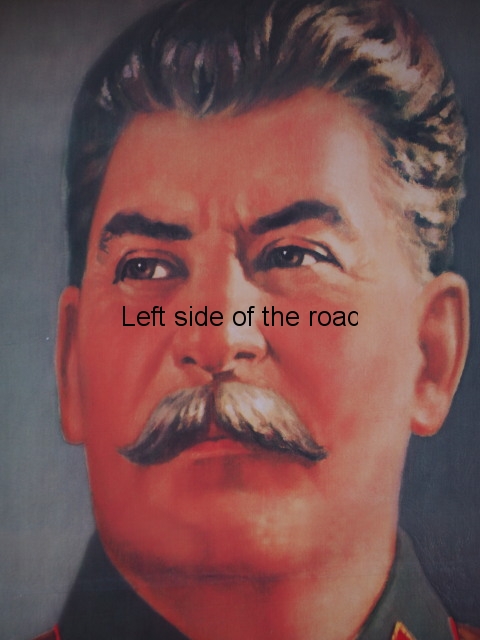

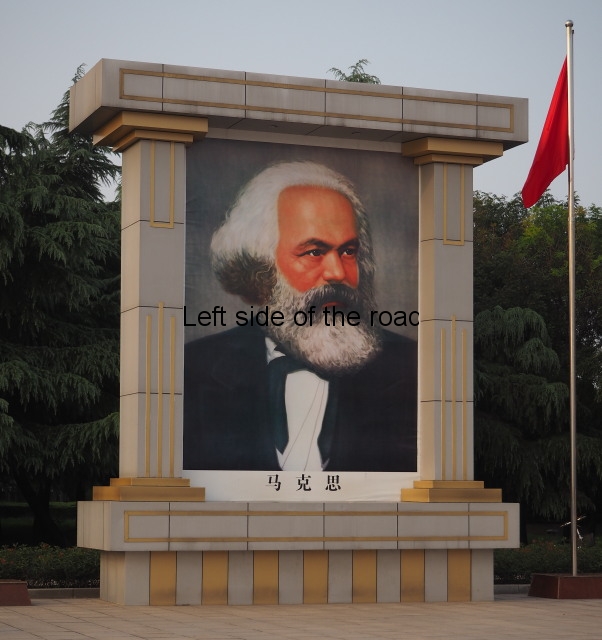

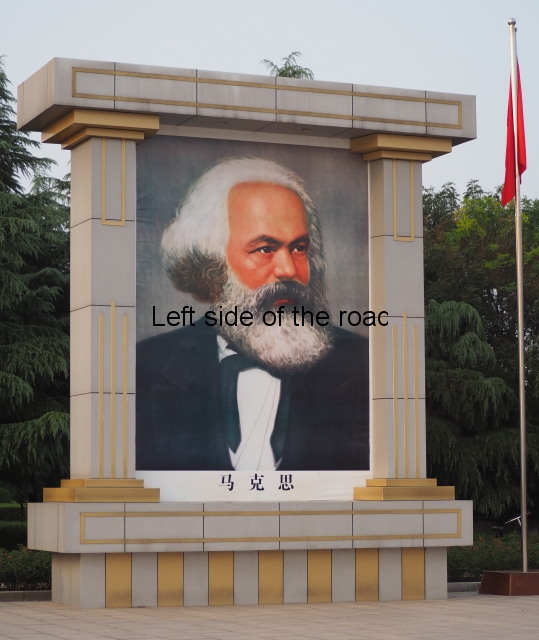

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China was the logical outcome of the many years of the increasingly bitter ideological struggle that had been taking place within the International Communist Movement since Khrushchev’s denunciation of Joseph Stalin at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in February 1956.

There had been many efforts (some would say too many) to try and bring the errant first Socialist State back to the revolutionary principles of Marxism-Leninism but by 1960 it was becoming obvious that the revisionists had become firmly entrenched in Lenin‘s and Stalin‘s Party. Weaknesses (and the similar entrenchment of revisionism and social democracy) in other Communist and Workers’ Parties worldwide also ensured that those seeking to restore capitalism – in deeds if not in words – in the Soviet Union could claim they were only reflecting the majority trend in the International Communist Movement.

