Moscow Metro – a Socialist Realist Art Gallery

Moscow Metro – Taganskaya – Line 5

Taganskaya (Russian: Тага́нская) is a station on the Koltsevaya line of the Moscow Metro. It opened on 1 January 1950 with the first segment of the fourth stage of the system. The station is named after the Taganka Square which is a major junction of the Sadovoye Koltso.

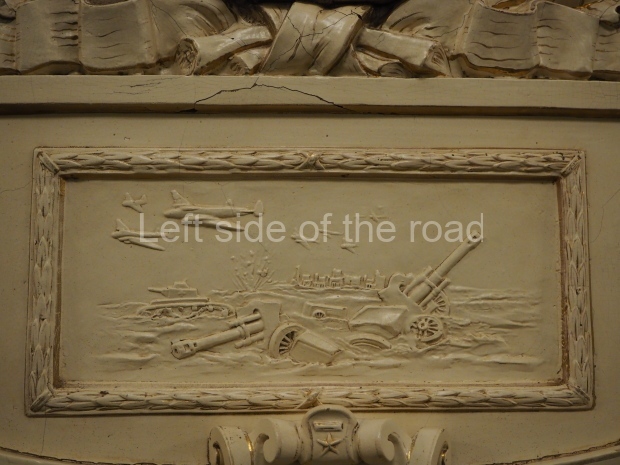

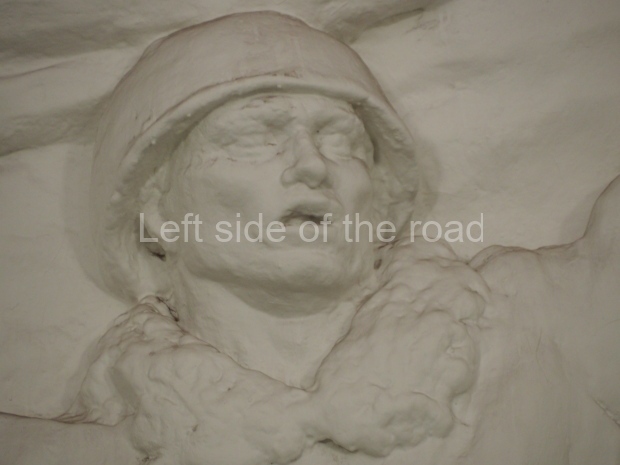

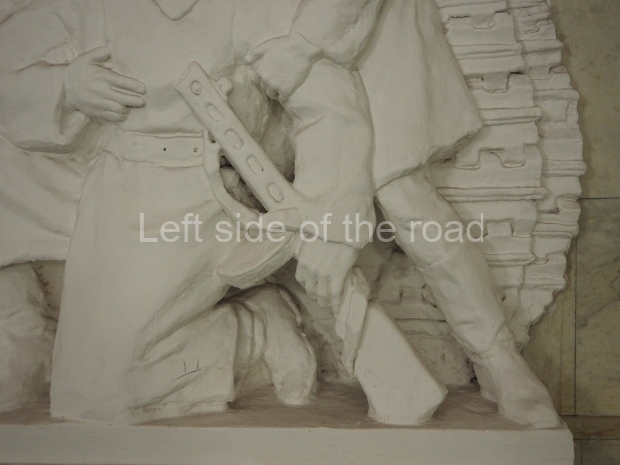

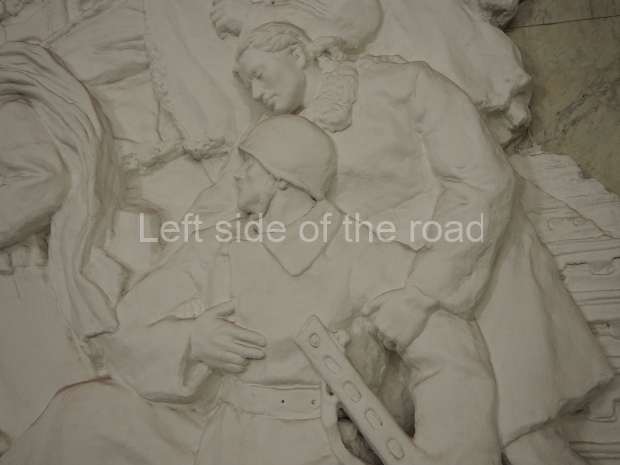

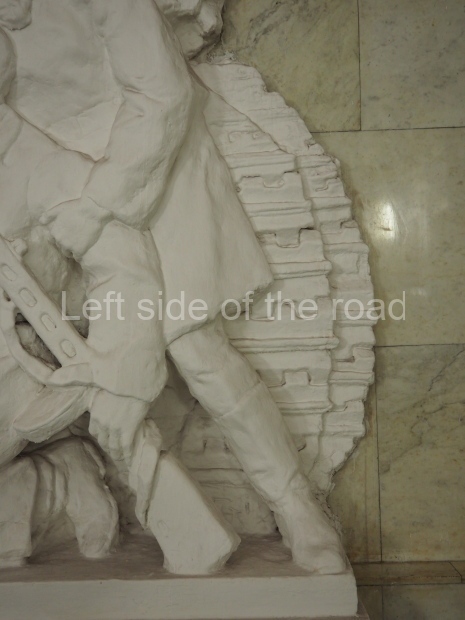

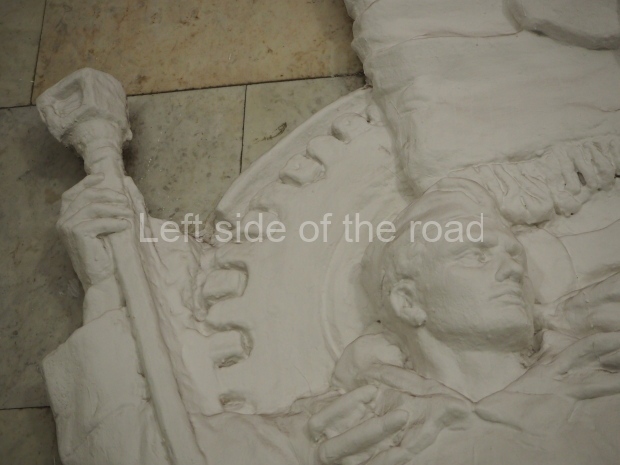

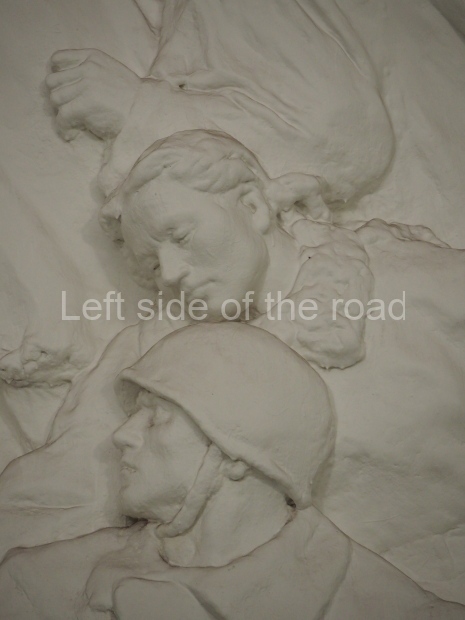

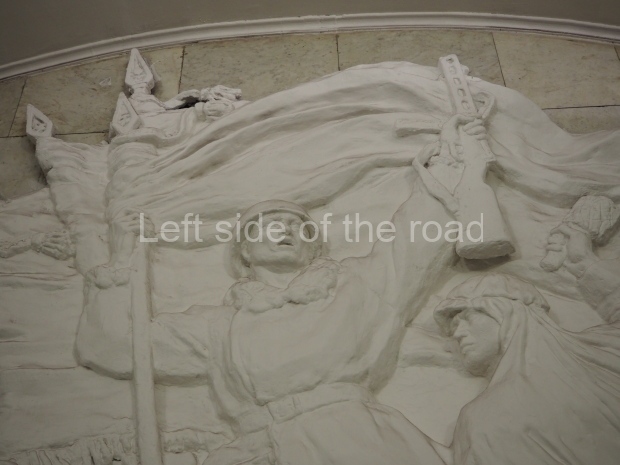

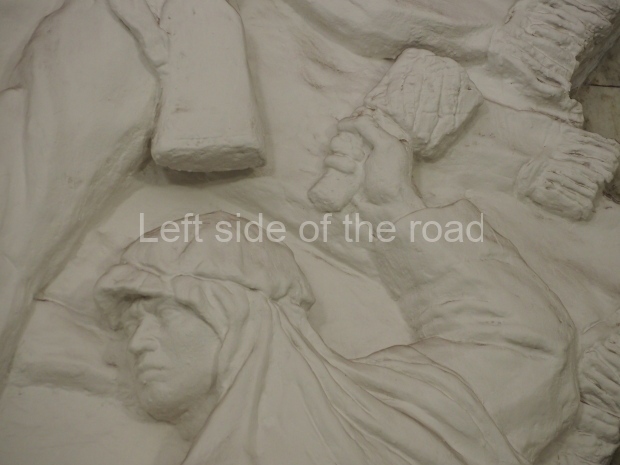

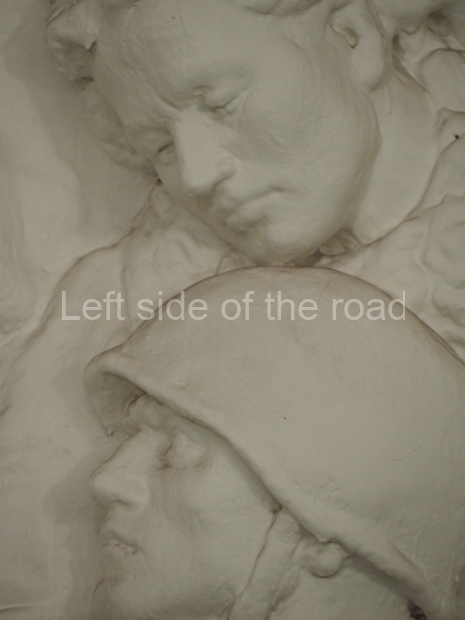

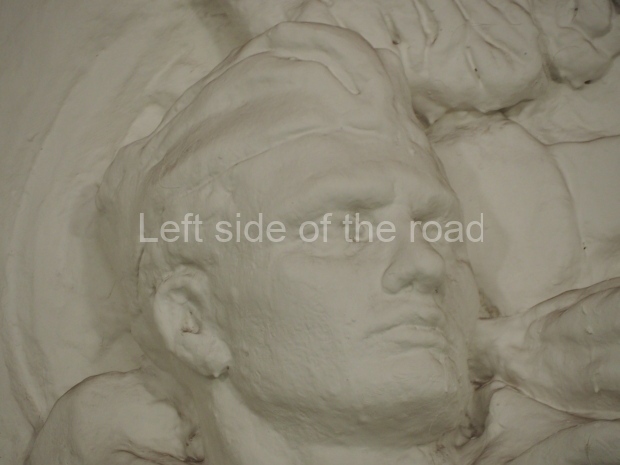

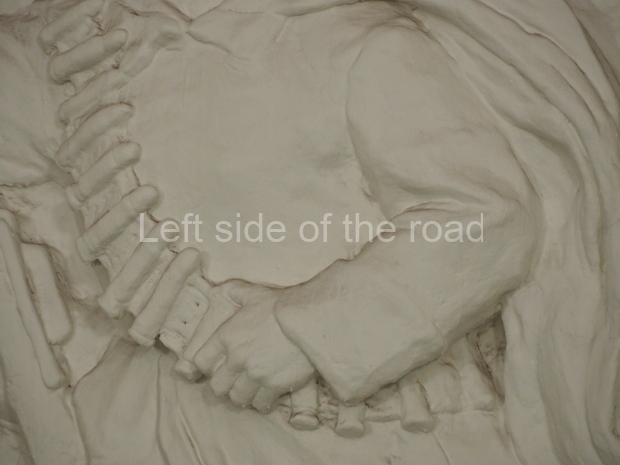

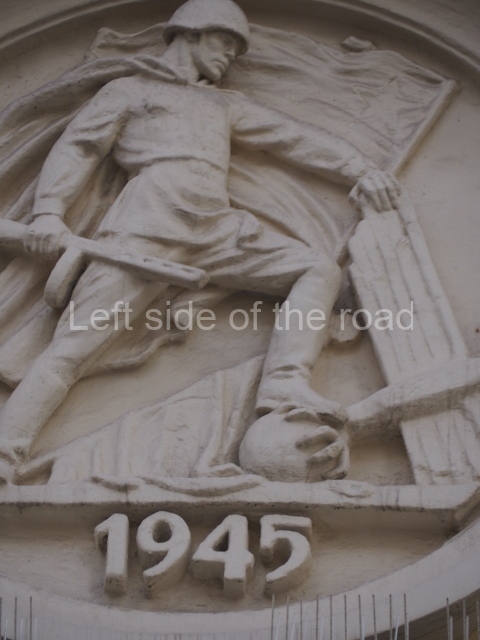

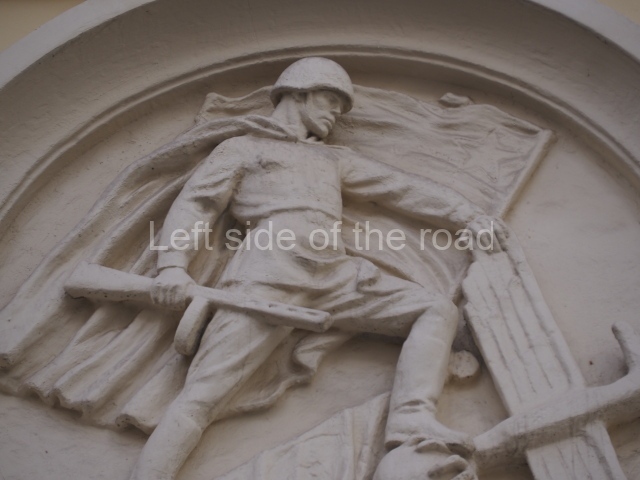