Although the majority of the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party was still following the revolutionary road those ‘capitalist-roaders’ (as they were called in China) did exist – and even at the highest levels in the Party.

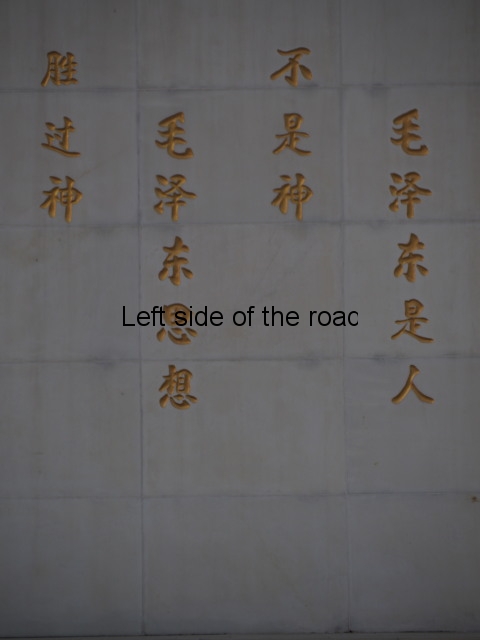

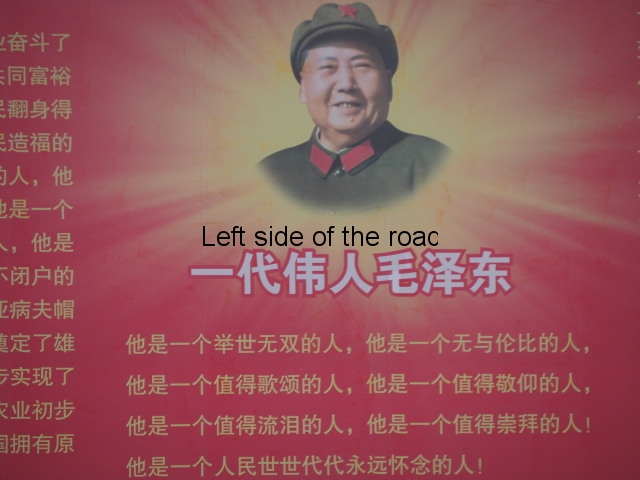

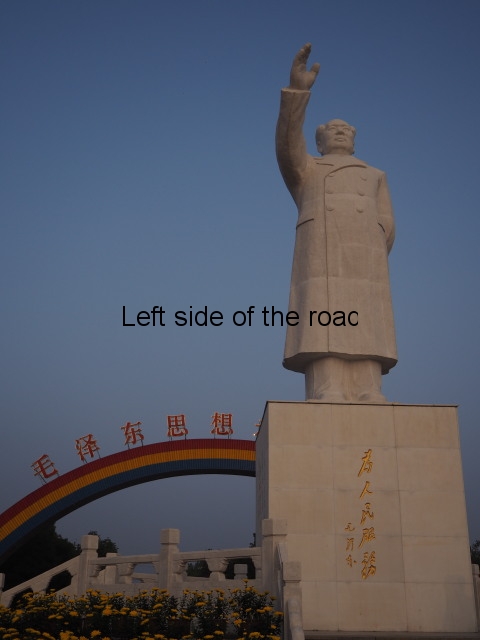

Those revolutionaries, under the leadership of Chairman Mao Tse-tung, had to act to prevent China from going down the same anti-Socialist road. It would be for the Chinese workers, peasants, soldiers and students to decide the fate of their country. So, on 8th August 1966, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was born – one of the most important and significant events in the history of Communism.

Basic Documents of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

Decision of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party Concerning the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, adopted on Aug. 8, 1966, 20 pages. [This famous Circular of the Central Committee of the CCP was drawn up under Mao’s guidance and presents the 16 key points established to guide the GPCR.]

An Epoch-Making Document – In Commemoration of the Second Anniversary of the Publication of the Circular, May 17, 1968, 28 pages.

The Great Socialist [Proletarian] Cultural Revolution Series (1966-1967):

The Great Socialist Cultural Revolution in China (1), 2nd ed. (Peking: FLP, Oct. 1966), 78 pages. Includes these articles:

- Hold High the Great Red Banner of Mao Tse-tung’s Thought and Actively Participate in the Great Socialist Cultural Revolution, editorial of the Liberation Army Daily [Jiefangjun Bao], April 18, 1966.

- Never Forget the Class Struggle, editorial of the Liberation Army Daily, May 4 1966.

- On ‘Three-Family Village’ — The Reactionary Nature of Evening Chats at Yenshan and Notes from Three-Family Village, by Yao Wen-yuan, May 10, 1966.

The Great Socialist Cultural Revolution in China (2), (Peking: FLP, 1966), 68 pages. Includes these articles:

- Open Fire at the Black Anti-Party and Anti-Socialist Line!, by Kao Chu, first published in the Liberation Army Daily, May 8, 1966.

- Heighten Our Vigilance and Distinguish the True from the False, by Ho Ming, first published in the Kuangming Daily, May 8, 1966.

- Teng To’s Evening Chats at Yenshan is Anti-Party and Anti-Socialist Double-Talk, compiled by Lin Chieh, Ma Tse-min, Yen Chang-huei, Chou Ying, Teng Wen-sheng and Chin Tien-Liang, first published in the Liberation Army Daily and the Kuangming Daily on May 8, 1966.

- On the Bourgeois Stand of Frontline and the Peking Daily, by Chi Pen-yu, first published in Red Flag, No. 7, 1966.

The Great Socialist Cultural Revolution in China (3), (Peking: FLP, 1966), 32 pages. Includes these articles:

- Sweep Away All Monsters, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], June 1, 1966.

- A Great Revolution That Touches People to Their Very Souls, editorial of Renmin Ribao, June 2, 1966.

- Mao Tse-tung’s Thought is the Telescope and Microscope of Our Revolutionary Cause, editorial of Jiefangjun Bao [Liberation Army Daily], June 7, 1966.

- We are Critics of the Old World, editorial of Renmin Ribao, June 8, 1966.

The Great Socialist Cultural Revolution in China (4), (Peking: FLP, 1966), 56 pages, Includes these articles:

- Long Live the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, editorial of Hongqi [Red Flag], No. 8, 1966.

- Capture the Positions in the Field of Historical Studies Seized by the Bourgeoisie, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], June 3, 1966.

- Tear Aside the Bourgeois Mask of ‘Liberty, Equality and Fraternity’, editorial of Renmin Ribao, June 4, 1966.

- New Victory for Mao Tse-tung’s Thought, editorial of Renmin Ribao, June 4, 1966.

- To Be Proletarian Revolutionaries or Bourgeois Royalists?, editorial of Renmin Ribao, June 5, 1966.

The Great Socialist Cultural Revolution in China (5), (Peking: FLP, 1966), 36 pages, pamphlet with just one article:

- Raise High the Great Red Banner of Mao Tse-tung’s Thought and Carry the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution Through to the End — Essential Points for Propaganda and Education in Connection with the Great Cultural Revolution, editorial of Jiefangjun Bao [Liberation Army Daily], June 6, 1966.

The Great Socialist Cultural Revolution in China (6), (Peking: FLP, 1966), 32 pages. Includes these articles:

- A New Stage of the Socialist Revolution in China, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], July 17, 1966.

- The Sunlight of the Party Illuminates the Road of the Great Cultural Revolution, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], June 24, 1966.

- Trust the Masses, Rely on the Masses, editorial of Hongqi [Red Flag], No. 9, 1966.

- From the Masses, to the Masses, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], July 21, 1966.

- Be a Pupil of the Masses Before You Become a Teacher of the Masses, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], July 29, 1966.

The Great Socialist Cultural Revolution in China (7), (Peking: FLP, 1967), 36 pages. Includes these articles:

- The Programmatic Document of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, editorial of Hongqi [Red Flag], No. 10, 1966.

- Master the Ideological Weapon of the Great Cultural Revolution, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], Aug. 11, 1966.

- Study the 16-Point Decision, Know it Well and Apply It, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], Aug. 13, 1966.

- Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], Aug. 15, 1966.

- Revolutionary Youth Should Learn from the People’s Liberation Army, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], Aug. 28, 1966.

- Hold Fast to the Main Orientation in the Struggle, editorial of Hongqi [Red Flag], No. 12, 1966.

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China (8), (Peking: FLP, 1967), 28 pages. Includes these articles:

- Comrade Lin Piao’s Speech at the Peking Mass Rally to Receive Revolutionary Teachers and Students From All Over China, Nov. 3, 1966.

- Victory for the Proletarian Revolutionary Line Represented by Chairman Mao, editorial in Hongqi, No. 14, 1966.

- Seize New Victories, editorial in Hongqi, No. 15, 1966.

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China (9), (Peking: FLP, 1967), 28 pages, pamphlet with just one article:

- Carry the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution Through to the End, editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily] and Hongqi [Red Flag], Jan. 1, 1967.

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China (10), (Peking: FLP, 1967), 48 pages. Includes these articles:

- Message of Greetings to Revolutionary Rebel Organizations in Shanghai from the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, the State Council, the Military Commission of the Party’s Central Committee and the Cultural Revolution Group Under the Party’s Central Committee, Jan. 11, 1967.

- Take Firm Hold of the Revolution, Promote Production and Utterly Smash the New Counterattack Launched by the Bourgeois Reactionary Line – Message to All Shanghai People, Jan. 4, 1967. Urgent Notice – From the Shanghai Workers’ Revolutionary Rebel General Headquarters and 31 Other Revolutionary Mass Organizations, Jan. 9, 1967.

- Telegram Saluting Chairman Mao – From the Rally Held by the Revolutionary Rebel Organizations of Shanghai and the Shanghai Liaison Centres of Revolutionary Rebel Organizations of Other Places to Celebrate the Message of Greetings of the Central Authorities and Completely Smash the New Counter-Attack by the Bourgeois Reactionary Line, from a rally held by revolutionary organizations in Shanghai, Jan. 12, 1967.

- Oppose Economist and Smash the Latest Counterattack by the Bourgeois Reactionary Line – Editorial of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily] and Hongqi [Red Flag], January 12, 1967.

- Proletarian Revolutionaries, Unite, by Commentator, Hongqi, No. 2, 1967.

Other

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution Pamphlets:

1966:

Mao Tse-tung’s Thought is the Invincible Weapon, four articles from 1966, 87 pages. (Peking: FLP, 1968)

1967:

The May Upheaval in Hongkong, by the Committee of Hongkong-Kowloon Chinese Compatriots of All Circles for the Struggle Against Persecution by the British Authorities in Hongkong, (Hongkong: 1967), 191 pages. About the extension of the Cultural Revolution to Hongkong.

Follow Chairman Mao and Advance in the Teeth of Great Storms and Waves, article about Mao’s famous swim in the Yangtse along with editorials from Renmin Ribao and Jiefangjun Bao, July 24-26, 1966, 28 pages. (Peking: FLP, 1967)

Forward Along the High Road of Mao Tse-tung’s Thought — In Celebration of the 17th Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China, including editorials and speeches by Lin Piao and Chou En-lai on Oct. 1, 1966, 42 pages. (Peking: FLP, 1967) PDF format [2,031 KB].

Betrayal of Proletarian Dictatorship is the Heart of the Book on ‘Self-Cultivation’, by the editorial departments of Renmin Ribao and Hongqi, May 8, 1967, 24 pages. (Peking: FLP, 1967)

Patriotism or National Betrayal? – On the Reactionary Film Inside Story of the Ching Court, by Chi Pen-yu, 44 pages. Original Chinese version in Hongqi #5, 1967. (Peking: FLP, 1967)

Great Victory for Chairman Mao’s Revolutionary Line – Warmly Hail the Birth of Peking Municipal Revolutionary Committee, including speeches by Chou En-lai, Chiang Ching, Hsieh Fu-chih, Chang Chun-chiao and editorials from Renmin Ribao and Jifangjun Bao, (Peking: FLP, 1967), 60 pages.