Designed by architects K. Ryzhkov and A. Medvedev, this pylon station was built with the post-war flamboyance in mind, the overall design is based on the traditional Russian motives in decorations. The central feature of the station are 48 majolica [earthenware] panels located on each face of the pylon. (The work of Ye. Blinova, P. Kozhin, A. Sotnikov, A. Berzhitskaya and Z. Sokolova). These contain apart from floral elements, profile bas-reliefs of various World War II Red Army and Navy servicemen each dedicated to a group such as pilots, tank crews, sailors etc. The colour gamma is balanced in such a way that the panels facing the central hall are on a blue majolica background, whilst the platform hall panels are monochromatic. Lighting comes from a set of 12 gilded chandeliers in the central hall with the same blue majolica centre. The remaining decoration of the station include a cream-coloured ceramic tile on the walls, powder coloured marble on the lower pylons and also on the walls, and a chequerboard floor layout of black and gray granite.

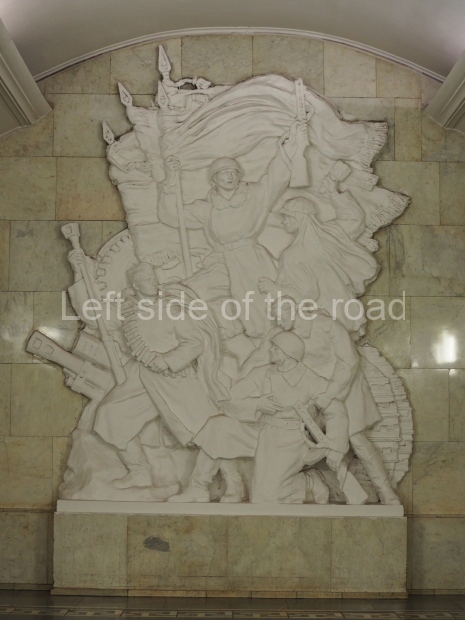

The end of the central hall once had a large sculptural group ‘Stalin and youth’, however this was replaced in 1961 by a new artwork of the same authors (P. Baladin and Ye. Blinova) depicting Vladimir Lenin, Coats of arms of the Soviet Republics and images of Hero-Cities Leningrad, Stalingrad, Sevastopol and Odessa. This was also taken down in late 1966 to make way for a transfer to the newly opened Taganskaya of the Zhdanovskaya line. Further transfer was opened in 1979 by adding a stairwell into the middle of the central hall for the new station Marksistskaya of the Kalininskaya line.

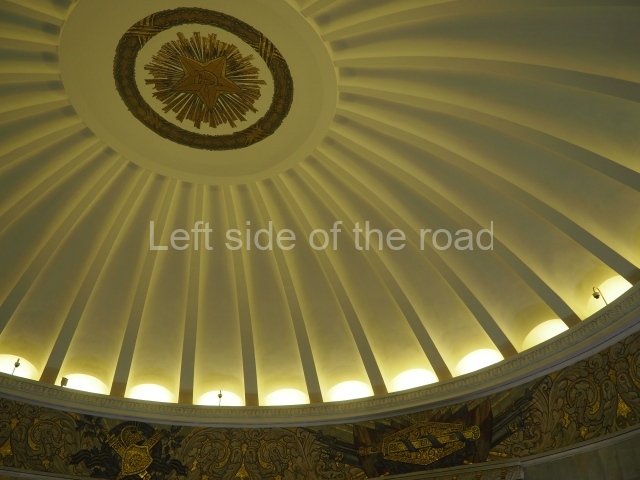

Because the Taganka Square is located on the hill, in order to conveniently place the large vestibule, and also preserve a nearby heritage building, the escalator descent had to be broken, and an intermediate hall was added by placing a large cylinder and gradually lowering to the required depth. After a dome was added, the interior work on the new lobby began, the walls of which are faced with Altai marble, Oroktoy with Syringa shade, and the pilasters from white marble. The dome contains a large ceiling fresco, Victory Fireworks by A. Shiryaeva.

On 18 November 2005 the vestibule was closed for restoration, during which old escalators (installed in 1949) were replaced. All of the decoration features were renovated, and the upgrade included new turnstiles, ticket offices and security upgrade. The station was re-opened on 20 December 2006.

It was the deepest station in Moscow Metro from 1950 until 1958.

Text from Wikipedia.

Location:

Tagansky District, Central Administrative Okrug

GPS:

55.7418°N

37.6517°E

Depth:

53 metres (174ft)

Opened:

1 January 1950