Commemorating Lu Hsun – Our Forerunner in the Cultural Revolution, a collection of speeches and articles on the 30th anniversary of the death of Lu Hsun, including speeches by Chen Po-ta, Yao Wen-yuan, Kuo Mo-jo and others, (Peking: FLP, 1967), 68 pages.

The Struggle Between the Two Roads in China’s Countryside, by the editorial departments of Renmin Ribao, Hongqi and Jifangjun Bao, Nov. 23, 1967, 36 pages. (Peking: FLP, 1968)

1968:

Take the Road of the Shanghai Machine Tools Plant in Training Technicians from among the Workers – Two Investigation Reports on the Revolution in Education in Colleges of Science and Engineering, by the editorial departments of Renmin Ribao and Hongqi, 68 pages. (Peking: FLP, 1968)

On the Revolutionary ‘Three-in-One’ Combination, four editorials by Hongqi, Jiefangjun Bao, or Wenhui Bao in the first half of 1967, 48 pages. (Peking: FLP, 1968)

On the Re-Education of Intellectuals, by Renmin Ribao and Hongqi Commentators, originally in Hongqi, #3, 1968. (Peking: FLP, 1968), 20 pages.

Absorb Proletarian Fresh Blood – An Important Question in Party Consolidation, Hongqi [Red Flag] editorial, #4, Oct. 14, 1968. (Peking: FLP, 1968), 34 pages.

1969:

Put Mao Tse-tung’s Thought in Command of Everything, New Year editorial for 1969 by Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily], Hongqi [Red Flag] and Jiefangjun Bao [Liberation Army Daily]. (Peking: FLP, 1969), 39 pages.

Grasp Revolution, Promote Production and Win New Victories on the Industrial Front, Renmin Ribao editorial, Feb. 21, 1969. (Peking: FLP, 1969), 26 pages.

Carry the Great Revolution on the Journalistic Front Through to the End — Repudiating the Counter-Revolutionary Revisionist Line on Journalism of China’s Khrushchov, by the editorial departments of Renmin Ribao, Hongqi and Jifangjun Bao. (Peking: FLP, 1969), 74 pages.

Hold Aloft the Banner of Unity of the Party’s Ninth Congress and Win Still Greater Victories, editorial of Renmin Ribao, Hongqi and Jifangjun Bao, June 9, 1969. (Peking: FLP, 1969), 26 pages.

Fight for the Further Consolidation of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat – In Celebration of the 20th Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China. Includes speeches by Lin Piao and Chou En-lai, an editorial, and slogans for the celebration. (Peking: FLP, 1969), 54 pages.

1970:

Usher In the Great 1970’s, 1970 New Year’s Day editorial of Renmin Ribao, Hongqi and Jiefangjun Bao. (Peking: FLP, 1970), 34 pages.

Take the Road of Integrating with the Workers, Peasants and Soldiers, on the orientation of the youth movement. (Peking: FLP, 1970), 105 pages.

Communists Should Be the Advanced Elements of the Proletariat – In Commemoration of the 49th Anniversary of the Founding of the Communist Party of China. (Peking: FLP, 1970), 20 pages.

1971:

Outstanding Proletarian Fighters, about outstanding proletarian revolutionaries arising in all walks of life in China. (Peking: FLP, 1971), 101 pages.

To Trumpet Bourgeois Literature and Art is to Restore Capitalism – A Repudiation of Chou Yang’s Reactionary Fallacy Adulating the ‘Renaissance’, the ‘Enlightenment’ and ‘Critical Realism’ of the Bourgeoisie, by the Shanghai Writing Group for Revolutionary Mass Criticism, (Peking: FLP, 1971), 53 pages.

1972:

Strive to Build a Socialist University of Science and Engineering, about the Cultural Revolution in education. (Peking: FLP, 1972), 85 pages. In addition to the title article by the Workers’ and PLA Men’s Mao Tsetung Thought Propaganda Team at Tsinghua University, this pamphlet also includes the Summary of the Forum on the Revolution in Education in Shanghai Colleges of Science and Engineering convened by Chang Chun-chiao an Yao Wen-yuan in Shanghai, June 2, 1970.

Strive for New Victories, in Celebration of the 23rd Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China, editorial by Renmin Ribao, Hongqi and Jiefangjun Bao, (Peking: FLP, 1972), 18 pages.

1974:

A Vicious Motive, Despicable Tricks – A Criticism of M. Antonioni’s Anti-China Film China, by Renmin Ribao Commentator, Jan. 30, 1974. (Peking: FLP, 1974), 23 pages.

1976:

A Summary of the Opinions of the Inner-Party Bourgeoisie Issues, a Guangzhou area regional CCP document which was reprinted by the Publicity Department of Zhongshan County Committee of the CCP, and which is based on theoretical seminar materials and also the relevant articles of some university journals. It is only to promote further discussion and study by comrades on the inner-party bourgeoisie issue. (July 8, 1976), 14 pages. This document is especially interesting in that it is in part a late period summary of the central aspects of the entire GPCR. It consists of the following six sections:

- Chairman Mao’s scientific assertion that the bourgeoisie emerged within the Communist Party is a major development of Marxism-Leninism

- On how to understand the problem that the bourgeoisie is just in the Communist Party

- On the question of changes in class relations during the socialist period

- On the root causes of the bourgeoisie within the party

- About the characteristics of the bourgeoisie within the party and the contradictory nature of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie within the party

- Recognition and struggle against the bourgeoisie in the party

(An English translation should be available soon.)

Collections of Documents from the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution:

Important Documents on the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China, which consists mostly of speeches by Lin Piao [Lin Biao]. Pocket edition with red plastic cover. (Peking: FLP, 1970), 350 pages.

Fundamentals of Political Economy, edited and with an introduction by George C Wang, ME Sharpe, New York, 1977, 506 pages. This was an introductory economics text produced in 1974 as part of a Youth Self-education series for individual or group study – primarily designed to raise the cultural level of the young people who were going to the countryside.

And Mao Makes 5: Mao Tse-tung’s last great battle, edited with an Introduction by Raymond Lotta, (Chicago: Banner Press, September 1978), 539 pages.

Contents:

Introduction:

Section I: Background to the Struggle:

- Text 1: Report at the Central Study Class, by Wang Hung-wen

- Text 2: The Laws of Class Struggle in the Socialist Period, by Chi Ping

- Text 3: Report to the Tenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China, delivered by Chou En-lai

- Text 4: Report on the Revision of the Party Constitution, by Wang Hung-wen

Section II: Criticize Lin Piao and Confucius:

- Section II Intro:

- Text 5: Carry the Struggle to Criticize Lin Piao and Confucius Through to the End

- Text 6: Dare to Think and Do

- Text 7: Study the Historical Experience of the Struggle Between the Confucian and Legalist Schools, by Liang Hsiao

- Text 8: The Philosophy of the Communist Party is the Philosophy of Struggle, by Chiang Yu-ping

- Text 9: Working Women’s Struggle Against Confucianism in Chinese History

- Text 10: To Develop Industry We Must Initiate Technical Innovation, by Kung Hsiao-wen

- Text 11: Has Absolute Music No Class Character?, by Chao Hua

- Text 12: A Decade of Revolution in Peking Opera, by Chu Lan

- Text 13: History Develops in Spirals, by Hung Yu

- Text 14: Speech at Peking Rally Welcoming Cambodian Guests, by Wang Hung-wen

Section III: Fourth People’s Congress and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat Campaign:

- Section III Intro:

- Text 15: Report on the Work of the Government, delivered by Chou En-lai

- Text 16: Report on the Revision of the Constitution, delivered by Chang Chun-chiao

- Text 17: Study Well the Theory of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat

- Text 18: On the Social Basis of the Lin Piao Anti-Party Clique, by Yao Wen-yuan

- Text 19: On Exercising All-Round Dictatorship Over the Bourgeoisie, by Chang Chun-chiao

- Text 20: Fighting With the Pen and Steel Rod

- Text 21: Socialist Big Fair Is Good

Section IV: Criticize Water Margin:

- Section IV Intro:

- Text 22: Unfold Criticism of ‘Water Margin’

- Text 23: Criticism of ‘Water Margin’, by Chu Fang-ming

- Text 24: On Teng Hsiao-ping’s Counter-Revolutionary Offensive in Public Opinion (Excerpts), by Hung Hsuan

Section V: Criticize Teng and Beat Back the Right Deviationist Wind:

- Section V Intro:

- Text 25: Two Poems, by Mao Tse-tung

- Text 26: Reversing Correct Verdicts Goes Against the Will of the People

- Text 27: Counter-Revolutionary Political Incident at Tien An Men Square

- Text 28: Communist Party of China Resolutions

- Text 29: Firmly Keep to the General Orientation of the Struggle

- Text 30: A General Program for Capitalist Restoration, by Cheng Yueh

- Text 31: Criticism of Selected Passages of ‘Certain Questions on Accelerating the Development of Industry’

- Text 32: Comments on Teng Hsiao-ping’s Economic Ideas of the Comprador Bourgeoisie, by Kao Lu and Chang Ko

- Text 33: A New Type of Production Relations in a Socialist Enterprise

- Text 34: Fundamental Differences Between the Two Lines in Education

- Text 35: Repulsing the Right Deviationist Wind in the Scientific and Technological Circles

- Text 36: What Is the Intention of People of the Lin Piao Type in Advocating ‘Private Ownership of Knowledge’?, by Liang Hsiao

- Text 37: A Reactionary Philosophy That Stands on Its Head, by Hung Yu

- Text 38: From Bourgeois Democrats to Capitalist-Roaders, by Chih Heng

- Text 39: Capitalist-Roaders Are the Bourgeoisie Inside the Party, by Fang Kang

- Text 40: Capitalist-Roaders Are Representatives of the Capitalist Relations of Production, by Chuang Lan

- Text 41: Talks Concerning ‘Criticizing Teng Hsiao-ping and Repulsing Right Deviationist Wind’, by Chang Chun-chiao

- Text 42: Deepen the Criticism of Teng Hsiao-ping in Anti-Quake and Relief Work

- Text 43: Proletarians Are Revolutionary Optimists, by Pi Sheng

Biographical Material on the Four: 13 pages of photographs

Appendices: Documents from the Right:

- Introduction:

- Appendix 1: On the General Program of Work for the Whole Party and Whole Nation

- Appendix 2: Some Problems in Accelerating Industrial Development

- Appendix 3: On Some Problems in the Fields of Science and Technology

- Appendix 4: Two Talks by Teng Hsiao-ping

- Appendix 5: The Bitter Fruit of Maoism, by Y. Semyonov

- Appendix 6: Speech at Special Session of UN General Assembly, by Teng Hsiao-ping

- Appendix 7: A Complete Reversal of the Relations Between Ourselves and the Enemy, by Hsiang Chun

- Appendix 8: CPC Central Committee Circular on Holding National Science Conference

- Appendix 9: To Each According to His Work: Socialist Principle in Distribution, by Li Hung-lin

CCP Documents of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution: 1966-67, (Hong Kong: Union Research Institute), 1967 [?], 361 pages. This work included the original Chinese language documents plus the English translations. This version, however, only includes the English translations.

Commentaries on the GPCR

The papers included here might well be anti-GPCR but they contain either documents or information which will help to get a greater understanding of this crucial political movement.

Chinese Communism in crisis – Maoism and the Cultural Revolution, Jack Gray and Patrick Cavendish, Frederick A Praeger, New York, 1968, 279 pages.

The Cultural Revolution in China, Joan Robinson, Penguin, London, 1970, 154 pages.

Hundred Day War, the Cultural Revolution at Tsinghua University, William Hinton, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1972, 288 pages.

Micropolitics in Contemporary China – A Technical Unit during and after the Cultural Revolution, Marc J Blecher and Gordon White, ME Sharpe, New York, 1979, 135 pages.

Evaluating the Cultural Revolution in China and its legacy for the future, MLM Revolutionary Study Group in the US, 2007, 86 pages.

Reflections on my trip to China in 1971 and the eventual victory of the ‘Capitalist Roaders’, Barry York, C21st Left, 2020, 9 pages.